Abstract

Background

Posterosuperior glenoid impingement (PSGI) is the repetitive impaction of the supraspinatus tendon insertion on the posterosuperior glenoid rim in abduction and external rotation. While we presume the pain is mainly caused by mechanical impingement, this explanation is controversial. If nonoperative treatment fails, arthroscopic débridement of tendinous and labral lesions has been proposed but reportedly does not allow a high rate of return to sports. In 1996, we proposed adding abrasion of the bony posterior rim, or glenoidplasty.

Description of Technique

After arthroscopic assessment of internal impingement in abduction-extension-external rotation, extensive posterior labral and partial tendinous tear débridement is performed. Glenoidplasty involves recognition of a posterior glenoid spur and when present subsequent abrasion with a motorized burr.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 27 throwing athletes treated between 1996 and 2008. Age averaged 27 years. CT arthrogram showed bony changes on the posterior glenoid rim in 21 shoulders. We evaluated 26 of the 27 patients at a minimum followup of 19 months (mean, 47 months; range, 19–123 months).

Results

Eighteen of the 26 patients resumed their former sport level. Six improved but had to change to an inferior sport level or another sport. Two patients did not improve after the procedure, one of whom changed sport practice. There were no complications or posterior instability. In the 15 patients who had radiographs at followup times from 20 to 87 months, we observed no arthritis or osteophyte.

Conclusions

Comparison with an earlier series of soft tissue débridement shows glenoidplasty improves the likelihood of resuming a former sport level in patients with PSGI.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Posterosuperior glenoid impingement (PSGI) was described in 1991 by Walch et al. [23] as a mechanism of shoulder pain in throwing athletes. The articular side of the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon impinges against the posterosuperior rim glenoid in the combined movement of abduction and extreme external rotation (Fig. 1). In this position, both elements are in contact, as demonstrated anatomically by Jobe [8]. The contact is probably physiologic in a large proportion of normal population. After thousands of high-intensity cycles, as during throwing sports activity, the impingement may create pathologic changes. These include various grades of tendon injury (tendinopathy, articular partial tear, complete tear) and various types of posterior glenoid rim injury (labral lesion, marginal chondral lesion, glenoid cyst, glenoid spur).

Fig. 1.

A diagram illustrates PSGI, which is an internal impingement of the articular side of the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon against the posterosuperior rim glenoid in the combined movement of abduction and extreme external rotation.

The cause of the pain is controversial [5, 9, 14, 18]. Kvitne and Jobe [9] suggested the pain is a consequence of a subtle anterior instability while Burkhart et al. [5] believed the pain is the result of hypertwisting of the rotator cuff fibers with hyperexternal rotation. We suspect mechanical impingement of the tendinous cuff insertion on the glenoid rim creates tendon lesions, which are the cause of the pain. Based on this presumption, the standard arthroscopic procedure is to débride tendinous and labral lesions. However, the literature suggests many of these motivated athletes do not return to their regular sports (Table 1) [13, 18, 20, 22].

Table 1.

Comparison of return to sports between our study and the literature

In 1996, we observed large posterior glenoid spurs in two PSGIs in throwing athletes. These were distinct from typical Bennett lesions as described by several authors [3, 12, 16] and we presumed they would cause painful abutment on the spur (Fig. 2). We therefore decided to add an abrasion of the spur to the current arthroscopic technique of soft tissue débridement. While we observed no complications after abrading the excessive bone, it remained unclear whether this procedure uniformly relieves pain or allows patients to return to their original sport.

