Abstract

Background

Current pain management protocols involving many anesthetic and analgesic drugs reportedly provide adequate analgesia after TKA. However, control of emetic events associated with the drugs used in current multimodal pain management remains challenging.

Questions/purposes

We determined (1) whether ramosetron prophylaxis reduces postoperative emetic events; and (2) whether it influences pain levels and opioid consumption in patients managed with a current multimodal pain management protocol after TKA.

Methods

We randomized 119 patients undergoing TKA to receive either ramosetron (experimental group, n = 60) or no prophylaxis (control group, n = 59). All patients received regional anesthesia, preemptive analgesic medication, continuous femoral nerve block, periarticular injection, and fentanyl-based intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. We recorded the incidence of emetic events, rescue antiemetic requirements, complete response, pain level, and opioid consumption during three periods (0–6, 6–24, and 24–48 hours postoperatively). The severity of nausea was evaluated using a 0 to 10 VAS.

Results

The ramosetron group tended to have a lower incidence of nausea with a higher complete response and tended to have less severe nausea and fewer rescue antiemetic requirements during the 6- to 24-hour period. However, the overall incidences of emetic events, rescue antiemetic requirements, and complete response were similar in both groups. We found no differences in pain level or opioid consumption between the two groups.

Conclusions

Ramosetron reduced postoperative emetic events only during the 6- to 24-hour postoperative period and did not affect pain relief. More efficient measures to reduce emetic events after TKA should be explored.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Current preemptive multimodal approaches to pain management have substantially reduced pain after TKA [32, 35–37]. However, many anesthetic and analgesic drugs used in these pain management protocols commonly provoke emetic events after total joint arthroplasty, with ranges of patients experiencing such events from 20% to 81% [7, 20, 21, 26]. This contrasts with 15% to 51% using traditional postoperative (nonmultimodal) approaches to pain control [16, 23, 38]. The increase in incidence and severity in iatrogenic nausea and vomiting makes postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) important for patients and healthcare providers. PONV reportedly is more distressing to patients than postoperative pain [17, 27, 31, 34], and inadequate management of pain and emesis is associated with patient dissatisfaction [8, 34]. Furthermore, prolonged PONV can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, delayed oral intake, and airway compromise, which results in delayed recovery and compromised outcomes [1, 15, 17, 29].

Several studies report variable responses to specific antiemetic drugs [17, 18, 29]. Among various antiemetic drugs tried, serotonin receptor antagonists such as ondansetron [39], granisetron [41], and dolasetron [19] are the most commonly used to prevent PONV. Unfortunately, typically they have a too short duration of action to cover the immediate postoperative period and are limited to an antivomiting action rather than an antinausea action [6, 22, 24]. Several studies found ramosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has more potent and longer-acting properties than do other serotonin receptor antagonists [6, 10–12, 20, 30]. In one study ramosetron reduced the incidence of PONV during the postoperative 2- to 24-hour period compared with ondansetron in patients who were highly susceptible to PONV because of patient factors and drugs used for pain management after TKA [20]. However, the antiemetic efficacy achieved by ramosetron prophylaxis compared with no prophylaxis after TKA remains unclear. Additionally, whether ramosetron influences postoperative pain relief is not well defined.

We therefore sought to determine (1) whether the prophylactic use of ramosetron reduced the incidence of PONV, the severity of nausea, the need for rescue antiemetics, and increased the complete response; and (2) whether ramosetron prophylaxis influenced the postoperative pain level and opioid consumption in patients undergoing TKA who were managed with a contemporary preemptive multimodal pain control protocol.

