Abstract

The aim of this study is to investigate the association between childhood obesity and asthma, and whether this relationship varies by race/ethnicity. For this population-based, cross-sectional study, measured weight and height, and asthma diagnoses were extracted from electronic medical records of 681,122 patients aged 6–19 years who were enrolled in an integrated health plan 2007–2009. Weight class was assigned based on BMI-for-age. Overall, 18.4% of youth had a history of asthma and 10.9% had current asthma. Adjusted odds of current asthma for overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese youth relative to those of normal weight were 1.22 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.20, 1.24), 1.37 (95% CI: 1.34, 1.40), and 1.68 (95% CI: 1.64, 1.73), respectively (P trend < 0.001). Black youth are nearly twice as likely (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 1.93, 95% CI: 1.89, 1.99), and Hispanic youth are 25% less likely (adjusted OR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.77), to have current asthma than to non-Hispanic white youth. However, the relationship between BMI and asthma was strongest in Hispanic and weakest in black youth. Among youth with asthma, increasing body mass was associated with more frequent ambulatory and emergency department visits, as well as increased inhaled and oral corticosteroid use. In conclusion, overweight, moderate, and extreme obesity are associated with higher odds of asthma in children and adolescents, although the association varies widely with race/ethnicity. Increasing BMI among youth with asthma is associated with higher consumption of corticosteroids and emergency department visits.

Introduction

Asthma and obesity are common chronic disorders for which the prevalence among youth in the United States has dramatically increased over the last two decades (1,2). Several cross-sectional and prospective studies have examined the association between obesity and asthma in children and adolescents (3,4,5,6,7) and reported an increased risk for asthma associated with obesity (4,5,6,7). Although the precise mechanism underlying the relationship between asthma and increasing body weight is not well understood, investigators have suggested a link between the pro-inflammatory state in obesity and the increasing prevalence of asthma (7,8,9,10).

However, studies examining asthma risk associated with overweight in children and adolescents have yielded inconsistent findings (3,5,6,11,12), and scant information exists on the relationship between extreme obesity and asthma in this population. In addition, while many investigators have reported increased odds of asthma for black compared to non-Hispanic white youth (1,4,7,13), findings were inconsistent for Hispanics (1,4,13); Asian/Pacific Islanders and other racial/ethnic minority groups were rarely examined. The contribution of increasing body weight to asthma risk, in the context of racial/ethnic-specific effects, has not been thoroughly investigated.

In addition to an increased risk for asthma, obesity may be associated with asthma severity and/or poor asthma control. Studies in adult asthma patients have shown that those who are obese are more symptomatic, require a greater number of asthma medications, and have more frequent emergency department visits than their nonobese counterparts (14,15,16,17). However, such reports in overweight or obese youth with asthma are controversial (7,12,18,19).

In this study, we describe the prevalence of asthma in a large, multiethnic population-based cohort of children and adolescents in Southern California, and examine its association with anthropometric, demographic, and clinical characteristics of the youth in the study. In order to assess whether the effect of increasing body weight on asthma varies for youth of different race/ethnicities, we also examined this association stratified by race/ethnicity. Finally, we investigated the degree to which increasing body weight was associated with asthma-specific medications and health-care utilization among youth with asthma.

Methods and Procedures

Population and data sources

The Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) Children's Health Study is a large, population-based cohort study (n = 920,034) comprised of youth, aged 2–19 years, who were members of a prepaid, integrated health plan between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2009, who received their care in medical offices and hospitals owned by KPSC (20). For the present cross-sectional study, we examined a subset of patients enrolled in the KPSC Children's Health Study. Briefly, we excluded patients who were pregnant (n = 6,898) or younger than 6 years of age (n = 232,014), leaving 681,122 patients to be included in the present study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of KPSC.

Anthropometrics

Height and body weight measurements were extracted from electronic health records and were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2). The median BMI-for-age of all encounters in the year of study enrollment (2007, 2008 or 2009) was selected as the measure to be used for analysis. Based on a validation study including 15,000 patients with 45,980 medical encounters, the estimated error rate in body weight and height data was <0.4% (21). Age- and sex-adjusted BMI z-scores were derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) national standards (22,23). In conjunction with the World Health Organization's (WHO) definitions for overweight and obesity in adults (24), BMI z-scores were used to classify youth into the following BMI categories: “underweight” (<5th percentile), “normal weight” (≥5th and <85th percentiles), “overweight” (≥85th and <95th percentiles, or BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), “moderately obese” (> 95th percentile, or BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), and “extremely obese” (≥1.2 × 95th percentile, or BMI ≥35 kg/m2).

