Abstract

Background

Research has shown that cultural competence training improves the attitudes, knowledge, and skills of clinicians related to caring for diverse populations. Social Justice in medicine is the idea that healthcare workers promote fair treatment in healthcare so that disparities are eliminated. Providing students with the opportunity to explore social issues in health is the first step toward decreasing discrimination. This concept is required for institutional accreditation and widely publicized as improving health care delivery in our society.

Methods

A literature review was performed searching for social justice training in medical curricula in North America.

Results

Twenty-six articles were discovered addressing the topic or related to the concept of social justice or cultural humility. The concepts are in accordance with objectives supported by the Future of Medical Education in Canada Report (2010), the Carnegie Foundation Report (2010), and the LCME guidelines.

Discussion

The authors have introduced into the elective curriculum of the John A. Burns School of Medicine a series of activities within a time span of four years to encourage medical students to further their knowledge and skills in social awareness and cultural competence as it relates to their future practice as physicians. At the completion of this adjunct curriculum, participants will earn the Dean's Certificate of Distinction in Social Justice, a novel program at the medical school. It is the hope of these efforts that medical students go beyond cultural competence and become fluent in the critical consciousness that will enable them to understand different health beliefs and practices, engage in meaningful discourse, perform collaborative problem-solving, conduct continuous self-reflection, and, as a result, deliver socially responsible, compassionate care to all members of society.

Background

In our increasingly diverse society, the imperative to understand cultural pluralism becomes undeniable. In the health professions this is especially true, as lack of attention to sociocultural variations in the understandings of health and illness lead to patient dissatisfaction, non-adherence, and poor health outcomes.1 The racial/ethnic disparities in health addressed in the Institute of Medicine report, Unequal Treatment, make it clear that the duty of a physician includes social responsibility and accountability toward the emotional, cultural, and socioeconomic context of the patients he/she seeks to treat. In medical education, cultural competence refers to knowledge, attitudes, and skills that enable health care professionals to communicate with and understand the culturally diverse health beliefs and practices of their patients. Aspects of diversity include, but are not limited to, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and country of origin.1,2 The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) has recently included cultural competency educational objectives (ED-21 and ED-22) necessary for medical school accreditation. These objectives state that medical students must demonstrate an understanding of how culturally diverse perceptions of health and illness affect response to symptoms, disease, and treatment. They also require students to understand how gender and cultural biases affect health care delivery.

To foster active ownership and understanding of this duty to future patients, the authors proposed an elective curriculum that was accepted by the John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM) at the University of Hawaii. Beginning with the class of 2015, JABSOM has launched a four year adjunct elective program leading to its first “Dean's Certificate of Distinction” in Social Justice. The program is dedicated to addressing the necessity to improve health care delivery by future physicians. The certificate encompasses a variety of activities that cultivate humanitarianism and social responsibility throughout medical school with the expectation that students will continue such activities in their practice, and have the skills and desire to care for those most in need. This certificate program challenges its participants not only to internalize required objectives in cultural competency but to translate their understanding of biases and inequalities into tangible strides toward eliminating disparities.

Methods

To identify publications addressing undergraduate medical education requirements in cultural competency as well as the current recommendations for implementing these standards, the authors systematically searched the PubMed database. Search terms were: cultural competency, education; cultural competence, education; social justice, education; social justice, program development. Relevant articles focused on social justice and cultural competency training through medical school curriculum. Only English-language studies were chosen and the search was limited to the past ten years. Studies and reviews were limited to those published regarding United States and Canadian medical education, as that is the scope of the LCME governance. Reviews were also limited to undergraduate medical education and excluded residency or clinician-level training. Search criteria included nursing school programs in social justice and cultural competency training, as a means of comparing similar programs. The authors searched for additional publications in the bibliographies of those that had been already discovered, as well as in literature reviews that included descriptions of important publications on these topics.

Results

Twenty six articles were found addressing social justice curriculum or cultural humility training. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Future of Medical Education in Canada (FMEC) Project are two widely respected authorities on medical education reform. The Carnegie Foundation provided the foundation for progressive medical education reform at the beginning of the 20th century with its Flexner Report, which laid the foundation for current medical education. In 2007, the FMEC Project looked at current and future undergraduate medical education, and like Flexner, created a set of recommendations that summarized new priorities for medical education in light of the new challenges facing medicine in the 21st century.3 In addition to FMEC, the Carnegie Foundation also released a report in 2010, Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency.4 A follow up to the Flexner Report of 1910, this report calls for new innovations in medical education to address the ever-changing climate of medical practice.