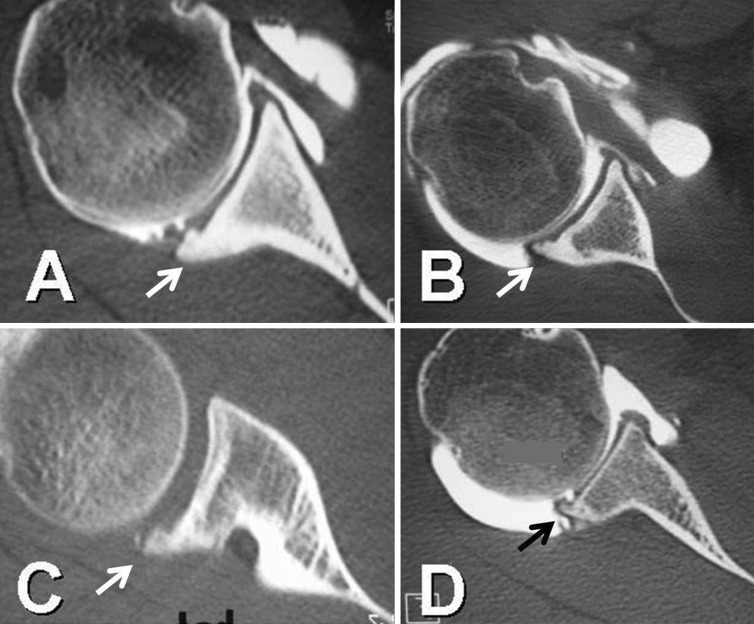

Fig. 2A–D.

CT arthrograms show four different types of bony spur on the posterior glenoid rim indicated by arrows: (A) densification and hypertrophy of glenoid rim, (B) spiked spur, (C) overhanging spur, and (D) spiked spur.

Our goals therefore are to (1) describe this procedure, (2) determine the ability to resume sport with this undescribed procedure in a retrospective study of a consecutive series of 27 patients, and (3) assess complications or detrimental consequences after the procedure.

Surgical Technique

The indications for arthroscopic treatment when posterior glenoid impingement was suspected were failure of nonoperative treatment and specific rehabilitation. At the beginning of our experience, the indications for posterior glenoidplasty were (1) arthroscopic signs of posterior glenoid impingement and (2) posterior glenoid spur detected on preoperative radiograph or CT scan. Encouraged by the improvement of pain during sport practice comparatively with our prior technique [20], we extended the indications in six patients despite the absence of a glenoid spur. We did not recommend the procedure in patients with (1) functional improvement after nonoperative treatment and (2) patients unmotivated to continue sports. Nonoperative treatment with specific rehabilitation was tried for every patient for a minimum of 3 months before the decision to perform arthroscopy was made.

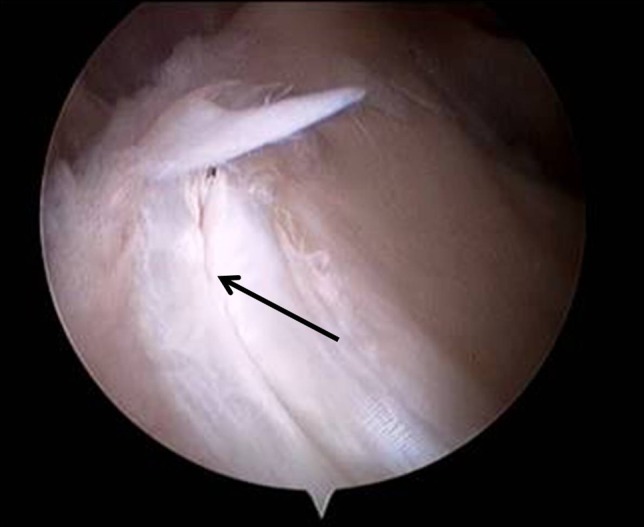

All patients had general anesthesia. The position was lateral decubitus in 11 patients and beach chair in 16 patients. The procedure was standardized as follows. First, we explored the glenohumeral joint through the posterior portal; the supraspinatus/infraspinatus tendon insertion was examined for partial tear (Fig. 3). In this cohort, all patients had lesions of the posterior labrum and partial tear of the tendon insertion, but five were detected only after positioning the arm in abduction-extension-external rotation (the critical position). On the glenoid side, the posterior labrum was pathologic (delamination or flap) in all patients (Fig. 4). A posterior spur was easily detected and palpated in 17 of 27 patients. The instrument portal was anterior-superior, just anterior to the acromioclavicular joint. Accurate position and direction were checked with a needle before portal placement to ensure the ability to reach the posterosuperior rim up to the glenoid equator. Second, the arm was placed in the critical position (abduction-extension-external rotation). This maneuver was essential to confirm the diagnosis, demonstrating the tendon lesion impinged on the glenoid rim. Third, we performed extensive débridement of the posterior labral with a motorized shaver, starting superiorly 15–20 mm posterior to the biceps insertion, removing all the pathologic tissue and precluding any labral reinsertion. The débridement was often continued into the posteroinferior part (seven o’clock position on a right shoulder). When present, the posterior glenoid spur was easily detected and palpable at this point. Fourth, the glenoidplasty was performed with the motorized burr, removing the spur to obtain a smooth posterior glenoid rim (Fig. 5). The spur was frequently located a little medial to the rim and could extend below the glenoid equator. Thus, an additional instrumental portal (Neviaser portal or posterolateral portal) was required to more easily reach the posteroinferior glenoid rim. Alternatively, the posterior scope and anterior instruments could be exchanged to facilitate reaming. If there was no spur or no remodeling of posterior glenoid rim (six patients in our series), we completed the soft tissue débridement by reaming the glenoid rim to obtain a smooth posterior angle. The arm was then positioned in the critical position to ensure absence of residual impingement.