Asthma status

History of asthma was defined as presence of physician diagnosis of asthma, identified by ICD-9 code 493, and at least one prescription for an asthma-specific medication in the medical record prior to study enrollment. Among these youth, those who had a diagnosis of asthma and at least one asthma-specific medication listed in the medical record within the year prior to study enrollment were considered to have current asthma. All other patients, including those who had either a diagnosis of asthma in the medical record or prescriptions for asthma medications but not both, were classified as not having asthma.

Asthma medication

Asthma prescriptions listed in the medical record were identified for youth with current asthma, for 1 year prior to through year of study enrollment. Prescriptions for asthma treatment were categorized as rescue medications (Albuterol, Metaproterenol, Ipratropium, Ipratropium-Albuterol, Levalbuterol, Pirbuterol), inhaled corticosteroids (Fluticasone, Fluticasone-Salmeterol, Flunisolide, Mometasone, Triamcinolone, Beclomethasone, Budesonide, Budesonide-Formoterol), oral steroids (Hydrocortisone, Dexamethasone, Predinosone, Prednisolone, Fludrocortisone, Methylprednisolone), leukotriene modifiers (Zafirlukast, Montelukast, Zileuton), other inhaled medications (Formoterol, Cromolyn, Salmeterol, Nedocromil), and other oral medications (Aminophylline, Theophylline, Terbutaline). For analytic purposes, asthma medications were grouped hierarchically into the following categories: (i) oral corticosteroids, alone or in combination with any other medication, (ii) inhaled corticosteroids, alone or in combination with any other medication except oral corticosteroids, and (iii) rescue medications, alone or in combination with any other medication except inhaled corticosteroids or oral corticosteroids.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Age, sex, and race/ethnicity information were obtained from health plan administrative records and birth certificates and for unknown race/ethnicity information (31.7%) by an imputation algorithm based on surname lists and address information derived from the U.S. Census Bureau (25,26,27). The resulting specificity and positive predictive values were >98% for all major races/ethnicities (20).

Neighborhood education and household income were derived from the linkage of health plan member addresses with US census block data via geocoding (20). Participation in Medi-Cal or other California state-subsidized program for low-income children and families, as well as elderly, blind, or disabled individuals, was assessed from administrative records. Number of asthma-specific health-care encounters, classified as ambulatory or emergency department visits for which an asthma code (ICD-9: 493) was entered in the electronic health record at the time of the visit, were identified for the 1-year period corresponding to study enrollment.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized with proportions and reported by asthma status. Chi-square tests were used to assess differences in proportions of demographic and clinical characteristics among youth with and without current asthma. The association between current asthma and categories of BMI (underweight/normal weight, overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese) was assessed with multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and Medi-Cal insurance status. In order to assess whether, and to what extent the relationship between weight class and asthma is modified by race/ethnicity, we tested for interaction between race/ethnicity and weight class in models adjusted for age, sex, and Medi-Cal insurance status. Based on these models, we report adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for asthma stratified by race/ethnicity. Additionally, we examined prescriptions for asthma medications and health-care utilization among youth with current asthma. Differences in the proportion of youth treated with certain asthma medications across BMI categories were assessed with chi-square tests, and adjusted differences were determined by multivariable logistic regression. Adjusted differences in rate of asthma-specific health-care utilization for different BMI categories were assessed with Poisson regression models using robust standard errors. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

