Abstract

Background

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an infectious bacterium posing serious threats to human health. Due to the difficulty in performing molecular biology experiments to detect protein interactions, reconstruction of a protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis by computational methods will provide crucial information to understand the biological processes in the pathogenic microorganism, as well as provide the framework upon which new therapeutic approaches can be developed.

Results

In this paper, we constructed an integrated M. tuberculosis protein interaction network by machine learning and ortholog-based methods. Firstly, we built a support vector machine (SVM) method to infer the protein interactions of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by gene sequence information. We tested our predictors in Escherichia coli and mapped the genetic codon features underlying its protein interactions to M. tuberculosis. Moreover, the documented interactions of 14 other species were mapped to the interactome of M. tuberculosis by the interolog method. The ensemble protein interactions were validated by various functional relationships, i.e., gene coexpression, evolutionary relationship and functional similarity, extracted from heterogeneous data sources. The accuracy and validation demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of our framework.

Conclusions

A protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis is inferred from genetic codons and interologs. The prediction accuracy and numerically experimental validation demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of our method. Furthermore, our methods can be straightforwardly extended to infer the protein interactions of other bacterial species.

Background

M. tuberculosis which causes tuberculosis affecting lungs and other organs is the second largest cause of death from infectious diseases [1]. An extensive protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of M. tuberculosis can lead to more comprehensive screens of cellular operations. In this context, development of approaches to infer its interactome will contribute to identifying infectious mechanisms, detecting important drug target proteins and promoting potential therapy innovations. To date, genome-wide experimental and computational systems for studying PPIs in M. tuberculosis are unavailable [2]. It is necessary to develop approaches capable of converting available genomic data into functional information of protein-interaction map for M. tuberculosis. E. coli is one of the best model systems to study bacterial physiology [3], with relatively well-characterized interactome, genome and transciptome [4]. It is believed that the protein interactions are conserved in different organisms [5]. The interaction features can be learned by machine learning methods, such as support vector machines (SVMs) [6,7], and also it is common to predict protein interactions from the known interactions of other organisms by interolog method [8].

Compared with other methods, sequence-based prediction methods are superior for their simple requirement on the data, which could be implemented when the species have completely sequenced genomes. There were some studies that are based on sequence information have been successfully performed on PPI prediction of some model organisms such as H. sapiens, S. cerevisiae and E. coli [6,9-12]. However, a limitation of these methods is the requirement of large size of training data to meet a satisfactory accuracy criterion. For model organisms, we have a large volume of prior PPIs that can be used as training data, but there are few experimental data of PPI for some dangerous bacteria like M. tuberculosis. Thus, a novel integration method is necessary to be developed. In this work, we provided cross-species PPI predictions in M. tuberculosis by integrating different types of protein interaction information of other species. Genetic information in the form of codons, i.e. tri-nucleotide sequences, are translated into proteins [13]. It is well known that codon usage is correlated with expression level [9,13]. The codon which carries genetic information specifies the amino acid sequence in the polypeptide during the synthesis of proteins. The genetics of coding sequences is not only the blueprint for translating amino acids, but also the continuous original information for genetic transcription of gene expression. Here, genetic codons will be selected as the sequence features in the learning of interaction patterns. Moreover, the corresponding orthologs of interacting proteins in other organisms will provide more information about the potential interaction mappings by comparative genomics.

In this work, we developed a systematic method combining heterogeneous data sources to infer a comprehensive protein interaction map for M. tuberculosis. The codon features of interacting protein pairs are detected and used to train an SVM classifier. Then the interactome of M. tuberculosis is predicted by the codon-based method. Moreover, the interactions from 14 other species are mapped to M. tuberculosis by the interolog method. The available data from multiple levels including gene coexpression, evolutionary relationship and functional similarity are implemented to assess these predicted interactions by confidence significance. The evidence from various sources validates the effectiveness of our method. The network properties of the constructed protein-interaction map are also identified. The predicted protein interaction network as well as the proposed method provide a framework for the functional specificities study of M. tuberculosis.

