Abstract

Identification of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an essential first step in developing interventions to prevent or delay disease onset. In this study, we examine the hypothesis that deeper analyses of traditional cognitive tests may be useful in identifying subtle but potentially important learning and memory differences in asymptomatic populations that differ in risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Subjects included 879 asymptomatic higher-risk persons (middle-aged children of parents with AD) and 355 asymptotic lower-risk persons (middle-aged children of parents without AD). All were administered the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test at baseline. Using machine learning approaches, we constructed a new measure that exploited finer differences in memory strategy than previous work focused on serial position and subjective organization. The new measure, based on stochastic gradient descent, provides a greater degree of statistical separation (p =1.44 × 10−5) than previously observed for asymptomatic family history and non-family history groups, while controlling for apolipoprotein epsilon 4, age, gender, and education level. The results of our machine learning approach support analyzing memory strategy in detail to probe potential disease onset. Such distinct differences may be exploited in asymptomatic middle-aged persons as a potential risk factor for AD. (JINS, 2012, 18, 1–12)

Keywords: Cohort study, Memory, Neuropsychological tests, Pre-symptomatic disease, Statistical models, Medical informatics

INTRODUCTION

A recent National Institute of Aging and Alzheimer’s Association workgroup articulated the need to better define preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) for future clinical research studies (Sperling et al., 2011). Because some AD risk factors are potentially addressable (Hendrie et al., 2006), early identification of persons with preclinical AD may help to prevent or delay disease onset. The present study explores the use of translational computational approaches in cognitive testing to identify high and low risk AD population differences.

Cognitive Testing in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease

Longitudinal cognitive testing has been used to identify asymptomatic persons thought to be at risk for AD. The Framingham Study, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging and the Nun Study described cognitive changes 10 or more years before disease onset in verbal learning, abstract reasoning, visual learning, and verbal narratives (Elias et al., 2000; Kawas et al., 2003; Snowdon et al., 1996). A meta-analysis of cognitive changes in preclinical AD showed statistical differences in areas such as episodic memory (Bäckman, Jones, Berger, Laukka, & Small, 2005). However, the lowest mean age of participants in these studies was 62 years and a third of the subjects were 75 years or older at the time of baseline testing. Current models suggest that AD pathogenesis may begin as early as 20 years before diagnosis (Braak & Braak, 1990); consequently, the search for subtle cognitive changes that may correlate with preclinical AD pathology has assumed a new importance (Sperling et al., 2011).

Previous work has focused on list learning tests for differentiating cognitively normal persons from those with AD. Although summary scores from such tests may differentiate Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or AD from normal aging (Grundman et al., 2004; Welsh, Butters, Hughes, Mohs, & Heyman, 1991), additional performance measures that reflect specific aspects of the learning process have also proven useful. On lists comprised of unrelated words, such as the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) (Lezak, Howieson & Loring, 2004; Rey, 1964), differences were noted between persons with AD and controls on measures including serial position effects and subjective organization. Persons with AD, even at mild stages, disproportionately recall words from the end of a supraspan list (“recency effect”) compared to words at the beginning of the list (“primacy effect”) (Capitani, Della Sala, Logie, & Spinnler, 1992). These differences, which may signal compensation for weak consolidation in episodic memory processing, are consistent with compromised function of the hippocampus (Hermann et al., 1996) and other mesial temporal brain regions, which is characteristic of this disease (Jack et al., 1999; Killiany et al., 2000). Persons with AD also are less likely to impose and consistently use subjective organization procedures—that is, combinations of words remembered together in subsequent trials (Ramakers et al., 2008). Subjective organization reflects an idiosyncratic organization imposed by the individual, instead of responses to obvious semantic relationships (Bousfield & Bousfield, 1966; Tulving, 1962). The active organization that this requires may involve a combination of executive function—for example, working memory—and semantic memory. As a result, AD-related reductions in subjective organization may stem from changes in the prefrontal cortex (Ramakers et al., 2010) and/or temporoparietal regions (Wolk, Dickerson, & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2011).

Supplementary learning measures have also been studied in non-demented persons who were at increased risk of developing AD. Regarding serial position effects, Howieson et al. (2010) observed an intermediate level of primacy during AVLT testing for persons diagnosed with MCI compared to cognitively normal controls and persons with AD. La Rue et al. (2008) showed a small but statistically significant serial position effect in a middle-aged sample where asymptomatic persons with a parental family history of AD exhibited reduced primacy effects on the AVLT compared to controls without a parental family history of AD. Ramakers et al. (2010) measured subjective organization in the AVLT and found less subjective organization for patients diagnosed with MCI that progressed to AD as opposed to patients diagnosed with MCI that did not progress to AD.

Family History and AD Risk

Epidemiologic research indicates that a first-degree family history of AD increases risk of developing the disease (Cupples et al., 2004; Lautenschlager et al., 1996). Accumulating laboratory and neuroimaging evidence shows that pre-clinical indicators of AD are disproportionately evident among asymptomatic relatives of AD patients (Bassett et al., 2006; Foldi, Brickman, Schaefer, & Knutelska, 2003; Johnson et al., 2006; La Rue et al., 2008; Mosconi et al., 2007; van Exel et al., 2009; van Vliet et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009). Some studies reported family history interactions with the APOE genotype, whereas others reported independent family history effects, suggesting the presence of an unknown gene(s) that may be responsible. These findings suggest that asymptomatic children of persons with AD may be a particularly valuable cohort for prospective studies of preclinical AD (Jarvik et al., 2008).

Motivation and Purpose of this Study

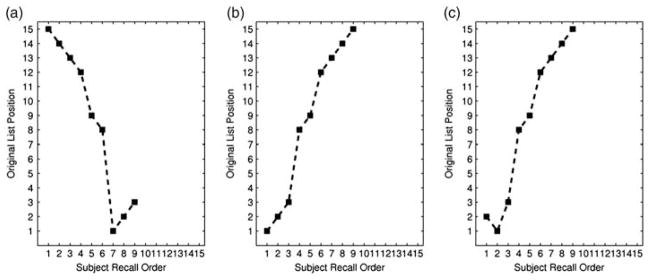

In this study, we constructed a new scoring measure to differentiate asymptomatic persons with versus without a parental family history of AD. Our motivation for developing a new measure grew from the observation that primacy and subjective organization measures are computed over discrete binnings, that is, partitions, of the word list, ignoring the actual order of recall. This is shown in Figure 1. Although the sequence of recall is opposite for 1a) and 1b), the primacy score is the same. Additionally, although recall pairs 1a) and 1b) appear less similar than recall pairs 1b) and 1c), the subjective organization scores are the same. As these examples illustrate, the order of recall provides significant information about individual differences not captured by serial position or subjective organization measures.

Fig. 1.

