Although nowhere near as endemic a problem as once was the case in India, payments for organ donations, which were made illegal in 1995, have continued to blight the landscape and invited charges that the impoverished are being preyed upon.

When coupled with a severe disparity between supply and demand, inadequate rules to determine which patients should get the donated organs that are available, jurisdictional squabbles between states and the federal government, and the activities of a few unscrupulous medical practitioners fueling illegal traffic in organs, they have made India an outlier in the world of organ donation.

But the national government has taken a step toward containing the havoc by passing legislative amendments that lay the spadework for the creation of a national organ registry and distribution system, complete with rules for determining which patients are most critically in need of transplants.

The legislation establishes the groundwork “for a systematic and scientific method of transplantation of human organs covering the entire country,” says Dr. Anil Kumar, a medical officer in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare who has been charged with setting up the registry. But the “gap between the supply and demand is so wide that it will take some time before the registry can be functional.”

Kumar anticipates the biggest challenge will lie in the development of criteria for determining which patients should be designated as priority recipients of available organs, as well as how exactly to maintain a national waiting list. To that end, Kumar says the team will assess the operations of the United Network for Organ Sharing in the United States, as well as models used by other countries.

Until now, oversight of organ donation in India has been essentially left to the domain of the states, which are responsible for health care, and as a consequence, transplant services are vastly different from region to region. In some areas, attempts have been made to standardize procedures and create mechanisms to determine allocations but in other regions, it seems a free-for-all.

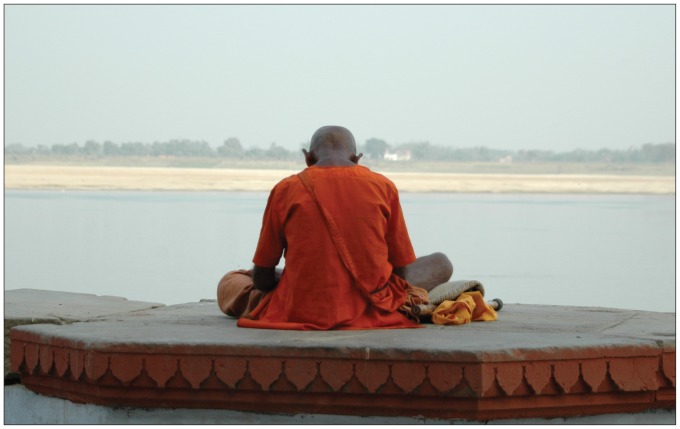

Among the challenges to improving organ donation rates in India is overcoming religious beliefs, such as one which holds that if an organ is removed from the body, a person may be reincarnated with that part missing.

Image courtesy of © 2012 Thinkstock

Also to be determined are what approaches to take to substantially increase organ donation rates in India. Although the government moved with legislation in 1995 to recognize “brain death” as a form of death in a bid to improve rates, and allowed organs to be obtained from the victims of road accidents, donation rates remain abysmal, though India has one of the highest rates of traffic deaths in the world, with 1.3 million fatalities annually, according to the World Health Organization.

Both the national government and private bodies say they do not know what the overall demand for organs in India might be, or what the current organ donation rate is, while the International Register of Organ Donation and Transplantation did not include India in its 2009 update. Unofficial and unconfirmed data suggest that India lags well behind other nations in organ donation rates, at 0.05 donations per million people, or a fraction of the rate of 25 per million in the United States.

But with every nation in the world experiencing higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes, one of the leading causes of kidney failure, demand is only expected to increase.

Framers of the legislation hope that one of its provisions, which compels physicians and health workers to discuss organ donation with relatives of the deceased, will result in more donations.

More promotion and use of donor cards is expected to be among the measures aimed at improving donation rates. Advocates also hope that an offer of free annual health check-ups for donors, and free treatment for complications stemming from donation, will also serve to encourage more donations from living donors.

Among obstacles to be overcome in improving organ donation rates is the common perception that religions forbid organ donation and transplantation, particularly the widespread Hindu belief that if an organ is removed from the body, a person may be reincarnated with that part missing. “We also need to bring together religious gurus and leaders, and spread the message that no religion bars one from donating organs,” Dr. R.K. Sharma, director of the Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, told the Times of India (http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-11-29/delhi/30453963_1_families-of-organ-donors-national-organ-transplant-programme-first-heart-transplant).