Abstract

Tumor formation involves the accumulation of a series of genetic alterations that are required for malignant growth. In most malignancies, genetic changes can be observed at the chromosomal level as losses or gains of whole or large portions of chromosomes. Here we provide evidence that tumor DNA may be horizontally transferred by the uptake of apoptotic bodies. Phagocytosis of apoptotic bodies derived from H-rasV12- and human c-myc-transfected rat fibroblasts resulted in loss of contact inhibition in vitro and a tumorigenic phenotype in vivo. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis revealed the presence of rat chromosomes or of rat and mouse fusion chromosomes in the nuclei of the recipient murine cells. The transferred DNA was propagated, provided that the transferred DNA conferred a selective advantage to the cell and that the phagocytotic host cell was p53-negative. These results suggest that lateral transfer of DNA between eukaryotic cells may result in aneuploidy and the accumulation of genetic changes that are necessary for tumor formation.

Apoptosis was initially described by its morphological characteristics, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, chromatin condensation, and nuclear fragmentation (1, 2). In vivo, it is an inconspicuous process because of its rapid clearance by phagocytes or neighboring cells (3), which may explain why small changes in the incidence of apoptosis may have a dramatic effect on the rate of tissue growth or regression (4–6). Cell death by apoptosis may also serve as an anticancer mechanism by restricting the expansion of cells with unleashed proliferative potential. This is exemplified by the finding that expression of the c-myc or E1A oncogenes may promote p53-dependent apoptosis (7–8). There are, however, several pathways by which tumors cells avoid programmed cell death, such as inactivation of the p53 gene or up-regulation of genes, such as bcl-2, which promote survival (9). Tumor apoptosis may also be controlled by factors present in the microenvironment of the tumor, including paracrine survival factors such as insulin-like growth factor 2, or by the recruitment of new blood vessels (6, 10)

Horizontal transfer of genes has been reported in bacteria and fungi and plays an important role in the generation of resistance to antibiotic drugs as well as adaptation to new environments (11–12). In previous studies, we showed that DNA could be transferred from apoptotic cells to recipient cells after phagocytosis. Cocultivation of cell lines containing integrated copies of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) resulted in rapid uptake and transfer of EBV-DNA as well as genomic DNA to the nucleus of the phagocytosing cell (13). This is an efficient mode of gene transfer, because fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of bovine aortic endothelial cells showed uptake of apoptotic DNA in the nuclei of 15% of the phagocytosing cells. Once transferred, expression of EBV-encoded genes was detected at protein and mRNA levels. We have also shown that HIV-DNA is transferred in a similar fashion to cells that are resistant to virus infection, indicating a novel pathway of receptor-independent transfer of HIV (14). The transfer of drug resistance genes has also been proposed to occur via uptake of apoptotic bodies (15).

Here, we investigated the effect of horizontal DNA transfer on cell transformation and tumor progression. We demonstrated that apoptotic bodies derived from tumor cells induce focus formation of p53-deficient fibroblasts in vitro and tumor formation in vivo. We further demonstrate that whole chromosomes or fragments thereof are transferred by this pathway. These studies indicate that horizontal gene transfer between cells may be of importance during tumor progression.

Methods

Cell Culture.

Rat embryonic fibroblasts (REF), mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), and MEF p53−/− (16) were isolated as described (17) and grown in DMEM (HyClone) with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin. REFrm cells are REF cells transfected with H-rasV12, human c-myc (kindly provided by R. N. Eisenman) and a hygromycin resistance gene fused with green fluorescence protein (GFP) (pEGFP-hyg; CLONTECH). For coculture experiments, 2 × 106 MEF or MEF p53−/− cells were trypsinized and transferred to 10-cm Petri dishes. Apoptosis was induced in 10 × 106 REFrm and REF nontransfected cells by irradiation (150 Gy) or by nutrient depletion for 24 h. Irradiated or nutrient-depleted cells were incubated with MEF or MEF p53−/− cells at a ratio of 5:1 for the time points indicated in the figure legends. The tissue culture media were changed after 48 h and then every 3 days. Focus formation was recorded by microscopy after 8 days in culture, as previously described (18).

Apoptosis Detection.

DNA fragmentation was analyzed as described (13). The morphology of apoptotic nuclei was detected by Hoechst 33258 (Sigma) staining.

