Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether macular thickness is associated with ethnicity, gender, axial length and severity of myopia in a cohort of young adults from the Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET).

Methods

Eleven years after their baseline visit, 387/469 (83%) subjects returned for their annual visit. In addition to the protocol-specific measures of spherical equivalent refractive error (SER) and axial length (AL), high-resolution macular imaging also was performed with Optical Coherence Tomography (RTVue). From these scans, full thickness values for the central (1 mm), para- (1–3 mm), and peri-foveal (3–5 mm) annular regions were calculated. Gender, ethnicity, AL, and SER were examined for associations with macular thickness using univariate and multivariable linear regression analyses.

Results

In the 377 subjects with usable data (mean age=21.0 ±1.3 years) the mean SER±SD was −5.0±1.9 D and mean AL was 25.4±0.9 mm. Mean foveal thickness was 252.0± 20.1 µm in the center, 315.6±14.0 µm in the para-fovea, and 284.4±12.9 µm in the peri-fovea. In the best-fit multivariable model that adjusted for gender, ethnicity, and AL, females had significantly thinner maculas than males for all three regions (p<0.0001), with the largest difference in the center (12.8 µm, 95%CI: 9.2 to 16.4). The effect of ethnicity was strongest in the central fovea, with African-Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and mixed ethnic groups thinner maculas than whites (all p-values < 0.005). Increased AL was significantly associated with slightly thicker central foveas (p=0.001) and thinner para- (p=0.02) and peri-foveal (p< 0.0001) regions.

Conclusions

In this ethnically diverse cohort of moderate and high myopes, females and African-Americans were found to have the thinnest central foveas. Whether such thinning in the macula as a young adult is a risk factor for future disease remains to be determined.

Keywords: myopia, optical coherence tomography, macula, fovea, young adults, axial length

Myopia is a risk factor for glaucoma, retinal detachments, and degenerative changes in the central retina, conditions which can lead to significant vision loss.1, 2 Because the prevalence of myopia is increasing, the economic and visual burden of these related diseases may also increase.3 It is therefore important to understand why the myopic eye seems to be more susceptible to disease. Some previous studies have utilized more traditional examination methods, such as binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy.4–6 However, retinal structures can now be visualized in vivo using optical coherence tomography (OCT). 7 The resolution of commercially available OCT systems is approximately 5 to 10 microns, allowing visualization of distinct layers within the retina.8 This technology allows more sensitive and standardized measures of the retina in the living eye, which should enhance our understanding of the pathophysiology of myopia and its relationship to the development of other ocular diseases.

Previous OCT studies have suggested that macular thickness is associated with age, gender, ethnicity, axial length, and refractive error.9–21 These studies have used different instruments and algorithms and include populations that differ by age, gender, ethnicity, country of origin, and refractive status. Despite these differences, most 10,11,15–18 but not all 9,14 studies report that females have thinner maculas than males. In addition, persons of African descent have thinner central foveas and some quadrants of the outer foveal regions compared to other ethnic groups, with some variation among studies.9–15

Some OCT studies, mainly performed in Asia, have explored the potential relationship between macular thickness and axial length and/or amount of myopia.15–21 In these studies, increased axial length has been associated with thicker central foveas17–20 and some thinner quadrants in the para- and peri-foveal regions, 16–20 with one study finding no association.15 Results for refractive error are more mixed; some studies find that myopia is associated with a thicker central fovea and some thinner para- and peri-foveal quadrants, 18–21 while others find no association.15–17 No prior studies have included large numbers of myopic young adults of different ethnic backgrounds.

Data from the Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET) allow the investigation of macular thickness and related factors in a large, multi-ethnic group who were aged 6–11 years with low to moderate myopia when they enrolled in COMET in 1997 and aged 17–22 years at the time of OCT measurements, 11 years later. The purpose of this study is to determine whether macular thickness is related to ethnicity, gender, axial length and amount of myopia in a large cohort of myopic young adults, in which over one-quarter have high myopia (worse than –6.0 D). These data should enhance our understanding of factors associated with macular thickness in individuals with myopia, which has increased in prevalence in recent years to 40% of the population aged 12–54 years living in the United States.3

METHODS

The COMET study design22 and main treatment outcomes23–24 have been described previously. The clinical trial evaluated two lens treatments, single vision (SVL) and progressive addition lenses (PAL), and reported a statistically significant, but not clinically significant, treatment effect of 0.20 D after three years. Children wore study lenses for five years, after which they could wear either spectacle or contact lenses. Currently, COMET is a natural history study of factors associated with myopia progression and stabilization. In the current analyses, data are combined for these two lens treatment groups. During the 11-year study visit, the standard study protocol, including measurements of axial length and cycloplegic refractive error (described below), was followed as described previously.25 In addition to these procedures, high resolution retinal imaging was performed with OCT as described below.

Subjects

Three hundred and eighty seven young adults, aged 17.2 to 23.5 years old at their 11-year study visit, participated at their respective clinical centers (Optometry Schools / Colleges in Birmingham, AL, Boston, MA, Houston, TX, and Philadelphia, PA). The study protocols conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and the institutional review boards at each participating center approved the research protocols. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, after a written and verbal explanation of the clinical procedures.

Standard Study Procedures

As part of the COMET study protocol, cycloplegic refractive error and axial length were measured in all subjects at each annual visit. All measurements were performed by study optometrists who were trained and certified on all procedures. Refractive error was measured 30 minutes after administration of a second drop of a cycloplegic agent (2 drops of 1% tropicamide, separated by 4–6 minutes), using an autorefractor (ARK-700A; Nidek, Japan). Five consecutive reliable measurements were taken in each eye and the mean cycloplegic refractive error, in terms of spherical equivalent, was calculated for each eye.

Axial length was measured by ultrasonography (A-2500; Sonomed, New York, USA) after a drop of anesthetic (1% proparacaine) was placed in each eye. Five consecutive measurements were taken, either using the slit lamp (preferred technique) or handheld technique, in each eye. A standard deviation less than or equal to 0.10 mm between measurements was maintained for each eye. Mean axial length was then calculated for each eye from these measurements.

OCT Imaging

The device (RTVue, Model RT-100, Optovue, Inc. Fremont, CA) used in this study to image the macular region is a Fourier Domain (also known as Spectral Domain) OCT instrument, which can capture 26,000 A scans/second with a depth resolution of 5 µm using a scanning laser diode at a wavelength of 840±10 nm. From these scans, full retina thickness values for nine regions of the macula were observed, as described below and previously in a study using the same instrument.9

In COMET, OCT imaging was performed by the study optometrist in the right eye first, with natural pupils, unless the subject’s pupil size was smaller than 3 mm under dim illumination (n=9). For these 9 subjects OCT imaging was performed with dilated pupils after all other ocular measurements were taken. No optical correction was used when images were taken. To improve image quality, all subjects received one drop of an artificial tear with mild viscosity in each eye prior to imaging. In addition, subject fixation and blinks were monitored during all scans.

To investigate macular thickness, a series of macular scans were taken in a sequential order in each eye; first a 3D reference SLO scan (7 × 7 mm grid), which was used for image registration, followed by three EMM5 (enhanced macular map) scans (5 × 5 mm grid). All scans were individually inspected at the time of measurement to ensure good image quality (Signal Strength Index (SSI) > 50, with no breaks or shearing in the images) and were re-taken, if necessary.

