Abstract

Purpose

Luteinizing hormone (LH) exerts its actions through its receptor (LHR), which is mainly expressed in theca cells and to a lesser extent in oocytes, granulosa and cumulus cells. The aim of the present study was the investigation of a possible correlation between LHR gene and LHR splice variants expression in cumulus cells and ovarian response as well as ART outcome.

Methods

Forty patients undergoing ICSI treatment for male factor infertility underwent a long luteal GnRH-agonist downregulation protocol with a fixed 5-day rLH pre-treatment prior to rFSH stimulation and samples of cumulus cells were collected on the day of egg collection. RNA extraction and cDNA preparation was followed by LHR gene expression investigation through real-time PCR. Furthermore, cumulus cells were investigated for the detection of LHR splice variants using reverse transcription PCR.

Results

Concerning LHR expression in cumulus cells, a statistically significant negative association was observed with the duration of ovarian stimulation (odds ratio = 0.23, p = 0.012). Interestingly, 6 over 7 women who fell pregnant expressed at least two specific types of LHR splice variants (735 bp, 621 bp), while only 1 out of 19 women that did not express any splice variant achieved a pregnancy.

Conclusions

Consequently, the present study provide a step towards a new role of LHR gene expression profiling as a biomarker in the prediction of ovarian response at least in terms of duration of stimulation and also a tentative role of LHR splice variants expression in the prediction of pregnancy success.

Keywords: LH receptor, Splice variants, Cumulus cells, Ovarian stimulation, ICSI, LH-priming

Introduction

Infertility can be defined as the failure to achieve a pregnancy within one year of regular unprotected intercourse. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment has been developed for infertile couples accomplishing an acceptable pregnancy rate compared to natural conception. Several patient characteristics are directly related to the response to ART treatment, which consequently dictates the need for reliable, personalized diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to optimize efficacy as well as safety outcomes. In this context, it is crucial for more genetic factors, which are involved in folliculogenesis and ovulation, to be examined whether or not they participate in the desirable outcome of an ART treatment [4].

Basically, genetic studies contribute towards our understanding of disease pathogenesis and help us to individualize the therapeutic approach. Patient tailored treatment is particularly critical in ART, as ovarian response to exogenous gonadotrophins varies widely and is often difficult to predict. Thus, genetic studies focus on genes or gene products (molecular biomarkers) that might serve in the assessment of patient’s fertility treatment prognosis in order to personalize the treatment accordingly. These studies rely on the identification and characterization of natural variants or polymorphisms in DNA sequence among individuals [23, 35].

It is widely recognized that bidirectional communication between the oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells determines the development and function of both cell types [25]. Based on this, recent studies have focused on cumulus cells gene expression, which is thought to indirectly reflect oocyte quality. Their findings have shed some light on novel biomarkers, which could be used as a non-invasive approach that preserves oocyte integrity for oocyte competence prediction [2, 14]).

Luteinizing hormone (LH) plays a fundamental role in folliculogenesis and ovulation, since it promotes final oocyte maturation and steroidogenesis in ovarian theca, granulosa and luteal cells. In line with the two cell-two gonadotropin theory, LH promotes androgen production by the theca cells, whereas FSH induces aromatase enzyme activity and thus the utility of androgens as a substrate for estrogen biosynthesis. In addition, the LH-related increase in intra-ovarian androgens has been postulated to enhance the sensitivity of granulosa cells to FSH [9]. This aspect was reinforced by recent evidence that, in patients down-regulated by GnRH analogues, a short-term pretreatment with recombinant LH (rLH), prior to recombinant FSH (rFSH) administration, increases the number of small antral follicles prior to FSH stimulation and the yield of normally fertilized (2PN) embryos [6]. Therefore, rLH pre-treatment may have a modest impact on subsequent ovarian responsiveness to FSH. However, only a subset of infertile women seem to benefit from the addition of LH to the stimulation protocol [20]. This could be possibly attributed to the differential luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) gene expression profile in these women.

In fact, many studies have focused on the identification of a threshold of serum LH level above which a favorable ART outcome exists. Levels of less than 1.5 IU/L do not support aromatase activity and estradiol production, whereas low pre-ovulatory levels of less than 3 IU/L in patients undergoing IVF are associated with impaired fertilization and increased early pregnancy loss [5, 38]. These discrepancies can be attributed to the use of different GnRH-agonist formulations, different LH assays, different gonadotrophin stimulation regimens and single point serum LH evaluation or serial LH assessments [16, 38]. However, differential LHR gene expression and/or LH splice variants expression in cumulus cells could be responsible for these inconclusive results.

Luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) belongs to the rhodopsin/β2-adrenergic receptor subfamily A of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) and has a large extracellular N-terminal ectodomain of less than 350 and up to 500 residues, which is involved in selective and high-affinity ligand binding. The hormone binds to the N-terminal ectodomain of the LHR instead of the transmembrane domains. Two highly conserved cysteine residues in the extracellular domain are thought to form a disulfide link, leading to a consequent packing and stabilization of a restricted number of conformations at the transmembrane helices of the receptor [1]. It was first found to be expressed in testicular and ovarian cells probably because it has an unusually high expression level in these organs. However, previous studies confirm that the LHR expression profile varies. Particularly, the LHR expression has been found to be expressed in the reproductive [34] and nervous system [19], prostate [33], adrenal gland [28], uterus [34], as well as in sperm [7] and ovum [30]. In addition, LHR expression has been monitored in some pathological conditions, concerning infertility and abnormal steroid hormone balance and in many cases, the expression is based on LHR mRNA detection [18, 37].

With regards to the ovary, LHR is mainly distributed in the theca cells. However, it has also been found in the oocyte and granulosa cells, as well as in cumulus cells surrounding mature oocytes in mice [10]. Besides, lower level of expression has also been detected in cumulus cells surrounding immature oocytes [10]. Normally, granulosa cells acquire LHR once the follicle reaches roughly 10 mm in size, i.e. during the mid follicular phase [13]. Interestingly, it has been shown that in ovulatory women with or without polycystic ovaries, granulosa cells responded to LH once follicles reached 9.5–10 mm, whereas in anovulatory patients with polycystic ovaries they responded to LH in follicles smaller than 4 mm [39]. LHR expression is further induced by FSH stimulation before oocyte maturation [10].

Previous investigations into the expression of the LHR in different species have described multiple splice variants generated by alternative splicing of the primary transcript. Minegishi and his co-workers detected two splice variants of the human luteal LHR [26]. Furthermore, Madhra and his co-workers described alternative splicing around the hinge region of the LHR in human corpora lutea and luteinized granulosa cells, detecting four splice variants of the LHR including the full length receptor, two of which contained premature stop codons [24].

In the present study, we examined LHR expression in cumulus cells of women undergoing a long luteal GnRH-agonist down-regulation protocol with rLH-priming for ICSI. Furthermore, we investigated the expression of LHR splice variants in cumulus cells of the same women. The primary endpoint was to investigate whether a correlation between LHR expression and demographic, hormonal or clinical characteristics exists. The secondary endpoint was to study if LHR splice variants expression is associated with ovarian response and ART outcome and thus it could serve as a biomarker in the evaluation of fertility treatment outcome prediction.

Materials and methods

Patient population

A total of 40 patients undergoing ICSI treatment [29] for male factor infertility were enrolled into a specific ART program. All women were pre-menopausal, 25–45 years of age with a normal hormonal profile according to WHO guidelines. Each of them had at least one unsuccessful ICSI treatment in the past, but had not received ovulation induction or other hormonal treatment within three months preceding recruitment.

Patients’ demographic characteristics (age, BMI, duration of infertility) were recorded before ovarian stimulation protocol. Gonadotrophin dose, duration of ovarian stimulation, number of follicles, oocytes and fertilized oocytes corresponding to each patient were monitored during the treatment cycle. It should be noted that day 2 hormonal profile (FSH, LH, PRL) had been measured within the previous six months.

Ovulation induction

Soon after the design of the study and before patient recruitment, the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Alexandra Hospital and an informed consent was provided by all participants.

All patients underwent a long luteal GnRH-agonist down-regulation protocol. A baseline ultrasound scan on day 21 of the preceding cycle was followed by intranasal Buserelin spray (Superfact; Hoechst, Frankfurt, Germany) initiation at a dose of 100 μg five times daily for 14 days. Pituitary down-regulation and subsequent ovarian suppression was confirmed with ultrasound scan (absence of ovarian cysts and endometrial proliferation) and low serum E2 levels (<40 pg/ml). If the above criteria were not met, down-regulation was extended for another week. As soon as pituitary desensitization had occurred, a fixed 5-day pre-treatment with 200 IU/day of rLH (Luveris; Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) followed by stimulation with 225 IU/day of rFSH (Gonal-F; Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) for five days and adjustment of the dose of rFSH thereafter was applied . Serum E2 levels were measured on day 5 and daily from day 8 of rFSH stimulation. Ultrasound scan was performed on a daily basis from day 9 and follicular growth along with endometrial thickness were recorded.

