Abstract

Two-component systems (TCS) are short signalling pathways generally occurring in prokaryotes. They frequently regulate prokaryotic stimulus responses and thus are also of interest for engineering in biotechnology and synthetic biology. The aim of this study is to better understand and describe rewiring of TCS while investigating different evolutionary scenarios. Based on large-scale screens of TCS in different organisms, this study gives detailed data, concrete alignments, and structure analysis on three general modification scenarios, where TCS were rewired for new responses and functions: (i) exchanges in the sequence within single TCS domains, (ii) exchange of whole TCS domains; (iii) addition of new components modulating TCS function. As a result, the replacement of stimulus and promotor cassettes to rewire TCS is well defined exploiting the alignments given here. The diverged TCS examples are non-trivial and the design is challenging. Designed connector proteins may also be useful to modify TCS in selected cases.

Keywords: histidine kinase, engineering, promoter, sensor, response regulator, synthetic biology, sequence alignment, connector, Mycoplasma

Introduction

A key mechanism used by bacteria for sensing their environment is based on two-component systems (TCS). These systems typically consist of a sensor protein with a membrane-bound histidine kinase domain (HisKA) and a corresponding regulator protein with a response regulator domain (RR). The sensor protein detects specific changes in the environment and subsequently binds adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This causes a structural change of the sensor protein and, after autophorphorylation at a histidine residue, evokes phosphor-transfer to the corresponding response regulator. The response regulator then changes its structure and mediates a cellular response.1 TCS standard structure is well conserved.2,3 Several databases describe different aspects of TCS.4–7 Mutational analyses of individual components in TCS are described in previous reports.8,9 Design, rewiring, and modifications of TCS have been studied for a long time, including efforts in biotechnology.10–16 Still, it is a major challenge to successfully engineer TCS systems, as direct design attempts only work well for controlled cases and evolutionarily short distances.17 In taking a closer look, it turned out that information for specific cases on individual functional sites and sequences is often lacking. Therefore, we looked closely at evolutionary changes in TCS, in order to create a more solid basis for future design attempts. In synthetic biology, rewiring TCS allows us to construct synthetic networks.18 For this, exchange of TCS promotors, partial or full replacement of sensor and regulator, as well as adding additional components is key.19 The specific motifs involved and the overall topology of the system determine the observed switching behavior.20

Consequently, the aim of this study is to describe and review evolutionary scenarios as a guide to rewire two-component systems.

Taking a large-scale screen on available TCS from various databases as our basis (see Supplementary material), we considered three general scenarios spanning from local to more global changes of TCS: (i) Individual amino acid changes. These lead to direct sequence changes of sensors and regulators, eg, changing specificity of stimulus or allowing the regulation of new genes. (ii) An alternative scenario considers more radical changes such as domain swapping. We performed large-scale screens and identified events in which such exchanges lead to a change in the overall function of a TCS. This can be exploited for more drastic engineering strategies, which are otherwise very difficult to predict in their outcome. (iii) Another modification strategy does not interfere with the sensor or regulator of the TCS. Additional proteins or domains, so called connectors, interact with either one or both of them. This again modulates output and performance of the TCS. Starting from a known event (SafA in Escherichia coli) we consider further proteins, which could have such connector functions and examine their potential to change TCS function.

Results and Discussion

We screened various databases for TCS and their modifications. Supplementary material illustrates this in Table S1 for a screen listing the most frequently occurring contexts in which histidine kinase or response regulator domains were found. Databases we screened include amongst others the database of protein families PFAM,21 the protein database Uniprot,22 as well as further repositories, such as MIST2,4 SENTRA,6 and P2CS.7 Furthermore, there are numerous sensors with periplasmic, membrane-embedded, and cytoplasmic sensor domains and a great diversity of regulator protein contexts.

TCS rewiring by changing residues in sequences

Sequence mutations change sensors and regulators, for instance the specificity of the stimulus recognized or the genes regulated. To gain concrete information useful for engineering, we looked closely at sequences from several bacterial model organisms, focusing especially on the recognition site and the DNA and promotor binding sites. Annotated information on these signatures is often not available and hence relies on detailed manual annotation as well as sequence comparisons. We revalidated predictions by extensive sequence-structure comparisons (more information see Supplementary material).

TCS stimulus signatures

We annotated here several stimulus recognition sites in different model organisms (E. coli 536, E. coli CFT073, E. coli K12 W3110, E. coli O157:H7 EDL933, E. coli K12 MG1655, E coli O157:H7 Sakai pO157, E. coli UTI89, Salmonella, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella pneumophila, Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and for different stimuli (Table 1A; phosphor, iron, copper, osmotic, stress, citrate, fumarate and nitrate/nitrite;23–25 sequence, genome and domain analysis, see Materials and methods). Table 1A shows the best consensus derived. However, for concrete engineering experiments and detection in new genomes, the signatures themselves are important and are given in detail summarizing all investigated sequences. They can be used directly for engineering. Detailed alignments are given in Supplementary material, section 1.2.

Table 1A.

Stimulus recognition consensus sequences for various TCS stimuli.

| Stimulus | No. of sequences | Position | Recognition sequence1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphor | 1 | 29–32 | GYLP |

| Osmotic | 4 | 36–158 | NFAILPSLQQFNKVLAYEVRMLMTDKLQLEDGTQLVVPPAFRREIyrelgISLYTNEA AEEAGLRWAQHYEFLSHQMAQQLGGPTEVRVEVNKSSPVVWLKTWLSPNIWVRVPLTE IHQGDFS |

| Stress | 6 | 25–135 | LVYKFTAERAGRQSLDDLMNSSLYLMRSELREIPPHDWGKTLKEmdlnlsfdlrvepls kyhlddismhrlrggeivALDDQYTFIQRIPRSHYVLAVGPVPYLYYLHQMr |

| Iron | 6 | 35–64 | HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNNDRHIMREIRE |

| Copper | 3 | 37–86 | HSVKVHFAEQDINDLKEISATLERVLNHPDETQARRLMTLEDIVSGYSNVLISLADSH GKTVYHSPGAPDIREFARDAIPDKDARGGEVFLLSGPTMMMPGHGHGHMEHSNWRMISL PVGPLVDGKPIYTLYIALSIDFHLHYINDLMNK |

| Citrate | 4 | 43–182 | asfedyltlhvrdmamnqakiiasndsvisavktrdykrlatianklQRDTDFDYVVIG DRHSIRLYHPNPEKIGYPMQFTKPGALEKGESYFITGKGSMGMAMRAKTPIFDDDGKV IGVVSIGYLVSKIDSWRAEFLLP |

| Fumarate | 4 | 42–181 | SQISDMTRDGLANKALAVARTLADSPEIRQGLQKKPQESGIQAIAEAVRKRNDLLFIVV TDMHSLRYSHPEAQRIGQPFKGDDILKALNGEENVAINRGFLAQALRVFTPIYDENHIS KAQIGVVAIGLELSRVtqqindsrw |

| Nitrate/Nitrite | 8 | 38–151 | sslrDAHAINKAGSLRMQSYRLGYDLPSGEPDKNAHRQMFQQAlhspvltnlnvwyv peavkTRYAHRNANWDGMNNRLQGGDDPWYNENIPNYMNQQDRFTLALDHY Qerkqffec |

Notes:

Only the consensus recognition sequences are listed according to Uniprot. Well annotated sensors and organisms were compared as listed in Supplementary material. The sensor protein recognition site composition depends on the signal and is independent of the organism. Exact sequences and positions are aligned in Supplementary material. Accurate numbering according to E. coli proteins can be transferred to other organisms. Conserved amino-acids are labeled in bold print. Less conserved amino-acids are labeled in lowercase.

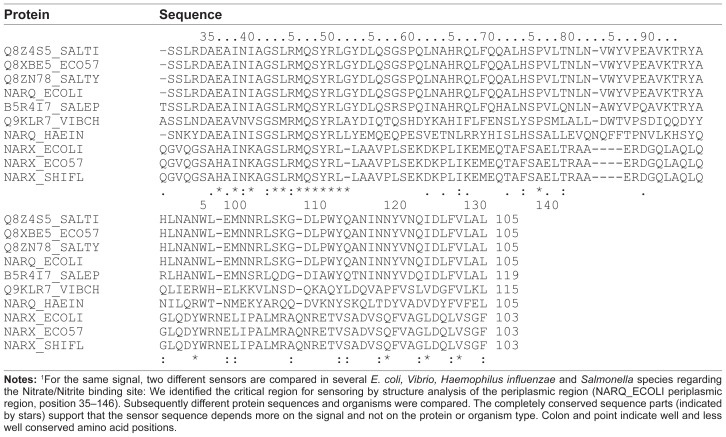

For rewiring, the transfer of such consensus sequences should be possible between organisms and proteins with the same sensor. To test in how far this is possible, we compared in detail the nitrate/nitrite recognition site (nitrate/nitrite sensor proteins NarX and NarQ; Table 1B). For different sensor proteins in the above-analyzed organisms, the structure of the sensor is accurately known (NarX or NarQ). We compared these sensor sequences in several E. coli, Salmonella, Vibrio and Haemophilus influenzae strains. The critical sensory region identified by sequence analysis was comparable in spite of the two different organisms and different proteins (for NARQ_ECOLI periplasmic region: position 35–146; numbering according to the E. coli Uniprot sequences). This supports the hypothesis that the signal is much more important than the organism or even the TCS family. In general, the recognition sites seem to depend strongly on the signal type, but remain conserved across the tested species.

Table 1B.