All data were sent to the Coordinating Center for central processing using the RTVue software (version 6.1.04). For each scan the average total retinal macular thickness was computed in microns for the central 1.0 mm area of the fovea and for each of the ETDRS quadrants (nasal, temporal, superior, and inferior) of the para-fovea (inner 1.0–3.0 mm ring) and peri-fovea (outer 3.0 –5.0 mm ring) for a total of 9 regions.

OCT Image Quality

Because of the high consistency in macular thickness values from the right and left eyes (intra-class coefficient (ICC) = 0.92 in the central foveal region and 0.96 in both the para- and peri-foveal regions), only the macular scans of the right eye were used for data analysis and presentation of the results. Of the 387 subjects who were imaged, data from 4 subjects were omitted due to either having only one high-quality (> 50 SSI score) scan available, prior refractive surgery, or missing 11-year axial length data. Therefore, data from 383 subjects were considered for further analysis.

Fixation errors during OCT imaging have been shown to influence macular thickness measures.26–27 While, to our knowledge, there is no clinical rationale for a myopic individual to consistently utilize a non-central foveal fixation point, steps were taken to ensure that the scan sets maintained good within- and between-subject agreement. Specifically, the variability of the macular thickness within each subject’s scan set was evaluated and those with high (top 5%) variability (e.g. due to fixation errors) were flagged and evaluated. This process removed an individual scan from 46 subjects. Between-subject variability was also analyzed and subjects with the highest and lowest average macular thickness values, for at least one of the nine macular regions, were flagged. Flagged data were then compared to the average macular thickness of the subject’s left eye and to those obtained at the next annual visit (data not reported). Scans that were not largely consistent with both the fellow eye and subsequent year average (>10 µm difference) were removed. This process resulted in the removal of 6 scan sets (18 scans in total). Thus, 377 subjects had high quality usable data of whom 329 subjects (87%) had all three scans and 48 (13%) had two scans available for analysis.

In order to assess the reliability of the three scans taken for each subject, ICCs were estimated using linear mixed models (with subject-specific random intercepts). The ICC was high (> 0.97), indicative of highly reliable repeated measurements within a subject’s scan set. The central fovea had the highest within-subject variability (mean SD=2.2), while the superior region of the para-fovea had the lowest (mean SD=1.5). Based on the high reliability of scans within a subject’s scan set, the average macular thickness value for each of the 9 regions across all available scans was used for subsequent data analysis.

Data Analysis

Recently, attention has been paid to the potential effects of retinal magnification on OCT measurements due to differences in axial length.10,27 Given the longer axial lengths of the COMET myopic cohort, a pilot analysis was performed on 196 macular scans in the central, para-foveal and peri-foveal regions from 20 subjects with the shortest (n = 10) and longest (n = 10) axial lengths (range of AL= 21.09 to 22.33 and 27.13 to 27.86 for the two groups). For each region, formulas derived from a previous model eye analysis28 were applied to these data to adjust for axial length. Differences between the unadjusted and adjusted data were then calculated. On average, only small differences in macular thickness were found between the original and adjusted data (≤2 µm in the central 1mm, ≤1 µm in the para-fovea and ≤4 µm in the peri-fovea). These results, therefore, supported the decision to not make axial length adjustments to the full data set. These small differences may be due to the ‘auto-all focus’ feature of the RTVue, which was utilized during imaging in all subjects. This feature automatically estimates the subject’s refraction in diopters and accordingly adjusts the system’s configuration to minimize magnification errors.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2. Subject demographic characteristics, including gender, self-reported ethnicity, and original treatment assignment (PAL vs. SVL) were each evaluated for associations with OCT macular thickness measurements, first in all 9 individual regions and then in the central fovea, para-fovea, and peri-fovea, based on the average of the quadrants within each of the latter two regions. Level of myopia, as measured by cycloplegic autorefraction, and axial length were also evaluated in both a categorical and continuous fashion for each of the three foveal regions. Specifically, level of myopia, using a clinically relevant cut-point of high myopia (worse than −6D) that has been used previously to describe the COMET cohort, 29 was used to examine for associations between high myopia and macular thickness. Subject axial length was evaluated in a similar way, but classified based on a median split of the cohort’s axial length to distinguish between shorter and longer eyes. Visual acuity and subject age were not evaluated for associations with macular thickness given the narrow ranges of the cohort.

Descriptive statistics (e.g., count, mean, standard deviation) were generated for all OCT outcomes and subject characteristics. Retinal maps showing average thickness values, for each of the 9 ETDRS quadrants, and scatter plots were generated in order to visually characterize the data. ICCs were computed to estimate the overall correlation across the thickness measurements for the quadrants within the para- and peri-foveal regions.

The associations between subject characteristics and macular thickness were evaluated using linear regression and corresponding Wald test p-values. Univariate (unadjusted) analyses were performed initially to evaluate independent associations with gender, ethnicity, axial length, and spherical equivalent myopia (SER). Several multivariable models were then examined to assess the effects of potential risk factors when analyzed jointly. Covariates under consideration for the final multivariable models included gender, ethnicity, axial length, and SER. The final models were selected to maximize the proportion of explained variation (R2) while only including statistically significant factors (p-value < 0.05). The adjusted parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals from the model are presented along with the corresponding p-values based on the Wald test.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows demographic and ocular characteristics as well as the mean macular thickness values for the central fovea and for each quadrant of the para- and peri-foveal regions of the right eyes of 377 COMET subjects. The mean (± SD) age of the group at the time of OCT measurements was 21.0±1.3 years, mean axial length was 25.4±0.9 mm, and mean SER was −5.0±1.9 D. There were more females than males (55% vs. 45%) and the breakdown of self-reported ethnicity was as follows: African-American (28%), Asian (8%), Hispanic (14%), mixed (6%) and white (45%), which was similar to that of the full COMET cohort.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the COMET cohort (n=377) at their 11-year study visit.

| Characteristics | n (%) | Mean (SD) | (min, max) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 21.0 (1.3) | (17.2, 23.5) | ||

| Gender | Female | 206 (55) | ||

| Male | 171 (45) | |||

| Ethnicity | African-American | 104 (28) | ||

| Asian | 31 (8) | |||

| Hispanic | 53 (14) | |||

| Mixed | 21 (6) | |||

| White | 168 (45) | |||

| Ocular measurements | ||||

| Axial length (mm) | 25.4 (0.9) | (22.1, 28.0) | ||

| Spherical Equivalent Refractive Error (Diopters) | −5.0 (1.9) | (−1.0, −11.2) | ||

| Macular thickness measurements | ||||

| Central fovea thickness (µm)§ | 252.0 (20.1) | (192.0, 316.5) | ||

| Average para-fovea thickness (µm)§ | 315.6 (14.0) | (267.3, 355.2) | ||

| Para-fovea Quadrants*: | ||||

| Temporal | 306.6 (14.7) | (259.0, 348.3) | ||

| Superior | 319.5 (13.9) | (273.0, 358.7) | ||

| Nasal | 321.3 (14.8) | (272.0, 360.0) | ||

| Inferior | 314.9 (14.5) | (262.7, 357.0) | ||

| Average peri-fovea thickness (µm)§ | 284.4 (12.9) | (244.1., 320.6) | ||

| Peri-fovea Quadrants*: | ||||

| Temporal | 276.4 (14.1) | (233.3, 317.5) | ||

| Superior | 284.3 (13.4) | (239.7, 320.0) | ||

| Nasal | 301.1 (14.7) | (247.7, 341.7) | ||

| Inferior | 275.7 (13.4) | (240.7, 312.3) | ||

Statistically significant (p= 0.0001) difference compared to any other region (central, para-, peri-fovea)

