Abstract

Lateral abdominal wall (LAW) defects can manifest as a flank hernias, myofascial laxity/bulges, or full-thickness defects. These defects are quite different from those in the anterior abdominal wall defects and the complexity and limited surgical options make repairing the LAW a challenge for the reconstructive surgeon. LAW reconstruction requires an understanding of the anatomy, physiologic forces, and the impact of deinnervation injury to design and perform successful reconstructions of hernia, bulge, and full-thickness defects. Reconstructive strategies must be tailored to address the inguinal ligament, retroperitoneum, chest wall, and diaphragm. Operative technique must focus on stabilization of the LAW to nonyielding points of fixation at the anatomic borders of the LAW far beyond the musculofascial borders of the defect itself. Thus, hernias, bulges, and full-thickness defects are approached in a similar fashion. Mesh reinforcement is uniformly required in lateral abdominal wall reconstruction. Inlay mesh placement with overlying myofascial coverage is preferred as a first-line option as is the case in anterior abdominal wall reconstruction. However, interposition bridging repairs are often performed as the surrounding myofascial tissue precludes a dual layered closure. The decision to place bioprosthetic or prosthetic mesh depends on surgeon preference, patient comorbidities, and clinical factors of the repair. Regardless of mesh type, the overlying soft tissue must provide stable cutaneous coverage and obliteration of dead space. In cases where the fasciocutaneous flaps surrounding the defect are inadequate for closure, regional pedicled flaps or free flaps are recruited to achieve stable soft tissue coverage.

Keywords: lateral abdominal wall reconstruction, hernia, bulge, biologic mesh, bioprosthetic mesh, component separation

The focus of abdominal wall reconstruction (AWR) has been on the central abdomen due to the more commonly encountered ventral hernia and parastomal hernia defects. As a result, the core surgical strategies that have been the mainstay of AWR have been designed and refined based on the musculofascial anatomy and physiologic dynamics of the central anterior abdominal wall. Beyond the central abdomen, lies the lateral abdominal wall (LAW), which represents unique challenges in abdominal wall reconstruction. The LAW encompasses the region from the linea semilunaris to the paraspinal muscles posteriorly and from the costal margin to the inguinal canal/iliac crest beyond the central abdominal wall, which is defined laterally by the linea semilunaris, superiorly by the medial costal cartilage and inferiorly by the pubic bone and medial inguinal ligament. The myofascial anatomy of the LAW is comprised of the external oblique muscle, internal oblique muscle, transverse abdominis muscle, and transversalis fascia with their associated obliquely oriented neurovascular bundles. These muscle layers have relatively little aponeurotic substance laterally and when injured or deinnervated are more difficult to repair than defects in the anterior abdominal wall.

LAW defects can manifest as a flank hernia, myofascial laxity, or bulge; their complexity and limited surgical solutions make repairing the LAW a challenge for the reconstructive surgeon. Although less common than central defects, the LAW represents a far greater surface area for potential hernia and/or bulge development. LAW hernias are generally broad based and less commonly obstructive compared with ventral hernias; however, LAW hernias are typically rapidly progressive. In addition, these defects are by definition asymmetrically located within the abdominal wall. Thus, the distraction forces on the defect create inherent imbalanced strain on the anterior rectus and posterior paraspinal muscle bundles leading to progressive flank herniation, bulge, lumbar spine ligamentous strain, and lower back pain.

LAW defects may arise as congenital defects, traumatic injury, by direct surgical wounding or as a result of oncologic resection.1,2 True LAW congenital defects are far less common than midline defects, gastroschisis, or omphaloceles, and account for < 1% of all congenital abdominal wall defects.3 Iatrogenic abdominal wall defects can arise from any incision that causes either deinnervation of external oblique, internal oblique, or transverse abdominis muscle fibers or disinsertion of the their common origin in the paraspinal region or the insertion at the linea semilunaris. Often, there is an overlapping injury pattern as is the case with retroperitoneal access incisions for renal or vascular surgery where the muscular origin is disrupted and the proximal nerve fibers are transected.4,5,6 In addition, Kocher and Chevron incisions in hepatobiliary surgery, oncologic resections, and lateral abdominal wall traumatic injuries result in subcostal hernias and bulges due to the disruption of the segmental innervation to the oblique muscle complexes. This is a result of the overlapping spinal nerve root contributions with T7–T12 innervating the external oblique, internal oblique, and rectus abdominis transverse abdominis muscles.7