Results

Predictor performance

E. coli is one of the best characterized organisms [3,4] and we chose it as a model system for building the protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis. The positive and negative sets of protein interactions in E. coli were designed to test the performance of our codon-based prediction methods. The genome and proteome of E. coli were downloaded and prepared for the interacting sets as well as all known opening reading frames (ORFs) [14]. The distance of two ORFs in terms of usage of codon c is defined as

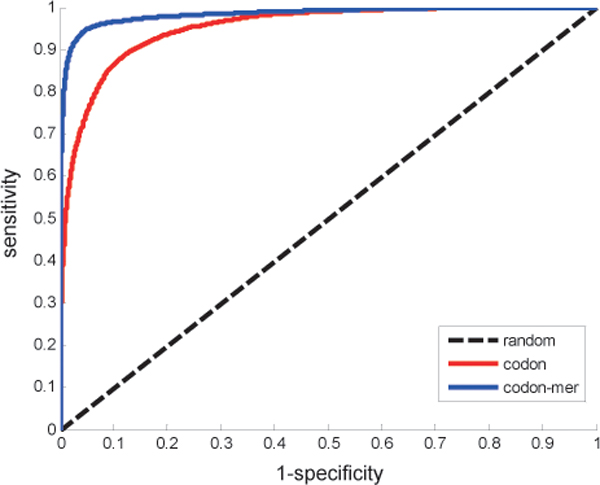

where fi(c) and fj(c) are relative frequencies of codon c in ORF i and ORF j. By codon definition, ∑k fi(ck) = 1 and ∑k fj(ck) = 1 for k = 1, 2,..., 64 in all codons. There are 14058 pairs of interactions and 27882 pairs of non-interactions in 4227 proteins of E. coli. A five-fold cross validation process is implemented in these pairs, i.e., we train the SVM classifier based on the related codons in the 80% interacting pairs forming the training part and test the prediction in the rest part. Figure 1 shows the performance of prediction results of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves by the SVM predictor using genetic codon features. As we know, there are several codons corresponding to the same amino acid in genetic code. The prediction performance of merging the frequency of these degenerate codons ('codon-mer') is also shown in Figure 1. The details of prediction precision and accuracy are listed in Table 1. The SVM predictor can achieve the prediction accuracy (ACC) of 0.9003 and the area under curve (AUC) of 0.9507 in the PPI of E. coli. These results provide pieces of evidence for the effectiveness and efficiency of predicting protein interactions from the genetic codons by machine learning method.

Figure 1.

ROC curves of the five-fold cross validation predictions in E. coli.

Table 1.

Prediction performances of the codon-based SVM predictor in E. coli

| Feature | ACC | SN | SP | PRE | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codon | 0.9003 | 0.7576 | 0.9486 | 0.8327 | 0.9507 |

| Codon-mer | 0.9595 | 0.8986 | 0.9801 | 0.9386 | 0.9835 |

Protein interactions in M. tuberculosis

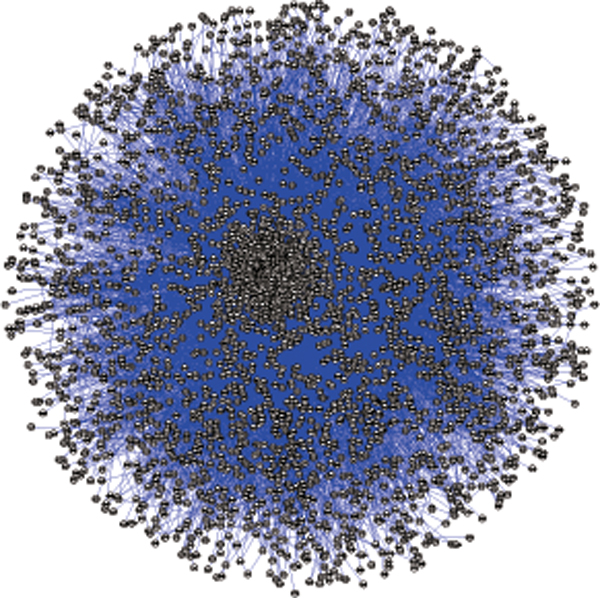

To explore protein interactions in M. tuberculosis, we used the formerly trained SVM classifier to infer the interactions of M. tuberculosis by the codon message of ORFs in gene sequence level. Based on the genetic codons of the laboratory strain H37Rv of M. tuberculosis, we predicted 12,899 interactions in 3,266 proteins. Furthermore, the known protein interactions of other species were mapped to the proteome of M. tuberculosis by interolog method. We collected the documented interactions of 14 species from PPI databases, IntAct and DIP, and the sequence features of interacting proteins were transferred into the M. tuberculosis proteome by ortholog detection. Table 2 lists the detailed prediction results by interolog method. So far, we also found 530 pairs of protein interactions of M. tuberculosis from various databases, such as BIND [15] and Reactome [16]. Combining with these known interactions, we built a comprehensive protein interaction map totally with 46,119 interactions of 3,465 proteins in M. tuberculosis. The inferred protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Details of predicted protein interactions in M. tuberculosis

