Abstract

Emotion-cognition interactions are critical in goal-directed behavior and may be disrupted in psychopathology. Growing evidence also suggests that emotion-cognition interactions are modulated by genetic variation, including genetic variation in the serotonin system. The goal of the current study was to examine the impact of threat-related distracters and serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR/rs25531) on cognitive task performance in healthy females. Using a novel threat-distracter version of the Multi-Source Interference Task specifically designed to probe emotion-cognition interactions, we demonstrate a robust and temporally dynamic modulation of cognitive interference effects by threat-related distracters relative to other distracter types and relative to no-distracter condition. We further show that threat-related distracters have dissociable and opposite effects on cognitive task performance in easy and difficult task conditions, operationalized as the level of response interference that has to be surmounted to produce a correct response. Finally, we present evidence that the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype in females modulates susceptibility to cognitive interference in a global fashion, across all distracter conditions, and irrespective of the emotional salience of distracters, rather than specifically in the presence of threat-related distracters. Taken together, these results add to our understanding of the processes through which threat-related distracters affect cognitive processing, and have implications for our understanding of disorders in which threat signals have a detrimental effect on cognition, including depression and anxiety disorders.

Keywords: cognition, emotion, interference resolution, threat, serotonin transporter gene, 5-HTTLPR, MSIT

Introduction

The ability to successfully carry out a task despite interference from task-irrelevant stimuli is a crucial requirement for goal-directed behavior. According to accepted models of selective attention and cognitive-control, task-irrelevant stimuli interfere with cognitive task performance by competing with task-relevant stimuli for attentional and response-selection resources (Desimone and Duncan, 1995; Miller and Cohen, 2001). However, the impact of distracters on task performance – or conversely, our ability to resist interference from these distracters – can vary considerably, depending on the attributes of the distracters and the attributes of the task itself (Lavie, 2005), as well as on individual differences in susceptibility to various distracters.

Critically, with respect to distracter attributes, such interference can come from both neutral and emotionally salient stimuli, highlighting the fact that emotional and cognitive processes are closely interrelated, giving rise to complex and bidirectional emotion-cognition interactions (Davidson, 2003; Blair et al., 2007). In particular, if neutral distracters impair task performance, threat-related distracters should be even more effective in high-jacking attention and interfering with the task at hand due to the preferential processing of threat stimuli over non-threat stimuli in the brain. This rapid and automatic processing of threat signals is possible because the amygdala receives threat-related information through a fast subcortical pathway as well as through a slower cortical route (Romanski and LeDoux, 1992; Morris et al., 1999), a finding supported by functional neuroimaging studies showing that the amygdala responds to threat stimuli that are outside of attentional focus or conscious awareness (Whalen et al., 1998; Vuilleumier et al., 2001). From an evolutionary perspective, in humans as in many other species, such preferential processing of potential threat signals serves the adaptive function of facilitating rapid threat detection and fight-or-flight responses essential for survival (Ohman and Mineka, 2001). However, although supported by some studies (Vuilleumier et al., 2001; Dolcos and McCarthy, 2006; Blair et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2008), such increased distractability by threat-related distracters relative to neutral distracters in behavioral measures has not been consistently demonstrated in healthy subjects (Bar-Haim et al., 2007), suggesting that additional modulatory factors may be at play.

Neuroimaging evidence also suggests that the effects of threat distracters on interference processing may dynamically change over the time-course of the task, because the amygdala response to threat stimuli is temporally dynamic due to both habituation and regulation processes. Salient or novel stimuli initially elicit a strong neural and behavioral response, because they may signal threat or reward, and are thus potentially important to the organism’s survival. Habituation refers to a diminished reactivity to a specific stimulus or stimulus class following repeated presentation with no important consequences for the organism, and it is believed to serve an adaptive function of preserving cognitive and behavioral resources and allowing continuous vigilance (Wright et al., 2001). Growing evidence from neuroimaging studies in humans shows that the amygdala habituates to repeatedly presented threat stimuli both in healthy individuals (Breiter et al., 1996; Whalen et al., 1998; Wright et al., 2001) and in patients with anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (Shin et al., 2005). In addition, neuroimaging studies of emotion regulation show a decrease in amygdala response to threat-related stimuli when human subjects actively regulate their emotional response using cognitive-control strategies such as reappraisal, distraction, or suppression (Ochsner et al., 2002; Phan et al., 2005; Eippert et al., 2007; Kim and Hamann, 2007; Wager et al., 2008; McRae et al., 2010), and convergent results have been obtained in animals in the context of fear extinction (Quirk and Beer, 2006; Hartley and Phelps, 2010). This temporally dynamic character of amygdala response to threat stimuli may also be a factor modulating threat-distracter effects on cognitive task performance.

Another important factor that may modulate – or obscure – threat-distracter effects on cognitive task performance is the difficulty level of the task itself. For instance, high perceptual load has been shown to decrease distracter effects relative to low perceptual load for neutral distracters (Rees et al., 1997), although salient distracters such as images of human faces appear to escape this modulation (Lavie et al., 2003). In contrast, high cognitive load increases distracter effects relative to low cognitive load (Lavie, 2005). In particular, a task that is too easy to perform may not allow detection of threat-distracter effects due to ceiling effects in performance, an issue particularly relevant to studies of healthy adults. Ideally, therefore, the impact of threat distracters should be investigated and compared in two different task conditions varying in difficulty, or in the level of cognitive demand required to successfully perform the task.

Finally, growing evidence suggests that common genetic variation in the serotonin system modulates both emotional reactivity and cognitive processing in the human brain, and may also modulate the impact of threat distracters on cognitive task performance. Serotonin, or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is known to be involved in a range of behavioral control processes (Cools et al., 2008, 2011; Dayan and Huys, 2009). Serotonergic neurons densely innervate the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), and the amygdala (Hensler, 2006), the key brain circuits involved in resolving interference (Carter et al., 1999) as well as integrating emotional and cognitive influences on behavior (Barbas, 2000; Bechara et al., 2000). Importantly, the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) contains a well-studied promoter polymorphism (5-HTT-linked polymorphic region, or 5-HTTLPR; Heils et al., 1996). The short (S) allele, consisting of 14 repeats, has been associated with decreased transporter expression and decreased 5-HT uptake in vitro, compared to the long (L) allele with 16 repeats (Heils et al., 1996; Lesch et al., 1996). In addition, an A → G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within the 5-HTTLPR (rs25531) produces LA and LG alleles, with the LG allele being functionally equivalent to the S allele (Hu et al., 2006). With respect to emotional and stressor reactivity, the S allele has been associated with higher measures of anxiety-related personality traits such as neuroticism (Lesch et al., 1996; Sen et al., 2004) and with an increased attentional bias to negative emotional stimuli such as images of spiders (Osinsky et al., 2008) relative to the L allele. The S allele has also been linked to a greater susceptibility to depression, depressive symptoms and suicide following adverse early-life experiences or stressful life events in adulthood (Caspi et al., 2003; Eley et al., 2004; Kendler et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2006; Zalsman et al., 2006), findings supported by a recent meta-analysis (Karg et al., 2011, although see Risch et al., 2009). Converging evidence from neuroimaging studies shows that the S or LG allele carriers display a heightened amygdala response to threat stimuli (Hariri et al., 2002, 2005; Dannlowski et al., 2007, 2010; Munafo et al., 2008) and an increased functional connectivity between the amygdala and VMPFC during the processing of threat stimuli (Heinz et al., 2005; Pezawas et al., 2005; Friedel et al., 2009), relative to the L/L or LA/LA group.

