Abstract

Background

Impaired airway mucosal immunity can contribute to increased respiratory tract infections in asthmatic patients, but the involved molecular mechanisms have not been fully clarified. Airway epithelial cells serve as the first line of respiratory mucosal defense to eliminate inhaled pathogens through various mechanisms, including Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways. Our previous studies suggest that impaired TLR2 function in TH2 cytokine–exposed airways might decrease immune responses to pathogens and subsequently exacerbate allergic inflammation. IL-1 receptor–associated kinase M (IRAK-M) negatively regulates TLR signaling. However, IRAK-M expression in airway epithelium from asthmatic patients and its functions under a TH2 cytokine milieu remain unclear.

Objectives

We sought to evaluate the role of IRAK-M in IL-13–inhibited TLR2 signaling in human airway epithelial cells. Methods: We examined IRAK-M protein expression in epithelia from asthmatic patients versus that in normal airway epithelia. Moreover, IRAK-M regulation and function in modulating innate immunity (eg, TLR2 signaling) were investigated in cultured human airway epithelial cells with or without IL-13 stimulation.

Results

IRAK-M protein levels were increased in asthmatic airway epithelium. Furthermore, in primary human airway epithelial cells, IL-13 consistently upregulated IRAK-M expression, largely through activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Specifically, phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation led to c-Jun binding to human IRAK-M gene promoter and IRAK-M upregulation. Functionally, IL-13–induced IRAK-M suppressed airway epithelial TLR2 signaling activation (eg, TLR2 and human β-defensin 2), partly through inhibiting activation of nuclear factor κB.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that epithelial IRAK-M overexpression in TH2 cytokine–exposed airways inhibits TLR2 signaling, providing a novel mechanism for the increased susceptibility of infections in asthmatic patients.

Keywords: IL-13, IL-1 receptor–associated kinase M, Toll-like receptor 2, airway epithelial cells

Asthma prevalence is predicted to increase globally by 50% every decade.1 Approximately 300 million persons worldwide have asthma. Asthmatic patients have increased susceptibility to respiratory tract bacterial infections, which frequently cause acute exacerbations of the disease, significantly increase health care costs, and negatively affect the quality of life of the patients and their families.2 Although several studies have suggested that impaired airway mucosal immunity might account for the frequent airway bacterial infections seen in asthmatic patients,3,4 the involved molecular mechanisms have not been fully clarified.

Airway epithelial cells represent the first line of respiratory mucosal defense to eliminate inhaled pathogens through various mechanisms, including Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways.5,6 For example, human airway epithelial cells respond to bacterial lipopeptide with induction of the antimicrobial peptide human β-defensin 2 (hBD2) in a TLR2-dependent manner.7 Our previous studies have demonstrated that ovalbumin-induced airway allergic inflammation or TH2 cytokines (eg, IL-4 and IL-13) significantly impair TLR2 expression and IL-6 production in lung cells (eg, dendritic cells), which delays clearance of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from murine lungs.8 Furthermore, adenovirus-mediated TLR2 gene transfer to airway epithelial cells of Tlr2−/− mice significantly primes host defense against M pneumoniae, indicating that therapy aimed at enhancing dampened airway epithelial TLR2 signaling in patients with chronic lung diseases (eg, asthma) would be beneficial in the eradication of airway pathogenic bacteria.9 The above studies strongly suggest that reduction in or lack of TLR2 function in airways might contribute to acute asthma exacerbations by rendering hosts more susceptible to infections with pathogens containing TLR2 ligands.

The TH2 response is a prominent feature of allergic diseases, including asthma. Among TH2 cytokines, IL-13 is considered particularly critical to asthma immunopathogenesis.10,11 Previous studies suggest that IL-4 and IL-13 impair the expression and function of hBD2 and hBD3 in human epidermal keratinocytes, which might account for the increased susceptibility to skin infections seen in patients with atopic dermatitis.12,13 Furthermore, IL-4 and IL-13 directly reduce levels of the innate immune molecules TLR9 and hBD2 in human sinonasal epithelial cells and might contribute to microbial colonization in the nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis.14 In addition, IL-4 and IL-13 downregulate TLR4 expression in a human intestinal epithelial cell line.15 However, these publications did not provide detailed molecular mechanisms underlying TH2 cytokine–mediated impairment of innate immunity.

IL-1 receptor–associated kinase M (IRAK-M), also known as IRAK-3, negatively regulates TLR signaling and associated inflammation.16 The IRAK-M gene is located to chromosome 12q14.2,17 a region that is repeatedly shown to have linkage to asthma and IgE levels.18,19 Recently, Balaci et al20 have revealed that a variation within the IRAK-M gene is associated with early-onset persistent asthma. They have shown that IRAK-M protein is expressed in alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells of healthy human lungs. Their results challenge the previous findings that human IRAK-M is specifically expressed in monocytes and macrophages. 21,22 However, it remains unknown whether epithelial IRAK-M expression differs between healthy subjects and asthmatic patients. If so, does the aberrant IRAK-M expression in the airways of asthmatic patients contribute to impaired innate immune responses (eg, TLR2 signaling)?

In this study we hypothesized that IL-13 can upregulate IRAKM expression and subsequently inhibits TLR2 signaling (eg, TLR2 and hBD2 expression) in human airway epithelial cells. First, we demonstrated upregulation of IRAK-M protein in epithelium from asthmatic patients versus that found in normal airway epithelium. Second, we verified that IL-13 could induce IRAK-M expression in air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of primary human bronchial epithelial cells. Third, we revealed that c-Jun directly bound to the human IRAK-M gene promoter on IL-13 stimulation in human airway epithelial cells. Lastly, we defined a critical role of IRAK-M in IL-13–impaired TLR2 signaling in human airway epithelial cells.

METHODS

For further details, see the Methods section in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

IRAK-M immunohistochemistry staining in human endobronchial biopsy specimens

Endobronchial biopsy specimens of healthy subjects (n = 4) or patients with mild-to-moderate asthma (n = 6) were obtained through bronchoscopy, and the subjects’ characteristics have been described in our previous publications.23–26 Our research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Jewish Health. Tissue sections were stained with rabbit anti-human IRAK-M (Millipore, Temecula, Calif) or control rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif), and the IRAK-M–stained area in airway epithelium was analyzed.25

ALI cultures of human brushed bronchial epithelial cells

Human primary bronchial epithelial cells were obtained from endobronchial brushings from healthy nonsmoking subjects (n = 4) and patients with mild-to-moderate asthma (n = 6), and the clinical characteristics have been described in our previous publication.27 Our research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Jewish Health. Epithelial cell ALI cultures were performed as previously reported.27 On day 10 of ALI culture, cells were treated with BSA or 10 ng/mL recombinant human IL-13 (rhIL-13; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn) for 7 days and then lysed for IRAK-M and TLR2 Western blotting.