It is important to consider the different anatomic subdivisions of the LAW to appreciate the various defects and their unique presentations. LAW defects can be characterized by anatomic region paramedian, lateral, subcostal, and paraspinal defects. Paramedian defects involve the linea semilunaris with an intact linea alba including the Spigelian hernia.8 Lateral defects involve the oblique muscle complexes in their midsubstance as well as their attachment to the iliac crest inferiorly and the costal margin superiorly. Both paramedian and lateral defects can extend inferiorly to involve the inguinal region. Subcostal defects involve the upper abdomen, chest wall, and in cases of oncologic resection, the underlying diaphragm. Paraspinal defects generally involve the origin of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominis muscles and manifest as lumbar defects involving the retroperitoneum and posterior chest wall. Lumbar triangle hernia defects in this region include Grynfeltt and Petit hernias. Grynfeltt hernias are located in the superior lumbar triangle, which is an inverted triangular space bounded by the posterior border of the internal oblique muscle anteriorly, the anterior border of the paraspinal muscle bundle posteriorly, and the 12th rib superiorly. Petit hernias are located in the inferior lumbar triangle, which is an upright triangular space bounded by the posterior border of the external oblique muscle anteriorly, the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle posteriorly, and the iliac crest inferiorly.9

Challenges in LAWR arise directly from the asymmetric distortion of the abdominal wall. There is an imbalance of distraction forces on the defect and subsequent repair due to the off-center location of the defect. The preserved ipsilateral rectus abdominis muscle complex and the contralateral hemiabdominal wall contract in unison and exploit the laterally located defect as the weakest point in the abdominal wall. In addition, the ratio of muscle to fascia is higher in the LAW than in the central abdominal wall. Thus, the inherent tensile integrity of the soft tissue surrounding of any LAW repair is less than the central abdominal wall. Also, defects in the LAW represent a multilamellar muscular disruption in contrast to the multilamellar-fascial disruption seen in midline ventral hernias. This causes further weakening of the muscular tone of the hemiabdominal wall ipsilateral to the defect. In addition, the obliquely oriented nerve supply to the transverse and oblique muscle complexes results in a deinnervation injury affecting the medial muscle further weakening the LAW over time. As a result, it is nearly impossible to create a truly dynamic contoured reconstruction in the LAW. In the central abdominal wall, centralizing the rectus abdominis complexes and offloading of tension on the repair with a bilateral component separation release establishes a balanced dynamic structurally sound repair. This is not possible in LAW. The options for reconstruction are to provide a static repair that will not attenuate and form a bulge or hernia over time. The reconstruction is planar as opposed to the curvilinear or convex form of the native LAW. The goal is to reinforce the entire hemiabdominal wall with fixation to anatomic structures that will not stretch or attenuate over time.

Operative Techniques

The core surgical principles of ventral hernia repair apply to lateral abdominal wall reconstruction. These include inlay mesh repair and myofascial reapproximation to create a dual layer closure and establish physiologic tension across the abdominal wall closure.10,11 However, LAW repair is quite different from central abdominal wall repair. Often, a dual layer repair with fascial support is not possible due to the paucity of aponeurotic fascia in the LAW and the unavailability of techniques to mobilize the oblique muscle complexes as component separation allows mobilization of the rectus muscle complexes. Thus, often the mesh repair must be placed as a single-layer interposition bridging repair, as often a second layer myofascial coverage is not possible. When the interposition mesh repair is sutured to the bordering deinnervated muscle, a progressive myofascial bulge develops. Similarly, onlay mesh repairs of LAW hernias and bulges produce a static bridge across the defect, but do not address the peripheral muscle attenuation. This type of repair has a high recurrence rate due to the fact that the underlying muscle deinnervation and progressive muscle laxity has not been compensated for in the repair. Thus, the strategy in LAW repair is to avoid patching the defect with mesh in favor of reinforcing the entire LAW with mesh. This is accomplished through an inlay (intraabdominal) mesh placement with the mesh sutured to stable points of fixation beyond the bordering oblique muscle complexes. The mesh should be affixed to innervated musculofascia, lamellar aponeurotic tissue, or bone. Thus, with this technique, hernias, bulges, and full-thickness defects are all treated similarly (Fig. 1).

