Abstract

Purinergic receptors have been found to modulate ion transport in several types of epithelial cells as well as excitable cells. It was of interest to determine whether vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells contain purinergic receptors in either the apicalor basolateral membrane which modulate transepithelial ion transport. Vestibular dark cell and strial marginal cell epithelia were mounted in a micro-Ussing chamber for the measurement of the transepithelial voltage and resistance from which the equivalent short circuit current (Isc) was obtained. The apical and basolateral sides were independently perfused with adenosine and adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP). Adenosine (10−5 M) had no effect on Isc at either the apical or basolateral side of vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells, suggesting either the absence of P1 receptors or the absence of coupling of P1 receptors to vectorial ion transport by these epithelia. Apical perfusion of ATP (10−8 to 10−4 M) caused a decrease in Isc of both vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells. Apical perfusion of the nucleotides uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP), 2-methylthioadenosine triphosphate (2-meS-ATP), adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (ATPγS) and α,β-methylene adenosine 5′-triphosphate (α,β-meth-ATP) caused qualitatively similar responses with different magnitudes of response. The sequence of the magnitude of response of each compound at 10−6 or 10−5 M was assessed from the fractional change of Isc. The sequence for vestibular dark cells was UTP = ATP = ATPγS ≫ 2-meS-ATP > α,β-meth-ATP, and for strial marginal cells it was UTP = ATP ≫ 2-meS-ATP, corresponding to the sequence for the P2U receptor. The effect of agonist on the apical membrane was reduced by the antagonist 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) but not cibacron blue or suramin. DIDS in the absence of exogenous purinergic agonist caused a sustained increase in Isc. The effect of ATP on the apical membrane was greater in the absence of divalent cations. Basolateral perfusion of ATP led to a biphasic response of Isc in vestibular dark cell and strial marginal cell epithelia, consisting of an initial rapid increase followed by a slower decrease. Perfusion of the perilymphatic surface of the stria vascularis (basal cell layer) with ATP had no acute effect on Isc. The initial increase of Isc in vestibular dark cell epithelium during basolateral perfusion had a sequence of 2-meS-ATP > ATP ≫ UTP = α,β-meth-ATP = ATPγS, corresponding to the sequence for the P2Y receptor. Subsequently, the agonists caused a sustained decrease in Isc with a sequence of ATPγS > 2-meS-ATP > ATP > UTP >α,β-meth-ATP. This sequence is most simply interpreted as the result of the coexistence of P2U and P2Y receptors in the basolateral membrane. Both the increase and decrease of Isc by ATP at the basolateral membrane were reduced by the antagonist suramin. These findings provide evidence for the regulation of transepithelial ion transport by P2U receptors in the apical membrane and by coexisting P2U and P2Y receptors in the basolateral membrane of K+-secretory epithelial cells in the inner ear and are consistent with the hypothesis that the apical receptors are part of an autocrine negative feedback system in these cells.

Keywords: P2U receptor, P2 agonists, adenosine, DIDS, cibacron blue, suramin, reactive blue 2

Transduction of sound and motion stimuli in the inner ear into nerve impulses depends on homeostatic mechanisms which produce a high concentration of K+ (about 150 mM) in the luminal fluid spaces of the cochlea and of the vestibular labyrinth. It has been shown that the tissues responsible for K+ secretion in the cochlea, utricle and ampullae of the semicircular canals are the strial marginal cells and the vestibular dark cells (Konishi et al., 1978; Kusakari and Thalmann, 1976; Kusakari et al., 1978; Marcus and Shipley, 1994; Wangemann et al., 1995). The transepithelial transport of K+ by these tissues occurs by electrogenic mechanisms, resulting in a transepithelial current directed from the basolateral to the apical side (Sellick and Bock, 1974; Marcus and Shipley, 1994; Marcus and Marcus, 1987; Marcus et al., 1994; Wangemann et al., 1995).

Purinergic receptors have been found not only in excitable cells such as peripheral and central neurons (Illes and Nörenberg, 1993) and smooth muscle cells (Benham and Tsien, 1987) but also epithelial cells (Mason et al., 1991). Purinergic receptors in the inner ear also have recently been given much attention (e.g., (Kujawa et al., 1994a; Aubert et al., 1994; Ashmore and Ohmori, 1990; Dulon et al., 1991)). Purinergic receptors are generally classified as P1, which are activated by adenosine, and P2, which are activated by adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP). Although selective antagonists, if available, would be the pharmacologic method of choice for the classification of receptors, the relative potency of analogues of ATP has been recognized as the current standard for identification of P2 receptors, which have been classified into P2X, P2Y and other subtypes, including a nucleotide receptor (P2U) (Fredholm et al., 1994).

The present study was conducted to determine whether extracellular ATP participates in regulation of vectorial ion transport by the K+-secretory epithelia of the inner ear. The equivalent short circuit current (Isc) has been shown to be a tightly correlated index of K+ secretion under a variety of experimental conditions (Marcus and Shipley, 1994; Marcus and Marcus, 1987; Wangemann et al., 1995). We used the micro-Ussing chamber technique to observe effects on Isc of adenosine, uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP), ATP and several discriminating analogues of ATP applied to either the apical or basolateral sides. The sequence of the magnitude of response of each compound at 10−6 or 10−5 M was assessed from the fractional change of Isc. Under the assumption that each nucleotide used was a full agonist, the sequence derived represents the relative potency of the respective agonist. The results provide evidence for the regulation of transepithelial ion transport by P2U receptors in the apical membrane and by coexisting P2U and P2Y receptors in the basolateral membrane of K+-secretory epithelial cells in the inner ear and are consistent with the hypothesis that the apical receptors are part of an autocrine negative feedback system in these cells.

METHODS

Gerbils 4–10 weeks old (cared for and used under a protocol approved by the Boys Town National Research Hospital Animal Research Committee) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1, intraperitoneally) and decapitated. The temporal bones were removed. The dark cell epithelium on the canal side of the ampulla and stria vascularis with or without spiral ligament from the second or third turn of the cochlea were dissected at 4°C and transferred to the micro-Ussing chamber. Experiments were conducted at 37°C. The micro-Ussing chamber for inner ear tissues has been described previously (Marcus et al., 1994). In brief, the diameter of the aperture between the apical and basolateral side perfusion half-chambers was 80 μm; each side was perfused independently. A change of perfusates was obtained within 1 second. Transepithelial voltage (Vt) was measured with calomel electrodes connected to the chambers via flowing 1M KCl electrodes. Transepithelial current pulses were passed via Ag/AgCl wires. Sample-and-hold circuitry was used to obtain a signal proportional to transepithelial resistance (Rt) from the voltage response to the current pulses; these pulses were removed from the representative records shown here for clarity. The resulting Isc was obtained by calculation (Isc = Vt/Rt).