Growing evidence also suggests that the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 modulation extends to cognitive processes (Homberg and Lesch, 2010). Although improved cognitive function in the S or LG allele carriers relative to L/L or LA/LA homozygotes has also been reported (Roiser et al., 2007; Borg et al., 2009), a majority of studies have shown that the S or LG allele is associated with a relative impairment in cognitive task performance relative to the L or LA allele (da Rocha et al., 2008; Holmes et al., 2010), including dose effects of the SLG allele on disadvantageous choices in the Iowa Gambling Task (Homberg et al., 2008) and on impulsive responding in the Continuous Performance Task (Walderhaug et al., 2010, although see Lage et al., 2011). Studies of 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 modulation of cognitive interference effects remain few in number. Using a simple flanker interference task, one group (Holmes et al., 2010) reported altered post-error behavioral adjustments in the S or LG carriers relative to the LA/LA group, while another larger study (Olvet et al., 2010) found no effect of 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype on task performance. However, both studies may have been hindered by ceiling effects in task performance, making subtle genetic effects difficult to detect.

In the current study, we employed a novel and demanding threat-distracter version of the Multi-Source Interference Task (MSIT; Bush and Shin, 2006) in healthy females genotyped for the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 promoter polymorphism, in order to examine the impact of threat-related distracters and 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype on cognitive task performance. Based on previous studies (Vuilleumier et al., 2001; Dolcos and McCarthy, 2006; Blair et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2008, although see Bar-Haim et al., 2007), we hypothesized that threat distracters would potentiate interference effects relative to other distracter types and relative to a no-distracter condition. With respect to genetic effects, the simplest model is that functional variants affect gene transcription and protein function in a dose-dependent manner, without dominance, and this model is supported by some evidence for additive effects of the SLG allele on cognitive task performance (Homberg et al., 2008; Walderhaug et al., 2010) as well as on reactivity to environmental adversity (Caspi et al., 2003). Although non-additive effects have also been reported (Kendler et al., 2005), these reports have not been consistent and may be due to ceiling effects in measurement. Therefore, we expected that the SLG allele of 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 would increase interference effects in a dose-dependent or additive manner, such that the effect of genotype on interference would follow a specific order: LA/LA < LA/SLG < SLG/SLG. We further tested two competing hypotheses about the scope of 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 effects on cognitive task performance. Specifically, genetic effects could be present exclusively in the threat-distracter condition, or alternatively, genetic effects could extend to all distracter conditions, irrespective of emotional salience of distracters. We also tested whether the effects of threat distracters change over the time-course of the task, and whether these effects are modulated by task difficulty. We expected that threat distracter effects would decrease over time due to habituation and regulation processes, and that the effects of threat distracters would be greater in the more difficult incongruent task condition compared to the easier congruent task condition.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Seventy-one healthy, right-handed Caucasian females aged 18–34 years (M = 23.0 years, SD = 4.0 years) participated in the study. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Exclusion criteria included any serious medical condition, head injury or trauma, lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric illness, current use of a psychoactive medication, and smoking. Only females were studied at this stage, in order to maximize the power to detect genetic modulation of threat-distracter effects in light of prior evidence of interactions between sex hormones and serotonin transporter gene variation on threat reactivity (Josephs et al., 2012), as well as sex differences in the serotonin system (Jovanovic et al., 2008) and in the processing of emotional stimuli in the brain (Klein et al., 2003; Wrase et al., 2003). The study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School IRB and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Task: Threat-distracter MSIT

We employed a modified version of the MSIT (Bush et al., 2003; Bush and Shin, 2006). The MSIT is a validated response-interference paradigm which combines the sources of interference from Erikson, Stroop, and Simon tasks, in order to maximally tax the interference processing associated with the ACC (Bush et al., 2003). The MSIT has been shown to produce a robust and temporally stable interference effect both in reaction times (RTs) and in accuracy (Bush et al., 2003).

In the MSIT, subjects were presented with a set of three numbers from 0 to 3, one of which was different from the other two (the oddball number). Subjects were instructed to indicate the identity of the oddball number with a corresponding key press: a key press with the index finger if the oddball number was “1,” with the middle finger if the oddball number was “2,” and with the ring finger if the oddball number was “3.” On congruent trials, the identity of the oddball number corresponds to its location and the other two numbers are 0’s, not related to any valid key press response. On incongruent trials, the identity of the oddball number is incongruent with its position and the other two numbers are related to competing key press responses, resulting in stimulus-response incompatibility and response interference. The incongruent condition vs. congruent condition contrast yields the interference effect in RTs (Incongruent RT – Congruent RT) and interference effect in accuracy (Congruent Accuracy – Incongruent Accuracy).

We modified the MSIT to include three categories of task-irrelevant flanker distracters, threat, neutral, and scrambled, in addition to the null distracter condition. Threat distracters were images of human faces signaling the presence of a threat (angry or fearful expression). To isolate the effects specific to emotionally salient stimuli, we included neutral distracters (images of human faces with neutral expression), and scrambled distracters (images retaining the basic oval shape of a face but no facial features). Face stimuli were carefully selected from standardized sets (Ekman and Friesen, 1976; Gur et al., 2002; Tottenham et al., 2009). Angry and fearful faces displayed intense emotion and showed bared teeth and/or open mouth as an additional perceptual homogeneity criterion. In contrast, all neutral faces had closed mouths. All faces were Caucasian, to optimally control for potential sources of variability in emotional responses. All images were presented in grayscale, with hair and background cropped to yield an oval shape. Scrambled distracters were generated from the human face stimuli used in the other two distracter conditions by randomly rearranging the pixels within the oval while preserving the brightness of the image.