Fig. 3.

An arthroscopic view of the right shoulder shows an articular partial tear of the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon (arrow) with a tendinous flap, just posterior to the biceps.

Fig. 4.

An arthroscopic view shows posterior labrum delamination (arrow).

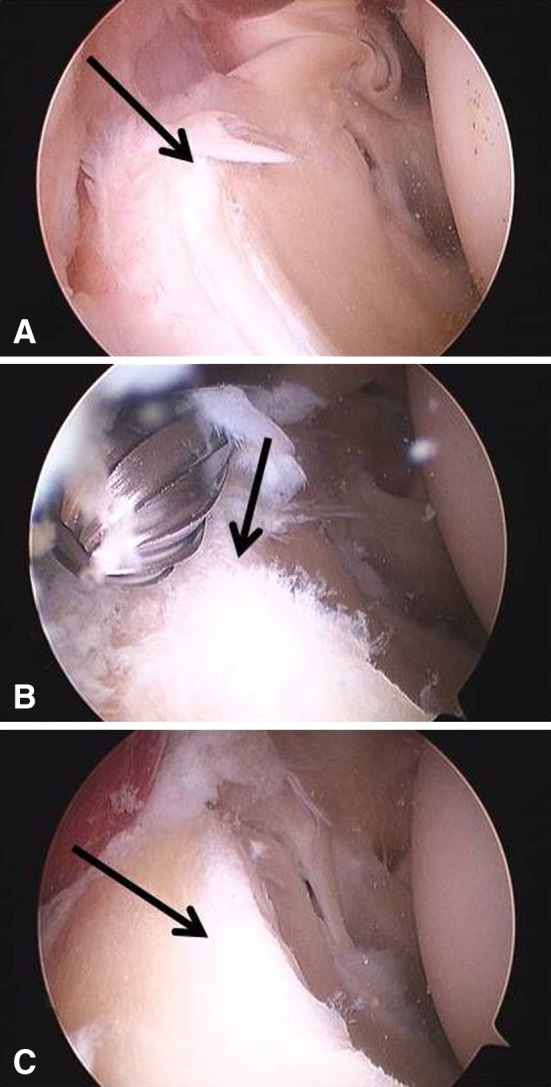

Fig. 5A–C.

An arthroscopic sequence of posterior glenoidplasty is shown: (A) flap and delamination of the labrum (arrow) are shown before the procedure; (B) after extensive labral débridement, posterior spur and glenoid rim are abraded with a burr (arrow); and (C) after the procedure, the glenoid rim is flat and smooth (arrow).

Passive rehabilitation began the day after surgery and patients were encouraged to raise their arm with the other hand in lying position, as far as possible every day, with a self-rehabilitation program. The operated arm was protected in a sling for 10–15 days. After 15 days, and only if symmetrical passive anterior elevation was obtained, active anterior elevation and use of the arm in daily life were allowed. Progressive sport training was allowed after 3 months.

Patients and Methods

Between 1996 and 2008, we performed arthroscopic posterior glenoidplasty in 27 patients (27 dominant shoulders) to treat PSGI. The age averaged 27 years (range, 18–39 years). All patients were athletes involved in competitive sports (handball 14, volleyball seven, tennis three, javelin one, swimming one, baseball one). Nineteen athletes performed in regional leagues and eight in national leagues.

Pain in abduction-external rotation was the major symptom in all patients. Fifteen patients had pain only during sports, while 12 also reported pain in activities of daily living. No patients had restriction of motion. Only two patients had weakness on supraspinatus testing. Constant-Murley scores were not substantially reduced in this athletic population. We analyzed the posterior glenoid rim by radiography and CT arthrography. Seventeen shoulders showed bone spurs or hypertrophy (Fig. 2), four shoulders showed remodeling, and six shoulders appeared normal. Partial tear of the articular side of the supraspinatus tendon was present in 13 shoulders on CT arthrogram (Fig. 6).

