Primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL) is an extremely rare tumor (<1% incidence) and is often confused with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Standard management of PPL involves chemotherapy and radiotherapy, yet uncertainty regarding the diagnosis of a mass in the pancreatic head usually results in surgical resection as well. We describe a 68-year-old man with a pancreatic head mass who underwent successful pancreaticoduodenectomy. The final pathology report revealed an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive, diffuse, and large B-cell lymphoma, with 7 of 8 nodes positive for lymphoma. He underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone (R-CHOP).

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old man presented to an outside hospital after feeling ill for a week, with complaints of nausea and abdominal pain. He appeared jaundiced and was transferred to the emergency department at our institution for further workup and evaluation. His past medical history was significant for gastroesophageal reflux disease and rheumatoid arthritis. He also had a past history of smoking but had quit in 1967.

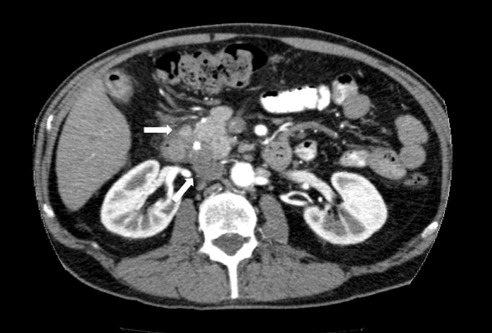

On physical examination at our institution, he had diffuse jaundice, with scleral icterus and mild tenderness in the epigastrium. His laboratory values, in particular his liver profile, were of concern: total bilirubin, 8.4 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase (AST), 203 IU/L; alanine transaminase (ALT), 300 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 909 IU/L. His CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen were both within normal limits. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a 2-cm hyperdense lesion in the pancreatic head, consistent with pancreatic cancer (Figure 1). The surrounding soft tissue changes could have represented either adenopathy (peripancreatic adenopathy; Figure 2) or tumor spread in the liver with possible involvement of the hepatic artery (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

CT image reveals a 2-cm hyperdense lesion in the pancreatic head.

Figure 2.

Image reveals soft tissue changes indicative or peripancreatic adenopathy or tumor spread.

Figure 3.

CT image reveals a mass with possible involvement of the hepatic artery.

At that point the patient underwent endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). EUS revealed a 2.7-cm mass in the pancreatic head that encased the common bile duct. Two lymph nodes were of concern (a celiac node and a peripancreatic node), so we biopsied both nodes. Additionally, we obtained brushings of the duct and left a stent in place to relieve the patient's obstructive jaundice. The pathology reports from both the brushings and the lymph node biopsies were negative for malignancy.

After discussion at our institution's multidisciplinary tumor board meeting and with the patient, we decided to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy with the potential for pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) as well. Laparoscopic ultrasonography did not reveal any evidence of malignancy in the liver, and the tumor did not involve the hepatic artery. Therefore, we performed the Whipple procedure without complication. The patient had an uneventful hospitalization and was discharged home.

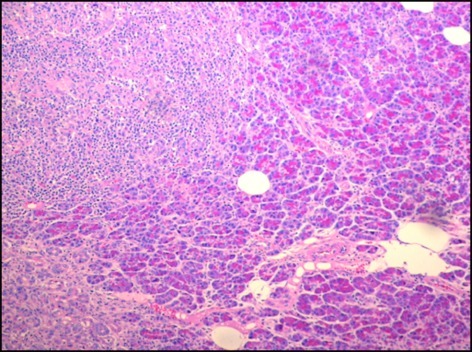

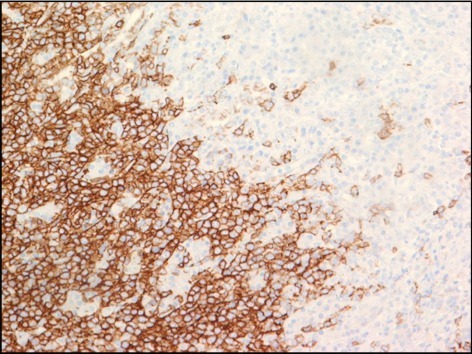

The final pathology report of the surgical specimen was significant for an EBV-positive, diffuse, large B-cell lymphoma (Figure 4). In addition, 7 of the 8 nodes were positive for lymphoma. The specimen was also positive for immunohistochemical markers cluster of differentiation 20 (CD 20) (Figure 5), CD30, EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) per in situ hybridization (ISH), and mutated melanoma-associated antigen (MUM) 1; it was dimly positive for B-cell lymphoma (BCL) 2 and BCL6; and it had a Ki67 of 70%. The specimen was negative for CD5, CD10, CD 23, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), and kappa and lambda mRNA per ISH.

Figure 4.

Histologic (hematoxylin and eosin stain) image reveals a tumor (upper left) infiltrating normal pancreatic parenchyma (magnification 4×).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical test against CD 20 reveals strong membranous staining of tumor cells infiltrating a normal pancreatic parenchyma.

Postoperatively, the patient underwent more staging tests. His lactate dehydrogenase level and his beta-2 microglobulin level were both elevated. His human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis test results were negative. Repeat CT revealed increasing lymphadenopathy of his retroperitoneal nodes (Figure 6), along with new lymphadenopathy of the mediastinal and obturator regions (Figure 7). His disease was diagnosed as stage IIIA, international prognostic index (IPI) 3. He was started on R-CHOP chemotherapy and underwent 6 cycles. At his last clinic visit, his lymphoma was in remission.