Examples of differences in recall order on a verbal list learning task. This figure shows the recall order on the x-axis and the original list position on the y-axis. Each subfigure has example trials that recall the same words but in different orders. 1a) and 1b) result in the same serial position scoring because order is not taken into consideration. Yet, the recall strategies seem almost opposite. The subjective organization score across 1b) and 1a) is identical to the score across 1b) and 1c). However, it seems that 1b) and 1c) are much more similar than 1a) and 1b) and should not have the same subjective organization score if order is considered. These examples highlight differences in recall strategies that are not captured by these measures.

Our long-term goal is to determine whether a machine learning framework can help identify individual patients with preclinical AD. Toward this aim, we first attempted to amplify the separation between high risk (family history of AD) and low risk (no family history of AD) populations. The main issue is whether more nuanced neuropsychological analyses that move beyond standard descriptive measures can uncover hidden signals that better separate these populations. We examine the benefits obtained from combining the pre-existing and new measures of AVLT performance to create a more informative aggregate measure. Our approach is novel in clinical neuropsychology literature as it combines methods drawn from statistics and machine learning in evaluating the psychometric testing. We demonstrate that this finer-grained analysis and concept of combining measures for AVLT data yields far greater separation between family history and control populations than traditional clinical analytic approaches.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were English-speaking middle-aged adults (40 to 65 years at baseline) enrolled in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP), a prospective longitudinal study which began in 2001 (see Sager, Hermann, & La Rue, 2005). Family-history participants (FH+) had at least one parent with autopsy-confirmed or probable AD defined by NINCDS-ADRDA criteria (McKhann et al., 1984). Control participants (FH−) had mothers surviving to at least 75 years and fathers to at least 70 years without Alzheimer’s disease, other dementia or significant memory deficits. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Procedures

Clinical measures, health history, neuropsychological testing and laboratory tests such as APOE ε4 genotyping (Athena Diagnostics, Worcester, MA and the Laboratory for Endocrinology, Aging, and Disease, William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, WI) were collected for all WRAP participants (see Sager et al., 2005, for greater detail). Multiple measures in the WRAP neuropsychological battery were reduced using factor analysis to six weighted, standardized summary scores (see Appendix A and Dowling, Hermann, La Rue, & Sager, 2010, for a description of factor procedures).

The AVLT, collected at baseline assessment, served as the primary neuropsychological measure for the present analyses. This test involves recalling 15 unrelated nouns across 5 learning trials. Repetitions or intrusions were not included in the recall sequence.

AVLT Measures

One of the most commonly reported AVLT scores is the total number of words recalled over the five learning trials. We examined two other standard AVLT measures and introduced a novel, more effective approach. To provide examples of how these measures were computed, we represented recall as a 15-element vector (i.e., ordered list). Each number represented the position in the order of presentation from the original list and the position of each element in the vector was the position in the order of recall. In other words, position one in the vector was the first word recalled while the number in that position was the word’s location in the original list. We filled in zeros at the vector positions (up to the 15th element) after the last word that was recalled. Below are two examples of recall: trial a =(1,2,3,4,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) and trial b = (8,7,4,3,1,2,6,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0). For instance, in trial b, word 8 in the original list was recalled first.

Serial position primacy

Serial position effects were calculated for the five learning trials. Primacy is defined as the proportion of the first four words from the list that were recalled (Foldi, Kneutelska, Winnick, Dahlman, & Andreeva-Cook, 2005; Hermann et al., 1996; La Rue et al., 2008). In the examples given above, the primacy score was 1.0 for both sequences. The middle region and recency were not examined because primacy was the only serial position score showing a significant family history group differences in previous analyses (La Rue et al., 2008).

Subjective organization

A paired frequency measure of subjective organization (Bousfield & Bousfield, 1966; Ramakers et al., 2008; Tulving, 1962) was used. A higher subjective organization score indicates that more word pairs are recalled together in two sequential trials. We calculated this for the first five trials (i.e., trial 1 and trial 2, trial 2 and trial 3, trial 3 and trial 4, trial 4 and trial 5), which provided four measures. (See Appendix B for examples of subjective organization calculation.)

Euclidean distance measure

A new measure to investigate AVLT recall strategy was derived from machine learning, a major subfield of computer science. One aspect of machine learning is the design of algorithms to classify new examples using previously collected data. For example, given a previously unencountered person, can we predict if they are at high risk of AD? A basic task is to select or engineer features that separate between classes of interest. This is a classic problem in machine learning and statistics known as feature selection (Guyon & Elisseeff, 2003). Creating novel features that accentuated the difference between FH+ (high risk of AD development) and FH− (low risk of AD development) was the motivation for formulating the new approach to extract data from AVLT performance.

We constructed a new measure using the Euclidean distance between trials i and i + 1 defined as:

where ti,j was position j from trial i, ti + 1,j was position j from trial i + 1. A higher Euclidean distance measure indicates greater word order variability between two recall trials. For example, the Euclidean distance between recall a and b is 10.8. (See Appendix B for Euclidean distance example calculation). We calculated the measure between sequential trials from the five learning trials, which provided four measures.1

Metric combination

We constructed a new aggregate measure:

where M̄Prim(i) was the normalized primacy score on trial i, M̄SO(j,j+1) was the normalized score of subjective organization between trials j and j + 1, and M̄Euc(k,k+1) was the normalized Euclidean distance between trials k and k + 1. Trials i, j, and k may or may not be distinct. We normalized each measure to lie in [0, 1] to eliminate arbitrary scaling differences in their scoring methodology. For example, the maximum value for primacy is 1.0, whereas the maximum Euclidean distance is approximately 41.53. The parameters for β1, β2, and β3 were set to β1 = β2 = β3 = 1 (see Appendix C for parameter selection and its validity). This yielded a measure of:

Using this method with β1 = β2 = β3 = 1 to obtain the aggregate measure, we tested all combinations of significant measures (p <.05) identified in the single measures’ analysis of variance (ANOVA). As justified in Appendix C, we chose i = 1, j = 1, and k = 3. (See Appendix B for a sample calculation). We also tested aggregate measures with only two significant measures. This included the three pairs: primacy and Euclidean measure, primacy and subjective organization, and Euclidean measure and subjective organization. The final aggregate measure chosen was:

Statistical Analysis

We examined the five trial total score (total words recalled), the primacy effect on each of the five learning trials, and the subjective organization and Euclidean measures between sequential pairs of trials from the five learning trials. Therefore, we had five measures for primacy while there were four measures for subjective organization and Euclidean measure. We calculated the mean and standard deviation in each trial for primacy and in each sequential trial pair for subjective organization and Euclidean measure. Type III sum of squares ANOVA was performed with family history, APOE ε4, age, sex, and education level as predictors and with the measures as the response variable. The same ANOVA analysis was performed with all aggregate measures. We also calculated the pairwise Pearson’s correlation coefficients of the individual measures.