The calculation of Isc is valid when the epithelium is bathed on both sides with solutions of symmetrical ionic composition since the paracellular pathway is not expected to contribute to Vt in the absence of transepithelial ion concentration differences and since the measurements of Rt were shown to be linear in the range of current used (Marcus et al., 1987).

The control solution contained (in mM): NaCl 150, KH2PO4 0.4, K2HPO4 1.6, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 0.7, glucose 5. Ca2+- and Mg2+-free solution was made by omitting MgCl2 and CaCl2 and adding 0.1 mM ethylene diaminotetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 0.1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether) N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA). All experimental agents were dissolved in the control solution immediately before use. The pH of each solution was adjusted to 7.4 at 37°C. The P2 receptor blocker suramin was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); 2-methylthioadenosine 5′-triphosphate (2-meS-ATP; catalogue no. A023) and α,β-methylene adenosine 5′-triphosphate (α,β-meth-ATP; catalogue no. M-128) were purchased from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA); ATP (catalogue no. A5394), UTP (catalogue no. U4630), adenosine and adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (ATPγS; catalogue no. A1388), cibacron blue 3GA (catalogue no. C9534) and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostibene-2.2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS, catalogue no. D3514) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) and all other reagents were from Sigma or Fluka Chemical (Ronkonkoma, NY). DIDS was predissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) before adding to the control solution (final DMSO concentration 0.1%).

Data are given as mean ± SEM (n = number of tissues). Student’s t-test for paired or unpaired data was used as appropriate. Ratios were first subjected to a logarithmic transformation before application of the t-test to bring the data into a normal distribution (Snedecor and Cochran, 1954). Differences were taken to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Vestibular Dark Cell Epithelium

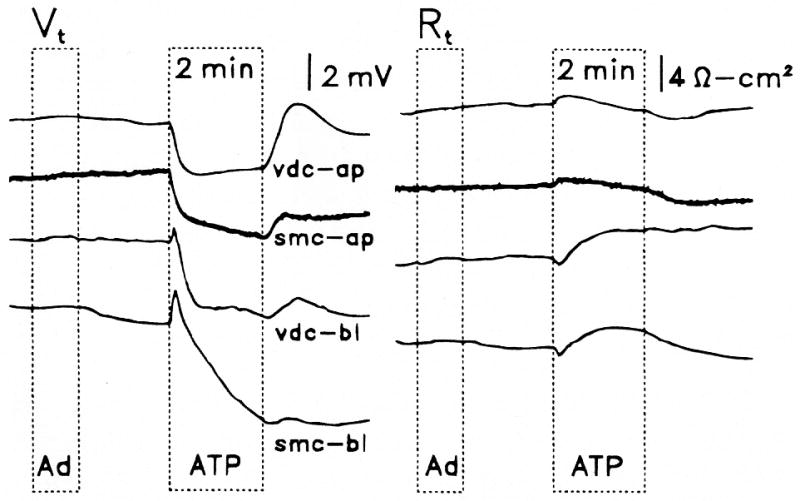

When both apical and basolateral sides were perfused with control solution, Vt and Rt of vestibular dark cells were 11.1 ± 0.2 mV and 17.2 ± 0.4 Ω-cm2, respectively, and Isc was 678 ± 14 μA/cm2 (n=236). Perfusion of adenosine (10−5 M) had no effect on Vt and Rt on either the apical membrane (n=10) or the basolateral membrane (n=7) although ATP produced pronounced effects in paired experiments (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects on transepithelial voltage (Vt) and resistance (Rt) of perfusion of adenosine (Ad, 10−5 M) and adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP, 10−5 M) on the apical membrane of vestibular dark cells (vdc-ap) and strial marginal cells (smc-ap) and on the basolateral membrane of vestibular dark cells (vdc-bl) and strial marginal cells (smc-bl). Representative traces.