Patients and Methods

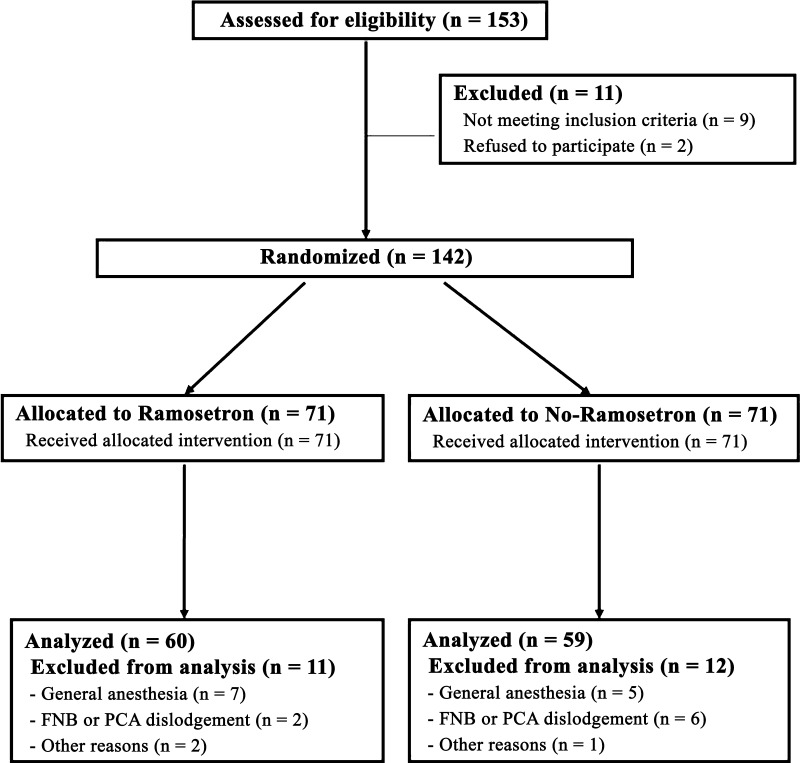

We randomized 119 patients undergoing TKA between September 2009 and February 2010 to receive either ramosetron (experimental group, n = 60) or no prophylaxis (control group, n = 59). During that same time, we treated a total of 259 patients with TKA. In the trial we included only patients with primary osteoarthritis who underwent unilateral TKA and who agreed to participate. We excluded patients with a history of intolerance or allergy to any drugs used in the study, severe bowel motility impairment, the administration of another antiemetic drug or systemic steroid 24 hours before surgery, a history of cardiovascular or respiratory disease, alcohol or opioid dependence, and renal or hepatic functional impairments. In addition, we excluded patients when regional anesthesia was contraindicated, when spinal anesthesia failed, or when femoral nerve block or/and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia were discontinued before the planned schedule. After assessing 153 patients for eligibility, we excluded 11 patients before enrollment for various reasons, which left 142 patients for randomization (Fig. 1). A computer-generated randomization table permuted into blocks of four and six was created by a statistician who did not participate in this study. It was used to assign patients to one of the two groups, the experimental group that received ramosetron (Nasea; Astellas, Tokyo, Japan; $37 US per ampule) prophylaxis or the control group that did not. One of two anesthesiologists (JYT, RJH) telephoned a surgeon (KTK) who was not involved in patient recruitment for this trial for allocation consignment just before surgery. The patients and an independent investigator (KBY) who collected all clinical information prospectively were unaware of group assignments until completion of the final data analyses. Seventy-one patients initially were allocated to the ramosetron group and the other 71 to the control group. We excluded 11 patients in the ramosetron group and 12 in the control group according to the defined exclusion criteria, leaving 119 patients (60 in the ramosetron group versus 59 in the control group) for analysis. Final outcome adjudications were completed in March 2010, and the study protocol was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01102491, “The Effect of Multimodal Anti-emetic Protocol on Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting After Total Knee Arthroplasty”). To determine the number of patients required, we performed a priori power analysis based on the results of a pilot study showing an incidence of PONV of 55% in 20 patients not treated with ramosetron. One hundred twelve patients (56 in each group) were required to detect a 50% reduction in the incidence of PONV at an alpha level of 0.05 and with a power of 80% using a two-sided test. To allow for exclusions and dropouts, we enrolled 153 patients after approval was granted by our Institutional Review Board.

Fig. 1.

A flow diagram of subject progress is shown. FNB = femoral nerve block; PCA = patient-controlled analgesia.

There were no differences between the two groups in terms of demographic data and number of risk factors for PONV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and the risk factors for PONV in the ramosetron and control groups

| Parameters | Ramosetron group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 59) | Significance (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data* | |||

| Age (years) | 69.1 (6.3) | 69.0 (7.5) | 0.895 |

| Gender (female) | 53 (88%) | 53 (90%) | 0.793 |

| Height (cm) | 153.5 (6.9) | 153.6 (7.1) | 0.957 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.0 (10.1) | 64.3 (10.2) | 0.874 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.1 (3.4) | 27.2 (3.8) | 0.803 |

| Risk factors for PONV | |||

| Duration of surgery (minutes) | 106.8 (14.0) | 107.0 (14.1) | 0.917 |

| Risk factors identified† | 0.682 | ||

| With one factor | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| With two factors | 3 (5) | 5 (9) | |

| With three factors | 52 (87) | 51 (86) | |

| With four factors | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Calculated mean risk‡ | 57.3 (11.8) | 58.1 (9.4) | 0.682 |

* Data are presented as means with SDs in parentheses, except for sex, which is presented as number of female patients and their percentages in parentheses; †data are presented as numbers of patients with risk factors with their proportions in parentheses; the four risk factors described by Murphy et al. [33]; ‡data are presented as calculated mean risk for PONV as determined using the simplified risk scoring system described by Apfel et al. [2] with SDs in parentheses; PONV = postoperative nausea and vomiting.

