Abstract

Brain correlates of the sense of agency have recently received increased attention. However, the explorations remain largely restricted to the study of brains in isolation. The prototypical paradigm used so far consists of manipulating visual perception of own action while asking the subject to draw a distinction between self- versus externally caused action. However, the recent definition of agency as a multifactorial phenomenon combining bottom-up and top-down processes suggests the exploration of more complex situations. Notably there is a need of accounting for the dynamics of agency in a two-body context where we often experience the double faceted question of who is at the origin of what in an ongoing interaction. In a dyadic context of role switching indeed, each partner can feel body ownership, share a sense of agency and altogether alternate an ascription of the primacy of action to self and to other. To explore the brain correlates of these different aspects of agency, we recorded with dual EEG and video set-ups 22 subjects interacting via spontaneous versus induced imitation (II) of hand movements. The differences between the two conditions lie in the fact that the roles are either externally attributed (induced condition) or result from a negotiation between subjects (spontaneous condition). Results demonstrate dissociations between self- and other-ascription of action primacy in delta, alpha and beta frequency bands during the condition of II. By contrast a similar increase in the low gamma frequency band (38–47 Hz) was observed over the centro-parietal regions for the two roles in spontaneous imitation (SI). Taken together, the results highlight the different brain correlates of agency at play during live interactions.

Keywords: agency, hyperscanning, EEG, imitation, social interaction

Introduction

A growing body of neuroimaging studies explore agency as the capacity to locate the origin of an action in the self. Yet, if we leave a solipsistic view of individual agency, we should take account of the fact that human agency is to a large extent determined by social factors (de Jaegher and Froese, 2009). Far from being limited to know whether an action comes from self or from an external source, we usually have to determine what caused the action to be ours in an interactive context. Notably there is a need of accounting for the dynamics of agency in a two-body context where we often experience the double faceted question of who is at the origin of what in an ongoing interaction. Using dual EEG and video set-ups, the aim of the present study was to explore the brain correlates of such a phenomenon.

Philosophers (Wittgenstein, 1958; de Vignemont and Fourneret, 2004; Gallagher, 2007; de Vignemont, 2011) have argued that agency is too complex an experience to be described as a unitary phenomenon. When, through our proprioception, we feel our body moving, we ascribe without any doubt the ownership of the action to our body (Wittgenstein, 1958). Vision, however, can affect the proprioceptive message about body knowledge, as demonstrated by the rubber hand illusion: indeed, watching a rubber hand being stroked together with the subject's own unseen hand causes the rubber hand to be ascribed as part of the subject's body (Botvinick and Cohen, 1998; Ehrsson et al., 2005; Tsakiris and Haggard, 2005). Thus, a multisensory integration is suggested to be the underlying mechanism of body ownership. Though multisensory, the experience of body ownership does not depend on voluntary movement. Even when passively moved, our arm movement belongs to our body and is felt as such. Body ownership accompanies all actions, passive, automatic as well as voluntary ones. By contrast, the sense of being at the origin of the action is restricted to voluntary actions.

Beyond a first distinction between the sense of agency and the sense of ownership (Gallagher, 2000; Marcel, 2003), a later distinction between a feeling and a judgment of agency and a feeling and judgment of ownership was then added to stress the multifactorial aspect of agency, seen as a cluster of subjective experiences, feelings and attitudes (Synofzik et al., 2008). Within this framework, the long-lasting debate of whether the two aspects of our self-awareness have related or independent mechanisms is revisited. For example, a recent fMRI study found no shared activations between body ownership and agency: while activations in midline cortical structures were associated with a sense of body ownership, activity in the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA) was linked to the sense of agency (Tsakiris et al., 2010). In addition to pre-SMA and SMA (Farrer et al., 2003; Yomogida et al., 2010; Nahab et al., 2011), insula (Farrer and Frith, 2002; Farrer et al., 2003), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Fink et al., 1999) and precuneus (Ruby and Decety, 2001; Farrer and Frith, 2002) were also found to be involved in the sense of agency. But a major emphasis has been posed on the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) as the neural basis of the sense of agency. Two among the three existing meta-analyzes devoted to agency (Decety and Lamm, 2007; Spengler et al., 2009) have designed an a priori region of interest in TPJ. There are several reasons to attribute a great importance to TPJ, from “the alien hand” syndrome (Bundick and Spinella, 2000) or limbs misattributions (Daprati et al., 2000) caused by lesions of these regions, to the involvement in action awareness (Frith et al., 2000) and perspective taking (Ruby and Decety, 2003; Thirioux et al., 2010).

Recently, however, Moore and coworkers (Moore et al., 2010) have argued that the TPJ seems more involved in the feeling of non-agency than in a sense of self-agency. This consideration leaves the possibility that the sense of self- versus other-agency could be supported by partially different neural mechanisms. A third meta-analysis, led by our team, started from a definition of sense of agency instead of starting from a definition of regions of interest (Sperduti et al., 2011). Using activation likelihood estimation (ALE) method, the meta-analysis revealed dissociation between brain regions involved in self and external agency ascription. More specifically, TPJ activity appeared to be more present in external- than in self-agency ascription. This may be due to the tasks chosen, all derived from the comparator model (Jeannerod, 2003b). In these tasks, brain effects of a congruent visual feedback of self-movements are compared to brain effects of a non-congruent visual feedback. The task is a solitary task comparing the visual and kinesthetic feedbacks of an individual in two experimental conditions.

A challenger to this indirect test of other's agency is the immersion of subjects in a social context of interaction. Interacting freely via imitation provides a test-case of the multifactorial aspects of agency in everyday social life. In Jeannerod' s words, “an observer monitoring an action performed by someone else is never far from also being the agent of that action” (Jeannerod, 2003a). Further, an observer matching the action performed by someone else feels this action as its own, and gets a sense of being also the agent of that action. Body ownership and sense of self- and other-agency are shared. However, a cognitive component of agency will differ in the two agents: action primacy will be ascribed to self by the first author of the action and to other by the imitator. Such an asymmetry may generate in the first author a rewarding sense of exerting a power on an audience. For instance, young infants show a marked visual preference for an imitative experimenter compared to a non-imitative one, even when both behave contingently (Meltzoff, 1990). In adults, being imitated generates an increase in positive behavior toward the imitator from the part of the model (Ashton-James et al., 2007). Similarly, children with autism address positive social signals like smiles, eye contact and touch to their imitator (Nadel et al., 2000; Nadel, 2006). There is thus also a benefit to be an imitator. Switching role from model to imitator like preverbal children do in the course of an imitative sequence (Nadel and Baudonnière, 1982; Nadel and Butterworth, 1999) could be understood as a way to exchange reward while framing imitation as an interactive pattern of reciprocal initiations and responses. Such interactive pattern is still observable in adults and generates the involvement of brain areas concerned with social interaction and cognition (Guionnet et al., 2011). Many other cases in the domain of social interaction, such as joint attention/activity and social coordination are well described by a shared sense of agency of action to which may be added an opposite ascription of primacy of action. Therefore, there is a need to take seriously the role of social interaction in individual agency (Decety and Lamm, 2007; David et al., 2008; de Jaegher and Froese, 2009) and to study the underlying brain dynamics in a social context.

