Abstract

Background

Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) may have delayed septal activation and left ventricular (LV) mechanical dyssynchrony, and may improve after alcohol septal ablation (ASA). This study used phase analysis of gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) to evaluate septal activation and LV dyssynchrony in HCM patients pre- and post-ASA.

Methods

Phase analysis was applied to 28 controls, and 32 HCM patients having rest MPI pre- and post-ASA to assess septal-lateral mechanical activation delay (SLD) and consequent LV dyssynchrony. In addition, phase analysis was applied to another group of 30 patients having serial MPI to measure variability of the LV dyssynchrony parameters on serial studies.

Results

ASA significantly reduced SLD and improved LV synchrony in the HCM patients with SLD<0° due to earlier activation of the lateral wall relative to the septum. Based on the measured variability, 12 HCM patients had significant (Z<−1.65, p<0.05) and 4 had moderate (Z<−1.00, p<0.15) improvement in LV synchrony post-ASA. SLD<0° predicted improvement in LV synchrony after ASA with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 88%.

Conclusion

SLD and LV dyssynchrony were frequent in HCM patients. HCM patients, whose septal activation became later than lateral activation, had significant reduction in septal activation delay and improvement in LV synchrony after ASA.

Keywords: LV Dyssynchrony, Gated SPECT, Myocardial Perfusion Imaging, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Alcohol Septal Ablation

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary myocardial disorder characterized by marked left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, which often disproportionately involves the septum [1-3]. Approximately one third of the patients with HCM have dynamic LV outflow obstruction at rest [3-4]. Recent data have confirmed that LV outflow obstruction at rest is an important determinant of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in these patients [5-8]. Alcohol septal ablation (ASA) has emerged as an alternative approach to surgical myomectomy and to medical therapy in treating symptomatic patients with HCM who have LV outflow tract obstruction [9-11]. The principles surrounding the role of outflow obstruction in HCM are supported by the current American College of Cardiology / European Society of Cardiology expert consensus recommendations [12-13].

In patients with HCM and disproportional septal hypertrophy, alteration in mechanical activation of the septum might produce LV mechanical dyssynchrony. ASA by decreasing the septal thickness might restore mechanical synchrony.

Phase analysis has been used to measure LV mechanical dyssynchrony from gated single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) [14]. This technique utilizes the partial volume effect, which states that the variation of regional maximum counts during a cardiac cycle is proportional to myocardial wall thickening of the same region. By approximating the wall-thickening curve of each myocardial region of the LV, phase analysis calculates a phase angle for each region to represent regional onset of mechanical contraction. It then assesses the heterogeneity of the phase angles over the entire LV to quantify global LV mechanical dyssynchrony and compares the phase angles among various regions to quantify regional LV mechanical dyssynchrony. Phase analysis has been shown to correlate well with two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography in measuring LV mechanical dyssynchrony [15-16] and to predict response to cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) in heart failure patients [17]. Further, a recent study showed that phase analysis could assess regional activation delay and identify the site of latest mechanical activation as the optimal site for LV pacing lead in patients undergoing CRT [18].

The purpose of this study was to use phase analysis of gated SPECT MPI to assess the effect of ASA on septal activation delay and LV mechanical dyssynchrony in patients with HCM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Three groups of patients were included in this study. The HCM group included 32 patients from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The control group included 28 normal subjects from Emory University. The repeatability group included 30 patients who had 2 serial gated SPECT MPI studies at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The baseline characteristics of these patient groups are summarized in Table 1. Emory University served as the core laboratory for image analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at all participating institutions.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| Variables | HCM Group (N=32) |