| Species | Database | Original PPI | Predicted PPI | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By machine learning | ||||

| E. coli | ECID | 14,058(positive)+ 27,882(negative) |

12,899 | 27.97 |

| By interolog | ||||

| Escherichia coli | IntAct | 14,158 | 16,468 | 35.71 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | IntAct | 11,870 | 7,674 | 16.64 |

| Treponema pallidum | IntAct | 3,744 | 324 | 0.70 |

| Synechocystis | IntAct | 2,625 | 2,481 | 5.38 |

| Myxococcus xanthus | IntAct | 384 | 253 | 0.55 |

| Synechocystis sp. | IntAct | 219 | 220 | 0.48 |

| Rickettsia sibirica | IntAct | 282 | 24 | 0.05 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | IntAct | 193 | 47 | 0.10 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | DIP | 22,650 | 1,558 | 3.38 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | DIP | 21,769 | 2,701 | 5.86 |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | DIP | 3,979 | 229 | 0.50 |

| Homo sapiens | DIP | 1,485 | 84 | 0.18 |

| Mus musculus | DIP | 287 | 36 | 0.06 |

| Rattus norvegicus | DIP | 69 | 2 | 0.15 |

| Total: 46,119 interactions in 3,465 proteins (with 530 known PPIs) | ||||

Figure 2.

Inferred protein interaction map in M. tuberculosis.

Validation results

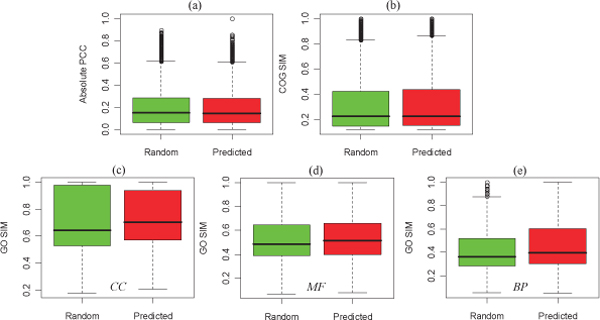

Interacting protein pairs have been identified with close relationship of gene coexpression [17], coevolution [18], similar GO annotations [19], phenotype association and similar physicochemical elements [20]. For M. tuberculosis species, we got these available heterogeneous data sources to annotate every predicted interacting pairs.

Firstly, we annotated the predicted interacting protein pairs by their corresponding Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC) of gene coexpression. For comparison, we calculated the corresponding correlation values of these same-size random selected protein pairs. Every prediction was then annotated by a coexpression value in gene expression profiling. Figure 3(a) shows the boxplot of coexpression values in the predictions. From Figure 3(a), we identified that the coexpression values in the predicted interacting pairs tend to be more correlated when compared to the same-size randomly selected pairs (P-value = 4.69 × 10-3, Mann-Whitney U test). Secondly, we identified the evolutionary relationship of the interacting proteins by the clusters of orthologous group (COG) information. The interacting proteins were detected in their own COG individually. Figure 3(b) shows the boxplot of evolutionary relationship values in the predicted interacting pairs and that of the same-size randomly selected protein pairs. Their difference measured by the Mann-Whitney U test (P-value = 0.53) is not significant, while every predicted interaction gets a confidence value of evolutionary relationship. Thirdly, we calculated the functional similarities underlying these predicted interactions. We detected the semantic similarity between the gene ontology (GO) term pairs of interacting proteins. We have considered the hierarchical structure of GO directed acyclic graph and the specificity of GO terms in the identification. We identified the functional relationships between predicted interacting proteins by three ontology categories, i.e. cellular component ('CC'), molecular function ('MF') and biological process ('BP'), respectively. The boxplots of the three values of GO similarities in the random pairwise proteins and that in predicted pairs are shown in Figure 3(c), (d) and 3(e), respectively. The predicted interactions have higher values of functional similarity than random ones (P-values are 6.63 ×10-4, < 2.2 ×10-16 and < 2.2 ×10-16, respectively), which further provides evidence for the effectiveness of our methods. After annotating from various information, we provide the evaluation confidence to every predicted interactions.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of coexpression (a), coevoluation (b) and cofunction values (c)-(e) of the predicted interactions and that of the same-size random selected protein pairs.