FMEC makes it clear that medical education in the areas of cultural competence and social responsibility is required to improve the delivery of care and health outcomes. The mandate of this report dovetails with goals to promote “civic professionalism” in which physicians and medical students feel obligated not only to the individual patient, but also to local and global communities. The American Board of Internal Medicine released a document entitled The Charter on Medical Professionalism in 2002. Among their three fundamental values defining medical professionalism is the principle of social justice, which requires physicians to work actively to “eliminate discrimination in health care” and to “promote fair distribution of health care resources.”5 Further, a 2010 national study from the Center for Studying Health System Change revealed that 48.6% of physicians are not comfortable communicating with patients due to language or cultural barriers.6 Thus, it is imperative to provide students early opportunities to obtain the skills necessary to overcome potential barriers that will otherwise hinder patient care.

A number of articles address cultural competency and medical education. It is clear that future physicians need these skills and it has been shown that cultural competence training is, indeed, effective.7 Research has shown that cultural competence training improves attitudes, knowledge, and skills of clinicians to care for diverse populations. This is most evident in the doctor-patient encounter during which physicians are able to engage in a richer dialogue with the patients and increase both seeking and sharing information during the medical visit.1,10 Previous efforts in cultural competence education have employed the categorical approach in which attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of specific cultural groups are taught. Unfortunately, this approach often leads to oversimplification and stereotyping of a culture, and this loses utility in clinical practice as a patient's cultural context is much more complex than a list of features. The realization of this unintended outcome has resulted in a shift toward teaching a set of skills and a framework that allow a clinician to assess individually what sociocultural factors might affect that patient's care.1 Learning these skills can be especially helpful to physicians in providing care for patients who have different cultural backgrounds, health care experiences, and understandings of the biomedical model. Kumagai and Lypson point out that it is not enough to aim to become culturally competent. It is important to emphasize the idea of “critical consciousness,” which is to develop a reflective awareness of one's own biases, assumptions, and beliefs, and then to push beyond that understanding in order to take action toward creating justice.8 Many authors echo the belief that education must go beyond informative cultural competency training to transform learners to develop the long-term “critical consciousness.”6, 9–12

A 1998 article in the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved offers the term “cultural humility” instead of “cultural competence.” The term humility exchanges the notion of cultural mastery for a “lifelong commitment to self-reflection and self-critique” and acknowledgement of patient-physician imbalances.13 DasGupta, et al, describe how these shifts in thought processes can lead to significant changes in the patient-physician relationship, and ultimately in health outcomes. If one is to develop a “critical consciousness,” it is clear that social justice and cultural humility cannot be taught in a one-hour lecture format. It is a way of thinking that must be integrated throughout the whole of the educational experience and continued as a lifelong skill.14 Suggested strategies from the FMEC include linking social accountability objectives to measurable health care outcomes, providing students with opportunities to learn in low-resource and marginalized communities, and providing greater support to medical students and faculty as they work in community advocacy and develop closer relationships with the communities they serve.15

Hage and Kenny describe a Social Justice Approach to Prevention, which focuses on empowering trainees and engaging them in community conditions through education, research, interventions, and political processes.16 The FMEC provides specific recommendations to increase the integration of prevention and public health into the MD education curriculum. This involves: (1) working in multidisciplinary, inter-professional teams; (2) understanding the role of physicians in health promotion, assessing health policy, and health systems, providing culturally safe care, “thinking upstream prevention” to develop a social justice program; and (3) understanding the social determinants of health, which include education, employment, culture, gender, housing, income and social status, and how these affect patients and communities.3 Suggestions for developing this change include teaching learners how to look at individuals in the context of their environments, consider both patient-doctor and population-doctor relationships, and identify patients who are part of “at-risk” populations, as well as teaching learners to apply critical appraisal of evidence to individual patient care (building on the concept of “critical consciousness” mentioned earlier). The importance of these concepts must be echoed in the objectives of a program in social justice.