Control Group (N=28) |

Repeatability Group (N=30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53 ± 13 | 57 ± 12 | 63 ± 12 |

| Female gender | 17 (53%) | 18 (64%) | 11 (37%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 (19%) | None | 12 (40%) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1 (3%) | None | None |

| Heart Failure | 32 (100%) | None | 1 (3%) |

| LV hypertrophy by echo | 32 (100%) | None | None |

| LVEF by echo ≥55% | 32 (100%) | 28 (100%) | 27 (90%) |

Patients with HCM underwent ASA because of severe symptoms despite adequate medical therapy and all had LV outflow gradients. There were 15 men and 17 women, aged 53±13 years. The inclusion criteria were previously reported [19]. The patients underwent rest gated SPECT MPI, 4±10 days (1~30 days) before and 14±9 weeks (6~36 weeks) after ASA. The demographics in these patients were previously described in details [19]. The method of ASA was previously reported, and pressure gradients across the LV outflow tract were reported before and after the procedure, both at rest and with provocation [19].

The control group was selected from the Emory Clinical Data Warehouse provided by Emory Healthcare Information Services. Emory Clinical Data Warehouse is a central repository of historical data for all entities of Emory Healthcare from 1994 to the present. The data is generally extracted from Emory operational systems nightly then transformed into a usable format. Twenty-eight consecutive normal subjects, who had gated SPECT MPI and echocardiography within 3 months between January 2009 and October 2010, were enrolled to assess the normal pattern of septal activation. These normal subjects had no functional abnormalities such as LV dysfunction by echocardiography, heart failure symptoms, known cardiomyopathy, left-bundle branch block (LBBB), right-bundle branch block (RBBB), or LV hypertrophy and had a low likelihood of coronary artery disease (CAD).

The repeatability group consisted of 30 patients referred for clinically indicated stress testing to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who consented to participate in a study evaluating the repeatability of measurements on two serial gated SPECT MPI. The average age was 63±12 years and 19 (63%) were men. The primary indication for stress testing was pre-operative cardiovascular evaluation in 12 (40%), chest pains in 9 (30%), exertional dyspnea in 5 (17%), and evaluation of known CAD in 2 (7%), syncope in 1 (3%), and congestive heart failure in 1 (3%). Twelve patients (40%) had abnormal perfusion on SPECT. The mean summed stress score was 10.5±8.1 (range 3 to 30). The resting electrocardiogram showed LBBB, RBBB, and right ventricular paced rhythm in 1, 2, and 3 patients, respectively.

Gated SPECT MPI

Table 2 summarizes the gated SPECT MPI acquisition protocols of the three patient groups. In the HCM group, rest gated SPECT MPI studies were acquired with a dual-head detector (Philips Medical Systems, Milpitas, California) 60 minutes after intravenous injection of 15-30 mCi (555-1110 MBq) of Tc-99m sestamibi. The images were obtained in 32 projections (30 seconds per projection) using 180° anterior elliptical arc (45° right anterior oblique to 45° left posterior oblique) with 20% energy window centered on 140 keV. The RR cycle was divided into 8 or 16 frames, and gating was done with a ±50% window. The method was previously described and no stress studies were obtained [19]. The control group had standard same-day Tc-99m rest/stress MPI at Emory University Hospital. Only the resting gated MPI data were analyzed in this study. In the resting protocol, radiopharmaceutical was injected at rest at time zero with 10 mCi (370 MBq) for patients up to 200 lbs (91 kg), 12 mCi (444 MBq) for patients between 200 lbs (91 kg) and 300 lbs (136 kg), and 15 mCi (555 MBq) for patients heavier than 300 lbs (136 kg), respectively. After 60 minutes, the patient was positioned supine for SPECT acquisition using a GE Millennium MG system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). The images were acquired over an 180° collection arc beginning at 45° right anterior oblique and ending at 45° left posterior oblique with 64 projections, 30 seconds per projection. Matrix size was 64 × 64 with 8 frames/cycle. The scan was acquired using a dual-head SPECT system equipped with a low-energy high-resolution parallel-hole collimator. In the repeatability group, the patients underwent same-day, rest-stress Tc-99m sestamibi gated SPECT MPI on a dual headed camera (Philips Medical Systems, Milpitas, California) using standard imaging acquisition parameters (step and shoot format with 25 seconds per each of 64 stops, 180° orbit, and low-energy-high-resolution collimators) and 16-bin gating. Thirty minutes after the first post-stress acquisition, patients were re-positioned on the table by a separate technologist, and a gated SPECT MPI image re-acquired.