ALI cultures of normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells for mechanistic studies of IL-13–induced IRAK-M expression

Normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells were obtained from tracheas and bronchi of deidentified organ donors by digesting the tissue with 0.2% protease solution and then subjected to ALI cultures, as described above. On day 10 of ALI culture, cells were treated with (1) BSA or 10 ng/mL rhIL-13 for up to 120 minutes. Then, cells were lysed for phospho-Akt and total Akt Western blotting or (2) BSA or 10 ng/mL rhIL-13 for 6 days. Thereafter, cells were treated with BSA or rhIL-13 in the absence or presence of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin (100 nmol/L; Cell Signaling, Danvers, Mass) for 2 hours to measure phospho–c-Jun levels or for 24 hours (a total of 7 days of IL-13 treatment) to quantify IRAK-M and TLR2 proteins by using Western blotting.

c-Jun activity assay in normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cell cultures

Normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells under submerged culture conditions were treated with BSA or 10 ng/mL rhIL-13 for up to 120 minutes. Nuclear c-Jun activity was analyzed by using an ELISA-based TransAM activator protein 1 (AP-1)/c-Jun activation assay (Active Motif, Carlsbad, Calif).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis

Normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells under submerged culture conditions were treated with BSA or 10 ng/mL rhIL-13 for 2 hours. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis28,29 was performed by using a mouse anti–c-Jun antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif) or control murine IgG. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by using quantitative real-time RT-PCR with the SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif) and primers that cover human IRAK-M gene promoter region containing the putative AP-1/c-Jun binding site. All values were normalized to input DNA and expressed as the fold induction in chromatin enrichment with the c-Jun antibody to indicate c-Jun binding intensity.

IRAK-M gene knockdown in normal human brushed bronchial epithelial cells

Human IRAK-M short hairpin RNA (shRNA) encoded in pLL3.7 was generated as previously described.30,31 Briefly, epithelial cells under immersed conditions were transduced with either pLL3.7-shLUC (an irrelevant gene control) or pLL3.7–shIRAK-M once daily for 3 consecutive days. Fortyeight hours after the last transduction, IRAK-M gene knockdown was verified at both the mRNA and protein levels. The remaining cells were used for ALI culture, as described above. On day 10 of ALI culture, cells were treated with BSA or 10 ng/mL rhIL-13 for 6 days. Then cells were treated for 24 hours with BSA or rhIL-13 with or without 100 ng/mL of the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4 (InvivoGen, San Diego, Calif). Thereafter, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) p65 activity, TLR2 protein, and apical hBD2 peptide were examined.

Generation of a human lung epithelial cell line stably overexpressing human IRAK-M protein

Human IRAK-M cDNA was obtained from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, Ala) and cloned into a mammalian expression plasmid by means of PCR amplification. Human lung mucoepidermoid carcinoma–derived NCI-H292 cells (clone CRL-1848; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va) were transfected with IRAK-M expression vector or empty vector (control) and maintained in G418 (800 µg/mL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif) selective medium to generate the stable cell line. IRAK-M protein overexpression was confirmed by means of Western blotting. Cells were starved in serum-free medium for 2 hours and then treated with or without Pam2CSK4 at 10 ng/mL for an additional 6 hours to evaluate the effects of IRAK-M on TLR2 signaling. Cells were processed to measure NF-κB p65 activity by using an ELISA-based NF-κB p65 activation assay (Active Motif) and TLR2 protein by means of Western blotting. IL-8 levels in cell supernatants were measured by using a human CXCL/IL-8 DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems) and normalized by cell numbers at the harvest.

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of protein samples were separated on 8% or 10% Precise Protein Gels (Pierce, Rockford, Ill), transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-human IRAK-M (Millipore), mouse anti-human TLR2/CD282 (Imgenex Corp, San Diego, Calif), mouse anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 6C5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-Akt rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling), Akt rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling), or phospho–c-Jun rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling). Blots were then incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase–linked secondary antibodies and Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate. Densitometry was performed with NIH Image-J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for human IRAK-M was performed by using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Hs00200502_m1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was evaluated as an internal positive control. The comparative cycle of threshold (ΔΔCt) method was used to demonstrate the relative mRNA levels of the IRAK-M gene.31

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEMs. One-way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons, and a Tukey post hoc test was applied, where appropriate. The Student t test was used when only 2 groups were compared. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

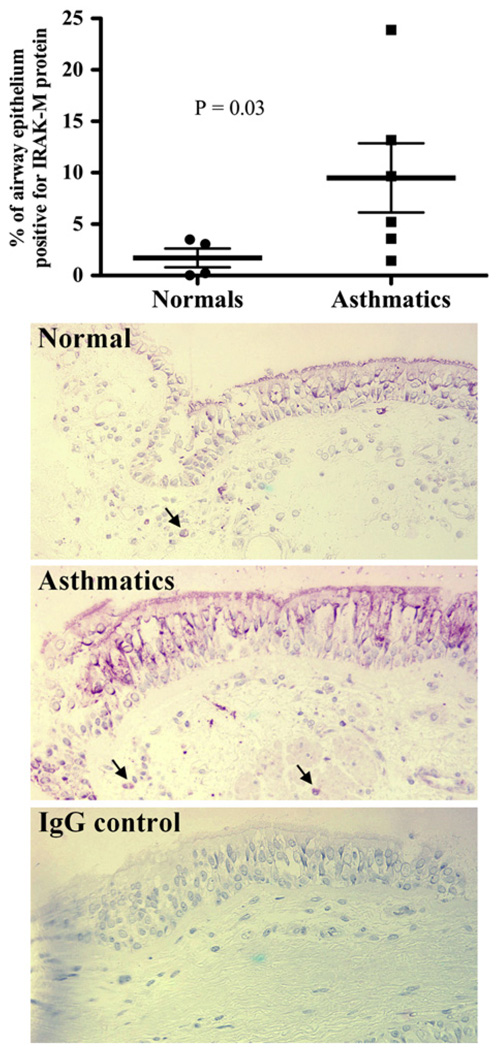

Airway epithelial cells from asthmatic patients express increased IRAK-M protein levels

Immunohistochemistry was performed to examine IRAK-M protein in endobronchial biopsy specimens of healthy subjects and asthmatic patients. As shown in Fig 1, airway epithelial cells from asthmatic patients expressed significantly higher levels of IRAK-M protein than those from healthy subjects. No staining was seen in tissues incubated with control IgG. IRAK-M protein staining in airway epithelium from asthmatic patients was mainly localized to ciliated cells. In addition to bronchial epithelial cells, submucosal inflammatory cells also expressed IRAK-M protein.

FIG 1.

Increased IRAK-M protein expression in airway epithelial cells from asthmatic patients. Upper panel, Airway epithelial IRAK-M protein quantitative data in endobronchial biopsy specimens of healthy subjects (n = 4) and asthmatic patients (n = 6). Lower panel, Representative IRAK-M immunohistochemistry staining in bronchial epithelial cells and submucosal inflammatory cells (black arrows, original magnification ×200). Data are presented as means (thick horizontal lines) ± SEMs.