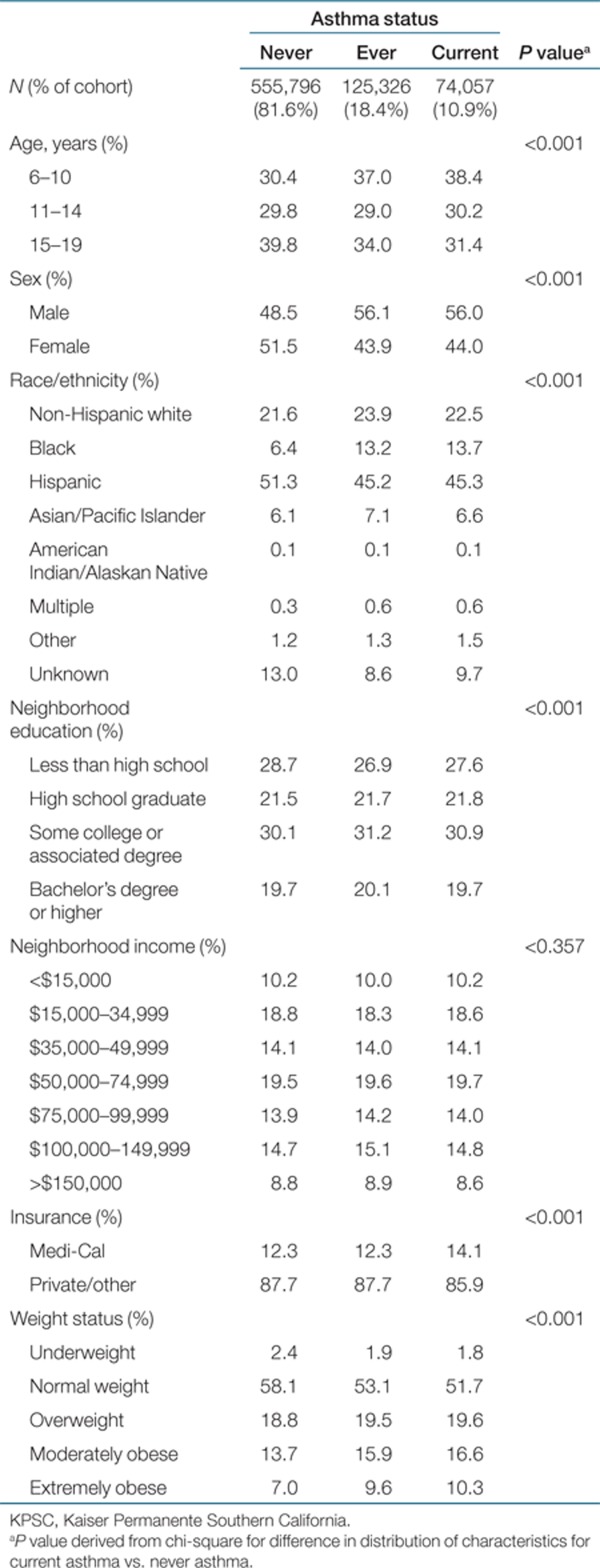

Of the 681,122 youth included in the study, 125,326 (18.4% of the cohort) had a history of asthma while a member of Kaiser Permanente. Current asthma was prevalent among 74,057 youth (10.9% of the cohort) (Table 1). Youth with current asthma were generally similar to those with a history of asthma. However, youth with current asthma were more likely to be younger, male, or black compared to those who had never had asthma. Although differences in the probability of neighborhood education and income levels were statistically significant, youth with current asthma were relatively similar in the distribution of these demographic characteristics to youth who had never had asthma. Youth with current asthma included a slightly higher proportion of those utilizing Medi-Cal insurance and were more likely to be overweight, moderately obese, or extremely obese than those without asthma.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of 681,122 KPSC youth by asthma status.