Table 2.

Acquisition Parameters of the Study Population

| Acquisition Parameters | HCM Group (N=32) |

Control Group (N=28) |

Repeatability Group (N=30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | 15-30 mCi (555-1110 MBq) |

10-15 mCi (370-555 MBq) |

30 mCi (1110 MBq) |

| Radiopharmaceutical | Tc-99m MIBI | Tc-99m MIBI | Tc-99m MIBI |

| Acquisition time post injection | 60 min | 60 min | 60 min |

| Stress or rest | Rest | Rest | Post-stress |

| Matrix size | 64×64 | 64×64 | 64×64 |

| Orbit | 180° | 180° | 180° |

| Number of projections | 32 | 64 | 64 |

| Acquisition duration | 30 s/projection | 20 s/projection | 25 s/projection |

| Gating frames | 8 or 16 | 8 | 16 |

Image Processing

Emory University Nuclear Cardiology R&D lab served as the core lab for this study. All patient studies were sent to Emory for image processing and analysis. Three different operators, who were blinded from one another, processed the images of the three groups, respectively, using the same processing parameters. All groups were reconstructed by ordered subsets expectation maximization with 3 iterations and 10 subsets. A Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.35 cycles/cm and a power of 10 was used to filter the gated images. The reconstructed images were reoriented manually to generate gated short-axis images, and then submitted to the phase analysis. For the HCM and repeatability groups, the serial images of each patient were processed side-by-side.

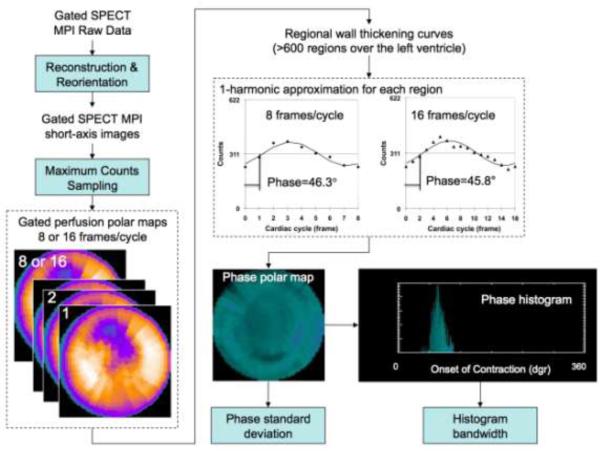

Global and Regional Dyssynchrony by Phase Analysis

Figure 1 demonstrates the processing steps of phase analysis to assess LV global dyssynchrony. The gated SPECT MPI raw data were reconstructed and reoriented using the standard protocol to generate a gated SPECT MPI short-axis image. Regional maximal count detection was performed on the gated SPECT MPI short-axis image in 3D for each temporal frame to generate wall-thickening curves for over 600 LV regions. The wall-thickening curve for each region was approximated by the 1-harmonic Fourier function to calculate a phase angle that represented the regional onset of mechanical contraction (OMC). Once the OMC phase angles of all regions were obtained, an OMC phase distribution was generated and displayed as a polar map and a histogram. The standard deviation of the OMC phase distribution (phase standard deviation, [PSD]) and the phase histogram bandwidth (PHB) (including 95% of the phase angles over the entire LV) indicated the degree of LV global dyssynchrony [14]. It must be noted that these processing steps were largely automated; therefore, phase analysis has been shown to have excellent reproducibility and repeatability in measuring LV dyssynchrony [20-21].

Figure 1.