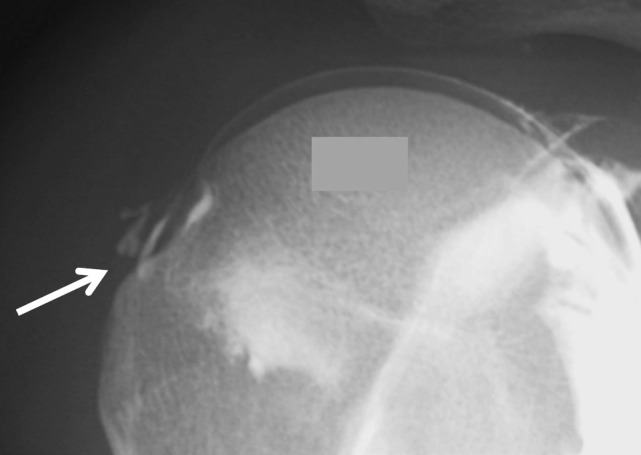

Fig. 6.

A partial tear of the articular side of the supraspinatus tendon (arrow) is shown on arthrogram.

Routinely, we followed patients at 2 weeks assessing absence of complications and passive rehabilitation, at 6 weeks assessing daily life activities recovery, and then at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months for clinical and radiographic assessments as described below. We attempted to contact every patient for this study. One patient was lost to followup. For the 26 athletes available for followup, the minimum followup was 19 months (mean, 47 months; range, 19–123 months). Fifteen of the 26 patients were available to complete personal interview and radiographic evaluation with a mean followup of 41 months (range, 19–87 months). We determined when patients returned to activities of daily living and when they returned to sports. Evaluation included pain, mobility, sport activity, and Constant-Murley score [6]. We evaluated pain in abduction-external rotation and posterior instability with the AP drawer sign and jerk test in flexion-adduction-internal rotation. Internal rotation was assessed by the differences in levels the patient could place their thumbs adjacent to the spinous processes compared to the normal side. Radiographic evaluation was based on AP and lateral views according to Bernageau and Patte [4] to evaluate the posterior glenoid rim, possible posterior subluxation of humeral head, and signs of osteoarthritis according to the classification of Samilson and Prieto [21]. Eleven of 26 patients were available for telephone interview only (Appendix 1), with a mean followup of 54 months (range, 20–123 months).

Results

Postoperative recovery of activity of daily living occurred between 1 and 4 weeks for 24 of 26 patients, 17 days on average. Two patients had some degree of postoperative stiffness, one recovering symmetrical passive anterior elevation after 2 months and the other after 6 months. No other postoperative complication occurred.

At last followup, no patient had residual pain in daily life. Eight athletes reported residual pain during sport. None of the patients had limitation of forward anterior elevation or external rotation. Three patients had slight limitation of internal rotation: two with a difference of two vertebral levels and one with a difference of three vertebral levels. The 15 athletes available for clinical examination at last followup had a symmetrical strength testing according to the Constant-Murley score protocol. Nine of these 15 had pain on clinical testing in forced abduction-external rotation. None had apprehension in testing posterior instability by the jerk test in flexion-adduction-internal rotation.

Eighteen of the 26 patients were able to return to their previous sport level; three were improved by the procedure but had to practice their sport at a level inferior to that before the shoulder problems; three changed their sport; and two had no improvement after the procedure. Of the latter two, one gave up javelin throwing but still played handball and the other continued to play handball despite a reported absence of improvement after the procedure. Except for one patient whose level of athletic activity plateaued at 24 months, all others plateaued before 12 months (mean, 9.5 months; range, 5–12 months).

Among the 15 patients who had radiographic evaluation, we observed no sign of arthritis or articular osteophyte at last followup (mean, 41 months; range, 19–87 months). In one patient, we suspected a minor posterior subluxation on the lateral view according to Bernageau and Patte [4] at 1-year followup; however, this patient’s shoulder appeared centered on the imaging performed in the same position 7 years after the surgery (Fig. 7).