Comparison of p Values in Hypothesis Testing

Although it is conceptually and mathematically difficult to compare p values derived from the same dataset using different measures, we believe it is justified in this case. As is commonly described, the p value is defined as the probability, assuming the null hypothesis is true, of observing a value of the test statistic the same as or more extreme than what is actually observed (Wasserman, 2004). The comparison of p values from the same dataset is useful only when it provides additional insight into the problem at hand (Ott & Longnecker, 2001). In other words, comparing the value of the test statistic at p = .05 and p = .0005 is only meaningful when the process by which the p value is lowered is informative. Our method allows us to understand how lower p values were obtained. Namely, it tells us how using alternative measures or aggregate measures make the hypothesis tests more or less powerful.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows characteristics of the FH+ and FH− groups. On average, family history subjects had statistically (p <.05) lower age, less college education, and more APOE ε4. Regarding cognitive factor scores, there were no significant family history group differences on verbal learning and memory, working memory, speed and flexibility, visuospatial ability, or verbal ability. The lower performance of the FH+ group on immediate memory was consistent with performance differences examined in greater detail in the current analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline neuropsychological characteristics of persons with (FH+) and without (FH−) a family history of AD

| FH+ | FH− | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age*, mean (sd) | 53.3 (6.7) | 56.3 (5.9) |

| BA/BS, % (n) | 56 (494) | 67 (238) |

| Female, % (n) | 71 (625) | 67 (238) |

| White, % (n) | 92 (809) | 93 (330) |

| APOE ε4, % (n) | 47 (417) | 20 (71) |

| Neuropsychological factor scores | ||

| Immediate memory, mean (se) | −0.05 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.05) |

| Verbal learning & memory, mean (se) | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.02 (0.05) |

| Working memory, mean (se) | 0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.05) |

| Speed & flexibility, mean (se) | 0.00 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.05) |

| Visuospatial ability, mean (se) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.05) |

| Verbal ability, mean (se) | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.04) |

Note: sd = standard deviation, BA/BS = Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Science, se = standard error.

Satterthwaite approximation used due to heteroskedasticity. Bold entries represent significant FH differences, p < .05.

Using the total words recalled over five trials, ANOVA for family history (p = .596) and APOE ε4 (p = .125) were not significant. Using the same ANOVA methods, we tested the relationship of trial-specific primacy, subjective organization or Euclidean measure with family history and APOE ε4. Table 2 shows that family history was significant for primacy trial 1 (p = .0059), subjective organization across trials 1–2 (p = .0224) and trials 3–4 (p = .0434), and the Euclidean measure across trials 3–4 (p = .00051). The Euclidean measure across trials 3–4 was most significant. In trial 1, the FH+ group showed lower primacy relative to controls and less organization in recall in the transition from trials 1 to 2. In contrast, in the transition from trials 3 to 4, FH+ participants showed higher subjective organization and lower Euclidean measure.

Table 2.

Trial-by-trial mean and significance of family history and APOE ε4 with supplementary measures

| Trial | FH+ mean (sd) | FH− mean (sd) | FH p-val | APOE p-val |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primacy | ||||

| 1 | 0.46 (0.26) | 0.50 (0.26) | .00599 | .496 |

| 2 | 0.68 (0.23) | 0.70 (0.24) | .0744 | .274 |

| 3 | 0.78 (0.22) | 0.78 (0.22) | .994 | .703 |

| 4 | 0.84 (0.19) | 0.83 (0.19) | .852 | .737 |

| 5 | 0.86 (0.19) | 0.84 (0.19) | .361 | .627 |

| Subjective organization | ||||

| 1–2 | 0.77 (1.02) | 0.90 (1.12) | .0224 | .456 |

| 2–3 | 1.55 (1.52) | 1.47 (1.53) | .407 | .498 |

| 3–4 | 2.12 (1.93) | 1.88 (1.78) | .0434 | .427 |

| 4–5 | 2.64 (2.14) | 2.49 (2.31) | .276 | .560 |

| Euclidean measure | ||||

| 1–2 | 20.02 (5.72) | 20.07 (5.72) | .604 | .912 |

| 2–3 | 19.02 (5.82) | 19.42 (6.11) | .237 | .808 |

| 3–4 | 18.26 (6.12) | 19.43 (5.84) | .00051 | .332 |

| 4–5 | 18.08 (6.80) | 18.09 (6.40) | .536 | .101 |

Note. p values are shown from type III sum of squares ANOVA for primacy, subjective organization or Euclidean measure with family history (FH), APOE ε4 status, age, sex and education level as predictors. sd = standard deviation; p-val = p value; FH = family history; APOE = apolipoprotein ε4.

The Pearson’s correlations between the significant trial-specific measures are shown in Table 3. Correlations ranged from −0.269 to 0.224 and were similar using Spearman’s non-parametric correlation (data not shown). Although some reached statistical significance, all were considered small (Cohen, 1988). These low correlations indicated that the components of the aggregate measure may reflect different cognitive processes.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation between measures at specific trials and trial pairs (95% confidence intervals)

| Trials 1–2 SO | Trials 3–4 SO | Trials 3–4 Euclidean measure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 primacy | 0.175 (0.121, 0.229) | 0.156 (0.101, 0.210) | 0.0277 (20.0281, 0.0834) |

| Trials 1–2 SO | 0.224 (0.170, 0.276) | −0.0150 (20.0708, 0.0408) | |

| Trials 3–4 SO | −0.269 (20.753, 20.216) |

Note. SO = subjective organization.

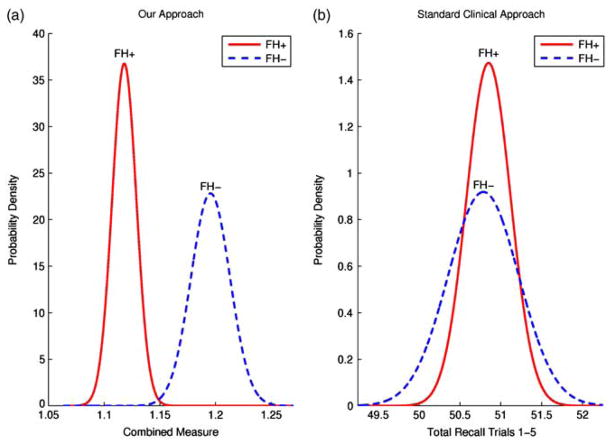

Table 4 shows ANOVA results of family history and APOE ε4 for the combination measures. We selected the significant trial-specific measures from ANOVA, which included primacy trial 1, subjective organization trials 1–2, subjective organization trials 3–4, and Euclidean measure trials 3–4. There were three combination measures with a lower p value than the single Euclidean measure across trials 3–4. These included: primacy trial 1 and Euclidean measure trials 3–4 (p = 4.92 × 10−5); subjective organization trials 1–2 and Euclidean measure trials 3–4 (p = 4.38 × 10−5); and primacy trial 1, subjective organization trials 1–2, and Euclidean measure trials 3–4 (p = 1.44 × 10−5). Figure 2 contrasts the FH+ and FH− population separation using our aggregate measure compared to a standard clinical score of the total words recalled in trials 1–5. APOE ε4 was not a significant predictor for any single or aggregate measure.