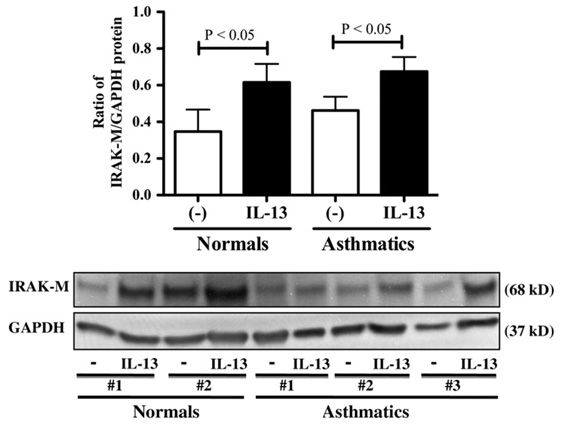

IL-13 induces IRAK-M protein expression in cultured human brushed bronchial epithelial cells

The effect of IL-13 on IRAK-M expression was examined in ALI cultures of brushed bronchial epithelial cells from healthy subjects and asthmatic patients to verify IRAK-M upregulation in airway epithelium from asthmatic patients. As shown in Fig 2, IL-13 significantly increased IRAK-M protein expression in both healthy subjects and asthmatic patients. Furthermore, the baseline of IRAK-M protein expression in asthmatic patients trended to be higher than that in healthy subjects, although it did not reach a statistical significance.

FIG 2.

IL-13 induces IRAK-M protein expression in cultured human brushed bronchial epithelial cells. Upper panel, IRAK-M protein quantitative data (means ± SEM) in healthy subjects (n = 4) and asthmatic patients (n = 6). Lower panel, Representative IRAK-M and GAPDH Western blots.

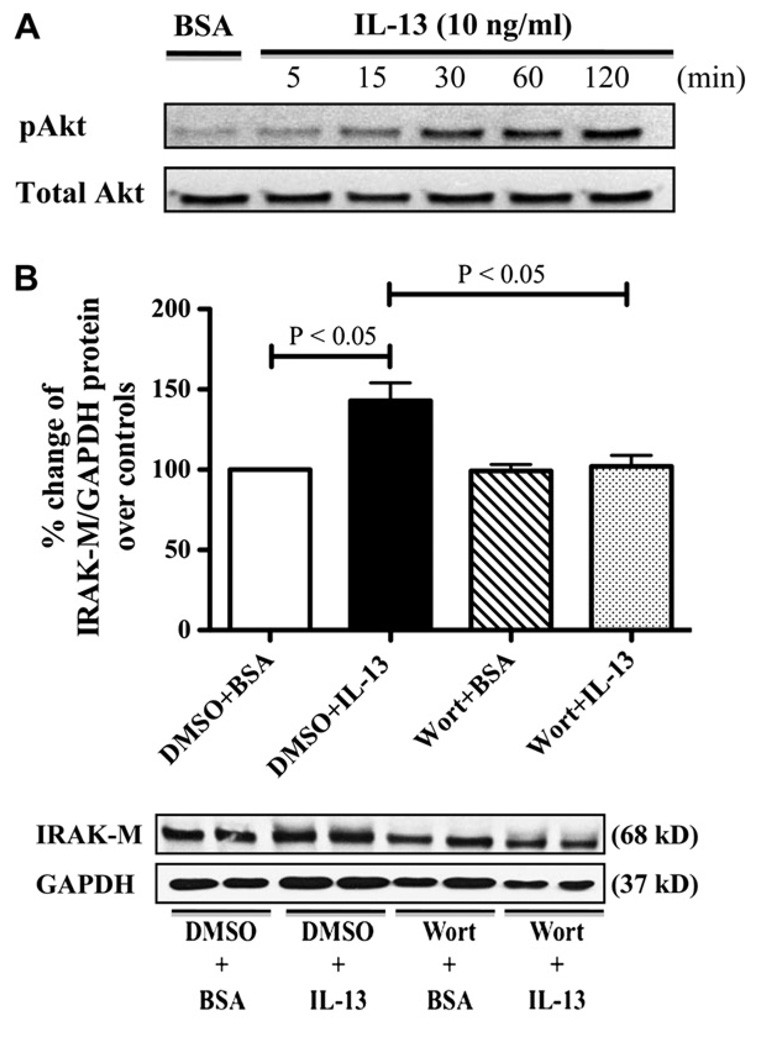

Activation of the PI3K pathway is required for IL-13–induced IRAK-M expression

In our preliminary experiments we validated that well-differentiated normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells have responded similarly to IL-13 regarding IRAK-M expression compared with normal human brushed bronchial epithelial cells. Because of the limited availability of brushed bronchial epithelial cells, we used ALI cultures of normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells for mechanistic studies to define epithelial IRAKM regulation on IL-13 stimulation.

PI3K/Akt phosphorylation in murine tracheal segments contributes to IL-13–induced airway smooth muscle hyperresponsiveness. 32 Moreover, PI3K activation is necessary for IRAK-M upregulation in adiponectin-induced endotoxin tolerance in murine macrophages.33 Therefore we first treated ALI cultures of normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells with BSA or IL-13 at the indicated times and determined Akt activation. IL-13 time-dependently induced phosphorylation of Akt in human primary airway epithelial cells (Fig 3, A). Second, we treated the cells with BSA or IL-13 in the absence or presence of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin and measured IRAK-M protein expression. Pretreatment of wortmannin significantly abolished IL-13–induced IRAK-M expression in human primary airway epithelial cells (Fig 3, B). Together, our data suggest that IL-13 might activate the PI3K/Akt pathway to promote IRAK-M expression in human airway epithelial cells.

FIG 3.

PI3K activation is required for IL-13–induced IRAK-M expression. A, Representative phospho-Akt (pAkt) and total Akt Western blots (n = 3 independent experiments). B, Upper level, IRAK-M protein quantitative data (means ± SEMs) are from 4 independent experiments. Lower panel, Representative IRAK-M and GAPDH Western blots. DMSO, Dimethyl sulfoxide; Wort, wortmannin.