Apical side

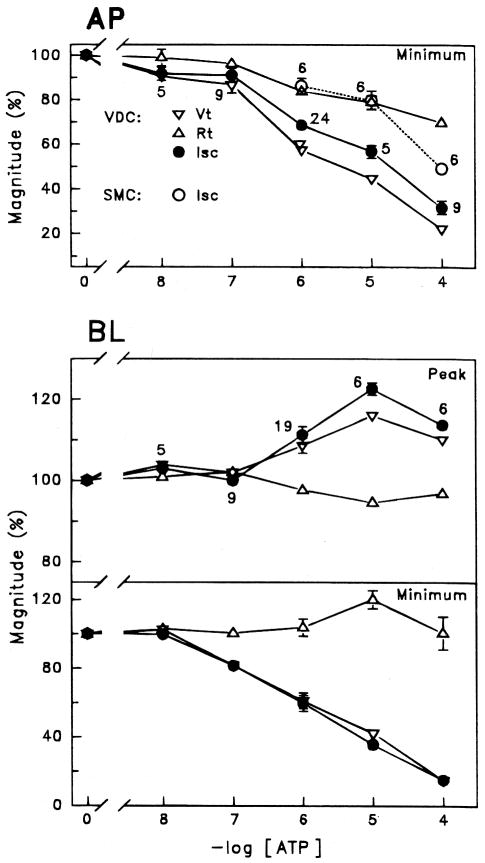

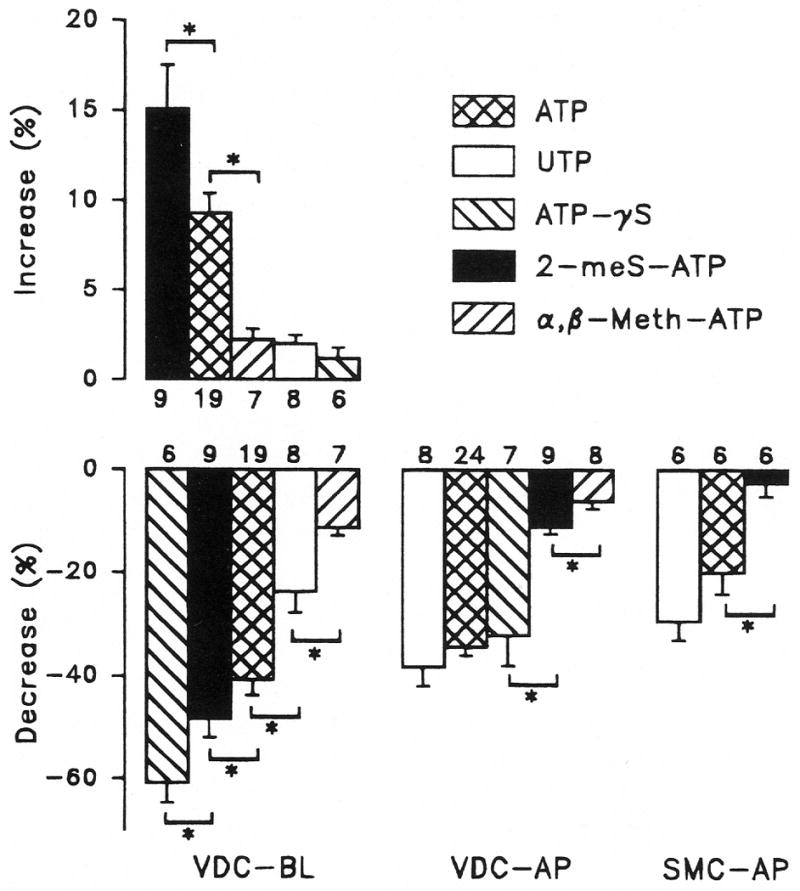

Perfusion of ATP for 2 minutes on the apical side of vestibular dark cells produced a dose-dependent decrease of Vt whereas Rt underwent a transient increase followed by a sustained decrease. On removal of the agonist, there was an overshoot of Vt and Isc of variable size (Figs. 1, 4, 5). A significant decrease in Isc at 2 minutes was found at all concentrations tested between 10−8 and 10−4 M and the response did not fully saturate within this range (Fig. 2). UTP and several analogues of ATP (10−6 M) produced effects on Vt and Rt, which were qualitatively similar to those by ATP (Fig. 3). The sequence of inhibition of Isc was UTP = ATP = ATPγS ≫ 2-meS-ATP > α,β-meth-ATP, corresponding to the sequence defining the P2U receptor (Fredholm et al., 1994).

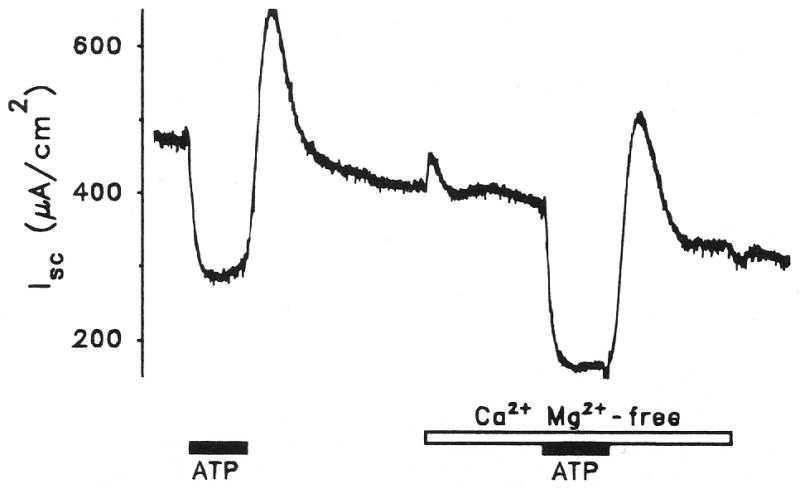

Figure 4.

Effect on transepithelial equivalent short circuit current (Isc) of apical perfusion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (10−6 M) in the presence and absence of Ca2+ and Mg2+. Representative trace from vestibular dark cells.

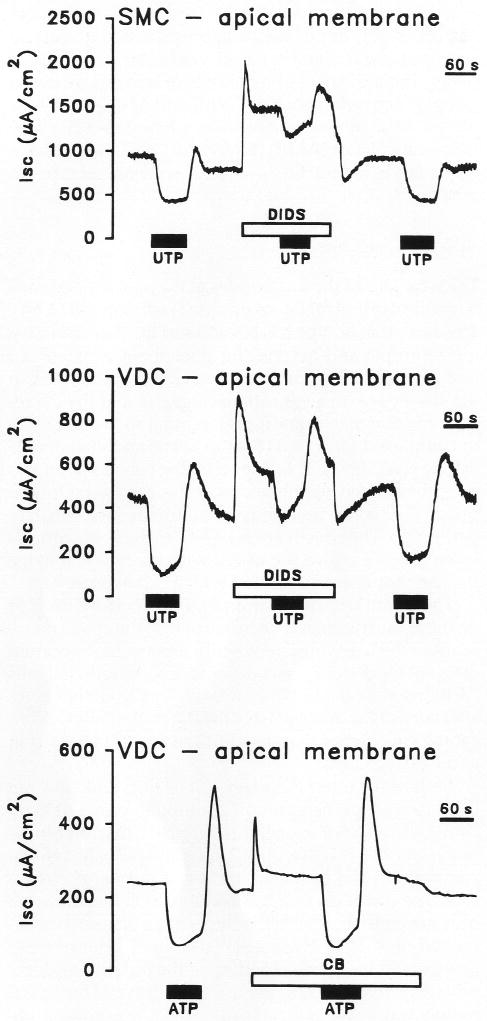

Figure 5.

Representative trace of effect on transepithelial equivalent short circuit current (Isc) of apical perfusion of P2U agonist (uridine 5′-triphosphate) [UTP] or (adenosine 5′-triphosphate) [ATP] in the presence or absence of P2 antagonists (cibacron blue [CB] or 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid [DIDS]. Top: Effects of UTP (10−6 M) and DIDS (10−3 M) on strial marginal cells (SMC); middle: effects of UTP (10−6 M) and DIDS (10−3 M) on vestibular dark cells (VDC); bottom: effects of ATP (10−5 M) and CB (10−5 M) on vestibular dark cells (VDC).

Figure 2.

Summary of effects (minimum and peak) on Vt, Rt and short circuit current (Isc) from 2-minute perfusion of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) expressed as a percent of the respective values immediately prior to ATP; mean ± SEM. Top: Apical (AP) perfusion of vestibular dark cells (VDC) with ATP in the range 10−8 to 10−4 M and of strial marginal cells (SMC) with ATP in the range 10−6 to 10−4 M. Bottom: Basolateral (BL) perfusion of vestibular dark cells with ATP in the range 10−8 to 10−4 M. Number of experiments per concentration is listed next to each data point; numbers were the same for minimum and peak of Vt (basolateral side).

Figure 3.