The recommendations made by the Carnegie Foundation are grouped into a number of themes. Within the theme of standardization and individualization of the curriculum, this report recommends offering elective programs for students and residents to work in areas of special interest, such as public health/advocacy and global health. They envision learners taking on “multiple professional roles and commitments associated with being a physician,” which include advocacy and interprofessional collaboration to achieve the best health outcomes for their patients. A social justice curriculum would address this recommendation by offering students opportunities to pursue in these areas. In addition, it may serve as a platform for other disciplines, such as public health, law, and/or social work, to offer electives in their area of expertise.

Finally, the University of Massachusetts Medical School has developed a Global Longitudinal Pathway to afford their students domestic and international experiences with poor populations. The longitudinal program is based on the idea that cultural competence is not “acquired at a given period but is a continuous process of self-examination and global perspective taking.”17 These authors also prefer the term cultural humility in order to emphasize continual learning and self-reflection. By integrating opportunities in patient advocacy, cultural humility, and civic engagement throughout their students' four-year undergraduate medical education, participants clearly demonstrate increased confidence in their skills and attitudes toward serving diverse populations. This program is just one example of how to impart lifelong skills in cultural humility while fulfilling LCME guidelines according to FMEC and Carnegie Foundation recommendations.

Discussion

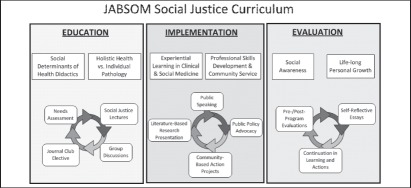

As Hawai‘i's only MD granting institution and the leading provider of doctors for Hawai‘i18 JABSOM is uniquely obligated to address the need for its students to develop skills in cultural humility. To help students in the pursuit of meeting the goals and recommendations described above, JABSOM has launched a pilot four year adjunct elective program leading to the “Dean's Certificate in Social Justice,” the first Dean's Certificate in the JABSOM curriculum. This is the first such program in America or Canada specifically addressing social justice (though other programs may share similar principles). This unique curriculum and opportunity for medical students at JABSOM echoes the national efforts regarding reform in medical education for improving health care delivery. The pilot program consists of a series of activities over a time span of four years to encourage medical students to further their knowledge and skills in cultural competence longitudinally as it relates to their future practice as physicians. An overview of the program is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of Social Justice Curriculum. Phase I: Education and Didactics. Phase II: Implementation and Action. Phase III: Self-Reflection and Personal Growth.

The authors designed the curriculum to link social accountability to health care outcomes by requiring participants to engage in a community and/or scholarly project that addresses social determinants of health. In addition, participants are required to be active members of JABSOM's resident interest group in social justice (Partnership for Social Justice), which will promote greater support for medical students and faculty as they work in community advocacy, interdisciplinary collaboration, and develop closer relationships with the communities they serve. Thirdly, in partnership with the existing medical education curriculum at JABSOM, and activities such as the HOME (Homeless Outreach and Medical Education) project and the Department of Native Hawaiian Health's cultural competency curriculum, the social justice certificate program encourages students to participate in opportunities to learn in low-resource and marginalized communities through the various rural health and community health center options for various clinical requirements throughout the standard JABSOM curriculum.

An important aspect of the curriculum is the integration of classroom education with clinical experience. The concept of gaining knowledge and experience to help gain understanding of the patient's narrative is a key element in this pilot program described by Kumagai and Lypson.7 Through both didactic and experiential learning, the goal is to engage participants in precisely this type of integration. By encouraging students to participate in course work, readings, and lectures that focus on different aspects of social justice in health, while simultaneously encouraging students to be active in local communities through volunteer service, community-based projects, and/or research, students will integrate the concepts of social justice with action and experience.

Furthermore, this program utilizes a particular strength of JABSOM, the problem based learning curriculum. Studies of curricular implementation in this area have shown that facilitated small group discussions are an effective method in eliciting self-reflection on beliefs, values, and experiences.19 This environment provides a mutually supportive atmosphere that encourages students to explore their own biases, and this is the critical first step in appreciating broader cultural differences. Based on this and other research, our program is designed to utilize the benefits of the small-group experience to encourage discussion and self-reflection regarding social issues inherent in health and medicine in both formal and informal classroom and meeting settings.

