Abstract

Ventral rectopexy has gained popularity in Europe to treat full-thickness rectal external and internal prolapse. This procedure has been shown to achieve acceptable anatomic results with low recurrence rates, few complications, and improvements of both constipation and fecal incontinence. The authors review the principles, techniques, and outcomes of ventral rectopexy.

Keywords: anterior ventral rectopexy, rectal prolapse

Objectives: On completion of this article, the reader should be able to describe the technique and benefit of anterior ventral rectopexy.

Ventral rectopexy (VR) has gained momentum in recent years as an operation for both full-thickness and internal rectal prolapse. Dissection is performed anterior to the rectum and mesh is fixed to the rectal wall and suspended to the sacrum. The initial description of VR known as the Orr-Loygue procedure involves full rectal mobilization anteriorly and posteriorly to the levator ani muscle level and suturing two meshes on to the anterolateral rectal wall.1 D’Hoore described a modified VR performed laparoscopically.2 Only the Denonvilliers fascia is dissected to expose anterior rectal wall and a single mesh is sutured onto the anterior aspect of the distal rectum. Posterior dissection is avoided and limited only to clearing the sacral promontory sufficiently for mesh fixation. Proponents of ventral rectopexy report low recurrence rates and functional improvements for both fecal incontinence and constipation.3,4,5 The aim of this review is to describe surgical technique and associated outcomes of VR.

Prevalence

Although internal and external rectal prolapse are not life-threatening conditions, these disorders can be extremely debilitating and have a negative impact on quality of life. Effected individuals may report discomfort or pain from prolapsing tissue, drainage of mucus or blood, and associated fecal incontinence or difficult evacuation. Women aged 50 and older are 6 times as likely as men to present with rectal prolapse.6,7 Two thirds of women are multiparous and 15 to 30% report associated urinary dysfunction and vaginal prolapse.8

Pathophysiology of Posterior Compartment Prolapse

The pelvic floor is often considered in terms of three compartments: anterior, middle, and posterior. Posterior compartment disorders include rectal prolapse (RP), which involves full-thickness descent of the rectum through the anal muscles or rectal intussusception (RI). RI is the funnel-shaped infolding of the rectal wall that occurs during defecation. The cause of RP is unknown but the risk of developing RP may be increased by having defects of the anterior pelvic floor or supporting structures,9or RI associated with straining.10 Associated findings include diastasis of the levator ani, an abnormally deep cul-de-sac, a redundant sigmoid colon, a patulous anus, and loss of rectal sacral attachments. The clinical significance of RI is controversial. Normal volunteers have demonstrated occult rectal prolapse as high as 20%, suggesting some internal prolapse may be within normal physiologic variability.11 Observational studies show that the progression of RI to external prolapse is uncommon12,13 and that posterior rectopexy does not correct obstructed defecation associated with RI.14 Other authors suggest that RI represents the first stage of a progressive disorder that leads to external prolapse.15 VR has been suggested as a procedure that benefits patients with RI with or without RP by correcting the leading cause (the RIs), preserving rectal innervation, and lifting the middle compartment, thus correcting coexisting enterocele or vaginal descent.16

Patient Evaluation and Testing

Prior to operative intervention, a detailed patient-focused history and physical examination should be performed. If the diagnosis of RI or RP is suspected from the history but not detected on examination, then confirmation can be obtained by examining the patient while straining on the commode or by having the patient photograph the prolapse at home. Full examination of the perineum and complete anorectal examination may demonstrate a patulous anus and diminished sphincter tone. Colonic lesions and colitis should be excluded by colonoscopic examination. Defecography may be recommended to reveal RI, rectocele, enterocele, and sigmoidocele. For those patients with symptoms of vaginal prolapse or urinary incontinence, a urogynecologic examination and urodynamics should be considered. Surgical intervention may be needed for anterior, middle, and posterior compartments.17 Anorectal physiologic studies can be performed selectively. Testing rarely changes the operative strategy, but can often guide treatment for associated functional abnormalities.18

Operative Technique

Prophylactic antibiotics and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis are given in accordance with the Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP) measures.19 Full mechanical bowel preparation is not necessary and rectal washout is performed under anesthesia to empty the lower rectum. The patient is placed in a modified lithotomy position in yellow-fin stirrups with careful padding of the lower extremities. Both arms are tucked and the patient is secured to the table at the level of the chest with foam padding and tape or a beanbag for stabilization.