PCR Analysis and Immunoblotting.

DNA was isolated by using the Qiaamp Blood Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and PCR analysis was performed with specific primers for H-rasV12 (5′-ggcaggagaccctgtaggag-3′, 3′-gtattcgtccacaaaatggttct-5′), human c-myc (5′-gaggctattctgcccatttg-3′, 3′-cagcagctcgaatttcttcc-5′), and hygr (5′-acgtaaacggccacaagttc-3, 3′-aagtcgtgctgcttcatgtg-5). Conditions for PCR amplification were as follows: H-rasV12: 30 sec, 95°C; 45 sec, 61°C; 2 min, 72°C; 30 cycles; human c-myc and hygr: 30 sec, 95°C; 45 sec, 58°C; 2 min, 72°C for 30 cycles. For immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis, 3 × 107 cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/150 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet P-40/1% DOC/0.1% SDS/0.5% aprotinin) at +4°C for 10 min. After sonication (Soniprep 150, Labassco) for 30 s at 50 W, cells were centrifuged for 15 min, 3,000 rpm, at +4°C. The supernatant was incubated with antibody for 1 h at +4°C [H-rasV12 R02120, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY; c-myc (N-262) sc-764, Santa Cruz Biotechnology], and 35 μl ImmunoPure Immobilized Protein G (20398, Pierce) was added to each sample and incubated overnight at +4°C. The precipitates were centrifuged for 5 min, 2,500 rpm, and washed three times in lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis as previously described (19). Filters were blocked with 5% milk (Bio-Rad nonfat dry milk, 170-6404) for 1 h at room temperature, and the membrane was incubated with the primary antibody [pan-H-RasV12 Val-12, OP38, Oncogene Research Products; c-Myc (9E10), Santa Cruz Biotechnology] overnight at 4°C. After washing with 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS, the membrane was incubated with an anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (NA 931, Amersham Pharmacia, Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL) for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane was developed by using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system according to the protocol of the manufacturer (RPN2209, Amersham Pharmacia Pharmacia Biotech.).

Tumorigenicity Assays.

Severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment. Approximately 4 × 106 MEF p53−/− cells cultivated with either apoptotic REF or REFrm cells were injected into the dorsal s.c. space of 6- to 7-week old SCID mice. Injections of MEF p53−/− cells and REFrm cells served as negative and positive controls.

FISH and GFP Analysis.

Interphase nuclei and metaphase chromosomes were analyzed on standard cytogenetic preparations, as previously described (20). The rat genomic DNA was labeled by nick translation with biotinylated-16-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim) by using the BIONICK labeling kit (GIBCO/BRL). The human c-myc DNA probe was labeled with Spectrum Orange (Vysis). Hybridization was performed in 50% formamide, 2 × SSC, and 10% dextran sulfate at 37°C overnight, as described (20). Biotin signals were detected with FITC-avidin DCS (Vector Laboratories) and amplified with one layer of biotinylated antiavidin antibody (Vector Laboratories), followed by one layer of FITC-avidin (21). Chromosomes and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The slides were examined with a Leica DMRBE microscope equipped with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu 4800, Middlesex, NJ) and filter sets specific for the fluorochromes (DAPI, FITC, and Spectrum Orange). GFP staining was visualized as previously described (22).

Results

Tumor Apoptotic Bodies Induce Foci Formation.