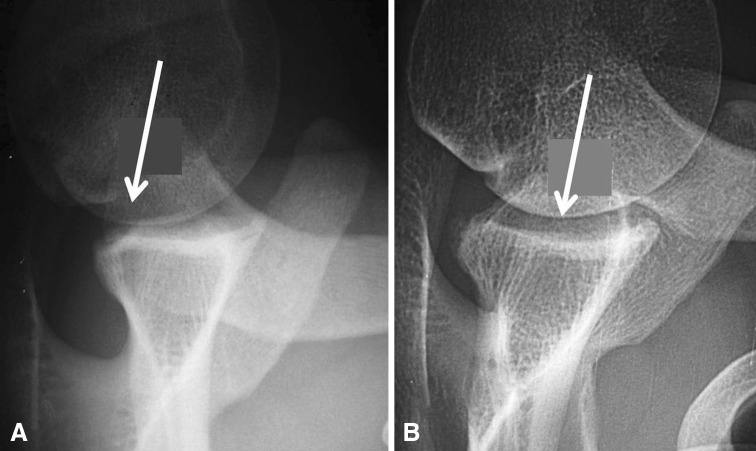

Fig. 7A–B.

(A) A lateral view described by Bernageau and Patte [4] shows minor posterior subluxation (arrow) at 1-year followup. (B) At 7-year followup, there is no posterior subluxation, with perfect concentricity of the glenoid and humeral head in the same arm position and with the same radiographic protocol.

One high-level sport athlete was revised 4 years after the index procedure for a recurrence of pain in abduction-external rotation during sport after 3 years of excellent results and return to full unrestricted volleyball. Lateral view according to Bernageau and Patte [4] showed a persisting spur on which we performed a second glenoidplasty with the possibility of resuming his former level in national league volleyball (Fig. 8). We suspect there was insufficient removal of spur during the initial procedure rather than a recurrence. We included this patient in our outcomes analysis based on his status before revision. We observed no recurrence of ossifications of the posterior glenoid rim (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8A–C.

Images illustrate the case of a patient with pain recurrence with persisting spur: (A) a glenoid spur (arrow) before the index procedure, (B) a persisting spur (arrow) at 4 years of followup, and (C) the result after smoothing the glenoid rim (arrow) after revision glenoidplasty.

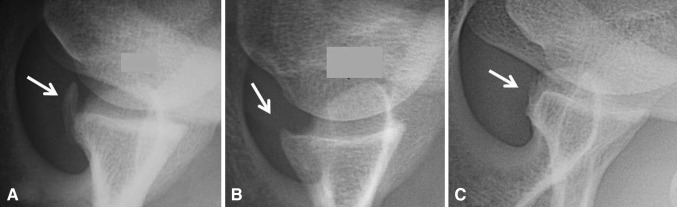

Fig. 9A–C.

Lateral views described by Bernageau and Patte [4] show the radiographic aspect of glenoidplasty. (A) Before the procedure, the posterior glenoid rim is sharp with a spur (arrow), small in this case. (B) At 1-year followup, the glenoid rim is smoothed (arrow). (C) At 6-year followup, there is no recurrence of the spur on the glenoid rim.

Discussion

Since the report in 1991 of PSGI as an internal impingement between supraspinatus tendon insertion and posterior labrum and glenoid rim [23], the standard arthroscopic procedure has been to débride tendinous and labral lesions. However, return to sports for these motivated athletes has been disappointing in the literature (Table 1) [13, 18, 20, 22]. In 1996, stimulated by the observation of large posterior glenoid spurs in two throwing athletes with PSGI, we decided to add an abrasion of the spur. Both patients achieved their former athletic level. The idea of a painful abutment on the spur seemed mechanically logical, and there was no evidence for potential complications after abrasion of excessive bone. We also noticed a posterior spur was common in throwing athletes. There had been reports of open resection of posterior ossifications in throwing athletes with unreproducible results [2, 12, 13, 16]; however, Ozaki et al. [16] reported an improvement in all parameters in a series of seven baseball pitchers and Meister et al. [13] suggested 10 of 18 players returned to their previous level of throwing. In 1996, we thus decided to generalize the glenoidplasty in arthroscopic treatment of PGSI [10]. In this report, we determined whether patients returned to their former level of play and whether the procedure relieved the pain.

Our study is subject to certain limitations. First, the small number of patients (n = 27) over a 10-year period may be explained by three factors: it is a single-surgeon (CL) study, PGSI concerns only high-level throwing athletes, and indications were initially very selective for patients with large posterior glenoid spurs. Second, only 15 of the 27 patients returned for evaluation; however, we believe the telephone questionnaire completed by 11 more athletes was reliable for determining the rate of return to sports, the principal outcome in this population and unresolved by our prior technique [20]. Third, only seven of 26 patients had more than 5 years of followup, but we believe the procedure reasonable given the first patients have now reached 10 years of followup without any posterior instability or arthritis despite extensive débridement of the posterior glenoid rim without any labral reinsertion. Fourth, six patients had less than 2 years of followup; we observe, however, outcome is achieved and stable during the first postoperative year.

