Abstract

Ligands acting at the benzodiazepine (BZ) site of γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors currently are the most widely used hypnotics. BZs such as diazepam (Dz) potentiate GABAA receptor activation. To determine the GABAA receptor subtypes that mediate the hypnotic action of Dz wild-type mice and mice that harbor Dz-insensitive α1 GABAA receptors [α1 (H101R) mice] were compared. Sleep latency and the amount of sleep after Dz treatment were not affected by the point mutation. An initial reduction of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep also occurred equally in both genotypes. Furthermore, the Dz-induced changes in the sleep and waking electroencephalogram (EEG) spectra, the increase in power density above 21 Hz in non-REM sleep and waking, and the suppression of slow-wave activity (SWA; EEG power in the 0.75- to 4.0-Hz band) in non-REM sleep were present in both genotypes. Surprisingly, these effects were even more pronounced in α1(H101R) mice and sleep continuity was enhanced by Dz only in the mutants. Interestingly, Dz did not affect the initial surge of SWA at the transitions to sleep, indicating that the SWA-generating mechanisms are not impaired by the BZ. We conclude that the REM sleep inhibiting action of Dz and its effect on the EEG spectra in sleep and waking are mediated by GABAA receptors other than α1, i.e., α2, α3, or α5 GABAA receptors. Because α1 GABAA receptors mediate the sedative action of Dz, our results provide evidence that the hypnotic effect of Dz and its EEG “fingerprint” can be dissociated from its sedative action.

Fast synaptic inhibition in the mammalian central nervous system is largely mediated by activation of γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors. GABAA receptors are heteromeric membrane proteins that operate as GABA-gated ion channels. Most GABAA receptors are composed of α, β, and γ2 subunits with a pentameric stoichiometry (1). GABAA receptor function can be enhanced by allosteric modulators, e.g., benzodiazepines (BZ), barbiturates, and neurosteroids. This enhancement of neuronal inhibition by GABA is one of the most powerful therapeutic strategies for treatment of central nervous system diseases such as sleep disturbances, anxiety disorders, muscle spasms, and seizure disorders (2). Classical BZ like diazepam (Dz) bind to GABAA receptors that contain the α subunits α1, α2, α3 or α5, hereafter called α1, α2, α3, or α5 GABAA receptors, respectively (3). GABAA receptors containing the α4 or α6 subunits are insensitive to Dz. The α subunits show distinct patterns of distribution in the brain (4).

The α1 GABAA receptors represent ≈60% of all Dz-sensitive GABAA receptors in the brain and are found mainly in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex, thalamus, and pallidum (4). To assess the functions of this most prevalent receptor subtype in the pharmacological spectrum of Dz, a point-mutated knock-in mouse line, [α1(H101R)], in which the α1 GABAA receptors are insensitive to Dz, has been developed (5, 6). These mice represent a useful tool to distinguish between Dz actions that are mediated by α1 GABAA receptors or by GABAA receptors other than α1. Recently it was reported that α1 GABAA receptors mediate the sedative (reduction of motor activity) and amnesic actions of Dz, whereas the anxiolytic, muscle relaxant, motor impairing, and ethanol potentiating effects are mediated by GABAA receptors other than α1 (5, 7).

BZ hypnotics have distinct effects both on sleep and the sleep electroencephalogram (EEG). They induce dose-dependent increases of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, a reduction of REM sleep in humans and a typical BZ “fingerprint,” consisting of a reduction in delta activity in humans and rats, an increase of sigma activity in humans, and high-frequency activity in rats (8–15). These effects are common for agonists acting at the BZ site, irrespective of whether they are BZ or non-BZ compounds such as zolpidem and zopiclone (15–17).

To assess whether the α1 GABAA receptors mediate not only the sedative action of Dz but also its effects on sleep, the sleep EEG and motor activity were compared in α1(H101R) and wild-type mice. Surprisingly, we found that the BZ fingerprint in the sleep EEG was present in both genotypes, indicating that these changes in the sleep EEG are mediated by GABAA receptors other than α1, in contrast to the sedative action, which is mediated by α1 receptors (5, 6).