Table 4.

Measure combination ANOVA p value and effect size

| Primacy t1 | SO t1–2 | SO t3–4 | Euclidean measure t3–4 | FH p-val (effect size) | APOE p val (effect size) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | ✓ | 1.76 × 10−3 (−0.0590) | .458 (−0.0126) | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | .283 (−0.0226) | .191 (−0.0249) | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 4.92 × 10−5 (−0.0807) | .911 (−1.99 × 10−3) | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 4.38 × 10−5 (−0.0458) | .528 (6.37 × 10−3) | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | .435 (−9.41 × 10−3) | .588 (−5.90 × 10−3) | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1.44 × 10−5 (−0.0927) | .831 (−4.12 × 10−3) | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | .0112 (−0.0564) | .414 (−0.0164) |

Note: ANOVA = analysis of variance; SO = subjective organization; t = trial; FH = family history; p-val = p value; APOE = apolipoprotein ε4.

Fig. 2.

Our approach versus standard clinical approach. The FH+ and FH− population separation with our aggregate measure using primacy trial 1, subjective organization trials 1–2 and Euclidean trials 3–4 (a) is compared to the traditional clinical score and the total words recalled in trials 1–5 (b). The normal probability density function (Drake, 1967) is plotted for FH+ and FH− using maximum likelihood where the estimated mean and standard error of each population is the mean and standard deviation of the normal distribution. Even without covariate adjustment, we see the increase in FH+ and FH− population separation when using the aggregate measure as opposed to total words recalled.

DISCUSSION

The main contribution of this study is the use of a machine learning framework to derive an aggregate measure to amplify a marginally statistically significant difference between asymptomatic middle-aged children of persons with and without a parental family history of AD as seen in Figure 2. Our approach used stochastic gradient descent from machine learning to combine three weakly correlated psychometric measures. We showed that these finer-grained and supplementary measures were not redundant and were likely signals for different aspects of learning occurring at various points across the learning trials. By deconstructing and combining these measures, we obtained significantly lower p values that did not indicate overfitting and provided a more accurate preclinical signal distinguishing AD family history and control groups.

Supplementary, Fine-Grained, and Aggregate Measures

Several previous studies of serial position effects and subjective organization (La Rue et al., 2008; Ramakers et al., 2010) examined average scores across learning trials. In contrast, by analyzing results on a trial-by-trial basis, we advocate combining different testing measures to capture different phenomena along a subject’s learning curve for the AVLT, reflecting the dynamic processes occurring across trials.

We confirmed an earlier finding from the WRAP cohort that persons with a parental family history of AD showed reduced retrieval from the primacy region compared to those whose parents did not have AD (La Rue et al., 2008). However, we demonstrated that this serial position effect was significant only on the initial learning trial, with a trend toward family history group differences on trial 2. The finding that primacy differences and other serial positional effects was most pronounced on the initial trial of learning tasks was reported in some prior studies, especially for cognitively intact persons (Howieson et al., 2010), but others found distinct serial position scores on later as well as earlier trials (Carlesimo, Sabbadini, Fadda, & Caltagirone, 1997). In our study, the high performance level overall on the AVLT suggested that ceiling effects may have reduced the likelihood of finding serial position differences on later trials. As shown in Table 2, both family history and control groups recalled over 80% of items from the primacy region by trials 4 and 5.

Comparing performance across adjacent trials provided significant insight into the strategies that subjects used to learn and recall additional words, complementing information from single-trial serial position scores. The most significant family history difference was seen with the Euclidean measure at trials 3–4, which had a p value for family history an order of magnitude lower than primacy in trial 1. Although several esoteric distance functions (e.g., Smith-Waterman alignment; Durbin, Eddy, Krogh, & Mitchison, 1998) had lower p values than Euclidean distance in this comparison, we selected Euclidean distance in this study for its simplicity. When analyzed trial-by-trial, learning tasks from another study also showed strongly significant signals between later trials that did not correspond to initial assumptions about how to interpret a standard neuropsychological test (Coen et al., 2009).

We found statistically significant family history group differences in subjective organization across trials 1–2 and trials 3–4. Controls had higher subjective organization in trials 1–2 than family history subjects. This result was similar in direction to the findings of Ramakers et al. (2010), which showed higher subjective organization for MCI patients who did not progress to AD compared to those that did progress to AD. By trials 3–4, however, persons in our sample with a family history of AD showed greater subjective organization in recall than controls, and they also had a smaller Euclidean measure for this pair of trials. Although we cannot be certain how to interpret these later-trial results, one possibility is that FH+ subjects may be consolidating their gains and committing to memory the items they know best at trial 3, whereas FH− participants may still be attempting to learn additional words at that point in the learning process.

Considering all results together, persons with a family history of AD exhibited a less efficient initial approach to list learning, for example, less ability to rehearse the first-presented items, and slowness in identifying subjectively related clusters within the list. In contrast, during later learning trials, family history participants were repeating subjectively organized units more consistently than controls and were drawing recalled items from less diverse serial positions in the list. The end result was that the two groups accomplished the same total learning but arrived there in different ways.

A recent structural MRI study of persons with mild AD found that early trial responses on the AVLT were more closely correlated with brain structures involved in working memory and semantic memory processes, while later learning trials and delayed recall were associated with medial temporal lobe structures involved in episodic memory (Wolk et al., 2011). In our clinically asymptomatic sample, it is possible that the family history group differences on early learning trials may have more to do with working memory and semantic memory than with secondary memory per se. Applying a brain-behavior approach such as that of Wolk et al. (2011) to asymptomatic at-risk samples could help identify possible anatomic substrates for diverse aspects of the learning process that may change preclinically.

Having demonstrated that different weakly correlated measures were sensitive to different aspects of the learning and recall process, we used an aggregate measure to show that a simple normalized linear combination of these measures increased the statistical significance of the separation between family history and control populations. The combination with the lowest p value used all three measures on different trials. Primacy was significant on trial 1, subjective organization was significant across trials 1–2, and the Euclidean measure was significant across trials 3–4. Our approach was to find all signals in the data that distinguished the two groups.

Because we demonstrated that each individual measure contributed something new based on the statistical results when combining AVLT measures, this approach enabled a far more informative method for distinguishing populations with and without a family history of AD. This fine-grained analysis is the first step toward clarifying the role of cognitive tests such as the AVLT in identifying preclinical AD.