The hyperscanning methodology constitutes a relevant tool to explore real-time social phenomena (Montague et al., 2002; Hasson et al., 2004; Babiloni et al., 2006). Hyperscanning methods have been recently used to explore interpersonal coordination (Tognoli et al., 2007; Lindenberger et al., 2009), inter-brain connectivity-related to decision-making (Astolfi et al., 2010), or inter-brain synchronization during imitative interaction (Dumas et al., 2010), but so far, to our own knowledge, they have not been devoted to study self- versus other-agency. Combining hyperscanning methodology with instantaneous EEG recording seems well adapted, given its high temporal resolution, to measure brain dynamics underlying emergent processes such as ascription of action primacy and shared sense of agency. In view of previous studies revealing that brain regions, and even single neurons, do not generally display pure oscillations but oscillate at multiple frequencies, and that several rhythms can coexist in the same area or interact among different structures (Llinas, 1988; Buzsaki and Draguhn, 2004; Steriade, 2006; Kopell et al., 2010), a holistic intra-brain analysis approach along the spectral dimension was privileged to study largely unexplored aspects of agency. Our imitation design also appears to be relevant for such an exploration. Indeed, it allows compare brain activities associated with two roles (model and imitator) in two conditions: a spontaneous imitation (SI) condition where the roles of model and imitator are freely negotiated by the partners themselves, and an induced imitation (II) condition where the repartition of roles is instructed (please imitate the gestures you see/please move your hands in order to be imitated). To approach the potentially different processes in play for the two roles in the two conditions, contrasts were designed, based on hypotheses drawn from the EEG literature or from our own previous results. Contrasts aimed first at controlling for action and for action observation, second at controlling for self- and other-ascription of agency in II, and third at testing whether similar components of self- and other-ascription of agency are to be found in the SI condition. In view of the EEG/MEG literature, we anticipated decrease of oscillations in the mu (8–13 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) frequency ranges over the sensorimotor cortex under conditions of observation and execution of movements (Cochin et al., 1999; Pineda, 2005; Lepage and Theoret, 2006; Oberman et al., 2007; Calmels et al., 2008; Muthukumaraswamy and Singh, 2008). Concerning the two roles of model and imitator, we foresighted that the social context should modulate neural dynamics given that in our previous study (Dumas et al., 2010) inter-brain synchronizations were found in different frequency bands for induced compared to SI conditions. We expected differential EEG oscillations for the two roles during the induced condition of imitation where the roles are externally assigned. By contrast, we expected similar oscillatory activity within several frequency bands in the SI condition where partners negotiate roles with a sense of being each an actor of the negotiation. More specifically, we took account of previous studies documenting the involvement, in agency or ownership ascription, of gamma-band (30–70 Hz) oscillations over the centro-parietal and temporal regions (Pavlova et al., 2006; Kanayama et al., 2009; Pavlova et al., 2010). We thus investigated whether rapid oscillations in these regions may discriminate the two partners as a function of action primacy ascribed to self, to other, or to both.

Of course we do not claim that all mechanisms and interactions involved in the complex phenomena studied are assessed in the contrasts computed, but at least the contrasts chosen will allow start exploring the terra incognita of agency within a social context.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-two healthy adults of mean age 24.5 years (SD = 2.8) forming 11 unacquainted pairs (five female-female and six male-male pairs) participated in the study. All of them were right-handed. They had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and none of them reported a history of psychiatric or neurological diseases. The participants had given their written informed consent according to the declaration of Helsinki and the chart of the local ethics committee. The subjects were paid for their participation.

Apparatus and setting

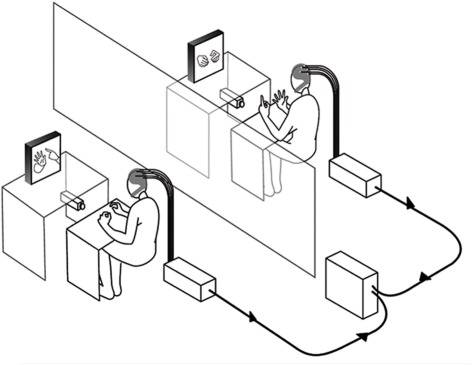

The experiment was conducted in two separate laboratory rooms. Figure 1 describes the design and equipment that were similar to the double-video system designed by Nadel and colleagues for their developmental studies of sensitivity to social contingency in infants (Nadel et al., 1999; Soussignan et al., 2006), except that a dual EEG recording system was added to the setup. Two synchronized DV video cameras filmed the hand movements of each partner (see Video S1). Each participant could see the partner's hands through 21 inches. TV monitors, the forearms lying on a small table to prevent arm and neck movements. The monitoring of the experiment was performed in a third room where two computers managed both the dual EEG and video recordings.

Figure 1.

Apparatus and experimental setting of the double-video system and dual-EEG recording.

Procedure

Table 1 describes the experimental schedule. The experiment was divided into two blocks, each composed of four runs. Each run began with a 15 s no view no motion (NVNM) baseline where participants were asked to fix a blank screen without moving. Depending on the runs, NVNM was directly followed by an observation condition (run 1) or by another 15 s baseline no view motion (NVM) for the three experimental runs of imitation. During the NVM baseline, subjects were asked to move their hands continuously while looking at the blank screen.

Table 1.

Experimental schedule.

| Condition (Block 1) | NVNM + library of intransitive movements (LIHM) | NVNM + NVM + spontaneous imitation (SI) | NVNM + NVM + induced imitation (II), subject 1: imitator, subject 2: model | NVNM + NVM + induced imitation (II), subject 2: imitator, subject 1: model |

| PAUSE: 10 MIN | ||||

| Condition (Block 2) | NVNM + library of intransitive movements (LIHM) | NVNM + NVM + spontaneous imitation (SI) | NVNM + NVM + induced Imitation (II), subject 2: imitator, subject 1: model | NVNM + NVM + induced imitation (II), subject 1: imitator, subject 2: model |

| Duration | 15 s + 1 min 30 s | 15 s + 15 s +1 min 30 s | 15 s + 15 s + 1 min 30 s | 15 s + 15 s + 1 min 30 s |

The observation condition consisted in the observation of a library of intransitive hand movements (LIHM) composed of 20 meaningless hand/finger movements continuously executed by an actor. In the SI condition, the participants were proposed to move their hands continuously and to imitate their partner whenever they would like it. This led to spontaneously coordinate two roles: imitate and be imitated. In the II condition, subject 1 (imitator) was asked to imitate continuously the hand movements of subject 2 (model) who was told to move hands freely, and vice-versa for the other run, with a counterbalanced order in block 2 (see Table 1).