All patients received the same anesthetic and multimodal pain management protocol, except that 0.3 mg ramosetron was administered intravenously at the end of surgery only to the ramosetron group. Briefly, oral analgesic drugs (10 mg oxycodone SR, 200 mg celecoxib, 75 mg pregabalin, and 650 mg acetaminophen) were administered for preoperative preemptive analgesia on a call basis to all 119 patients before surgery. All patients were premedicated with 0.03 mg/kg midazolam intravenously 30 minutes before induction and received a continuous femoral nerve block (a bolus injection of 30 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine solution followed by a continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine solution at 5 mL/hour). Spinal anesthesia was administered with 10 to 15 mg 0.5% bupivacaine by one of two anesthesiologists (JYT, RJH). The spinal anesthesia and femoral nerve block were verified to have achieved a complete block before making an operative incision. Anesthesia was maintained with propofol (target blood concentration 0.8–1.5 μg/mL) using a target-controlled device (Orchestra; Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany), and O2 was delivered through a partial rebreathing mask bag at a flow rate of 5 L/minute (FiO2 0.4). All patients received periarticular injections with a multimodal drug cocktail comprising 300 mg ropivacaine, 10 mg morphine sulfate, 30 mg ketorolac, 300 μg 1:1000 epinephrine, and 750 mg cefuroxime after all prostheses had been fixed with cement [26].

All surgeries were performed by one surgeon (KTK) using the standard medial parapatellar arthrotomy with a tourniquet. A posteriorly stabilized prosthesis (Genesis II; Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA) was implanted in all patients. The patella was resurfaced in all cases, and cement fixation was used for all components.

Postoperatively, all patients received intravenous patient-controlled analgesia, which was programmed to deliver 1 mL of a 100-mL solution containing 2000 μg fentanyl for patients who were 70 years or younger or 1500 μg for patients older than 70 years when patients depressed a button with a 10-minute lockout period. Once patients resumed oral intake, 200 mg celecoxib, 75 mg pregabalin, and 650 mg acetaminophen were administered every 12 hours. An intramuscular injection of ketoprofen (100 mg) was used for acute pain rescue when a patient reported pain of severity greater than 6 on a 0 to 10 VAS. The continuous femoral nerve block and the intravenous patient-controlled analgesia typically were discontinued on the third and fourth postoperative days, respectively, or sooner if the intravenous patient-controlled analgesia pump had been emptied. An intravenous injection of 10 mg metoclopramide was used as a first-line rescue antiemetic treatment when patients experienced two or more episodes of PONV or had severe nausea (> 4 on a 0–10 VAS) [4]. If severe nausea persisted after two consecutive boluses of metoclopramide in a 30-minute interval, 4 mg ondansetron was administered intravenously as the second-line treatment.

A clinical investigator (KBY) blinded to randomization details prospectively collected demographic data and assessed the risk factors for PONV using predesigned data sheets according to the recommendation of consensus guidelines for the management of PONV [3, 17]. Risk factors and calculated mean risks for PONV were evaluated using the simplified risk scoring system devised by Apfel et al. [2]. This scoring system includes four risk factors, namely female gender, history of PONV or motion sickness, nonsmoking status, and the use of postoperative opioids. The predicted incidences of PONV given the presence of one, two, three, or four of these risk factors are reportedly 21%, 39%, 61%, and 78%, respectively [1, 2].

The primary outcome variables were incidence of PONV and severities of nausea during three postoperative periods (0–6 hours, 6–24 hours, and 24–48 hours). All episodes of nausea and vomiting during these three periods were recorded by the previously noted clinical investigator (KBY). Nausea was defined as a subjective unpleasant sensation associated with the awareness of the urge to vomit and vomiting as the forceful expulsion of gastric contents from the mouth [40]. The severity of nausea was assessed by patients using a 0 to 10 VAS (the left end [0] corresponded to no nausea and the right end [10] to the worst imaginable nausea). Preoperatively, patients were instructed by the clinical investigator (KBY) to make a mark on the line to represent their level of perceived symptom intensity on the VAS scale in the predesigned data sheet.