Family History and APOE ε4 in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease

Although our analyses showed these measures to be significantly related to family history, no measure was related to APOE ε4. A recent meta-analysis of studies of APOE effects on normal cognition (Wisdom, Callahan, & Hawkins, 2011) concluded that having an ε4 allele was associated with a modest negative influence on episodic memory but that the effect size was smaller in younger subjects and for ε4 heterozygotes as opposed to homozygotes. The WRAP sample was relatively young and only 11.7% of our APOE ε4-positive subgroup had two ε4 alleles. Ramakers et al. (2008) reported an APOE ε4-related reduction in subjective organization during AVLT recall in a middle-aged sample, but their participants were already diagnosed with MCI.

Another factor that may lead to inconsistencies in the literature on preclinical cognitive effects of APOE is the likelihood of confounding effects between ε4 positivity and family history of AD. Many studies that examined APOE effects did not report family history status of participants or analyze results in terms of family history, alone or in conjunction with APOE. However, some other investigators discussed the importance of both APOE ε4 and family history (Corder & Caskey, 2009; Hayden et al., 2009). A parental history of AD was linked to reduction in overall brain glucose metabolism (Mosconi et al., 2007), differences in BOLD signal reduction tasks (Xu et al., 2009), and a sharper trajectory of total cerebral brain volume decline in combination with APOE ε4 (Debette et al., 2009). The current findings, combined with previously reported serial position results (La Rue et al., 2008), suggest that parental family history of AD may also be linked to preclinical cognitive changes. These are subtle findings not reflected in traditional output measures of the AVLT, such as total words recalled.

Study Impact

Our results have implications both for AD research and for cognitive testing in general. Because the family history population is at increased risk of developing AD, observing enhanced differences between family history and control populations via traditional cognitive tests and a machine learning approach may help to signify a midlife indicator of preclinical AD. We believe these measures in combination with other predictors may be an integral component of predicting risk of future AD. By increasing clinical measures of separation between family history and control populations using this novel approach, it may become possible to identify individuals at risk of developing dementia who may benefit from cognitive rehabilitation (Hampstead, Sathian, Moore, Nalisnick, & Stringer, 2008; Verhaeghen, Marcoen, & Goossens, 1992) and lifestyle modifications (Barnes & Yaffe, 2011). The findings of this study are broadly applicable to neuropsychology research. In this initial study, we showed the best neuropsychological signal may not be easily developed from standard descriptive measures. Instead this signal may be derived via a combination of supplementary measures that themselves are best applied during different phases of the learning process.

There were limitations to this study. Although we hypothesized that family history and control differences may be predictive of future AD, these differences may relate to an entirely distinct phenomenon such as stable cognitive phenotypes (Greenwood, Lambert, Sunderland, & Parasuraman, 2005). Few participants in this cohort developed AD during the time period of these analyses. We plan to analyze longitudinal data as the study progresses to evaluate the association of the aggregate measures with AD development. We acknowledge our approach was data driven and was meant for exploratory analysis. Additional analysis with similar family history data-sets and datasets with differing AD risk, for example, MCI versus normal cognitive aging, must be done to confirm the significance of these methods. Furthermore, longitudinal data including disease outcome will be needed before it can be clinically useful as a predictive model.

While this study demonstrated clear benefits with respect to AVLT evaluation in particular, we believe the approach is quite general and can be applied to a variety of conventional neuropsychological tests. As such, it supports the view that more nuanced and sensitive performance measures can tell a different story about patients’ performance, and combining them can be far more informative than examining them individually.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant 1UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant 2T32GM008962 from the Medical Scientist Training Program Award program of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), NIH, and grant 5R01AG027161 from the National Institute of Aging (NIA), NIH. Additional support included the Helen Bader Foundation, Northwestern Mutual Foundation, Extendicare Foundation, Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, the Vilas Trust, and the School of Medicine and Public Health, the Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics, and the Department of Computer Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics and written informed consent was obtained from each patient (HSC #H-2006-0202 on 3/2009 and HSC #2001-329 on 11/2009). We thank Grace Wahba and Marissa Phillips for helpful discussion and are especially grateful to the WRAP participants.

APPENDIX A: BASELINE NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL BATTERY FACTOR STRUCTURE

Table A1.

Factor structure of six cognitive domains identified in the baseline neuropsychological battery

| Factor name | Cognitive test |

|---|---|

| Immediate memory |

|

| Verbal learning & memory |

|

| Working memory |

|

| Speed & flexibility |

|

| Visuospatial ability |

|

| Verbal ability |

|

APPENDIX B: AVLT MEASURE EXAMPLES

The two examples of recall in the text were: trial a = (1,2, 3,4,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0) and trial b = (8,7,4,3,1,2,6,0,0,0, 0,0,0,0,0).

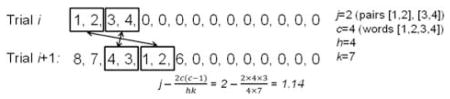

The subjective organization measure was calculated for trial i to i + 1 as j −{[2c(c−1)]/(hk)}, where j was the number of pairs of items recalled on trial i and i + 1 in adjacent positions, c was the number of common items recalled on both trials, h was the number of items recalled on trial i, and k was the number of items recalled on trial i + 1. Subjective organization between recall trial i and trial i + 1 was 1.14 and was calculated as follows:

Euclidean distance was calculated as follows:

An example calculation of the aggregate measure chosen, which used primacy trial 1, subjective organization trials 1–2 and Euclidean measure trials 3–4, is shown below. Assume a subject had the following recall for five trials.

Trial 1 = (14, 2, 12, 11, 3, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

Trial 2 = (1, 2, 14, 15, 6, 12, 8, 7, 11, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

Trial 3 = (13, 14, 9, 3, 11, 5, 6, 7, 8, 1, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0)

Trial 4 = (5, 11, 3, 1, 10, 6, 7, 9, 12, 15, 8, 4, 0, 0, 0)

Trial 5 = (12, 14, 13, 7, 6, 3, 4, 9, 2, 8, 10, 11, 5, 1, 15)

Primacy for trial 1 was 0.500; subjective organization for trials 1–2 was 0.556; and Euclidean measure for trials 3–4 was 19.6. The aggregate measure after individual measure normalization was:

APPENDIX C: AGGREGATE MEASURE

To find parameters θ = (β̄, i, j, k), we used the stochastic gradient descent method (Bertsekas & Nedic, 2003). Stochastic gradient descent is a method to identify parameters by minimizing an objective function via iterative optimization. We used θm+1 = θm−ϕ∇MAggregate(θm), where the objective function minimization was over the p value derived from an unpaired two sample t-test for FH+ and FH− using MAggregate(θm). We noticed the following interesting result. Namely, the function appeared weakly convex over a wide range of values for parameters β1, β2, and β3, all of which provided extremely similar results. We, therefore, set β1 = β2 = β3 = 1, yielding a measure of

Because there was no model parameter fitting, the results were less likely to be overfit.