Statistically significant (p=0.0001) difference in quadrants from the same region based on an overall Wald test

As shown in Table 1, the central fovea was the thinnest of the three macular regions, with a mean of 252.0±20.1 µm. The average macular thickness of the para-foveal region was 315.6±14.0 µm and was 284.4±12.9 µm in the peri-foveal region. All observed pair-wise comparisons in macular thickness across these three foveal regions were statistically significant (p= 0.0001). Mean thickness also varied across quadrants within the para- and peri-foveal regions. In the para-fovea the temporal quadrant was the thinnest (306.6±14.7µm) and the nasal quadrant was the thickest (321.3±14.8 µm) (p<0.0001). Significant differences in average thickness also were observed across the quadrants of the peri-fovea (p<0.0001), with the inferior quadrant the thinnest (275.7±13.4 µm) and the nasal quadrant the thickest (301.1±14.7 µm).

Figure 1 shows the average thickness value for each of the 9 ETDRS macular regions stratified by gender. Shaded regions indicate statistically significant differences between males and females. Females had consistently thinner maculas than males (p<0.001 for all regions except peri-fovea, superior and inferior, where p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Macular thickness measurements (mean ± SD) for each region by gender. The innermost circle represents the central 1.0 mm of the fovea, the inner ring represents the para-foveal region (1.0 – 3.0 mm), and the outer ring represents the peri-foveal region (3.0 – 5.0 mm).

Figure 2 shows the average thickness value for each of the 9 ETDRS macular regions stratified by African-American, Hispanic and white ethnic groups. African-Americans had significantly thinner central foveal values compared to whites (p<0.001). Similarly, in the para-fovea African-Americans had significantly thinner macular values than whites in all quadrants (nasal and inferior: p< 0.001, temporal and superior: p<0.05), with no significant differences in the peri-fovea. Hispanics had significantly thinner values than whites in the central fovea, three of the four para-foveal quadrants (all but superior), and also in the temporal peri-foveal quadrant (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Macular thickness measurements (mean ± SD) for each region (as defined in the Figure 1 caption) by ethnicity.

Although there are statistically significant differences across quadrants with respect to mean macular thickness (Figures 1 and 2), there is also a high level of consistency across measurements from quadrants in the same foveal region from the same subject. This was quantified by comparing the variability across quadrants within a subject to the variability across quadrants for the entire cohort. This analysis yielded a high ICC value for each region (para-fovea ICC=0.91, peri-fovea ICC=0.82), and thus allows for the representation of the para- and peri-foveal regions as an average of their four respective quadrants. In addition, the main results did not vary in a meaningful way when comparing this combined approach to quadrant-specific analyses.

Table 2 shows the univariate associations between the average macular thickness of the three foveal regions (central, para- and peri-fovea) and gender, ethnicity, axial length and SER, the latter two evaluated as categorical variables. In the central fovea, gender and ethnicity were significantly associated with macular thickness, as also observed in Figures 1 and 2. The mean central foveal thickness in females of 245.0 µm was significantly lower than in males (mean thickness of 260.4 µm, with a mean difference ± SE of 15.4±1.9 µm; p< 0.0001). For ethnicity, whites had the thickest mean central foveal value of 259.8 µm, and African-Americans had the thinnest value of 242.5 µm. Intermediate values were observed in Hispanics (250.8 µm), Asians (247.1 µm) and mixed (247.7 µm) ethnic groups. Each ethnic group had significantly thinner central foveas compared to whites, with the largest difference observed with African-Americans (mean difference: 17.3±2.3 µm; p-value < 0.0001), followed by Asians (mean difference: 12.7±3.7 µm; p=0.0005), mixed (mean difference: 12.0±4.3 µm; p=0.006) and finally Hispanics (mean difference: 9.0±3.0 µm; p=0.002). The difference in central foveal thickness between African-Americans and Hispanics also was statistically significant (p<0.05), with an 8.3µm difference between the two groups, on average. No other significant pairwise differences between ethnic groups in central foveal thickness were observed. In addition, subjects with an axial length longer than 25.33 mm (based on a median split of the cohort) had significantly thicker central foveas than subjects with shorter eyes (mean difference: 5.3±2.1 µm; p<0.01). Similarly, subjects with myopia worse than −6.0 D had significantly thicker central foveas (255.7 µm) compared to subjects with less myopia (250.6 µm, mean difference: 5.0±2.3 µm; p<0.05). The original lens treatment assignment was not associated with macular thickness in any foveal region (data not shown).

Table 2.

Associations1 between subject demographic and ocular characteristics and central, para-foveal and peri-foveal thickness.

| Characteristic | Central fovea | Para-fovea | Peri-fovea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean µm SE) |

Difference (SE)* |

p-value2 | Mean µm (SE) |

Difference (SE)* |

p-value2 | Mean µm (SE) |

Difference (SE)* |

p-value2 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 206 | 245.0 (1.3) | −15.4 (1.9) | <0.0001 | 310.3 (0.9) | −11.6 (1.3) | <0.0001 | 282.1 (0.9) | −4.9 (1.3) | 0.0002 |

| Male (reference) | 171 | 260.4 (1.4) | - | - | 321.9 (1.0) | - | - | 287.0 (1.0) | - | - |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| African-American | 104 | 242.5 (1.8) | −17.3 (2.3) | <0.0001 | 313.0 (1.4) | −5.5 (1.7) | 0.001 | 283.8 (1.3) | −1.9 (1.6) | 0.23 |

| Asian | 31 | 247.1 (3.4) | −12.7 (3.7) | 0.0005 | 315.5 (2.5) | −3.0 (2.7) | 0.27 | 285.1 (2.3) | −0.6 (2.5) | 0.82 |

| Hispanic | 53 | 250.8 (2.6) | −9.0 (3.0) | 0.002 | 313.2 (1.9) | −5.3 (2.2) | 0.02 | 283 (1.8) | −2.6 (2.0) | 0.20 |

| Mixed | 21 | 247.7 (4.1) | −12.0 (4.3) | 0.006 | 311.2 (3.0) | −7.3 (3.2) | 0.02 | 278.8 (2.8) | −6.8 (3.0) | 0.02 |

| White (reference) | 168 | 259.8 (1.4) | - | - | 318.5 (1.1) | - | - | 285.7 (1.0) | - | - |

| Axial Length3 (mm) | ||||||||||

| Longer eyes (≥25.33 mm) | 189 | 254.7 (1.4) | 5.3 (2.1) | 0.009 | 315.1 (1.0) | −1.0 (1.4) | 0.50 | 282.1 (0.9) | −4.4 (1.3) | 0.0008 |

| Shorter eyes (<25.33 mm) | 188 | 249.3 (1.5) | - | - | 316.1 (1.0) | - | - | 286.6 (0.9) | - | - |

| High myopia (worse than −6D) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 103 | 255.7 (2.0) | 5.0 (2.3) | 0.03 | 314.6 (1.4) | −1.4 (1.6) | 0.40 | 281.9 (1.3) | −3.3 (1.5) | 0.02 |

| No | 274 | 250.6 (1.2) | - | - | 316.0 (0.8) | - | - | 285.3 (0.8) | - | - |

Estimated difference in macular thickness (µm) from reference group

Associations are based on linear statistical models using macular thickness as the outcome variable

p-values correspond to the Wald test for a non-null model coefficient

Based on median split of the data (25.33mm)