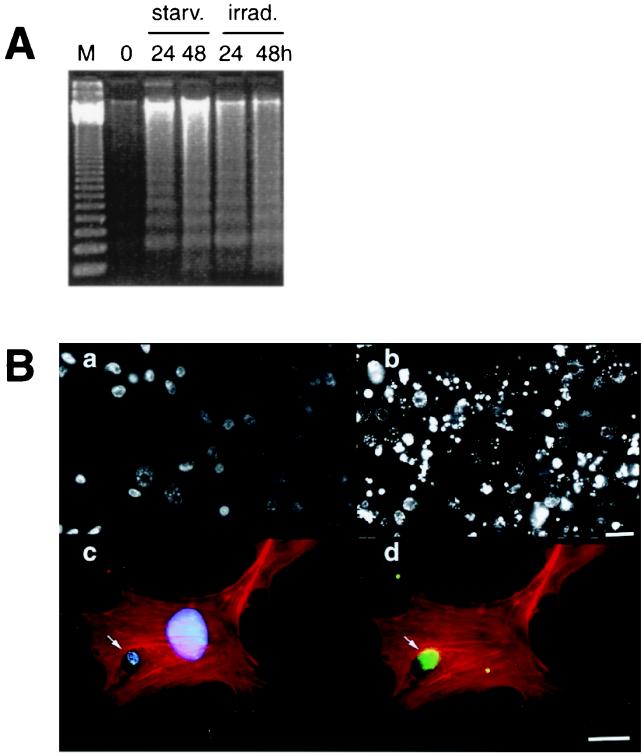

In previous studies, we have shown that integrated viral genes maybe horizontally transferred via the uptake of DNA from apoptotic bodies (13, 14). In this study, we raised the question of whether engulfment of apoptotic bodies derived from cells carrying oncogenes may cause transformation of the recipient cell. Wild-type REF or REFrm cells transfected with the H-rasV12 and human c-myc oncogenes were used as donor cells. Cell death was induced in REF or REFrm by irradiation or by nutrient depletion. Both methods induced ladder formation of DNA purified from the cytoplasmic fraction of the cell lysates (Fig. 1A). In addition, irradiation or nutrient depletion induced nuclear condensation, which is consistent with cell death by apoptosis (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Previous studies have shown that fibroblast cells are capable of ingesting apoptotic bodies by phagocytosis (13). Indeed, addition of apoptotic bodies to MEF resulted in rapid internalization (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Internalization of apoptotic bodies by MEF. (A). Apoptosis was induced in REFrm cells by either nutrient depletion or γ irradiation as shown by DNA fragmentation before (0) or after 24 and 48 h of culture either in nutrient-depleted medium (starv.) or after irradiation (irrad.). M = 123-bp DNA ladder. (B). Hoechst 33258 staining of REFrm cells (a) and REFrm cells 48 h after irradiation (b) showed nuclear condensation after irradiation. F-actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (c and d) to show the phagocytosis of an EGFP-labeled REFrm apoptotic body (arrow) by a MEF. Cellular DNA was stained with Hoechst 33258 (c) and (d), shows the EGFP-positive signal of the phagocytosed REFrm apoptotic body. (Bars: a and b = 15 μm; c and d = 6 μm.)