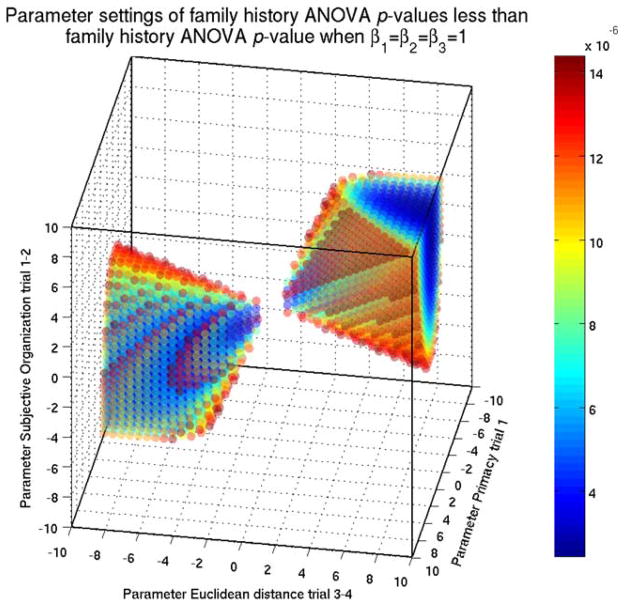

To assuage concerns of overfitting in this work, we explain that the choice of parameters in the aggregate measure M̄Prim(1) + M̄SO(1,2) + M̄Euc(3,4) had little effect on the calculated significance. Traditional machine learning approaches such as cross validation and receiver operating characteristics curves are applicable in the context of individual person predictions but are not readily applicable in the context of separating two populations. We provide evidence via a geometric argument over the parameter space. We conducted a grid search, by calculating the significance of family history in ANOVA using all triplet sets of parameters from the range [−10, 10] by a 0.5 step size. We show in Figure B1 all triplet parameters where the ANOVA family history p values are less than or equal to the p value when all parameters equal 1 (1.44 × 10−5). 11.1% of parameters would yield equal or more significant results while over 30% of parameters would yield results in concordance with those we have presented, therefore, alleviating concerns of overfitting.

Fig. B1.

We calculated the significance of family history in analysis of variance (ANOVA) using all triplet sets of parameters from the range [−10, 10] by a 0.5 step size. All triplet parameters where the ANOVA family history p values are less than or equal to the p value when all parameters equal 1 (1.44 × 10−5) are shown. The percentage of parameters that were equal or more significant was 11.07%.

Footnotes

Several more effective but esoteric distance metrics (Deza & Deza, 2009) were examined but Euclidean distance was selected for its simplicity.