For the para-foveal region, similar associations with gender and ethnicity were found. Specifically, females (mean thickness = 310.3 µm) had thinner para-foveal regions, on average, compared to males (mean difference: 11.6±1.3 µm; p<0.0001). Whites (mean thickness = 318.5 µm) had thicker para-foveal regions compared to African-Americans (mean difference: 5.5±1.7 µm; p=0.001), Hispanics (mean difference: 5.3±2.2 µm; p=0.02) and mixed ethnicity (mean difference: 7.3±3.2 µm; p=0.02). No other pairwise differences between ethnic groups in para-foveal thickness were observed. In this region, there was no association between macular thickness and axial length or high myopia.

Similar to the central and para-foveal regions, females (mean thickness = 282.1 µm) had thinner peri-foveal values than males (mean difference: 4.9±1.3 µm; p=0.0002). However, unlike the central and para-foveal regions, ethnicity was not generally associated with overall peri-foveal thickness, except for the mixed group (mean thickness = 278.8 µm), which had thinner values than whites (mean difference: 6.8±3.0 µm; p=0.02). Regarding axial length, in contrast to the central fovea where longer eyes were associated with thicker values, in the peri-fovea, those with longer eyes had thinner values (mean difference: 4.4±1.3 µm p=0.0008). Similarly, subjects with high myopia (mean thickness = 281.9 µm) had thinner peri-foveal values, compared to those with low myopia (mean difference: 3.3±1.5 µm; p=0.02).

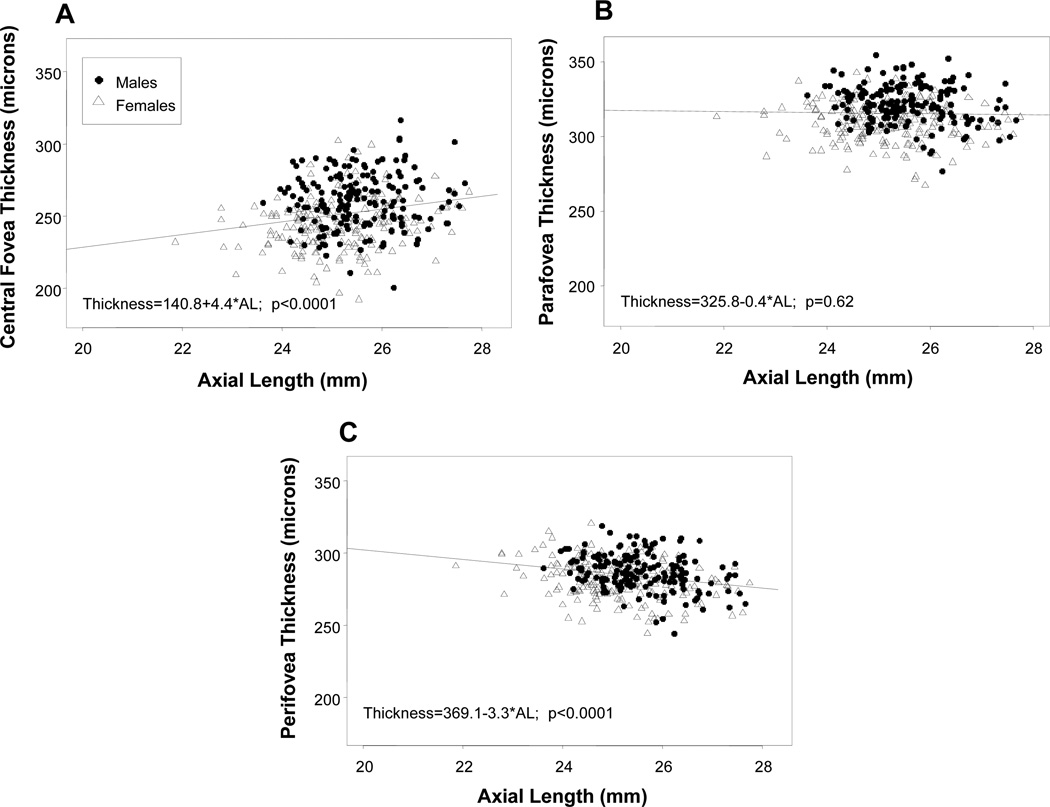

The associations between macular thickness at each foveal region and axial length (mm) as a continuous covariate are shown in Figure 3 (a–c). Although there was individual variability, increased axial length was statistically significantly associated with increased central foveal thickness (slope = 4.4, p=0.009) and reduced peri-foveal thickness (slope = − 3.3, p=0.0008). There was no association between axial length and para-foveal thickness, as demonstrated by the shallow slope (slope=−0.4, p=0.6). In these figures, the difference in axial length between males and females can also be observed, with females having shorter eyes.

Figure 3.

(a–c): Scatter plots of the association between macular thickness and axial length, in both males (filled circles) and females (open triangles), in the central fovea (a), para-fovea (b) and peri-fovea (c).