Processing steps of phase analysis. The gated SPECT MPI raw data were reconstructed and reoriented using the standard protocol to generate a gated SPECT MPI short-axis image. Regional maximal count detection was performed on the gated SPECT MPI short-axis image in 3D for each temporal frame to generate wall-thickening curves for over 600 LV regions. The wall-thickening curve for each region was approximated by the 1-harmonic function to calculate a phase angle that represented the regional onset of mechanical contraction (OMC). Once the OMC phase angles of all regions were obtained, an OMC phase distribution was generated and displayed as a polar map and a histogram. The standard deviation of the OMC phase distribution (phase standard deviation) and the histogram bandwidth (including 95% of the phase angles over the entire LV) indicated the degree of global LV dyssynchrony.

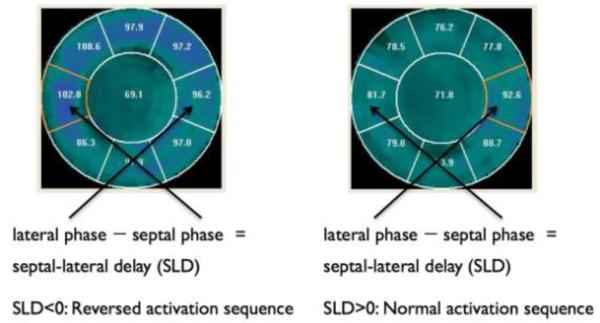

Figure 2 demonstrates the use of phase analysis to assess LV regional activation and to calculate septal-lateral wall delay (SLD). A 9-segment model was used to automatically segment the phase polar map as shown in Figure 2. The mean phase angles were automatically calculated for each segment to represent the relative regional activation time. The SLD was calculated as the difference between the mean phases of the septal and lateral segments. For a normal subject, the septal segment is activated earlier than the lateral wall; therefore, SLD is >0°.

Figure 2.

LV regional activation as assessed by phase analysis of gated SPECT MPI. A 9-segment model was used to automatically segment the phase polar map as shown in the figure. The mean phase angles were automatically calculated for each segment to represent the relative regional activation time. Septal-lateral delay (SLD) was calculated as the difference between the mean phases of the septal and lateral segments. For a normal subject, the septal segment should be activated earlier than the lateral wall, and thus, SLD should be greater than 0.

Statistical Analysis

PSD and PHB were compared between the serial gated SPECT MPI scans in the repeatability cohort (N=30) using the paired t test and Pearson’s correlation analysis. The differences in PSD and PHB between the serial gated SPECT MPI scans were expected to be normally distributed around 0°. Therefore, the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of the differences in these parameters should represent the measurement variability. Once and were determined, changes in LV dyssynchrony on serial gated SPECT MPI scans in any particular patient can be evaluated by one-sample z test as follows.

| (1) |

Where x is the difference in PSD or PHB of the patient between the two serial scans.

PSD and PHB were calculated for each patient in the HCM group pre- and post-ASA. According to the differences between pre- and post-ASA LV dyssynchrony, the HCM group was classified into two subsets: an “improved” subset with z ≤ −1.00 (p ≤ 0.15) for either PSD or PHB, and a “non-improved” subset with z > −1.00 for both PSD and PHB. Baseline LV global (PSD and PHB) and regional (SLD) dyssynchrony were compared among the two subsets and the control group using unpaired t test with unequal variance. In addition, a 2×2 table was used to analyze whether reverse septal-lateral wall activation, characterized by SLD < 0°, predicted the improvement in LV synchrony post-ASA in the HCM group.

RESULTS

The LV outflow gradient decreased from 51±38 mmHg before ASA to 7±10 mmHg after ASA (p=0.0001). Before ASA, 14 patients (44%) had ECG evidence of LV hypertrophy, and 3 patients (9%) had pacemakers. After ASA, 23 patients (72%) developed RBBB, 2 patients (6%) developed LBBB, and 11 patients (34%) required pacemaker. The perfusion defect size (involving the basal anteroseptal region) measured 7.3±6.1% of LV myocardium (by polar maps). All patients reported improvement in their symptoms after ASA.