Experimental protocol

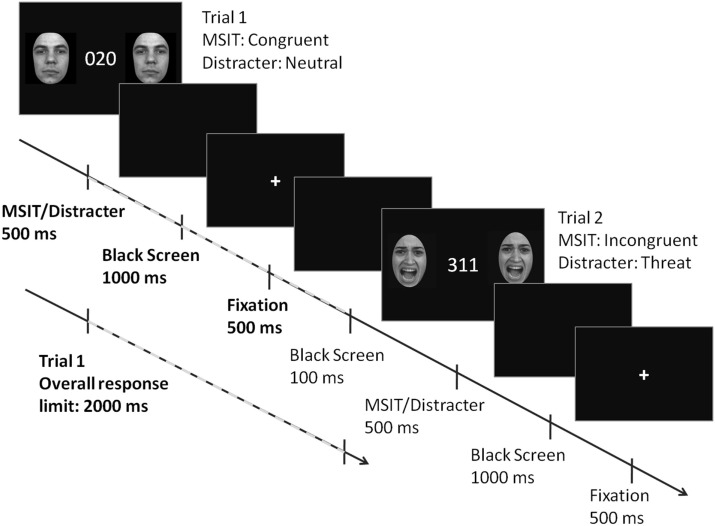

A timeline of events in a single trial is shown in Figure 1. The MSIT stimuli and two identical flanking distracter images were presented simultaneously for 500 ms, followed by a black screen for 1000 ms, and then a fixation cross for another 500 ms. The durations of these three events added up to the overall response limit of 2000 ms. A black screen presented for 100 ms separated two consecutive trials. Subjects were instructed to respond as fast and as accurately as they could. The task stimuli were presented and the key press responses collected using E-Prime 2.0.

Figure 1.

The anatomy of a trial in threat-distracter MSIT. The MSIT stimuli and two identical flanking distracter images were presented simultaneously for 500 ms, followed by a black screen for 1000 ms, and then a fixation cross for another 500 ms. The durations of these three events added up to the overall response limit of 2000 ms. A black screen (100 ms) separated two consecutive trials. Face images reproduced with permission from Gur et al. (2002).

After a self-timed tutorial in the task and a short practice run, subjects completed a total of 640 trials, divided into 2 runs, four blocks per run, 80 trials per block. A short intermission separated run 1 (blocks 1–4, a total of 320 trials) from run 2 (blocks 5–8, a total of 320 trials). The order of the trials was pseudo-randomized within each block, with the provision that no two consecutive trials (1) had the same correct response or (2) both included threat distracters. Each block lasted approximately 3 min and consisted of 40 congruent and 40 incongruent trials. Within the sets of 40 congruent and 40 incongruent trials, 10 trials included threat distracters (five angry faces, three female, two male or two female, three male; and five fearful faces, three female, two male or two female, three male), 10 trials included neutral distracters (five female, five male), 10 trials included scrambled distracters, and 10 trials were no-distracter trials (i.e., with MSIT stimuli only). The whole experiment lasted approximately 30 min.

Genotyping of 5-HTTLPR/rs25531

Genomic DNA was obtained from saliva using the Oragene saliva collection system and extracted using the protocol provided (Genotek, Ontario, Canada). The extracted DNA samples were genotyped for 5-HTTLPR and rs25531 in two steps, according to Wendland et al. (2006). In the first step, the 5-HTTLPR was amplified via polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) using site-specific forward and reverse primers, yielding “short” (14-repeat, 375 bp) and “long” (16-repeat, 419 bp) products. In the second step, the PCR product from the first step was digested with Hpa II restriction enzyme to genotype the A → G SNP (rs25531) by identifying LG (305 bp) and LA alleles. All PCR products were visualized via gel electrophoresis on a 3% agarose gel using ethidium bromide under ultraviolet (UV) light.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed in a series of steps using repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), correlations, and t-tests as implemented in SPSS 19.0. We used two behavioral indices of task performance as dependent variables, RTs on correct trials and accuracy rates. The MSIT interference effects (congruent vs. incongruent) in RTs and in accuracy were used as a global measure of the efficiency of interference processing, with greater interference effects indicating less efficient interference resolution. We conducted two separate 4 × 2 × 3 repeated-measures ANOVAs – one on interference effects in accuracy and one on interference effects in RTs – with distracter type (four levels: threat-related, neutral, scrambled, or null) and run (two levels: pre-intermission run 1 or post-intermission run 2) as within-subject factors, and 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype (three levels: 0 SLG alleles, 1 SLG alleles, or 2 SLG alleles) as a between-subject factor. Because we conducted two separate ANOVAs, we used a Bonferroni-corrected p value of 0.025 as our statistical threshold for the ANOVA results. The t-tests and Pearson’s correlations are two-tailed unless stated otherwise.

Results

Final sample

Out of the 71 healthy female subjects who participated in the study, the data from the final sample of 69 subjects were analyzed and are reported below. The data from two subjects were excluded from analysis due to concerns about task compliance and performance accuracy. One subject did not follow the task instructions and responded to the position of the oddball number rather than to its identity (M = 0.05 accuracy on incongruent trials), an occurrence reported in approximately 5% of participants in prior work using the original version of the MSIT (Bush and Shin, 2006). Another subject had a mean accuracy of 0.34 on incongruent trials, corresponding to a chance level of responding in a three-choice task.

Genotyping results

We observed the following 5-HTTLPR genotype counts (and frequencies): 25 (0.35) L/L homozygotes, 35 (0.49) L/S heterozygotes, and 11 (0.16) S/S homozygotes (Table 1). The observed genotype frequencies did not deviate from the Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (χ2 = 0.047, p = 0.828). The combined 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 functional genotypes were grouped as follows: 23 (0.32) subjects were LA/LA, 36 (0.51) subjects were LA/LGS (2 LA/LG and 34 LA/SA), and 12 (0.17) subjects were S/S (1 LG/S and 11 S/S). SLG denoted S or LG allele (Table 1). Neither the 5-HTTLPR genotype groups nor the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype groups differed in age, education, or socio-economic status (Table 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of 5-HTTLPR and 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 alleles and genotypes.

| 5-HTTLPR genotype count (frequency) |

5-HTTLPR allele count (frequency) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L/L | L/S | S/S | L | S | |||||

| 25 (0.35) | 35 (0.49) | 11 (0.16) | 85 (0.60) | 57 (0.40) | |||||

|

5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype count (frequency) |

5-HTTLPR/rs25531 allele count (frequency) |

||||||||

| Func L/L | Func L/S | Func S/S | Func L | Func S | |||||

| 23 (0.32) | 36 (0.51) | 12 (0.17) | 82 (0.58) | 60 (0.42) | |||||

| LA/LA | LA/LG | LA/S | LG/LG | LG/S | S/S | LA | LG | S | |

| 23 (0.32) | 2 (0.03) | 34 (0.48) | 0 | 1 (0.01) | 11 (0.16) | 82 (0.58) | 3 (0.02) | 57 (0.40) | |

S allele and LG allele are denoted as functional S alleles.