Network analysis

For global views of the protein-interaction map, we identified the topological features of the integrated protein interaction map and the features of particular interactions. Firstly, we detected the original features in the primary constructed network by machine learning and interologs combined with the known interacting protein pairs. The measures of degree distributions, clustering coefficients, characteristic shortest path and network diameter are identified individually. Table 3 lists some network properties. Network diameter is the longest path between any two proteins. The characteristic path length is calculated by averaging minimum distance between protein pairs. Clustering coefficient is a measure of degree to which nodes in a network tend to cluster together [21]. A network whose degree distribution follows a power law is often called a scale-free network [22]. These measures refer to the details of the properties of the inferred protein-interaction map of M. tuberculosis. The hub proteins as well as interested proteins can be selected to analyze for particular dysfunctions of M. tuberculosis. From the validations of gene coexpression, evolutionary relationship in COGs and functional similarity, we can check and filter out those pairs consistently included in various level information by evaluating the reliability of interactions. We then calculated the features in the filtered network by omitting the pairs with lower confidence values, while we kept the predictions when there are no available evaluations for them. We also identified the distribution of node degree and found that the constructed protein interaction network satisfied the topology features of complex networks [22]. The processes are based on the network analysis of fitting the distribution of a scale-free network, and the parameter γ value is asymptotically in the range 1 <γ < 2 in the power-law distribution fitting. There are 477 hub proteins in the protein interaction map when the degree threshold is 50. The hub proteins from different thresholds can be found in Additional file 1.

Table 3.

Topological parameters of protein-interaction map in M. tuberculosis

| Threshold | Node | Edge | Diameter | Characteristic path length | Clustering coefficient | Power law fitting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 3465 | 46119 | 8 | 3.341 | 0.093 | 1.237 |

| 0.5 (PCC) | 3409 | 35582 | 8 | 3.419 | 0.074 | 1.310 |

| 0.5 (COG) | 3397 | 43425 | 8 | 3.445 | 0.099 | 1.220 |

| 0.5 (GOCC) | 3461 | 45193 | 8 | 3.355 | 0.091 | 1.245 |

| 0.5 (GOMF) | 3400 | 31045 | 8 | 3.632 | 0.067 | 1.431 |

| 0.5 (GOBP) | 3373 | 26200 | 9 | 3.713 | 0.076 | 1.440 |

| 0.5 + 0.5 + 0.3 | 3383 | 26827 | 9 | 3.730 | 0.062 | 1.522 |

| (GOCC + GOMF + GOBP) | ||||||

| 0.5 + 0.7 | 3324 | 33134 | 9 | 3.616 | 0.080 | 1.289 |

| (PCC + COG) | ||||||

| 0.5 + 0.9 + 0.8 | 3304 | 29891 | 9 | 3.691 | 0.072 | 1.336 |

| (PCC + COG + GOCC) | ||||||

| 0.5 + 0.7 + 0.4 | 3212 | 13244 | 9 | 4.388 | 0.044 | 1.803 |

| (PCC + GOMF + GOBP) | ||||||

| 0.5 + 0.7 | 3281 | 21240 | 11 | 3.920 | 0.081 | 1.414 |

| (COG + GOBP) |

Discussions

In this work, we proposed a method to build the protein-interaction map in M. tuberculosis by machine learning and interologs. We obtained the interaction features of genetic codon underlying interacting proteins in relatively well-established interactome of E. coli. The features of genetic codons of interacting proteins of E. coli were mapped to the proteome of M. tuberculosis by training an SVM classifier. The cross validation showed the effectiveness and efficiency of our predictor. We also implemented the interolog method to map the documented protein interactions of other organisms into M. tuberculosis. Moreover, the available functional genomic information about M. tuberculosis has been used to evaluate the predicted interactions. These heterogeneous data were combined in a novel framework to infer the interactions in M. tuberculosis. The predicted pairs were checked and can be filtered with these information for potential applications. The constructed protein interaction network of M. tuberculosis provides more information for the infectious bacterium threatening human health.

We used multiple sources of available functional genomic data to provide evaluation of these predicted interactions. Gene coexpression, evolutionary relationship and functional similarity are implemented to check the reliability in the targeted pairs. The information could be directly used to build the functional relationship of protein pairs [23-25]. Due to the limited knowledge in M. tuberculosis, we integrated the heterogeneous information in an alternative framework for assessing the predictions rather than predicting the interactions. Filtering interactions by different confidence values result in different networks of different size and reliability. This will provide valuable resources for biological information in tuberculosis research, which implies the promising applications based on our constructed protein interaction map, which are our future research topics.