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Experiments were performed in male mice homozygous for a histidine to arginine point mutation at position 101 of the GABAA receptor α1 subunit (α1–Arg-101) and homozygous wild-type controls (α1–His101) (5). The local governmental commission for animal research approved the experiments. Mice were kept individually on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle (light: 08:00–20:00 h; ≈30 lux) at 22–24°C, in Macrolon cages (36 × 20 × 35 cm), with ad libitum food and water.

Electrodes for recording the EEG and the electromyogram and a thermistor for recording cortical temperature were implanted under deep anesthesia (50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium, i.p.) as described (18, 19). The mice were 11–13 weeks old and weighed 23–29 g before surgery. The electrodes and the thermistor were fixed to the skull with dental cement. At least 21 days were allowed for recovery and adaptation to the recording conditions.

Data Acquisition.

Motor activity was recorded by IR sensors centered above the cage. Activity counts were integrated over consecutive 1-min epochs and stored on a computer (18). The EEG and electromyogram signals were amplified, filtered, and stored with a resolution of 128 Hz (for details see ref. 20). Consecutive 4-s epochs were subjected to a fast Fourier transform routine, and EEG power density was computed for 4-s epochs in the frequency range of 0.25 to 25.0 Hz. Ambient temperature and cortical temperature were sampled at 4-s intervals.

Vigilance states were visually scored for 4-s epochs (20). Sleep latency was defined as the time elapsed between drug administration and the first consecutive NREM sleep episode lasting at least 3 min and not interrupted by more than six 4-s epochs not scored as NREM sleep. Epochs containing artifacts were identified and excluded from analysis (3.3 ± 0.3% of total recording time). The vigilance states of all epochs could be identified.

Experimental Protocol.

Mice were injected with 3 or 10 mg/kg i.p. Dz and vehicle (Veh; 0.3% Tween 80; injection volume: 5 ml/kg body weight) immediately before dark onset, and motor activity was measured for 12 h. As 3 mg/kg Dz induced only a short-lasting sedation, whereas the effect of 10 mg/kg was more prolonged, sleep was recorded after injection of an intermediate dose of 5.0 mg/kg Dz at light onset [wild type, n = 5 and α1(H101R), n = 4]. The amount of vigilance states was not affected (Table 1), however, prolonged EEG changes were observed (not shown). Therefore, sleep was investigated after a lower dose (3.0 mg/kg) in a new group of mice [wild type, n = 8; α1(H101R), n = 7] and compared with Veh. Treatments were at light onset, and recordings were performed for 12 h. To exclude residual effects of Dz, Veh was injected 2 days before Dz.

Table 1.

Sleep latency, amount of the three vigilance states (NREM sleep, REM sleep, and waking), and the NBA in NREM sleep in 12-h light periods

| Wild type (n =

8)

|

α1(H101R) (n = 7)

|

Wild

type (n = 5)

|

α1(H101R) (n = 4)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | Dz, 3 mg/kg | Veh | Dz, 3 mg/kg | Veh | Dz, 5 mg/kg | Veh | Dz, 5 mg/kg | |

| Sleep latency | 11.4 (2.4) | 9.9 (3.7) | 14.3 (2.0) | 23.0 (7.0) | 14.9 (6.1) | 41.0 (24.4) | 14.7 (6.4) | 12.3 (7.0) |

| Waking | 33.4 (1.7) | 31.1 (2.3) | 34.7 (1.2) | 35.1 (1.6) | 37.2 (2.7) | 34.6 (3.5) | 37.7 (3.1) | 42.2 (2.5) |

| NREM sleep | 55.3 (1.3) | 56.9 (2.2) | 53.1 (0.9) | 52.5 (1.7) | 51.1 (2.5) | 51.7 (3.8) | 50.7 (3.5) | 45.1 (1.8) |

| REM sleep | 11.3 (0.7) | 12.0 (0.5) | 12.2 (0.7) | 12.4 (0.7) | 11.8 (0.9) | 13.7 (0.6) | 11.7 (0.9) | 12.8 (1.1) |

| REMS/TST | 17.0 (0.9) | 17.5 (0.8) | 18.6 (0.9) | 19.2 (1.1) | 18.8 (1.4) | 21.3 (1.9) | 18.9 (2.0) | 22.0 (1.2) |

| NBA | 39.5 (2.6) | 34.9 (3.0) | 40.4 (2.8) | 26.3 (1.2)178 | 37.5 (4.7) | 36.4 (10.6) | 37.9 (5.4) | 17.9 (2.8) |

Mean sleep latency (min) and vigilance states (% of recording time) and REM sleep [% of total sleep time (REMS/TST)] for the 12-h light period after Veh (0.3% Tween 80) and Dz for α1(H101R) and wild-type mice. NBA are computed as absolute number per h of sleep. Means ± SEM.