A dose of 10,000 IU of hCG (Pregnyl; N.V. Organon, Oss, Netherlands) for triggering final oocyte maturation was decided once the mean diameter of at least two follicles was >18 mm and serum E2 was rising. Oocytes were retrieved by transvaginal ultrasound-guided ovarian puncture 35–36 h post hCG injection. Oocyte maturation was assessed under the microscope following stripping of the cumulus-oocyte complexes and mature oocytes (metaphase II) were used for ICSI. On day 3, three embryos were transferred back to the uterus. Luteal phase support was provided with vaginal progesterone pessaries started on the day of oocyte retrieval as well as 2,500 IU of hCG given on the days of embryo transfer and four days later. Pregnancy was confirmed with serum hCG levels determined 14 days following egg collection, whereas clinical pregnancy was defined as a gestational sac with positive fetal heart activity seen on transvaginal ultrasound scan two weeks later.

RNA extraction and cDNA preparation

For the determination of LHR mRNA expression cumulus cells were collected on the day of ooocyte retrieval. In particular, the cells were segregated from cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) through the process of stripping using hyaluronidase. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as previously described [31].

Aliquots (10 μl) of total RNA extracted were reverse-transcribed using 8 μl dNTP mix, 10 μl nuclease free water, 4 μl oligo dT Primer, 4 μl RT buffer (Ambion, Austin, Tx, USA), 2 μl ribonuclease inhibitor and 2 μl M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The reactions were carried out in Mastercycler (Eppendorf) with the following conditions: 80°C for 3 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 92°C for 10 min. The resulting cDNAs were stored at −20°C.

Real-time PCR

The expression of human LH receptor in cumulus cells was examined by real-time PCR using the primers and probes set particularly designed for this study. The oligonucleotide primers for LHR gene were synthesized by TIB MOLBIOL and their sequences were as follows: LCGRx9 S:5′-CTGCCGAGCTATGGCCTAG-3′ and LCGRx9,10 A:5′-ATTCTGTTCTTTTGTTGGCAAGTT-3′. The sequences of the probes also synthesized by TIB MOLBIOL were as follows: LHCGR-FL:5′-AACATTTGTCAATCTCCTGGAGGCC—FL and LHCGR-LC:5′-LC640-CGTTGACTTACCCCAGCCACTGC—PH. The specific primers and probes were used at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl in each reaction. Real-time PCR was performed on LightCycler 480 II (Roche) with the following parameters: one cycle at 95°C for 10 min for pre-incubation and 40 cycles for amplification [95°C for 10 s, 57°C for 20 s, 72°C for 10 s]. All PCR mixtures contained 5 μl cDNA, 2 μl master mix of LightCycler 480 Genotyping Master (Roche), 4 μl primer mix of 16x hu G6PD (TIB MOLBIOL), 2.4 μl MgCl2 of LightCycler 480 Genotyping Master (Roche), 0.5 μl for each primer and 0.2 μl for each probe.

Expression of LHR gene was normalized to G6PDH expression (LightMix Kit human G6PD, TIB MOLBIOL). In particular, Cp-value was used, which represents the time-point at which the fluorescence of the sample rises above the background fluorescence during the real-time PCR process and the results were converted to ratios based on the reference of Müller and his co-workers [27] using G6PDH as gene reporter in order to have comparable results. LHR expression was categorized into three groups based on the quartiles of the overall distribution. Hence, low expression was defined up to 25th percentile (<=0.0057), medium expression from 25th up to 75th percentile (0.0058–0.150) and high expression from 75th percentile and up (>0.150).

Detection of splice variants with RT-PCR

cDNA was also used for the detection of splice variants of LHR gene through Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR). The primers were obtained from TIB MOLBIOL, Germany and the sequence was based on previous studies [24]. Two μl of cDNA were added in a 25 μl total volume containing 10X Reaction buffer, 1.5 μl MgCl2, 1 μl of each primer, 1 μl dNTPs and 0.3 μl Taq polymerase. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 s at 95°C, 1 min at 62°C and 90 s at 72°C. The above steps were repeated for 30 times with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 5 min and a final elongation step of 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were electrophoresed in a 2% agarose gel and visualized under U.V.