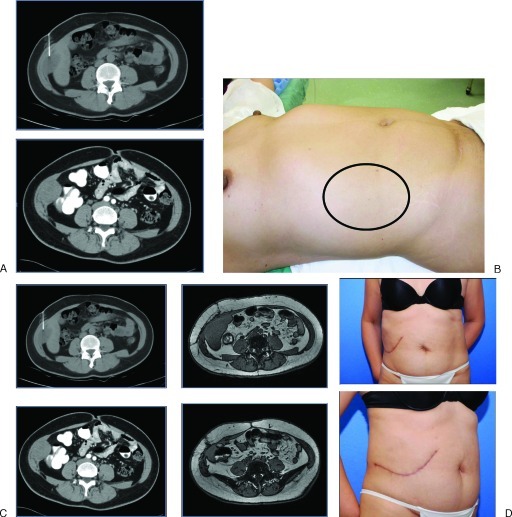

Figure 1.

A 46-year-old woman with a desmoid tumor invading the right lateral abdominal wall transverse abdominis and internal/external oblique muscle complexes. (A) Computed tomography (CT) scans show tumor extending to the inferior border of the liver. (B) The preoperative photo shows the planned margins for a full thickness lateral abdominal wall resection. The patient was reconstructed with an inlay mesh and fasciocutaneous advancement flaps. (C) Follow-up CT scans at 6 months show preservation of the curvilinear contour of the lateral abdominal wall. (D) Patient photo reveals aesthetic contour of the torso is preserved.

The concept of anchoring a mesh repair to stable fixation points in the lateral abdominal wall is a key element of a successful repair. The lateral abdominal wall pillars are stable fixation points—lines of strength and stability. An analogy can be made with craniofacial surgery in that the maintenance of the structural integrity of the facial skeleton relies on the facial buttresses or pillars. In the lateral abdominal wall, these include the costal margin and rib superiorly, the linea semilunaris anteromedially, the inguinal ligament and iliac crest inferiorly, and the investing lumbar and paraspinal fascia posteriorly. To achieve a stable repair, it is important to create an inlay mesh inset that links these anatomic structures. Options for anchoring mesh to the iliac crest depend on the degree and quality of oblique muscle tendon and periosteum that is preserved. Fixation techniques include direct suture to periosteum, transosseous suture placement through preplaced drill holes, or unicortical bone anchor sutures. In addressing the chest wall, the mesh will need to be anchored to the rib cage and costal margin. Options for fixation to rib include circumcostal suture (placement over the superior boarder of the rib) or transcostal placement through predrilled holes.

Managing the Interface between the Diaphragm and Lateral Abdominal Wall

The boundaries to the undersurface of the LAW include the diaphragm, retroperitoneum, and inguinal region. Lateral subcostal full-thickness resections of LAW and costal margin require specific attention to the management of the diaphragm. Subcostal defects that affect the costal margin with associated rib resection involve the underlying insertion of the diaphragm and the diaphragmatic sulcus. The internal boundary between the thoracic and abdominal cavities must be preserved in addition to reestablishing the continuity of the musculoskeletal chest wall and abdominal wall. This adds an element of three-dimensional complexity to reconstructing the LAW, chest wall, and diaphragm. Small peripheral diaphragmatic defects can be repaired by direct suturing of the diaphragm to the cut edge of the rib cage. Large-scale diaphragmatic defects can be managed by elevating the diaphragm and incorporating it into the external musculoskeletal thoracoabdominal wall (Fig. 2). An adjunct to this maneuver is the utilization of mesh as an inlay under both the diaphragm and thoracoabdominal wall. Transcostal or circumcostal sutures are placed through the diaphragm then through the mesh anchoring the mesh–diaphragm construct to the bony chest wall. As a result, the diaphragm is reinforced and extended by the mesh elevating and anchoring the diaphragm to the next most superior rib. Thus, an internal partition is created between the thoracic and abdominal cavities in continuity with the external lateral abdominal wall (Fig. 3).