The secondary outcome variables were number of times rescue antiemetics were required, whether a complete response to the administered rescue antiemetics was achieved, pain level, and amount of opioid consumption (determined using the intravenous patient-controlled analgesia pump for the three periods). Complete response to an administered rescue antiemetic was defined as no additional experience of nausea and vomiting without the need for another rescue antiemetic [28]. Pain levels were estimated using a VAS that ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) for the three periods. Amounts of opioid (fentanyl) consumption also were recorded for each of the three periods and summed to obtain consumption over the entire study period. The incidences of nausea and vomiting were determined for the three periods and for the whole study period by calculating the proportions of patients who experienced nausea and/or vomiting. Additionally, the severity of nausea was assessed using a 0 to 10 VAS scale for patients who had experienced nausea during each study period.

We compared the ramosetron and control groups with respect to primary and secondary outcomes. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine differences in categorical variables, namely sex, presence of PONV risk factors, the incidence of nausea and vomiting, requirements for rescue antiemetics, and proportion of complete response to the administered rescue antiemetics. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare continuous variables, namely VAS pain score and the amount of opioid consumption through the intravenous patient-controlled analgesia pump, and Student’s t-test was used to compare age, height, weight, BMI, duration of surgery, and calculated mean risk. The variables subjected to multiple comparison included the incidence of nausea and vomiting, the severity of nausea, requirement for rescue antiemetics, the proportion of complete response, VAS pain scores, and the amount of opioid consumption between groups; these were analyzed with repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni corrected post hoc analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (Version 15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Prophylactic use of ramosetron tended to reduce the incidence of nausea (p = 0.017 or 0.051 with Bonferroni correction) but not the incidence of vomiting (p = 0.241), and it tended to improve the rate of complete response and reduce the severity of nausea and need for rescue antiemetics during the 6- to 24-hour period after surgery. However, the overall incidence of PONV, severity of nausea, rescue antiemetic requirement, and complete response were similar in the ramosetron and control groups during the entire study period. During the 6- to 24-hour period, the incidence of nausea was lower (p = 0.051) in the ramosetron group than in the control group (23% versus 44%) (Table 2), and the ramosetron group tended to experience less severe nausea (p = 0.09) than the control group (1.0 versus 1.7) (Table 3). A smaller proportion (p = 0.069) of patients in the ramosetron group tended to require the use of rescue antiemetics (20% versus 39%) and more patients (p = 0.051) in the ramosetron group had a complete response (77% versus 56%) (Table 4). However, no differences were noticed during the other two periods (p = 0.312 during 0-6 hours and p = 0.286 during 24–48 hours) or in the incidence of vomiting among the three periods.

Table 2.

Incidences of emetic events in the ramosetron and control groups*

| Parameter | Ramosetron group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 59) | Significance† (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 25 (42) | 32 (54) | 0.170 |

| 0–6 hours | 21 (35) | 26 (44) | 0.312 (0.936) |

| 6–24 hours | 14 (23) | 26 (44) | 0.017 (0.051) |

| 24–48 hours | 3 (5) | 6 (10) | 0.286 (0.858) |

| Vomiting | 12 (20) | 20 (34) | 0.087 |

| 0–6 hours | 10 (17) | 14 (24) | 0.337 (1.000) |

| 6–24 hours | 5 (8) | 9 (15) | 0.241 (0.723) |

| 24–48 hours | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.157 (0.471) |

* Data are presented as numbers of patients who experienced nausea or vomiting with their proportions in parentheses. †p values in parentheses have been corrected by Bonferroni analysis.

Table 3.

Comparisons of the severity of nausea in the ramosetron and control groups*

| Parameter | Ramosetron group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 59) | Significance† (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 hours | 1.8 (2.8) | 2.4 (3.1) | 0.291 (0.873) |

| 6–24 hours | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.7 (2.3) | 0.030 (0.090) |

| 24–48 hours | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.198 (0.594) |

* Data are presented as means with SDs in parentheses using the VAS, where 0 indicates no nausea and 10 the worst imaginable nausea; †p values in parentheses have been corrected by Bonferroni analysis.

Table 4.

Requirement for rescue antiemetics and the frequency of complete response to administered rescue antiemetics*

| Parameter | Ramosetron group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 59) | Significance† (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rescue antiemetics | 20 (33) | 28 (48) | 0.116 |

| 0–6 hours | 18 (30) | 22 (37) | 0.400 (1.000) |

| 6–24 hours | 12 (20) | 23 (39) | 0.023 (0.069) |

| 24–48 hours | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 0.983 (1.000) |

| Complete response‡ | 35 (58) | 27 (46) | 0.170 |

| 0–6 hours | 39 (65) | 33 (56) | 0.312 (0.936) |

| 6–24 hours | 46 (77) | 33 (56) | 0.017 (0.051) |

| 24–48 hours | 56 (93) | 53 (90) | 0.491 (1.000) |

* Data are presented as numbers of patients with proportions in parentheses; †p values in parentheses have been corrected by Bonferroni analysis. ‡the complete response was defined as no additional postoperative nausea and vomiting nor the requirement for rescue antiemetics [28].