Alignment of the Nitrate/Nitrite recognition site comparing NarX and NarQ.1

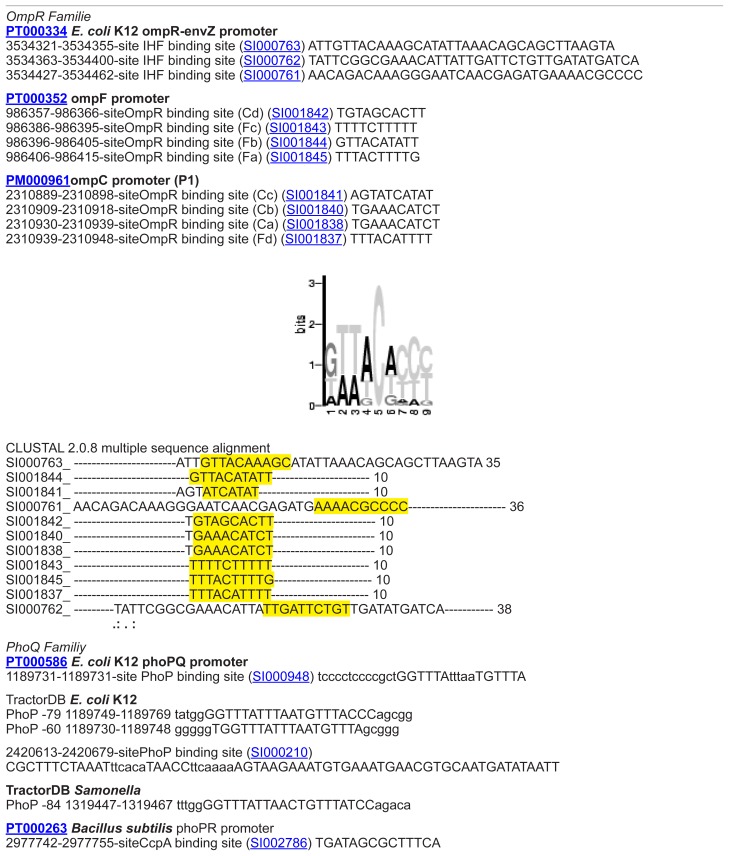

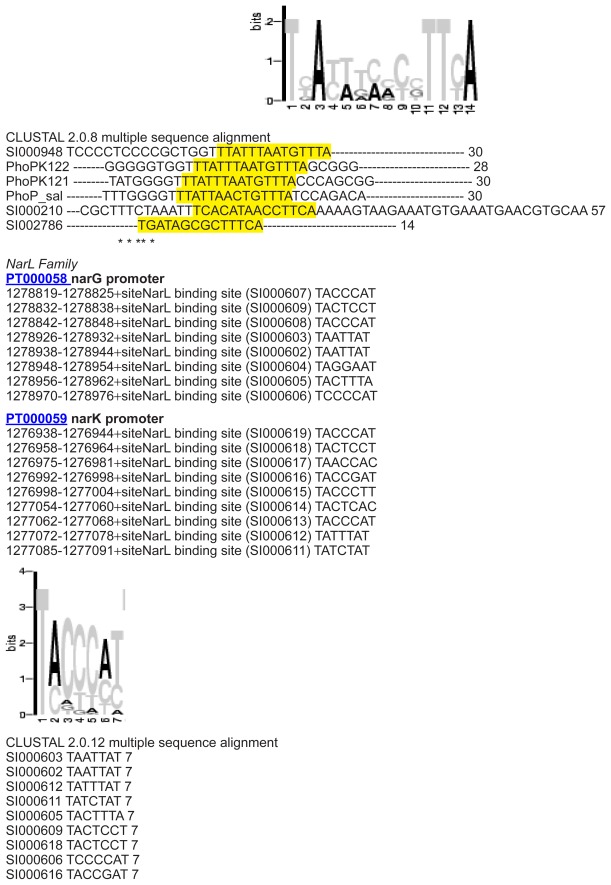

Binding sites on the DNA

Another way to modify TCS functionality is to exchange the cellular response. Therefore, we analyzed the DNA binding site between regulator protein and DNA. Promotor information is normally badly annotated. The required promotor data retrieval in this study was achieved in a manual, hand curated manner by direct sequence comparison. DNA binding sites for target genes in E. coli K-12 were first collected from different sources (Prodoric,26 DBTBS,27 TractorDB,28 and PDBSum) and afterwards analyzed applying specific perl-scripts and regarding further E. coli strains (E. coli 536, E. coli CFT073, E. coli K-12 W3110, E. coli O157:H7 EDL933, E. coli K-12 MG1655, E. coli O157:H7 Sakai pO157, E. coli UTI89). Conserved motifs for the DNA binding sites were summarized in form of consensus sequences per TCS family (E. coli, Table 2A; other gram-negative bacteria, Table 2B). Re-annotation using databases and subsequent sequence analysis tools are described in Materials and methods.

Table 2A.

Specific target gene DNA sequences in E. coli.1

| Regulated gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| OmpC | TTTACATTTTGAAACATCT |

| OmpF | T[GT][GT][TG]TA[CG][AC][TA][AC]TTT[TC] |

| OmpF/OmpC | TTT[TA]C-TTTT[TG] |

| NarG1 | 1 TACCCATTAA 10 |

| NarG2 | 1 TAACCAT--- 7 |

| NarG3 | 1 TAATTAT--- 7 |

| NarG4 | 1 TACTTTA--- 7 |

| NarG5 | 1 -AGGGGTA-- 7 |

| NarG6 | 1 TAGGAAT--- 7 |

| NarG7 | TTTAACCCGAtcggggtatg |

| NarK | TAC[TC][CG][CA]T |

| CitB | agtAATTTAATTaatt |

| LytT | [TA][AC][CA]GTTN[AG][TG] |

| LytT | taaggAAATAAAACTGATTTTcacgtca |

| AlgR | aaatGAATATTTATTCAAat |

| GlnG/GlnK | tgcaCCACCATGGTGCA |

| Spo1 | 1 ------------TTTGTCGAATGTAA----------- 14 |

| Spo2 | 1 --AATTTCATTTTTAGTCGAAAAACAGAGAAAAACAT 35 |

| Spo3 | 1 AAAAGAAGATTTTTCGACAAATTCA------------ 25 |

Notes:

Profiles of target gene binding sites bound by regulators in E. coli are given. Consensus sequences were derived from detailed multiple alignments (see Supplementary material) mining several databases (Prodoric, TractorDB, PDB and PDBSum, PubMed). Sequences and positions were aligned (Supplementary material). Given binding sequences were first found in E. coli K-12 strains and were verified for the other E. coli strains (see Supplementary material) using motif specific scripts (Materials and methods). Less conserved parts are labeled in lowercase letters, motifs with brackets and strongly conserved parts are highlighted by black boxes.

Table 2B.

Specific target gene DNA sequences in further gram negative bacteria.1

| Family | Regulated gene | Function | Example organism | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NtrC | GlnH | Transcription factor | Salmonella | GacatTTGCACTTAAATAGTGCACaaccc |

| NtrC | GlnA | Transcription factor | Salmonella | ttctaTTGCACCAATGTGGTGCTTaatgt cattgAAGCACTATTTTGGTGCAAcatag |

| NtrC | GlnK | Transcription factor | Salmonella | CcattATGCACCGTCGTGGTGCGTttttc |

| NtrC | GlnA | Transcription factor | Salmonella | CtataATGCACTAAAATGGTGCAAccttt |

| NarL | NarK | Transcription factor | Salmonella | AatagCCTACTCATTAAGGGTAATaacta |

| NtrC | GlnG | Transcription factor | Shigella flexneri | CtataATGCACTAAAATGGTGCAAcctgt |

| ArgR | ArgA | Transcription factor | Salmonella | actaaTTTCGAATAATAATTCACTAgtggg |

| ArgR | ArgC | Transcription factor | Salmonella | cgttaATGAATAAAAATACATaatta |

Notes:

The table shows TCS target gene promotor sites in Salmonella (two strains) and Shigella. Capital letters indicate similarities within the binding site between the three compared organisms.

In most cases the promotor nucleotide sequences identified were quite short. As analyzed previously for different promoter sequences,29,30 we found that the TCS promoter sequences we identified have to occur in multiple copies to allow for higher specificity (including different affinities and different functions). Motifs were often repeated allowing oligomeric binding of the regulator protein.

Based on our analyses, it was possible to retrieve the concrete numbers of replicates and distances between the replicates: Table 3 summarizes the regulator proteins, the regulated genes, the numbers of binding site replicates, and the distances between the replicates.

Table 3.

Promotor binding sites.

| Response regulator protein | Regulated gene | Repetition | Distance [NS] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citrate utilization protein B (CitB) | Citrate lyase (CitC) | 6 | 40 |

| Nitrogen regulation protein (NtrC) | Sequences glutamine synthetase (GlnA) | 2 | 63 |

| Nitrogen regulation protein (NtrC) | Nitrogen regulator protein (GlnK) | 7–12 | Variable |

| Nitrate/Nitrite response regulator protein (NarL) | Respiratory nitrate reductase (NarG) | Variable | Ca. 6 |

| Nitrate/Nitrite response regulator protein (NarL) | Nitrite extrusion protein (NarK) | Variable | Variable |

| Osmolarity response regulator (OmpR) | Outer membrane protein C and F (OmpC/OmpF) | 3 | 7 |

As these results show that the stimulus recognition sites and promoter regions are well conserved, we are confident that the resulting consensus sequences given in Tables 1–3 will be of great help in direct design experiments17 (see also Supplementary material, Figure S2 and Table S2 for detailed suggestions on HisKA substitution design).

TCS rewiring by domain shuffling and diverged domains

The screens furthermore revealed more extensive changes in TCS, such as domain swapping. We identified diverged regulators or sensors in a genome where only one partner is known (Legionella, Listeria) and spot strongly diverged TCS by conserved domains in a new context (several examples including M. pneumoniae).

Diverged TCS domains

Extensive sequence analysis per TCS family, including related organisms, enabled us to better describe and predict the regulatory function for three TCSs in L. pneumophilia. New partners could be found for the osmosis-sensing family (OmpR) and the nitrate/nitrite response family (NarL). Table 4A contains the predicted and previously missing partners, the identification methods, and the TCS functions. Regarding the organism L. monocytogenes, three new TCSs within the NarL and the OmpR family could be identified, see Table 4B.

Table 4.

Recognition of divergent TCS and missing TCS partners.

| Family | Identification | Stimulus | Sensor2 | Regulator2 | Strain | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A)L. pneumophila str. Philadelphia1 | ||||||

| OmpR | Iterative sequence searches with cut off e-30 using OmpR sequences from Enterobacter cloacae | Mg starvation | QseC GI:52841522 Known/annotated by PMID 15448271 |

GI:52841523 which is potential similar to QseB | Philadelphia 1 | Regulated protein FliC; GI: 52841570; Flagella regulation; |

| NarL | Iterative sequence searches with cut off e-30 using NP_288375 E. coli O157:H7 str. EDL933 | Carbon | BarA GI: 52842130 Known/annotated by PMID 15448271 |

GI:52842852 which is potential similar to UvrY | Philadelphia 1 | Regulated protein CsrA; GI:52841018 Carbon storage regulator |

| NarL | Iterative sequence searches with cut off e-30 in E. coli ETEC H10407 | Pheromone | GI:52840952 which is potential similar to EvgA | Philadelphia 1 | Regulated protein EmrY; GI:52841684; antibiotic resistance | |

| Family | Identification | Stimulus | Sensor* | Regulator* | Strain | Function |

| (B)Listeria monocytogenes3 | ||||||

| NarL | Iterative sequence searches with cut off e-30 in E. coli ETEC H10407 | Q4EKW8_LISMO which is potential similar to EvgS | GI: 16804553 which is potential similar to EvgA | EGD-e | Antibiotic resistance | |

| OmpR | Iterative sequence searches with cut off e-30 in B. subtilis; the sequences of these proteins where used to search in the Listeria genome | Stress | GI: 16804620 GI: 16803101 which is potential similar to CSSS_BACSU |

GI: 16804621 which is potential similar to CSSR_BACSU | EGD-e | Regulated protein HtrA; serine protease |

| OmpR | PSI-Blast search in B. subtilis with cut off e-60; the sequences of these sensors where used to search in the Listeria genome | Mg starvation | GI: 16803061 which is potential similar to ZP_03239257 | PhoP GI: 16804539 Known/annotated by PMID 11679669 |

EGD-e | Virulence, antimicrobial peptide resistance |

Notes:

New annotated features (interactions or part of TCS) apparent from sequence searches with various available TCS sequences and domains in the genome sequence (Genbank acc. No.: AE017354, Chien M, et al, 2004). Regulated proteins are given as well as homologous standard TCS. Predicted changes (mainly by their operon context) in their function for L. pneumophila are indicated on the right. The right-most column summarizes which aspect of the TCS is reported here new.