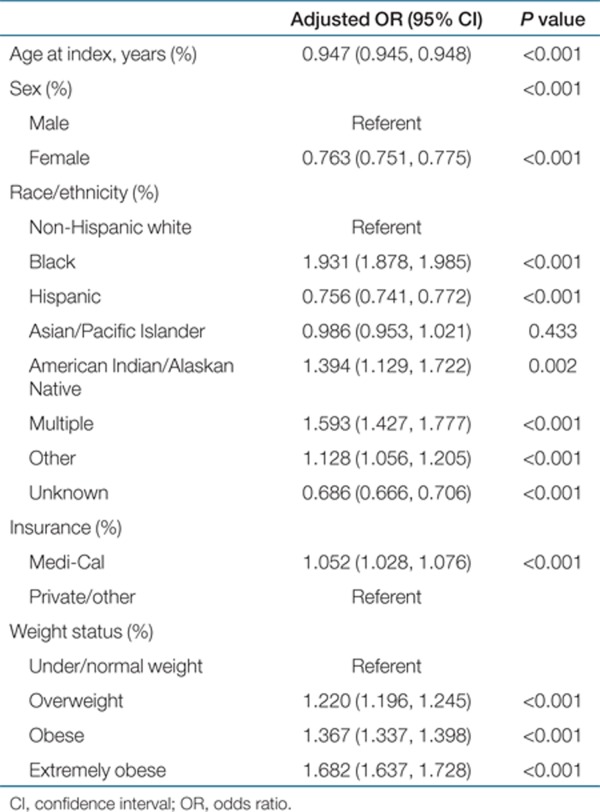

In a multivariable model that included the demographic and anthropometric characteristics shown in Table 2, odds of current asthma were highest for black children and adolescents; black youth were 1.93 times as likely (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.88, 1.99) to have current asthma compared to non-Hispanic white youth. American Indian/Alaskan Native youth were also more likely to have current asthma than non-Hispanic whites (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.72), while Hispanic youth were less likely (OR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.77). After accounting for race/ethnicity and all other demographic characteristics, increasing BMI category was associated with significantly increased odds of current asthma (Table 2). Odds of current asthma for overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese youth relative to under/normal weight youth were 1.22 (95% CI: 1.20, 1.24), 1.37 (95% CI: 1.34, 1.40), and 1.68 (95% CI: 1.64, 1.73), respectively (P for trend < 0.001). Odds of current asthma were not altered by additional adjustment for other covariates listed in Table 1.

Table 2. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of having current asthma (74,057 cases) for selected sociodemographic factors.

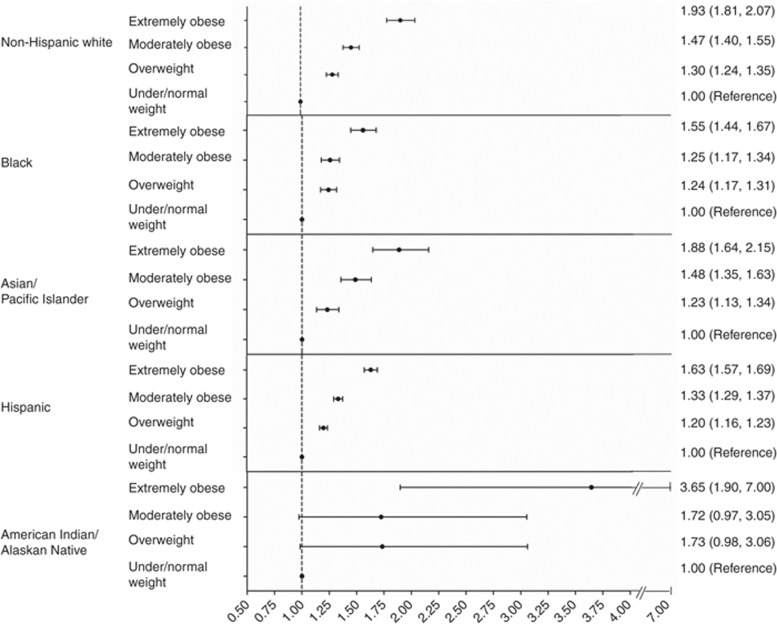

The effect of increasing BMI category significantly varied by race/ethnicity (interaction P < 0.001), with or without adjustment for demographic confounders (Figure 1). Among non-Hispanic white youth, those who were overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese were 1.30 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.35), 1.47 (95% CI: 1.40, 1.55), and 1.93 times as likely (95% CI: 1.81, 2.07), respectively, to have current asthma as those who were normal weight, after adjustment for age, sex, and Medi-Cal status. While black youth were generally more likely to have current asthma than non-Hispanic white youth, the effect of increasing weight class within blacks did not vary as widely. Among Asian/Pacific Islanders, the trend in odds of current asthma for increasing body weight was relatively similar to that observed for non-Hispanic white youth. Extremely obese youth of American Indian/Native Alaskan ethnicity were 3.65 times as likely (95% CI: 1.90, 7.00) to have current asthma as their normal weight counterparts; odds of current asthma for overweight and moderately obese American Indian/Native Alaskan youth were higher than those estimated for any other racial/ethnic group, although they lacked statistical significance because of a reduced sample size. Although Hispanic race/ethnicity generally appeared to be protective for current asthma when compared to non-Hispanic whites, overweight, moderate, and extreme obesity were all significantly associated with an increased risk for current asthma compared to normal weight among Hispanic youth.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) for current asthma vs. BMI category, by race/ethnicity. All models adjusted for age, sex, and Medi-Cal status. CI, confidence interval.