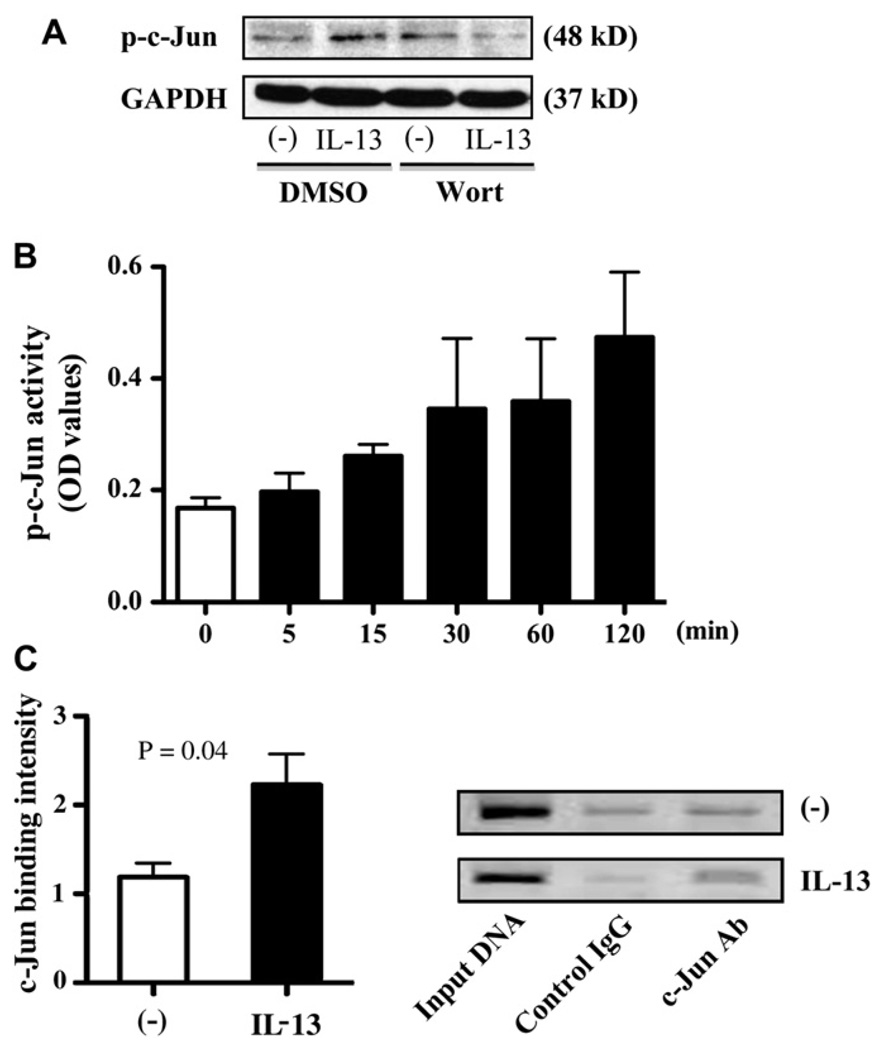

c-Jun directly binds to human IRAK-M promoter on IL-13 stimulation

The PI3K pathway has been shown to modulate its downstream targets, such as AP-1/c-Jun, to regulate gene (eg, IL-6) expression. 34 Our preliminary analysis using the SABiosciences’ Text Mining Application and the UCSC Genome Browser revealed putative AP-1/c-Jun binding sites in the promoter region of the human IRAK-M gene.

First, to study the role of the PI3K pathway in c-Jun activation on IL-13 stimulation, we treated ALI cultures of normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells with BSA or IL-13 in the absence or presence of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin and measured phospho–c-Jun levels. Pretreatment of wortmannin significantly attenuated IL-13–induced c-Jun phosphorylation in human primary airway epithelial cells (Fig 4, A).

FIG 4.

c-Jun directly binds to the IRAK-M gene promoter through PI3K activation on IL-13 stimulation. A, Representative phospho–c-Jun and GAPDH Western blots (n = 4 independent experiments). B, Phospho– c-Jun activity data (means ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments. C, Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Left panel, Increased c-Jun binding to IRAK-M gene promoter after IL-13. Data (means ± SEM) are from 3 independent experiments. Right panel, Representative agarose gel electrophoresis. Ab, Antibody; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Wort, wortmannin.

Second, to verify whether IL-13 directly induces c-Jun phosphorylation, we stimulated the submerged cultures of normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells with BSA or IL-13 for the indicated times and detected c-Jun activity in nuclei. IL-13 timedependently induced c-Jun phosphorylation in human primary airway epithelial cells (Fig 4, B).

Finally, we examined whether c-Jun bound to the human IRAK-M gene promoter by using chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis. As shown in Fig 4, C, compared with chromatin samples from BSA-treated cells, those from IL-13–stimulated cells and immunoprecipitated with c-Jun antibody showed an approximately 1.9-fold increase in the PCR product within the IRAK-M gene promoter region containing the AP-1/c-Jun binding site (−2179 bp to −2350 bp from transcriptional start site).

Collectively, these data indicate that the upregulation of IRAK-M by IL-13 is in part mediated by PI3K/Akt activation and subsequent AP-1/c-Jun binding to IRAK-M gene promoter in human airway epithelial cells.

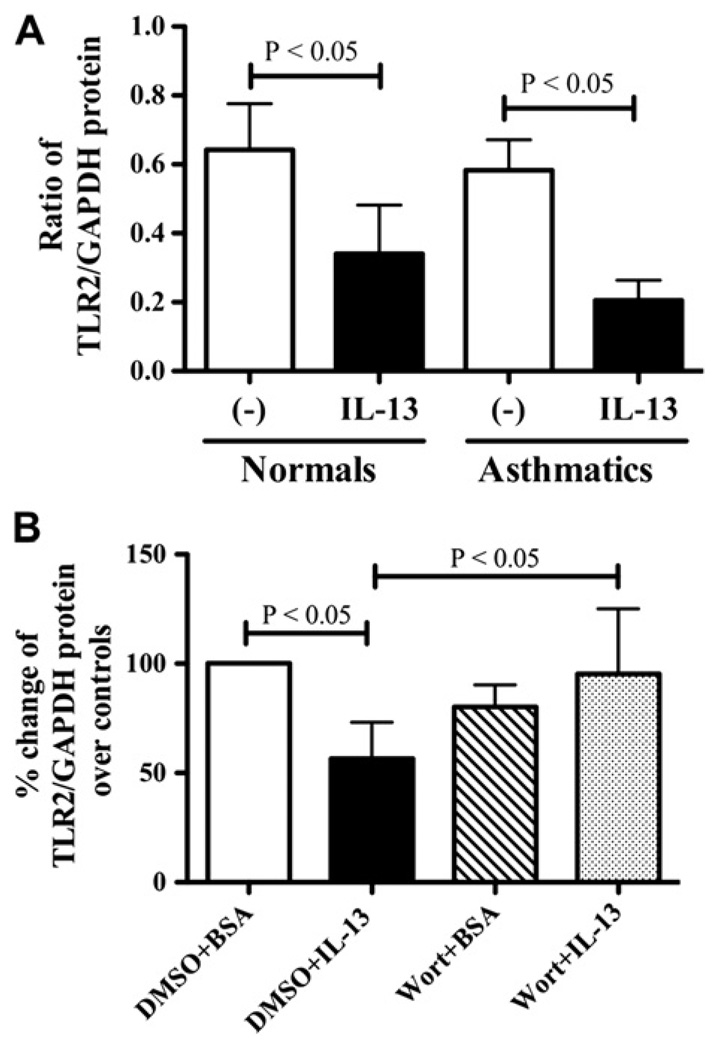

Role of IRAK-M in IL-13–mediated impairment of epithelial TLR2 signaling

To substantiate the negative regulatory role of IRAK-M in airway epithelial innate immunity, we first examined whether epithelial TLR2 expression was affected by IL-13 in ALI cultures of brushed bronchial epithelial cells from healthy subjects and asthmatic patients. We found that IL-13 significantly decreased TLR2 protein expression in both healthy subjects and asthmatic patients. Although TLR2 baseline levels were similar (P >.05) in nonstimulated cells from both subject groups, the reduction in TLR2 protein expression by IL-13 in asthmatic patients was greater than that in healthy subjects, although it did not reach statistical significance (Fig 5, A). In addition, we found that pretreatment of wortmannin significantly restored IL-13–impaired TLR2 protein expression in ALI cultures of normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells (Fig 5, B), which was associated with the significant decrease in IRAK-M protein expression, as described in Fig 3, B.