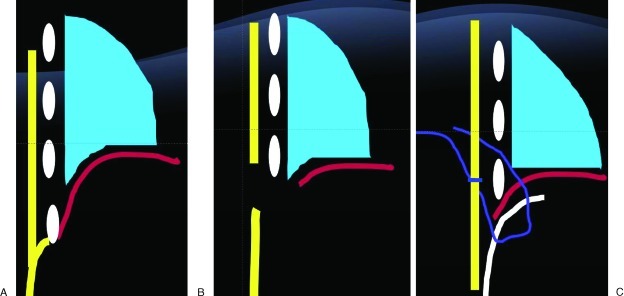

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of diaphragmatic defect. (A) Chest wall and abdominal wall soft tissue are represented in yellow. Diaphragm represented in red. (B) Full-thickness resection of chest wall, abdominal wall, and diaphragm in lower rib with complete loss of the boundaries between the abdominal cavity and the thoracic cavity in addition to the musculoskeletal thoracoabdominal wall. (C) Reconstruction with mesh inlay serving to partition both the thoracic and abdominal cavity, in addition to reinforcing the musculoskeletal thoracoabdominal wall. Mesh represented in white. The mesh is inset below the diaphragm, which is elevated to the level of the next cephalad rib. Circumcostal sutures are placed in a mattress fashion first through the diaphragm then through the mesh, so that the mesh acts to reinforce the diaphragmatic repair as it is anchored to the chest wall.

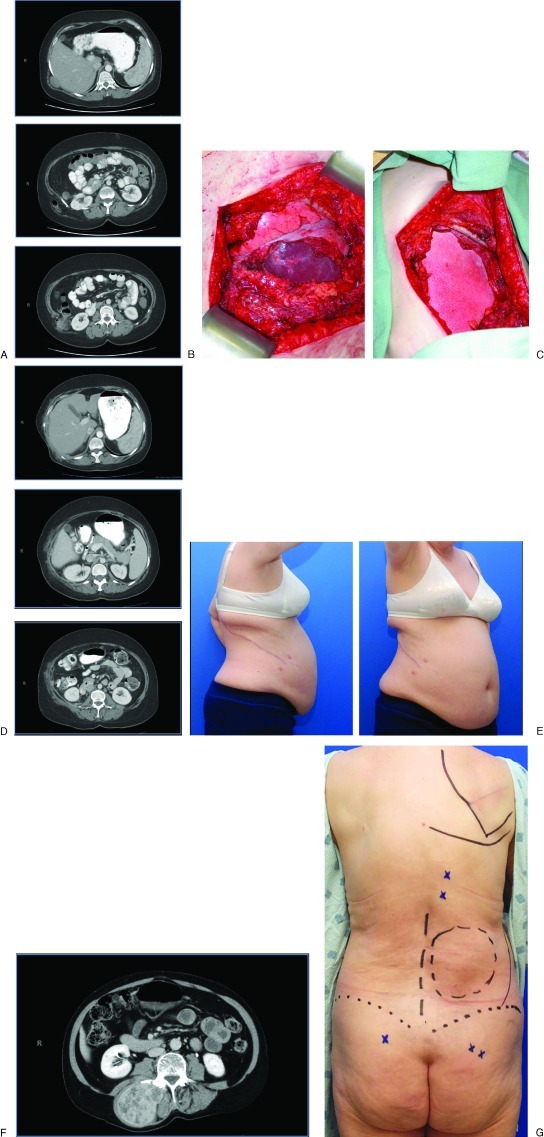

Figure 3.

A 58-year-old woman with recurrent liposarcoma and symptomatic flank hernia planned to undergo radical resection and hernia repair. (A) Computed tomography (CT) scans show tumor involving the lateral abdominal wall abutting the liver with a hernia involving the colon inferiorly. (B) Full-thickness thoracoabdominal wall defect including the diaphragmatic recess. The lung diaphragm and liver are seen in the base of the wound. (C) Bioprosthetic mesh inlay interposition repair combining diaphragmatic repair with lateral abdominal wall hernia repair. (D) 6-month follow-up CT scans. Note preservation of lateral abdominal wall contour and mesh support of liver, colon, and kidney. (E) Lateral and oblique views.