Contrasts

Contrasting NVM to NVNM allows controlling for motor activity to which is added a sense of self-agency. Contrasting LIHM to NVNM leads to control for action observation to which is added a sense of other-agency. In a second round, contrasting the role of induced imitator [Im (II)] to NVM will consist in comparing an instructed task of “observe and match” the partner's action with a motor task attributed to self: this would lead to document other-agency and action primacy attributed to other while motor activity attributed to self is controlled. Of course the movement is not the same in the two conditions and it can be argued that the difference attributed to agency can be explained by mere motor difference. Nevertheless, our imitation condition generates different results compared to motor only condition. Moreover, it has been shown that the pattern of finger movement sequences has low influence on the related inter-regional brain activity (Calmels et al., 2008) and was restricted to spectral power decreases in the alpha band over centro-parietal regions (Manganotti et al., 1998).

Contrasting the role of induced model [Mod (II)] to NVM consists in comparing an instructed task of “initiate an action to be imitated by the other” with a motor task attributed to self. This would lead to document action primacy attributed to self, while the other components are controlled.

In a third round, contrasting, respectively, the role of spontaneous imitator [Im (SI)] to NVM and the role of spontaneous model [Mod (SI)] to NVM will test whether ascription of action primacy to other or to self differ when roles are freely negotiated compared to instructed roles. Finally, the role of model and of imitator will be contrasted according to the imitation condition.

Dual EEG data-acquisition

The neural activities of the two participants were simultaneously recorded with a dual-EEG recording system. It was composed of two Acticap helmets with 32 active electrodes arranged according to the international 10/20 system. We modified the helmets in order to cover at best the occipito-parietal regions. Four electrodes T7, T8, CP9, and CP10 were rejected due to artifacts. Ground electrode was placed on the right shoulder of the subjects and the reference was fixed on the nasion. The impedances were maintained below 10 kΩ. Data acquisition was performed using a 64-channels Brainamp MR amplifier from the Brain Products Company (Germany). Signals were analog filtered between 0.16 Hz and 250 Hz, amplified and digitalized at 500 Hz with a 16-bit vertical resolution in the range of ±3.2 mV.

Recorded behavioral analysis

The coding of the recordings used the ELAN software (Grynszpan, 2006; Sloetjes and Wittenburg, 2008) allowing a simultaneous presentation of the frames from the two partners, together with a recording of time (latency, duration) and occurrence of behavioral events. Digitalized videotapes of each participant were synchronized and a frame-by-frame analysis was conducted in order to extract the periods of imitation as well as the roles defining who was imitating (Imitator) and who was imitated (Model). Imitation was assessed when the hand movements of the two partners showed a similar morphology (describing a circle, waving, swinging…) and a similar direction (up, down, right, left…). For each imitative episode, the individual who started a hand movement followed by the partner was labeled the “model,” and the follower was labeled the “imitator.” A substantial inter-coder agreement was assessed through kappa coefficients (>0.80). Imitation epochs were on average 6 s long (SD = 4 s) and represented 64.69% of the interaction time (for details, see Dumas et al., 2010).

EEG artifacts

The correction of eye blink artifacts in the EEG data was performed using a classical principal component analysis (PCA) filtering algorithm (Wallstrom et al., 2004a,b). We used 800 ms windows with 400 ms of overlap. For each window, a PCA was performed on the raw signal and all the PCA-components were compared to an estimation of the electro-oculogram (EOG) computed from the difference between the mean of the raw channels FP1 and FP2 and the nasion reference. If the correlation between the reconstructed EOG signal and each PCA-component exceeded an adaptive threshold, the eigenvalue-related to the component was fixed to zero. Then the converted EEG signal can be reconstructed by using the inverse solution of the PCA. The adaptive threshold was proportional to the standard deviation of the considered ith component divided by those of the current window signal:

| (1) |

where σ(ci) stands for the standard deviation of the ith component of the PCA and σ(∑ici) is the standard deviation of the signal. EEG signals were then controlled visually another time in order to eliminate muscular artifacts. These EEG segments were excluded from the analysis and, in order to avoid border artifacts induced by their suppression, we smoothed the joints by a convolution with a half-Hanning window of 400 ms.

EEG analysis

Instead of using selected large frequency bands, we have covered the whole spectrum (0–48 Hz) with 1 Hz frequency bins, which accounts at best for the variability in frequency distributions across subjects.

Following corrections, EEG data were re-referenced to a common average reference (CAR). Then a fast fourier transform (FFT) was applied on 800 ms windows, smoothed by Hanning weighting function and half-overlapping across either the whole trials in the case of contrasts between conditions or the segments corresponding to the behavioral analysis as Imitator or Model in the SI condition.

Statistical analyzes

Significance of the differences in all contrasts was established using a non-parametric cluster randomization test across spatial and spectral domains (Nichols and Holmes, 2002; Maris and Oostenveld, 2007; Maris et al., 2007). This test effectively controls the false discovery rate in situations involving multiple comparisons by clustering neighboring quantities that exhibit the same effect. For the amplitude analysis, the neighborhood was univariate across space (adjacent electrode over the scalp) and frequencies (side-by-side frequency bins). The permutation method provides values whose t statistics exceed a given critical value when comparing two conditions value by value. In order to correct for multiple comparisons, neighbor values exceeding the critical value were considered as a member of the same cluster. The cluster-statistic (CS) was taken as the sum of t values in a given cluster. Evaluating the CS distribution through 1000 permutations controlled the false discovery rate (Pantazis et al., 2005). Each permutation represented a randomization of the data between the two conditions and across multiple subjects. For each permutation the CSs were computed by taking the cluster with the maximum sum of t statistics. The threshold controlling the family wise error rate (FWER) was determined according to the proportion of the randomization null distribution exceeding the observed maximum CS (Monte Carlo test). Clusters containing less than three different electrodes or three different frequency bins were excluded. We used a threshold critical value of |2σ|.

Results

Table A1 in the appendix data summarizes all contrasts computed.

Control conditions

Execution of movement [NVM–NVNM]

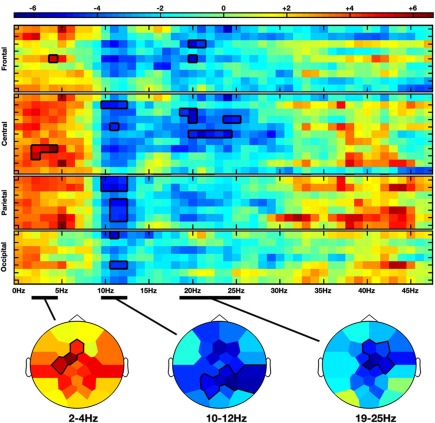

Moving hands increased the delta band amplitude in the frontal (2–4 Hz; Fz, FC1, C3; CS = 28.3, p < 0.05) region, whereas decrease in the alpha-mu and beta bands was, respectively, observed in the parieto-central (10–12 Hz; CP2, CP6, P3, PZ, P4, P8, PO1; CS = −68.4, p < 0.05) and fronto-central (19–25 Hz; Fz, F4, FC2, Cz, C4; CS = −66.2, p < 0.05) regions (see Figures 2 and 4A).