FIG 5.

IL-13 decreases TLR2 protein expression in human airway epithelial cells. A, TLR2 protein quantitative data in cultured brushed bronchial epithelial cells from healthy subjects (n = 4) and asthmatic patients (n = 6). B, PI3K inhibition restored TLR2 protein expression in IL-13–treated normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells (n = 4). Data are presented as means ± SEMs. DMSO, Dimethyl sulfoxide; Wort, wortmannin.

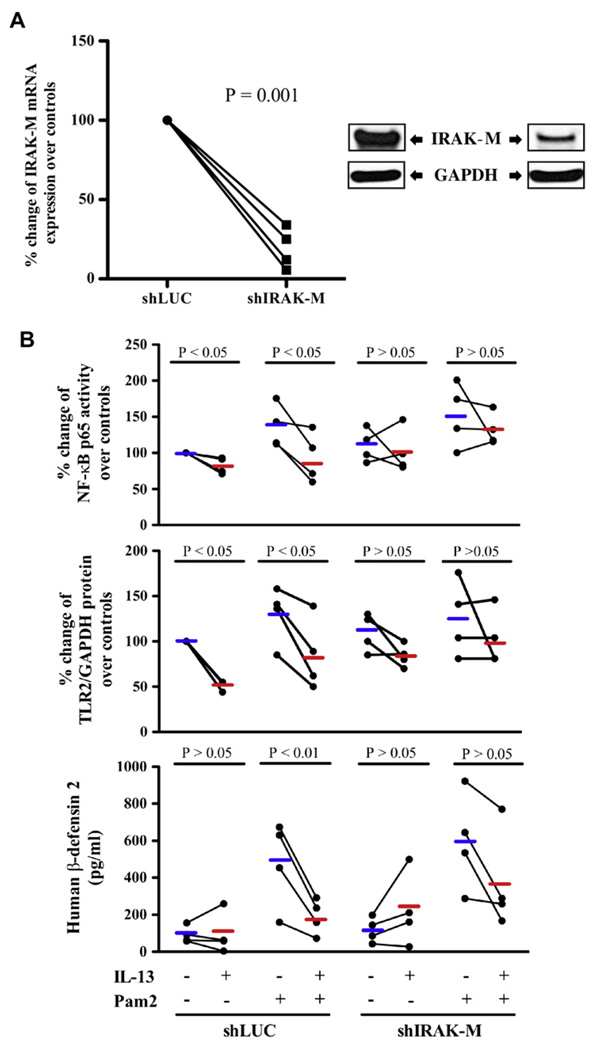

All the observations that reduced TLR2 expression was coupled with increased IRAK-M expression after IL-13 stimulation in human airway epithelial cell cultures led us to hypothesize that TH2 cytokines might dampen epithelial TLR2 function through induction of IRAK-M. To test this hypothesis, we knocked down IRAK-M gene expression in human brushed bronchial epithelial cells followed with BSA or IL-13 treatment in the absence or presence of the TLR2 agonist Pam2CSK4. Compared with the control shLUC vector, shIRAK-M lentiviral vector resulted in about 80% knockdown of IRAK-M mRNA (Fig 6, A, left panel) and protein (Fig 6, A, right panel) expression. As shown in Fig 6, B, IL-13 significantly inhibited Pam2CSK4-induced NFκB p65 activation in shLUC cells but did not suppress NF-κB p65 activation in shIRAK-M cells. Furthermore, the reduction of epithelial IRAK-M expression significantly restored IL-13–impaired TLR2 protein expression. In line with NF-κB and TLR2 data, IL-13 markedly attenuated Pam2CSK4-induced hBD2 production in shLUC (control) cells. However, IRAK-M knockdown significantly abolished IL-13–mediated hBD2 reduction. Correlation analysis was done by using the Pearson correlation coefficient to further demonstrate the role of IRAK-M in regulating NF-κB activity (eg, hBD2 production). An inverse relationship (r = −0.55, P = .028) between IRAK-M expression and hBD2 levels was found.

FIG 6.

Role of IRAK-M in IL-13–mediated impairment of epithelial TLR2 signaling. A, IRAK-M shRNA (shIRAK-M) significantly reduced IRAK-M mRNA (left panel) and protein (right panel) expression compared with the control (firefly luciferase shRNA [shLUC]) in normal human brushed bronchial epithelial cells (n = 4). B, NF-κB p65 activity, TLR2 protein, and human hBD2 peptide levels in normal human brushed bronchial epithelial cells that were transduced with shLUC or shIRAK-M, followed by IL-13, Pam2CSK4 (Pam2), or both treatments (n = 4). Short thick horizontal lines represent means.

Taken together, the above results suggest that IRAK-M contributes to the inhibition of airway epithelial TLR2 signaling activation (eg, TLR2 and hBD2 expression) by IL-13 partly through inhibiting NF-κB activation.

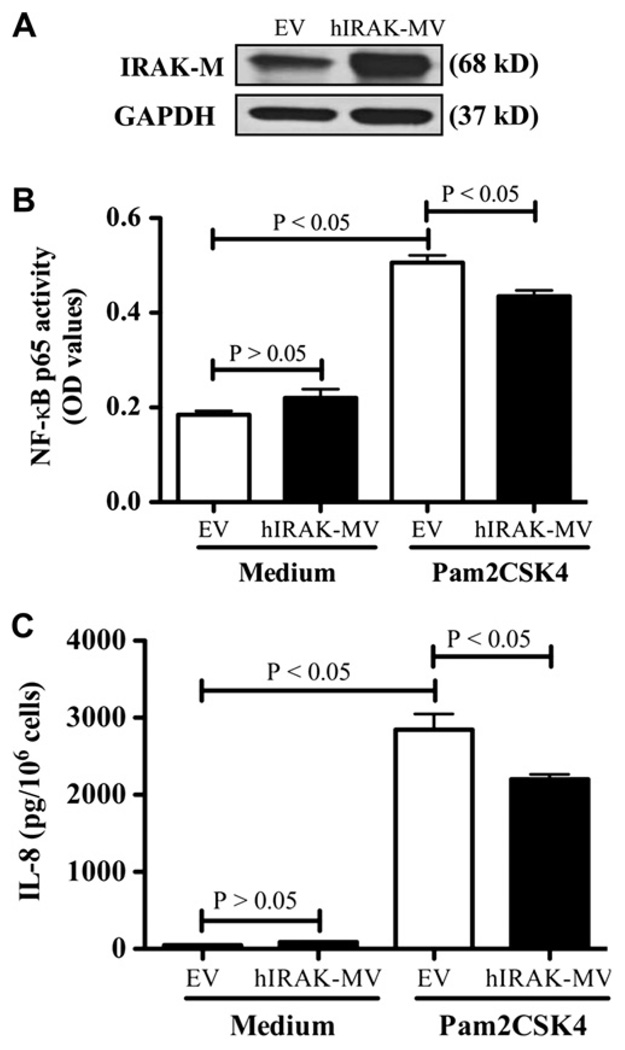

IRAK-M protein overexpression decreases TLR2-mediated IL-8 production in NCI-H292 cells

To further illustrate the direct effect of IRAK-M on epithelial TLR2 signaling activation, we stably overexpressed human IRAK-M protein in NCI-H292 cells because they express much less basal IRAK-M protein compared with normal primary human airway epithelial cells. NCI-H292 cells have negligible hBD2 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. Thus to evaluate activation of the TLR2 pathway, we measured IL-8 production in human IRAK-M–overexpressing NCI-H292 cells with or without Pam2CSK4 stimulation.