Managing the Interface between the Retroperitoneum and the Posterior Lateral Abdominal Wall

Posterior lateral abdominal wall defects that involve the retroperitoneum merit separate discussion. The anatomic boundaries of the posterior abdominal wall are the paraspinal muscles, quadratus lumborum, and iliopsoas muscles. When these muscular layers have been resected, divided, or deinnervated, their continuity must be restored to prevent a lumbar hernia or bulge. The goal is to support the retroperitoneal viscera and redefine the retroperitoneal reflection to prevent solid organ migration, and adrenal/kidney and colonic herniation. In addition to the musculoskeletal structural boundaries, the posteromedial insertion of the diaphragm, spine, aorta, and vena cava make the inset of a mesh repair technically challenging. A true mesh inlay repair may not be feasible due to the proximity of these neurovascular structures bordering the retroperitoneal defect. In this situation, the mesh can be placed in an onlay fashion. When a significant dead space exists after reinforcement of the retroperitoneal boundary, a soft tissue flap can be included to obliterate the dead space and buttress the mesh repair externally (Fig. 4).

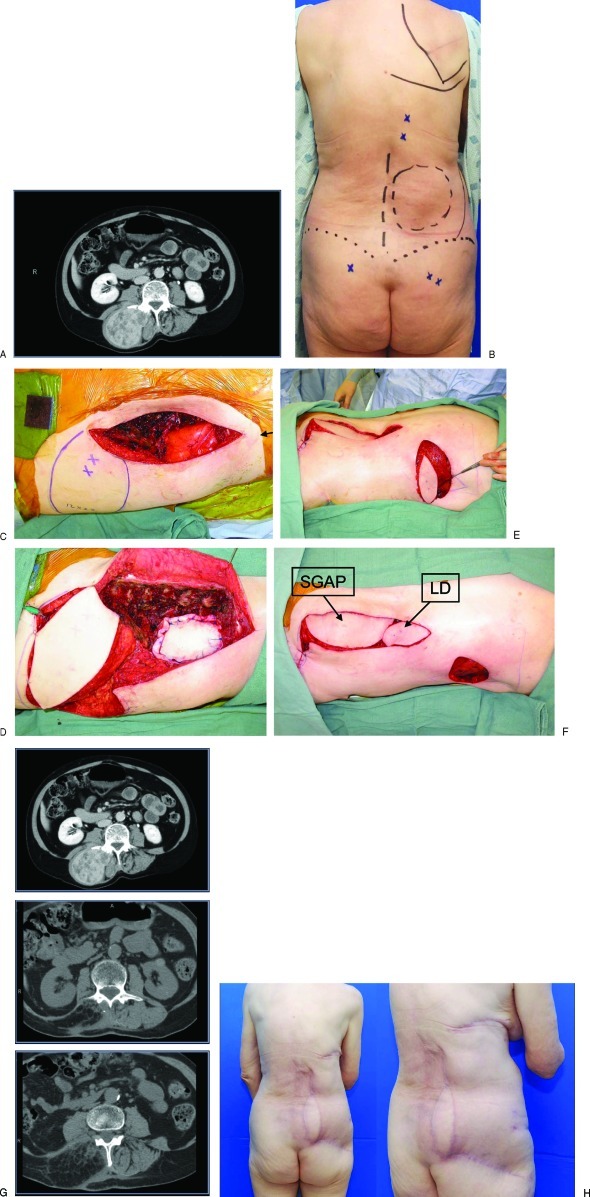

Figure 4.

A 72-year-old woman developed a malignant peripheral nerve sheath sarcoma and will require adjuvant radiation therapy. (A) A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating involvement of the paraspinal muscle bundle and posterolateral abdominal wall. (B) Preoperative view of planned resection. Gluteal perforators and posterior intercostal perforators identified. (C) Full-thickness defect involving the posterolateral abdominal wall to the level of the Gerota fascia. (D) Mesh onlay repair of posterior retroperitoneal defect with support of the right kidney. Soft tissue reconstruction of a large volumetric defect of the posterolateral abdominal wall with pedicled superior gluteal artery perforator flap (SGAP). (E) Reverse latissimus flap (LD) transposed on a posterior intercostal artery perforator to obliterate the dead space in the superior pole of the wound. (F) Inset of the SGAP and LD flaps. (G) 12-month follow-up CT scans demonstrating preservation of the contour of the posterolateral abdominal wall and adequate soft tissue volume replacement. (H) Posterior and oblique photos.