Apical (AP) and basolateral (BL) perfusion of vestibular dark cells (VDC) with 10−6 M uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP), adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate (ATPγS), 2-methylthioadenosine triphosphate (2-meS-ATP) and α,β-methylene adenosine 5′-triphosphate (α,β-meth-ATP) and apical perfusion of strial marginal cells (SMC) with 10−5 M UTP, ATP and 2-meS-ATP. Top: increase of Isc at peak value during basolateral perfusion of ATP expressed as a percent change from initial value;Bottom: decrease of Isc at 2 minutes of perfusion of ATP expressed as a percent change from initial value. Bars are mean ± SEM; *Significant difference between adjacent bars; number of experiments per concentration is listed next to each bar.

Some P2 receptors have been found to act by opening Ca2+-permeable cation channels, which leads to an increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration and subsequent modification of other ion channel activities (Illes and Nörenberg, 1993; Benham and Tsien, 1987). We tested this possibility in vestibular dark cell apical membrane by perfusing ATP (10−6 M) in the presence and absence of divalent cations in the apical perfusate. Removal of Ca2+ and Mg2+ caused a small transient increase of Isc (10 ± 1%, n=5) and their removal did not prevent the inhibitory effect of ATP on Isc (Fig. 4). The decrease in Isc caused by ATP in the absence of divalent cations (61 ± 4%, n=5) was significantly greater than that when Ca2+ and Mg2+ were present (42 ± 6%, n=4). The effect of ATP in the presence of divalent cations was not significantly different before (42 ± 6%, n=4) and after (35 ± 5%, n=5) exposure to divalent-free solution.

Three antagonists of P2 receptors were tested for their effects on the response of Isc to apical perfusion of P2U agonists. Apical perfusion of suramin (10−6 M), an antagonist of some P2 receptors (Fredholm et al., 1994), had no effect on Isc and did not reduce inhibition of Isc by 10−6 M UTP. The initial Isc values before perfusion of UTP in the absence and presence of suramin were 717 ± 60 (n=8) and 769 ± 49 (n=7) μA/cm2, respectively (P > 0.05). UTP caused decreases (after 2 minutes of perfusion) of 38 ± 4% (n=8) and 32 ± 1% (n=7; P > 0.05).

By contrast, apical perfusion of both DIDS (10−3 M) and cibacron blue (10−5 M) caused a large transient increase in Isc followed by relaxation to a level higher than that under control conditions (Fig. 5). DIDS increased Isc from 439 ± 73 to a peak of 901 ± 78 and a steady-state level of 564 ± 74 μA/cm2 (n=7). Cibacron blue increased Isc from 231 ± 15 to a peak of 397 ± 26 and a steady-state level of 277 ± 16 μA/cm2 (n=5). UTP (10−6 M) decreased Isc by 69 ± 5% (n=7) and 25 ± 4% (n=7) in the absence and presence of DIDS, respectively. The decrease in the presence of DIDS was significantly smaller. ATP (10−5 M) decreased Isc by 68 ± 5% (n=4) and 63 ± 4% (n=5) in the absence and presence of cibacron blue, respectively, and there was no significant difference between the two.

Basolateral Side

Perfusion of ATP on the basolateral side of vestibular dark cells produced dose-dependent changes in Vt and Rt. Vt transiently increased rapidly followed by a pronounced decline. Rt decreased briefly and then slowly increased (Fig. 1). These changes led to a transient increase in Isc followed by a decline (Fig. 2). The effects were poorly reversible during the several minutes of post-exposure observation. A significant decrease in Isc at 2 minutes was found at concentrations above 10−7 M and the response did not completely saturate by 10−4 M. The reduction in the size of the initial increase between 10−5 and 10−4 M ATP is likely due to a larger relative contribution of the process causing the decrease in Isc.

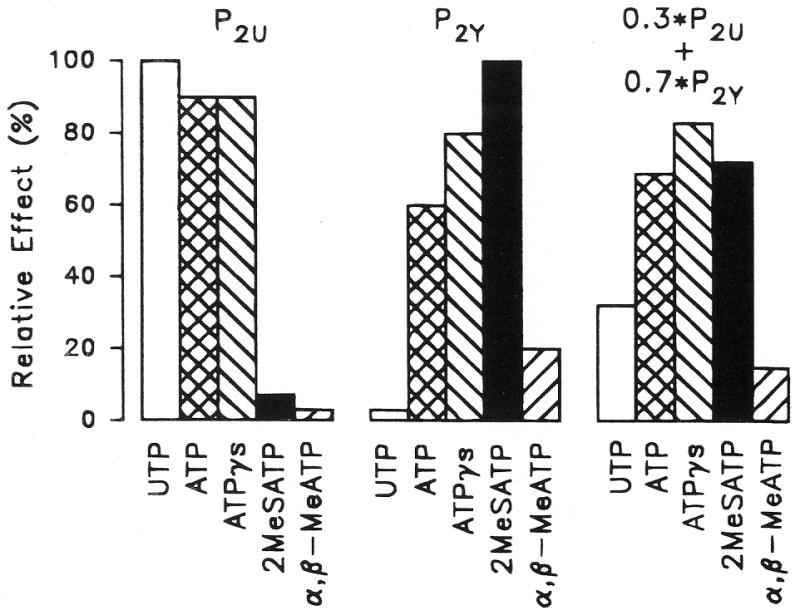

UTP and several analogues of ATP (10−6 M) produced effects on Vt and Rt which were qualitatively similar to those by ATP. The sequence of stimulation of Isc was 2-meS-ATP > ATP ≫ UTP =α,β-meth-ATP = ATPγS, corresponding to the sequence defining the P2Y receptor (Fredholm et al., 1994) (Fig. 3). The sequence of inhibition of Isc at 2 minutes was ATPγS > 2-meS-ATP > ATP > UTP >α,β-meth-ATP, which does not correspond to the sequence defining any one P2 receptor but is consistent with the presence of both P2U and P2Y receptors (see Discussion and, Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Expected responses to P2 agonists of systems containing P2U (left), P2Y (middle) and coexisting P2U (30%) and P2Y (70%) receptor subtypes (right). The response to the most potent agonist for P2U and P2Y was set to 100% and the other agonists were placed in their established sequences of potency. The combined response of the coexisting receptors was derived as a linear combination from the first two sets of responses and corresponds to the sequence found for the basolateral membrane of vestibular dark cells. UTP = uridine 5′-triphosphate; ATP = adenosine 5′-triphosphate. ATPγS = adenosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate; 2-meS-ATP = 2-methylthioadenosine triphosphate; α,β-meth-ATP = α,β-methylene adenosine 5′-triphosphate.