First, we confirmed robust overexpression of human IRAK-M protein in NCI-H292 cells stably transfected with human IRAK-M cDNA vector (Fig 7, A). Second, overexpression of human IRAK-M protein significantly decreased Pam2CSK4-induced NF-κB activation (Fig 7, B) and IL-8 secretion (Fig 7, C). However, TLR2 protein expression did not change after 6 hours of Pam2CSK4 treatment. Collectively, these results further suggest an inhibitory role of IRAK-M in innate immune responses (eg, TLR2 agonist–induced NF-κB activation and IL-8 production) in human lung epithelial cells.

FIG 7.

IRAK-M overexpression decreases TLR2 signaling activation in NCIH292 cells. A, Overexpression of human IRAK-M protein was confirmed by using Western blotting. B, NF-κB p65 activity. C, IL-8 protein levels in cell supernatants. Data are from 3 independent experiments and presented as means ± SEMs. EV, Empty vector; hIRAK-MV, human IRAK-M vector.

DISCUSSION

For the first time, we studied the regulation and function of lung epithelial IRAK-M in the context of a TH2 cytokine milieu. We found significantly increased IRAK-M expression in asthmatic airway epithelium. The TH2 cytokine IL-13 consistently upregulated IRAK-M expression in well-differentiated human primary airway epithelial cells. Furthermore, activation of the PI3K pathway was in part responsible for IL-13–induced epithelial IRAK-M expression. Most importantly, IRAK-M was shown to downregulate airway epithelial TLR2 signaling activation.

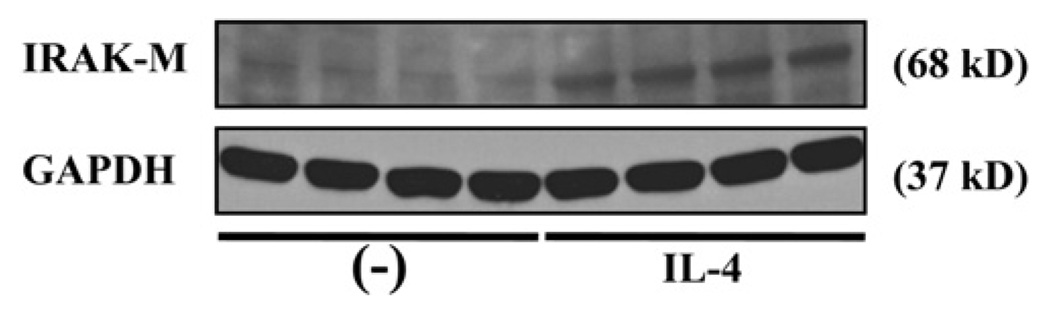

IRAK-M can regulate immune homeostasis and tolerance in a number of infectious and noninfectious diseases by preventing excessive inflammation and tissue damage.35 IRAK-M expression can be induced by a number of molecules, including TLRs (eg, TLR2, TLR4, TLR7, and TLR9), and endogenous or exogenous soluble factors (eg, hormone).35,36 However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no solid evidence of whether TH2 cytokines (eg, IL-13) can induce IRAK-M expression. Although human IRAK-M is generally confined to monocytes and macrophages, our current study has clearly demonstrated that human airway epithelial cells expressed IRAK-M protein, especially in asthmatic patients. Our finding significantly advances the previous study reporting IRAK-M protein expression in lung epithelial cells of healthy donors.20 Furthermore, we have disclosed that IL-13 could remarkably upregulate IRAK-M protein expression in well-differentiated human airway epithelial cells from both healthy subjects and asthmatic patients in vitro. The epithelial IRAK-M induction by IL-13 varied among human subjects, which is consistent with the results of previous studies involving other primary human cells.37,38 Our finding does not support a previous microarray study showing downregulated IRAK-M mRNA expression in human blood monocytes on IL-13 stimulation for 2 and 6 hours.39 This suggests that IRAK-M regulation by IL-13 could be cell type specific. Our current study has focused on the effects of IL-13 on IRAK-M because its level is generally higher than those of other TH2 cytokines, such as IL-4.40,41 However, in a preliminary study we found that IL-4 also increased IRAK-M expression, further suggesting the role of a TH2 cytokine milieu in IRAK-M upregulation (Fig 8).

FIG 8.

IL-4 induces IRAK-M protein expression in cultured normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Representative IRAK-M and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) Western blots of 4 replicates are shown.

Although consistency between mRNA and protein expression of a certain gene is often assumed in many studies, examples of divergent trends are also frequently observed.42–44 In our preliminary experiments IL-13 significantly induced IRAK-M protein expression in human airway epithelial cells at both early (eg, 1 day) and late (eg, 7 days) time points. However, to our surprise, IRAK-M mRNA expression was not always consistent with its protein expression at all the time points. This mRNA versus protein inconsistency might reflect the complexity of molecular regulation of IRAK-M by IL-13, especially with repeated exposures. In addition, posttranslational regulation might also contribute to the mRNA-protein discordance of human epithelial IRAK-M expression after IL-13 exposure. Hence the underlying transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms of IRAK-M gene expression by IL-13 need to be clearly elucidated in future studies.

The role of PI3K pathway activation in IRAK-M expression remains controversial. Escoll et al45 have demonstrated that IRAK-M mRNA is rapidly induced in septic human monocytes in the presence of a PI3K inhibitor. Conversely, induction of IRAK-M expression in murine primary macrophages by adiponectin requires activation of the PI3K pathway.33 However, it is not clear what transcription factors are required for IRAK-M induction after adiponectin-induced PI3K activation. In the present study we demonstrate that IL-13 promotes c-Jun phosphorylation through activation of the PI3K pathway. However, which specific PI3K subunit or subunits are primarily responsible for c-Jun activation remains elusive and warrants future studies. We also showed that c-Jun directly binds to the IRAK-M gene promoter to upregulate epithelial IRAK-M expression.