Table 2.

Demographic profiles of the 5-HTTLPR and 5-HTTLPR/sr25531 genotype groups.

| S/S (n = 11) | S/L (n = 33) | L/L (n = 25) | χ2 (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HTTLPR GENOTYPE | ||||

| Age (years) | 22.36 ± 3.50 | 22.39 ± 4.10 | 24.08 ± 4.18 | 19.97 (0.793) |

| Education (years) | 15.64 ± 2.20 | 15.55 ± 2.60 | 15.96 ± 1.93 | 19.51 (0.361) |

| SES | 2.18 ± 0.60 | 2.30 ± 0.53 | 2.24 ± 0.44 | 6.56 (0.363) |

| SLG/SLG (n = 12) | SLG/LA (n = 34) | LA/LA (n = 23) | χ2 (p value) | |

| 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 GENOTYPE | ||||

| Age (years) | 22.17 ± 3.41 | 22.38 ± 4.02 | 24.35 ± 4.25 | 17.67 (0.887) |

| Education (years) | 15.50 ± 2.15 | 15.56 ± 2.56 | 16.04 ± 2.00 | 18.64 (0.415) |

| SES | 2.17 ± 0.58 | 2.29 ± 0.52 | 2.26 ± 0.45 | 5.88 (0.436) |

Means and standard deviations are given. No group differences in age, education, or socio-economic status (SES) were found, as assessed with a chi-square (χ2) test.

Behavioral results

Robust MSIT interference effects across all distracter conditions

Consistent with previous reports (Bush et al., 2003; Bush and Shin, 2006), we observed a robust and highly significant MSIT interference effect (i.e., a main effect of congruency) in both measures of task performance. Overall, subjects were significantly less accurate in the incongruent condition compared to the congruent condition (congruent accuracy, M = 0.993, SE = 0.001; incongruent accuracy, M = 0.838, SE = 0.016; interference effect in accuracy, M = 0.158, SE = 0.015; F(1, 66) = 107.290, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.619), and they were also significantly slower to correctly respond in the incongruent condition compared to the congruent condition (congruent RT, M = 492 ms, SE = 11 ms; incongruent RT, M = 710 ms, SE = 16 ms; interference effect in RT, M = 218 ms, SE = 9 ms; F(1, 66) = 579.179, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.898).

The interference effects were robust and highly significant in all four distracter conditions (all p’s < 0.0001, paired-sample t-tests). The accuracy results per distracter condition are summarized in Table 3 and the RT results per distracter condition are summarized in Table 4. In addition, the interference effect on accuracy was significant in both runs (run 1, M = 0.192, SE = 0.017; t(68) = 11.077, p < 0.0001; run 2, M = 0.124, SE = 0.013; t(68) = 9.993, p < 0.0001), although it significantly diminished from run 1 to run 2, t(68) = 7.319, p < 0.0001, as also indicated by a significant two-way interaction between congruency and run on accuracy, F(1, 66) = 72.882, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.525. The interference effect in RTs was also significant in both runs (run 1, M = 221 ms, SE = 9 ms; t(68) = 26.795, p < 0.0001; run 2, M = 216 ms, SE = 9 ms; t(68) = 25.463, p < 0.0001), and did not change significantly from run 1 to run 2, t(68) = 1.496, p = 0.139. These results confirmed that MSIT produced a robust behavioral difference between the easier congruent condition and the more difficult incongruent condition, which persisted across all distracter conditions and across time.

Table 3.

Summary of accuracy data.

| Distracter type | Accuracy (proportion accurate) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSIT condition |

MSIT interference effect |

||||

| Congruent | Incongruent | Mean | t | p value | |

| Threat | 0.995 (0.013) | 0.839 (0.121) | 0.156 (0.117) | 11.002 | <0.0001 |

| Neutral | 0.993 (0.014) | 0.844 (0.126) | 0.149 (0.121) | 10.297 | <0.0001 |

| Scrambled | 0.996 (0.009) | 0.834 (0.125) | 0.161 (0.120) | 11.193 | <0.0001 |

| Null | 0.990 (0.015) | 0.856 (0.117) | 0.134 (0.110) | 10.177 | <0.0001 |

Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) are given, together with t statistics and p values for paired-sample t-tests (n = 69).

Table 4.

Summary of RT data.

| Distracter type | RT (ms) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSIT condition |

MSIT interference effect |

||||

| Congruent | Incongruent | Mean | t | p value | |

| Threat | 486 (82) | 710 (116) | 224 (72) | 26.048 | <0.0001 |

| Neutral | 489 (81) | 711 (118) | 222 (70) | 26.272 | <0.0001 |

| Scrambled | 489 (87) | 714 (117) | 225 (71) | 26.236 | <0.0001 |

| Null | 495 (84) | 701 (116) | 205 (64) | 26.781 | <0.0001 |

Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) are given, together with t statistics and p values for paired-sample t-tests (n = 69).

Threat distracters potentiate MSIT interference effects

Next, we examined whether threat-related distracters potentiated MSIT interference effects. As hypothesized, the ANOVA on interference effects yielded robust and significant main effects of distracter type on interference effects both in accuracy, F(3, 64) = 7.803, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.268, and in RTs, F(3, 64) = 6.309, p = 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.228. Convergent results were obtained from the ANOVA on accuracy and RTs, which indicated a significant two-way interaction between congruency and distracter type both on accuracy, F(3, 64) = 6.465, p = 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.233, and on RTs, F(3, 64) = 8.030, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.273. The overall interference effects in accuracy per distracter condition are given in Table 3 and the overall interference effects in RTs per distracter condition are given in Table 4. The interference effects in accuracy in the threat-distracter condition were significantly greater than in the no-distracter condition, t(68) = 3.415, p = 0.001, but not significantly greater than in the neutral-distracter condition, t(68) = 0.964, p = 0.338, or in the scrambled-distracter condition, t(68) = 1.017, p = 0.313. Similarly, the interference effects in RTs were significantly greater with threat distracters present compared to with no distracters present, t(68) = 6.308, p < 0.0001, but not significantly different compared to neutral distracters, t(68) = 0.710, p = 0.480, or scrambled distracters, t(68) = 0.211, p = 0.833. Overall, interference effects in accuracy were significantly greater in the presence of distracters compared to the no-distracter condition (with distracters: M = 0.155, SE = 0.014; no distracters: M = 0.134, SE = 0.013; t(68) = 4.056, p < 0.0001). Similarly, interference effects in RTs were significantly greater in the presence of distracters compared to the no-distracter condition (with distracters: M = 220 ms, SE = 8 ms; no distracters: M = 205 ms, SE = 8 ms; t(68) = 5.390, p < 0.0001).