Listed are well characterized homologs from other organisms which have the same function within the same family.

Table contains additional features (interactions or parts of TCS) extending what is already known in KEGG or annotated in Genbank (Acc. No.: AE017262) or Listilist (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/ListiList/). On the left the TCS family is given. Starting from B. subtilis TCS sequences we searched for missing sensor and regulator proteins. The right-most column summarizes which aspect of the TCS is reported here new.

Some of the identified proteins are already known to be involved in TCS, but their connection to a specific family is unknown. The now identified TCS partners are critical for the functioning of these TCS in Legionella and Listeria. They justify further analysis and confirmation by direct experiments.

Extensive TCS domain shuffling

Further divergence may lead to the appearance of typical TCS domains in a new context. To detect such domain shuffling events, we applied PROSITE predictions, further sequence analyses, and literature mining. All examples investigated scrutinized proteins with either a HisKA domain or a RR domain, focusing on rather diverged cases. Four prokaryotic and even three eukaryotic examples are shown with far diverged proteins including new functional properties (Table 5). Two biotechnologically interesting examples are described in more detail:

Table 5.

Natural examples for domain shuffling in divergent TCS.1

| Domain | Protein | Context | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| HisKin | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase | Glucose metabolism In S. cerevisiae | Inhibits the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by phosphorylation of the E1 alpha subunit, thus contributing to the regulation of glucose metabolism |

| HisKin | Adenylate cyclase | Sporulation in some organisms | Stringent response, protein kinases are activated (PKAs) |

| HisKin | BCKD-kinase | Valine, leucine and isoleucine catabolic pathways in Mouse | Catalyzes the phosphorylation and inactivation of the branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex, the key regulatory enzyme of the valine, leucine and isoleucine catabolic pathways. Key enzyme that regulate the activity state of the BCKD complex |

| HisKin | Phytochrome A | Regulatory photoreceptor In Deinococcus | Regulatory photoreceptor which exists in two forms that are reversibly interconvertible by light: the Pr form that absorbs maximally in the red region of the spectrum and the Pfr form that absorbs maximally in the far-red region. Photoconversion of Pr to Pfr induces an array of morphogenic responses, whereas reconversion of Pfr to Pr cancels the induction of those responses. Pfr controls the expression of a number of nuclear genes including those encoding the small subunit of ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase, chlorophyll A/B binding protein, protochlorophyllide reductase, rRNA, etc. It also controls the expression of its own gene(s) in a negative feedback fashion |

| Response Reg | Adventurous-gliding motility protein Z | Chemosensory system in Myxococcus | Required for adventurous-gliding motility, in response to environmental signals sensed by the frz chemosensory system. Forms ordered clusters that span the cell length and that remain stationary relative to the surface across which the cells move, serving as anchor points that allow the bacterium to move forward. Clusters disassemble at the lagging cell pol |

| Response Reg | Adenylate cyclase | Sporulation in some organisms | Stringent response, response regulators are activated |

| Response Reg | Serine/threonine-protein kinase ppk18 | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Serine/threonine-protein kinase ppk18 plays pivotal roles in cell proliferation and cell growth in response to nutrient status |

Notes:

The table shows natural domain shuffling events where sensor domains and response regulator domains appear in different new contexts. In the three prokaryotic as well as in the eukaryotic examples only domains can be recognized but new functions are adopted.

Shuffled sensor domain: The branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex (BCKD) in mice was considered as a quite diverged example.31 BCKD possesses a characteristic nucleotide-binding domain and a four-helix bundle domain similar to a TCS sensor. Binding of ATP induced disorder to ordered transitions in a loop region at the nucleotide-binding site. These structural changes led to the formation of a quadruple aromatic stack in the interface between the nucleotide-binding domain and the four-helix bundle domain, finally resulting in a movement of the top portion of two helices and to a modified enzyme activity. Our analysis indicates a diverged TCS with HisKA domain but without an RR domain and with new cellular response, namely to change enzymatic activities. Until now only the structural similarity to the Bergerat fold family has been demonstrated by inhibition experiments using radicicol as an autophosphorylation inhibitor for histidine kinases32 but there is no in vivo evidence of BCKDHK in a signaling event of a two-component histidine kinase. In contrast, two component systems in plants such as maize seem to be genome-wide spread33 (see Supplementary material, Table S3).

Shuffled regulator domain: If further signaling is mediated by transcription, the trans-activation domain involves a wide-range of different DNA binding motifs. Such domains appear also in new enzyme contexts or activities. One identified eukaryotic example for natural domain shuffling of a RR domain in a new protein context was the predicted serine/threonine protein kinase ppk18 in the “fission yeast” Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Ppk18 plays pivotal roles in cell proliferation and cell growth in response to nutrient status.34 A RR domain is located C-terminal in the protein (well conserved PROSITE signature PS50110) and is target of rapamycin (TOR). TOR itself activates ppk18 by phosphorylation but does not contain the typical HisKA domain. Consequently eukaryotes can have similar operational interactions as typical prokaryotic TCS, in particular in yeast and in plants. Our computational analysis of this protein function according to the available data suggests a rather similar operation according to its interactions, in particular by its involvement of a RR domain (see Supplementary material Table S4).

High divergence is easily achieved by new molecular partners of the domain that is known from prokaryotic TCS, as shown in these eukaryotic examples. Nevertheless, there is a certain level of convergent evolution observable in the examples, regarding their regulatory function and effect.

A putative new family of TCS in Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Modification in TCS can even go so far that both TCS partners are quite diverged and it is difficult to identify them as TCS. Combining bioinformatical sequence and structure analyses, there is a chance to identify such (quite) degenerated TCS in prokaryotes. A putative new TCS family encoded in the M. pneumoniae genome, so far described as TCS-free, is suggested here. In particular, MPN013 and MPN014 could form a rather diverged sensor and regulator pair in M. pneumoniae.

a. Putative Sensor: These proteins could not be identified with simple sequence searches, since direct sequence similarity searches did not yield significant hits.35 After at least seven PSI-BLAST iterations, the collected alignment included described TCS sensors in addition to the UPF family to which MPN013 was previously known to belong to, the non-annotated protein family DUF16 exclusively found in Mycoplasma.

To verify MPN013 as a potential sensor protein structure, analysis with respect to the primary, secondary and tertiary structure and several alignments were established:

A re-check of the prediction via PSI-BLAST analysis identified M. pneumoniae protein MPN013 as a potential sensor protein; its primary structure sequence was similar to NarX in Psychrobacter arcticum (PSI-BLAST e-value 6 × 10−13 after 5 iterations).

Afterwards we analyzed the secondary and tertiary structure of MPN013. The homology model applying SWISS-MODEL yielded the template 2ba2A (crystal structure of MPN010, another member of the DUF16 family) for MPN013. 2ba2A is a four alpha helix-bundle corresponding to the HisKA domain of a sensor protein. The MPN013 sequence extended the C-terminus and contained an additional second domain.

MPN013 starts as all sensor proteins with an unspecified domain (1–120) probably representing a signal-perception domain. Following this, we found an alpha-helical structure (130–165). This outcome was supported by secondary structure prediction (PredictProtein36 and Predator37) and was in line with the homology model. The last part was a mixture composed of helices, sheets, and loops. Secondary structure predictions were not completely identical. However, secondary structure alignments with the software SSEA38 showed a similarity to alpha/beta sandwiches (z-score 2.28; normalized score of 54.5).

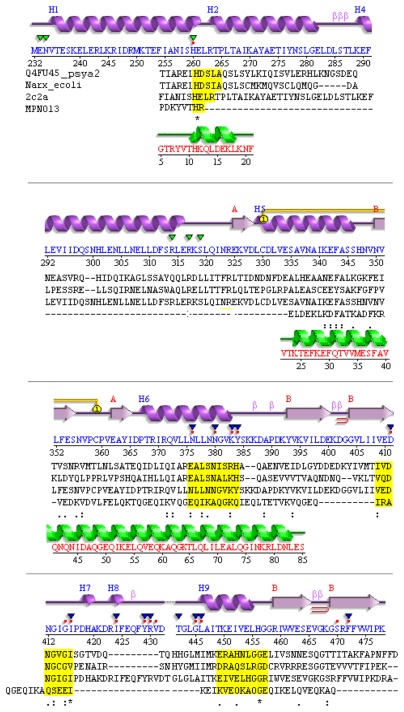

To further verify the features required for a TCS, it is demonstrated that MPN013 can be aligned in primary and secondary structure with NarX from Psychrobacter arcticus (Fig. 1). The corresponding E. coli NarX sensor was added for comparison purposes. The structure (Fig. 1; top panel) was given according to the structure template 2c2a (HisKA853 of Thermotoga maritima) from PDB, which should be valid for NarX as well as HisKA in general. Conserved residues for TCS are highlighted (yellow boxes) and the homology model for MPN013 (PDB entry 2ba2_A for MPN010) is shown in green.

Figure 1.

Divergent TCS sensor in M. pneumoniae.

Notes: Compared are the structure template (T. maritima), structure of NarX from E. coli, P. arcticus, and MPN013 (M. pneumoniae). Aligned are the secondary structure from PDB template 2c2a_A (top, magenta; HK853 from T. maritima) and its sequence (blue), valid (sequences aligned) for NarX from P. arcticus and the sequence of MPN013. Conserved residues are highlighted by yellow boxes. Below the secondary structure triangles indicate binding sites annotated in PDBSum (green: ADP binding site, blue SO4 binding site, red dots ligand binding site). Conserved residues for TCS (see above) are highlighted in yellow boxes. Structure: Calculated secondary structure (green) according to the SWISS-MODEL template for MPN013 (PDB entry 2ba2_A for MPN010).

Four conserved amino acid boxes were analyzed next: The first box (Fig. 1, yellow) represents the strongly conserved histidine environment, which binds phosphor for the transfer to the RR. This site is situated in the four-helix bundle. The comparison between the E. coli, P. arcticus and MPN013 sequences already made clear that this site was variable with respect to its position and environment. The secondary structure comparison revealed that the histidine has to be situated at the end of an alpha helix. However, the further environment of the histidine residue in MPN013 is diverged. A second box could mainly be found in E. coli and was therefore rarely conserved. The third and fourth conserved boxes comprise the ATP-binding site (Fig. 1). Those two sites are more highly conserved, as demonstrated by the conserved PFAM based pattern Glu/Asn-X-Ile/Leu-X-Asn/Ala-X and Asp/Glu-X-Gly/Ser-X-Gly/Glu-Ile. This secondary structure comparison showed that the structure might be even more flexible than initially assumed.