Figure 2.

Non-parametric clustering analysis applied to the NVM versus NVNM contrast. Rows and columns represent, respectively, electrodes and frequency bins. Electrodes are grouped by anatomical region. The color stands for the t-values calculated between the two conditions with the subject average fast Fourier transform (FFT) components. Topographies at the bottom represent the mean t-values across the frequency range of the considered clusters. Statistical clusters are outlined in thick black lines for both representations. NVM, no view motion; NVNM, no view no motion.

Figure 4.

Other agency and delta frequency band effects. LIHM versus NVNM (A) and Imitator in II versus NVM (B) show a similar increase of delta activity (>0–5 Hz) mostly over the right central region. The color stands for the mean t-values across the frequency range of the considered clusters. Statistical clusters are outlined in thick black lines for both representations. For abbreviations, see previous figures. LIHM, library of intransitive hand movements.

Passive observation of movement [LIHM–NVNM]

Passive observation of hand movements (LIHM) induced an increase in delta and theta amplitudes in the fronto-central (1–5 Hz; FC1, FC2, C4, CP6; CS = 184.4, p < 0.001) and parietal (6–8 Hz; CP6, P7, P3, Pz, P4, PO1; CS = 223.7, p < 0.001) regions (see Figure 3A), respectively, and a decrease of high alpha-mu rhythm in the centro-parietal regions (11–13 Hz; CP1, CP2, P3, PO1; CS = −123.0, p < 0.001).

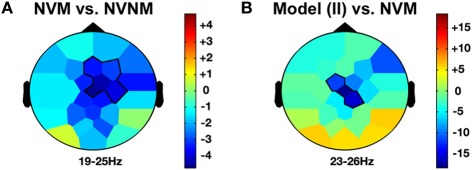

Figure 3.

Self-agency and beta frequency band effects. NVM versus NVNM (A) and Model in II versus NVM (B) show a similar decrease of the beta activity (19–26 Hz) across the right fronto-central regions. The color stands for the mean t-values across the frequency range of the considered clusters. Statistical clusters are outlined in thick black lines for both representations. II, induced imitation. For other abbreviations, see Figure 2.

Induced imitation condition

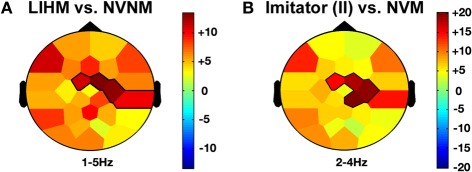

Induced imitator [Im (II)–NVM]

When the role of induced imitator was contrasted with solitary execution of movement, amplitude increased in the delta band over the right fronto-central regions (2–4 Hz; FC1, FC2, C4, CP2; CS = 136.8, p < 0.001; see Figure 3B). There was also a decrease of alpha-mu activity in the parietal region (12–14 Hz; CP1, CP2, P3; CS = −106.6, p < 0.001).

Induced model [Mod (II)–NVM]

When the role of induced model was contrasted with solitary execution of movement, an increase of amplitude was observed in the theta band over centro-parietal regions (4–8 Hz; CP1, P3, Pz, PO1; CS = 131.4, p < 0.001; see Figure 5D) whereas a decrease in alpha-mu rhythm was found over parietal region (11–14 Hz; CP1, CP2, P3, Pz, P4, P8, PO1; CS = −244.6, p < 0.001). There was also a decrease of activity in the beta band over the fronto-central regions (23–26 Hz; FC1, Cz, CP2; CS = −135.6, p < 0.001; see Figure 4B).

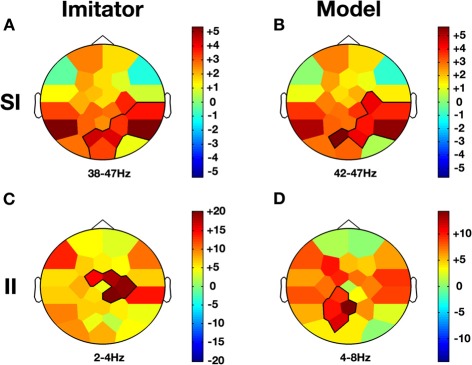

Figure 5.

Co-ownership and low/high frequency bands effects. Compared to baseline (NVM), Imitator and Model show a similar increase in gamma activity (38–47 Hz) in parietal regions during SI while this effect was not present in II (A and B). However, there is an increase for both delta/theta activity (2–8 Hz) in II but topographies are different. While this change occurs in the right central region for the Imitator (C), it is more localized over the precuneus region for the Model (D). The color stands for the mean t-values across the frequency range of the considered clusters. Statistical clusters are outlined in thick black lines for both representations. For abbreviations, see previous figures. SI, spontaneous imitation.

Spontaneous imitation condition

Spontaneous imitator [Im (SI)–NVM]

When a participant was freely imitating compared with solitary execution of movement, gamma amplitude increased in the centro-parietal region (38–47 Hz; CP6, P4, P8, PO1, Oz, PO2; CS = 130.2, p < 0.001; see Figure 5A). There was also a decrease in the alpha-mu band over the parietal region (10–14 Hz; Pz, P4, P8, Oz, PO2; CS = −63.4, p < 0.05).

Spontaneous model [Mod (SI)–NVM]

When a participant was freely initiating an imitation compared with solitary execution of movement, gamma amplitude increased over centro-parietal regions (42–47 Hz; C4, CP6, P4, P8, PO1, PO2; CS = 117.0, p < 0.001; see Figure 5B) whereas a decrease was observed in the alpha-mu band over the parietal region (10–14 Hz; Pz, P4, P8, PO1, Oz, PO2; CS = −73.4, p < 0.05).

Influence of the social context

The two roles of model and imitator were contrasted in the two conditions to evaluate the influence of the social context.

Influence of the social context regarding the role of imitator [Im (SI)–Im (II)]

A decrease in the theta/alpha band amplitude was found in occipito-parietal regions (4–9 Hz; CP6, P4, P8, PO9, Oz, PO2; CS = −68.0 p < 0.05).

Influence of the social context regarding the role of model [Mod (SI)–Mod (II)]

No difference was found between the two conditions.