Figure 6.

CT image reveals lymphadenopathy of retroperitoneal nodes.

Figure 7.

CT image reveals obturator lymphadenopathy.

DISCUSSION

Of all pancreatic malignancies, PPL accounts for only 1%–2%; the diffuse, large, B-cell lymphoma subtype is the most common PPL.1 This subtype is considered a subtype of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), but it is rare for NHL to manifest in this manner. NHL typically manifests in the nodes; extranodal NHL occurs in only 20%–30% of NHL patients. Most cases of extranodal NHL originate in the gastrointestinal tract; only 0.6% of cases of NHL originate in the pancreas.2

Often PPL is difficult to differentiate from other pancreatic malignancies. Some clues pointing to PPL (instead of adenocarcinoma) include an abdominal mass with a lack of jaundice, constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fever, and night sweats),2 an elevated LDH level, an elevated beta-2 microglobulin level, and a normal serum CA 19–9.1 Size is another clue: PPL lesions are typically larger than 6 cm. Surrounding lymphadenopathy is common with any lymphoma: however, this feature would not exclude adenocarcinoma.2

Diffuse, large, B-cell lymphoma of the pancreas can manifest in two different ways on CT: (1) the pancreas has a similar appearance to pancreatitis, with an infiltrative mass and peripancreatic fat stranding1 or (2) the pancreas seems to have a well-circumscribed tumor.1 In both CT presentations, peripancreatic lymphadenopathy can be significant, often enough to obscure the borders of the pancreas.2

A tissue biopsy is necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Initially the biopsy can be performed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Although FNA is the most common initial biopsy method, it frequently results in both false-negative and false-positive results and often does not provide enough information to classify the lymphoma. More tissue is needed for flow cytometric analysis, which can make the diagnosis more accurately.3 Another option for obtaining a tissue sample is CT-guided biopsy, which has the advantage of being minimally invasive.2 Alternatively, a laparoscopy or laparotomy can be performed to biopsy the pancreatic mass or lymph nodes. If lymphoma is suspected, a biopsy specimen could also be obtained from bone marrow.2

Currently surgery has been used as a diagnostic modality only for PPL, especially to obtain biopsy and tissue samples, but also to relieve biliary obstruction. Surgery is necessary when other methods fail to diagnose PPL. Most chemotherapy consists of CHOP1 and sometimes R-CHOP. Despite initial clinical improvement, chemotherapy is fraught with a high disease recurrence rate. Other chemotherapy regimens have similar success rates in PPL patients, although CHOP is most commonly used. More research needs to be done to find a better chemotherapy regimen for preventing late recurrence.4

Considering the success of treating other abdominal lymphomas with surgical resection, it should also be considered in patients with diffuse, large, B-cell lymphoma of the pancreas.1 Some, though limited, retrospective evidence suggests that patients treated with both chemotherapy and surgery (as compared with chemotherapy alone) have an improved 5-year survival rate—regardless of the stage, grade, or location of disease. Subsequent to a literature review for the years 1951 through 2006, Battula identified 15 NHL patients treated with surgical resection who had at least 36 months of follow-up. They reported a 100% response rate and a 94% survival rate during this time period.5 An article by Behrns showed some evidence that an initial surgical resection, when coupled with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, was associated with increased long-term survival of PPL patients.6 However, one needs to take into account the complications of the Whipple procedure, including—but not limited to—hemorrhage, abscess formation, anastomotic leak, delayed gastric emptying, pancreatitis, liver infarction, GERD, and wound infections.7

CONCLUSION

Because PPL is a rare clinical entity, the literature is still inconclusive about its ideal surgical management. In patients like ours, surgery may be necessary to obtain a definitive diagnosis; surgery may also be associated with increased survival. But the Whipple procedure has many inherent complications, which could be avoided with a preoperative tissue diagnosis. However, surgical resection for limited disease may increase survival and decrease recurrence rates. More work needs to be done to determine whether the Whipple procedure should be the standard of care or whether chemotherapy should be the sole treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mary Knatterud for her assistance with editing.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liakakos T, Misiakos EP, Tsapralis D, et al. : A role for surgery in primary pancreatic B-cell lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2:167, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salvatore JR, Cooper B, Shah I, Kummet T: Primary pancreatic lymphoma: a case report, literature review, and proposal for nomenclature. Med Oncol 17:237–247, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nayer H, Weir EG, Sheth S, Ali SZ: Primary pancreatic lymphomas: a cytopathologic analysis of a rare malignancy. Cancer Cytopathol 102(5):315–321, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grimson PS, Chin MT, Harrison ML, Goldstein D: Primary pancreatic lymphoma—pancreatic tumours that are potentially curable without resection, a retrospective review of four cases. BMC Cancer 6:117–125, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Battula N, Srinivasan P, Prachalias A, et al. : Primary pancreatic lymphoma: diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Pancreas 33(2):192–194, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Behrns KE, Sarr MG, Strickler JG: Pancreatic lymphoma: is it a surgical disease? Pancreas 9(5):662–667, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chew DK, Attiyeh FF: Experience with the @hipple procedure in a university affiliated community hospital. Am J Surg 174:312–315, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]