Statistical analysis

The results of the present study were subjected to statistical analysis. Due to the deviation from normality we applied non-paramentric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests in order to evaluate the univariate association of demographic and biochemical factors, as well as factors included in the ovarian stimulation profile of each patient and LHR gene expression in cumulus cells. In addition, we applied multiple logistic regression to investigate possible determinants of LHR gene expression. It should be noted that statistical significance was defined at the level of 5% (p < 0.05).

Results

LHR expression in cumulus cells

LHR expression in cumulus cells measured through quantitative PCR (real time PCR) was low in 9 women, medium in 19 women and high in 12 women out of the 40 women that consisted our study population. As a result, medium to high expression of LHR gene in cumulus cells was observed in 6 out of 7 women who fell pregnant, since 4 out of 7 women with pregnancy presented high LHR gene expression, two women had medium expression and one woman low expression. Statistical analysis was conducted to study possible correlations between LHR expression and demographic, hormonal and clinical parameters (Table 1). Interestingly, a statistically significant difference was detected between the LHR gene expression in the three groups of women and the duration of ovarian stimulation (p = 0.044). Women with high expression of LHR gene in cumulus cells required a shorter ovarian stimulation period compared to women with low and medium expression (median = 10 vs 11 days). The above finding was reinforced by multiple logistic regression analysis, when we combined women with low and medium LHR expression and compared them with those that had high expression. In fact, a statistically significant inverse association was observed between days of stimulation and LHR gene expression in cumulus cells (OR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.08–0.73, p = 0.012), as presented in Table 2. Furthermore, although non-statistically significant, a trend towards a negative association was found between LHR expression and woman’s age (OR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.14–1.35, p = 0.148). Finally, a trend towards a favorable correlation was seen between LHR expression and ART outcome in terms of success of pregnancy, as 4 out of 12 women with high expression (33.3%) fell pregnant contrary to 2 out of 19 with medium (10.52%) and 1 out of 9 with low expression (11.11%). However, this finding did not reach statistical significance.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic, hormonal and clinical parameters by LHR expression in cumulus cells (Kruskal-Wallis test) and pregnancy rate corresponded to each expression level

| LHR expression (cumulus cells) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 9) | Medium (n = 19) | High (n = 12) | p-value | |

| Median ± SD | Median ± SD | Median ± SD | ||

| Age (years) | 33.0 ± 2.4 | 35.0 ± 4.9 | 32.0 ± 4.5 | 0.208 |

| BMI | 22 ± 4.2 | 24.2 ± 3.3 | 22.6 ± 6.6 | 0.510 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 7.1 ± 1.8 | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 7.0 ±3.0 | 0.892 |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 5.9 ± 2.2 | 0.728 |

| PRL (ng/ml) | 17.1 ± 3.5 | 12.9 ± 7.6 | 17.2 ± 8.0 | 0.195 |

| Stimulation dose (IU) | 2200 ± 337 | 2613 ± 1545 | 2400 ± 723 | 0.685 |

| Number of follicles | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 10.0 ± 2.0 | 10.0 ± 2.0 | 0.262 |

| Number of oocytes | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 0.886 |

| Number of fertilized oocytes | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | 0.851 |

| Infertility (years) | 3.0 ± 3.0 | 5.0 ± 4.0 | 5.0 ± 3.0 | 0.262 |

| Ovarian stimulation (days) | 11.0 ± 1.0 | 11.0 ± 4.0 | 10.0 ± 1.0 | 0.044 |

| Number of Pregnancies | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression with the derived odds ratios (ORs) for 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between LHR gene expression in cumulus cells and days of stimulation, as well as age

| LHR expression low/medium vs high (cumulus cells) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Ovarian stimulation (days) | 0.23 (0.08–0.73) | 0.012 |