Discussion

Using reciprocal imitation as a test-case for the multifactorial account of agency, we aimed at delineating the brain dynamics-related to different components of agency as they emerge from a live interaction between two persons. In this situation, one has to differentiate who generated first the action imitated, who is in control of the imitation, and who feel the action as one's own action. A simultaneous EEG record of dyads engaged in different imitative conditions allowed us to use contrasts providing a few answers to these questions. A few answers only can be provided, since, as already stressed in the introduction, the whole mechanisms and interactions included into the complex phenomenon studied cannot be assessed via the computed contrasts. The contrasts were chosen so as to control for action and action observation, then for self- and other-ascription of agency in the externally driven condition of imitation. Based on the results of the controls, we investigated if similar components of self- and other- ascription of agency were present in the SI condition. Were our controls strong enough? It may be argued that the movement is not the same in the two conditions: this is only partly true (i.e., the number of intransitive gestures that do not imply to link hands is limited) and in any case the pattern of finger movement sequences has low influence on the related-inter-regional brain activity (Calmels et al., 2008). It may also be questioned whether the difference attributed to agency ascription could not be explained by mere visual or motor difference within contrasts. This question can be answered using the multifactorial two-step account of agency proposed by Synofzik et al. (2008). Indeed, our design offers the example of a social situation where there are strong similarities between what is seen and what is acted, although what is seen is what the other does and what we feel as ours is the action we are doing but not seeing. The challenge is, beyond shared feeling of ownership and agency, to process conceptually so as to correctly ascribe the primacy of agency to self or to other. Far from resulting uniquely from action observation or action execution, such challenge is the genuine byproduct of a cross-coupling of observation and action between two individuals: accordingly our imitation condition generates different results compared to motor only condition.

Let us summarize what was common to all conditions analyzed. As predicted and widely documented (Cochin et al., 1999; Pineda, 2005; Lepage and Theoret, 2006; Oberman et al., 2007; Calmels et al., 2008; Muthukumaraswamy and Singh, 2008), we found a decrease of oscillations in the alpha-mu over the sensorimotor cortex under conditions of observation and execution of movements as well as in all observation/execution related contrasts in a common frequency range of 10–14 Hz. These results are in line with the proposal that mu rhythm desynchronization acts as an index of perception-action coupling (Pineda, 2005; Oberman et al., 2008).

Beyond these similarities, strong differences appeared. Action production and observation differed for other frequencies: beta activity specifically decreased over the fronto-central regions during action production contrasted with rest (NVM vs. NVNM), while delta/theta-frequency band increased during action obser vation contrasted with rest (LIHM vs. NVNM) over the central region. Differences concerning these frequency bands also appeared for the roles of imitator and model in the condition of II.

Self- and other- ascription of action primacy

Contrasting brain activity when the subject was the model versus when moving hands without vision (NVM baseline) revealed modulation in alpha-mu and beta frequency bands like for action production (NVM vs. NVNM) but not in delta/theta-frequency unlike in action observation (LIHM vs. NVNM). In this line, there is increasing evidence that beta oscillations underpin the integration of sensorimotor processes (Baker, 2007) through large-scale communication (Roelfsema et al., 1997; Brovelli et al., 2004; Tsujimoto et al., 2009). Reversely, the contrast between the brain activity of the induced imitator versus NVM revealed modulations in alpha-mu and delta/theta-frequency bands over fronto-central and parietal regions like for action observation but not in beta, unlike in action production. This focal increase in delta activity might be associated with an attentional control over the primary motor cortex. Although delta frequency band is poorly documented concerning motor-related tasks, recent studies suggest indeed that delta activity may reflect a potential top-down control in perceptive tasks (Lakatos et al., 2008; Anastassiou et al., 2011). We reasoned that the decrease in beta activity should, therefore, be related to a primacy of action in self, and the increase in delta/theta activity to a primacy of observation of the model in other, therefore, underlining other-ascription of action primacy.

Shared agency during spontaneous imitation condition

We compared each role in the SI condition with the NVM baseline. Unlike in II, oscillatory rhythms were similar for model and imitator (see Figure 5). For both roles, contrasts showed a gamma increase over parietal regions. Gamma frequency has been associated with various cognitive functions (Jensen et al., 2007) and was reported to reflect local processing at the cortical level (Fries, 2009). Importantly, an increase in gamma activity has been found over parietal region during the perception and ascription of biological movement (Pavlova et al., 2006), and TPJ region has been shown to play critical functions in attention, agency and social interaction (Decety and Lamm, 2007). The gamma increase was not found in other contrasts than those involving the two spontaneous roles of imitation. This symmetric increase is proposed here as related to the phenomenon of shared agency between the two interacting partners. Particularly relevant with this proposal is the study by Kanayama et al. (2009) showing a gamma increase related to intermodal interaction when the rubber hand is attributed to self.

Finally, comparing each role according to the condition led us to observe a theta decrease for the imitator in SI compared to II. Theta-frequency activity has been reported to be involved in working memory (Scheeringa et al., 2009; Brookes et al., 2011) and thus its recruitment can point out a cognitive load during instructed imitation.

Beyond symmetry

The stance highlighting the intra-brain symmetry between observation and action has gained a renewed influence after the discovery of the MNS (Rizzolatti and Craighero, 2004; Caetano et al., 2007) and rapidly extended to hypotheses concerning inter-brain symmetry. In favor of this extension are the biological similarities and constraints among conspecifics (Hasson et al., 2004). More precisely, the anatomic-functional similarity among human brains enhances dynamical similarities and thus facilitates interindividual couplings (Dumas et al., 2012). However, the neuromimetic model cannot fully account for social interaction (Petit, 2003). Beyond symmetry indeed, another component of any social interaction is in play: namely, alternation in complementary social roles, yielding asymmetry of action processing in the interacting partners. This component is especially important to assess a multiaccount of agency. While the symmetry of action generates shared feeling of agency, the asymmetry of roles leads to alternate the ascription of who is the agent of what. At some extent, we can consider the condition of II as an amplifier of the asymmetry of roles inasmuch as the normal flow of interaction is disrupted by the instruction to maintain the role. In this condition therefore, there is a difference between model and imitator that can be understood as a clear-cut difference in ascription of action primacy. Reversely, the condition of SI certainly acts as an amplifier of symmetry since partners share perception and action and anticipate next exchange of role, thus generating a binding between people (Hari and Kujala, 2009). Everyday social interaction is certainly at the middle of the road. In the same way as segregation and integration form a complementary pair in brain activity, a successful communication needs altogether a clear repartition of the roles and a co-regulation of the exchange (Fogel, 1993). This co-regulation and the sharing of purpose between the interactants ensure the autonomy of the two partners as well as their ability to make the distinction between what originates from self and what originates from the other.