Table 3 shows PSD and PHB measured in the repeatability cohort (N=30). Paired t test showed no significant difference between the two serial studies, demonstrating the excellent repeatability of measuring LV dyssynchrony by phase analysis of gated SPECT MPI.

Table 3.

Differences in LV dyssynchrony parameters between serial gated myocardial perfusion SPECT studies

| N=30 | PSD | PHB |

|---|---|---|

| μ | −0.1° | −0.5° |

| σ | 2.6° | 8.4° |

| p | 0.903 | 0.747 |

| r | 0.936 | 0.922 |

PSD = phase standard deviation, PHB = phase histogram bandwidth

μ = mean absolute difference, σ = standard deviation of the absolute difference, p<0.05 = statistical significance by paired t test, r = correlation coefficient

There were no significant differences in the LV dyssynchrony parameters between pre- and post-ASA in the entire HCM cohort (N=32) (PSD: 14.8° ± 6.5° vs. 12.8° ± 6.1°, p = 0.149; PHB: 46.2° ± 6.2° vs. 41.7° ± 19.5°, p = 0.233). However, 12 HCM patients showed significant (z ≤ −1.65, p ≤ 0.05 for either PSD or PHB) and 4 HCM patients showed moderate (−1.65 < z ≤ −1.00, p ≤ 0.15 for either PSD or PHB) improvement in LV synchrony post-ASA. These patients were classified as the “improved” group, whereas the other 16 HCM patients were classified as the “non-improved” group.

Table 4 shows the baseline PSD, PHB, and SLD in the “improved” and “non-improved” groups and in the control cohort. The “improved” group had significantly more septal activation delay and LV dyssynchrony at baseline, as compared to the “non-improved” group as well as the control group. The outflow gradient by Doppler 2D echocardiography at 3 months was 18.6±7.6 mmHg in the improved group and 24.2±26.4 mmHg in the non-improved group (p=0.415)

Table 4.

Baseline Septal Activation and LV Synchrony in the Control and HCM Cohorts.

| Controls (N=30) |

HCM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved (N=16) | Non-improved (N=16) |

P (Improved vs. Non-improved |

||

| PSD (°) | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 18.5 ± 6.3 * | 11.1 ± 4.4 | < 0.001 |

| PHB (°) | 26.8 ± 8.2 | 55.3 ± 13.8 * | 37.1 ± 13.2 | < 0.001 |

| SLD (°) | 7.2 ± 4.1 | −6.7 ± 11.8 * | 7.7 ± 12.0 | 0.002 |

PSD: Phase standard deviation

PHB: Phase histogram bandwidth

SLD: Septal-lateral delay

P: P values were calculated by unpaired t test with unequal variance.

P<0.05 when comparing the HCM groups and controls by unpaired t test with unequal variance.

Table 5 shows the performance of septal activation delay in predicting the improvement in LV synchrony post-ASA in the HCM cohort. Reverse septal-lateral wall activation, characterized by SLD <0°, predicted improvement in LV synchrony post-ASA with a sensitivity of 81%, a specificity of 88%, and a positive predictive value of 87% and a negative predictive value of 82%.

Table 5.

Septal-lateral Delay (SLD) in Predicting Changes in LV Synchrony post-ASA in the HCM Cohort

| Improved in LV Synchrony post-ASA |

Not Improved in LV Synchrony post-ASA |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SLD < 0° | 13 | 2 | PPV = 86.7% |

| SLD > 0° | 3 | 14 | NPV = 82.4% |

| SENS = 81.3% | SPEC = 87.5% |

SLD: Septal-lateral delay

SENS: Sensitivity

SPEC: Specificity

PPV: Positive predictive value

NPV: Negative predictive value

Table 6 shows the effect of ASA on septal activation and LV synchrony in the HCM cohort. Seventeen patients had reverse septal-lateral wall delay (SLD < 0°). In these patients, ASA significantly reduced the septal activation delay and improved LV synchrony (p<0.001).

Table 6.