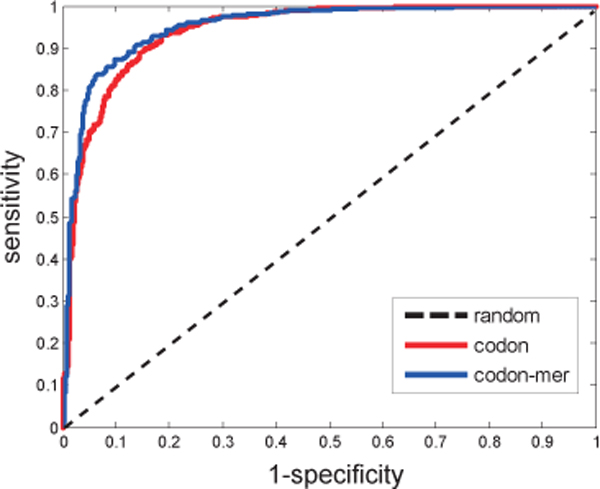

In our framework, we proposed a cross-species prediction by mapping the documented interactions of other species into M. tuberculosis. For completeness, we collected some known curated interactions. We also tested the predictions in these known interactions in M. tuberculosis by training the codon features to check our predictions. Figure 4 shows the ROC curves of prediction performance. Our method can achieve high AUC of 0.945 by the codon-based method and of 0.951 by merging the frequency of these degenerate codons in these known protein interactions. Table 4 shows the results of prediction performances. We achieved similar accuracy by merging the codons as that by the codon-based method. In our previous work, we concluded that there is subtle difference between the two encoding schemes for predicting protein interactions [7]. Both methods are rational and their differences are underlying the data sets. The results provide more evidence for the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed methods.

Figure 4.

ROC curves of predicting performance in the known interactions in M. tuberculosis.

Table 4.

Prediction performances of the SVM predictor in these known protein interactions of M. tuberculosis

| Feature | ACC | SN | SP | PRE | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codon | 0.8728 | 0.8932 | 0.8524 | 0.8582 | 0.9454 |

| Codon-mer | 0.8738 | 0.8971 | 0.8505 | 0.8571 | 0.9507 |

Basically, we implemented two pipelines of building the protein-interaction map of M. tuberculosis, i.e., the SVM-based machine learning method and the interolog mapping method. The two methods are essentially close-related. The gene sequence information of interacting pair of proteins has been learned by the predictor and that of these known interactions is mapped to the protein pairs of M. tuberculosis. In the same manner, the interolog method identifies the interaction between a pair of proteins which have interacting homologs in another organism. The protein sequence information of known interaction is mapped by the cross-species sequence similarity detection. It is an interesting research topic to identify the quantitative relationship between the prediction results of the two methods. The various mapping schemes of the sequence information have been integrated in our predictions. The gene sequence information as well as the protein sequence information is exploited to infer the protein-interaction map of M. tuberculosis. The other research direction is to implement other schemes to encode the sequence information in the machine learning method, such as the autocorrelation encoding scheme [26] and triplet residues method [6]. We combined the gene sequence information and the protein sequence information into an integrated framework. It is also an interesting topic to investigate the prediction difference of the two-level sequence information.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we provided a novel framework to integrate genomic data to infer a protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis. We predicted the protein interactions in M. tuberculosis by an SVM based classifier by genetic codons. And the documented protein interactions from various species were also mapped to the proteome of M. tuberculosis by interolog method. The information from gene expression, evolutionary and functional relationship provided reliability measures of evaluating our predictions. The validations provided clear evidence for the effectiveness of our method. Our framework can easily be extended to infer the large-scale protein interaction map in other species. These predicted interactions provide a valuable reference of interactome for M. tuberculosis research. The PPIs build a frame to further study the functional implications underlying the interactome of M. tuberculosis. They are listed in Additional file 2. The details are available at: http://www.aporc.org/doc/wiki/MTBPPI.