Methodological issues

Convergent evidence in neuroscience leads to underline that cortical mechanisms are not fully described by a simple functional specificity of spatial regions or electrophysiological rhythms (Roopun et al., 2008; Kopell et al., 2010). However, temptation remains high, in the realm of social neuroscience, to search for a specific signature of social interaction. The alpha-mu rhythm illustrates well this complex issue. Following the demonstration of its dissociative functions in the processing of sensorimotor information for different frequency ranges and somatotopic regions (Pfurtscheller et al., 2000), it has been recently suggested that rhythms in this frequency range could have more specific social meaning in other regions than in sensorimotor cortices (Naeem et al., 2011) albeit mu rhythm modulation is currently the main EEG signature proposed for MNS (Pineda, 2005; Oberman et al., 2008). At least if the focus remains a search for specific signature of social cognition, detailed spectral analyzes should be used following Tognoli and colleagues (Tognoli et al., 2007) when they identified phi markers. Connectivity approaches also represent a promising methodological jump for the future. If we take as an example the fronto-parietal network, it has been proposed by Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia (Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia, 2010) to be at the core of social cognition. Neural oscillations within this network have been closely associated with cognitive processes during the course of social interactions such as sensorimotor integration (Basar et al., 2001; Palva and Palva, 2007), perception-action coupling (Hari et al., 1998; Pineda, 2005; Calmels et al., 2008) or control of spatial attention (Capotosto et al., 2009). However, strong functional links have also been found to play a key role in perceptual awareness without any social context (Gaillard et al., 2009). An integrative vista is thus specifically needed in the case of social cognition where multiple cognitive functions are jointly at play. The present study adopted such a perspective and considered the potential diversity of brain dynamics underlying agency. Although the present results only give a partial account of this diversity, they nevertheless point on dissociation at the neural level between self-, other-, and shared-ascription of action primacy. Moreover, the difference observed between spontaneous and II illustrates the crucial importance of the context in the investigation of brain correlates of social interaction. Systemic and dynamical approaches in social neuroscience may help disentangling multiple types of neural correlates and bring them together into a coherent whole.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Florence Bouchet for her generous assistance in the EEG preparation, Pierre Canet and Laurent Hugueville for their technical assistance, and Mario Chavez for helpful comments in EEG analysis. The work of Guillaume Dumas was supported by a PhD grant of the DGA.

Appendix

Table A1.

Summary of amplitude for delta, theta, alpha-mu, beta, and gamma frequency bands.

| Delta | Theta | Alpha-Mu | Beta | Gamma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal | NVM-NVNM (+) | NVM-NVNM (−) | |||

| LIHM-NVNM (+) | Mod(II)-NVM (−) | ||||

| Im(II)-NVM (+) | |||||

| Central | NVM-NVNM (+) | LIHM-NVNM (+) | NVM-NVNM (−) | NVM-NVNM (−) | Im(SI)-NVM (+) |

| LIHM-NVNM (+) | Mod(II)-NVM (+) | LIHM-NVNM (−) | Mod(II)-NVM (−) | Mod(SI)-NVM (+) | |

| Im(II)-NVM (+) | Im(SI)-Im(II) (−) | Im(II)-NVM (−) | |||

| Mod(II)-NVM (−) | |||||

| Parietal | LIHM-NVNM (+) | LIHM-NVNM (+) | NVM-NVNM (−) | ||

| Mod(II)-NVM (+) | LIHM-NVNM (−) | ||||

| Im(SI)-Im(II) (−) | Im(II)-NVM (−) | Im(SI)-NVM (+) | |||

| Im(SI)-NVM (−) | Mod(SI)-NVM (+) | ||||

| Mod(II)-NVM (−) | |||||

| Mod(SI)-NVM (−) | |||||

| Im(SI)-Im(II) (−) | |||||

| Occipital | Im(SI)-Im(II) (−) | Im(SI)-Im(II) (−) | Im(SI)-NVM (+) | ||

| Im(SI)-NVM (−) | Mod(SI)-NVM (+) | ||||

| Mod(SI)-NVM (−) |

(+) indicates an increase and (−) a decrease of EEG amplitudes. NVNM, no view no motion; NVM, no view motion; LIHM, library of intransitive hand movements; Im, imitator; Mod, model; SI, spontaneous imitation; II, induced imitation.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/Human_Neuroscience/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00128/abstract

Video S1 | Video extract of a spontaneous imitation trial.

References

- Anastassiou C. A., Perin R., Markram H., Koch C. (2011). Ephaptic coupling of cortical neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 217–223 10.1038/nn.2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton-James C., van Baaren R. B., Chartrand T. L., Decety J., Karremans J. (2007). Mimicry and me: the impact of mimicry on self-construal. Soc. Cogn. 25, 518–535 [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi L., Toppi J., Fallani F. D., Vecchiato G., Salinari S., Mattia D., Cincotti F., Babiloni F. (2010). Neuroelectrical hyperscanning measures simultaneous brain activity in humans. Brain Topogr. 23, 243–256 10.1007/s10548-010-0147-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiloni F., Cincotti F., Mattia D., Mattiocco M., Fabrizio D. V. F. D., Tocci A., Bianchi L., Marciani M. G., Astolfi L. (2006). “Hypermethods for EEG hyperscanning. 2006. EMBS 06,” in 28th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, (New York, NY, USA: ), 3666–3669 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. N. (2007). Oscillatory interactions between sensorimotor cortex and the periphery. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 649–655 10.1016/j.conb.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basar E., Basar-Eroglu C., Karakas S., Schurmann M. (2001). Gamma, alpha, delta, and theta oscillations govern cognitive processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 39, 241–248 10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00145-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M., Cohen J. (1998). Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 391, 756 10.1038/35784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes M. J., Wood J. R., Stevenson C. M., Zumer J. M., White T. P., Liddle P. F., Morris P. G. (2011). Changes in brain network activity during working memory tasks: a magnetoencephalography study. Neuroimage 55, 1804–1815 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brovelli A., Ding M., Ledberg A., Chen Y., Nakamura R., Bressler S. L. (2004). Beta oscillations in a large-scale sensorimotor cortical network: directional influences revealed by Granger causality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9849–9854 10.1073/pnas.0308538101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundick T., Spinella M. (2000). Subjective experience, involuntary movement, and posterior alien hand syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 68, 83–85 10.1136/jnnp.68.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G., Draguhn A. (2004). Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science 304, 1926–1929 10.1126/science.1099745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano G., Jousmaki V., Hari R. (2007). Actor's and observer's primary motor cortices stabilize similarly after seen or heard motor actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9058–9062 10.1073/pnas.0702453104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmels C., Hars M., Holmes P., Jarry G., Stam C. J. (2008). Non-linear EEG synchronization during observation and execution of simple and complex sequential finger movements. Exp. Brain Res. 190, 389–400 10.1007/s00221-008-1480-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capotosto P., Babiloni C., Romani G. L., Corbetta M. (2009). Frontoparietal cortex controls spatial attention through modulation of anticipatory alpha rhythms. J. Neurosci. 29, 5863–5872 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0539-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochin S., Barthelemy C., Roux S., Martineau J. (1999). Observation and execution of movement: similarities demonstrated by quantified electroencephalography. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 1839–1842 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daprati E., Sirigu A., Pradat-Diehl P., Franck N., Jeannerod M. (2000). Recognition of self-produced movement in a case of severe neglect. Neurocase 6, 477–486 [Google Scholar]