, P < 0.04 wild type vs. α1(H101R), unpaired t test on differences Veh vs. Dz.

Data Analysis and Statistics.

Genotypes were compared by post hoc two-tailed t tests if a two-way ANOVA factor genotype or interaction genotype × 2-h interval (intervals 1–6) was significant. Overall effects within a genotype were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for repeated measures with factors condition (Veh and Dz) and 2-h intervals (intervals 1–6).

Results

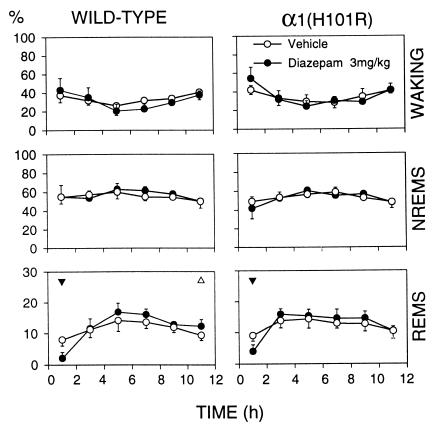

Dz had no effect on sleep latency or on the total amount of waking, NREM sleep, and REM sleep (Table 1). An initial, short-lasting reduction of REM sleep occurred in both genotypes after 3 mg/kg (Fig. 1). Cortical temperature was reduced in waking (Table 2) and in the first 2 h NREM sleep (not shown) in wild-type mice only. Despite these differences, the comparison between the genotypes did not reach significance (n.s., two-way ANOVA for repeated measures). Moreover, neither sleep latency, the amount of sleep, nor cortical temperature differed between the genotypes after Veh treatment.

Figure 1.

The vigilance states waking, NREM sleep (NREMS), and REM sleep (REMS) expressed as % of total recording time for Veh and Dz, 3.0 mg/kg, i.p. Mean 2-h values and 2 SEM for wild type (n = 8) and α1(H101R) mice; n = 7. Triangles indicate differences between Dz and the corresponding Veh interval (▴, P < 0.01; ▵, P < 0.05; paired t test). Triangle orientation indicates the direction of deviation. Two-way ANOVA factors condition (Veh, Dz) and 2-h interval: REMS, interaction condition × 2-h interval, P < 0.04 within each genotype.

Table 2.

Cortical temperature in °C over the 12-h recording in the light period

| Wild type (n =

7)

|

α1(H101R) (n = 6)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veh | Dz, 3 mg/kg | Veh | Dz, 3 mg/kg | |

| Total | 35.7 (0.07) | 35.6 (0.13) | 35.6 (0.07) | 35.5 (0.08) |

| NREM sleep | 35.5 (0.07) | 35.4 (0.12) | 35.4 (0.07) | 35.3 (0.07) |

| REM sleep | 35.6 (0.07) | 35.6 (0.16) | 35.4 (0.08) | 35.4 (0.07) |

| Waking | 36.0 (0.10) | 35.8 (0.13)178 | 36.0 (0.05) | 35.9 (0.09) |

Values are means ± SEM in parenthesis for individual vigilance states and total recording interval (Total).

, P < 0.01, difference from Veh (paired t test).