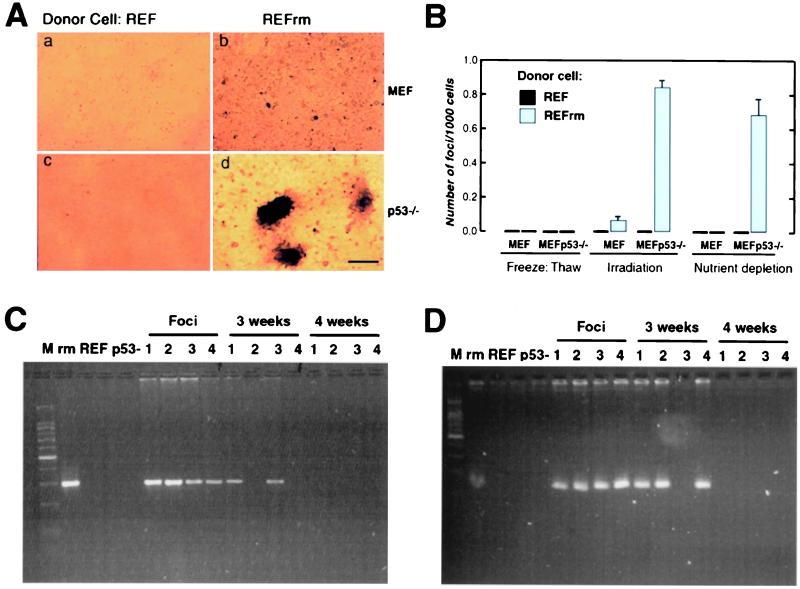

Next, we assessed whether horizontally transferred DNA from apoptotic bodies derived from REFrm cells could induce loss of contact inhibition in MEF. Apoptosis was induced as described, and dying cells were cultured with wild-type MEF. Focus formation could be detected in MEF cells cultured with irradiated REFrm cells (Fig. 2 A and B); however, these cells became senescent or died during propagation. The p53 tumor suppressor gene is considered the guardian of the genome and is activated by DNA damage (23, 24). In addition, transformation of primary rodent cells by the ras oncogene results in accumulation of the p53 protein resulting in permanent G1 arrest and senescence (25). We therefore tested whether inactivation of p53 would influence the frequency of focus formation and facilitate propagation of cells expressing oncogenic ras. Coculture of the MEF p53−/− recipient cells with wild-type REF apoptotic bodies did not result in detectable focus formation (Fig. 2A). However, numerous foci, growing as spheroids, were detected when REFrm apoptotic bodies were cocultured with MEF p53−/− cells (Fig. 2 A and B). The addition of necrotic REFrm cells induced no detectable foci in this assay. The cells derived from the REFrm × MEF p53−/− foci were harvested and could be propagated in vitro. Primers were generated against the transfected H-rasV12 and c-myc genes. These primers did not detect the endogenous mouse or rat genes. PCR analysis showed that all foci were positive for PCR amplification with H-rasV12 - and human c-myc-specific primers (Fig. 2 C and D). However, positive signals gradually disappeared during culture and were lost in all clones after 4 weeks.

Figure 2.

Apoptotic bodies derived from REFrm cells induce focus formation in MEF p53−/− cells. (A) MEF (a and b) or MEF p53−/− cells (c and d) were cocultured with either apoptotic REF (a and c) or REFrm (b and d) and focus formation was analyzed after 8 days in culture. (Bar = 220 μm.) (B) Frequency of focus formation in MEF and MEFp53−/− cells after coculture with necrotic cells or apoptotic REF or REFrm cells. Necrosis was induced by freeze thawing, and apoptosis was induced either by irradiation or by nutrient depletion, as indicated. Results are shown as mean ± SD of three independent experiments (C) and (D). PCR analysis for the presence of H-rasV12 (C) and human c-myc (D) in donor REFrm (rm), REF, recipient MEF p53−/− (p53-), foci (1–4), and the resulting cell lines after 3 and 4 weeks of propagation. M = 100-bp DNA ladder.

Positive Selection Pressure Favors Propagation of Apoptotic DNA.

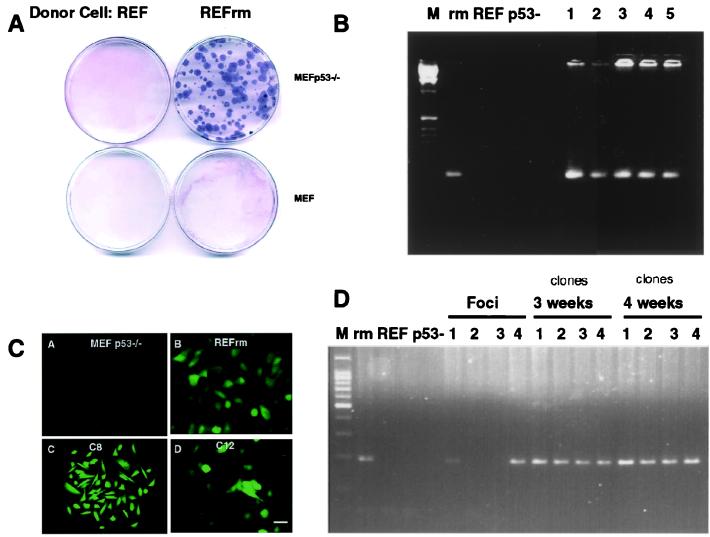

To test whether positive selection pressure would favor propagation of DNA engulfed by phagocytosis, we studied whether uptake of apoptotic bodies would confer resistance to hygromycin drug selection. Apoptosis was induced in the REFrm cells transfected with the gene encoding hygromycin resistance fused to the enhanced green fluorescent marker (Hygr-EGFP) or in REF cells, and the resulting apoptotic cells were incubated with either MEF or MEF p53−/− cells. Hygromycin selection was started after 48 h of culture and was maintained for 4 weeks. In three independent experiments, 90 ± 15 resistant colonies per 10-cm Petri dish were scored in cultures with MEF p53−/− cells fed with REFrm apoptotic cells (Fig. 3A). No resistant colonies were detected in plates with MEF cells incubated with REF apoptotic bodies. PCR analysis showed that the hygromycin-resistant colonies contained the Hygr gene (Fig. 3B). In addition, colonies expressed the Hygr-EGFP fusion protein as detected by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3C). Approximately 60% of the foci derived from REFrm × MEF p53−/− coculture contained the Hygr gene, which, in contrast to the H-rasV12 and c-myc genes, could be maintained during culture in the presence of drug selection (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data suggest that stable propagation of DNA derived from apoptotic cells depends on whether the encoded genes provide a positive selection advantage.