The pain level, opioid consumption through the intravenous patient-controlled analgesia pump, and frequency of acute pain rescue were similar in both groups during the entire study period. No group differences were found in terms of mean VAS pain scores, opioid consumption, or frequency of use of acute pain rescue during any of the three periods (p > 0.1 in all comparisons) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparisons of pain level, opioid (fentanyl) consumption through IV-PCA, and frequency of acute pain rescue in the ramosetron and control groups*

| Parameter | Ramosetron group (n = 60) | Control group (n = 59) | Significance (p value)|| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain score (VAS)† | |||

| 0–6 hours | 1.1 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.858 (1.000) |

| 6–24 hours | 3.9 (1.5) | 4.3 (1.6) | 0.161 (0.483) |

| 24–48 hours | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.9 (1.4) | 0.081 (0.243) |

| Fentanyl consumption (μg)‡ | |||

| 0–6 hours | 28.4 (24.8) | 26.0 (22.5) | 0.582 (1.000) |

| 6–24 hours | 134.4 (120.5) | 108.5 (79.4) | 0.169 (0.507) |

| 24–48 hours | 184.4 (161.4) | 158.7 (112.4) | 0.317 (0.951) |

| Whole 48-hour period | 347.3 (257.0) | 293.2 (172.8) | 0.182 |

| Acute pain rescue§ | |||

| 0–6 hours | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 0.926 (1.000) |

| 6–24 hours | 17 (28) | 21 (36) | 0.349 (1.000) |

| 24–48 hours | 29 (48) | 23 (39) | 0.242 (0.726) |

| Whole 48-hour period | 42 (70) | 43 (73) | 0.718 |

IV-PCA = intravenous patient-controlled analgesia; * data are presented as means with SDs in parentheses; †pain scores were assessed using the VAS (0 indicates no pain, and 10 the worst imaginable pain); ‡amount of fentanyl consumption through IV-PCA was measured; §numbers of patients requiring acute pain rescue more than once are presented with their proportions in parenthesis; ||p values in parentheses have been corrected by Bonferroni analysis.

Discussion

Current trends in pain management after TKA are toward involving potent anesthetic and analgesic agents that commonly provoke emesis, and so PONV remains a challenging issue. Only one previous study has reported that ramosetron is more potent and longer acting compared with ondansetron after TKA [20]. We therefore determined (1) whether ramosetron prophylaxis reduces postoperative emesis in terms of the incidence of nausea and vomiting, severity of nausea, and requirement for rescue antiemetics; and (2) whether it influences pain levels and opioid consumption compared with no prophylaxis in patients managed with our current multimodal pain management protocol after TKA.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, all patients were Korean, and most were older than 61 years. Although age and ethnicity are not clearly identified risk factors for PONV, they could be associated with the incidence of PONV, and thus these factors should be considered before extrapolating our findings to other populations [15, 33]. Second, 11 of 153 enrolled patients (7%) and 23 of 142 allocated patients (16%) were excluded from this study. However, because the incidence and severity of PONV are known to be influenced by numerous factors including patient, anesthesia, and surgery factors [1–3, 15, 17, 28, 29, 40], we were compelled to apply strict exclusion criteria to provide equal perioperative conditions in both groups to detect subtle differences. Thus, we excluded all patients who had experienced events that may have affected the incidence and severity of PONV. Third, partially ineffective blinding to the treatment assignment may have influenced the results because the control group did not receive a placebo or any prophylactic treatment. However, ramosetron was administered at the end of surgery by one of two nonblinded anesthesiologists (JYT, RJH), and all patients were unconscious because anesthesia was maintained with propofol during the procedure. Fourth, our anesthetic regimen included some components designed to reduce the baseline risk of PONV such as midazolam premedication, propofol maintenance, intraoperative oxygen supplement, and sufficient hydration, which might have influenced measures of the incidence and severity of PONV [9, 17, 24]; therefore, the pure antiemetic effect achieved by ramosetron may not be depicted precisely by our results. Nevertheless, the antiemetic character of our anesthetic regimen was considered necessary on ethical grounds for patients at high risk for PONV in the control group. Fifth, we did not document the incidence of the side effects of ramosetron in this study. The most frequently reported side effects of serotonin receptor antagonists are headache, dizziness, and drowsiness. However, most anesthetic and analgesic agents used in this study can result in similar, but more potent, side effects. Therefore, we believe the clinical relevance of this is questionable in patients who were managed with our pain management protocol. Nevertheless, there were no differences in terms of the incidence of these events between the two groups, and some previous studies have confirmed the safety of ramosetron [6, 14, 20, 30]. Finally, we showed the statistical significance of our multiply compared variables using their original values and values after Bonferroni analysis. Because Bonferroni correction is too conservative to detect clinical relevance and requires a much larger sample size, we believe it is inappropriate to determine the clinical importance based on an arbitrary statistical value. Thus, care should be taken when interpreting our data based solely on statistical levels.