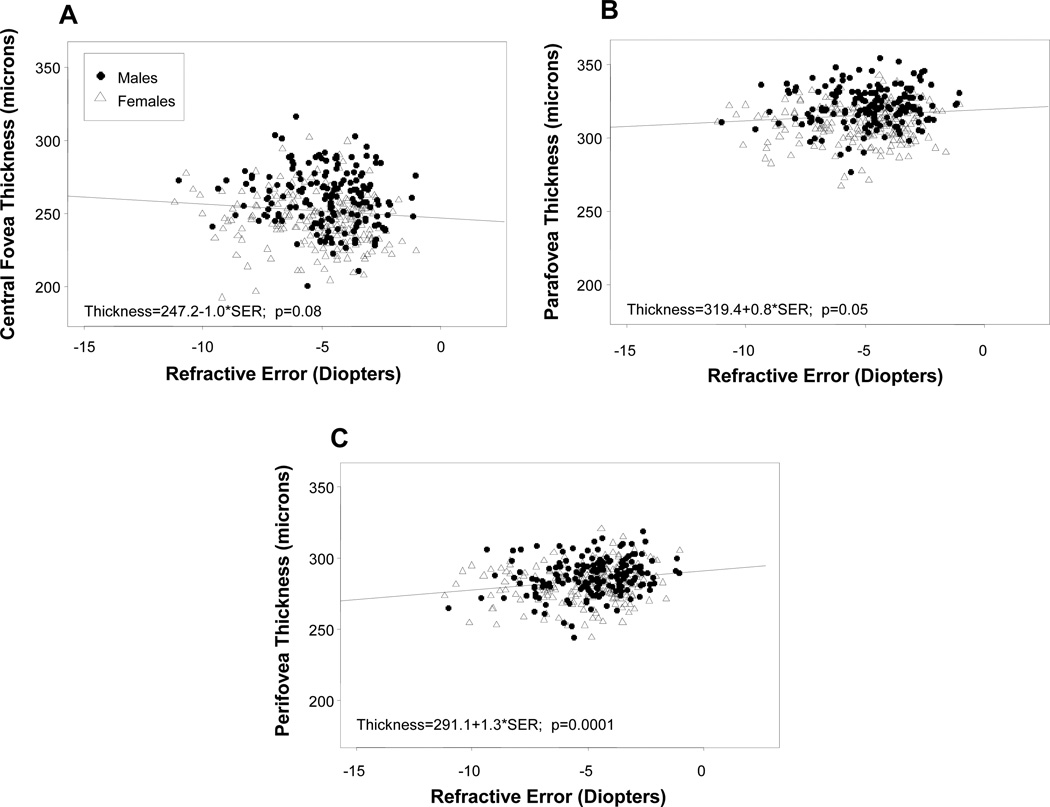

The associations between macular thickness at each foveal region and amount of myopia as a continuous covariate are shown in Figure 4 (a–c). Similar to axial length, increased amount of SER myopia was marginally associated with increased central foveal thickness (slope= −1.0, p=0.08 and reduced peri-foveal thickness (slope = 1.3, p=0.0001). However, unlike for axial length, increased SER was significantly associated with reduced para-foveal thickness (slope=0.80, p=0.05).

Figure 4.

(a–c): Scatter plots of the associations between macular thickness and spherical equivalent refractive error, in males (filled circles) and females (open triangles) in the central fovea (a), para-fovea (b) and peri-fovea (c).

Multivariable models were examined for each of the three macular regions to determine those factors that would remain associated with macular thickness after adjustment for other covariates. Axial length and SER were evaluated as continuous variables for these analyses due to their observed linear relationships with macular thickness (Figures 3 and 4). Although SER was moderately correlated with axial length measured at the same visit (Pearson’s rho=−0.61) and was independently or marginally associated with macular thickness when adjusted for gender and ethnicity (p-values = 0.02, 0.11, and 0.0003 for central, para- and peri-fovea thickness, respectively), it was generally a weaker predictor of macular thickness and did not add any independent information to the multivariable model after adjustment for axial length. Therefore, the final representative model for each region consisted of gender, ethnicity and axial length (mm) but not SER.

Table 3 shows the model-based estimates of thickness differences (from the reference group) for each region, as well as the 95% confidence intervals (CI) and corresponding p-values for each of the 3 covariates, gender, ethnicity and axial length. These final models (one for each macular region) accounted for a moderate percentage of the total variability in macular thickness values, especially in the central foveal region (R2=0.28), and to a lesser extent for the para- (R2=0.21) and peri-foveal (R2=0.13) regions.

Table 3.

Estimated differences in central, para-foveal, and peri-foveal thickness from a multivariable model including ethnicity, gender, and axial length.

| Characteristic | N | Central fovea (R2=0.28) |

Para-fovea (R2=0.21) |

Peri-fovea (R2=0.13) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Estimate (µm) (95% CI)* |

p-value | Model Estimate (µm) (95% CI)* |

p-value | Model Estimate (µm) (95% CI)* |

p-value | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 206 | −12.8 (−16.4,−9.2) | <.0001 | −12 (−14.7,−9.4) | <.0001 | −6.6 (−9.1,−4.0) | <.0001 |

| Male(reference) | 171 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| African-American | 104 | −15.9 (−20.1,−11.6) | <.0001 | −4.3 (−7.4,−1.2) | 0.01 | −1.4 (−4.4,1.6) | 0.36 |

| Asian | 31 | −11.9 (−18.5,−5.2) | 0.0005 | −0.7 (−5.6,4.2) | 0.78 | 1.7 (−3.0,6.4) | 0.47 |

| Hispanic | 53 | −9.7 (−15.0,−4.4) | 0.0004 | −5.1 (−9.0,−1.2) | 0.01 | −1.9 (−5.7,1.8) | 0.32 |

| Mixed | 21 | −11.7 (−19.5,−3.8) | 0.004 | −5.2 (−11.0,0.5) | 0.08 | −4.5 (−10.1,1.0) | 0.11 |

| White(reference) | 168 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

Axial length (continuous, mm) |

277 | 3.1 (1.2,5.1) | 0.001 | −1.7 (−3.1,−0.3) | 0.02 | −4.1 (−5.5,−2.8) | <.0001 |

Estimated slope coefficient and corresponding 95% confidence interval based on a linear statistical model using macular thickness as the outcome variable and ethnicity, gender, and axial length as model covariates.

In the central fovea, results were similar to those observed in the univariate analysis. The central fovea was thinner in females than males by 12.8 µm (CI: 9.2,16.4; p<0.0001). Additionally, macular thickness was lower in each ethnic group compared to whites, with estimated differences ranging from 15.9 µm (p < 0.0001) for African-Americans, to 9.7 µm (p=0.0004) for Hispanics. Central foveal thickness was also associated with increasing axial length (estimated difference [CI]: 3.1 µm [1.2, 5.1]; p=0.001), such that a 1.0 mm increase in axial length was associated with a 3.1µm increase in central foveal thickness (p=0.001). In the para-foveal region, females had thinner maculas compared to males (estimated difference [CI]: 12.0 µm [9.4, 14.7]; p<0.0001). Compared to whites, African-Americans (estimated difference [CI]: 4.3 µm [1.2, 7.4]; p=0.01) and Hispanics (estimated difference [CI]: 5.1 µm [1.2, 9.0]; p<0.0001) had slightly but significantly thinner para-foveas. Axial length was associated with a small but statistically significant thinning in the para-foveal region (estimated difference [CI]: 1.7 µm [0.3, 3.1]). In the peri-foveal region, females consistently had thinner maculas compared to males (estimated difference [CI]: 6.6 µm [4.0, 9.1]; p–003C0.0001). However, ethnicity was not related to macular thickness (adjusted overall p-value =0.19). Finally, increased axial length was associated with more pronounced thinning in the peri-foveal region (estimated difference [CI]: 4.1 µm [2.8, 5.5]; p<0.0001), as compared to the para-foveal region.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Macular thickness was measured in the COMET cohort of 377 myopes eleven years after the baseline visit (mean age of 21 years) and evaluated for associations with gender, ethnicity, axial length and level of myopia in the central, para-, and peri-foveal regions. Overall, the central fovea was found to be considerably thinner than either the para-foveal (64 µm) or peri-foveal (32 µm) regions on average. With respect to demographic characteristics the most consistent finding over all three regions was that females had thinner maculas than males. Self-reported African-Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and mixed participants had thinner central foveas than whites, with differences between African-Americans, Hispanics and whites found in the para-fovea and no ethnic differences in the peri-fovea. In univariate analyses longer axial length and high myopia defined as categorical variables were both associated with thicker central foveas and thinner peri-foveal regions. In a multivariable model the macular thickness differences in gender, ethnicity and axial length (defined as a continuous variable) remained after adjustment for the other factors, while myopia did not add any additional information. In general, all of these differences were greater at the central fovea and decreased in the peripheral regions.