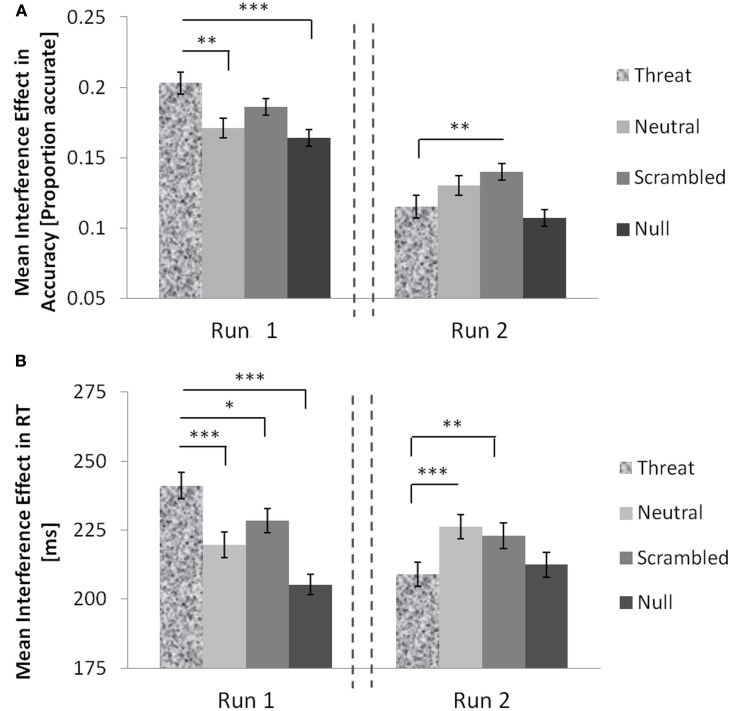

Threat-distracter effects on MSIT interference effects are transient

Overall, there was a robust and highly significant main effect of run both on accuracy [F(1, 66) = 68.309, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.509] and on RTs [F(1, 66) = 104.982, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.614]. The overall accuracy in run 1 was M = 0.903, SE = 0.009, whereas in run 2 it significantly increased to M = 0.936, SE = 0.006, t(68) = 7.249, p < 0.0001. The overall RT in run 1 was M = 625 ms, SE = 13 ms, whereas in run 2 it significantly decreased to M = 574 ms, SE = 10 ms, t(68) = 11.708, p < 0.0001. In addition, there was a significant two-way interaction between distracter type and run on interference effects in accuracy, F(3, 64) = 4.290, p = 0.008, partial eta squared = 0.167, and in RTs, F(3, 64) = 11.932, p < 0.0001, partial eta squared = 0.359. These data are summarized in Table 5 (accuracy) and Table 6 (RTs) and graphically shown in Figure 2A (accuracy) and Figure 2B (RTs).

Table 5.

Summary of accuracy data (in proportion accurate) in run 1 and run 2.

| Distracter type | Run 1 |

Run 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSIT condition |

MSIT interference effect | MSIT condition |

MSIT interference effect | |||

| Congruent | Incongruent | Congruent | Incongruent | |||

| Threat | 0.996 (0.002) | 0.788 (0.021) | 0.213 (0.020) | 0.994 (0.002) | 0.884 (0.013) | 0.113 (0.013) |

| Neutral | 0.991 (0.002) | 0.808 (0.020) | 0.184 (0.019) | 0.996 (0.002) | 0.865 (0.015) | 0.136 (0.015) |

| Scrambled | 0.993 (0.002) | 0.798 (0.019) | 0.196 (0.018) | 0.997 (0.001) | 0.860 (0.016) | 0.141 (0.015) |

| Null | 0.982 (0.004) | 0.809 (0.020) | 0.173 (0.018) | 0.997 (0.001) | 0.895 (0.014) | 0.103 (0.014) |

Means and standard errors (in parentheses) are given.

Table 6.

Summary of RT data (in ms) in run 1 and run 2.

| Distracter type | Run 1 |

Run 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSIT condition |

MSIT interference effect | MSIT condition |

MSIT interference effect | |||

| Congruent | Incongruent | Congruent | Incongruent | |||

| Threat | 502 (12) | 739 (18) | 238 (11) | 474 (10) | 682 (14) | 208 (10) |

| Neutral | 516 (13) | 734 (17) | 217 (10) | 465 (9) | 689 (15) | 224 (10) |

| Scrambled | 513 (13) | 737 (17) | 224 (10) | 471 (10) | 689 (15) | 219 (10) |

| Null | 528 (13) | 733 (17) | 204 (8) | 682 (14) | 674 (15) | 211 (10) |

Means and standard errors (in parentheses) are given.

Figure 2.

The interaction of threat distracters and time on MSIT interference effects in healthy females. Threat distracters potentiated interference effects in RTs (A) and in accuracy (B) relative to other distracter conditions in run 1 but these effects were abolished in run 2. Error bars show standard errors of the mean. The dashed lines denote an intermission. Significant two-tailed t-tests: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0001.