Our findings partly support the suggestion that prophylactic use of ramosetron could reduce the incidence of PONV, the severity of nausea, and the requirement for rescue antiemetics and improve the complete response compared with no prophylaxis. In this study, the prophylactic antiemetic effect of ramosetron was not complete and was limited to only 6 to 24 hours postoperatively. Our findings concur with those of two previous studies that evaluated the antiemetic effect of ramosetron prophylaxis after major orthopaedic surgery [6, 20]. In those studies, it was concluded that ramosetron had an antiemetic effect on PONV at 2 to 6 hours after surgery. Thus, ramosetron acted mainly on late PONV that develops 2 to 6 hours after surgery that is related to opioid use rather than to early PONV, which is associated with anesthetic factors. Meanwhile, the duration of the prophylactic antiemetic effect of a single bolus of ramosetron has been reported to last up to 48 hours [10, 11, 13]. However, its antiemetic effect in this study was limited to the 6- to 24-hour period after surgery. Although ramosetron reportedly is more potent and longer acting than other serotonin receptor antagonists [10, 13], the exact duration of action after TKA in patients highly susceptible to PONV is unknown. Our finding that a single ramosetron prophylaxis has limited antiemetic efficacy in patients undergoing TKA who were highly susceptible to PONV suggests antiemetic prophylaxis based on combinations of antiemetic drugs of different classes should be adopted [15, 17], and an additional dose of ramosetron might be considered to reduce PONV 24 hours after TKA.

However, our data suggest the incidence of PONV in patients undergoing TKA managed with a current multimodal pain control protocol is high. In this study, the overall incidence of PONV in the ramosetron group 48 hours after surgery was 42%. Our findings concur with those of several studies on the incidence of PONV as a primary outcome variable after total joint arthroplasty, which have reported incidences from 25% to 56% [5, 7, 20, 21] (Table 6). Of these four studies, two retrospective studies [7, 21] showed the antiemetic efficacy of aprepitant, and two prospective randomized trials [5, 20] compared the antiemetic efficacy of ramosetron and prochloperazine with ondansetron. However, there was marked interstudy heterogeneity regarding the anesthetic and concomitant pain management protocol. Our findings, when taken together with those of previous studies, indicate a substantial number of patients managed using current multimodal pain management protocols experience PONV after TKA, showing adequate preventive PONV management strategies should be adopted.

Table 6.

Summary of studies on postoperative emetic events in major orthopaedic surgery

| Study | Study design | Prophylactic regimen | Anesthesia and pain control protocol | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. [5] (1998) | Prospective randomized trial; | 37 ondansetron (4 mg) versus 41 prochloperazine (10 mg) | General or regional anesthesia | Study period: 48 hours |

| 87 THAs or TKAs | Epidural PCA (morphine or fentanyl) | Incidence: lower with prochlorperazine (81% versus 56%) | ||

| Regular oral analgesics | Severity: less severe with prochlorperazine | |||

| Rescue: less frequent with prochlorperazine | ||||

| Choi et al. [6] (2008) | Prospective randomized trial; | 47 ramosetron (0.3 mg) versus 47 ondansetron (4 mg) | General anesthesia | Study period: 0–6, 6–24, and 24–48 hours |

| 94 spine surgeries | IV-PCA (fentanyl) | Incidence: no difference (62% versus 70%) | ||

| Severity: less with ramosetron 6–24 hours | ||||

| Rescue: less frequent with ramosetron 6–24 hours | ||||

| Pain: lower with ramosetron 24–48 hours | ||||

| Opioid: less with ramosetron | ||||

| Hatrick et al. [21] (2010) | Retrospective; | 12 aprepitant (40 mg) versus | Spinal anesthesia with EREM (5–12.5 mg) | Study period: 48 hours |

| 24 TKAs | 12 ondansetron (4 mg) + dexamethasone (4–6 mg) and metoclopramide (10 mg), diphenhydramine (25 mg) or prochloperazine (5 mg) | Incidence: lower with aprepitant (25% versus 75%) | ||

| Pain: no difference | ||||

| Dilorio et al. [7] (2010) | Retrospective; | 50 aprepitant (40 mg) versus | Spinal anesthesia except one case | Study period: entire hospital stay |