Mesh Utilization in Lateral Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

LAW reconstructions generally require mesh placement to ensure the structural integrity of the repair. There are clinical scenarios when primary fascial closure over a mesh construct is feasible as in the case of chronic hernia repairs where the redundant hernia sac can be used to insulate the underlying mesh. However, the availability of adjacent myofascial tissue as a second layer of closure is limited and an interposition repair must be performed. Surgeon preference and the variables of any given clinical scenario will determine whether bioprosthetic mesh or prosthetic mesh is implanted. Regardless of mesh type, the expectations are that the mesh maintains the lateral abdominal wall contour and does not attenuate leading to a hernia or bulge. In addition, the mesh should be able to interface with the underlying visceral without forming extensive adhesions or erosion, which can lead to fistulization. Prosthetic and bioprosthetic meshes can meet these expectations and the decision to use either is based on patient comorbidities, wound contamination, prior radiation, availability of omentum, and the quality of the overlying soft tissue.

Bioprosthetic mesh materials have advantages over synthetic mesh in certain clinical situations.12 Bioprosthetic repair sites heal by tissue regeneration rather than by scar tissue formation. Once revascularized and remodeled, there is theoretically no longer a foreign body response to the mesh. This reduces the risk of chronic infection and subsequent erosion through the skin or viscera. Intraabdominal adhesions have been reported to be less frequently encountered with bioprosthetic than with synthetic mesh. Thus, bioprosthetic mesh can be placed in direct contact with bowel. An additional advantage is that cutaneous exposure of bioprosthetic mesh can typically be managed with local wound care, rather than explantation of the entire mesh construct as is the case with prosthetic mesh.13 This is the distinct advantage of bioprosthetic mesh when an interposition bridging repair is performed and wound infection or delayed wound healing results in mesh exposure.

Many surgeons prefer to implant a bioprosthetic mesh instead of a prosthetic mesh in a contaminated operative field. This is due to the ability of the bioprosthetic mesh to revascularize and incorporate in the face of bacterial contamination.13 Another advantage of bioprosthetic mesh is realized at the time of reoperation. A bioprosthetic mesh repair site can be incised and closed in as if it were primary fascia (either early after repair or after implant remodeling) as the fascial repair site appears and functions like native fascia. The paramount concerns with the use of bioprosthetic mesh are lack of long-term clinical outcome data and cost in comparison to prosthetic mesh alternatives.14

Soft Tissue Flap Coverage

The success of any LAW reconstruction depends on a stable wound-healing environment. Durable soft tissue coverage is required to insulate the mesh construct to avoid mesh exposure, reduce the risk of seroma formation, periprosthetic infection, and subsequent explantation. The goals of soft tissue coverage are to achieve a tension-free closure and obliterate any potential dead space. This can generally be accomplished in the torso by local fasciocutaneous flap advancement. The overlapping angiosomes of the lateral abdominal wall cutaneous blood supply allow for wide undermining and skin advancement. In addition, tissue expansion can be performed in the trunk to increase the surface area and availability of local soft tissue fasciocutaneous flaps to avoid a pedicled or free flap donor site. In cases of prior radiation, prior surgery, or excessive skin resection, a pedicled regional or free flap may be required to provide adequate soft tissue coverage.

Options for pedicled flaps in the upper abdomen include vertical rectus abdominis flaps (VRAM), latissimus flaps, and omental flaps. Thigh-based flaps including anterolateral thigh flaps (ALT), vastus lateralis flaps, and tensor fascia lata (TFL) flaps are able to reach the lower abdomen and flank as pedicled flaps. If a pedicled flap is not available or feasible, a thoracoepigastric bipedicled fasciocutaneous flap may provide a local tissue alternative and avoid a free tissue transfer. When the volume of tissue loss or the arc of rotation preclude pedicled flap transfer, a free flap is required for stable soft tissue coverage. The thigh can serve as a source of fasciocutaneous flaps and myocutaneous flaps that provide large skin paddles and significant muscle volume for transfer. Recipient vessels in the lateral abdominal wall include the deep inferior epigastric vessels, superior epigastric vessels, internal mammary vessels, intercostal artery perforators, and thoracolumbar perforators. When no local recipient vessels are available vein grafts to the internal mammary or femoral vessels may be required.