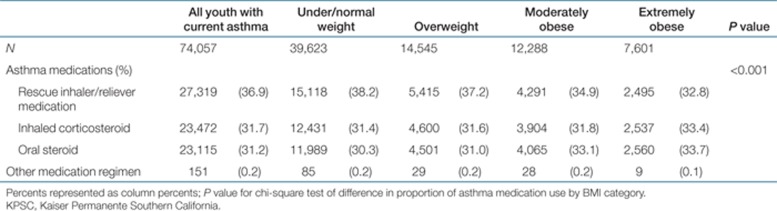

Overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese youth with current asthma were more likely to have been treated with medication regimens that included inhaled and oral corticosteroids than normal weight youth with asthma (Table 3). After adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and Medi-Cal status, extremely obese youth were 18% more likely (P < 0.001) to have been treated with oral corticosteroids, alone or in combination with other medications, than those of normal weight. Extremely obese youth were also 9% more likely (P = 0.001) than their normal weight counterparts to have been treated with inhaled corticosteroids, alone or in combination with any medication except oral steroids.

Table 3. Asthma medication use among KPSC youth with current asthma (age >6) in year prior to index date.

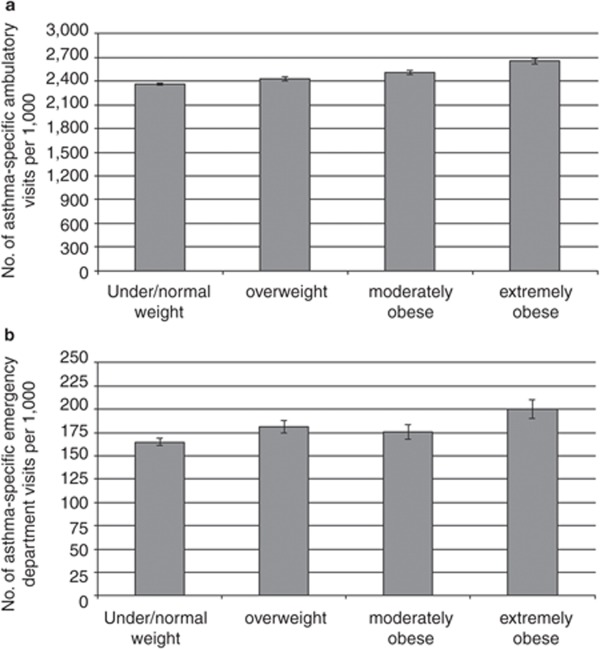

In addition to more frequent treatment with inhaled or oral corticosteroids, extremely obese youth with asthma also had greater asthma-specific health-care utilization than normal weight youth with asthma (Figure 2). During the year of study enrollment, extremely obese youth with asthma had a significantly higher rate of asthma-related ambulatory care visits (2,649 visits per 1,000 youth vs. 2,359 visits per 1,000 youth; P < 0.001), as well as asthma-specific visits to the emergency department (200 visits per 1,000 youth vs. 165 visits per 1,000 youth; P < 0.001) than youth with asthma of normal weight. After adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and Medi-Cal status, extremely obese children and adolescents were expected to have an average of 274 more asthma-related ambulatory visits per 1,000 youth (P < 0.001) and 23 more asthma-specific emergency department visits per 1,000 youth (P < 0.001) than their normal weight counterparts, in a 1-year period.

Figure 2.

Panel (a) represents the rate of asthma-specific ambulatory visits and panel (b) represents the rate of asthma-specific emergency department visits, per 1,000 youth (95% CI), by BMI category. CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In this large, population-based cross-sectional study, overweight, moderate obesity, and extreme obesity were associated with an increased frequency of asthma. Moderately and extremely obese youth had a 37% and 68% higher frequency of asthma, respectively. Several cross-sectional studies (4,6,7) and prospective studies (5,8) have reported associations between obesity, typically defined as > 95th percentile of BMI-for-age, and asthma in children. However, studies that examined the contribution of overweight to asthma risk yielded inconsistent findings, with some reporting a positive association (5,7), and others reporting no association (8); none specifically examined the role of extreme obesity.