Furthermore, regarding a tentative ATPase activity predicted by the sequence analysis, close comparisons with the HisKA subclasses as described by Grebe3 showed that the MPN013 histidine environment was new (see Supplementary material). It was clearly different than what has been already described; however, the closest relative was a mixture of the HK3b and HK11 environment. An autophosphorylation region was identified and contained the conserved amino acids histidine and arginine just as in the HPK11 family. Within the ATP binding site, the MPN13 motif contained the conserved glycine as observed in the HK3b motif.

Consequently, even when the overall structure of the putative sensor did not match perfectly, conservation was apparent in structure as well as with respect to key residues. However, other parts of the sequence vary more than standard TCS, which explains why this was not detected by sequence comparison before. Furthermore, though key conserved structure and sequence features point to a diverged TCS in M. pneumoniae, its divergence may lead also to diverged function (see examples above).

b. Putative Response Regulator: Additional predictive evidence for this diverged TCS became available by searching for a corresponding regulator protein:

This search was initiated by an organism specific iterative BLAST with NarL from P. arcticus. NarL is the corresponding RR to the HisKA of NarX in P. arcticus, which was the most similar HisKA to MPN013. Consequently, on a primary structure level, NarL is similar to the Mycoplasma protein MPN014. This result was further supported by gene neighborhood considerations,39,40 which are also expected for TCS as sensors and regulator genes are often situated directly next to each other in different genomes.41

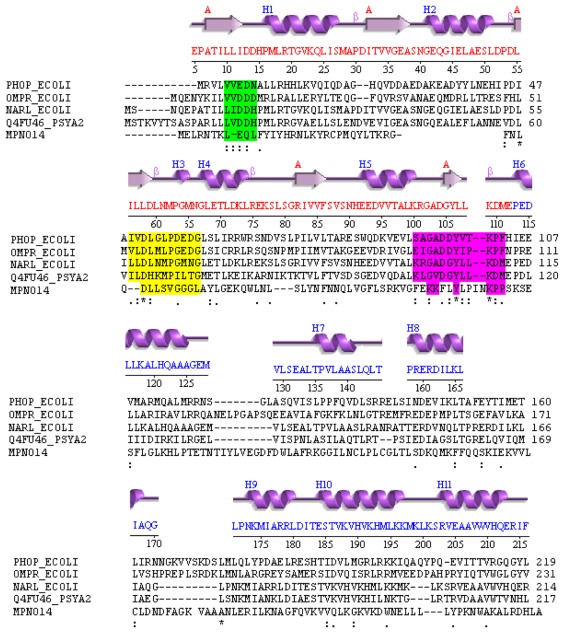

In order to test this hypothesis on a secondary structure level, a homology model for MPN014 was calculated. MPN014 was not only located next to MPN013, but the secondary structure sequence alignment showed that it was homologous to NarL from P. arcticus and the general structure template 1p2f (TM_0126 of T. maritima) for RR in TCS. It has already been noted that MPN014 contains a topoisomerase/primase domain (“toprim” domain) including a nucleotidyl transferase or hydrolase function according to PFAM.42

For a detailed structure sequence comparison the secondary structure is provided (according to the PDB file: 1rnl) and the sequence of NarL in E. coli. A comparison between the MPN014 sequence and NarL in P. arcticus is shown in Figure 2. The sequence comparison displayed good similarity between NarL in P. arcticus, NarL in E. coli and MPN014 in M. pneumoniae (conserved residues are highlighted).

Figure 2.

Diverged TCS regulator in M. pneumoniae.

Notes: Compared are the structure template (T. maritima), structure of PhoP, OmpR and NarL from E. coli, NarL in P. arcticus and MPN014 (M. pneumoniae). Aligned are the secondary structure from PDB template 1rnl (top, magenta; NarL from T. maritime; red letters: phosphor binding three-layer alpha/beta sandwich, blue: DNA-binding alpha orthogonal bundle) and its sequence (red), valid (sequences aligned) for PhoP, OmpR and NarL from E. coli, NarL in P. arcticus and MPN014 (M. pneumoniae). Conserved residues are highlighted in colored boxes. The first green highlighted part corresponds to the first part of the regulator overview. Conserved area starts with an aliphatic residue, followed by a charged residue. The second conserved part (yellow background) starts with an aliphatic residues and a Leu, followed by a charged residue and some Gly. The third part (dark red background) contains a strongly conserved lysine, followed by hydrophobic residues. N-terminal of the conserved lysine two positively charged residues is found. Secondary structure predictions (Predator, PredictProtein) predict a mixed structure out of helices, sheets and many loops over the whole protein. Consequently the phosphor binding part could be an alpha/beta sandwich like in other regulators. The second part of MPN014 contains no helix-turn-helix motif, but is predicted to be involved in DNA binding due to high sequence similarity to DNA primase/topoisomerase.

The phosphor binding alpha/beta 3-layer sandwich was apparent (red letters in the NarL sequence) as well as the DNA-binding alpha-orthogonal bundle (blue letters). The alignment was good enough to enable identification of all conserved regions (colored boxes). The second part of MPN014 did not display an HTH motif, but the similarity of MPN014 to the topoisomerase/primase domain and its particular relatedness to DNA-primase related proteins (protein cluster CLSK542094) supported the idea that the topoisomerase/primase domain may bind to DNA (just) as many regulators in TCS do.

Based on the patterns, which were only partially conserved, it became apparent that this element was probably a quite diverged RR. (i) The sequence contained only weak hydrophobic residues in the region corresponding to beta-strand-1. (ii) Immediately following, it contained the conserved pair of acidic residues involved in binding the metal ion for phosphorylation reactions, it was the combination glutamic acid plus glutamine as second amino acid. (iii) Hydrophobic residues corresponding to beta-strand- 3 and the immediately following absolutely conserved aspartic acid that is the site of phosphorylation were observed, as well as some hydrophobic residues corresponding to beta-strand-4, but the sequence did not contain the immediately following and highly conserved serine/threonine that binds to the phosphoryl group and mediates conformational change. This was replaced by an asparagine.

Nevertheless, based on the above results, we see that structure and sequence features are sufficiently conserved to suggest that the pair MPN013/MPN014 could be a rather diverged TCS. Furthermore, its diverged functionality is at least used by M. pneumoniae (expression data see below).

The entire DUF16 family is M. pneumoniae specific, but contains a number of potential sensor proteins (MPN139, MPN138, MPN137, MPN130, MPN127, MPN104, MPN038, MPN013, MPN010, MPN655, MPN524, MPN504, MPN501, MPN410, MPN368, MPN344, MPN287, MPN283, MPN204), and the encoded two M. pneumoniae proteins related to the DNA-primase family could act as potential regulator proteins (MPN014, MPN353). In M. genitalium we have only identified a homologous counterpart for the regulator. However, the multiple copies found are another indicator that the protein family is at least useful and kept in M. pneumoniae (and this although in general there is genome reduction in parasite genomes). This is further confirmed by EST expression data for MPN013 and preliminary expression data for MPN014 (see http://coot.embl.de/Annot/MP/).

Rather diverged TCSs do thus occur in various and quite different instances. They are involved in changing of partners, but also in changing of different residues, cooperative changes can even lead to the adoption of new functions. This is difficult to design. For such experiments, complex, correlated changes in the overall protein structure and function revealed eg, by statistical coupling analysis43 have to be taken into account. This method has been shown to work well for the redesign of proteins such as Hsp70 and of allosteric changes.44 A key requirement is a sufficient statistical sampling, ie, large alignments to study sequence variation in the protein family of interest. Furthermore, extensive structural information is required.45 Combining both aspects allows defining specific and important regions within the protein where mutations influence each other. However, for large protein families these regions predict quite well coordinated or cooperative changes in proteins.43 This can then be exploited for protein design, for instance the design of protein chimeras while preserving functionality of critical domains.46 We are confident that this approach will also work for two-component system design and maybe even in a diverged TCS. At least a sufficient number of TCS sequences, required to get the statistical power for reliable predictions, are available as well as known structures to define structural sectors of conserved and cooperatively changing regions in two-component systems for sensor and regulator proteins.

TCS rewiring by additional components

TCS can furthermore be modified by additional components, so-called connectors. These modify or enhance signal transmission, increase the binding to regulator proteins, or act as additional response modifying proteins within a TCS.47,48 Such interacting proteins enhance evolution and adaptation of TCS further and are also an interesting option to modify their rewiring. In general, the connector is present in addition to the sensor and regulator protein.

a. Connector family SafA, Sensor-associating factor A: Eguchi et al describe the SafA as a small membrane protein in connection with TCS, to be found in the EvgS/EvgA and PhoQ/PhoP TCS in E. coli.48 The expression of EmrY is induced by activated EvgA. The activated EvgS/EvgA system activates the PhoQ sensor protein of the PhoQ/PhoP. SafA thus supports the interaction between the two TCS.

With the help of organism specific alignments, sequence and gene context analysis, it could be confirmed that SafA does not only occur in E. coli but also in Shigella and Salmonella. All identified potential SafA proteins are unknown or hypothetical proteins and STRING predicts interactions to either EvgS or proteins with similar functions (see Table 6A and Supplementary material, Table S5).

Table 6A.

SafA containing proteins (potential connector proteins).

| Protein | Description | Organism | STRING score |

|---|---|---|---|

| NP_310132 | Hypothetical protein ECs2105 | E. coli 0157 | 0,9 to EvgS |

| ZP_02799272 | Conserved hypothetical protein | E. coli 0157 | 0,9 to EvgS |

| YP_540723 | Hypothetical protein C1714 | E. coli UTI89 | 0,9 to EvgS |

| NP_837211 | Hypothetical protein S1655 | S. flexneri | 0,76 to EvgS |

| NP_458304 | Putative phosphodiesterase | S. typhi | 0,65 to ygiM (put. signal transduction protein) |

| NP_462516 | Putative phosphodiesterase | S. typhimurium | 0,6l to lon |

Notes:

SafA similar proteins can be found in several organisms. This table lists the proteins of the family, a short description and the detected organism as well as the predicted probability to interact with TCS as a connector according to the protein interaction database STRING.

b. EAL and GGDEF domains: EAL domains have diguanylate phosphodiesterase activity and are found in diverse bacterial signaling proteins.49,50 If they interact with a TCS, they may influence it. This is documented for GGDEF domain containing regulators in many prokaryotic signal connected proteins, as the GGDEF domain has an enzymatic activity for synthesis of the second messenger molecule cyclic-di-GMP.51 We looked for new examples applying gene context methods, literature mining, and the STRING database.39 Table 6B displays the predicted interaction partners for several proteins containing an EAL-domain. Indeed, EAL proteins were often predicted to interact with known regulator proteins or had partners with DNA-binding domains (as most of the known RR in TCS). Alternatively they interacted with proteins containing the GGDEF domain. EAL and GGDEF domains can frequently be found in response regulator domain containing proteins.

Table 6B.