Conclusion

Lateral abdominal wall reconstruction requires an understanding of the anatomy, physiologic forces, and the impact of deinnervation injury to design and perform successful reconstructions of hernia, bulge, and full-thickness defects. Operative technique must focus on stabilization of the LAW to nonyielding points of fixation at the anatomic borders of the LAW far beyond the musculofascial borders of the immediate defect. Thus, hernias, bulges, and full-thickness defects are approached in a similar fashion. Mesh reinforcement is uniformly required in LAW reconstruction. Inlay mesh placement with overlying myofascial coverage is preferred as a first-line option as is the case in anterior abdominal wall reconstruction. However, the interposition bridging repairs are often performed as the surrounding myofascial tissue precludes a dual-layered closure. This is more commonly encountered in traumatic and oncologic defects than in hernia defects. The decision to place bioprosthetic or prosthetic mesh depends on surgeon preference, patient comorbidities, and clinical factors of the repair. Regardless of mesh type, the overlying soft tissue must provide stable cutaneous coverage and obliteration of dead space. In cases where the fasciocutaneous flaps surrounding the defect are inadequate for closure, regional pedicled flaps or free flaps are recruited to achieve stable soft tissue coverage.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Butler has served as a consultant for LifeCell Corporation in Branchburg, New Jersey.

References

- 1.Bender J S, Dennis R W, Albrecht R M. Traumatic flank hernias: acute and chronic management. Am J Surg. 2008;195(3):414–417, discussion 417. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burt B M, Afifi H Y, Wantz G E, Barie P S. Traumatic lumbar hernia: report of cases and comprehensive review of the literature. J Trauma. 2004;57(6):1361–1370. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000145084.25342.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakhry S M, Azizkhan R G. Observations and current operative management of congenital lumbar hernias during infancy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;172(6):475–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee S, Nam R, Fleshner N, Klotz L. Permanent flank bulge is a consequence of flank incision for radical nephrectomy in one half of patients. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(1):36–39. doi: 10.1016/S1078-1439(03)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsen S L, Krosnick T A, Roseborough G S. et al. Preoperative and intraoperative determinants of incisional bulge following retroperitoneal aortic repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2006;20(2):183–187. doi: 10.1007/s10016-006-9021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nanni G, Tondolo V, Citterio F. et al. Comparison of oblique versus hockey-stick surgical incision for kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(6):2479–2481. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutherland R S, Gerow R R. Hernia after dorsal incision into lumbar region: a case report and review of pathogenesis and treatment. J Urol. 1995;153(2):382–384. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199502000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celdrán A, Señaris J, Mañas J, Frieyro O. The open mesh repair of Spigelian hernia. Am J Surg. 2007;193(1):111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salameh J R, Salloum E J. Lumbar incisional hernias: diagnostic and management dilemma. JSLS. 2004;8(4):391–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stumpf M, Conze J, Prescher A. et al. The lateral incisional hernia: anatomical considerations for a standardized retromuscular sublay repair. Hernia. 2009;13(3):293–297. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen S, Schuster F, Steinbach F, Henke G, Hellmich G, Ludwig K. Sublay prosthetic repair for incisional hernia of the flank. J Urol. 2002;168(6):2461–2463. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler C E. The role of bioprosthetics in abdominal wall reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(2):199–211, v–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler C E, Langstein H N, Kronowitz S J. Pelvic, abdominal, and chest wall reconstruction with AlloDerm in patients at increased risk for mesh-related complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(5):1263–1275, discussion 1276–1277. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000181692.71901.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin J, Rosen M J, Blatnik J. et al. Use of acellular dermal matrix for complicated ventral hernia repair: does technique affect outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(5):654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]