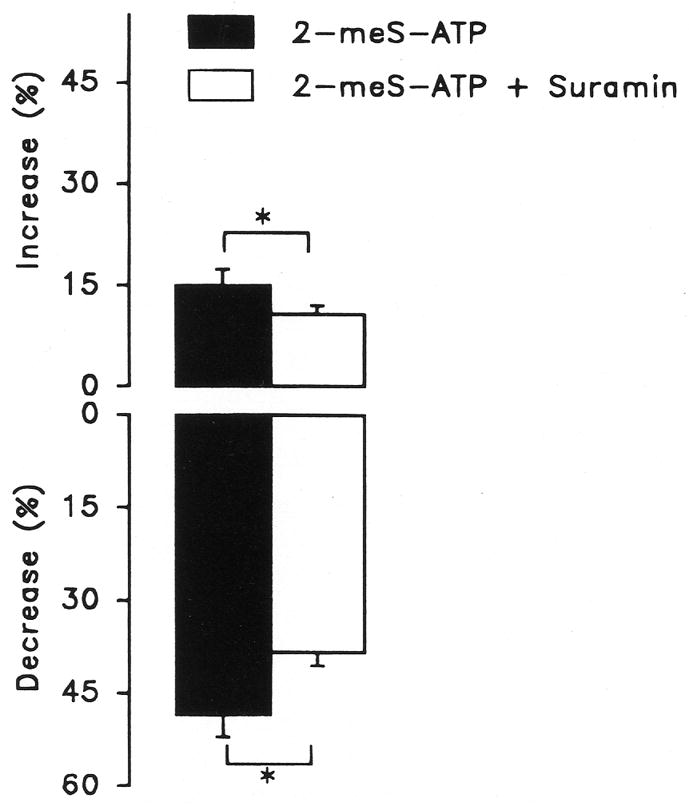

The basolateral side was perfused with 10−6 M 2-meS-ATP, a strong agonist for the P2Y receptor, in the presence and absence of suramin (10−6 M). Suramin had no effect on Isc, whereas both the initial transient stimulation and the later inhibition of Isc by 2-meS-ATP were significantly reduced by suramin (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of basolateral perfusion of 10−6 M 2-methylthioadenosine triphosphate (2-meS-ATP) on short circuit current (Isc) of vestibular dark cells in the presence and absence of 10−6 M suramin. Top: Peak increase in Isc during perfusion of 2-meS-ATP expressed as a percent change from the respective initial values; bottom: decrease of Isc at 2 minutes of perfusion of 2-meS-ATP expressed as percent change from the respective initial values. Bars are mean ± SEM, n=9; *Significant difference between adjacent bars.

Strial Marginal Cell Epithelium

When both apical and basolateral sides of stria vascularis (attached to spiral ligament) were perfused with control solution, Vt and Rt of the stria vascularis were 18.9 ± 0.9 mV and 18.6 ± 1.1 Ω-cm2 corresponding to an Isc of 1067 ± 78 μA/cm2 (n=18). Apical perfusion of adenosine (10−5 M) caused no significant change of either Vt or Rt (n=6) whereas ATP (10−6 to 10−4 M) significantly decreased Isc in the same tissues (Figs. 1, 2, 3). Perfusion of 10−5 M ATP, UTP and 2-meS-ATP on the apical side of strial marginal cells produced responses similar to those of the vestibular dark cells. The sequence of inhibition of Isc at 2 minutes was UTP = ATP ≫ 2-meS-ATP, corresponding to the sequence defining the P2U receptor (Fredholm et al., 1994) (Fig. 3).

Apical perfusion of DIDS and UTP caused similar effects on Isc of stria marginal cells as those observed on vestibular dark cells. DIDS (10−3 M) increased Isc from 985 ± 133 to a peak of 1551 ± 114 and a steady-state level of 1111 ± 166 μA/cm2 (n=6) (Fig. 5). UTP (10−6 M) decreased Isc by 44 ± 6% (n=6) and 27 ± 6% (n=6) in the absence and presence of DIDS, respectively. The decrease in the presence of DIDS was significantly smaller.

Interpretation of results of perfusion of the perilymphatic side of the stria vascularis is complicated by the presence of two continuous cell layers. When the perilymphatic side of stria vascularis (with spiral ligament) was perfused with adenosine (10−5 M) for 1 minute or ATP (10−5 M) for 2 minutes, there was no effect on Isc (n=5). In a subsequent series of experiments (Fig. 1), access of perfusate to the basolateral membrane of the marginal cell epithelial layer was improved by mechanical disruption of the basal cell layer. This was accomplished by removal of the spiral ligament, which is adjacent to the basal cell layer and has been found to increase access of other experimental agents such as bumetanide and ouabain to the basolateral membrane of marginal cells (Wangemann et al., 1995). In this preparation, ATP (10−5 M) initially increased Isc from 507 ± 77 to 603 ± 104 μA/cm2 and subsequently decreased Isc to 172 ± 69 μA/cm2 (n=5), a result qualitatively similar to that in vestibular dark cells. Both the paired increase and decrease were statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

The ion transport pathways which contribute to constitutive secretion of K+ by strial marginal cells and vestibular dark cells have been determined (Marcus and Shipley, 1994; Wangemann et al., 1995; Marcus et al., 1994; Wangemann and Marcus, 1990). Purinergic receptors have been found in a variety of epithelial cells (Mason et al., 1991; Cotton and Reuss, 1991), including sensory and supporting cells of the inner ear (Rennie and Ashmore, 1993; Ashmore and Ohmori, 1990; Kujawa et al., 1994; Aubert et al., 1994; Dulon et al., 1991). It was therefore of interest to determine whether extracellular ATP or its breakdown product, adenosine, might contribute to local regulation of Isc (a manifestation of electrogenic K+ secretion) in dark cells and marginal cells. The present work has shown that adenosine does not acutely affect transcellular electrogenic processes, arguing against the participation of P1 receptors (Ramkumar et al., 1994), but that extracellular ATP at 10−8 to 10−4 M strongly modifies Isc in these tissues. The effects of ATP were likely the result of action on P2 receptors and not of ectonucleotidases since the poorly metabolizable analogue, ATPγS, produced a strong response at both the apical and basolateral membranes of dark cells.

The currently-preferred means of defining purinergic receptors by synthetic analogues has the limitation that the apparent agonist potency depends strongly on the entire signal transduction machinery as well as on agonist binding to the receptor. Despite this limitation, responses of Isc to purinergic agonists at both the apical and basolateral membranes of vestibular dark cells fit closely the sequences of responses of other measures of receptor activation such as formation of inositol phosphates or changes in cytosolic adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) (Boyer et al., 1993), which have been used to define the P2U and P2Y receptor subtypes in other cells.