| 100 THAs or TKAs | 50 no prophylaxis | Incidence: lower with aprepitant (28% versus 70%) | ||

| Severity: less severe with aprepitant | ||||

| Rescue: less than one dose with aprepitant (0.61 dose versus 1.25 dose) | ||||

| Opioid: no difference | ||||

| Hahm et al. [20] (2010) | Prospective randomized trial; | 42 ramosetron (0.3 mg) versus | Spinal anesthesia | Study period: 0–2, 2–6, 6–24, and 24–48 hours |

| 84 TKAs | 42 ondansetron (4 mg) | Epidural PCA (ropivacaine + hydromorphone) | Incidence: lower with ramosetron 2–24 hours | |

| Severity: less severe with ramosetron 2–48 hours | ||||

| Rescue: lower with ramosetron 24–48 hours | ||||

| Opioid: no difference | ||||

| Current study | Prospective randomized trial; | 60 ramosetron (0.3 mg) versus | Spinal anesthesia | Study period: 0–6, 6–24, and 24–48 hours |

| 119 TKAs | 59 no prophylaxis | Preemptive oxycodone, celecoxib, pregabalin, acetaminophen | Incidence: no difference (42% versus 54%), lower with ramosetron 6–24 hours | |

| Continuous femoral nerve block | Severity: no difference | |||

| Periarticular injection | Rescue: no difference | |||

| IV-PCA (fentanyl) | Pain: no difference | |||

| Regular celecoxib, pregabalin, acetaminophen | Opioid: no difference |

PCA = patient-controlled analgesia; IV = intravenous; EREM = extended-release epidural morphine.

Our data suggest ramosetron does not influence pain level or opioid consumption. No differences in postoperative pain level or opioid consumption were found. Because the fear of emesis can lead to avoidance of opioid use, this may affect postoperative pain level and opioid consumption. Thus, more effective control of PONV might improve pain relief by allowing more intended use of opioid. However, reports on this issue are contradictory [6, 7, 20–22, 25, 40]. Our findings concur with those of some previous studies that showed no difference in pain level or opioid consumption regardless of antiemetic modality [7, 20, 21], but not with other studies that found that more effective antiemesis is associated with superior postoperative pain relief [6, 22, 25, 40]. The reasons why PONV control was not associated with pain level in this study are unclear, but this failure may be the result of the limited antiemetic effects of ramosetron prophylaxis or of the effect on pain relief of reducing opioid consumption. The latter was provided by our multimodal pain control protocol, which makes it difficult to detect differences mediated only by the antiemetic therapy.

Our study showed prophylactic use of ramosetron reduces the incidence of PONV and improved the complete response, but it is effective only for a 6- to 24-hour period after surgery. Additionally, we found ramosetron prophylaxis did not influence pain level or opioid consumption. More efficient and comprehensive measures to reduce emetic events after TKA should be explored to complement the current multimodal pain management protocol.

Acknowledgment

We thank Bong Young Kong MD, of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for data collection and patient interviews.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (KTK) received funding from the clinical research fund of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent was obtained.

This work was performed at the Joint Reconstruction Center, Seoul National University, Bundang Hospital, Seongnamsi, Korea.