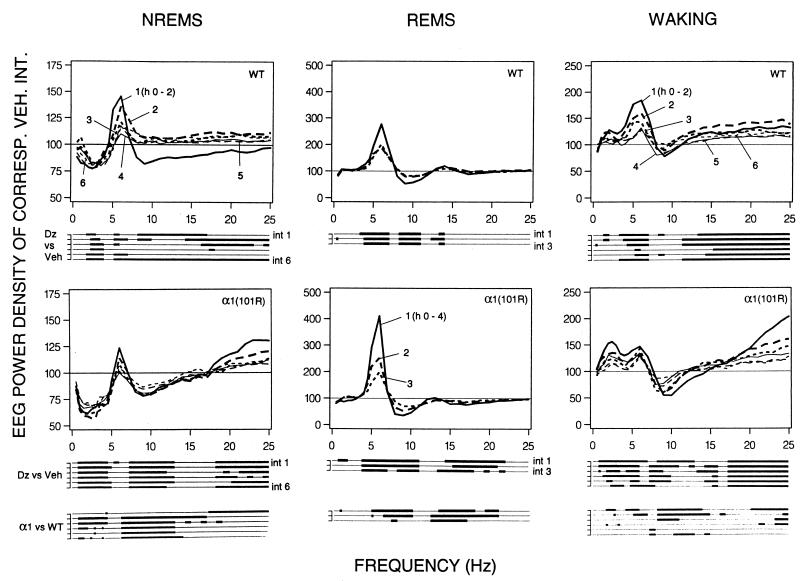

The genotypes did not differ in mean absolute EEG power density (0.25–25.0 Hz during Veh; wild type: waking 765.8 ± 78.5 μV2, NREM sleep 1,080.5 ± 131.1 μV2, REM sleep 759.4 ± 91.7 μV2; α1(H101R): waking 908.9 ± 86.7 μV2, NREM sleep 1,203.7 ± 54.9 μV2, REM sleep 832.1 ± 62.7 μV2; P > 0.1, unpaired t test). Fig. 2 illustrates the effects of 3 mg/kg Dz on the EEG spectra. After Dz EEG power in NREM sleep was reduced in both genotypes in frequencies within the delta band (0.75–4.0 Hz, Fig. 2 Left). This effect was more prominent in the mutants, encompassing a broader frequency range (0.75 to 5.0 Hz vs. 1.75 to 4.0 Hz in wild type). Although the Dz-induced changes persisted during the entire 12-h recording, the genotype differences in the delta band gradually subsided (Fig. 2 Lower Left, α1 vs. WT). Moreover, 1–2 frequency bins within the lower theta band (which in rodents encompasses 6.25–9.0 Hz) exceeded the Veh control level during most 2-h intervals in wild-type mice, whereas in α1(H101R) mice the effect was less prominent and restricted to a single bin in the first 2 h after Dz. In addition, in the mutants a prolonged decrease in power was observed in the 8.25 to 13.0-Hz band. A similar effect occurred in the first 2 h only in wild type, encompassing frequencies up to 17 Hz, which was followed by a rebound in a narrower band in hours 2–4. In the upper beta band (above 18 Hz) power was consistently above Veh in the mutants, whereas in wild-type mice no consistent effect was seen. The genotype differences within the theta and sigma (12–16 Hz) band did not subside in the course of the 12 h.

Figure 2.

EEG power density in NREM sleep (NREMS), waking, and REM sleep (REMS) for consecutive 2-h or 4-h intervals (numbers 1–6, 2-h intervals 1–6 and numbers 1–3, 4-h intervals 1–3, respectively) after Dz (3.0 mg/kg) for wild-type (WT, n = 8) and [α1(H101R), n = 7] mice. Curves connect mean values of power density of each frequency bin expressed as % of the corresponding bin and interval after Veh treatment (Veh = 100%). Values are plotted at the upper limit of each bin. Lines below the panels indicate frequency bins that differed between Dz (after significance was reached in two-way ANOVA for repeated measures) and corresponding bins after Veh (P < 0.05; two-tailed paired t test), or between α1(H101R) and wild-type mice in the effect of Dz treatment (P < 0.05; unpaired t test). No differences in EEG power density were observed between genotypes after Veh.

Dz also affected the REM sleep EEG spectra in both genotypes (Fig. 2 Middle). A long-lasting increase of power in frequencies between 3.75 and 7.0 Hz, as well as a concomitant power decrease between 8.25 and 11.0 Hz was observed. The degree of both effects was significantly larger in α1(H101R) mice (Fig. 2; α1 vs. WT). The genotype differences in the theta-band range subsided after 8 h, with the exception of a single bin. A minor, but consistent, power reduction occurred in the mutants only in frequencies between 14 and 23 Hz.

Several Dz-induced changes were present in the waking EEG. These were, with one exception, more prominent in the mutants. Power in several bins below 7.0 Hz was above Veh in both genotypes, and in α1(H101R) mice some bins between 7–13 Hz were reduced. In both genotypes power in frequencies above 14 Hz showed a prolonged increase. Especially in the first 6 h the effects were significantly larger in α1(H101R) mice in frequencies within the delta, higher theta, sigma, and higher beta band (Fig. 2 Right, α1 vs. WT).