Apical Membrane

The sequence of the nucleotides at the apical membrane is identical to that for P2U receptors (Fredholm et al., 1994). This receptor subtype has been found in other cells to be metabotropic and act via the phospholipase C (PLC) pathway (see later). The increased effect of apical ATP in the absence of divalent cations suggests that the P2U receptor in that membrane is preferentially activated by an uncomplexed form of ATP, as in aortic endothelial cells (Motte et al., 1993). This suggests that sensitivity of this receptor may be heightened in vivo, since the endolymphatic Ca2+ concentration is substantially lower than in perilymph. The effectiveness of ATP in the absence of divalent cations is also consistent with the notion that the P2U receptor is not associated with a cation channel.

The P2 antagonist suramin had no effect by itself or on the agonist-induced decrease of Isc at the apical membrane, which is consistent with reports that suramin does not block the P2U receptor in aortic endothelial cells (Wilkinson et al., 1993). However, in C6 glioma cells, suramin was an antagonist of the P2U receptor but at concentrations higher than used in the present study (Lin and Chuang, 1994).

Both of the other P2 antagonists, DIDS and cibacron blue, caused an increase in Isc, although only DIDS reduced the effect of exogenous agonist. Cibacron blue is one isomer of reactive blue 2, an ambiguously defined compound used in many studies of purinergic receptors. The increases in Isc caused by DIDS and cibacron blue are consistent with the hypothesis of autocrine secretion of ATP by these cells (see later). Both of these agents may antagonize binding of the putative endogenous ATP released into the unstirred layer of the apical membrane.

The difference between the effects of DIDS and cibacron blue on nucleotide action may be due to differences between antagonist and agonist competitive binding strengths to the receptor so that 10 μM agonist might displace 10 μM cibacron blue, whereas 1 μM agonist might not be able to displace 1 mM DIDS. If this were the case, it would represent a difference between competitive inhibition by these drugs in the P2U receptor of vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells as opposed to the noncompetitive inhibition observed in C6 glioma cells (Lin and Chuang, 1994).

Basolateral Membrane

The responses to nucleotides at the basolateral membrane of vestibular dark cells had a different time course and sequence from that at the apical membrane and these responses suggested the presence of two subtypes of P2 receptor. There was an initial increase in the basolateral response of Isc, which was not present in the apical response. The sequence of the initial increase of Isc is identical to that taken to identify the P2Y subtype (Boyer et al., 1993; Fredholm et al., 1994). The very small effect of UTP on the increase in Isc is also consistent with this interpretation (Fredholm et al., 1994). The data are incompatible with the involvement of a P2X receptor due to differences in the sequence of analogues (Fredholm et al., 1994).

The substantial decreases in Isc by ATP and 2-meS-ATP suggest that P2Y receptors not only participate in the basolateral increase, but also in the basolateral decrease of Isc. Further support for the presence of a P2Y purinergic receptor on the basolateral membrane is the significant effect of suramin on both the stimulatory and inhibitory phase of the action of 2-meS-ATP. Suramin was found to be a competitive antagonist of P2Y receptors in aortic endothelial cells but not an effective antagonist of P2U receptors (Wilkinson et al., 1993). The lack of effect of suramin alone suggests either that the effects observed during perilymphatic perfusion (Kujawa et al., 1994b) were not due to action on marginal cells (assuming the homology between dark cells and marginal cells extends to the effects of suramin) or that the sources of agonist present in vivo are not present in the isolated tissue.

Similar to the effect of UTP on the apical membrane, basolateral UTP produced a substantial decrease of Isc, suggesting the presence also of P2U receptors on the basolateral membrane. The low response to α,β-meth-ATP argues against the participation of the P2X subtype (Fredholm et al., 1994). The sequence found on the basolateral membrane for the nucleotides used in this study can be explained as simply the sum of the responses to coexisting P2U and P2Y receptors. Figure 7 shows an example of how responses having the sequences of the two receptors can add up to yield the observed sequence. Coexisting P2U and P2Y receptors have been found on bovine aortic endothelial cells and C6 glioma cells (Communi et al., 1995; Lin and Chuang, 1994).

Signaling Pathways

Several signaling pathways have been found for P2 receptors in other cells. These include direct ionotropic activation of an associated Ca2+-permeable channel by P2X receptors (Benham and Tsien, 1987; Illes and Nörenberg, 1993) and metabotropic modulation of ion channels by P2U and P2Y receptors (Watson and Girdlestone, 1994; Lin and Chuang, 1994). Metabotropic activation occurs via PLC pathways, which lead to protein phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC) and inositol trisphosphate-dependent Ca2+ release from cytosolic stores (Zheng et al., 1993; Galietta et al., 1994; Ogawa and Schacht, 1993). It has recently been reported that the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration of cultured strial marginal cells increased in response to extracellular ATP (Suzuki et al., 1994) in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+, suggesting the participation of the PLC pathway. Even though the PLC pathway contains many steps, the response can be rapid (5 s), as in aortic endothelial cells (Purkiss et al., 1994). The regulatory pathways utilized by purinergic receptors in vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells remain to be determined, although the apical P2U receptor is probably not ionotropic (see before).

Two possible pathways by which P2 receptors might decrease Isc in dark cells and marginal cells are inhibition of adenylate cyclase, as for P2Y receptors in C6 glioma cells (Boyer et al., 1993; Lin and Chuang, 1994)), and stimulation of PKC, as for P2U and P2Y receptors in aortic endothelial cells (Wilkinson et al., 1993). Preliminary experiments in our laboratory have shown that an increase in cAMP in both vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells causes an increase in Isc and the current through the apical IsK channels (Sunose and Marcus, 1995, unpublished observations). A decrease in cAMP by activation of a P2Y receptor would therefore be expected to cause a decrease in Isc. The presence of adenylate cyclase in the apical membrane and vasopressin receptors in the basolateral membrane of vestibular dark cells of the frog (Ferrary et al., 1991) is consistent with the hypothesis that vasopressin may activate K+ secretion in these cells via elevation of cAMP while extracellular ATP may provide a negative signal to reduce K+ secretion.

Activation of PKC via the PLC pathway could also lead to a decrease in Isc. Preliminary experiments showed that activation of PKC with phorbol ester in the absence of bath Ca2+ caused a decline in the IsK channel current (Sunose and Marcus, unpublished observations). If PKC were activated by stimulation of a P2 receptor, a similar decline of Isc would be expected. Other pathways stimulated by P2Y receptor activation include arachidonic acid production via an increase of cytosolic Ca2+ by release from an intracellular store (Bruner and Murphy, 1990) or directly coupled to phospholipase A2 (Bruner and Murphy, 1993). The transient increase in Isc at the onset of basolateral perfusion of agonist is likely due to a stimulation of the IsK channel, since Rt declines during this time. The mediating signal is unknown.