In the 1996–2006, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) population aged 2–19 years, Visness et al. reported a prevalence of current asthma ranging from 9.0% to 10.7% per study year; the prevalence of current asthma for 2005–2006 was 10.7% (s.e. 0.5%), which is comparable to the estimated prevalence in our study (7). These investigators also reported an adjusted OR for asthma risk of 1.32 (95% CI: 1.08–1.60) among overweight, and 1.68 (95% CI: 1.33–2.12) among obese youth (7). These estimates are slightly higher than those described in this study, but may be due to the fact that NHANES assessed asthma status by self-report, included children from 2 years of age, and did not distinguish between moderate and extreme obesity (7).

Results from our study also suggest that the magnitude of association between the degree of obesity and asthma substantially varies by race. Few studies have examined the association between increasing BMI and asthma within racial/ethnic groups, and results are inconsistent. Brenner et al. found no association between obesity and asthma in 774 black adolescents (3). However, the null finding in this study may be due to a small sample size, especially in the extreme ranges of BMI. Luder et al. reported a significant association between increasing BMI and moderate to severe asthma among 1,017 black and Hispanic youth aged 6–13 (12). Specifically, these investigators found that youth with asthma were 1.34 times as likely to be overweight, and 1.51 times as likely to be obese (12); these estimates of association are relatively similar to those we report in our study. Despite our modest American Indian/Native Alaskan sample size (n = 610), which limited our power to detect associations in some BMI groups, our findings of increased asthma prevalence among obese American Indian/Alaskan Native youth are highly consistent with a recent study conducted in 1,852 children from Northern Plains American Indian communities (28). In this report, Noonan et al. observed that overweight and obese youth were 1.72 times as likely to have current asthma compared to those of normal weight (28), an estimate nearly identical to those we reported in our study for overweight and obese youth, respectively.

While some studies reported associations between increasing BMI and emergency department admission rates among youth with asthma (7), others did not (29). Our findings support the notion that extremely obese children and adolescents with asthma have greater health-care utilization, including both ambulatory and emergency room visits, than their normal weight counterparts. Other studies have reported higher number of asthma medications prescribed to overweight and obese youth with asthma compared to those of normal weight (12). Our results also suggest that overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese youth are more likely to be prescribed inhaled and oral steroids. Considered together, these findings may imply that obese youth are more symptomatic and/or have more severe asthma than normal weight youth with asthma.

We acknowledge that our cross-sectional design precluded us from assessing changes in asthma severity, which may be associated with obesity, or changes in body weight, which may be associated with asthma. Another limitation of our study is the lack of detailed information on specific asthma-related characteristics, such as wheezing and asthma attacks. Electronic health records did not include details on ethnic heritage, which would have allowed for further stratification among specific Hispanic subgroups known to have different asthma risks, or direct measures of lung function, such as forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume, and forced expiratory flow rate which would also have allowed us to more accurately assess asthma status and severity. In addition, we were unable to control for certain environmental exposures or behaviors known to exacerbate asthma symptoms such as household smoking, pet dander, and air pollution, as well as physical activity or participation in sports.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. Our population-based approach, combined with our large, multiethnic and diverse pediatric population, allowed us to examine a wide range of BMI within racial/ethnic groups that have not been previously investigated. While our American Indian/Native Alaskan sample was relatively small in size (n = 610), which limited our ability to detect modest associations between overweight and asthma, we were well powered to detect associations between extreme obesity and asthma, which were of larger magnitude. The high prevalence of extreme obesity, especially among racial/ethnic minorities, allowed for stable estimates of associations with high body weight in most minority groups. Additional strengths of the study include the availability of asthma diagnoses made by physicians rather than reliance on self-report, and the availability of asthma-specific prescription and health-care utilization information.

In conclusion, the findings of our study suggest that the association between increasing body mass and childhood asthma varies by race/ethnicity. Obesity, especially extreme obesity, may influence the prevalence of asthma in Asian/Pacific Islander and non-Hispanic white youth to a larger extent than in black or Hispanic youth. An increasing degree of obesity appears to further exacerbate asthma-related health-care utilization and treatment. Effective interventions are needed to target high risk populations in order to avoid medical emergencies among children with asthma.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders (NIDDK, R21DK085395, Principal Investigator: CK) and Kaiser Permanente Direct Community Benefit Funds.