The technique of glenoidplasty is standardized. The spur is frequently located slightly medial to the rim and extending below the glenoid equator. We admit that may be not consistent with the original definition of PSGI. Our current hypothesis is that mechanical impingement may occur lower on the posterior rim, according to the type of throwing movement. In cases of internal impingement without any spur, we currently perform a reaming with a motorized burr to smoothen the posterior glenoid edge. Except for two patients with postoperative stiffness, recovery was fast, 17 days on average, similar to isolated soft tissue débridement [20].

Eighteen of the 26 athletes resumed their former sport level, which is better than results previously reported (Table 1). Two athletes did not improve after the procedure: both had large partial articular-side cuff tears, which may be a reason for the unsatisfactory result. We believe partial tears of greater than 50% of the tendon thickness are a bad prognostic factor and may be repaired or discussed precisely with the athlete before the procedure. Payne et al. [18], reporting on the arthroscopic débridement of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in young athletes, described a subgroup of patients with increased anterior glenohumeral translation and posterior labral tears, with only 25% returning to sports. Meister et al. [13] reported the occasional presence of a glenoid exostosis and demonstrated débridement of the partial cuff tear and labrum with small posterior incision for removal of exostosis permitted 55% of their throwers to resume preoperative activity levels. Sonnery-Cottet et al. [22] found 22 of 28 tennis players treated with arthroscopic débridement were able to return to tennis, but 20 had persistent pain with athletic participation. In the series of Riand et al. [20], only 16% of the 75 throwing athletes were able to resume their former sport level.

We were able to confirm there was no specific complication after this procedure. Two patients had some transient shoulder stiffness, unspecific to the procedure. Despite extensive débridement of the posterior labrum precluding any attempts of reinsertion, there were no clinical or radiographic signs of posterior instability. There was neither recurrence of the spur (Fig. 9) nor glenohumeral arthritis with a followup of 19–87 months.

Regarding the pathophysiology, we believe the mechanical impingement in the late cocking phase of throwing is responsible for pain in athletes with posterior glenoid impingement. Admittedly, some other authors hold different hypotheses. Jobe and others [1, 9, 14, 17] suggest subtle anterior instability causes pain, arguing the majority of these athletes have a positive relocation test. We agree some subtle form of anterior instability may cause similar symptoms, but the athletes of our series did not show clinical or imaging signs or arthroscopic lesions of anterior instability. Indeed, Halbrecht et al. [7] found internal posterior impingement decreased with anterior instability. Burkhart et al. [5] considered the retraction of the posteroinferior capsule frequently observed in these athletes as the primary cause. They suggest contracture induces a hypertwist of the rotator cuff fibers during throwing movement, which may lead to tendon failures. We agree some of these athletes may have restricted internal rotation, and stretching of internal rotators is included in our routine rehabilitation protocol. However, this theory does not explain the glenoid spur observed for most of the patients [10, 11].

In the literature, ossifications of the posterior glenoid rim in athletes were first described by Bennett [3] in 1941 as an ossification of the triceps insertion. Some author focused on the high rate of these ossifications in asymptomatic throwing athletes [24]. In 1999, Meister et al. [13] reported on the “thrower’s exostosis,” considering the inferior ossification as the result of traction on the retracted posteroinferior capsule. Others reported posterosuperior osteophytes [15, 19]. Despite a precise analysis of these publications, we are unable to state whether the ossifications we describe in our study are different from the so-called Bennett lesions or the same entity viewed with different types of radiographs. These ossifications need a CT arthrogram (more reliable than MRI in our experience) to be precisely located on the glenoid rim itself or a few millimeters medial to the joint line, possibly at the capsule insertion, which may be consistent with the hypothesis of a traction mechanism on a retracted posteroinferior capsule. Thus, it is possible that extensive débridement of the insertion of the posteroinferior capsule contributes to the efficacy of the procedure.

In conclusion, we described arthroscopic glenoidplasty to treat findings commonly described as internal impingement. Eighteen of 26 athletes were able to return to their former level after the procedure. We observed no complications, instability, or arthritic degeneration at 19–123 months.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. N. Gaillard for organizing the clinical review.