Methods

Framework of prediction

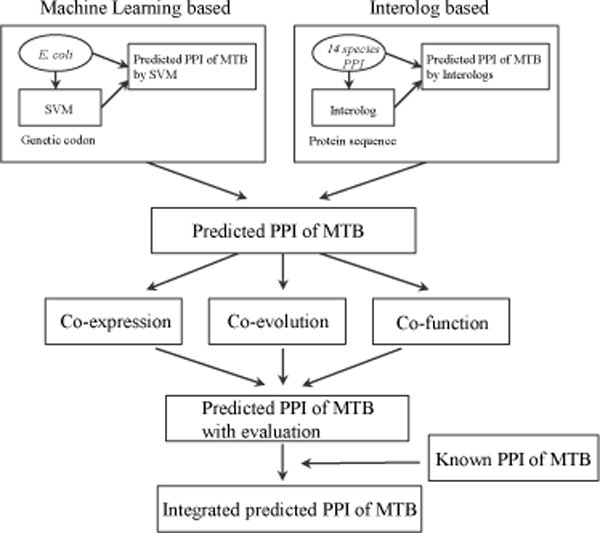

Figure 5 shows our framework to infer the protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis. The protein interactions were predicted by two main pipelines. Firstly, we built the protein interaction network of M. tuberculosis from codon features of interacting proteins in E. coli by a machine learning approach. The integrated interaction map and gene sequences of E. coli were downloaded from EcID, which collects comprehensive PPIs in E. coli by combining various knowledge [4]. We used the information of protein interactions of E. coli to train an SVM classifier to get the genetic codon features underlying these interacting pairs. The interactions in M. tuberculosis were then predicted by the trained SVM predictor with the genetic codons of ORFs in gene sequences of M. tuberculosis. We chose the laboratory strain of H37Rv as our model organism [14]. The processes are shown in the upper-left square frame of Figure 5. Secondly, we inferred the protein interactions of M. tuberculosis by interolog method from the documented protein interactions in 14 other species. We collected these interactions from IntAct [27] and DIP [28]. The interacting proteins of each species were detected their homologous proteins of M. tuberculosis by BLAST [29] individually. The homologs of two interacting proteins will be identified as the predicted interactors. The pipeline is shown in the upper-right square framework of Figure 5. As for the validation of predicted results, we tested our method in E. coli and in the known interactions of M. tuberculosis. Three pieces of available information of M. tuberculosis, i.e., gene expression profiling, evolutionary relationship from ortholog database and functional similarity, were used to evaluate the confidence of prediction results. The known protein interactions were of course included in our constructed interactome of M. tuberculosis. Finally, we inferred an integrated protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis.

Figure 5.

Framework of inferring protein interaction map in M. tuberculosis.

SVM-based predictor

We used the SVM method [30] as the classifier. The software libsvm 2.84 [31] was employed and a radial basis function was chosen as the kernel function in our implementation. The positive pairs of training are those known interactions which are experimentally validated in EcID. There were 14,058 pairs of positive interactions. We selected the negative set by choosing the pairs when the length of shortest path between the two terminals in EcID network is larger than a given cutoff of 6 for the small-world property of a complex network [21]. There is few possibility for two proteins to interact with each other when the distance is bigger than the threshold. There were 27,882 pairs of proteins which are included in the negative set. A five-fold cross validation process was implemented to test the accuracy of our SVM-based classifier. We applied the trained predictor to infer the protein interactions in M. tuberculosis.

The prediction performance was evaluated by various parameters, such as sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), accuracy (ACC) and precision (PRE). The evaluation is usually displayed in a ROC graph with measure of area under curve (AUC). Mathematically, these measures are defined as

where TP, TN, FP and FN refer to number of true positive, number of true negative, number of false positive, and number of false negative predictions, respectively.

Validation from multiple resources

We constructed the protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis by genetic codons and ortholog mapping. We also deposited known interactions in databases from experimental results about M. tuberculosis in literatures. Integrated with these known protein interactions, we built a comprehensive PPI map of M. tuberculosis. We collected multiple available resources to access the constructed protein interaction map in M. tuberculosis. The confidence of interactions was evaluated by three extra data sources, namely, gene expression, evolutionary relationship and functional similarity.