Figure 3.

Induction of hygromycin resistance in MEF p53−/− cells. (A) MEF or MEF p53−/− cells were cultured with apoptotic bodies from REF or EGFP-Hygr expressing REFrm cells. Coomassie staining of hygromycin-resistant MEF p53−/− colonies cultured with REFrm apoptotic bodies is shown. (B) PCR detection of the hygr gene in donor REFrm (rm), REF, recipient MEF p53−/− (p53-), and the hygromycin-resistant REFrm × MEF p53−/− colonies (1–5). (C) Detection of the Hygr-GFP fusion protein in MEF p53−/− recipient cells, REFrm donor cells, and hygromycin-selected REFrm × MEF p53−/− clones C8 and C12. (Bar = 10 μm.) (D) Detection of the hygr gene in foci induced by cultivation of REFrm apoptotic bodies with MEF p53−/− cells. Approximately 60% of the foci were Hygr -positive without hygromycin selection. The Hygr gene could be maintained for over 4 weeks in the presence of hygromycin selection. Positive and negative controls were the same as in B.

Oncogenic Activity of Apoptotic Bodies.

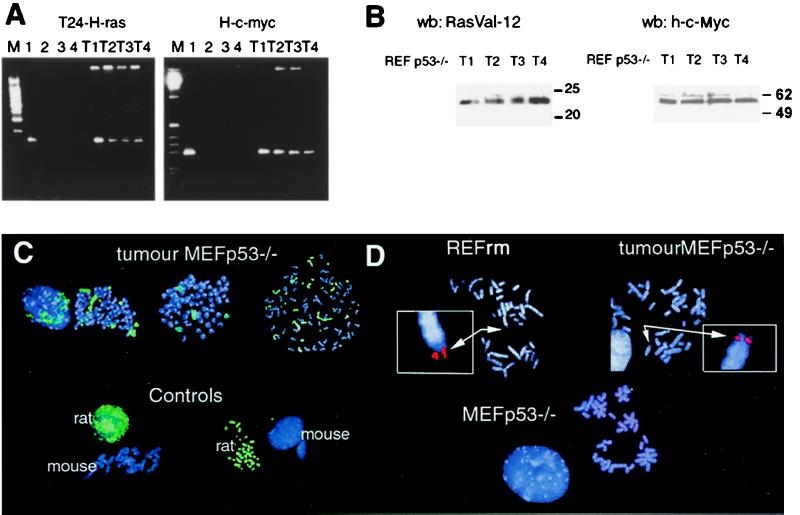

Loss of H-rasV12 and human c-myc DNA during cultivation of cells derived from REFrm × MEF p53−/− foci indicates that the selection pressure did not favor maintenance of the transferred oncogenes in vitro. To test whether transferred oncogenes could be propagated in vivo, we injected REFrm × MEF p53−/− foci into SCID mice. MEF or MEF p53−/− cells cocultured with REF cells were used as negative controls. Tumors were formed within 3 weeks after injection of the cells derived from transformed foci, showing that a fully tumorigenic potential had developed (Table 1). MEF p53−/− cells cultured with nontransformed REF cells did not induce tumor growth. Tumor cells were isolated from the mice and subjected to PCR analysis. H-rasV12 and c-myc DNA as well as the corresponding protein could be detected in all tumors analyzed (Fig. 4 A and B). After the in vivo passage, the transferred oncogenes could be propagated in vitro, which was shown by the fact that the presence of transferred oncogenes in tumor-derived cells was stable for over 3 months in culture and maintained a tumorigenic potential when reinjected into mice (data not shown).

Table 1.