Comparisons with Other Studies

While there has been a recent emergence of studies investigating various retinal characteristics through the use of OCT, it is difficult to compare mean measurements across studies due to differences in subject populations, OCT devices, and definitions of macular regions. In addition, unlike in the present study, some earlier studies took only one OCT scan on each eye and/or used all images, regardless of image quality, potentially contributing to more variable data. Only a few studies corrected for axial length, but previous work with the RTVue instrument has shown that any magnification effects attributable to increased axial length, in the range of the COMET cohort, are negligible.28 Even with these procedural differences and limitations in some studies, consistent findings related to demographic and ocular characteristics have been reported. Table 4 compares OCT findings on macular thickness from 13 recent studies in addition to COMET. In this table only results for the central fovea are presented because that area is more consistently defined in the same way (e.g., central 1.0 mm) across studies.

Table 4.

Summary table of central fovea thickness from the current study and past OCT studies.

| STUDY | SUBJECT CHARACTERISTICS | DEVICE | FACTOR INFLUENCE ON CENTRAL FOVEAL THICKNESS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Age (yrs) | Refractive Error (SE(D)) | Ethnicity | Gender | Axial Length | Refractive Error | Ethnicity | ||

| COMET (2011) | n=377 (377 eyes) | 17–23 | −5.0±1.9 (−1.00 to−11.00) | AA, W, H, A, O | RTVue | M>F | L>S | M>NM | W>H>AA |

| Girkin(2011)9 | n=350 (632 eyes) | 18–84 | −0.6±1.82* | AA, W, H, I, A | RTVue | No correlation | - | - | W=J>AA=H>I |

| Wagner-Schuman (2011)10 | n=90 (180 eyes) | 27.8±9.0 | - | W, AA | Cirrus | M>F | - | - | W>AA |

| Kashani(2010)11 | n=126 (252 eyes) | 49±2.0 | - | W, AA, H | Stratus | M>F | - | - | W=H > AA |

| Song (2010)16 | n=198 (198 eyes) | 55.6±16.4 (17–83) | −2.17±4.8 (+3.75 to −23.5) | A | Cirrus | M>F | No correlation | No correlation | - |

| Cheng (2010)21 | n=61 (61 eyes) | 18–30 | NM= +0.44±0.7 (+2.75 to −0.50 M=−7.88±1.8 (−6.00 to−13.6) |

A | Stratus | - | - | M>NM | - |

| Duan (2010)17 | n=2230 (2230 eyes) | 46.4±9.9 (30–85) | −0.07±0.9 | A | Stratus | M>F | L>S | No correlation | - |

| ADAGES (2010)12 | n=648 (605 eyes) | AA:45.1±13.3 C:47.7±15.9 |

- | AA, W | Stratus | - | - | - | W>AA |

| El-Dairi (2009)13 | n=286 (286 eyes) | 8.59±3.1 (3–17) | AA: +0.27 C: +0.77 | W, AA, O | Stratus | - | - | - | W>AA |

| Grover (2009)14 | n=50 (50 eyes) | 20–84 | - | AA, W, A | Spectralis | No correlation | - | - | W=A>AA |

| Wu (2008)19 | n=73 (120 eyes) | 18–40 | NM: −0.22±0.5(+0.5 to −1.25) HM: −9.27±3.3 (−6 to −15.5) |

A | Stratus | - | L>S | HM>NM | - |

| Kelty (2008)15 | n=83 (166 eyes) | 36.8±12.1(22–75) | −1.9±2.5 | AA, W | Stratus | M>F | No correlation | No correlation | W>AA |

| Luo (2006)18 | n=104 (208 eyes) | 11.5±0.5 | −1.38±1.6(+1.10 to −4.5) | A | Stratus | M>F§ | L>S§ | M>NM§ | - |

| Lim (2005)20 | n= 130 (260 eyes) | 31.2±1.1(19–24) | −5.9±3.5 (−0.25 to −14.25) | A, I | 1st Gen. Zeiss | Males Only | L>S§ | M>NM§ | - |

Approx. SER calculated from sphere reported for each ethnic group.

Minimum foveal thickness

W=White, H=Hispanic, I=Indian, A= Asian, O= Other, L= Longer, S= Shorter, M= Myopes, NM= Non-myopes, HM = High-myopes

Gender

The COMET finding of thinner macular regions in females vs. males is consistent with results from all but two of the seven studies listed in Table 4 that evaluated gender, with the other two reporting no gender differences. A potential explanation for why females have thinner macular regions could be related to their shorter axial length.25, 30–31 In COMET, the gender differences in axial length are an unlikely explanation for the current results since the multivariable analyses included axial length as a covariate. Furthermore, in a different study of an older cohort Wagner-Schumann et al., after correcting for axial length during imaging, also found that females had thinner maculas than males. 10 They also reported that there were no significant gender differences in foveal pit morphology that could account for this finding.10

The clinical significance of females having thinner maculas at both young and old ages is unclear. Females also have been reported to have reduced choroidal thickness compared to males.32 These findings, taken together, suggest that thinner retinas in females may play a role in their greater progression of myopia early in life 33 and increased rate of age-related macular degeneration at older ages.34 While there is no doubt that these ocular conditions are multi-factorial, macular thinning at the posterior pole may be a pre-disposing risk factor for some ocular diseases.

Ethnicity

The main finding related to ethnicity in COMET is that whites have thicker central foveas than the other ethnic groups. Ethnic differences between whites, African-Americans, and Hispanics are also found in the para-fovea. These associations between ethnicity and macular thickness are consistent with previously reported literature, as shown in Table 4. The most striking finding is that African-Americans have thinner foveas than other ethnic groups. Even though individuals of African descent have shorter axial lengths compared to whites,10 this difference does not explain the macular thickness differences because reduced macular thickness in African-Americans remains after adjustment for axial length in COMET and other studies.9–10 Wagner-Schumann et al found ethnic differences in foveal pit morphology, with African-Americans having significantly deeper (15µm on average) and wider (19µm on average) foveal pits compared to white subjects.10 While morphology of the foveal pit was not examined in the COMET cohort, this finding could help to explain the reduced foveal thickness found in African-American participants in COMET and other studies.

Axial Length

The availability of macular thickness and axial length data in the COMET cohort allowed for an investigation into the possible association between these factors. COMET participants with longer axial lengths showed thicker central foveas and thinner para- and peri-foveal regions in a multivariable model. As shown in Table 4, an association between macular thickness and axial length, with longer eyes having thicker central foveas, has been described in four previous studies that investigated this association, while two other studies found no correlation.

Refractive Error

In COMET, given the correlated nature of the relationship between refractive error and axial length, spherical equivalent myopia was not found to contribute any additional information beyond axial length to the final multivariable models presented. As shown in Table 4, some earlier studies found no correlation between central foveal thickness and refractive error while others reported that myopic (or highly myopic) eyes had thicker central foveas. The latter finding is consistent with our univariate results; COMET participants with high myopia (worse than −6.0D) had thicker central foveas and thinner peri-foveal regions compared to subjects with lower amounts of myopia.