An essential aspect of this pilot program is assessment and evaluation of its efficacy in achieving the program's goal to produce culturally competent, socially responsible physicians dedicated to serving the underserved. The four-year program requires an entry and exit assessment of its participants to evaluate growth in competence of the curriculum objectives. Administrative support will be required to engage in longitudinal assessment of the participants after graduation from JABSOM as they choose type and geographic location of their careers in medicine. Because of the amount of time it takes to complete undergraduate medical education and residency, the authors estimate it may take more than ten years to establish meaningful data on the efficacy of this program.

This pilot program at JABSOM rests on a strong foundation of understanding social determinants of health. This requires medical students to engage in collaboration with students and faculty of education, law, social work, business, public health, and various community organizations. Using a holistic definition of health to include such things as access to affordable housing, healthy foods, quality education, and fair legal action, the need to collaborate becomes obvious. Importantly, we strive to encourage a self-reflective attitude, the crux of developing a “critical consciousness” that is vital in practicing socially responsible medicine.6 The principles of social justice go beyond acknowledgement and understanding of cultural differences to promote equity and the dignity of each individual. The hope of this program is to foster ideals of humanitarianism and social responsibility throughout the medical education experience so that it may become a life-long enterprise.

This supplement to the existing medical education curriculum at JABSOM is more than a novel addition; it is part of the currently evolving mandate of medical education reform. Providing students with the opportunity to explore social issues in health care is not only part of the current guidelines for institutional accreditation, it is a widely publicized component of improving future doctors and health care delivery in our society. This is true on a national level, and the issues manifest uniquely in the state Hawai‘i. It is the hope and the focus of the authors' efforts to encourage medical students to go beyond cultural competence and become fluent in the critical consciousness that will enable them not just to understand different health beliefs and practices, but engage in meaningful discourse, collaborative problem-solving, and continuous self-reflection that allows for the delivery of socially responsible, compassionate care to all members of society.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Adrian Jacques Ambrose for his collaboration in the creation of the curriculum and the figure used in this paper, Dr. Kelley Withy for her support in creating this curriculum and for her contributions to this paper, and Drs. Gregory Maskarinec, Seiji Yamada, and Keawe Kaholokula for their roles in the creation and implementation of the curriculum and their support of this cause.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Betancourt JR, Green A. Linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(4):583–585. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b2f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim RF, Wegelin J, Hua L, Kramer EJ, Servis ME. Evaluating a lecture on cultural competence in the medical school preclinical curriculum. Academic Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):327–330. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, author. The Future of Medical Education in Canada (FMEC): a collective vision for MD education. 2010

- 4.Irby DM, Cooke M, O'Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(2):220–227. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.“Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter.” Project of the ABIM Foundation, ACP —ASIM Foundation, and European Federation of Internal Medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;136(3):243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reschovsky JD, Boukus ER. Modest and uneven: Physician efforts to reduce racial and ethnic disparities. The Center for Studying Health System Change. 2010:130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach MC, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical Care. 2005;43(4):356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Academic Medicine. 2010;84(6):782–787. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharamsi Shafik. Moving beyond the limits of cultural competency training. Medical Education. 2011;45:764–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dykes DC, White AA. Culturally Comptent Care Pedagogy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1813–1816. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1862-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun MBJ. Pitfalls to avoid when introducing a cultural competency training initiative. Medical Education. 2010;44:613–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betancourt JR. Cultural Competence and Medical Education: Many Names, Many Perspectives, One Goal. Academic Medicine. 2006 Jun;81(6):499–501. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225211.77088.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor and Underserved. 1998;9:117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DasGupta Sayantani, et al. Medical Education for Social Justice: Paulo Freire Revisited. J Med Humanit. 2006;27:245–251. doi: 10.1007/s10912-006-9021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, author. The Future of Medical Education in Canada (FMEC): a collective vision for MD education. 2010

- 16.Hage SM, Kenny ME. Promoting a Social Justice Approach to Prevention: Future Directions for Training, Practice, and Research. J Primary Prevent. 2009;30:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanetti ML, et al. Global Longitudinal Pathway: Has Medical Education Curriculum Influenced Medical Students' Skills and Attitudes Toward Culturally Diverse Populations? Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2011;23(3):223–230. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2011.586913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephans Laura, Withy Kelley, Racsa Phillip. Migration Analysis of Physicians Practicing in Hawaii from 2009–2011. Hawaii Med J Workforce Edition. 2012 Feb; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Branch WT., Jr Small-group teaching emphasizing reflection can positively influence medical students' values. Academic Medicine. 2001;76(12):1171. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]