We also examined how the effects of threat distracters on MSIT interference effects changed over time. In run 1, threat distracters potentiated the interference effects in accuracy relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = 3.03, p = 0.004, scrambled distracters, t(68) = 1.74, p = 0.09, and no distracters, t(68) = 3.73, p < 0.0001 (Figure 2A). In contrast, in run 2 (following the intermission), the interference effects in accuracy elicited by threat distracters appeared to be lower than those elicited by neutral distracters, t(68) = −1.78, p = 0.08, or scrambled distracters, t(68) = −3.24, p = 0.002, and comparable to the interference effects observed in the no-distracter condition. Interestingly, examining congruent and incongruent trials separately revealed that threat distracters had dissociable and opposite effects on accuracy in congruent and incongruent trials across time. As expected, in run 1, subjects were less accurate on the more difficult incongruent trials in the presence of threat distracters than in the presence of neutral distracters, t(68) = −2.231, p = 0.029, or null distracters, t(68) = −2.379, p = 0.020, although not relative to scrambled distracters, t(68) = −1.203, p = 0.233. However, this relationship was reversed in run 2, and subjects appeared more accurate on incongruent trials with threat distracters relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = 1.615, p = 0.111, or scrambled distracters, t(68) = 3.010, p = 0.004, although not different in accuracy compared to incongruent trials with no distracters present, t(68) = −0.967, p = 0.337. In addition, and unexpectedly, in run 1, subjects were actually more accurate on the easy congruent trials in the presence of threat distracters relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = 2.013, p = 0.048, and relative to no distracters, t(68) = 3.570, p = 0.001, although not relative to scrambled distracters, t(68) = 0.479, p = 0.638. In run 2, these apparent performance-enhancing effects of threat distracters were abolished, and subjects’ accuracy on congruent trials in the presence of threat distracters did not significantly differ from their accuracy in the presence of neutral distracters, t(68) = −0.397, p = 0.693, scrambled distracters, t(68) = −1.413, p = 0.162, or no distracters, t(68) = −1.383, p = 0.171.

The results were similar for RTs (Figure 2B). In run 1, threat distracters potentiated the interference effects in RTs relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = 4.31, p < 0.0001, scrambled distracters, t(68) = 2.38, p = 0.020, and no distracters, t(68) = 7.36, p < 0.0001. In contrast, in run 2 (following the intermission), the interference effects in RTs observed in the threat-distracter condition were lower than in the presence of neutral distracters, t(68) = −3.87, p < 0.0001, or scrambled distracters, t(68) = −3.28, p = 0.002, and comparable to the no-distracter condition. As described above for accuracy, threat distracters appeared to have dissociable and opposite effects on the speed of correct responses in congruent and incongruent trials across time. As might be expected, in run 1, subjects were somewhat slower to correctly respond on the more difficult incongruent trials in the presence of threat distracters than in the presence of neutral distracters, t(68) = 1.626, p = 0.108, or no distracters, t(68) = 2.595, p = 0.012, although not relative to scrambled distracters, t(68) = 0.407, p = 0.685. This relationship was reversed in run 2, in which subjects were somewhat faster to correctly respond on incongruent trials with threat distracters relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = −1.987, p = 0.051, or scrambled distracters, t(68) = −2.776, p = 0.007, although still somewhat slower to correctly respond than on incongruent trials with no distracters present, t(68) = 1.847, p = 0.069. In addition, and again unexpectedly, in run 1, subjects were actually faster to accurately respond on the easy congruent trials in the presence of threat distracters relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = −5.702, p < 0.0001, scrambled distracters, t(68) = −3.848, p < 0.0001, or no distracters, t(68) = −8.615, p < 0.0001. This performance-enhancing effect of threat distracters was again transient, as seen above for accuracy. In run 2, the relationship was reversed and subjects were slower to correctly respond on congruent trials with threat distracters relative to neutral distracters, t(68) = 4.482, p < 0.0001, scrambled distracters, t(68) = 1.613, p = 0.111, or no distracters, t(68) = 5.925, p < 0.0001.

In sum, threat distracters increased the interference effect in accuracy and in RTs compared with neutral or scrambled distracters in the first half of the experiment, but these effects were reversed in the second half, following an intermission. In addition, this transient increase in interference effects in the presence of threat distracters was driven both by a threat-distracter-related impairment in performance on the more difficult incongruent trials, and, unexpectedly, by a threat-distracter-related enhancement in performance on the easy congruent trials.

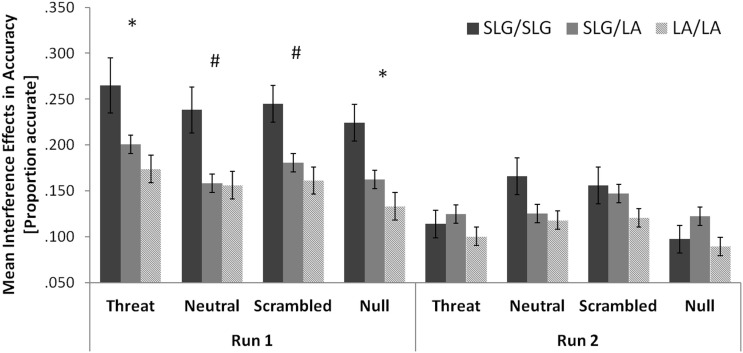

5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype modulates interference effects irrespective of emotional salience of distracters

Next, we tested whether the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype modulated the impact of threat-related distracters on cognitive task performance. Collapsing across both runs and across distracter conditions, genotype did not have a significant effect on interference effects either in accuracy, F(2, 66) = 0.983, p = 0.379, or in RTs. F(2, 66) = 0.399, p = 0.673. But there was a significant two-way interaction between genotype and run on interference effects in accuracy, F(2, 66) = 5.111, p = 0.009, partial eta squared = 0.134. These results were confirmed by the ANOVA on accuracy, which produced a significant two-way interaction between genotype and run on accuracy, F(2, 66) = 4.082, p = 0.021, partial eta squared = 0.110.

Specifically, there was an increase in interference effects in accuracy with the number of the SLG alleles, which was significant in run 1 (LA/LA: 0.156 ± 0.027; SLG/LA: 0.176 ± 0.021; SLG/SLG: 0.243 ± 0.046; r = 0.207, p = 0.044, one-tailed correlation) but did not reach significance in run 2 (LA/LA: 0.107 ± 0.021; SLG/LA: 0.130 ± 0.016; SLG/SLG: 0.133 ± 0.036; r = 0.103, p = 0.201, one-tailed correlation). A comparison of the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype groups on interference effects in accuracy separately for each distracter condition is given in Figure 3. The increase in interference effects in accuracy with the number of the SLG alleles was also significant or marginally significant in all four distracter conditions in run1 (threat: r = 0.195, p = 0.054; neutral: r = 0.170, p = 0.082; scrambled: r = 0.192, p = 0.057; null: r = 0.218, p = 0.036; all one-tailed correlations).

Figure 3.

The 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype marginally modulates interference effects in accuracy across all distracter conditions in healthy females. Error bars show standard errors of the mean. Significant or approaching significance one-tailed correlations: *p < 0.05; #p < .10.