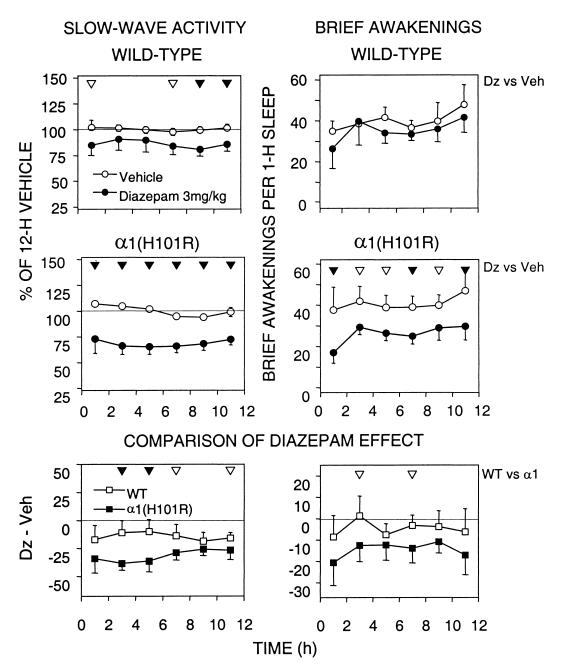

Fig. 3 Left illustrates the effect of Dz on EEG slow-wave activity (SWA; mean EEG power density in the 0.75 to 4.0-Hz range) in NREM sleep. After Dz SWA was significantly below Veh in several 2-h intervals in wild-type mice. In the α1(H101R) mice the SWA suppression persisted for the entire 12 h, and in several intervals was significantly larger in the mutants (Fig. 3 Bottom Left; WT vs. α1).

Figure 3.

Time course of SWA (mean EEG power density 0.75–4.0 Hz; Left) in NREM sleep (NREMS) and the NBA (waking episodes ≤ 16 s expressed as NBA per 1 h of total sleep) after 3 mg/kg Dz or Veh. Mean values and 2 SEM for consecutive 2-h intervals. (Top and Middle) For each individual values are expressed as % of its 12-h mean in NREMS (= 100%). Differences between Dz vs. Veh are indicated by filled (P < 0.01) and open (P < 0.05) triangles (paired t test) for wild type and α1(H101R), respectively. Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures factors condition (Veh, Dz) and 2-h interval (intervals 1–6). SWA—wild-type condition: F = 13.0; P < 0.009; wild-type interaction condition × 2-h interval: F = 1.1 n.s.; α1(H101R) condition: F = 66.4, P < 0.0002; α1(H101R) interaction condition × 2-h interval: F = 3.0 n.s. NBA—wild-type condition: F = 2.5 n.s.; wild-type interaction condition × 2-h interval: F = 1.3 n.s.; α1(H101R) condition: F = 35.3 P < 0.001; α1(H101R) interaction condition × 2-h interval, F = 1.1 n.s. (Bottom) SWA and NBA after Dz expressed as difference from the corresponding Veh interval. Triangles indicate differences between genotypes (▴: P < 0.01; ▵: P < 0.05; unpaired t test). Two-way ANOVA with factors genotype [WT, α1(H101R)] and 2-h interval (intervals 1–6). SWA: genotype, F = 41.1, P < 0.0001; interaction genotype × 2-h interval, F = 1.6 n.s. NBA: genotype, F = 17.5, P < 0.0001; interaction genotype × 2-h interval, F = 0.33 n.s.

Sleep continuity was enhanced by Dz in the mutants only (Fig. 3 Right). The decrease in the number of brief awakenings (NBA) in these mice persisted for 12 h (Table 1, Fig. 3). The 12-h values of NBA did not differ between the genotypes after Veh (Table 1). To clarify the relationship between NBA and SWA Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed for the 12-h changes in SWA and NBA after Dz. No significant correlation was found [WT, r = −0.48, P = 0.23; α1(H101R), r = 0.67, P = 0.11].