| Age (years) | 0.43 (0.14–1.35) | 0.148 |

Splice variants of LHR gene in cumulus cells

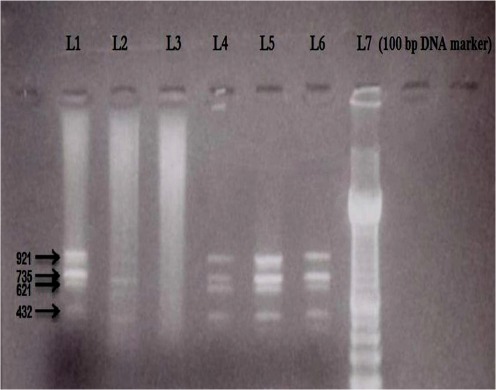

Apart from the expression of LHR, splice variants of this gene were also investigated in cumulus cells, in order to conclude whether or not the number and/or the type of splice variants expressed in those women are related to ART outcome in terms of pregnancy. Specifically, 4 different types of splice variants of LHR gene including the full length receptor were investigated having the following sizes: 921, 735, 621 and 432 bp (the product 921 bp represents the full length receptor). Figure 1 shows indicatively the types of splice variants of LHR gene expressed in cumulus cells after performing electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel. According to the results of electrophoresis, 17 over 40 women expressed all four types of splice variants of LHR gene, one woman the three types, three women the two types, while in 19 over 40 women none of the splice variants studied was detected. Nevertheless, none of the 40 the patients expressed a single splice variant. Table 3 demonstrates the combinations of splice variants of LHR gene detected in women that succeeded a pregnancy. As presented, 6 out of 7 women that achieved a pregnancy expressed at least two specific types of splice variants (735 bp, 621 bp). It should be mentioned that only 1 out of 19 women that did not express any of the four types of splice variants through RT-PCR fell pregnant, even though in that patient the expression of LHR was detected in cumulus cells through real-time PCR.

Fig. 1.

Representative electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel showing the expression of splice variants of LHR gene in cumulus cells. The four different types of splice variants are presented indicatively in Lane 1 (921, 735, 621 and 432 bp). A 100 bp DNA marker was used for size analysis (L7)

Table 3.

Combinations of splice variants of LHR gene detected in women that succeeded a pregnancy

| Splice variants combination (bp) | 921-735-621-432 | 735-621 | No splice variant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with pregnancy | 3 | 3 | 1 |

Discussion

This study was designed to determine LHR gene expression as well as LHR splice variants expression in cumulus cells of women who underwent a course of rLH-priming in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for ICSI in order to investigate the potential role of LHR expression profile in the ART processes.

Although extensively studied, the addition of LH activity in the form of rLH, hMG or hCG in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is still considered a matter of debate. Several studies have drawn contradictory conclusions regarding the ideal form and amount of LH activity, the optimal time frame to be given (pre-treatment, early, late follicular phase or thoughout the follicular phase) and the ideal female population in terms of age and prognosis to fertility treatment in general. The differences in GnRH-agonist formulations, LH assays, gonadotrophin stimulation regimens and single point serum LH evaluation or serial LH assessments have been charged for these discordancies. However, differences in the expression profile of LHR and its splice variants between women who seem to benefit or not from LH activity in COH cannot be excluded.

Recent evidence in non-primates has shown that LH may act by increasing intra-ovarian androgens, which in turn promote FSH responsive granulosa cell function [9]. We opted a fixed 5-day course of 200 IU rLH daily dose for pre-treatment and not a 7-day one of 300 IU used by others [6] because we designed to start rLH as soon as pituitary desensitization had occurred prior and not concurrently with rFSH administration. We thought that a higher dose would probably compromise follicular potential as LHR are present only on theca and not granulosa cells by that time.

The acknowledgement of bidirectional communication between the human oocyte and the surrounding cumulus cells have recently led to the investigation of cumulus cell gene expression in an effort to unfold the microenvironment the oocyte is exposed during the final stages of maturation. Although such studies are still in their infancy, new insights from the cumulus cell transcriptome and/or the proteins it produces might help in the assessment of oocyte quality. In this study, we decided to isolate cumulus cells by stripping COCs with the application of hyaluronidase according to our routine practice. Although a potential effect of the enzymatic method in cumulus cell gene expression profile cannot be ruled out, we thought that mechanical isolation of cumulus cells before ICSI could jeopardise the success of our patients’ fertility treatment rendering our strategy unethical. Nevertheless, hyaluronidase has been used by other researchers in cumulus cell gene expression studies even in non-human mammals (cows) [2, 3].

A study by Haouzi and his co-workers found LHR expression in cumulus cells of all the patients studied without significant differences in LHR gene expression profile between GnRH agonist long or antagonist protocols and between hMG or rFSH treatments [12]. However, others reported a lower LHR gene expression in floating granulosa cells in patients undergoing a long GnRH agonist protocol with hMG in comparison to rFSH [11]. Our results are in line with the findings of Haouzi and his co-workers, in that LHR gene expression was detected in cumulus cells of all the patients, who underwent an ICSI protocol. Of note, these women underwent a specific ART procedure with rLH pre-treatment prior to rFSH stimulation. Notably, the vast majority of the subset of women that succeeded a pregnancy (6 out of 7 women) showed medium to high expression and only one woman had low expression. It should be mentioned that a statistically significant negative association was observed between days of stimulation and LHR gene expression in cumulus cells (OR = 0.23, p = 0.012), suggesting a favorable role of LHR in ovarian response, since women with high LHR mRNA levels needed a shorter period of stimulation. However, in our population, rLH pre-treatment anteceded COH protocol and LH activity was omitted during rFSH stimulation period. In case that future larger scale studies validate our results, the potential correlation of LHR expression with the duration of stimulation as well as other demographic, hormonal and clinical parameters of the ART process in various LH activity schemes could be investigated.