Hypothesis of Autocrine System

The physiologic function of P2 receptors on epithelial cells as well as the possible source of agonists is presently not known. Currently, an intriguing story is emerging regarding an autocrine feedback mechanism, which involves ATP secretion and regulation of ion transport by purinergic receptors. Evidence has been presented for ATP secretion through cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR)-like apical membrane channels in Cl− secreting epithelia (Xiao et al., 1994; Cantiello et al., 1994). Apical perfusion of exogenous extracellular ATP (or UTP) has been shown in those epithelia to stimulate Cl−-secretion (Stutts et al., 1992; Schwiebert et al., 1994; Urbach et al., 1994) by activation of apical Cl− channels of greater conductance than CFTR, thus amplifying Cl− secretion by CFTR (Stutts et al., 1992; Urbach et al., 1994).

We have found several key elements of this system in vestibular dark cells and strial marginal cells: (1) P2U receptors linked to the regulation of ion transport were found in the apical membrane of both cell types. Submicromolar ATP and UTP each caused a decrease of Isc which was antagonized by DIDS; (2) DIDS in the absence of exogenous P2U agonist caused a substantial increase in Isc, consistent with the hypothesis that agonist is secreted by these cells and that the negative feedback effect of this endogenous agonist can be blocked by DIDS; and (3) anion channels including CFTR-like channels have been reported in stria marginal cell apical membrane (Sunose et al., 1993; Takeuchi et al., 1992). It remains to be shown whether these channels conduct ATP and participate in an autocrine regulatory system.

Purinergic Receptors in the Inner Ear

The influence of extracellular ATP on inner ear function has been studied in both in vitro and in vivo preparations (Ashmore and Ohmori, 1990; Aubert et al., 1994; Kujawa et al., 1994; Mockett et al., 1994; Ogawa and Schacht, 1993; Rennie and Ashmore, 1993; Suzuki et al., 1994) with most emphasis placed on sensory and supporting cells. Isolated sensory structures (Ogawa and Schacht, 1993), inner and outer hair cells (Nakagawa et al., 1990; Ashmore and Ohmori, 1990; Dulon et al., 1991), Deiter’s cells and Hensen’s cells (Dulon et al., 1993) were shown to contain P2 receptors, which cause an increase in PLC activity and cytosolic Ca2+ (Ashmore and Ohmori, 1990; Rennie and Ashmore, 1993; Ogawa and Schacht, 1993). Extracellular ATP was recently shown to increase cytosolic Ca2+ in cultured cells from stria vascularis (Suzuki et al., 1994). In addition to evidence for P2 receptors, Mockett et al. (1994) recently reported evidence for ectonucleotidase activity on outer hair cells, which would provide a means to degrade ATP after action on the receptors.

Perilymphatic perfusion of ATP and 2-meS-ATP in the frog semicircular canal in vitro had little effect on the transepithelial potential (Aubert et al., 1994), which is not consistent with the present findings in the isolated dark cell epithelium from the gerbil. The origin of this difference is not clear, although species differences may play a role. ATP and analogues perfused through the cochlear perilymphatic space of guinea pig led to effects on compound action potential, summating potential, distortion product otoacoustic emissions and endocochlear potential (Kujawa et al., 1994a). Consistent with our findings, no evidence was found for the presence of adenosine (P1) receptors. Effects of the nucleotides were interpreted as being mediated by P2 receptors, although the concentrations necessary to elicit the effects were unusually high. The necessity for high concentrations may have been due in part to dilution of the perfusate with cerebralspinal fluid (Hara et al., 1989). The transient increase in the endocochlear potential observed in those experiments was conceivably due to diffusion of agonist past the basal cell barrier and acting on the strial marginal cells as seen shortly after the onset of basolateral perfusion in the present experiments (Fig. 1). This increase was likely not seen in our experiments on isolated stria vascularis with intact basal cell layer (with spiral ligament) since the concentration of agonist was a decade less than in the other study.

The present findings are consistent with the presence of two purinergic receptor subtypes present in K+-secretory cells of the inner ear, P2U receptors in the apical membrane and coexisting P2Y and P2U receptors in the basolateral membrane, which may contribute significantly to the regulation of transepithelial ion transport processes in these tissues. It remains to be determined whether these purinergic receptors participate in an autocrine negative feedback loop for self-control of the rates of ion transport via regulated secretion of purinergic receptor agonists, which transport pathways are regulated by these receptors and by what intracellular regulatory pathways these receptors modulate the ion transport mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Philine Wangemann for her helpful discussion. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 DC00212 and R29 DC01098.