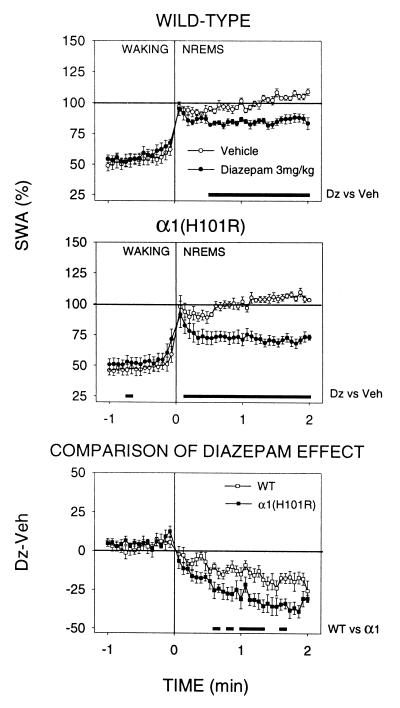

SWA was computed at the waking-NREM sleep transitions to assess the mechanisms underlying the SWA-suppressing effect of Dz (Fig. 4). The initial surge of SWA, which began in the last 4–8 s of waking before the transition and reached its maximum in the first 4-s epoch of NREM sleep, was not affected by Dz. However, once a NREM sleep episode was initiated, SWA decreased progressively until it reached a stable level after ≈28 s in wild-type mice and 16 s in α1(H101R) mice. Significant differences in the level of SWA in NREM sleep between the genotypes appeared only after 20 s (Fig. 4 Bottom). The magnitude of change between the mean 1-min SWA value in waking before the transition and the first epochs of NREM sleep did not differ between the genotypes (not shown). The computation of a narrower SWA-band corresponding to the significance in wild-type mice after Dz (1.75–4.0 Hz; Fig. 2) did not affect this result (not shown).

Figure 4.

(Top and Middle) SWA (EEG power 0.75–4.0 Hz) at the waking-NREM sleep transition after Veh and Dz treatment. Mean values [n = 8 wild type, n = 7 α1(H101R)] for 4-s epochs during 1 min of waking before the transition (Time 0) and 2 min NREM sleep after the transition. SWA is expressed as % of the individual 12-h value of SWA in NREM sleep after Veh treatment. The number of transitions was similar for both genotypes and for Veh and Dz (mean values ± SEM between 36.4 ± 1.2 and 41.4 ± 1.2). (Bottom) The curves represent the difference of SWA between corresponding epochs of Veh and Dz treatment for the two genotypes. Lines above the abscissae: differences between corresponding 4-s epochs of Veh vs. Dz treatment or wild type vs. α1(H101R); P < 0.05, paired t test or unpaired t test, respectively.

Motor activity was reduced by Dz (3 and 10 mg/kg) in wild-type mice but not in α1(H101R) mice. The effect was significant for the first 2 h (not shown). No differences in motor activity between the genotypes were observed on the baseline preinjection day or after Veh (not shown).

Discussion

Hypnotic effects are classically considered to involve more pronounced depression of the central nervous system than sedation, and this can typically be achieved by increasing the dose of sedative-hypnotic drugs. A hypnotic should mimic the changes observed after physiological sleep pressure and have no residual effects (21). These changes have been consistently reported in humans and many other species after sleep deprivation and include shortening of sleep latency, increase of total sleep time and sleep efficiency, and enhancement of EEG power in the delta frequency range (see refs. 22 and 23 for reviews). The effects of Dz on sleep and EEG parameters have not been reported previously in mice. Neither 3 nor 5 mg/kg Dz shortened sleep latency or increased the amount of sleep. The decrease of cortical temperature in waking observed after Dz could be a consequence of a mild sedation, because brain temperature decreases when behavior progresses from active to quiet waking and to NREM sleep (20). This interpretation is consistent with the decrease of motor activity we observed in wild type after Dz.

Sleep efficiency was increased only in the mutants, as seen by the marked reduction of sleep fragmentation (lower amount of brief awakenings). The 12-h values of NBA after Veh were the same in both genotypes and are in the range of those reported previously in mice (18–22). The discrepancy between the increase of sleep continuity and the reduction of power in the lower EEG frequencies is consistent with the findings in humans, where an acute dose of a BZ such as flunitrazepam and midazolam or the BZ-site ligands zopiclone and zolpidem suppressed SWA (9, 10, 13, 15, 24, 25) with a concomitant reduction in movement activity (9, 24, 26). Under conditions of enhanced physiological sleep pressure sleep fragmentation is low, and in the rat the SWA increase in NREM sleep is negatively correlated with NBA (27). Thus, more intense sleep is accompanied by less brief awakenings. Paradoxically, the decrease of SWA after Dz was accompanied by an increase in sleep continuity in the mutants.