Effect of ASA on Septal Activation and LV Synchrony in the HCM Patients

| HCM w/ SLD<0° (N=15) | HCM w/ SLD≥0° (N=17) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ASA | Post-ASA | P | Pre-ASA | Post-ASA | P | |

| PSD (°) | 17.5 ± 7.1 | 10.5 ± 4.9 | < 0.001 | 12.1 ± 4.6 | 14.8 ± 6.5 | 0.079 |

| PHB (°) | 52.4 ± 15.9 | 36.0 ± 14.3 | < 0.001 | 40.7 ± 14.8 | 46.6 ± 22.3 | 0.243 |

| SLD (°) | −10.5 ± 9.2 | −0.9 ± 10.7 | < 0.001 | 10.2 ± 9.1 | 3.2 ± 16.2 | 0.159 |

PSD: Phase standard deviation

PHB: Phase histogram bandwidth

SLD: Septal-lateral delay

P: P values were calculated by comparing pre- and post-ASA values by paired t test.

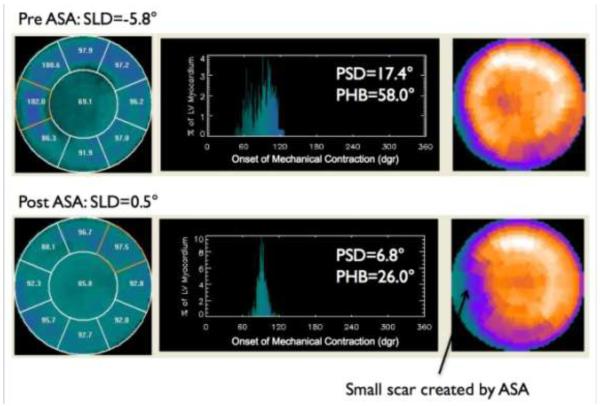

Figure 3 shows an example HCM patient. At baseline the patient had reverse septal-lateral wall activation and significant LV dyssynchrony. ASA reduced the septal activation delay and improved LV dyssynchrony.

Figure 3.

Patient example. At baseline the patient had reversed septal-lateral activation and significant LV dyssynchrony. ASA reduced the septal activation delay and improved LV dyssynchrony.

DISCUSSION

This study, using phase analysis of gated SPECT MPI, showed that septal activation delay and LV mechanical dyssynchrony were frequent in HCM patients. The LV dyssynchrony improved after ASA in the subset of patients with HCM who had septal activation delay and LV mechanical dyssynchrony at baseline. Most importantly, reverse septal-lateral wall activation predicted improvement in septal-lateral wall activation and LV synchrony following ASA with a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value >80%.

The prognostic value of LV outflow obstruction in patients with HCM is modest and controversial [13]. The relationship between LV outflow gradient at rest and the risk for sudden cardiac death is not sufficiently strong to establish LV outflow obstruction as an independent risk factor or justify decisions for implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) [22]. Right ventricular or dual chamber pacing was at one time considered a therapeutic option, conceivably by creating dyssynchrony and thereby decreasing gradient. Single-center studies have shown that dual-chamber pacing reduced LV outflow obstruction and relieved symptoms refractory to maximal medical management [23-27]. However, randomized double-blind cross-over studies could not confirm these findings and reduction in the pressure gradient was both inconsistent and generally modest [26-27].

A study using two-dimensional speckle tracking imaging showed that LV mechanical dyssynchrony was more severe in patients with HCM than in patients with hypertensive LV hypertrophy [28]. Another study using pulsed Doppler myocardial imaging showed that LV dyssynchrony was strongly related to increased septal thickness and LV outflow gradient in patients with HCM. This study also showed that severe LV dyssynchrony (intraventricular systolic delay > 45 msec) identified a subgroup of HCM patients with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia during Holter monitoring with 91% sensitivity and 96% specificity [29]. These studies support that LV mechanical dyssynchrony may be another important parameter for characterization of HCM patients and may provide valuable information for risk stratification. In addition, LV mechanical dyssynchrony as assessed by tissue Doppler imaging has been extensively studied in patients with heart failure and shown to predict patient response to CRT [30-31]. It must be noted that reliable TDI measurements require expertise to obtain reproducible results. Due to high intra-observer and inter-observer variability, the Predictors of Response to Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (PROSPECT) trial found that under “real-world” conditions the current available echocardiographic techniques are not ready for routine practice to clinically assess LV mechanical dyssynchrony and predict CRT responses in patients with heart failure [32]. On the contrary, the technique used in our study, phase analysis of gated SPECT MPI, has been shown to have excellent reproducibility and repeatability in assessing LV mechanical dyssynchrony [20-21].