References

- Ashmore JF, Ohmori H. Control of intracellular calcium by ATP in isolated outer hair cells of the guinea-pig cochlea. J Physiol (Lond) 1990;428:109–131. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert A, Norris CH, Guth PS. Influence of ATP and ATP agonists on the physiology of the isolated semicircular canal of the frog (Rana pipiens) Neuroscience. 1994;62:963–974. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Tsien RW. A novel receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable channel activated by ATP in smooth muscle. Nature. 1987;328:275–278. doi: 10.1038/328275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JL, Lazarowski ER, Chen XH, Harden TK. Identification of a P2Y-purinergic receptor that inhibits adenylyl cyclase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:1140–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner G, Murphy S. ATP-evoked arachidonic acid mobilization in astrocytes is via a P2Y-purinergic receptor. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1569–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner G, Murphy S. Purinergic P2Y receptors on astrocytes are directly coupled to phospholipase A2. Glia. 1993;7:219–224. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantiello HF, Jackson GR, Prat AG, Gazley JL, Forrest JN, Jr, Ausiello DA. Characteristics of the ATP-conductive pathway in shark rectal gland cells. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:39a . doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C466. (abstract) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Communi D, Raspe E, Pirotton S, Boeynaems JM. Coexpression of P2Y and P2U receptors on aortic endothelial cells. Comparison of cell localization and signaling pathways. Circ Res. 1995;76:191–198. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton CU, Reuss L. Electrophysiological effects of extracellular ATP on Necturus gallbladder epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:949–971. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.5.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulon D, Moataz R, Mollard P. Characterization of Ca2+ signals generated by extracellular nucleotides in supporting cells of the organ of Corti. Cell Calcium. 1993;14:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(93)90071-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulon D, Mollard P, Aran JM. Extracellular ATP elevates cytosolic Ca2+ in cochlear inner hair cells. Neuroreport. 1991;2:69–72. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrary E, Oudar O, Bernard C, Friedlander G, Feldmann G, Sterkers O. Adenylate cyclase in the semicircular canal. Hormonal stimulation and ultrastructural localization. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1991;111:281–285. doi: 10.3109/00016489109137388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Daly JW, Harden TK, Jacobson KA, Leff P, Williams M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta LJV, Zegarra-Moran O, Mastrocola T, Wöhrle C, Rugolo M, Romeo G. Activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ and Cl− currents by UTP and ATP in CFPAC-1 cells. Pflügers Arch. 1994;426:534–541. doi: 10.1007/BF00378531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara A, Salt AN, Thalmann R. Perilymph composition in scala tympani of the cochlea: influence of cerebrospinal fluid. Hear Res. 1989;42:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illes P, Nörenberg W. Neuronal ATP receptors and their mechanism of action. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90030-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T, Hamrick PE, Walsh PJ. Ion transport in guinea pig cochlea. I. Potassium and sodium transport. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1978;86:22–34. doi: 10.3109/00016487809124717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Erostegui C, Fallon M, Crist J, Bobbin RP. Effects of adenosine 5′-triphosphate and related agonists on cochlear function. Hear Res. 1994a;76:87–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Fallon M, Bobbin RP. ATP antagonists cibacron blue, basilen blue and suramin alter sound-evoked responses of the cochlea and auditory nerve. Hear Res. 1994b;78:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakari J, Ise I, Comegys TH, Thalmann I, Thalmann R. Effect of ethacrynic acid, furosemide, and ouabain upon the endolymphatic potential and upon high energy phosphates of the stria vascularis. Laryngoscope. 1978;88:12–37. doi: 10.1002/lary.1978.88.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakari J, Thalmann R. Effects of anoxia and ethacrynic acid upon ampullar endolymphatic potential and upon high energy phosphates in ampullar wall. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:132–147. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197601000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WW, Chuang DM. Different signal transduction pathways are coupled to the nucleotide receptor and the P2Y receptor in C6 glioma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:926–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Liu J, Wangemann P. Transepithelial voltage and resistance of vestibular dark cell epithelium from the gerbil ampulla. Hear Res. 1994;73:101–108. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Marcus NY, Greger R. Sidedness of action of loop diuretics and ouabain on nonsensory cells of utricle: a micro-Ussing chamber for inner ear tissues. Hear Res. 1987;30:55–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Shipley AM. Potassium secretion by vestibular dark cell epithelium demonstrated by vibrating probe. Biophys J. 1994;66:1939–1942. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80987-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus NY, Marcus DC. Potassium secretion by nonsensory region of gerbil utricle in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:F613–F621. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.253.4.F613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SJ, Paradiso AM, Boucher RC. Regulation of transepithelial ion transport and intracellular calcium by extracellular ATP in human normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1649–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockett BG, Housley GD, Thorne PR. Fluorescence imaging of extracellular purinergic receptor sites and putative ecto-ATPase sites on isolated cochlear hair cells. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6992–7007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06992.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motte S, Pirotton S, Boeynaems JM. Evidence that a form of ATP uncomplexed with divalent cations is the ligand of P2y and nucleotide/P2u receptors on aortic endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109:967–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Akaike N, Kimitsuki T, Komune S, Arima T. ATP-induced current in isolated outer hair cells of guinea pig cochlea. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:1068–1074. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.5.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Schacht J. Receptor-mediated release of inositol phosphates in the cochlear and vestibular sensory epithelia of the rat. Hear Res. 1993;69:207–214. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90109-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkiss JR, Wilkinson GF, Boarder MR. Differential regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate by co-existing P2Y-purinoceptors and nucleotide receptors on bovine aortic endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;111:723–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar V, Ravi R, Wilson MC, Gettys TW, Whitworth C, Rybak LP. Identification of A1 adenosine receptors in rat cochlea coupled to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C731–C737. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.3.C731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie KJ, Ashmore JF. Effects of extracellular ATP on hair cells isolated from the guinea-pig semicircular canals. Neurosci Lett. 1993;160:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90409-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Egan ME, Guggino WB. CFTR- and cyclic AMP-stimulated ATP release from airway epithelial cells is required for stimulation of outwardly rectifying chloride channels. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:39a–40a. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Sellick PM, Bock GR. Evidence for an electrogenic potassium pump as the origin of the positive component of the endocochlear potential. Pflügers Arch. 1974;352:351–361. doi: 10.1007/BF00585687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. Iowa State Press; Ames: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Stutts MJ, Chinet TC, Mason SJ, Fullton JM, Clarke LL, Boucher RC. Regulation of Cl- channels in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells by extracellular ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1621–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunose H, Ikeda K, Saito Y, Nishiyama A, Takasaka T. Nonselective cation and Cl channels in luminal membrane of the marginal cell. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1993;265:C72–C78. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunose H, Marcus DC. Elevated intracellular cAMP activates apical Isk channels in vestibular dark cells of Mongolian gerbil. Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 1995;18:26. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Ikeda K, Sunose H, Hozawa K, Kusakari C, Katori Y, Takasaka T. Extracellular ATP increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration in the cultured marginal cells. Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 1994;17:135. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00055-9. (abstract) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S, Marcus DC, Wangemann P. Ca2+-activated nonselective cation, maxi K+ and Cl− channels in apical membrane of marginal cells of stria vascularis. Hear Res. 1992;61:86–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90039-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach V, Prosser E, Raffin J, Thomas S, Harvey BJ. Activation of Cl-channel by extracellular UTP in human lung epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:42a. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, Liu J, Marcus DC. Ion transport mechanisms responsible for K+ secretion and the transepithelial voltage across marginal cells of stria vascularis in vitro. Hear Res. 1995;84:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00009-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P, Marcus DC. K+-induced swelling of vestibular dark cells is dependent on Na+ and Cl− and inhibited by piretanide. Pflügers Arch. 1990;416:262–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00392062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson S, Girdlestone D. 1994 receptor and ion channel nomenclature. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;5(Suppl):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GF, Purkiss JR, Boarder MR. The regulation of aortic endothelial cells by purines and pyrimidines involves co-existing P2y-purinoceptors and nucleotide receptors linked to phospholipase C. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108:689–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12862.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, O’Riordan CR, Cantiello HF. Characteristics of the cardiac CFTR-mediated ATP currents in rat neonatal cardiac myocytes in culture. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:38a. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Christie A, Levy MN, Scarpa A. Modulation by extracellular ATP of two distinct currents in rat myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1993;264:C1411–C1417. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]