In addition, Dz initially suppressed REM sleep, which corresponds to the findings reported for many BZ- and non-BZ hypnotics in humans (for a review see ref. 15) and the rat (14, 28). This effect occurred in mice of both genotypes and therefore does not seem to be mediated by the α1 GABAA receptor subtype.

The Dz-induced EEG changes were marked and prolonged. EEG power in several frequency bands was either above or below Veh for the entire 12 h. These effects can be separated into those that were restricted to the sleep EEG and others that encompassed also the waking spectra. The decrease of power in the delta range (0.75–4.0 Hz) was sleep-specific, because an opposite change occurred in waking. An increase in delta activity in waking has been found in rats and mice also during prolonged waking (19, 27). In contrast, the increase in power in the lower theta (5–6 Hz) and in the beta (above 15 Hz) frequencies, as well as the suppression of power in the spindle range (12–16 Hz) was not specific for sleep. A shift of EEG theta power toward lower frequencies was observed in all vigilance states (Fig. 2). A Dz-induced shift in theta peak frequency was reported for the hippocampal EEG when mice were forced to walk on a treadmill (29).

Despite the progress in the understanding of the generation of EEG delta activity (30–33), the mechanisms leading to its BZ-induced reduction or its increase after sleep deprivation are still unknown. Our data indicate that the suppression of SWA is not mediated by the α1 GABAA receptor. It is remarkable that despite the pronounced SWA-suppressing effect of Dz the mechanisms leading to the transition of waking to NREM sleep were not affected. This finding is comparable to the results in humans, where despite the general attenuation of EEG slow waves after different BZ compounds, their gradual buildup at the beginning of a NREM sleep episode persisted, albeit at a slower rate (11, 34). The recurrent inhibition within the reticular thalamic nucleus, which is mediated by GABAA receptors (most likely of the subunit composition α3β3γ2) (35), leads to a reduction of synchrony of thalamocortical oscillations, which in turn lead to changes in synchronization of the sleep EEG (32, 33, 36, 37). It is possible that these mechanisms within the reticular thalamic nucleus are affected by Dz. The α1 GABAA receptor is the most abundant GABAA receptor subtype in the cerebral cortex, and it is predominantly expressed in interneurons (4). Our study, however, revealed that this receptor subtype is apparently not critical for mediating the Dz-induced changes in the sleep EEG, suggesting that subcortical neurons most likely play an essential role.

The effects of Dz on the EEG in mice are similar to those found in rats, where SWA in NREM sleep was reduced and frequencies above 13 Hz were enhanced by 3 mg/kg midazolam. As in mice, power in the waking spectrum was enhanced in frequencies above 10 Hz (14). This increase is consistent with the induction of high-frequency power in waking in rats after tiagabine, a centrally active selective GABA-reuptake inhibitor (38, 39).

Many of the Dz-induced changes in the sleep EEG were more prominent in α1(H101R) mice than in wild type. In addition, Dz reduced sleep fragmentation only in α1(H101R) mice. It is possible that in the mutants the effects of Dz are unhampered by actions mediated via GABAA α1 receptors, such as e.g., the sedative effect (5, 6).

It should be noted that none of the measures differed significantly between the mutants and wild-type mice after Veh injection. This result is consistent with the data showing that the point mutation α1(H101R) does not affect the response of the receptor to GABA (5, 40), thereby not impairing the physiological functions.

The widely used hypnotic zolpidem displays some selectivity for the α1 GABAA receptor subtype (3), thus inviting speculations that this subtype may mediate the hypnotic activity of BZ site ligands. Our study shows, however, that the Dz effect on specific aspects of sleep, such as the BZ fingerprint in the sleep EEG is mediated by GABAA receptors other than α1. In contrast, its sedative effect has been shown to be mediated by α1GABAA receptors (5, 6). This suggests that the sedative and the EEG effects of BZ site ligands are mediated by different molecular and neuronal substrates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. Schwierin for assistance with the experiments and data analysis and Drs. P. Achermann, A. Borbély, and H. Möhler for comments on the manuscript. The study was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grants 31–42500-94 (I.T.), 821B-059799 (C.K.), and 3100–049754.96/1 (U.R.).