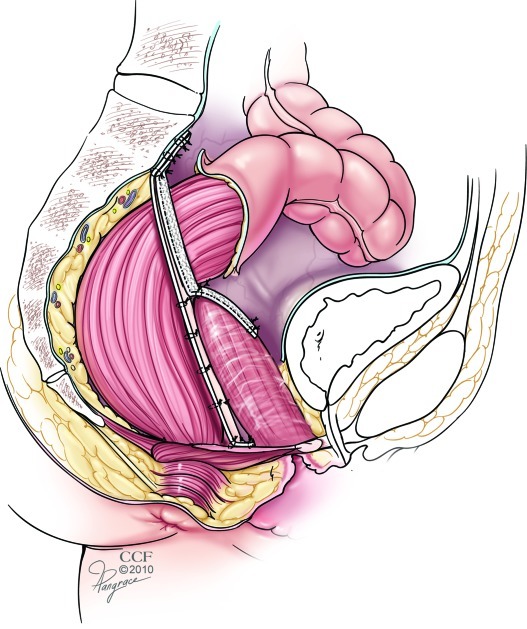

Using a 4-port technique, the camera is placed at the umbilicus and 5-mm trocars are inserted in the left and right lower quadrants at the midaxillary lines. A 12-mm trocar is placed in the suprapubic region just to the right of midline. Steep Trendelenburg positioning is used to expose the pelvic organs, and the small bowel is retracted cephalad. Hysteropexy may be performed as needed for exposure. The rectosigmoid is retracted toward the spleen to expose the peritoneum. The right ureter is identified along the right pelvic sidewall. The right-side peritoneum is then incised at the level of the sacral promontory and the peritoneal dissection continues downward in the midpoint between the rectum and sidewall to the level of the pelvic floor. Using dilators in the vagina and rectum, the rectovaginal septum is splayed open and the peritoneum over the pouch of Douglas is excised to expose the anterior rectum. If a symptomatic rectocele or perineal descent is present, the dissection can be carried down to the perineal body and pubococcygeus muscles for additional support. Polypropylene or biologic mesh measuring ∼7 × 15 cm is introduced though the 12-mm trocar site. We use 2–0 polydiaxone suture to secure the mesh to the pelvic floor muscle laterally and the anterior rectal wall using six to eight laparoscopic sutures. Care should be taken to avoid full-thickness rectal bites. The sacral lateral anterior ligament is exposed at the sacral promontory and two laparoscopic sutures or tacks can be used to secure the mesh to the sacrum. The rectum should not be placed under tension. The peritoneum is closed over the mesh. Additional procedures for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence may also be performed in conjunction with VR (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ventral rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy. Mesh is fixed to the anterior rectum and anterior vagina and suspended to the sacrum for combined repair of both rectal and vaginal prolapse. Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2010–2011. All Rights Reserved.

Outcomes

Samaranayake and colleagues performed a systematic review of VR and identified 12 nonrandomized case series with a total of 728 patients.20 Seven studies used the Orr- Loygue procedure and five studies used the D’Hoore VR. Recurrence rates for RP across all studies was estimated at 3.4% (95% CI, 2.0%–4.8%). Complication rates varied from 14 to 47% and urinary tract infection (n = 11) and incisional hernia (n = 16) were most common. All of the studies used synthetic polypropylene mesh and related complications included mesh infection leading to sepsis (n = 1), vaginal mesh erosion (n = 1), and mesh detachment (n = 2). The concern over implantable synthetic materials has led our facility to try alternative biologic meshes in place of synthetics. Intervertebral disk infection, a rare complication after abdominal sacrocolpopexy or rectopexy, was reported in two patients.21,22,23 We have seen this complication in our unpublished series; therefore, we advocate early imaging for patients who complain of back pain after VR. The overall mean decrease in postoperative constipation rate over all studies was estimated at 23.9% (95% CI, 6.8%–40.9%). New-onset constipation after surgery was observed in seven studies with a mean rate of 14.4% (95% CI, 6.4%–22.3%).

Studies that used VR without posterior rectal mobilization reported a greater reduction in postoperative constipation and lower rates of new-onset constipation compared with patients with posterior rectal mobilization. The overall mean decrease in FI rate after VR was 44.9% (95% CI, 35.6%–54.1%)20 These studies are limited as a result of the lack of randomization or comparison to other techniques, heterogeneity in patient selection and follow-up and variability on definitions and outcome measurements.