Another genetic approach of the correlation between LHR expression and ART procedure is through the detection of splice variants. Various studies have been published concerning LHR splice variants, which play a significant role in LHR functions. In particular, alternative splicing appears to be associated with cycle-dependent regulation of LHR mRNA levels in human endometrium [21] and receptor down-regulation in rat corpora lutea [17]. In addition, the different types of splice variants have also been shown to take place in pathophysiological conditions, such as endometrial carcinomas, which is related to increased levels of spliced LHR transcripts [22] or in human ovarian [31, 36] and breast epithelial cell tumors [15], in which alternative splicing is shown to be altered or ceased when compared to normal cells.

Madhra and his co-workers described four different types of splice variants including the full-length LHR, which we also detected in cumulus cells. In the same study, they tried to detect a splice variant lacking exon 10, but no patient showed such a deletion. In our study no patient showed an exon 10 deletion confirming the hypothesis that this region is probably highly conserved. Given that LHR gene expression in cumulus cells was found through real-time PCR in our study population, the seemingly contradictory result of 19 women expressing none of the LHR splice variants studied, including the full length receptor, can be probably attributed to the lower sensitivity of RT-PCR technique compared to real-time PCR. It is known that the latter has a sensitivity of detection of 10 copies. Such a low number of copies cannot be identified with RT-PCR. Of note, the presence of cDNA was verified in all samples using G6PD as a reporter gene [8], even in samples where LHR splice variants were not detected through RT-PCR.

Our results show a tentative favorable outcome for women with at least two specific splice variants (735 bp, 621 bp), which could lead to the hypothesis that this combination in women pre-treated with rLH might contribute a better microenvironment to the developing oocyte leading to a superior oocyte quality and competence. Another potential assumption could be the production of a different but functional LHR protein isoform by alternative splicing, which may act as a receptor of hCG in maternal recognition of pregnancy.

It is also remarkable that women in which none of the four types of splices variants was detected through RT-PCR, even if they had an expression of LHR gene in cumulus cells through real-time PCR, did not achieve pregnancy. In addition, only 1 out of 19 women without detectable splice variants resulted in pregnancy. This could imply that among other factors, a threshold level of LHR gene expression favors pregnancy attainment and maybe this level lies within the detection range of RT-PCR. Interestingly, the presence of a single splice variant was not detected in any of the 40 women. Further investigation with molecular and protein techniques is needed to further assess this finding. However, the sequence of LHR amplified by real-time PCR is probably common to all samples, but deletions in exons upstream and downstream correspond to a truncated and non-functional protein.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed LHR gene expression in cumulus cells in patients undergoing rLH-priming in controlled ovarian stimulation for ICSI. Obviously, alternative splicing of LHR gene affects the structure and thus the function of LHR in the ovary. Moreover, different expression patterns of LHR gene possibly participate in the response to ovarian stimulation, with an expression threshold related to the favorable outcome. Provided that these findings are confirmed and validated by other researchers in future studies, optimization and standardization of LHR gene expression techniques in cumulus cells removed from COCs before ICSI, might offer a non-invasive method that preserves oocyte integrity in the selection of the most competent gametes for fertilization. This could probably result in improved fertilization, implantation and pregnancy rates. Meantime, studies on patients undergoing COH through different LH activity schemes and also conventional protocols lacking rLH-priming effect could be conducted to clarify whether LHR gene and LHR splice variants expression profile in cumulus cells depends on rLH pre-treatment and to which extent, in order to tailor COH protocol to the individual patient. Although our results are awaiting confirmation, they provide a step towards a new role of LHR gene expression profiling in the prediction of ovarian response at least in terms of duration of stimulation and also a tentative role of LHR splice variants expression in the prediction of pregnancy success.