Putative connector proteins containing an EAL-domain and their interaction partners.

| Protein with EAL-Domain | Interaction partner1 |

|---|---|

| >Q21G90_SACD2 Diguanylate cyclase/phosphodiesterase Saccharophagus degradans (full protein with two domains) |

Sde_3649 GGDEF family protein Sde_2537 hypothetical protein Sde_3232 hypothetical protein Sde_3313 putative diguanylate phosphodiesterase Sde_1079 putative diguanylate phosphodiesterase Sde_3648 Formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycolase Sde_0078 GGDEF domain protein Sde_3427 Putative diguanylate cyclase (GGDEF) Sde_3693 res_reg receiver domain protein (CheY-like) Sde_1063 GGDEF family protein |

| >A6Q1G4_NITSB Signal transduction response regulator nitratiruptor sp. |

dgkA Diacylglycerol kinase NIS_0211 Putative uncharacterized protein dnaG DNA primase DnaG NIS_0567 Putative uncharacterized protein NIS_0004 Putative uncharacterized protein NIS_1647 Putative uncharacterized protein NIS_1732 Putative uncharacterized protein NIS_0150 Putative uncharacterized protein NIS_0136 Putative uncharacterized protein |

| >A1AD34_ECOK1 Putative uncharacterized protein rtn E. coli O1 |

yedQ hypothetical protein yaiC Putative uncharacterized protein ydeH Putative uncharacterized protein ydeH yeaP Putative uncharacterized protein yeaP ycdT predicted diguanylate cyclase yfiN Putative diguanylate cyclase yneF Putative uncharacterized protein yneF yeaI Putative uncharacterized protein yeaI yejA Putative uncharacterized protein yejA yejB Predicted oligopeptide transporter subunit |

Note:

Interaction predictions included sequence- and structure analysis and data from public interaction databases such as STRING database.

For protein engineering or synthetic biology experiments, connectors could be used to specifically modify TCS or connect two TCS. The analyzed examples are known and shown to work in several organisms, but the connector may also be tried on TCS from other species by just over-expressing these together. Evolution uses a large pool of potential interacting proteins.52,53 The same connectors are used only on comparatively short distances: In prokaryotes in particular, there is a counter selection, as wrong interactions lead to wrong regulation. However, as in eukaryotic evolution, where new protein interactions compensate for random drift in functional complexes,54 new protein design may of course adapt connectors for broader use. For instance, the SafA connector protein family efficiently bridges two different TCS systems. This can be attractive for new designs in synthetic biology such as synthetic circuits.55

TCS can also occur in eukaryotes such as plants, for instance in maize56 and in Arabidopsis, where systems showing activities similar to TCS are found.57,81 These could in principle be quite diverged eukaryotic TCS, similar to the Mycoplasma example, or fairly close to standard TCS. Supplementary material, Table S6 shows both is true to some extent. Thus, in maize 25 proteins similar to HisKA proteins could be found, but only 20 of them are known to be involved in a plant TCS; for Arabidopsis the ratio is such that from 61 proteins similar to HisKA proteins there are only 16 proteins known and annotated to be participating in a TCS. For response regulators the differences between identified domains and annotated response regulators are even larger, indicating more divergence. However, this analysis also shows that a considerable number of these TCS are surprisingly well conserved in their domain architecture, and sometimes even in their motifs and signatures. At least these comparatively conserved eukaryotic TCS can be tackled with the strategies and bioinformatics data given here based largely on prokaryotic data. For more diverged eukaryotic TCS again careful and complex calculations as outlined above are the only potential strategy. However, the number of eukaryotic TCS sequences available is comparatively low and hence the statistical power of sequence-structure correlation algorithms will not be strong.

The various examples and three modification strategies applied also raise the question about a quantitative estimate of TCS divergence in general. To answer this question we first give an overview and a sequence tree on the species distribution of HisKa and response regulator domains in general (see Supplementary material, Figure S1). Furthermore, we made a detailed quantitative assessment of TCS divergence regarding the HisKA site (see Supplementary material, Figure S2) and performed various analyses about the different context in which TCS domains can occur. Those analyses included the frequency of different domain-family occurrences as well as specific domain combinations (Supplementary material Table S1 gives a detailed example). However, to get a more general overview, we give in Table S6 also an estimate on the occurrence of key TCS domains versus the number of annotated and known TCS in several bacterial genomes plus the recent data on maize as well as Arabidopsis plant genomes. As the data show, the number of domains is in all cases clearly higher than the number of annotated TCS. These new domain contexts for key marker domains of TCS give an upper bound on the number of highly diverged TCS for these different species, in reality the actual figure is lower (depending on how strict the function of the TCS as a sensor plus phosphorelay system is defined).

Conclusions

The plasticity of TCS is of high interest. It has been studied since a long time and documented in various databases.4–6 The aim of this study is to identify evolutionary modification scenarios and analyze their use for engineering TCS. Extensive genome comparisons, sequence, and structure analysis of natural instances revealed three general rewiring scenarios modifying TCS: (i) exchanges of few amino acid residues or (ii) of whole domains,54 as well as (iii) applying connector proteins.47,48,50 For engineering, the accurate and specific binding sites, promoter motifs, and stimulus recognition motifs described should work best. In contrast, the identified diverged TCS, including potential eukaryotic variations, partners for Listeria and Legionella TCS, and a highly diverged TCS family in Mycoplasma show that extensive changes in TCS function are possible, but involve complex cooperative changes, which are not easily predicted or designed. Of the connectors analyzed, the SafA family may be attractive for synthetic circuit design,55 as they efficiently bridge TCS systems.

Materials and Methods

The identification and analysis of individual TCS components was performed in separate steps and with specific methods for sequence alignment, for the investigation of domain and structural features, for their gene context, as well as for pathway aspects.

Methods for sequence analysis

Large-scale screens for diverged TCS were conducted on different databases (PFAM,21 the protein database Uniprot22) and we examined further repositories such as MIST2,4 SENTRA6 and P2CS.7 Furthermore, KEGG58 databases as well as specific sequence searches were used to collect all known and available TCS in standard model organisms. Iterative sequence searches and domain analyses were conducted as described previously.40 We included the following model organism and strains: E. coli genome sequences E. coli 536,59 E. coli CFT073,60 E. coli K-12 W3110,61 E. coli O157:H7 EDL933,62 E. coli K-12 MG1655,63 E. coli O157:H7 Sakai,64 E. coli UTI8965 as well as Shigella 2a str. 2457T and Salmonella typhi strains CT1866/Ty267 ATCC 700931; S. typhimurium LT2,68 B. subtilis (strain 168), S. aureus (COL),69 L. pneumophila (Philadelphia 1),70 L. monocytogenes (EGD-e71/F236572) and M. pneumoniae (M129)73 as well as all sequences and organisms available from PFAM. Data on promotor interactions were retrieved from the ProDoric database,26 which comprises information from exhaustive literature analyses, computational sequence predictions, and DBTBS,27 a reference database of published transcriptional regulation events on B. subtilis. This source of information was complemented by studies performed in TractorDB,28 which contains a collection of computationally predicted transcription factor binding sites in gamma-proteobacterial genomes.

Domains were tested and verified by comparison with known domain families, including data from databases such as SMART,74 PFAM,21 and Uniprot.22 TCS components of various genomes were extensively compared in their sequence composition, intrinsic properties, as well as regarding amino acid conservation and variation.

To calculate consensus sequences, the COnsensus Biasing By Locally Embedding Residues method was applied (COBBLER).75 A single sequence was selected from a set of blocks and enriched by replacing the conserved regions with consensus residues derived from the blocks. Comprehensive tests demonstrated that these embedded consensus residues improved performance in readily available sequence query searching programs. Further sequence analysis programs included BLAST,35 position-specific BLAST (PSI-BLAST), and ClustalW.76 The visualization of sequence conservation was achieved by using sequence logos, which show the degree of amino acid conservation by different letter sizes or uppercase and lowercase letters.

The DNA binding sites in related genomes were identified with perl-scripts, which employ the Fuzznuc program of the EMBOSS package77 as a method for pattern searching. A binding site was assigned as soon as it matched the pattern. Screening runs allowing mismatches were also conducted and results were manually annotated, eg, whether the pattern was long enough to tolerate mismatches or whether symmetry-breaking mismatches were not tolerated. The described approach enabled the identification of conserved binding sites with mismatches in related E. coli genomes starting from E. coli strain K-12.

Methods for structural analysis

Based on results from PFAM and SMART, a search for essential functional domains in TCS was initiated. Moreover, an analysis of their cellular location within the cell using annotation from literature and public databases was performed.

To determine domain boundaries, we included functional and structural information. The transfer of domain features to non-annotated proteins was achieved with the help of search patterns (according to PROSITE and PFAM patterns).

After domain analyses individual domain results were assembled to a complete protein structure. Tertiary and secondary structure information was added from PDBSum, AnDOM, SCOP78 and CATH.79 Homology models were created using SWISS-MODEL.80 Further analyses included secondary structure, binding features as well as function-specific motifs and key conserved structural residues. The structure of TCS was furthermore analyzed in more detail starting from available PDB structures.81 We started with well-annotated domains in sensor and regulator proteins and compared these to less well-characterized sequences. Furthermore, detected structural or sequential characteristics in all analyzed proteins were transferred to proteins without annotations.

Structure predictions were performed by PredictProtein,36 and Predator.37 Secondary structure alignments were derived with the Server for Protein Secondary Structure Alignment (SSEA).38 Predictions for protein interactions exploited the STRING tool,39 structure analyses, and literature mining.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary material contains sequence data and alignments as well as the analysed HisKA families.

Modification by domain swapping

General flexibility of TCS

The examples listed below were found in various database searches and screens. Table 1 illustrates this for a screen in PFAM database listing the most often occurring contexts in which sensor or response regulator domains can be found.

Note, however, that the flexibility of TCS is far higher. Besides PFAM database we screened NRDB, but considered also other repositories such as MIST2,1 SENTRA2,3 and P2CS.4 From these and other sources (eg, there are numerous sensors with periplasmic, membrane-embedded and cytoplasmic sensor domains5–8 and a great diversity of receiver domain contexts9–11 we investigated the full potential for rewiring TCS.