A possible explanation as to why this morphology (thicker in the center – thinner in the periphery) exists in high myopes with long eyes has been suggested by Wu et al.19 They propose that as the eye stretches with increased axial length, an increased tangential force across the retinal surface causes the foveal pit to become shallower while the peripheral macula thins. This explanation is consistent with the COMET data as well as with previous reports of decreased macular volume16,18–19 and foveal pit depth10 in myopes.

Clinical Significance

While statistically significant differences in macular thickness were associated with gender, ethnicity, and axial length in the COMET myopic cohort, the clinical relevance of these differences is unclear. The differences found with ethnicity and gender, especially in the central fovea, were large (9–17 µm), outside of the range of repeatability of the instrument, and thus likely to have clinical significance. However, longer axial length was associated with smaller differences in macular thickness (e.g., a 1.0 mm increase in axial length was associated with a 3.1 µm increase in central foveal thickness), a relationship that may not be clinically meaningful. Because the field of OCT imaging is relatively new, no clear consensus exists as to what is a clinically relevant difference in macular thickness.

Given that the COMET cohort at the time of macular thickness measurements consisted of young adults and the exclusion criteria for the clinical trial phase of the study eliminated potentially diseased eyes, the data were collected from healthy eyes. A limitation of some previous studies of macular thickness is the large range in subject age, which could allow for inclusion of some diseased eyes and/or those with age-related retinal changes. The addition of macular thickness data from the ethnically diverse COMET cohort of healthy eyes may contribute to the development of ethnic-specific normative databases. Currently, normative databases within OCT instrumentation are not ethnic-specific, thus the findings from this study can help to optimize OCT instrumentation and diagnostic accuracy. This is particularly important given the increased risk that some ethnic groups, namely those of African descent, have for various blinding ocular diseases, including open angle glaucoma, 35–36 cataract and diabetic retinopathy.36 While optic disc area has been described as being larger in those of African descent,12,37 this finding could not explain the macular thickness differences observed in a previous study12 and is unlikely to be an explanation for the present results.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, in this ethnically diverse young adult myopic cohort, we have described associations between macular thickness and several characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, axial length, and level of myopia. One of the most significant findings is the association of thinner maculas in females, which was consistent across all regions of the fovea. Another significant finding is that thinner maculas were found in African-Americans and Hispanics in the central fovea and para-fovea as compared to whites. In general, the differences found in macular thickness are more pronounced in the central fovea, and decrease as measurements are made further out into the peripheral fovea. Moreover, gender, ethnicity, and current axial length provide a moderate prediction of central foveal thickness, when used in multivariable modeling. Given that myopic individuals are more at risk for retinal diseases and that many OCT studies have not investigated macular thickness in an ethnically diverse population of healthy, myopic young adults, the current data may make a contribution to ethnic-specific normative databases for myopic eyes. In addition, the Multi-Center Observation of Non-Myopic Subjects Study (MOONS), an ancillary study to COMET, is underway at all COMET study sites. This age-, gender-, and ethnicity-matched population will allow us to compare various ocular measurements, including those presented here, between myopic and non-myopic young adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Nancy Coletta, Li Deng and Optovue for helpful discussions.

Funded by NEI/NIH Grants EY11756, EY11805, EY11754, EY11740, EY11752 and EY11755.

COMET STUDY GROUP

Study Chair: J. Gwiazda (Study Chair/PI); T. Norton; K. Grice (9/96-7/99); C. Fortunato (8/99-9/00); C. Weber (10/00-8/03); A. Beale (11/03-7/05); D. Kern (8/05-8/08); S. Bittinger (8/08-4/11); R. Pacella (10/96-10/98).

Coordinating Center

L. Hyman (PI); M. C. Leske (until 9/03); M. Hussein (until 10/03); L. M. Dong (12/03-5/10); M. Fazzari (5/11-present); L. Dias (6/98-present); E. Schoenfeld (until 9/05); R. Harrison (4/97-3/98); W. Zhu (until 12/06); K. Zhang (04/06-present); Y. Wang (1/00-12/05); A. Yassin (1/98-1/99); E. Schnall (11/97-11/98); C. Rau (2/99-11/00); J. Thomas (12/00-04/04); M. Wasserman (05/04-07/06); Y. Chen (10/06-1/08); S. Ahmed (1/09-6/11); L. Passanant (2/98-12/04); M. Rodriguez (10/00-present); A. Schmertz (1/98-12/98); A. Park (1/99-4/00); P. Neuschwender (until 11/99); G. Veeraraghavan (12/99-4/01); A. Santomarco (7/01-8/04); L. Sisti (4/05-10/06); L. Seib (6/07-present).

National Eye Institute

D. Everett (Project Officer).

Clinical Centers

University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Optometry: W. Marsh-Tootle (PI); K. Niemann (9/98-present); C. Baldwin (10/98-present); C. Dillard (10/09-present); K. Becker (7/99-3/03); J. Raley (9/97-4/99); A. Rawden (10/97-9/98); N. Harris (3/98-9/99); T. Mars (10/97-3/03); R. Rutstein (until 8/03).

New England College of Optometry: D. Kurtz (PI until 6/07); E. Weissberg (6/99-present; PI since 6/07); B. Moore (until 6/99); E. Harb (8/08-present); R. Owens; S. Martin (until 9/98); J. Bolden (10/98-9/03); J. Smith (1/01-8/08); D. Kern (8/05-8/08); S. Bittinger (8/08-4/11); B. Jaramillo (3/00-6/03); S. Hamlett (6/98-5/00); L. Vasilakos (2/02-12/05); S. Gladstone (6/04-3/07); C. Owens (6/06-9/09); P. Kowalski (until 6/01); J. Hazelwood (7/01-803).

University of Houston College of Optometry: R. Manny (PI); C. Crossnoe (until 5/03); K. Fern; S. Deatherage (until 3/07); C. Dudonis (until 1/07); S. Henry (until 8/98); J. McLeod (9/98-8/04; 2/07-5/08); M. Batres (8/04-1/06); J. Quiralte (1/98-7/05); G. Garza (8/05-1/07); G. Solis (3/07-8/11); A. Ketcham (6/07-9/11).

Pennsylvania College of Optometry: M. Scheiman (PI); K. Zinzer (until 4/04); K. Pollack (11/03-present); T. Lancaster (until 6/99); T. Elliott (until 8/01); M. Bernhardt (6/99-5/00); D. Ferrara (7/00-7/01); J. Miles (8/01-12/04); S. Wilkins (9/01-8/03); R. Wilkins (01/02-8/03); J. N. Smith (10/03-9/05); D. D’Antonio (2/05-5/08); L. Lear (5/06-1/08); S. Dang (1/08-2/10); C. Sporer ( 3/10-10/11); A. Grossman (8/01-11/03); M. Torres (7/97-6/00); H. Jones (8/00-7/01); M. Madigan-Carr (7/01-3/03); T. Sanogo (7/99-3/03); J. Bailey (until 8/03).