- David N., Newen A., Vogeley K. (2008). The “sense of agency” and its underlying cognitive and neural mechanisms. Conscious. Cogn. 17, 523–534 10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jaegher H., Froese T. (2009). On the role of social interaction in individual agency. Adapt. Behav. 17, 444–460 [Google Scholar]

- de Vignemont F. (2011). Embodiment, ownership and disownership. Conscious. Cogn. 20, 82–93 10.1016/j.concog.2010.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vignemont F., Fourneret P. (2004). The sense of agency: a philosophical and empirical review of the “Who” system. Conscious. Cogn. 13, 1–19 10.1016/S1053-8100(03)00022-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J., Lamm C. (2007). The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: how low-level computational processes contribute to meta-cognition. Neuroscientist 13, 580–593 10.1177/1073858407304654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas G., Chavez M., Nadel J., Martinerie J. (2012). Anatomical connectivity influences both intra- and inter-brain synchronizations. PLoS ONE 7:e36414 10.1371/journal.pone.0036414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas G., Nadel J., Soussignan R., Martinerie J., Garnero L. (2010). Inter-brain synchronization during social interaction. Plos One 5:e12166 10.1371/journal.pone.0012166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrsson H. H., Holmes N. P., Passingham R. E. (2005). Touching a rubber hand: feeling of body ownership is associated with activity in multisensory brain areas. J. Neurosci. 25, 10564–10573 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer C., Franck N., Georgieff N., Frith C. D., Decety J., Jeannerod A. (2003). Modulating the experience of agency: a positron emission tomography study. Neuroimage 18, 324–333 10.1016/S1053-8119(02)00041-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer C., Frith C. D. (2002). Experiencing oneself vs another person as being the cause of an action: the neural correlates of the experience of agency. Neuroimage 15, 596–603 10.1006/nimg.2001.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink G. R., Marshall J. C., Halligan P. W., Frith C. D., Driver J., Frackowiak R. S. J., Dolan R. J. (1999). The neural consequences of conflict between intention and the senses. Brain 122, 497–512 10.1093/brain/122.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. (1993). “Two principles of communication: Co-regulation and framing,” in New Perspectives in Early Communicative Development, eds Nadel J., Camaioni L. (London: Routledge; ), 9–22 [Google Scholar]

- Fries P. (2009). Neuronal gamma-band synchronization as a fundamental process in cortical computation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 209–224 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C. D., Blakemore S. J., Wolpert D. M. (2000). Explaining the symptoms of schizophrenia: abnormalities in the awareness of action. Brain Res. Rev. 31, 357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard R., Dehaene S., Adam C., Clemenceau S., Hasboun D., Baulac M., Cohen L., Naccache L. (2009). Converging intracranial markers of conscious access. PLoS Biol. 7:e61 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. (2000). Philosophical conceptions of the self: implications for cognitive science. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. (2007). The natural philosophy of agency. Philos. Compass 2, 347–357 [Google Scholar]

- Grynszpan O. (2006). Modified version of ELAN software. [Online]. Available: http://www.lat-mpi.eu/tools/elan [Google Scholar]

- Guionnet S., Nadel J., Bertasi E., Sperduti M., Delaveau P., Fossati P. (2011). Reciprocal imitation: toward a neural basis of social interaction. Cereb. Cortex 22, 971–978 10.1093/cercor/bhr177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari R., Forss N., Avikainen S., Kirveskari E., Salenius S., Rizzolatti G. (1998). Activation of human primary motor cortex during action observation: a neuromagnetic study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15061–15065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari R., Kujala M. V. (2009). Brain basis of human social interaction: from concepts to brain imaging. Physiol. Rev. 89, 453–479 10.1152/physrev.00041.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson U., Nir Y., Levy I., Fuhrmann G., Malach R. (2004). Intersubject synchronization of cortical activity during natural vision. Science 303, 1634–1640 10.1126/science.1089506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. (2003a). “Consciousness of action and self-consciousness: a cognitive neuroscience approach,” in Agency and Self-Awareness. Issues in Philosophy and Psychology, ed Eilan J. R. N. (Oxford: Oxford University Press; ), 142 [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. (2003b). The mechanism of self-recognition in humans. Behav. Brain Res. 142, 1–15 10.1016/S0166-4328(02)00384-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O., Kaiser J., Lachaux J. P. (2007). Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends Neurosci. 30, 317–324 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama N., Sato A., Ohira H. (2009). The role of gamma band oscillations and synchrony on rubber hand illusion and crossmodal integration. Brain Cogn. 69, 19–29 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopell N., Kramer M. A., Malerba P., Whittington M. A. (2010). Are different rhythms good for different functions? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4:187 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos P., Karmos G., Mehta A. D., Ulbert I., Schroeder C. E. (2008). Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science 320, 110–113 10.1126/science.1154735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage J. F., Theoret H. (2006). EEG evidence for the presence of an action observation-execution matching system in children. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2505–2510 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U., Li S. C., Gruber W., Muller V. (2009). Brains swinging in concert: cortical phase synchronization while playing guitar. BMC Neurosci. 10, 22 10.1186/1471-2202-10-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R. R. (1988). The intrinsic electrophysiological properties of mammalian neurons: insights into central nervous system function. Science 242, 1654–1664 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganotti P., Gerloff C., Toro C., Katsuta H., Sadato N., Zhuang P., Leocani L., Hallett M. (1998). Task-related coherence and task-related spectral power changes during sequential finger movements. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 109, 50–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcel A. (2003). “The sense of agency: Awareness and ownership of action,” in Agency and Self-Awareness: Issues in Philosophy and Psychology, eds Roessler J., Eilan N. (Oxford: Claradon Press; ), 48–93 [Google Scholar]

- Maris E., Oostenveld R. (2007). Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods 164, 177–190 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E., Schoffelen J. M., Fries P. (2007). Nonparametric statistical testing of coherence differences. J. Neurosci. Methods 163, 161–175 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff A. N. (1990). Foundations for Developing a Concept of Self: The Role of Imitation in Relating Self to Other and the Value of Social Mirroring, Social Modeling and Self Practice in Infancy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Montague P. R., Berns G. S., Cohen J. D., Mcclure S. M., Pagnoni G., Dhamala M., Wiest M. C., Karpov I., King R. D., Apple N., Fisher R. E. (2002). Hyperscanning: simultaneous fMRI during linked social interactions. Neuroimage 16, 1159–1164 10.1006/nimg.2002.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. W., Ruge D., Wenke D., Rothwell J., Haggard P. (2010). Disrupting the experience of control in the human brain: pre-supplementary motor area contributes to the sense of agency. Proc. Biol. Sci. 277, 2503–2509 10.1098/rspb.2010.0404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaraswamy S. D., Singh K. D. (2008). Modulation of the human mirror neuron system during cognitive activity. Psychophysiology 45, 896–905 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J. (2006). “Does imitation matter to children with autism?,” in Imitation and the Development of the Social Mind: Lessons from Typical Development and Autism, ed Williams S. R. J. (New York, NY: Guilford Publications; ), 118–137 [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J., Baudonnière P. (1982). The social function of reciprocal imitation in 2-y-o peers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 5, 89–105 [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J., Butterworth G. (1999). Imitation in Infancy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J., Carchon I., Kervella C., Marcelli D., Réserbat-Plantey D. (1999). Expectancies for social contingency in 2-month-olds. Dev. Sci. 2, 164–173 [Google Scholar]