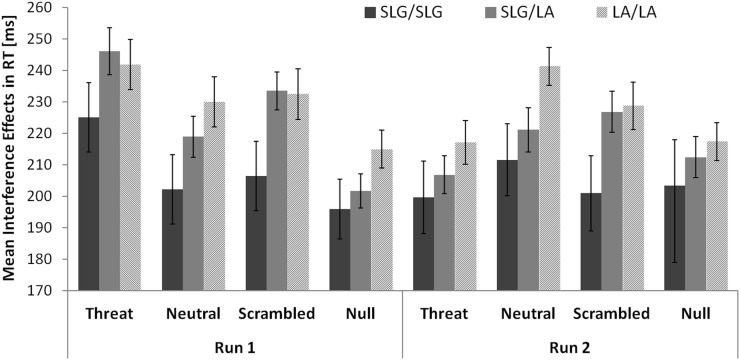

There were no comparable effects of genotype on interference effects in RTs. The magnitude of interference effects in RTs was not significantly associated with the number of SLG alleles either in run 1 (LA/LA: 230 ± 14 ms; SLG/LA: 225 ± 12.2 ms; SLG/SLG: 207 ± 20 ms; r = −0.103, p = 0.201, one-tailed correlation) or in run 2 (LA/LA: 226 ± 13 ms; SLG/LA: 217 ± 13 ms; SLG/SLG: 204 ± 24 ms; r = −0.107, p = 0.192, one-tailed correlation). A comparison of the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype groups on interference effects in RTs separately for each distracter condition is given in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

No evidence that the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype modulates interference effects in RTs in healthy females. Error bars show standard errors of the mean.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that threat-related distracters robustly modulate cognitive interference effects but the modulation dynamically changes over time. Threat-related distracters potentiated interference effects in both accuracy and in RTs relative to non-threat-related distracter types and relative to the no-distracter condition in the first half of the experiment, prior to the intermission. However, these effects were reversed in the second half of the experiment, in which the interference effects in accuracy and in RTs in the presence of threat distracters decreased below the interference effects seen in other distracter conditions, to the level observed when no distracters were present. Furthermore, by examining the congruent and incongruent conditions separately, we were able to show that this transient potentiation of interference effects by threat distracters had a dual source: on the one hand, it was due to a predicted threat-related impairment in task performance in the more difficult incongruent condition (i.e., subjects were less accurate and slower to correctly respond on incongruent trials in the presence of threat distracters relative to other distracter conditions), but on the other hand, it was also due to an unexpected threat-related enhancement of task performance in the easy congruent condition (i.e., subjects were actually more accurate and faster to correctly respond on congruent trials in the presence of threat distracters compared to other distracter conditions).

We propose that the temporally dynamic character of threat-distracter effects may be due to both habituation and regulation of amygdala response to threat stimuli. Both habitation and regulation would result in diminished amygdala reactivity. Amygdala habituation to threat stimuli has been demonstrated in neuroimaging studies involving both healthy individuals (Breiter et al., 1996; Whalen et al., 1998; Wright et al., 2001) and patients with anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (Shin et al., 2005). A separate line of neuroimaging evidence also shows a decrease in amygdala response to threat-related stimuli when people actively regulate their emotional response using cognitive-control strategies such as reappraisal, distraction, or suppression (Ochsner et al., 2002; Phan et al., 2005; Eippert et al., 2007; Kim and Hamann, 2007; Wager et al., 2008; McRae et al., 2010), with convergent evidence coming from animal studies of fear extinction (Quirk and Beer, 2006; Hartley and Phelps, 2010). We propose that both processes – habituation and regulation of amygdala response to threat stimuli – may be at work in our study. Habituation may be gradually produced by repeated harmless presentation of threat stimuli over the time-course of the task, whereas regulation may be triggered specifically by the intermission separating run 1 from run 2, giving subjects a short reprise from the demands of the task and permitting them to “take stock” and adjust their emotional response to the threat stimuli in run 2. Unfortunately, we are unable to fully dissociate the role of these two processes in the observed decrease in threat-distracter effects on cognitive performance over time using the current study design.

An intriguing finding in our study is the dissociable and opposite character of threat effects on task performance in congruent vs. incongruent task conditions. The transient increase in interference effects in the presence of threat distracters was driven both by threat-distracter-related impairment in performance on the more difficult incongruent trials, and by threat-distracter-related enhancement in performance on the easier congruent trials. Threat-related impairment in task performance has been documented before (Vuilleumier et al., 2001; Dolcos and McCarthy, 2006; Blair et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2008), although the findings have been inconsistent (Bar-Haim et al., 2007). Our data suggest that the inconsistencies may come from variable level of task difficulty, with more robust threat-related impairment observed in more difficult task conditions requiring additional time and processing steps to resolve cognitive interference arising from competing stimulus-to-response goal representations, as compared to easier task conditions involving one simple stimulus-to-response mapping.

In this respect, our finding of threat-related enhancement of task performance specific to the easier congruent task condition is informative. We speculate that this threat-related enhancement of both accuracy and speed of correct responding in the easier task condition may reflect a general priming of the motor system in response to threat signals. Our findings resonate with previous reports of enhanced response speed and force due to exposure to unpleasant stimuli during a preparation of a simple motor response (Coombes et al., 2005, 2009). Consistent with the adaptive function of rapid behavioral response to potential threat signals in the environment, threat-related stimuli may act to prime the motor system for action (Coombes et al., 2005) regardless of their status as task-relevant targets or task-irrelevant distracters. Therefore, both threat-related enhancement of task performance in the absence of cognitive interference (easier task condition) and threat-related impairment of task performance when the task requires resolution of cognitive interference (more difficult task condition) would reflect the priming of the simple, prepotent motor response – but the primed response itself would be correct in the former case and incorrect in the latter case. We further speculate that the impact of threat distracters on task performance may be mediated primarily through the effects of threat stimuli on the selection and execution of the motor response within broadly defined attentional control processes. Specifically, the detection of a potential threat signal and the subsequent activation of the threat-processing pathway could act either to directly facilitate the execution of the prepotent motor response, or to remove the inhibition of this prepotent response. In either case, performance would be expected to improve when the prepotent response is desired (e.g., in the easier congruent task condition), but suffer when the inhibition of a prepotent response in required for the selection and execution of a correct response (e.g., in the more difficult incongruent task condition). Thus, one possible strategy to reduce threat-related impairment may be to automatize the performance of a given task (i.e., to render the desired task response the prepotent response) through intense practice and habit formation, consistent with the theory of Norman and Shallice (1986).