Formation of tumors in SCID mice

| Cells | Number of tumors/number of injections |

|---|---|

| REFrm × MEF p53−/− | 6/10 |

| REF × MEF p53−/− | 0/10 |

| REFrm | 20/20 |

| MEF p53−/− | 0/20 |

Figure 4.

Tumors derived from REFrm × MEF p53−/− foci injected into mice contain the H-rasV12 and human c-myc genes. (A) PCR analysis of H-rasV12 and c-myc DNA in REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors showed presence of these oncogenes in tumors 1–4 (T1-T4). Lane 1 = REFrm, lane 2 = REF, lane 3 = MEF p53−/−, lane 4 = DNA; M = 100-bp ladder. (B) Western blot analysis of H-RasV12 and c-Myc protein expression in REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors (T1-T4). The H-RasV12 antibody is specific to H-RasV12; the c-Myc antibody is specific to human c-Myc and did not crossreact with REF or MEF p53−/− cells. (C) FISH analysis of rat DNA in metaphase spreads from REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors. The FITC-labeled rat DNA painting probe (green) detects rat but not mouse DNA, as shown in the controls. Rat chromosomes as well as rat and mouse hybrid chromosomes could be detected in metaphase spreads from REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors. DNA was counterstained with the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) fluorochrome (blue). (D) Detection of the human c-myc gene in metaphase chromosomal spreads by using a human c-myc-specific rhodamine-labeled probe (red). The human c-myc probe was negative in MEF p53−/− chromosomal spreads but is detected in metaphase spreads from REFrm cells and REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors (arrows). Insets show the positive signal at a 4-fold relative magnification. Blue color shows DAPI DNA staining.

Next we used FISH analysis to investigate how the transferred DNA was propagated in the REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumor cells. To follow the fate of the DNA internalized by phagocytosis, we used a probe that distinguished between the DNA of the donor cells and that of the recipient cells. Rat genomic DNA was labeled with biotinylated-16-dUTP and subsequently used to identify DNA derived from apoptotic bodies. This probe hybridized specifically to rat DNA interphase nuclei or metaphase chromosome spreads with no detectable cross hybridization to mouse DNA (Fig. 4C). Analysis of metaphase spreads from cells derived from REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors revealed the presence of rat chromosomes as well as hybrid rat/mouse chromosomes. In addition, FISH analysis by using a rhodamine-labeled probe specific for the human c-myc gene showed that human c-myc was present in all tumors analyzed (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

In this study, we report that activated oncogenes are transferred in a horizontal manner by the uptake of apoptotic bodies. Uptake of apoptotic bodies derived from H-rasV12- and c-myc-transfected cells induced loss of contact inhibition and anchorage independence, as well as tumorigenicity in SCID mice after transfer to recipient p53−/− cells. In contrast, apoptotic bodies derived from normal REF cells did not affect the growth of the recipient cells in any of these assays. Furthermore, no transformation was detected when apoptotic bodies were cultured with MEF with intact p53, indicating that p53 may protect cells from incorporation of activated oncogenes derived from apoptotic bodies. There are several possible explanations why normal fibroblasts are not transformed by tumor apoptotic bodies. For example, phagocytosed apoptotic DNA may be identified by the cell as damaged DNA resulting in the accumulation of p53 protein that may induce either cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. Previous work has shown that transfection of oncogenic ras in normal fibroblasts results in p53-mediated permanent G1 arrest. In addition, inactivation of p53 in cells in culture has been shown to be correlated with aneuploidy (26), which may explain why whole rat chromosomes are propagated in REFrm × MEF p53−/− tumors (Fig. 4C).

We have further shown that the transferred DNA is lost unless it confers a strong selective advantage to the recipient cell. Interestingly, the H-rasV12 and c-myc genes could not be maintained during continuous propagation in vitro, whereas the Hygr gene could be maintained for more than 4 months in the presence of hygromycin. This may reflect that the transferred DNA is inefficiently replicated in the new host or that there is no selection for these oncogenes in vitro. However, when these cells were injected into SCID mice, all resulting mouse tumors expressed both H-rasV12 and human c-myc. The size of the transferred DNA indicates that the entire genome is not fragmented under the conditions in which the experiments were performed. The fragmentation of DNA as shown in Fig. 1 represents only the soluble fraction of the total DNA and hence shows that only a fraction of the total DNA is fragmented. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown that nuclear condensation and apoptosis are independent of DNA degradation (27–28).