It is well known thatNF-κBactivation regulates many aspects of the inflammatory response, including TLR expression and antimicrobial peptide hBD2 production.46–51 For the first time, we revealed that IL-13–induced IRAK-M could suppress TLR2 signaling activation (eg, TLR2, hBD2, and IL-8) in human epithelial cells. We found that upregulation of IRAK-M by IL-13 decreased NF-κB p65 levels in nuclei to inhibit transcription of TLR2 and hBD2 genes in human airway epithelial cells. Furthermore, overexpression of IRAK-M in human lung epithelial cells significantly impaired TLR2 agonist–induced NF-κB activation and IL-8 production. It is noted that unlike other IRAKs (eg, IRAK-1 and IRAK-4), IRAK-M does not have significant kinase activity because of the lack of a functional catalytic site in its central ‘‘kinase’’ domain, although it still can downregulate the NF-κB pathway.52,53 Potential mechanisms of IRAK-M–mediated NF-κB inhibition have been described in several studies. Overall, IRAK-M can negatively regulate both canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathway activation depending on the nature of TLR stimuli. For instance, Kobayashi et al22 have shown that IRAK-M can inhibit the NF-κB canonical pathway in a TLR4- and TLR9-dependent manner. IRAK-M has been shown to bind to the MyD88/IRAK-4 complex and thus inhibits IRAK-4–mediated IRAK-1 phosphorylation. This prevents dissociation of IRAK-1 and IRAK-4 from MyD88 and formation of TNF receptor associated factor 6/IRAK-1 complexes, which are critical to the activation of NF-κB p65.52

Excessive immune responses are detrimental to the host. Therefore negative feedback (eg, IRAK-M) is crucial for homeostasis in patients with inflammatory diseases, such as asthma. However, persistent overexpression of airway epithelial IRAK-M resulting from repeated exposures to TH2 cytokines could compromise the innate immunity (eg, TLR2 signaling activation) and impede an effective clearance of pathogens from the airways. In vivo studies, such as murine models, are warranted to dissect the contribution of epithelial IRAK-M to dampened innate immunity in allergic lungs. The role of TH2 cytokine–induced IRAK-M in modulating other TLR pathways, especially in the presence of live bacteria, also needs to be clarified to further our understanding of IRAK-M in suppressing airway defense against bacteria in asthmatic patients.

We realize there are several limitations in our current study. First, because IL-13 has been shown to increase airway epithelial cell proliferation,54–56 it is likely that any changes in mediators, such as IRAK-M, might be related to IL-13–induced airway epithelial phenotypic alteration, including proliferation. Whether IL-13–induced cell proliferation directly affects IRAK-M expression remains unknown and deserves future study. Second, although we showed that IRAK-M regulates TLR2 signaling, such as TLR2 and hBD2, it is likely that IRAK-M might also control other signaling molecules because significant IRAK-M knockdown did not result in the same degree of TLR2 signaling restoration in IL-13–treated airway epithelial cells.

In summary, our data strongly indicate that airway epithelial cell IRAK-M overexpression in TH2 cytokine–exposed airways inhibits epithelial TLR2 signaling activation (eg, TLR2 and hBD2 expression). This might provide a novel mechanism for the increased susceptibility of infections in asthmatic patients. IRAK-M–targeted therapy in the airway epithelium of the lungs of allergic patients might be promising for the prevention, treatment, or both of respiratory tract bacterial infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI070175 and R01 HL088264.