Firstly, we identified the PCCs of gene coexpression of pairwise proteins in the predicted network. We downloaded the gene expression profiling data of M. tuberculosis H37Rv from NCBI GEO (ID: GSE9776) [32]. Correlation between genes is calculated by

where and are the means of gene expression profile xi and xj, σi and σj are the standard deviations of them. Secondly, we presented the evaluation of evolutionary relationship between the predicted interacting proteins. COGs were delineated by comparing protein sequences encoded in complete genomes, representing major phylogenetic lineages [33]. Figure 6 presents the method to identify the evolutionary information between the predicted interacting proteins. Each COG consists of individual proteins or groups paralogs from at least 3 lineages and thus corresponds to an ancient conserved domain [33]. The maximum of COG value between two groups in which the interacting proteins are located were regarded as the value representing their evolutionary relationship. Thirdly, GO [34] similarity between the predicted pairs was identified to evaluate their functional relationship. We downloaded the annotations for M. tuberculosis H37Rv from GOA [35]. In GO hierarchical acyclic graph, the terms far from the root would be more informative than those close to the root. We calculated the GO probability for specific GO terms [36]. The frequency of a GO term in a database is defined as

Figure 6.

Identification of evolutionary relationship between two interacting proteins. The maximum of COG value between two groups in which the interacting proteins are located are used as the value of their evolutionary relationship.

where anno(c) is the number of proteins annotated with this terms in our database. The set of child nodes of term c is the children(c). The probability of a term t is then defined as p(c) = freq(c)/freq(root), where freq(root) is the frequency of the root term [37,38]. We used semantic similarity measures [36-38] to evaluate the similarity of GO term lists corresponding to the interacting proteins. Based on these validations, we can check those interactions consistently validated in various information and detect an ensemble protein network by omitting low reliability pairs.

Abbreviations

PPI: protein-protein interaction; SVM: support vector machine; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; AUC: area under curve; ACC: accuracy; SP: specificity; SN: sensitivity; PRE: precision; TP: true positive; TN: true negative; FP: false positive; FN: false negative; BIND: biomolecular interaction network database; BioGrid: biological general repository for interaction datasets; IntAct: molecular interaction database; ORF: opening reading frame; COG: cluster of orthologous group; GO: gene ontology; CC: cellular component; MF: molecular function; BP: biological process; NCBI: national center for biotechnology information; GEO: gene expression omnibus.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ZPL, JW and LC conceived the research. ZPL and JW designed and performed the study. YQQ, RKKL, XSZ and SKWT gave valuable suggestions and improvements. LC supervised the project. ZPL wrote the paper with contributions from others. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Hub proteins in the protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis.

The protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis.

Contributor Information

Zhi-Ping Liu, Email: zpliu@sibs.ac.cn.

Jiguang Wang, Email: wangjg@big.ac.cn.

Yu-Qing Qiu, Email: yqqiu@amss.ac.cn.

Ross KK Leung, Email: ross@cuhk.edu.hk.

Xiang-Sun Zhang, Email: zxs@amt.ac.cn.

Stephen KW Tsui, Email: kwtsui@cuhk.edu.hk.

Luonan Chen, Email: lnchen@sibs.ac.cn.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Shanghai Natural Science Foundation under Grants No. 11ZR1443100 and by the Chief Scientist Program of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences (SIBS), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) under Grant No. 2009CSP002, and by the Knowledge Innovation Program of SIBS of CAS with Grant No. 2011KIP203 and No. KSCX2-EW-R-01. The first author gratefully acknowledges the support of SA-SIBS Scholarship Program. Part of the authors were also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant No. 31100949, 61072149 and 91029301, and partially supported by Aihara Project, the FIRST program from JSPS, initiated by CSTP.

This article has been published as part of BMC Bioinformatics Volume 13 Supplement 7, 2012: Advanced intelligent computing theories and their applications in bioinformatics. Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Intelligent Computing (ICIC 2011). The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcbioinformatics/supplements/13/S7.