Abbreviations

- GABAA

γ-aminobutyric acid type A

- BZ

benzodiazepine

- Dz

diazepam

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- NBA

number of brief awakenings

- REM

rapid eye movement

- NREM

non-REM

- SWA

slow-wave activity

- Veh

vehicle

- n.s.

not significant

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Barnard E A. In: Pharmacology of GABA and Glycine Neurotransmission, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 150. Möhler H, editor. Heidelberg: Springer; 2001. pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Möhler H. In: Pharmacology of GABA and Glycine Neurotransmission, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 150. Möhler H, editor. Heidelberg: Springer; 2001. pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Möhler H, Benke D, Fritschy J, Benson J. In: GABA in the Nervous System: The View at Fifty Years. Martin D L, Olsen R W, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2001. pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritschy J M, Möhler H. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudolph U, Crestani F, Benke D, Brünig I, Benson J A, Fritschy J-M, Martin J R, Bluethmann H, Möhler H. Nature (London) 1999;401:796–800. doi: 10.1038/44579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKernan R M, Rosahl T W, Reynolds D S, Sur C, Wafford K A, Atack J R, Farrar S, Myers J, Cook G, Ferris L, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:587–592. doi: 10.1038/75761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudolph U, Crestani F, Möhler H. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borbély A A, Mattmann P, Loepfe M, Fellmann I, Gerne M, Strauch I, Lehmann D. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;89:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borbély A A, Mattmann P, Loepfe M, Strauch I, Lehmann D. Hum Neurobiol. 1985;4:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trachsel L, Dijk D J, Brunner D, Klene C, Borbély A A. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990;3:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borbély A A, Achermann P. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;195:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aeschbach D, Cajochen C, Tobler I, Dijk D J, Borbély A A. Psychopharmacology. 1994;114:209–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02244838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aeschbach D, Dijk D J, Trachsel L, Brunner D P, Borbély A A. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;11:237–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1380110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lancel M, Crönlein T A M, Faulhaber J. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landolt H P, Gillin J C. CNS Drugs. 2000;13:185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancel M. Sleep. 1999;22:33–42. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landolt H P, Finelli L A, Roth C, Buck A, Achermann P, Borbély A A. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:175–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobler I, Gaus S E, Deboer T, Achermann P, Fischer M, Rülicke T, Moser B, Oesch B, McBride P A, Manson J C. Nature (London) 1996;380:639–642. doi: 10.1038/380639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber R, Deboer T, Tobler I. Brain Res. 2000;857:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobler I, Deboer T, Fischer M. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1869–1879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01869.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borbély A A, Tobler I. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:605–670. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borbély A A, Achermann P. In: Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Kryger M H, Roth T, Dement W C, editors. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tobler I. In: Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Kryger M H, Roth T, Dement W C, editors. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaillard J M, Schulz P, Tissot R. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1973;6:207–217. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunner D P, Dijk D J, Münch M, Borbély A A. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02244546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borbély A A. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;18:83S–86S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franken P, Dijk D J, Tobler I, Borbély A A. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R198–R208. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meltzer L T, Serpa K A. Drug Dev Res. 1988;14:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caudarella M, Durkin T, Galey D, Jeantet Y, Jaffard R. Brain Res. 1987;435:202–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch J C, Fourment A, Marc M E. Brain Res. 1983;259:308–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick D A, Bal T. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:185–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steriade M, Curro Dossi R, Nuñez A. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3200–3217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03200.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steriade M, McCormick D A, Sejnowski T J. Science. 1993;262:679–685. doi: 10.1126/science.8235588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achermann P, Borbély A A. Hum Neurobiol. 1987;6:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huntsman M M, Porcello D M, Homanics G E, DeLorey T M, Huguenard J R. Science. 1999;283:541–543. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amzica F, Steriade M. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;107:69–83. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(98)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amzica F, Steriade M. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 2000;60:229–245. doi: 10.55782/ane-2000-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coenen A M L, Blezer E H M, Luijtelaar E L J M. Epilepsy Res. 1995;21:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lancel M, Faulhaber J, Deisz R A. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:1471–1477. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benson J A, Löw K, Keist R, Möhler H, Rudolph U. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:400–404. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]