Overall, there are numerous sensors with periplasmic, membrane-embedded and cytoplasmic sensor domains5–8 and a great diversity of receiver domain contexts.10,11

TCS stimuli

The sensor periplasmatic area sequence for specific stimuli is nearly identical in different organisms. This is shown here for the periplasmatic sensor binding sites (numbering according to the corresponding Swiss-Prot entry) as well as for different stimuli. This compilation as well as the promotor compilation (1.3) used information of specific strains (E. coli 536, E. coli CFT073, E. coli K12 W3110, E. coli O157:H7 EDL933, E. coli K12 MG1655, E. coli O157:H7 Sakai pO157, E. coli UTI89, Salmonella, B. subtilis, S. aureus, Legionella pneumophila, Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae) including sequence and structure of sensors and receivers, promotor binding site and conservation of key features. These further data complement the information given in the results section of the paper.

| Phosphor | ||

|

>PHOR_ECOLI 29-32 (4) GYLP |

||

| Osmotic | ||

|

>ENVZ_ECOLI 36-158 (123) NFAILPSLQQFNKVLAYEVR MLMTDKLQLEDGTQLVVPP AFRREIYRELGISLYSNEAAE EAGLRWAQHYEFLSHQMAQQ LGGPTEVRVEVNKSSPVVWLK TWLSPNIWVRVPLTEIHQGDFS |

>ENVZ_SALTY 36-158 (123) NFAILPSLQQFNKVLAYEVR MLMTDKLQLEDGTQLVVPP AFRREIYRELGISLYTNEAAE EAGLRWAQHYEFLSHQMAQQ LGGPTEVRVEVNKSSPVVWLK TWLSPNIWVRVPLTEIHQGDFS |

>Q02EG5_PSEAB 15-117 TLWLVLIVVLFSKALTLVYLLMN EDVIVDRQYSHGAALTIRAFWAA DEESRAAIAKASGLRWVPSSAD QPGEQHWPYTEIFQRQMQMELG PDTETRLRIHQPS |

|

>ENVZ_SALTI 36-158 (123) NFAILPSLQQFNKVLAYEVR MLMTDKLQLEDGTQLVVPP AFRREIYRELGISLYTNEAAE EAGLRWAQHYEFLSHQMAQ QLGGPTEVRVEVNKSSPVVW LKTWLSPNIWVRVPLTEIHQ GDFS |

>ENVZ_SHIFL 36-158 (123) NFAILPSLQQFNKVLAYEVR MLMTDKLQLEDGTQLVVPP AFRREIYRELGISLYSNEAAE EAGLRWAQHYEFLSHQMA QQLGGPTEVRVEVNKSSPVV WLKTWLSPNIWVRVPLTEIH QGDFS |

|

| Stress | ||

|

>RSTB_ECOLI 25-135 (111) LVYKFTAERAGKQSLDDLM NSSLYLMRSELREIPPHDWG KTLKEMDLNLSFDLRVEPLS KYHLDDISMHRLRGGEIVAL DDQYTFLQRIPRSHYVLAVG PVPYLYYLHQMR |

>B3AUE7 _ECO57 25-135 (111) LVYKFTAERAGKQSLDDLM NSSLYLMRSELREIPPHDWG KTLKEMDLNLSFDLRVEPLS KYHLDDISMHRLRGGEIVAL DDQYTFLQRIPRSHYVLAVG PVPYLYYLHQMR |

>Q8ZPL6_SALTY 25-135 (111) LVYKFTAERAGRQSLDDLMKSS LYLMRSELREIPPREWGKTLKEM DLNLSFDLRVEPLNHYKLDAATT QRLREGDIVALDDQYTFIQRIPRS HYVLAVGPVPYLYFLHQMR |

|

>Q8XED5_ECO57 25-135 (111) LVYKFTAERAGKQSLDDLM NSSLYLMRSELREIPPHDWG KTLKEMDLNLSFDLRVEPLS KYHLDDISMHRLRGGEIVAL DDQYTFLQRIPRSHYVLAVG PVPYLYYLHQMR |

>Q8Z6R8_SALTI 25-135 (111) LVYKFTAERAGRQSLDDLM KSSLYLMRSELREIPPREWG KTLKEMDLNLSFDLRVEPL NHYKLDAATTQRLREGDIVA LDDQYTFIQRIPRSHYVLAV GPVPYLYFLHQMR |

>Q83KZ3_SHIFL 25-135 (111) LVYKFTAERAGRQSLDDLMKSS LYLMRSELREIPPREWGKTLKEM DLNLSFDLRVEPLNHYKLDAATT QRLREGDIVALDDQYTFIQRIPRS HYVLAVGPVPYLYFLHQMR |

| Iron | ||

|

>BASS_ECOLI 35-64 (30) HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNN DRHIMREIRE |

>BASS_SALTY 35-64 (30) HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNN DRHIMREIRE |

>Q8FAU6_ECOL6 38-67 (30) HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNNDR HIMREIRE |

|

>B2NQU4_ECO57 38-67 (30) HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNN DRHIMREIRE |

>Q83PA1_SHIFL 38-67 (30) HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNN DRHIMREIRE |

>Q8Z1P5_SALTI 38-67 (30) HESTEQIQLFEQALRDNRNNDR HIMREIRE |

| Copper | ||

|

>CUSS_ECOLI 37-86 (150) HSVKVHFAEQDINDLKEISA TLERVLNHPDETQARRLMT LEDIVSGYSNVLISLADSQGK TVYHSPGAPDIREFTRDAIPD KDAQGGEVYLLSGPT MMMPGHGHGHMEHSN WRMINLPVGPLVDGKPI YTLYIALSIDFHLHYIND LMNK |

>CUSS_ECO57 37-86 (150) HSVKVHFAEQDINDLKEISAT LERVLNHPDETQARRLMTL EDIVSGYSNVLISLADSHGK TVYHSPGAPDIREFARDAIPD KDARGGEVFLLSGPTMMMP GHGHGHMEHSNWRMISLP VGPLVDGKPIYTLYIALSIDF HLHYINDLMNK |

>CUSS_ECOL6 37-86 (150) HSVKVHFAEQDINDLKEISATLE RVLNHPDETQARRLMTLEDIVS GYSNVLISLADSHG KTVYHSPGAPDIREFARDAIP DKDARGGEVFLLSGPTMMM PGHGHGHMEHSNWRMISLP VGPLVDGKPIYTLYIALSIDF HLHYINDLMNK |

| Citrate | ||

|

>DPIB_ECOLI 43-182 (140) ASFEDYLTLHVRDMAMNQA KIIASNDSVISAVKTRDYKRL ATIANKLQRDTDFDYVVIGD RHSIRLYHPNPEKIGYPMQFT KQGALEKGESYFITGKGSM GMAMRAKTPIFDDDGKVIG VVSIGYLVSKIDSWRAEFLLP |

>Q8XBS0_ECO57 43-182 (140) ASFEDYLTLHVRDMAMNQA KIIASNDSVISEVKTRDYKRL ATIANKLQRDTDFDYVVIGD RHSIRLYHPNPEKIGYPMQFT KQGALEKGESYFITGKGSMG MAMRAKTPIFDDDGKVIGV VSIGYLVSKIDSWRAEFLLP |

>Q8Z8I7_SALTI 43-182 (140) ASFEDYLASHVRDMAMNQA KIIASNDSIIAAVKNRDYKRL AIIANKLQRGTDFDYVVIGD RHSIRLYHPNPEKIGYPMQFT KPGALERGESYFITGKGSIGM AMRAKTPIFDNEGNVIGVVS IGYLVSKIDSWRLDFLLP |

|

>Q8FJZ9_ECOL6 63-202 (140) ASFEDYLTLHVRDMAMNQA KIIASNDSIISAVKTRDYKRL ATIADKLQRDTDFDYVVIGD RHSIRLYHPNPEKIGYPMQFT KPGALEKGESYFITGKGSIGM AMRAKTPIFDDDGKVIGVVS IGYLVSKIDSWRAEFLLP |

||

| Fumarate | ||

|

>Ecoli_dcsu 42-181 (140) SQISDMTRDGLANKALAVAR TLADSPEIRQGLQKKPQESGI QAIAEAVRKRNDLLFIVVTD MQSLRYSHPEAQRIGQPFKG DDILKALNGEENVAINRGFL AQALRVFTPIYDENHKQIGV VAIGLELSRVTQQINDSRW |

>DCUS_ECOL6 42-181 (140) SQISDMTRDGLANKALAVA RTLADSPEIRQGLQKKPQES GIQAIAEAVRKRNDLLFIVVT DMHSLRYSHPEAQRIGQPFK GDDILKALNGEENVAINRGF LAQALRVFTPIYDENHKQIG VVAIGLELSRVTQQINDSRW |

>DCUS_SHIFL 42-181 (140) SQISDMTRDGLANKALAVAR TLADSPEIRQGLQKKPQESGI QAIAEAVRKRNDLLFIVVTD MHSLRYSHPEAQRIGQPFKG DDILKALNGEENVAINRGFL AQALRVFTPIYDENHKQIGV VAIGLELSRVTQQINDSRW |

|

>DCUS_ECO57 42-181 (140) SQISDMTRDGLANKALAVAR TLADSPEIRQGLQKKPQESGI QAIAEAVRKRNDLLFIVVTD MQSLRYSHPEAQRIGQPFKG DDILKALNGEENVAINRGFL AQALRVFTPIYDENHKQIGV VAIGLELSRVTQQINDSRW |

||

| Nitrate/Nitrite | ||

|

>NARX_ECOLI 38-151 (114) QGVQGSAHAINKAGSLRMQ SYRLLAAVPLSEKDKPLIKE MEQTAFSAELTRAAERDGQ LAQLQGLQDYWRNELIPAL MRAQNRETVSADVSQFVAG LDQLVSGFDRTTEMRIET |

>NARQ_ECOLI 35-146 (112) SSLRDAEAINIAGSLRMQSY RLGYDLQSGSPQLNAHRQL FQQALHSPVLTNLNVWYVP EAVKTRYAHLNANWLEMN NRLSKGDLPWYQANINNYV NQIDLFVLALQHYAERK |

>Q8Z4S5_SALTI 35-146 (112) SSLRDAEAINIAGSLRMQSYRLG YDLQSGSPQLNAHRQLFQQALH SPVLTNLNVWYVPEAVKTRYAH LNANWLEMNNRLSKGDLPWYQ ANINNYVNQIDLFVLALQHYAE RK |

|

>NARX_ECO57 38-151 (114) QGVQGSAHAINKAGSLRMQ SYRLLAAVPLSEKDKPLIKE MEQTAFSAELTRAAERDGQL AQLQGLQDYWRNELIPALM RAQNRETVSADVSQFVAGL DQLVSGFDRTTEMRIET |

Q8FF85_ECOL6 40-151 (112) SSLRDAEAINIAGSLRMQSY RLGYDLQSGSPQLNAHRQL FQQALHSPVLTNLNVWYVP EAVKTRYAHLNANWLEMN NRLSKGDLPWYQANINNYV NQIDLFVLALQHYAERK |

>Q8ZN78_SALTY 35-146 (112) SSLRDAEAINIAGSLRMQSYRLG YDLQSGSPQLNAHRQLFQQALH SPVLTNLNVWYVPEAVKTRYAH LNANWLEMNNRLSKGDLPWYQ ANINNYVNQIDLFVLALQHYAER |

|

>NARX_SHIFL 38-151 (114) QGVQGSAHAINKAGSLRMQ SYRLLAAVPLSEKDKPLIKE MEQTAFSAELTRAAERDGQL AQLQGLQDYWRNELIPALM RAQNRETVSADVSQFVAGL DQLVSGFDRTTEMRIET |

>Q8XBE5_ECO57 35-146 (112) SSLRDAEAINIAGSLRMQSY RLGYDLQSGSPQLNAHRQL FQQALHSPVLTNLNVWYVP EAVKTRYAHLNANWLEMNN RLSKGDLPWYQANINNYVN QIDLFVLALQHYAERK |

|

DNA-binding sites

The promotor sites of two-component systems upstream of the receiver or the sensor gene are very specific (unique in the genome) but very short. The receiver protein binds to the promoter region of the regulated gene. Additionally, it regulates the expression of its sensor and frequently the expression of itself. Sometimes all the parts are even regulated by only one promotor region.