References

- Reddy T, Riley R, Wymore F, Montgomery P, DeCaprio D, Engels R, Gellesch M, Hubble J, Jen D, Jin H. et al. TB database: an integrated platform for tuberculosis research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D499–D508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Mai D, Kumar A, Steyn A. Dissecting virulence pathways of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through protein-protein association. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11346–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602817103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arifuzzaman M, Maeda M, Itoh A, Nishikata K, Takita C, Saito R, Ara T, Nakahigashi K, Huang H, Hirai A. et al. Large-scale identification of protein-protein interaction of Escherichia coli K-12. Genome Res. 2006;16:686–691. doi: 10.1101/gr.4527806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres Leon E, Ezkurdia I, García B, Valencia A, Juan D. EcID. A database for the inference of functional interactions in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D629–D635. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh E, Sharan R. Identification of conserved protein complexes based on a model of protein network evolution. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:e170–e176. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Zhang J, Luo X, Zhu W, Yu K, Chen K, Li Y, Jiang H. Predicting protein-protein interactions based only on sequences information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4337–4341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607879104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang J, Yang Z, Deng N. Sequence-based protein-protein interaction prediction via support vector machine. J Syst Sci & Complexity. 2010;23:1012–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Luscombe N, Lu H, Zhu X, Xia Y, Han J, Bertin N, Chung S, Vidal M, Gerstein M. Annotation transfer between genomes: protein-protein interologs and protein-DNA regulogs. Genome Res. 2004;14:1107–1118. doi: 10.1101/gr.1774904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafabadi H, Salavati R. Sequence-based prediction of protein-protein interactions by means of codon usage. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Zhao X, Huang D. Predicting protein-protein interactions from protein sequences using meta predictor. Amino Acids. 2010;39:1595–1599. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0588-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Z, Lei Y, Huang D, Zhou X. Using manifold embedding for assessing and predicting protein interactions from high-throughput experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2744–2751. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Xia J, Li X, Huang D. Predicting protein-protein interactions from sequence using correlation coefficient and high-quality interaction dataset. Amino Acids. 2010;38:891–899. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0295-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Bussemaker H, Gerstein M. Revisiting the codon adaptation index from a whole-genome perspective: analyzing the relationship between gene expression and codon occurrence in yeast using a variety of models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2242–2251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarano C, Andrade C, Anthony K, Bahroos N, Bajec M, Bantoft K, Betel D, Bobechko B, Boutilier K, Burgess E. et al. The Biomolecular Interaction Network Database and related tools - 2005 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D418–D424. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastrik I, D'Eustachio P, Schmidt E, Joshi-Tope G, Gopinath G, Croft D, de Bono B, Gillespie M, Jassal B, Lewis S, Matthews L, Wu G, Birney E, Stein L. Reactome: a knowledge base of biologic pathways and processes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-3-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Greenbaum D, Gerstein M. Relating whole-genome expression data with protein-protein interactions. Genome Res. 2002;12:37–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.205602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jothi R, Kann M, Przytycka T. Predicting protein-protein interaction by searching evolutionary tree automorphism space. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:i241–i250. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi M, Lin Y. False positive reduction in protein-protein interaction predictions using gene ontology annotations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:262. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wu L, Wang Y, Zhang X. Inferring protein interactions from experimental data by association probabilistic method. Proteins. 2006;62:833–837. doi: 10.1002/prot.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert R, Barabasi A. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Reviews of Modern Physics. 2002;74:47. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi A, Oltvai Z. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Marcotte E, Xenarios I, Yeates T. Protein function in the post-genomic era. Nature. 2000;405:823–826. doi: 10.1038/35015694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Yu H, Greenbaum D, Kluger Y, Krogan N, Chung S, Emili A, Snyder M, Greenblatt J, Gerstein M. A Bayesian networks approach for predicting protein-protein interactions from genomic data. Science. 2003;302:449–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1087361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Date S, Adai A, Marcotte E. A probabilistic functional network of yeast genes. Science. 2004;306:1555–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1099511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Yu L, Wen Z, Li M. Using support vector machine combined with auto covariance to predict protein-protein interactions from protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3025–3030. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrien S, Alam-Faruque Y, Aranda B. et al. IntAct-open source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D561–D565. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xenarios I, Salwinski L, Duan X, Higney P, Kim S, Eisenberg D. DIP, the Database of Interacting Proteins: a research tool for studying cellular networks of protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:303–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S, Madden T, Schaffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Lin C. LIBSVM: a library for support vector machines. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 2011;2:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Troup D, Wilhite S, Ledoux P, Rudnev D, Evangelista C, Kim I, Soboleva A, Tomashevsky M, Edgar R. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles-database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D760–D765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov R, Galperin M, Natale D, Koonin E. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camon E, Magrane M, Barrell D, Lee V, Dimmer E, Maslen J, Binns D, Harte N, Lopez R, Apweiler R. The Gene Ontology Annotation (GOA) Database: sharing knowledge in Uniprot with Gene Ontology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D262–D266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord P, Stevens R, Brass A, Goble C. Investigating semantic similarity measures across the Gene Ontology: the relationship between sequence and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1275–1283. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker A, Domingues F, Rahnenfuhrer J, Lengauer T. A new measure for functional similarity of gene products based on Gene Ontology. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZP, Wu LY, Wang Y, Chen L, Zhang XS. Predicting gene ontology functions from protein's regional surface structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:475. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Hub proteins in the protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis.

The protein interaction map of M. tuberculosis.