References

- Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ. Cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(4):520–531. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. The Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(9):819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett SS, Yousem DM, Cristinzio C, Kusevic I, Yassa MA, Caffo BS, Zeger SL. Familial risk for Alzheimer’s disease alters fMRI activation patterns. Brain. 2006;129(5):1229–1239. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL. Neuropsychological assessment. Annual Review of Psychology. 1994;45:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45. 020194.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsekas D, Nedic A. Convex analysis and optimization. Nashua, NH: Athena Scientific; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield AK, Bousfield WA. Measurement of clustering and of sequential constancies in repeated free recall. Psychological Reports. 1966;19(3):935–942. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1966.19.3.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Alzheimer’s disease: Striatal amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary changes. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1990;49(3):215–224. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jneuropath/pages/default.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitani E, Della Sala S, Logie RH, Spinnler H. Recency, primacy, and memory: Reappraising and standardising the serial position curve. Cortex. 1992;28(3):315–342. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80143-8. Retrieved from http://www.cortexjournal.net/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Sabbadini M, Fadda L, Caltagirone C. Word-list forgetting in young and elderly subjects: Evidence for age-related decline in transferring information from transitory to permanent memory condition. Cortex. 1997;33(1):155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(97)80011-1. Retrieved from http://www.cortexjournal.net/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen MH, Selvaprakash V, Dassow AM, Prudom S, Colman R, Kemnitz J. Modeling the role of memory function in primate game play. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Amsterdam, Netherlands. 2009. pp. 2408–2413. Retrieved from http://csjarchive.cogsci.rpi.edu/proceedings/2009/papers/556/paper556.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Caskey J. Early intervention in Alzheimer disease: The importance of APOE4 plus family history. Neurology. 2009;73(24):2054–2055. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupples LA, Farrer LA, Sadovnick AD, Relkin N, White-house P, Green RC. Estimating risk curves for first-degree relatives of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: The REVEAL study. Genetics in Medicine. 2004;6(4):192–196. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000132679.92238.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debette S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Au R, Himali JJ, Pikula A, Seshadri S. Association of parental dementia with cognitive and brain MRI measures in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2009;73(24):2071–2078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling NM, Hermann B, La Rue A, Sager MA. Latent structure and factorial invariance of a neuropsychological test battery for the study of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(6):742–756. doi: 10.1037/a0020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake AW. Fundamentals of applied probability theory. New York: McGraw-Hill College; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin R, Eddy S, Krogh A, Mitchison G. Biological sequence analysis. 1. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elias MF, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Au R, White RF, D’Agostino RB. The preclinical phase of alzheimer disease: A 22-year prospective study of the Framingham Cohort. Archives of Neurology. 2000;57(6):808–813. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldi NS, Brickman AM, Schaefer LA, Knutelska ME. Distinct serial position profiles and neuropsychological measures differentiate late life depression from normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Research. 2003;120(1):71–84. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldi NS, Kneutelska ME, Winnick W, Dahlman KL, Andreeva-Cook V. What happened to their middle region? Serial position effects (SPE) in late life depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and normal elderly on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT). Poster session presented at the 33rd Annual International Neuropsychological Society Conference; St. Louis, MO. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PM, Lambert C, Sunderland T, Parasuraman R. Effects of apolipoprotein E genotype on spatial attention, working memory, and their interaction in healthy, middle-aged adults: Results from the National Institute of Mental Health’s BIOCARD study. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(2):199–211. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Thal LJ. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61(1):59–66. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon I, Elisseeff A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. The Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2003;3:1157–1182. Retrieved from http://jmlr.csail.mit.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Hampstead BM, Sathian K, Moore AB, Nalisnick C, Stringer AY. Explicit memory training leads to improved memory for face–name pairs in patients with mild cognitive impairment: Results of a pilot investigation. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14(05):883–889. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden KM, Zandi PP, West NA, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Corcoran C, Welsh-Bohmer KA. Effects of family history and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 status on cognitive decline in the absence of Alzheimer dementia: The Cache County Study. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66(11):1378–1383. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, Albert MS, Butters MA, Gao S, Knopman DS, Launer LJ, Wagster MV. The NIH Cognitive and Emotional Health Project. Report of the Critical Evaluation Study Committee. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2006;2(1):12–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Wyler A, Davies K, Christeson J, Moran M, Stroup E. The effects of human hippocampal resection on the serial position curve. Cortex. 1996;32(2):323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(96)80054-2. Retrieved from http://www.cortexjournal.net/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howieson DB, Mattek N, Seeyle AM, Dodge HH, Wasserman D, Zitzelberger T, Jeffrey K. Serial position effects in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13803395. 2010.516742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Petersen RC, Xu YC, O’Brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E. Prediction of AD with MRI-based hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 1999;52(7):1397–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1397. Retrieved from http://www.neurology.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik L, LaRue A, Blacker D, Gatz M, Kawas C, McArdle JJ, Zonderman AB. Children of persons with Alzheimer disease: What does the future hold? Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2008;22(1):6–20. doi: 10.1097/WAD. 0b013e31816653ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Schmitz TW, Trivedi MA, Ries ML, Torgerson BM, Carlsson CM, Sager MA. The influence of Alzheimer disease family history and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 on mesial temporal lobe activation. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(22):6069–6076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0959-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kawas CH, Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Morrison A, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Arenberg D. Visual memory predicts Alzheimer’s disease more than a decade before diagnosis. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1089–1093. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL. 0000055813.36504.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killiany RJ, Gomez-Isla T, Moss M, Kikinis R, Sandor T, Jolesz F, Albert MS. Use of structural magnetic resonance imaging to predict who will get Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47(4):430–439. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200004)47:4<430::AID-ANA5>3.3.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rue A, Hermann B, Jones JE, Johnson S, Asthana S, Sager MA. Effect of parental family history of Alzheimer’s disease on serial position profiles. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(4):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager NT, Cupples LA, Rao VS, Auerbach SA, Becker R, Burke J, Farrer LA. Risk of dementia among relatives of Alzheimer’s disease patients in the MIRAGE study: What is in store for the oldest old? Neurology. 1996;46(3):641–650. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.641. Retrieved from http://www.neurology.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological assessment. 4. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. Retrieved from http://www.neurology.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi L, Brys M, Switalski R, Mistur R, Glodzik L, Pirraglia E, de Leon MJ. Maternal family history of Alzheimer’s disease predisposes to reduced brain glucose metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(48):19067–19072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705036104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott RL, Longnecker MT. An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. 5. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers IH, Visser PJ, Aalten P, Bekers O, Sleegers K, van Broeckhoven CL, Verhey FR. The association between APOE genotype and memory dysfunction in subjects with mild cognitive impairment is related to age and Alzheimer pathology. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2008;26:101–108. doi: 10.1159/000144072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers IH, Visser PJ, Aalten P, Maes HL, Lansdaal HG, Meijs CJ, Verhey FR. The predictive value of memory strategies for Alzheimer’s disease in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2010;25(1):71–77. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. 2. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rey A. L’examen clinique en psychologie [The clinical examination in psychology] Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18(4):245–249. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon DA, Kemper SJ, Mortimer JA, Greiner LH, Wekstein DR, Markesbery WR. Linguistic ability in early life and cognitive function and Alzheimer’s disease in late life. Findings from the Nun Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(7):528–532. doi: 10.1001/jama. 1996.03530310034029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2011;7(3):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenerry M, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber L. Stroop neuropsychological screening test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resource; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Subjective organization in free recall of “unrelated” words. Psychological Review. 1962;69(4):344–354. doi: 10.1037/h0043150 van. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exel E, Eikelenboom P, Comijs H, Frölich M, Smit JH, Stek ML, Westendorp RG. Vascular factors and markers of inflammation in offspring with a parental history of late-onset Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):1263–1270. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet P, Westendorp RG, Eikelenboom P, Comijs HC, Frolich M, Bakker E, van Exel E. Parental history of Alzheimer disease associated with lower plasma apolipo-protein E levels. Neurology. 2009;73(9):681–687. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b59c2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Marcoen A, Goossens L. Improving memory performance in the aged through mnemonic training: A meta-analytic study. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7(2):242–251. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman L. All of statistics: A concise course in statistical inference. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh K, Butters N, Hughes J, Mohs R, Heyman A. Detection of abnormal memory decline in mild cases of Alzheimer’s disease using CERAD neuropsychological measures. Archives of Neurology. 1991;48(3):278–281. doi: 10.1001/archneur. 1991.00530150046016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. Wide range achievement test (WRAT3) administrative manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom NM, Callahan JL, Hawkins KA. The effects of apolipoprotein E on non-impaired cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk D, Dickerson B Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Fractionating verbal episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1530–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, McLaren DG, Ries ML, Fitzgerald ME, Bendlin BB, Rowley HA, Johnson SC. The influence of parental history of Alzheimer’s disease and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 on the BOLD signal during recognition memory. Brain. 2009;132(2):383–391. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ. Cognitive impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(4):520–531. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. The Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(9):819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett SS, Yousem DM, Cristinzio C, Kusevic I, Yassa MA, Caffo BS, Zeger SL. Familial risk for Alzheimer’s disease alters fMRI activation patterns. Brain. 2006;129(5):1229–1239. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL. Neuropsychological assessment. Annual Review of Psychology. 1994;45:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45. 020194.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsekas D, Nedic A. Convex analysis and optimization. Nashua, NH: Athena Scientific; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield AK, Bousfield WA. Measurement of clustering and of sequential constancies in repeated free recall. Psychological Reports. 1966;19(3):935–942. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1966.19.3.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Alzheimer’s disease: Striatal amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary changes. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1990;49(3):215–224. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jneuropath/pages/default.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitani E, Della Sala S, Logie RH, Spinnler H. Recency, primacy, and memory: Reappraising and standardising the serial position curve. Cortex. 1992;28(3):315–342. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80143-8. Retrieved from http://www.cortexjournal.net/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Sabbadini M, Fadda L, Caltagirone C. Word-list forgetting in young and elderly subjects: Evidence for age-related decline in transferring information from transitory to permanent memory condition. Cortex. 1997;33(1):155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(97)80011-1. Retrieved from http://www.cortexjournal.net/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen MH, Selvaprakash V, Dassow AM, Prudom S, Colman R, Kemnitz J. Modeling the role of memory function in primate game play. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Amsterdam, Netherlands. 2009. pp. 2408–2413. Retrieved from http://csjarchive.cogsci.rpi.edu/proceedings/2009/papers/556/paper556.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Corder EH, Caskey J. Early intervention in Alzheimer disease: The importance of APOE4 plus family history. Neurology. 2009;73(24):2054–2055. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupples LA, Farrer LA, Sadovnick AD, Relkin N, White-house P, Green RC. Estimating risk curves for first-degree relatives of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: The REVEAL study. Genetics in Medicine. 2004;6(4):192–196. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000132679.92238.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debette S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Au R, Himali JJ, Pikula A, Seshadri S. Association of parental dementia with cognitive and brain MRI measures in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2009;73(24):2071–2078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling NM, Hermann B, La Rue A, Sager MA. Latent structure and factorial invariance of a neuropsychological test battery for the study of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(6):742–756. doi: 10.1037/a0020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake AW. Fundamentals of applied probability theory. New York: McGraw-Hill College; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin R, Eddy S, Krogh A, Mitchison G. Biological sequence analysis. 1. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elias MF, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Au R, White RF, D’Agostino RB. The preclinical phase of alzheimer disease: A 22-year prospective study of the Framingham Cohort. Archives of Neurology. 2000;57(6):808–813. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldi NS, Brickman AM, Schaefer LA, Knutelska ME. Distinct serial position profiles and neuropsychological measures differentiate late life depression from normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Research. 2003;120(1):71–84. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldi NS, Kneutelska ME, Winnick W, Dahlman KL, Andreeva-Cook V. What happened to their middle region? Serial position effects (SPE) in late life depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and normal elderly on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT). Poster session presented at the 33rd Annual International Neuropsychological Society Conference; St. Louis, MO. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood PM, Lambert C, Sunderland T, Parasuraman R. Effects of apolipoprotein E genotype on spatial attention, working memory, and their interaction in healthy, middle-aged adults: Results from the National Institute of Mental Health’s BIOCARD study. Neuropsychology. 2005;19(2):199–211. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundman M, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Bennett DA, Thal LJ. Mild cognitive impairment can be distinguished from Alzheimer disease and normal aging for clinical trials. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61(1):59–66. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon I, Elisseeff A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. The Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2003;3:1157–1182. Retrieved from http://jmlr.csail.mit.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Hampstead BM, Sathian K, Moore AB, Nalisnick C, Stringer AY. Explicit memory training leads to improved memory for face–name pairs in patients with mild cognitive impairment: Results of a pilot investigation. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14(05):883–889. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden KM, Zandi PP, West NA, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Corcoran C, Welsh-Bohmer KA. Effects of family history and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 status on cognitive decline in the absence of Alzheimer dementia: The Cache County Study. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66(11):1378–1383. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrie HC, Albert MS, Butters MA, Gao S, Knopman DS, Launer LJ, Wagster MV. The NIH Cognitive and Emotional Health Project. Report of the Critical Evaluation Study Committee. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2006;2(1):12–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Wyler A, Davies K, Christeson J, Moran M, Stroup E. The effects of human hippocampal resection on the serial position curve. Cortex. 1996;32(2):323–334. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(96)80054-2. Retrieved from http://www.cortexjournal.net/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howieson DB, Mattek N, Seeyle AM, Dodge HH, Wasserman D, Zitzelberger T, Jeffrey K. Serial position effects in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13803395. 2010.516742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Petersen RC, Xu YC, O’Brien PC, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E. Prediction of AD with MRI-based hippocampal volume in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 1999;52(7):1397–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1397. Retrieved from http://www.neurology.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik L, LaRue A, Blacker D, Gatz M, Kawas C, McArdle JJ, Zonderman AB. Children of persons with Alzheimer disease: What does the future hold? Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2008;22(1):6–20. doi: 10.1097/WAD. 0b013e31816653ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Schmitz TW, Trivedi MA, Ries ML, Torgerson BM, Carlsson CM, Sager MA. The influence of Alzheimer disease family history and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 on mesial temporal lobe activation. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(22):6069–6076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0959-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kawas CH, Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, Morrison A, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Arenberg D. Visual memory predicts Alzheimer’s disease more than a decade before diagnosis. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1089–1093. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL. 0000055813.36504.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killiany RJ, Gomez-Isla T, Moss M, Kikinis R, Sandor T, Jolesz F, Albert MS. Use of structural magnetic resonance imaging to predict who will get Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47(4):430–439. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200004)47:4<430::AID-ANA5>3.3.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rue A, Hermann B, Jones JE, Johnson S, Asthana S, Sager MA. Effect of parental family history of Alzheimer’s disease on serial position profiles. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(4):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager NT, Cupples LA, Rao VS, Auerbach SA, Becker R, Burke J, Farrer LA. Risk of dementia among relatives of Alzheimer’s disease patients in the MIRAGE study: What is in store for the oldest old? Neurology. 1996;46(3):641–650. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.641. Retrieved from http://www.neurology.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological assessment. 4. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. Retrieved from http://www.neurology.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi L, Brys M, Switalski R, Mistur R, Glodzik L, Pirraglia E, de Leon MJ. Maternal family history of Alzheimer’s disease predisposes to reduced brain glucose metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(48):19067–19072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705036104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott RL, Longnecker MT. An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. 5. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers IH, Visser PJ, Aalten P, Bekers O, Sleegers K, van Broeckhoven CL, Verhey FR. The association between APOE genotype and memory dysfunction in subjects with mild cognitive impairment is related to age and Alzheimer pathology. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2008;26:101–108. doi: 10.1159/000144072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers IH, Visser PJ, Aalten P, Maes HL, Lansdaal HG, Meijs CJ, Verhey FR. The predictive value of memory strategies for Alzheimer’s disease in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2010;25(1):71–77. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. 2. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rey A. L’examen clinique en psychologie [The clinical examination in psychology] Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18(4):245–249. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon DA, Kemper SJ, Mortimer JA, Greiner LH, Wekstein DR, Markesbery WR. Linguistic ability in early life and cognitive function and Alzheimer’s disease in late life. Findings from the Nun Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(7):528–532. doi: 10.1001/jama. 1996.03530310034029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2011;7(3):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenerry M, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber L. Stroop neuropsychological screening test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resource; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Subjective organization in free recall of “unrelated” words. Psychological Review. 1962;69(4):344–354. doi: 10.1037/h0043150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Exel E, Eikelenboom P, Comijs H, Frölich M, Smit JH, Stek ML, Westendorp RG. Vascular factors and markers of inflammation in offspring with a parental history of late-onset Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):1263–1270. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry. 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet P, Westendorp RG, Eikelenboom P, Comijs HC, Frolich M, Bakker E, van Exel E. Parental history of Alzheimer disease associated with lower plasma apolipo-protein E levels. Neurology. 2009;73(9):681–687. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b59c2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Marcoen A, Goossens L. Improving memory performance in the aged through mnemonic training: A meta-analytic study. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7(2):242–251. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman L. All of statistics: A concise course in statistical inference. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh K, Butters N, Hughes J, Mohs R, Heyman A. Detection of abnormal memory decline in mild cases of Alzheimer’s disease using CERAD neuropsychological measures. Archives of Neurology. 1991;48(3):278–281. doi: 10.1001/archneur. 1991.00530150046016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. Wide range achievement test (WRAT3) administrative manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom NM, Callahan JL, Hawkins KA. The effects of apolipoprotein E on non-impaired cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis. Neurobiology of Aging. 2011;32(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk D, Dickerson B Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Fractionating verbal episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1530–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, McLaren DG, Ries ML, Fitzgerald ME, Bendlin BB, Rowley HA, Johnson SC. The influence of parental history of Alzheimer’s disease and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 on the BOLD signal during recognition memory. Brain. 2009;132(2):383–391. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]