Cancer is a genetic disease that requires the accumulation of genetic alterations necessary for malignancy (29–30). Most tumor cells are genetically unstable, as manifested by the genomic heterogeneity between cells within the tumor. This genetic instability may accelerate tumor progression by promoting mutations that confer a growth advantage. The increase in mutation frequency in cancer cells may be explained by the inactivation of genes involved in maintaining the integrity of the genome. These include the p53 tumor suppressor gene, the mismatch repair genes, and genes involved in controlling the replication and segregation of chromosomes during mitosis (31). We propose that the uptake of DNA via apoptotic bodies may be one possible mechanism by which genetic instability and genetic diversity is generated within a tumor. We speculate that the genetic changes necessary for malignancy may accumulate within tumor cells via horizontal transfer of DNA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society and the Swedish Society of Medicine.

Abbreviations

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- REF

rat embryonic fibroblasts

- REFrm

human myc- and H-rasV12-transfected REF cells

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficient

References

- 1.Kerr J F, Wyllie A H, Currie A R. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyllie A H, Kerr J F, Currie A R. Int Rev Cytol. 1980;68:251–306. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bursch W, Paffe S, Putz B, Barthel G, Schulte-Hermann R. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:847–853. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.5.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bursch W, Taper H S, Lauer B, Schulte-Hermann R. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1985;50:153–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02889898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barres B A, Hart I K, Coles H S, Burne J F, Voyvodic J T, Richardson W D, Raff M C. Cell. 1992;70:31–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90531-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmgren L, O'Reilly M S, Folkman J. Nat Med. 1995;1:149–153. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao L, Debbas M, Sabbatini P, Hockenbery D, Korsmeyer S, White E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7742–7746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evan G I, Wyllie A H, Gilbert C S, Littlewood T D, Land H, Brooks M, Waters C M, Penn L Z, Hancock D C. Cell. 1992;69:119–128. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90123-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe S W, Lin A W. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:485–495. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christofori G, Naik P, Hanahan D. Nature (London) 1994;369:414–418. doi: 10.1038/369414a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lake J A, Jain R, Rivera M C. Science. 1999;283:2027–2028. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ochman H, Lawrence J G, Groisman E A. Nature (London) 2000;405:299–304. doi: 10.1038/35012500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmgren L, Szeles A, Rajnavölgyi E, Klein G, Folkman J, Ernebrg I, Falk K. Blood. 1999;93:3956–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spetz A, Patterson B K, Lore K, Andersson J, Holmgren L. J Immunol. 1999;163:736–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Taille A, Chen M W, Burchardt M, Chopin D K, Buttyan R. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5461–5463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donehower L A, Harvey M, Slagle B L, McArthur M J, Montgomery C A J, Butel J S, Bradley A. Nature (London) 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spector D L, Goldman R D, Leinwand L A. Cells: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih C, Shilo B Z, Goldfarb M P, Dannenberg A, Weinberg R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;11:5714–5718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henriksson M, Bakardjiev A, Klein G, Lüscher B. Oncogene. 1993;8:3199–3209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szeles A, Bajalica-Lagercrantz S, Lindblom A, Lushnikova T, Kashuba V I, Imreh S, Nordenskjold M, Klein G, Zabarovsky E. Chromosome Res. 1996;4:310–313. doi: 10.1007/BF02263683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinkel D, Straume T, Gray J W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2934–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng L, Fu J, Tsukumoto A, Hawley R G. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:606–609. doi: 10.1038/nbt0596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane D P. Nature (London) 1992;358:15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine A J. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serrano M, Lin A W, McCurrach M E, Beach D, Lowe S W. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harvey M, Sands A T, Weiss R S, Hegi M E, Wiseman R W, Pantazis P, Giovanella B C, Tainsky M A, Bradley A, Donehower L A. Oncogene. 1993;8:2457–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberhammer F, Fritsch G, Schmied M, Pavelka M, Printz D, Purchio T, Lassmann H, Schulte-Hermann R. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:317–326. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagata S. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:12–18. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop J M. Cell. 1991;64:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90636-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan D, Weinberg R A. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson A L, Loeb L A. Semin Cancer Biol. 1998;8:421–429. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]