In the following section we compared the annotated promoter sequences of the organisms E. coli K12, Salmonella typhimurium, and B. subtilis.

The binding sequence for one protein family within different organisms and between sensor promotor and promoter of the regulated gene are found to be conserved.

Hyphens are used to mark variable nucleotides.

The yellow labelled sequences show the short but conserved core binding sites within the promotor region.

The glutamine example can be found in the manuscript, other examples are listed here.

Modification by Diverged Systems

Domain shuffling in HisKA

We searched for HisKa domains in non two-component systems (sequence composition, Prosite motifs). The found examples are probably independent proteins and functions from two-component systems.

>PDK_YEAST 126-386 Pyruvate dehydrogenase

Inhibits the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by phosphorylation of the E1 alpha subunit, thus contributing to the regulation of glucose metabolism.

AYPYELHNPPKIQAKFTELLDdhedaivvlakglq eiQSCYPKFQISQFLNFHLKERITM KLLVTHYLSLMAQNKGdtnkrMIGILHRDLPIAQL IKHVSDYVNDICFvkfnTQRTPVLI HPPSQDITFTCIPPILEYIMTEVFKNAFEAQIAL gkeHMPIEINLLKPdDDELYLRIRDH GGGITPEVEALMFNYSYSTHTQQSAdsestdlpge qinnvSGMGFGLPMCKTYLELFGGK IDVQSLLGWGTDVYIKLKGPS

>CYAD_DICDI 654-928 Adenylate cyclase

Through the production of cAMP, activates cAMPdependent protein kinases (PKAs), triggering terminal differential and the production of spores.

-------------------------------- ------------------LDYILPELLK NAMRATMEShldtpynVPDVVITIANNDIDLIIRI SDRGGGIAHKDLDRVMDYHFTTAEA STQdprinplfghldmhsggqsgpmHGFGFGLPTS RAYAEYLGGSLQLQSLQGIGTDVYL RLRHID

>BCKD_MOUSE 159-404 BCKD-kinase (PMID: 11562470)

Catalyzes the phosphorylation and inactivation of the branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex, the key regulatory enzyme of the valine, leucine and isoleucine catabolic pathways. Key enzyme that regulate the activity state of the BCKD complex.

BCKD features a characteristic nucleotide-binding domain and a four-helix bundle domain. Binding of ATP induces disorder-order transitions in a loop region at the nucleotide-binding site. These structural changes lead to the formation of a quadruple aromatic stack in the interface between the nucleotide-binding domain and the four-helix bundle domain, where they induce a movement of the top portion of two helices.

----------------------------------- --------------LDYILPELLK NAMRATMEShldtpynVPDVVITIANNDIDLIIRI SDRGGGIAHKDLDRVMDYHFTTAEA STQdprinplfghldmhsggqsgpmHGFGFGLPTS RAYAEYLGGSLQLQSLQGIGTDVYL RLRHID

>PHYA_POPTM 901-1117 (217)

Phytochrome A

Regulatory photoreceptor which exists in two forms that are reversibly interconvertible by light: the Pr form that absorbs maximally in the red region of the spectrum and the Pfr form that absorbs maximally in the far-red region. Photoconversion of Pr to Pfr induces an array of morphogenic responses, whereas reconversion of Pfr to Pr cancels the induction of those responses. Pfr controls the expression of a number of nuclear genes including those encoding the small subunit of ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase, chlorophyll A/B binding protein, protochloro-phyllide reductase, rRNA, etc. It also controls the expression of its own gene(s) in a negative feedback fashion.

YLKKQIWNPLSGIIFSGKMMEGTELGAEQKELLHT SAQC-QCQLSKILDD-SDLDSIIEG YLDLEMVEFTLREYYGCYQSSHDEKH-EKGIPIIN DALKMAETLYGDSIRLQQVLADFCR CQLILTPSG-GLLTVSASFFqrpvgailfilVHSGK LRIRHLGAGIPEALVDQMYGE--- ---DTGASVEGISLVISRKLVKLMNGDVRYMREAG K-SSFIISVELAG

HisKa substitution

One way to modify TCS is to change one HisKa domain into another HisKa domain. To verify this possibility a substitution matrix for HisKa exchange experiments was calculated with the Phylip algorithm including sequences from different strains of E. coli, S. typhimurum, B. subtilis and S. aureus (Fig. 1 with detailed coloring). The established and introduced substitution matrix allows calculating diverged domain swapping experiments and eases the HisKA substitution which may be more challenging than the experiments reported. As a result from the substitution matrix it can be concluded that the distances between families are far more challenging and higher and consequently the chance of success for engineering experiments becomes lower.

Domain shuffling in regulator

We searched for response regulator domains occurring in non two-component systems (sequence composition, prosite motifs). The found examples are not well annotated proteins. Consequently a connection to two-component systems can not be definitely excluded but it is unlikely due to additional manual literature searches for the protein’s function.

AGLZ_MYXXD 4-422 (15342587) Adventurous-gliding motility protein Z

Required for adventurous-gliding motility, in response to environmental signals sensed by the frz chemosensory system. Forms ordered clusters that span the cell length and that remain stationary relative to the surface across which the cells move, serving as anchor points that allow the bacterium to move forward. Clusters disassemble at the lagging cell pol.

RVLIVESEHDFALSMATVLKGAGYQTALAETAADA QRELEKRRPDLVVLRAELKDQSGFV LCGNIKkgkwGQNLKVLLLSSESGVDGLAQHRQTP QAADGYLAIPFEMGELAALSHGIV

CYAD_DICDI 954-1076 (18832717)

Adenylate cyclase

Through the production of cAMP, activates cAMPdependent protein kinases (PKAs), triggering terminal differential and the production of spores.

SVLVIDDNPYARDSVGFIFSSVFNSaiVKSANSSV EGVRDLKYAIatdsnFKLLLVDYHM PGCDGIEAIQMIVdNPAFSDIKIILMILPSDSFAH MNEKTKNITTLIKPVTPTNLFNAIS KTF

PPK18_SCHPO 1198-1279 (18855897) Serine/ threonine-protein kinase ppk18

The cytoplasmic serine/threonine kinases transduce extracellular signals into regulatory events that impact cellular responses. The induction of one kinase triggers the activation of several downstream kinases, leading to the regulation of transcription factors to affect gene function.

KALICVSKLNLFSELIKLLKSYKFQVSIVTDEDKM LRTLMADEkFSIIFLQLDLTRVSGV SILKIVRssnCANRNTPAIALT------------- ------------------------

A putative new family of TCS in mycoplasma pneumoniae

The following HisKA alignment examines the potential Mycoplasma pneumopilia histidine kinase domain in comparison with the domain classes of Grebe12 and Hakenbeck.13 A new HisKA profile for Mycoplasma pneumopilia histidine kinase is added, labeled in red. Capital letters show conserved amino acids, lower case letter show amino acid groups (t = tiny; s = small; p = polar; c = charged; + = positive; r = aromatic; h = hydrophobic; a = aliphatic).

Strongly conserved amino acids are highlighted in yellow.