Abbreviations used

- ALI

Air-liquid interface

- AP-1

Activator protein 1

- BEGM

Bronchial epithelial cell growth medium

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- hBD2

Human β-defensin 2

- IRAK-M

IL-1 receptor–associated kinase M

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor κB

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- rhIL-13

Recombinant human IL-13

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: R. J. Martin is a consultant for AstraZeneca and a consultant and speaker for Teva and Merck. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Clinical implications: IRAK-M–targeted therapy in the airway epithelium of the lungs of allergic patients might be promising for the prevention, treatment, or both of respiratory tract bacterial infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130(suppl):4S–12S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sevin CM, Peebles RS., Jr Infections and asthma: new insights into old ideas. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1142–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilette C, Durham SR, Vaerman JP, Sibille Y. Mucosal immunity in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a role for immunoglobulin A? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:125–135. doi: 10.1513/pats.2306032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park GY, Hu N, Wang X, Sadikot RT, Yull FE, Joo M, et al. Conditional regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 in tracheobronchial epithelial cells modulates pulmonary immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:245–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutler B, Hoebe K, Du X, Ulevitch RJ. How we detect microbes and respond to them: the Toll-like receptors and their transducers. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:479–485. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0203082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertz CJ, Wu Q, Porter EM, Zhang YJ, Weismuller KH, Godowski PJ, et al. Activation of Toll-like receptor 2 on human tracheobronchial epithelial cells induces the antimicrobial peptide human beta defensin-2. J Immunol. 2003;171:6820–6826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Q, Martin RJ, Lafasto S, Efaw BJ, Rino JG, Harbeck RJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 down-regulation in established mouse allergic lungs contributes to decreased Mycoplasma clearance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:720–729. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1387OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Q, Jiang D, Minor MN, Martin RJ, Chu HW. In vivo function of airway epithelial TLR2 in host defense against bacterial infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L579–L586. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00336.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elias JA, Lee CG, Zheng T, Ma B, Homer RJ, Zhu Z. New insights into the pathogenesis of asthma. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:291–297. doi: 10.1172/JCI17748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prescott SL. New concepts of cytokines in asthma: is the Th2/Th1 paradigm out the window? J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:575–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomura I, Goleva E, Howell MD, Hamid QA, Ong PY, Hall CF, et al. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis, as compared to psoriasis, skin prevents induction of innate immune response genes. J Immunol. 2003;171:3262–3269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kisich KO, Carspecken CW, Fieve S, Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Defective killing of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis is associated with reduced mobilization of human beta-defensin-3. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramanathan M, Jr, Lee WK, Spannhake EW, Lane AP. Th2 cytokines associated with chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps down-regulate the antimicrobial immune function of human sinonasal epithelial cells. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:115–121. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller T, Terada T, Rosenberg IM, Shibolet O, Podolsky DK. Th2 cytokines down-regulate TLR expression and function in human intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:5805–5814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su J, Xie Q, Wilson I, Li L. Differential regulation and role of interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase-M in innate immunity signaling. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1596–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima K, Hirota T, Obara K, Shimizu M, Jodo A, Kameda M, et al. An association study of asthma and related phenotypes with polymorphisms in negative regulator molecules of the TLR signaling pathway. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:284–291. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes KC, Neely JD, Duffy DL, Freidhoff LR, Breazeale DR, Schou C, et al. Linkage of asthma and total serum IgE concentration to markers on chromosome 12q: evidence from Afro-Caribbean and Caucasian populations. Genomics. 1996;37:41–50. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raby BA, Silverman EK, Lazarus R, Lange C, Kwiatkowski DJ, Weiss ST. Chromosome 12q harbors multiple genetic loci related to asthma and asthma-related phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1973–1979. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balaci L, Spada MC, Olla N, Sole G, Loddo L, Anedda F, et al. IRAK-M is involved in the pathogenesis of early-onset persistent asthma. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1103–1114. doi: 10.1086/518259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wesche H, Gao X, Li X, Kirschning CJ, Stark GR, Cao Z. IRAK-M is a novel member of the Pelle/interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19403–19410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi K, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2002;110:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenzel SE, Trudeau JB, Kaminsky DA, Cohn J, Martin RJ, Westcott JY. Effect of 5-lipoxygenase inhibition on bronchoconstriction and airway inflammation in nocturnal asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:897–905. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Britten KM, Howarth PH, Roche WR. Immunohistochemistry on resin sections: a comparison of resin embedding techniques for small mucosal biopsies. Biotech Histochem. 1993;68:271–280. doi: 10.3109/10520299309105629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu HW, Halliday JL, Martin RJ, Leung DY, Szefler SJ, Wenzel SE. Collagen deposition in large airways may not differentiate severe asthma from milder forms of the disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1936–1944. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9712073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu HW, Trudeau JB, Balzar S, Wenzel SE. Peripheral blood and airway tissue expression of transforming growth factor beta by neutrophils in asthmatic subjects and normal control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1115–1123. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross CA, Bowler RP, Green RM, Weinberger AR, Schnell C, Chu HW. beta2-agonists promote host defense against bacterial infection in primary human bronchial epithelial cells. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen Q, Bai Y, Chang KC, Wang Y, Burris TP, Freedman LP, et al. Liver X receptor-retinoid X receptor (LXR-RXR) heterodimer cistrome reveals coordination of LXR and AP1 signaling in keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14554–14563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.165704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang-Verslues WW, Sladek FM. Nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha1 competes with oncoprotein c-Myc for control of the p21/WAF1 promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:78–90. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Refaeli Y, Field KA, Turner BC, Trumpp A, Bishop JM. The protooncogene MYC can break B cell tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4097–4102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409832102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu HW, Thaikoottathil J, Rino JG, Zhang G, Wu Q, Moss T, et al. Function and regulation of SPLUNC1 protein in Mycoplasma infection and allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:3995–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farghaly HS, Blagbrough IS, Medina-Tato DA, Watson ML. Interleukin 13 increases contractility of murine tracheal smooth muscle by a phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110delta-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1530–1537. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zacharioudaki V, Androulidaki A, Arranz A, Vrentzos G, Margioris AN, Tsatsanis C. Adiponectin promotes endotoxin tolerance in macrophages by inducing IRAK-M expression. J Immunol. 2009;182:6444–6451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen HT, Tsou HK, Hsu CJ, Tsai CH, Kao CH, Fong YC, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 promotes IL-6 production in human synovial fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1219–1227. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hubbard LL, Moore BB. IRAK-M regulation and function in host defense and immune homeostasis. Infect Dis Rep. 2010:2. doi: 10.4081/idr.2010.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oshima N, Ishihara S, Rumi MA, Aziz MM, Mishima Y, Kadota C, et al. A20 is an early responding negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 5 signalling in intestinal epithelial cells during inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;159:185–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Searing DA, Zhang Y, Murphy JR, Hauk PJ, Goleva E, Leung DY. Decreased serum vitamin D levels in children with asthma are associated with increased corticosteroid use. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanak M, Gielicz A, Bochenek G, Kaszuba M, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Szczeklik A. Targeted eicosanoid lipidomics of exhaled breath condensate provide a distinct pattern in the aspirin-intolerant asthma phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1141–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1108. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scotton CJ, Martinez FO, Smelt MJ, Sironi M, Locati M, Mantovani A, et al. Transcriptional profiling reveals complex regulation of the monocyte IL-1 beta system by IL-13. J Immunol. 2005;174:834–845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batra V, Musani AI, Hastie AT, Khurana S, Carpenter KA, Zangrilli JG, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1, TGF-beta2, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 after segmental allergen challenge and their effects on alpha-smooth muscle actin and collagen III synthesis by primary human lung fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atochina-Vasserman EN, Winkler C, Abramova H, Schaumann F, Krug N, Gow AJ, et al. Segmental allergen challenge alters multimeric structure and function of surfactant protein D in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:856–864. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0654OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He YY, Huang JL, Sik RH, Liu J, Waalkes MP, Chignell CF. Expression profiling of human keratinocyte response to ultraviolet A: implications in apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:533–543. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayapal KP, Philp RJ, Kok YJ, Yap MG, Sherman DH, Griffin TJ, et al. Uncovering genes with divergent mRNA-protein dynamics in Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, Martin C, O’Leary JJ, Ruan Q, et al. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Escoll P, del Fresno C, Garcia L, Valles G, Lendinez MJ, Arnalich F, et al. Rapid up-regulation of IRAK-M expression following a second endotoxin challenge in human monocytes and in monocytes isolated from septic patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawai T, Akira S. Signaling to NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dobrovolskaia MA, Medvedev AE, Thomas KE, Cuesta N, Toshchakov V, Ren T, et al. Induction of in vitro reprogramming by Toll-like receptor(TLR)2 and TLR4 agonists in murine macrophages: effects of TLR “homotolerance” versus “heterotolerance” on NF-kappa B signaling pathway components. J Immunol. 2003;170:508–519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birchler T, Seibl R, Buchner K, Loeliger S, Seger R, Hossle JP, et al. Human Toll-like receptor 2 mediates induction of the antimicrobial peptide human beta-defensin 2 in response to bacterial lipoprotein. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3131–3137. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3131::aid-immu3131>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker MN, Diamond G, Verghese MW, Randell SH. CD14-dependent lipopolysaccharide-induced beta-defensin-2 expression in human tracheobronchial epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29731–29736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomita T, Nagase T, Ohga E, Yamaguchi Y, Yoshizumi M, Ouchi Y. Molecular mechanisms underlying human beta-defensin-2 gene expression in a human airway cell line (LC2/ad) Respirology. 2002;7:305–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2002.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Wehkamp K, Wehkamp-von Meissner B, Schlee M, Enders C, et al. NF-kappaB- and AP-1-mediated induction of human beta defensin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917: a novel effect of a probiotic bacterium. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5750–5758. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5750-5758.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Janssens S, Beyaert R. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol Cell. 2003;11:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flannery S, Bowie AG. The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases: critical regulators of innate immune signalling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1981–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Booth BW, Adler KB, Bonner JC, Tournier F, Martin LD. Interleukin-13 induces proliferation of human airway epithelial cells in vitro via a mechanism mediated by transforming growth factor-alpha. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:739–743. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.6.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lankford SM, Macchione M, Crews AL, McKane SA, Akley NJ, Martin LD. Modeling the airway epithelium in allergic asthma: interleukin-13- induced effects in differentiated murine tracheal epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2005;41:217–224. doi: 10.1290/0502012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Booth BW, Sandifer T, Martin EL, Martin LD. IL-13-induced proliferation of airway epithelial cells: mediation by intracellular growth factor mobilization and ADAM17. Respir Res. 2007;8:51. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.