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ. Status of childhood asthma in the United States, 1980–2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123 Suppl 3:S131–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner JS, Kelly CS, Wenger AD, Brich SM, Morrow AL. Asthma and obesity in adolescents: is there an association. J Asthma. 2001;38:509–515. doi: 10.1081/jas-100105872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez MA, Winkleby MA, Ahn D, Sundquist J, Kraemer HC. Identification of population subgroups of children and adolescents with high asthma prevalence: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:269–275. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Islam T.et al. Obesity and the risk of newly diagnosed asthma in school-age children Am J Epidemiol 2003158406–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad N, Biswas S, Bae S.et al. Association between obesity and asthma in US children and adolescents J Asthma 200946642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visness CM, London SJ, Daniels JL.et al. Association of childhood obesity with atopic and nonatopic asthma: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2006 J Asthma 201047822–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuther DA, Weiss ST, Sutherland ER. Obesity and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:112–119. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-231PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shawwa BA, Al-Huniti NH, DeMattia L, Gershan W. Asthma and insulin resistance in morbidly obese children and adolescents. J Asthma. 2007;44:469–473. doi: 10.1080/02770900701423597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson PH, Williams LW, Benjamin DK, Barnato AE. Obesity, inflammation, and asthma severity in childhood: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2004. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:381–385. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Lai HJ, Roberg KA.et al. Early childhood weight status in relation to asthma development in high-risk children J Allergy Clin Immunol 20101261157–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luder E, Melnik TA, DiMaio M. Association of being overweight with greater asthma symptoms in inner city black and Hispanic children. J Pediatr. 1998;132:699–703. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart KA, Higgins PC, McLaughlin CG.et al. Differences in prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of asthma among a diverse population of children with equal access to care: findings from a study in the military health system Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010164720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson CC, Clark S, Camargo CA, Jr, MARC Investigators Body mass index and asthma severity among adults presenting to the emergency department. Chest. 2003;124:795–802. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo GJ, Plaza V. Body mass index and response to emergency department treatment in adults with severe asthma exacerbations: a prospective cohort study. Chest. 2007;132:1513–1519. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strine TW, Balluz LS, Ford ES. The associations between smoking, physical inactivity, obesity, and asthma severity in the general US population. J Asthma. 2007;44:651–658. doi: 10.1080/02770900701554896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo CA, Jr, Sutherland ER, Bailey W.et al. Effect of increased body mass index on asthma risk, impairment and response to asthma controller therapy in African Americans Curr Med Res Opin 2010261629–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belamarich PF, Luder E, Kattan M.et al. Do obese inner-city children with asthma have more symptoms than nonobese children with asthma Pediatrics 20001061436–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantisira KG, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, Fuhlbrigge AL, Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group Association of body mass with pulmonary function in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) Thorax. 2003;58:1036–1041. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.12.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnick C, Coleman KJ, Black MH.et al. Cohort Profile: The KPSC Children's Health Study, a population-based study of 920 000 children and adolescents in southern California Int J Epidemiol 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith N, Coleman KJ, Lawrence JM.et al. Body weight and height data in electronic medical records of children Int J Pediatr Obes 20105237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL.et al. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts Am J Clin Nutr 2009901314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS.et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development Vital Health Stat 2002111–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Technical Report Series 894: Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organization, Geneva 2000; ISBN 92-4-120894-5. [PubMed]

- U.S. Bureau of Census Census 2000 surname list. <http://www.census.gov/genealogy/www/data/2000surnames/index.html> (Washington DC, 2009).

- Fiscella K, Fremont AM. Use of geocoding and surname analysis to estimate race and ethnicity. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1482–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word DL, Perkins RC.Building a Spanish surname list for the 1990's—A new approach to an old problemU.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC; 1996. Technical Working paper No.13. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan CW, Brown BD, Bentley B.et al. Variability in childhood asthma and body mass index across Northern Plains American Indian communities J Asthma 201047496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom J, Morley EJ, Sasso P, Sinert R. Body mass index and pediatric asthma outcomes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:569–571. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181b4f639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]