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

R. Hardy (Chair); A. Hillis; D. O. Mutti; R. Stone; Sr. C. Taylor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors have conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buch H, Vinding T, La Cour M, Appleyard M, Jensen GB, Nielsen NV. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment and blindness among 9980 Scandinavian adults: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saw SM, Gazzard G, Shih-Yen EC, Chua WH. Myopia and associated pathological complications. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2005;25:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitale S, Sperduto RD, Ferris FL., 3rd Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971–1972 and 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1632–1639. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi K, Ohno-Matsui K, Kojima A, Shimada N, Yasuzumi K, Yoshida T, Futagami S, Tokoro T, Mochizuki M. Fundus characteristics of high myopia in children. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:306–311. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi K, Ohno-Matsui K, Shimada N, Moriyama M, Kojima A, Hayashi W, Yasuzumi K, Nagaoka N, Saka N, Yoshida T, Tokoro T, Mochizuki M. Long-term pattern of progression of myopic maculopathy: a natural history study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1595–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.003. 611 e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldschmidt E, Fledelius HC. Clinical features in high myopia. A Danish cohort study of high myopia cases followed from age 14 to age 60. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:97–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. Optical Coherence Tomography of Ocular Diseases. 2nd ed. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sull AC, Vuong LN, Price LL, Srinivasan VJ, Gorczynska I, Fujimoto JG, Schuman JS, Duker JS. Comparison of spectral/Fourier domain optical coherence tomography instruments for assessment of normal macular thickness. Retina. 2010;30:235–245. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181bd2c3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girkin CA, McGwin G, Jr, Sinai MJ, Sekhar GC, Fingeret M, Wollstein G, Varma R, Greenfield D, Liebmann J, Araie M, Tomita G, Maeda N, Garway-Heath DF. Variation in optic nerve and macular structure with age and race with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2403–2408. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner-Schuman M, Dubis AM, Nordgren RN, Lei Y, Odell D, Chiao H, Weh E, Fischer W, Sulai Y, Dubra A, Carroll J. Race- and sex-related differences in retinal thickness and foveal pit morphology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:625–634. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashani AH, Zimmer-Galler IE, Shah SM, Dustin L, Do DV, Eliott D, Haller JA, Nguyen QD. Retinal thickness analysis by race, gender, and age using Stratus OCT. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girkin CA, Sample PA, Liebmann JM, Jain S, Bowd C, Becerra LM, Medeiros FA, Racette L, Dirkes KA, Weinreb RN, Zangwill LM. African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation Study (ADAGES): II. Ancestry differences in optic disc, retinal nerve fiber layer, and macular structure in healthy subjects. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:541–550. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Dairi MA, Asrani SG, Enyedi LB, Freedman SF. Optical coherence tomography in the eyes of normal children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:50–58. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grover S, Murthy RK, Brar VS, Chalam KV. Normative data for macular thickness by high-definition spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (spectralis) Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelty PJ, Payne JF, Trivedi RH, Kelty J, Bowie EM, Burger BM. Macular thickness assessment in healthy eyes based on ethnicity using Stratus OCT optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2668–2672. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song WK, Lee SC, Lee ES, Kim CY, Kim SS. Macular thickness variations with sex, age, and axial length in healthy subjects: a spectral domain-optical coherence tomography study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3913–3918. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan XR, Liang YB, Friedman DS, Sun LP, Wong TY, Tao QS, Bao L, Wang NL, Wang JJ. Normal macular thickness measurements using optical coherence tomography in healthy eyes of adult Chinese persons: the Handan Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1585–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo HD, Gazzard G, Fong A, Aung T, Hoh ST, Loon SC, Healey P, Tan DT, Wong TY, Saw SM. Myopia, axial length, and OCT characteristics of the macula in Singaporean children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2773–2781. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu PC, Chen YJ, Chen CH, Chen YH, Shin SJ, Yang HJ, Kuo HK. Assessment of macular retinal thickness and volume in normal eyes and highly myopic eyes with third-generation optical coherence tomography. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:551–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim MC, Hoh ST, Foster PJ, Lim TH, Chew SJ, Seah SK, Aung T. Use of optical coherence tomography to assess variations in macular retinal thickness in myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:974–978. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng SC, Lam CS, Yap MK. Retinal thickness in myopic and non-myopic eyes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2010;30:776–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2010.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyman L, Gwiazda J, Marsh-Tootle WL, Norton TT, Hussein M. The Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET): design and general baseline characteristics. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22:573–592. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gwiazda J, Hyman L, Hussein M, Everett D, Norton TT, Kurtz D, Leske MC, Manny R, Marsh-Tootle W, Scheiman M. A randomized clinical trial of progressive addition lenses versus single vision lenses on the progression of myopia in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1492–1500. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gwiazda JE, Hyman L, Norton TT, Hussein ME, Marsh-Tootle W, Manny R, Wang Y, Everett D. Accommodation and related risk factors associated with myopia progression and their interaction with treatment in COMET children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2143–2151. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gwiazda J, Marsh-Tootle W, Hyman L, Gwiazda J, Marsh-Tootle WL, Hyman L, Hussein M, Norton TT and the COMET group. Baseline refractive and ocular component measures of children enrolled in the correction of myopia evaluation trial (COMET) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:314–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadda SR, Keane PA, Ouyang Y, Updike JF, Walsh AC. Impact of scanning density on measurements from spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1071–1078. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odell D, Dubis AM, Lever JF, Stepien KE, Carroll J. Assessing errors inherent in OCT-derived macular thickness maps. J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:692574. doi: 10.1155/2011/692574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coletta NJ. Retinal thickness in myopia after adjustment for axial length variation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52 E-Abstract 3209. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwiazda J, Hyman L, Dong LM, Everett D, Norton T, Kurtz D, Manny R, Marsh-Tootle W, Scheimann M the COMET group. Factors associated with high myopia after 7 years of follow-up in the Correction of Myopia Evaluation Trial (COMET) Cohort. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14:230–237. doi: 10.1080/01658100701486459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam CS, Goh WS. The incidence of refractive errors among school children in Hong Kong and its relationship with the optical components. Clin Exp Optom. 1991;74:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fotedar R, Wang JJ, Burlutsky G, Morgan IG, Rose K, Wong TY, Mitchell P. Distribution of axial length and ocular biometry measured using partial coherence laser interferometry (IOL Master) in an older white population. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li XQ, Larsen M, Munch IC. Subfoveal choroidal thickness in relation to sex and axial length in 93 Danish university students. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:8438–8441. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donovan L, Sankaridurg P, Ho A, Naduvilath T, Smith EL, 3rd, Holden BA. Myopia progression rates in urban children wearing single-vision spectacles. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:27–32. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182357f79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith W, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Gender, oestrogen, hormone replacement and age-related macular degeneration: results from the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1997;25(Suppl. 1):S13–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1997.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sommer A. Glaucoma risk factors observed in the Baltimore Eye Survey. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1996;7:93–98. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199604000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennis AJ, Wu SY, Nemesure B, Hyman L, Schachat AP, Leske MC. Nine-year incidence of visual impairment in the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girkin CA, McGwin G, Jr, Xie A, Deleon-Ortega J. Differences in optic disc topography between black and white normal subjects. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]