Footnotes

Capsule LH Receptor gene and LH Receptor splice variants expression predict the outcome of ART cycles

References

- 1.Apaja P. Luteinizing hormone receptor-Expression and post-translational regulation of the rat receptor and its ectodomain splice variant. Oulun Yliopisto 2005; ISBN 951-42-7929-8. (http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9514279298/isbn9514279298.pdf)

- 2.Assidi M, Dieleman SJ, Sirard MA. Cumulus cell gene expression following the LH surge in bovine preovulatory follicles: potential early markers of oocyte competence. Reproduction. 2010;140(6):835–52. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettegowda A, Patel OV, Lee KB, Park KE, Salem M, Yao J, Ireland JJ, Smith GW. Identification of novel bovine cumulus cell molecular markers predictive of oocyte competence: functional and diagnostic implications. Biol Reprod. 2008;79(2):301–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.067223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devroey P, Fauser BCJM, Diedrich K. Approaches to improve the diagnosis and management of infertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(4):391–408. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drakakis P, Loutradis D, Kallianidis K, Liapi A, Milingos S, Makrigiannakis A, Dionyssiou-Asteriou A, Michalas S. Small doses of LH activity are needed early in ovarian stimulation for better quality oocytes in IVF-ET. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durnerin CI, Erb K, Fleming R, Hillier H, Hillier SG, Howles CM, Hugues JN, Lass A, Lyall H, Rasmussen P. Effects of recombinant LH treatment on folliculogenesis and responsiveness to FSH stimulation. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(2):421–426. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eblen A, Bao S, Lei ZM, Nakajima ST, Rao CV. The presence of functional luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptors in human sperm. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(6):2643–2248. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.6.2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emig M, Saussele S, Wittor H, Weisser A, Reiter A, Willer A, Berger U, Hehlmann R, Cross NC, Hochhaus A. Accurate and rapid analysis of residual disease in patients with CML using specific fluorescent hybridization probes for real time quantitative RT-PCR. Leukemia. 1999;13(11):1825–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming R, Durnerin IC, Erb K, Hillier SG, Hugues JN, Lyall H, Rasmussen PE, Thong J, Traynor I, Westergaard LG. Pre-treatment with rhLH: respective effects on antral follicular count and ovarian response to rhFSH. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(Supp I):i54. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu M, Chen X, Yan J, Lei L, Jin S, Yang J, Song X, Zhang M, Xia G. Luteinizing hormone receptors expression in cumulus cells closely related to mouse oocyte meiotic maturation. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1804–1813. doi: 10.2741/2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grøndahl ML, Borup R, Lee YB, Myrhøj V, Meinertz H, Sørensen S. Differences in gene expression of granulosa cells from women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with either recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone or highly purified human menopausal gonadotropin. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(5):1820–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haouzi D, Assou S, Mahmoud K, Hedon B, Vos J, Dewailly D, Hamamah S. LH/hCGR gene expression in human cumulus cells is linked to the expression of the extracellular matrix modifying gene TNFAIP6 and to serum estradiol levels on day of hCG administration. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(11):2868–2878. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillier SG, Whitelaw PF, Smyth CD. Follicular oestrogen synthesis: the ‘two-cell, two-gonadotrophin’ model revisited. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;100(1–2):51–54. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Z, Wells D. The human oocyte and cumulus cells relationship: new insights from the cumulus cell transcriptome. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16(10):715–25. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Russo IH, Russo J. Alternately spliced luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin receptor mRNA in human breast epithelial cells. Int J Oncol. 2002;20(4):735–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolibianakis EM, Collins J, Tarlatzis B, Papanikolaou E, Devroey P. Are endogenous LH levels during ovarian stimulation for IVF using GnRH analogues associated with the probability of ongoing pregnancy? A systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(1):3–12. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakkakorpi JT, Pietilä EM, Aatsinki JT, Rajaniemi HJ. Human chorionic gonadotrophin (CG)-induced down-regulation of the rat luteal LH/CG receptor results in part from the downregulation of its synthesis, involving increased alternative processing of the primary transcript. J Mol Endocrinol. 1993;10(2):153–162. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0100153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latronico AC, Segaloff DL. Naturally occurring mutations of the luteinizing-hormone receptor: lessons learned about reproductive physiology and G protein-coupled receptors. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(4):949–958. doi: 10.1086/302602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei ZM, Rao CV, Kornyei JL, Licht P, Hiatt ES. Novel expression of human chorionic gonadotropin/luteinizing hormone receptor gene in brain. Endocrinology. 1993;132(5):2262–2270. doi: 10.1210/en.132.5.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lévy DP, Navarro JM, Schattman GL, Davis OK, Rosenwaks Z. The role of LH in ovarian stimulation: exogenous LH: let’s design the future. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(11):2258–2265. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.11.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Licht P, Wolff M, Berkholz A, Wildt L. Evidence for cycle-dependent expression of full-length human chorionic gonadotropin/luteinizing hormone receptor mRNA in human endometrium and decidua. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(1):718–723. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J, Lei ZM, Lojun S, Rao CV, Satyaswaroop PG, Day TG. Increased expression of luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin receptor gene in human endometrial carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(5):1483–1491. doi: 10.1210/jc.79.5.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loutradis D, Patsoula E, Minas V, Koussidis GA, Antsaklis A, Michalas S, Makrigiannakis A. FSH receptor gene polymorphisms have a role for different ovarian response to stimulation in patients entering IVF/ICSI-ET programs. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006;23(4):177–84. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-9015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhra M, Gay E, Fraser HM, Duncan WC. Alternative splicing of the human luteal LH receptor during luteolysis and maternal recognition of pregnancy. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(8):599–603. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matzuk MM, Burns KH, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ. Intercellular communication in the mammalian ovary: oocytes carry the conversation. Science. 2002;21;296(5576):2178–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1071965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minegishi T, Tano M, Abe Y, Nakamura K, Ibuki Y, Miyamoto K. Expression of luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotrophin (LH/HCG) receptor mRNA in the human ovary. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3(2):101–107. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller MC, Saglio G, Lin F, Pfeifer H, Press RD, Tubbs RR, Paschka P, Gottardi E, O’Brien SG, Ottmann OG, Stockinger H, Wieczorek L, Merx K, König H, Schwindel U, Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A. An international study to standardize the detection and quantitation of BCR-ABL transcripts from stabilized peripheral blood preparations by quantitative RT-PCR. Haematologica. 2007;92:970–973. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pabon JE, Li X, Lei ZM, Sanfilippo JS, Yussman MA, Rao CV. Novel presence of luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptors in human adrenal glands. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(6):2397–2400. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.6.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palermo G, Joris H, Devroey P, Steirteghem AC. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet. 1992;340:17–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patsoula E, Loutradis D, Drakakis P, Kallianidis K, Bletsa R, Michalas S. Expression of mRNA for the LH and FSH receptors in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Reproduction. 2001;121(3):455–461. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patsoula E, Loutradis D, Drakakis P, Michalas L, Bletsa R, Michalas S. Messenger RNA expression for the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor and luteinizing hormone receptor in human oocytes and preimplantation-stage embryos. Fertility Sterility. 2003;79(5):1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Reinholz MM, Zschunke MA, Roche PC. Loss of alternately spliced messenger RNA of the luteinizing hormone receptor and stability of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor messenger RNA in granulosa cell tumors of the human ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79(2):264–271. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiter E, McNamara M, Closset J, Hennen G. Expression and functionality of luteinizing hormone/chorionic gonadotropin receptor in the rat prostate. Endocrinology. 1995;136(3):917–923. doi: 10.1210/en.136.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reshef E, Lei ZM, Rao CV, Pridham DD, Chegini N, Luborsky JL. The presence of gonadotropin receptors in nonpregnant human uterus, human placenta, fetal membranes, and decidua. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70(2):421–430. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-2-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simoni M, Nieschlag E, Gromoll J. Isoforms and single nucleotide polymorphisms of the FSH receptor gene: implications for human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8(5):413–21. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinmeyer C, Berkholz A, Gebauer G, Jager W. The expression of hCG receptor mRNA in four human ovarian cancer cell lines varies considerably under different experimental conditions. Tumour Biol. 2003;24(1):13–22. doi: 10.1159/000070656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Themmen APN, Huhtaniemi IT. Mutations of gonadotropins and gonadotropin receptors: elucidating the physiology and pathophysiology of pituitary-gonadal function. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(5):551–583. doi: 10.1210/er.21.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westergaard LG, Laursen SB, Andersen CY. Increased risk of early pregnancy loss by profound suppression of luteinizing hormone during ovarian stimulation in normogonadotrophic women undergoing assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(5):1003–1008. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.5.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willis DS, Watson H, Mason HD, Galea R, Brincat M, Franks S. Premature response to luteinizing hormone of granulosa cells from anovulatory women with polycystic ovary syndrome: relevance to mechanism of anovulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(11):3984–3991. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.11.3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]