References

- 1.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, Zernak C, Danner K, Jokela R, Pocock SJ, Trenkler S, Kredel M, Biedler A, Sessler DI, Roewer N. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apfel CC, Roewer N, Korttila K. How to study postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:921–928. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boogaerts JG, Vanacker E, Seidel L, Albert A, Bardiau FM. Assessment of postoperative nausea using a visual analogue scale. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:470–474. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen JJ, Frame DG, White TJ. Efficacy of ondansetron and prochlorperazine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after total hip replacement or total knee replacement procedures: a randomized, double-blind, comparative trial. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2124–2128. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.19.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi YS, Shim JK, Yoon do H, Jeon DH, Lee JY, Kwak YL. Effect of ramosetron on patient-controlled analgesia related nausea and vomiting after spine surgery in highly susceptible patients: comparison with ondansetron. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:E602–E606. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817c6bde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilorio TM, Sharkey PF, Hewitt AM, Parvizi J. Antiemesis after total joint arthroplasty: does a single preoperative dose of aprepitant reduce nausea and vomiting? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2405–2409. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorr LD, Chao L. The emotional state of the patient after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;463:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii Y. Clinical strategies for preventing postoperative nausea and vomitting after middle ear surgery in adult patients. Curr Drug Saf. 2008;3:230–239. doi: 10.2174/157488608785699423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii Y, Saitoh Y, Tanaka H, Toyooka H. Comparison of ramosetron and granisetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynecologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:476–479. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199908000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii Y, Saitoh Y, Tanaka H, Toyooka H. Ramosetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in women undergoing gynecological surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:472–475. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200002000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii Y, Tanaka H. Prevention of nausea and vomiting with ramosetron after total hip replacement. Clin Drug Investig. 2003;23:405–409. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200323060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii Y, Tanaka H, Kawasaki T. Benefits and risks of granisetron versus ramosetron for nausea and vomiting after breast surgery: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Ther. 2004;11:278–282. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000101829.94820.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujii Y, Toyooka H, Tanaka H. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in female patients during menstruation: comparison of droperidol, metoclopramide and granisetron. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:248–249. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan TJ. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1884–1898. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219597.16143.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gan TJ, Alexander R, Fennelly M, Rubin AP. Comparison of different methods of administering droperidol in patient-controlled analgesia in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:81–85. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199501000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, Kovac A, Philip BK, Sessler DI, Temo J, Tramer MR, Watcha M. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62–71. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068580.00245.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golembiewski J, Tokumaru S. Pharmacological prophylaxis and management of adult postoperative/postdischarge nausea and vomiting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21:385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graczyk SG, McKenzie R, Kallar S, Hickok CB, Melson T, Morrill B, Hahne WF, Brown RA. Intravenous dolasetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after outpatient laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:325–330. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199702000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahm TS, Ko JS, Choi SJ, Gwak MS. Comparison of the prophylactic anti-emetic efficacy of ramosetron and ondansetron in patients at high-risk for postoperative nausea and vomiting after total knee replacement. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:500–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartrick CT, Tang YS, Hunstad D, Pappas J, Muir K, Pestano C, Silvasi D. Aprepitant vs. multimodal prophylaxis in the prevention of nausea and vomiting following extended-release epidural morphine. Pain Pract. 2010;10:245–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jellish WS, Leonetti JP, Sawicki K, Anderson D, Origitano TC. Morphine/ondansetron PCA for postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting after skull base surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauste A, Tuominen M, Heikkinen H, Gordin A, Korttila K. Droperidol, alizapride and metoclopramide in the prevention and treatment of post-operative emetic sequelae. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1986;3:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kazemi-Kjellberg F, Henzi I, Tramer MR. Treatment of established postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review. BMC Anesthesiol. 2001;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MK, Nam SB, Cho MJ, Shin YS. Epidural naloxone reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients receiving epidural sufentanil for postoperative analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:270–275. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koh IJ, Kang YG, Chang CB, Kwon SK, Seo ES, Seong SC, Kim TK. Additional pain relieving effect of intraoperative periarticular injections after simultaneous bilateral TKA: a randomized, controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:916–922. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koivuranta M, Laara E, Snare L, Alahuhta S. A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.117-az0113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korttila K. The study of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69(7 suppl 1):20S–23S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kovac AL. Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2000;59:213–243. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee D, Kim JY, Shin JW, Ku CH, Park YS, Kwak HJ. The effect of oral and IV ramosetron on postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopy with total intravenous anesthesia. J Anesth. 2009;23:46–50. doi: 10.1007/s00540-008-0693-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652–658. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maheshwari AV, Blum YC, Shekhar L, Ranawat AS, Ranawat CS. Multimodal pain management after total hip and knee arthroplasty at the Ranawat Orthopaedic Center. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1418–1423. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0728-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy MJ, Hooper VD, Sullivan E, Clifford T, Apfel CC. Identification of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting in the perianesthesia adult patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myles PS, Williams DL, Hendrata M, Anderson H, Weeks AM. Patient satisfaction after anaesthesia and surgery: results of a prospective survey of 10, 811 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:6–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parvataneni HK, Shah VP, Howard H, Cole N, Ranawat AS, Ranawat CS. Controlling pain after total hip and knee arthroplasty using a multimodal protocol with local periarticular injections: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parvizi J, Porat M, Gandhi K, Viscusi ER, Rothman RH. Postoperative pain management techniques in hip and knee arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:769–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters CL, Shirley B, Erickson J. The effect of a new multimodal perioperative anesthetic regimen on postoperative pain, side effects, rehabilitation, and length of hospital stay after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singelyn FJ, Deyaert M, Joris D, Pendeville E, Gouverneur JM. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous three-in-one block on postoperative pain and knee rehabilitation after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:88–92. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199807000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tramer MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1277–1289. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–184. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson AJ, Diemunsch P, Lindeque BG, Scheinin H, Helbo-Hansen HS, Kroeks MV, Kong KL. Single-dose i.v. granisetron in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:515–518. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]