The clinical implications of our study are not clear as longer follow-up of clinical status and gradient measurements at rest and provocation are not available, although on short-term bases the patients showed symptomatic improvement. The relation of baseline dyssynchrony and SLD and their changes after ASA to the risk of serious ventricular arrythmias and sudden death requires further studies and in a larger number of patients. We had previously reported that the perfusion defect size tends to decrease late after ASA compared to the size early after ASA [19].

This is the first study that evaluated LV dyssynchrony and septal activation sequence before and after ASA in patients with HCM. This observational study may help further work in this area, specifically the relation between scar size to changes in synchrony and the impact of dyssynchrony on outcome, especially serious ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death.

CONCLUSION

Septal activation delay and LV dyssynchrony, as assessed by phase analysis of gated SPECT MPI, were frequent in HCM patients. HCM patients, whose septal activation became later than lateral activation, had significant reduction in septal activation delay and improvement LV synchrony after ASA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by an NIH grant (1R01HL094438; PI: Ji Chen, PhD).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement Chen and Garcia receive royalties from the sale of the Emory Cardiac Toolbox with SyncTool. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest practice.

REFERENCES

- [1].Wigle ED, Rakowski H, Kimball BP, Williams WG. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clinical spectrum and treatment. Circulation. 1995;92:1680–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Spirito P, Seidman CE, McKenna WJ, Maron BJ. The management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:775–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1308–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Maron MS, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, et al. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:295–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Maron BJ, Maron MS, Wigle ED, Braunwald E. The 50-year history, controversy, and clinical implications of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Autore C, Bernabo P, Barilla CS, Bruzzi P, Spirito P. The prognostic importance of left ventricular outflow obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy varies in relation to the severity of symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1078–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Tome MT, et al. Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1933–41. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Long term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McLeod CJ, Ommen SR, Ackerman MJ, et al. Surgical septal myectomy decreases the risk for appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator discharge in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2583–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maron MS, Olivotto I, Zenovich AG, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is predominantly a disease of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2006;114:2232–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maron BJ. Controversies in cardiovascular medicine. Is septal ablation preferable to surgical myomectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? Surgical myectomy remains the primary treatment option for severely symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2007;116:196–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gietzen FH, Leuner CJ, Obergassel L, Strunk-Mueller C, Kuhn H. Role of transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, New York Heart Association functional class III or IV, and outflow obstruction only under provocable conditions. Circulation. 2002;106:454–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022845.80802.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Maron BJ, McKenna WJ, Danielson GK, et al. American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology clinical expert consensus document on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1687–713. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen J, Garcia EV, Folks RD, Cooke CD, Faber TL, Tauxe EL, Iskandrian AE. Onset of left ventricular mechanical contraction as determined by phase analysis of ECG-gated myocardial perfusion SPECT imaging: Development of a diagnostic tool for assessment of cardiac mechanical dyssynchrony. J Nucl Cardiol. 2005;12:687–95. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2005.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Henneman MM, Chen J, Ypenburg C, Dibbets P, Stokkel M, van der Wall EE, Garcia EV, Bax JJ. Phase analysis of gated myocardial perfusion SPECT compared to tissue Doppler imaging for the assessment of left ventricular dyssynchrony. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1708–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Marsan NA, Henneman MM, Chen J, Ypenburg C, Dibbets P, Ghio S, Bleeker GB, Stokkel MP, van der Wall EE, Tavazzi L, Garcia EV, Bax JJ. Left ventricular dyssynchrony assessed by two 3-dimensional imaging modalities: phase analysis of gated myocardial perfusion SPECT and tri-plane tissue Doppler imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:166–73. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Henneman MM, Chen J, Dibbets P, Stokkel M, Bleeker GB, Ypenburg C, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ, Garcia EV, Bax JJ. Can LV dyssynchrony as assessed with phase analysis on gated myocardial perfusion SPECT predict response to CRT? J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1104–11. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Boogers MJ, Chen J, van Bommel RJ, Borleffs CJW, Dibbets-Schneider P, van der Heil B, Younis IA, Schalij MJ, van der Wall EE, Garcia EV, Bax JJ. Optimal left ventricular lead position assessed with phase analysis on gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:230–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aqel RA, Hage FG, Zohgbi GJ, Tabereaux PB, Lawson D, Heo J, Perry G, Epstein AE, Dell’ Italia LJ, Iskandrian AE. Serial evaluations of myocardial infarct size after alcohol septal ablation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and effect of the changes on clinical status and left ventricular outflow pressure gradients. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Trimble MA, Velazquez EJ, Adams GL, Honeycutt EF, Pagnanelli RA, Barnhart HX, Chen J, Iskandrian AE, Garcia EV, Borges-Neto S. Repeatability and reproducibility of phase analysis of gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging used to quantify cardiac dyssynchrony. Nucl Med Commun. 2008;29:374–81. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3282f81380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lin X, Xu H, Zhao X, Folks RD, Faber TL, Garcia EV, Chen J. Repeatability of left ventricular dyssynchrony and function parameters in serial gated myocardial perfusion SPECT studies. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:811–6. doi: 10.1007/s12350-010-9238-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Maron MS. The dilemma of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and sudden death in hypertrophic cardio- myopathy: do patients with gradients really deserve prophylactic defibrillators (editorial)? Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1895–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Slade AKB, Sadoul N, Shapiro L, et al. DDD pacing in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a multicentre clinical experience. Heart. 1996;75:44–9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fananapazir L, Epstein ND, Curiel RV, Panza JA, Tripodi D, McAreavey D. Long-term results of dual-chamber (DDD) pacing in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Evidence for progressive symptomatic and hemodynamic improvement and reduction of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1994;90:2731–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kappenberger L, Linde C, Daubert C, et al. Pacing in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. A randomized crossover study. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1249–56. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nishimura RA, Trusty JM, Hayes DL, et al. Dual-chamber pacing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized, double-blind cross-over study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:435–41. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Maron BJ, Nishimura RA, McKenna WJ, Rakowski H, Josephson ME, Kieval RS. Assessment of permanent dual-chamber pacing as a treatment for drug-refractory symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized, double-blind cross-over study (M-PATHY) Circulation. 1999;99:2927–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.22.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nagakura T, Takeuchi M, Yoshitani H, Nakai H, Nishikage T, Kokumai M, Otani S, Yoshiyama M, Yoshikawa J. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is associated with more severe left ventricular dyssynchrony than is hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography. 2007;24:677–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].D’Andrea A, Caso P, Severino S, di Uccio F Scotto, Vigorito F, Ascione L, Scherillo M, Calabro R. Association between intraventricular myocardial systolic dyssynchrony and ventricular arrhythmias in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography. 2005;22:571–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2005.40073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bax JJ, Bleeker GB, Marwick TH, et al. Left ventricular dyssynchrony predicts response and prognosis after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1834–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bax JJ, Marwick TH, Molhoek SG, et al. Left ventricular dyssynchrony predicts benefit of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with end-stage heart failure before pacemaker implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1238–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chung ES, Leon AR, Tavazzi L, et al. Results of the Predictors of Response to CRT (PROSPECT) trial. Circulation. 2008;117:2608–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]