Robotic VR

Ventral rectopexy may be completed with the assistance of a robotic surgical system that can reduce some of the technical challenges of traditional laparoscopy.24 The da Vinci Surgical System® (Intuitive Surgical, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) increases the degrees of freedom over conventional laparoscopy and makes suturing easier. Robotic procedures are associated with an increased cost and operative time compared with laparoscopy.25

Conclusion

Ventral rectopexy has emerged as a viable surgical option for rectal prolapse and RI in European centers. American surgeons have been late adopters, but there is a growing interest in this procedure. Randomized control trials will be required to determine the best operation for patients with posterior compartment prolapse.

References

- 1.Loygue J, Nordlinger B, Cunci O, Malafosse M, Huguet C, Parc R. Rectopexy to the promontory for the treatment of rectal prolapse. Report of 257 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27(6):356–359. doi: 10.1007/BF02552998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Hoore A, Cadoni R, Penninckx F. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for total rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 2004;91(11):1500–1505. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Hoore A, Penninckx F. Laparoscopic ventral recto(colpo)pexy for rectal prolapse: surgical technique and outcome for 109 patients. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(12):1919–1923. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0485-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boons P, Collinson R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for external rectal prolapse improves constipation and avoids de novo constipation. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(6):526–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collinson R, Wijffels N, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for internal rectal prolapse: short-term functional results. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(2):97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madiba T E, Baig M K, Wexner S D. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Arch Surg. 2005;140(1):63–73. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kairaluoma M V, Kellokumpu I H. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg. 2005;94(3):207–210. doi: 10.1177/145749690509400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Argenté F X, Jain A, Nogueras J J, Davila G W, Weiss E G, Wexner S D. Prevalence and severity of urinary incontinence and pelvic genital prolapse in females with anal incontinence or rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(7):920–926. doi: 10.1007/BF02235476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ripstein C B, Lanter B. Etiology and surgical therapy of massive prolapse of the rectum. Ann Surg. 1963;157:259–264. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196302000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodén B, Snellman B. Procidentia of the rectum studied with cineradiography. A contribution to the discussion of causative mechanism. Dis Colon Rectum. 1968;11(5):330–347. doi: 10.1007/BF02616986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shorvon P J, McHugh S, Diamant N E, Somers S, Stevenson G W. Defecography in normal volunteers: results and implications. Gut. 1989;30(12):1737–1749. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.12.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellgren A, Schultz I, Johansson C, Dolk A. Internal rectal intussusception seldom develops into total rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(7):817–820. doi: 10.1007/BF02055439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi J S, Hwang Y H, Salum M R. et al. Outcome and management of patients with large rectoanal intussusception. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(3):740–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orrom W J, Bartolo D C, Miller R, Mortensen N J, Roe A M. Rectopexy is an ineffective treatment for obstructed defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(1):41–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijffels N Cunningham C Lindsey I Laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for obstructed defecation syndrome Surg Endosc 2009232452, author reply 453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones O M, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. The assessment and management of rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception, rectocoele, and enterocoele in adults. BMJ. 2011;342:c7099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagar P M, Thekkinkattil D K, Heath R M, Woodfield J, Gonsalves S, Landon C R. Feasibility and functional outcome of laparoscopic sacrocolporectopexy for combined vaginal and rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(9):1414–1420. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varma M Rafferty J Buie W D; Standards Practice Task Force of American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for the management of rectal prolapse Dis Colon Rectum 201154111339–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellinger E P. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures: the whole is greater than the parts. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(12):1781–1785. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samaranayake C B, Luo C, Plank A W, Merrie A E, Plank L D, Bissett I P. Systematic review on ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse and intussusception. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(6):504–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draaisma W A, Eijck M M van, Vos J, Consten E C. Lumbar discitis after laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(2):255–256. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0971-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajamaheswari N Agarwal S Seethalakshmi K. Lumbosacral spondylodiscitis: an unusual complication of abdominal sacrocolpopexy Int Urogynecol J 2011. September 2 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salman M M, Hancock A L, Hussein A A, Hartwell R. Lumbosacral spondylodiscitis: an unreported complication of sacrocolpopexy using mesh. BJOG. 2003;110(5):537–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong M T, Meurette G, Rigaud J, Regenet N, Lehur P A. Robotic versus laparoscopic rectopexy for complex rectocele: a prospective comparison of short-term outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(3):342–346. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f4737e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heemskerk J, de Hoog D E, Gemert W G van, Baeten C G, Greve J W, Bouvy N D. Robot-assisted vs. conventional laparoscopic rectopexy for rectal prolapse: a comparative study on costs and time. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1825–1830. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]