- Nadel J., Croué S., Mattlinger M. J., Cqanet P., Hudelot C., Lécuyer C., Martini M. (2000). Do autistic children have expectancies about the social behaviour of unfamiliar people? Autism 2, 133–145 [Google Scholar]

- Naeem M., Prasad G., Watson D. R., Kelso J. (2011). Electrophysiological signatures of intentional social coordination in the 10-12 Hz range. Neuroimage 59, 1795–1803 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahab F. B., Kundu P., Gallea C., Kakareka J., Pursley R., Pohida T., Miletta N., Friedman J., Hallett M. (2011). The neural processes underlying self-agency. Cereb. Cortex 21, 48–55 10.1093/cercor/bhq059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols T. E., Holmes A. P. (2002). Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: a primer with examples. Hum. Brain Mapp. 15, 1–25 10.1002/hbm.1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberman L. M., Mccleery J. P., Ramachandran V. S., Pineda J. A. (2007). EEG evidence for mirror neuron activity during the observation of human and robot actions: toward an analysis of the human qualities of interactive robots. Neurocomputing 70, 2194–2203 [Google Scholar]

- Oberman L. M., Ramachandran V. S., Pineda J. A. (2008). Modulation of mu suppression in children with autism spectrum disorders in response to familiar or unfamiliar stimuli: the mirror neuron hypothesis. Neuropsychologia 46, 1558–1565 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palva S., Palva J. M. (2007). New vistas for alpha-frequency band oscillations. Trends Neurosci. 30, 150–158 10.1016/j.tins.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D., Nichols T. E., Baillet S., Leahy R. M. (2005). A comparison of random field theory and permutation methods for the statistical analysis of MEG data. Neuroimage 25, 383–394 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova M., Birbaumer N., Sokolov A. (2006). Attentional modulation of cortical neuromagnetic gamma response to biological movement. Cereb. Cortex 16, 321–327 10.1093/cercor/bhi108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova M., Guerreschi M., Lutzenberger W., Krageloh-Mann I. (2010). Social interaction revealed by motion: dynamics of neuromagnetic gamma activity. Cereb. Cortex 20, 2361–2367 10.1093/cercor/bhp304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit J. L. (2003). On the relation between recent neurobiological data on perception (and action) and the Husserlian theory of constitution. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2, 281–298 [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller G., Neuper C., Krausz G. (2000). Functional dissociation of lower and-upper frequency mu rhythms in relation to voluntary limb movement. Clin. Neurophysiol. 111, 1873–1879 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00428-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda J. A. (2005). The functional significance of mu rhythms: translating “seeing” and “hearing” into “doing”. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 50, 57–68 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G., Craighero L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 169–192 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G., Sinigaglia C. (2010). The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: interpretations and misinterpretations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 264–274 10.1038/nrn2805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema P. R., Engel A. K., Konig P., Singer W. (1997). Visuomotor integration is associated with zero time-lag synchronization among cortical areas. Nature 385, 157–161 10.1038/385157a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopun A. K., Kramer M. A., Carracedo L. M., Kaiser M., Davies C. H., Traub R. D., Kopell N. J., Whittington M. A. (2008). Temporal interactions between cortical rhythms. Front. Neurosci. 2:145–154 10.3389/neuro.01.034.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby P., Decety J. (2001). Effect of subjective perspective taking during simulation of action: a PET investigation of agency. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 546–550 10.1038/87510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby P., Decety J. (2003). What you believe versus what you think they believe: a neuroimaging study of conceptual perspective-taking. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17, 2475–2480 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa R., Petersson K. M., Oostenveld R., Norris D. G., Hagoort P., Bastiaansen M. C. (2009). Trial-by-trial coupling between EEG and BOLD identifies networks related to alpha and theta EEG power increases during working memory maintenance. Neuroimage 44, 1224–1238 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloetjes H., Wittenburg P. (2008). “Annotation by category: elan and iso dcr,” Proceedings of the Sixth International Language Resources and Evaluation (LRECí08), Marrakech, Morocco, May. [Google Scholar]

- Soussignan R., Nadel J., Canet P., Gerardin P. (2006). Sensitivity to social contingency and positive emotion in 2-month-olds. Infancy 10, 123–144 [Google Scholar]

- Spengler S., Von Cramon D. Y., Brass M. (2009). Was it me or was it you? How the sense of agency originates from ideomotor learning revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage 46, 290–298 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperduti M., Delaveau P., Fossati P., Nadel J. (2011). Different brain structures related to self- and external-agency attribution: a brief review and meta-analysis. Brain Struct. Funct. 216, 151–157 10.1007/s00429-010-0298-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. (2006). Grouping of brain rhythms in corticothalamic systems. Neuroscience 137, 1087–1106 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik M., Vosgerau G., Newen A. (2008). Beyond the comparator model: a multifactorial two-step account of agency. Conscious. Cogn. 17, 219–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirioux B., Mercier M. R., Jorland G., Berthoz A., Blanke O. (2010). Mental imagery of self-location during spontaneous and active self-other interactions: an electrical neuroimaging study. J. Neurosci. 30, 7202–7214 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3403-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognoli E., Lagarde J., Deguzman G. C., Kelso J. A. S. (2007). The phi complex as a neuromarker of human social coordination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8190–8195 10.1073/pnas.0611453104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiris M., Haggard P. (2005). Experimenting with the acting self. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 22, 387–407 10.1080/02643290442000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiris M., Longo M. R., Haggard P. (2010). Having a body versus moving your body: neural signatures of agency and body-ownership. Neuropsychologia 48, 2740–2749 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto T., Mima T., Shimazu H., Isomura Y. (2009). Directional organization of sensorimotor oscillatory activity related to the electromyogram in the monkey. Clin. Neurophysiol. 120, 1168–1173 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.02.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallstrom G. L., Kass R. E., Miller A., Cohn J. F., Fox N. A. (2004a). Automatic correction of ocular artifacts in the EEG: a comparison of regression-based and component-based methods. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 53, 105–119 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallstrom G. L., Kass R. E., Miller A., Cohn J. F., Fox N. A. (2004b). Automatic correction of ocular artifacts in the EEG: a comparison of regression-based and component-based methods. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 53, 105–119 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein L. (1958). Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell; 10.1007/s10936-010-9153-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yomogida Y., Sugiura M., Sassa Y., Wakusawa K., Sekiguchi A., Fukushima A., Takeuchi H., Horie K., Sato S., Kawashima R. (2010). The neural basis of agency: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 50, 198–207 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]