HPK 1a . . SH-L+TPL . . h -----X-Box-----------D . . h . . hh . NLh HPK 1b . MSH-h+TPL S X-Box HPK 2a . DhAH-L+TPh . . h X-Box HPK 2b hSH-hRTPL . Rh HPK 2c . . h . H-hK . Ph . . h HPK 3a hTHSLKTPh . hL HPK 3b DhSHEL+NPh . . h HPK 3c . . h . H-hK . Ph . . h HPK 3d . hSHDL . QPL . . h HPK 3e AAAAHELGTPL X-Box HPK 3f h . H-L . . . h . . h HPK 3g AHELNNPh . . h HPK 3h hSHDh . . PL . . h HPK 3i WhH . hKTP HPK 4 . hAHEh . . Ph . . h X-Box HPK 5 LR . . . HE . . N no P X-Box HPK 6 RHDhhN noP HPK 7 hHD noP HPK 8 . . . PHFLyN no P HPK 9 . AH(S/T) KG no P H E HPK 10 F+HDY . N (no P) HPK 11 EhHHRh+NNLQ (noP) New_HPK H + no X-Box Q4FU45_PSYA2 --- TIARELHDSLAQSLSYLKIQISVLERHLKNGSDEQNEASV--RQHIDQIKAGL SSAY 55 NARX_ECOLI ---TIARELHDSIAQSLSCMKMQVSCLQMQG----DALPESS--- RELLSQIRNELNASW 50 2c2a FIANISHELRTPLTAIKAYAETIYNSLGELDLSTLKEFLEVIIDQSNHLENLLNELL 60 Y013_MYCPN DFSPDKYVTHR------------------------------------------------- * : HPK 1a D . . . h . . hh . HPK 1b HPK 2a D . . hh . . hh . HPK 2b h . . hh . HPK 2c h . . hh . HPK 3a Dh . . hh . HPK 3b h . . hh . HPK 3c h hh HPK 3d h hh HPK 3e + hh . . h . HPK 3f h hh HPK 3g D . . . h . . hh HPK 3h D . . . h . . hh HPK 3i KWL . Fhh . Qhh HPK 4 D . . . h . Qhhh HPK 5 hh . hhG HPK 6 AB h . . hh- HPK 7 . h . . hh . HPK 8 h . hP . h . hQ HPK 9 HPK 10 hh . h R h HPK 11 ThhPh . hhh New_HPK T pa Q4FU45_PSYA2 QQLRDLLITFRLTIDNDNFDEALHEAANEFALKGKFEITVSNRVMTLNLSATEQIDLIQI AR 117 NARX_ECOLI AQLRELLTTFRLQLTEPGLRPALEASCEEYSAKFGFPVKLDYQLPPRLVPSHQAIHLLQI AR 112 2c2a RLERKSLQINREKVDLCDLVESAVNAIKEFASSHNVNVLFESNVPCPVEAYIDPTRIRQVLL 122 Y013_MYCPN ---------------------ELDEKLKDFATKADFKR-VEDKVDVLFELQKTQGEQIKVQG 48 : : : : . . . . . : : : HPK 1a . NLh . NAh+ys h . h . h . D . G . Gh HPK 1b h . h . h . DsG . Gh h HPK 2a . NLh . NAh+ys h . h . h . D . G . G HPK 2b . NLh . NA . Ry h . h . h . D . G . Ghs E HPK 2c . NL . . NAh . y h . h . h . B . G . Gh HPK 3a NLh . NAh+y h . h . h . D . G . Gh HPK 3b NLh . NA . . y h . h . h . DNG . Gh HPK 3c . NL . . NAh . y h . h . h . B . G . Gh HPK 3d . NLh . NAh+yT h . h . h . DTG . Gh HPK 3e NLh . NAVDyA h . h . h . DDG . G . . HPK 3f . NLh . NAh . y h . h . h . D . G . Gh h . HPK 3g NLh . NAhKF h . h . h . D . G . Gh h HPK 3h NLh . NAhKF h . h . h . D . G . Gh HPK 3i . NALKYS T . h . h . D . G . Gh HPK 4 NLh . NAhzhh h . h . h . D . G . Gh h HPK 5 NLh-NAh . h h . h . h . D . G . Gh h HPK 6 NLh . NAh . HG h . h . h . D . G . GhP HPK 7 EAh . NAh+Hs h . h . h . D . G . Gh HPK 8 . hhENAh . y h . h . h . D . G . Gh HPK 9 hh . . h . . PhhHhhRN ADHG hhh . h . DDG . Gh HPK 10 . . hh . NAhE HPK 11 . ELhsNAh+ys h . h . h New_HPK p aps p a pG a Q4FU45_PSYA2 EALSNISRHA--QAENVEIDLGYDDEDKYIVMTIVDNGVGISGTVDQ--------- TQ 164 NARX_ECOLI EALSNALKHS--QASEVVVTVAQNDNQ--VKLTVQDNGCGVPENAIR---------SN 157 2c2a NLLNNGVKYSKKDAPDKYVKVILDEKDGGVLIIVEDNGIGIPDHAKDRIFEQFYRVDT 180 Y013_MYCPN EQIKAQGKQIEQLTETVKVQGEQ----------IRAQGEQIKAQSEE----------- 85 : : . : : : : :* : HPK 1a G . GLGLshh . hh . . HGG . h . h HPK 1b G . GLGLshh . . hh . . MGG h h HPK 2a G . GLGLshh . . hh . . HGG h . h HPK 2b G . GLGLshh . . hh . . HGG . h . h HPK 2c GLGLshh . . hh G . h . h HPK 3a G . GLGLshh . . hh . Y . G . h . h HPK 3b G GLGLsh . . . hh . HGG HPK 3c G GLGLshh . . hh G . h . h HPK 3d GhGLGLshh . . hh . . hGG . h . h . S . . HPK 3e GhGLGL LLERsGA . h . F . N HPK 3f GhGLGL hhE . HGG . h . h HPK 3g GTGhGLshh . +hh . . HGG HPK 3h GTGhGLshh . +hh . . HGG HPK 3i GhGLyLh . . h . . . h . . . h . h . S HPK 4 GhGL . hh . . hh . HGG . h . h . HPK 5 GhGL . hh . . . h GG . h . h HPK 6 G . GLGLyhh+ . hh yGG . h . h HPK 7 GL . Gh . -+h . . hGG . h . h HPK 8 h . h HPK 9 GRGhG hDVV+ HPK 10 G . GLGL HPK 11 shGL G New_HPK + p G s Q4FU45_PSYA2 HHGLMIMKERAHNLGGELIVSNNESQGTTITAKFAPNFFD 204 NARX_ECOLI HYGMIIMRDRAQSLRGDCRVRR RESGGTEVVVTFIPEK-- 195 2c2a GLGLAITKEIVELHGGRIWVESEVGKGSRFFVWIPKDRA- 219 Y013_MYCPN ----IKEIKVEQKAQGEQIKELQVEQKAQ----------- 110 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . * . :

HPK1

This is the most common type histidine protein kinase. PhoR and most hybrid kinases, including all known eukaryotic histidine kinases, are members of this subfamily (Table 4, Figure 1). They exhibit all the characteristic HPK sequence fingerprints, ie, the H-, X-, N-, D-, F-, and Gboxes:

H-box: Fhxxh(S/T/A)H(D/E)h(R/K)TPLxxh

X-box: conserved hydrophobicity pattern

N-box: (D/N)xxxhxxhhxNLhxNAh.(F/H/Y)(S/T)

D-box, F-box: hxhxhxDxGxGhxxxxxxxhFxxF

G-box: GGxGLGLxhhxxhhxxxxGxhxhxxxxxxGx xFxhxh

The HPK2 subfamily (Table 4, Fig. 1) contains EnvZ, one of the most thoroughly investigated histidine kinases.14–15 The HPK2a subgroup is distinct from HPK2b in that these proteins have a phenylalanine 6 residues proximal to the phospho-accepting histidine. Members of HPK2b have a leucine or methionine at this position. The 2b group has an arginine at position 3 after the conserved proline of the H-box. This arginine seems to be diagnostic for group 2b since only one sequence of group 2a and no kinase from any other group has a positively charged residue at this position.

HPK3

These kinases are very closely related to the HPK1 and HPK2 subfamilies, but do not clearly fall into either category(Table 4, Fig. 1). In three of the four proteins of the HPK3a group the H-box histidine is followed by a serine instead of the acidic residue that is most commonly found at this position (Fig. 1). The only other kinases with this general characteristic are the CheA’s, ie, HPK9. Another noteworthy feature of the HPK3a’s is the lack of a second phenylalanine in the F-box. The three kinases in the HPK3b class have an asparagine rather than a threonine preceding the conserved H-box proline (Fig. 1). Located three residues downstream from the conserved histidine, this residue would be predicted to lie adjacent to the phosphorylation site on one face of an alpha-helix.

Eight receiver domain families

Similarly, there is a body of structural information known on two-component systems, in particular, analysis classifies TCS into class I, hybrid type of class I and class II according to their domain composition. Even thoguh sequence similarity of sensor histidine kinases is not high, there is amino acid motifs of H,N,G1,F,G2 boxes, ie, Hbox(HExxxP) contains phosphorylated His,N(NLxxxN),G1(DxGxG),F(FxPF) and G2(GxGxGL) create the ATP binding site and the catalytic sites in the catalytic domain.

In hybrid type HK the histidine kinase is followed by Asp containing receiver domain and a His-containing phosphotransfer domain. Class II HK has five domains per monomer.

Modification by Connector Proteins

TCSs can actually be modified by additional proteins. In particular, connector-modules modify or enhance transmission, can increase the binding to regulator proteins or can even be additional proteins within a TCS.

The following summary contains possible connector domain analogues to SafA and their PSI-BLAST values of selected organisms.

Species distribution of HisKa and response regulator domains. Visualized with PFAM sunburst.

Design and modification of individual TCS: HisKA substitutions.

Notes: Distance matrix (Swiss-Prot protein codes) of the HisKA environment of selected species (residues from 221 to 289 ENVZ_ECOLI numbering): We predict in accordance with earlier experimental data (Skerker et al, 2008) the environment to be interchangeable, however, we show that for the different sequences the distances between individual examples are often much larger and hence an exact replacement or switch of function may be more challenging. This is specifically compared by the data below which allow planning of protein design experiments between the 42 compared TCS.

Table S1.

Domain combinations occurring most often in PFAM regarding sensor and response regulator proteins.

| Combination of sensor domains | Response regulator domains |

|---|---|

| HisKA + | HATPase_c + |

| (n * HAMP + m * | |

| PAS + p * Hpt)1 | |

| HATPase_c | Response_reg * s2 |

| HAMP | Response_reg + GerE |

| His_kinase + | Response_reg + HTH |

| HATPase_c | |

| HisKA + | Response_reg + LytTR |

| HATPase_c | |

| HWE_HK | Response_reg + HisKA domain |

| HisKA_2 + | Response_reg + CheB or CheW |

| HATPase_c | |

| HisKA_2 | Response_reg + Sigma |

| HisKA_3 | Response_reg + Spo |

| HisKA | Response_reg + GGDEF |

| Response_reg + EAL | |

| Response_reg + HDOD |

Notes: PFAM-family combinations in sensor and response regulator proteins are listed ordered by the frequency of occurrence (top ranked combination are shown at the top; however, each sensor domain combination can combine with any of the response domain combinations). Lower case letters symbolize domain replicates within a specific combination.

m: 0–6, n: 0–10, p: 1–9;

s: 1–2;

Table S2.

Lists promotor site for TCS involved proteins.

Table S3.

Pfam search for BCKD_MOUSE.

| Pfam-A | Description | Entry type | Seq start | Seq end | HMM From | To | Bits score | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HATPase_c | Histidine kinase-, DNA gyrase B-, and HSP90-like ATPase | Domain | 7 | 135 | 12 | 126 | 68.3 | 5.8e–19 |

Table S4.

Pfam search.

| Pfam-A | Description | Entry type | Seq start | Seq end | HMM from | To | Bits score | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response_reg dicdi | Response | Domain | 2 | 86 | 1 | 80 | 24.6 | 2.6e-06 |

| Response_reg AGLZ | Response | Regulator | Receiver | Domain | Domain | 2 | 83 | 1 |

Table S5.

SafA similar proteins.

| Organism | Protein Id | Protein name | Score | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli 0157 | NP_310132.1 | Hypothetical protein ECs2105 | 100 | 5e-23 |

| E. coli 0157 | ZP_02799272.2 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 88.2 | 2e-19 |

| E. coli UTI89 | YP_540723.1 | Hypothetical protein UTI89_C1714 | 97.4 | 2e-22 |

|

Shigella flexneri 2a str. 24577T |

NP_837211.1 | Hypothetical protein S1655 | 91.5 | 2e-17 |

Table S6.

TCS domains in several organisms.

| Organismus | Mist-annotation/ScanProsite or SMART count1 | |

|---|---|---|

| HisKa | Response reg | |

| E. coli K-12 | 29/77 | 31/39 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (STAAN) | 18/30 | 17/285 |

| Listerien monocytogenes (LISMO) EGD | 16/56 | 16/54 |

| Arabidospis thaliana (ARATH) | 16/61 | 22/285 |

| Zea mays (MAIZE) | 20/25 | 22/44 |

Notes:

The Table compares the annotated number of TCS domains in MIST database that are known to belong to TCS versus the TCS domains found by motif similarity using ScanProsite or domain similarity using SMART. The two plant examples are not yet annotated in MIST, however, for these organisms there are in Arabidopsis 16 His protein kinases (Hwang et al, Plant Physiology 2002, 129:500–515) and 22 response regulators (ARRs), 12 of which contain a Myb-like DNA binding domain called ARRM (type B). The remainder (type A) possess no apparent functional unit other than a signal receiver domain containing two aspartate and one lysine residues (DDK) at invariant positions, and their genes are transcriptionally induced by cytokinins without de novo protein synthesis. The type B members, ARR1 and ARR2, bind DNA in a sequence-specific manner and work as transcriptional activators (Database of Arabidopsis transcription factors, http://datf.cbi.pku.edu.cn/browsefamily.php?familyname=GARP-ARR-B). In Maize there are 11 cytokinin receptory, 9 phosphotransfer proteins and 22 response regulators (Chu et al, Genet Mol Res. 2011;10(4):3316–3330).

References