Appendix 1

Questionnaire

Subjective opinion of the result of the operation: graded as very satisfied, satisfied, disappointed, or unsatisfied.

Did you have any complication after the operation?

Pain: How would you grade your shoulder pain, if 0 represents the maximum pain and 15 no pain?

Activity: Do you feel any impairment in professional activity or daily life, grading 0 to 4?

Do you feel any impairment in sport activity, grading 0 to 4?

Do you feel any impairment at night?

What level do you reach for activity (belt, chest, neck, head, or overhead)?

Mobility: Do you have the same mobility as before the operation or compared to the other side if normal in the three following positions: anterior elevation, external rotation with elbow at the side, and hand in the back? If not, in which sector do you feel a limitation?

Stability: Do you feel any instability of your shoulder or abnormal joint mobility?

Strength: How do you qualify the strength of your shoulder: less, same, or more than preoperatively or compared to the other side if normal?

Sport practice: Did you return to the same sport after the operation?

If yes, how do you qualify your level: inferior, same, or superior to preoperatively?

If not, which sport do you practice?

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Clinique du Parc Lyon, Lyon, France.

References

- 1.Andrews JR, Kupferman SP, Dillman CJ. Labral tears in throwing and racquet sports. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10:901–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes DA, Tullos HS. An analysis of 100 symptomatic baseball players. Am J Sport Med. 1978;6:62–67. doi: 10.1177/036354657800600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett GE. Shoulder and elbow lesions of the professional baseball pitcher. JAMA. 1941;117:510–514. doi: 10.1001/jama.1941.02820330014005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernageau J, Patte D. [The radiographic diagnosis of posterior dislocation of the shoulder] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1979;65:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part I. Pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:404–420. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;214:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halbrecht JL, Tirman P, Atkin D. Internal impingement of the shoulder: comparison of findings between the throwing and nonthrowing shoulders of college baseball players. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:253–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(99)70030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jobe CM. Posterior superior glenoid impingement: expanded spectrum. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:530–536. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvitne RS, Jobe FW. The diagnosis and treatment of anterior instability in the throwing athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;291:107–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lévigne C, Garret J, Borel F, Walch G. Arthroscopic posterior glenoplasty for postero-superior glenoid impingement. In: Boileau P, editor. Shoulder Concepts 2008: Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical Editors; 2008. pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lévigne C, Walch G. Les lésions postéro-supérieures du bourrelet glénoïdien. In: Société Annales., editor. Française d’Arthroscopie. Montpellier, France: Sauramps Medical Editors; 1999. pp. 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lombardo SJ, Jobe FW, Kerlan RK, Carter VS, Shields CL., Jr Posterior shoulder lesions in throwing athletes. Am J Sport Med. 1997;5:106–110. doi: 10.1177/036354657700500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meister K, Andrews JR, Batts J, Wilk K, Baumgartner T. Symptomatic thrower’s exostosis: arthroscopic evaluation and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:133–136. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mithöfer K, Fealy S, Altchek DW. Arthroscopic treatment of internal impingement of the shoulder. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;5:66–75. doi: 10.1097/01.bte.0000126189.02023.be. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa S, Yoneda M, Hayashida K, Mizuno N, Yamada S. Posterior shoulder pain in throwing athletes with a Bennett lesion: factors that influence throwing pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozaki J, Tomita Y, Nakagawa Y, Tamai S. Surgical treatment for posterior ossifications of the glenoid in baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:91–97. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payne LZ, Altchek DW. The surgical treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14:863–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payne LZ, Altchek DW, Craig EV, Warren RF. Arthroscopic treatment of partial rotator cuff tears in young athletes: a preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:299–305. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearce CE, Burkhart SS. The pitcher’s mound: a late sequela of posterior type-II SLAP lesions. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:214–216. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(00)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riand N, Boulahia A, Walch G. [Posterosuperior impingement of the shoulder in the athlete: results of arthroscopic debridement in 75 patients] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2002;88:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samilson RL, Prieto V. Dislocation arthropathy of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonnery-Cottet B, Edwards TB, Noel E, Walch G. Results of arthroscopic treatment of posterosuperior glenoid impingement in tennis players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:227–232. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300021401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell ST. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: an arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:238–245. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright RW, Paletta GA., Jr Prevalence of the Bennett lesion of the shoulder in major league pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2004;34:121–124. doi: 10.1177/0363546503260712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]