We also report evidence that the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR/rs25531) modulates cognitive task performance in healthy female subjects in a global fashion, irrespective of the presence or emotional salience of distracters. Specifically, we observed dose effects of the SLG allele on interference effects in accuracy (but not in RTs) in the expected direction: LA/LA interference effects < SLG/LA interference effects < SLG/SLG interference effects. In addition, the modulation of interference effects by 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype was not specific to threat distracters, but instead extended to all four distracter conditions, including threat, neutral, scrambled, and no distracters. Furthermore, the genetic modulation of interference effects was observed exclusively in the first half of the experiment, prior to the intermission, and was abolished in the second half of the experiment.

This pattern of genetic results is particularly intriguing in light of the robust (if transient) potentiation of the interference effects by threat-related distracters observed in the whole sample, collapsing across genotypes. The pattern strongly suggests that the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype modulates susceptibility to cognitive interference in healthy females in general, rather than to cognitive interference produced specifically by threat-related distracters. In this respect, our results are broadly consistent with the view that the 5-HTTLPR genotype may affect susceptibility to environmental influences in general rather than modulating specifically the impact of adverse stimuli (Uher, 2008; Belsky and Pluess, 2009), a trait described as hypervigilance (Homberg and Lesch, 2010). Thus, the S or LG allele is associated with worse behavioral and clinical outcomes in the context of adverse environmental conditions, such as childhood maltreatment or stressful life events, but it can also lead to more favorable outcomes in protective, nurturing environments, relative to the L allele (Caspi et al., 2003; Eley et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2006). Indeed, Roiser et al. (2009) provided elegant evidence for such increased “framing effects” during decision-making, as well as for the corresponding changes in the amygdala-PFC circuitry, in S/S homozygotes compared to LA/LA homozygotes. Although the neurobiological mechanisms involved are likely to be highly complex and thus challenging to fully elucidate, we recently proposed one possible molecular mechanism underlying the interaction of stressors and 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype on the amygdala-VMPFC-dorsal raphe nucleus circuitry and the risk of depression (Jasinska et al., 2012).

Some limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. Although our sample size was sufficiently large to give us high statistical power to detect main and interactive effects of the task, it was relatively small to detect genetic effects. The genetic effects in particular should therefore be considered preliminary until replicated in a larger independent sample. It will also be important to replicate the results in both sexes. Furthermore, cognitive function may also be modulated by other functional variants in the serotonin transporter gene (e.g., serotonin transporter intron 2 polymorphism, STin2; Payton et al., 2005; Sarosi et al., 2008), in other serotonergic genes (e.g., TPH2; Strobel et al., 2007), or in genes involved in gene-gene interactions with the serotonin transporter gene (e.g., BDNF), either in isolation or in interaction with the 5-HTTLPR/rs25531. These effects were unmeasured in our study. Finally, the level of emotion regulation exerted by subjects while performing the task may also modulate performance on tasks which engage emotion-cognition interactions by altering the activity and functional connectivity within the amygdala-PFC circuitry, consistent with recent reports (Schardt et al., 2010; Enge et al., 2011; Lemogne et al., 2011). Therefore, an important goal of future studies will be to measure and manipulate emotion regulation, particularly with respect to serotonin transporter gene effects, to determine to what degree it alters task performance and can compensate for genetic vulnerability to threat reactivity and to cognitive interference.

In conclusion, using a novel threat-distracter MSIT, we demonstrated that threat distracters robustly but transiently potentiate cognitive interference effects, and that 5-HTTLPR/rs25531 genotype modulation of these cognitive interference effects extends to all distracter conditions, irrespective of emotional salience of distracters, in healthy female subjects. These results add to our understanding of the processes through which threat-related distracters affect cognitive processing, and have implications for our understanding of disorders in which threat signals have a detrimental effect on cognition, including depression and anxiety disorders.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Ela Sliwerska for her generous help in carrying out the genetic portion of this study. This research was supported by the Rackham Graduate Student Research Award and the Center for the Education of Women Student Research Award, University of Michigan (Agnes J. Jasinska). When conducting this research, Agnes J. Jasinska was additionally supported by William Orr Dingwall Foundation Fellowship and by Sarah Winans Newman Scholarship from the Center for the Education of Women, University of Michigan.

References

- Barbas H. (2000). Connections underlying the synthesis of cognition, memory, and emotion in primate prefrontal cortices. Brain Res. Bull. 52, 319–330 10.1016/S0361-9230(99)00245-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y., Lamy D., Pergamin L., Bakermans-Kranenburg M. J., van IJzendoorn M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 133, 1–24 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A., Damasio H., Damasio A. R. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 10, 295–307 10.1093/cercor/10.3.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J., Pluess M. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol. Bull. 135, 885–908 10.1037/a0017376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair K. S., Smith B. W., Mitchell D. G., Morton J., Vythilingam M., Pessoa L., Fridberg D., Zametkin A., Sturman D., Nelson E. E., Drevets W. C., Pine D. S., Martin A., Blair R. J. (2007). Modulation of emotion by cognition and cognition by emotion. Neuroimage 35, 430–440 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg J., Henningsson S., Saijo T., Inoue M., Bah J., Westberg L., Lundberg J., Jovanovic H., Andrée B., Nordstrom A. L., Halldin C., Eriksson E., Farde L. (2009). Serotonin transporter genotype is associated with cognitive performance but not regional 5-HT1A receptor binding in humans. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 12, 783–792 10.1017/S1461145708009759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter H. C., Etcoff N. L., Whalen P. J., Kennedy W. A., Rauch S. L., Buckner R. L., Strauss M. M., Hyman S. E., Rosen B. R. (1996). Response and habituation of the human amygdala during visual processing of facial expression. Neuron 17, 875–887 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80219-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G., Shin L. M. (2006). The Multi-Source Interference Task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nat. Protoc. 1, 308–313 10.1038/nprot.2006.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G., Shin L. M., Holmes J., Rosen B. R., Vogt B. A. (2003). The Multi-Source Interference Task: validation study with fMRI in individual subjects. Mol. Psychiatry 8, 60–70 10.1038/sj.mp.4001217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C. S., Botvinick M. M., Cohen J. D. (1999). The contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex to executive processes in cognition. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 49–57 10.1515/REVNEURO.1999.10.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A., Sugden K., Moffitt T. E., Taylor A., Craig I. W., Harrington H., McClay J., Mill J., Martin J., Braithwaite A., Poulton R. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 301, 386–389 10.1126/science.1083968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R., Nakamura K., Daw N. D. (2011). Serotonin and dopamine: unifying affective, activational, and decision functions. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 98–113 10.1038/npp.2010.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R., Roberts A. C., Robbins T. W. (2008). Serotoninergic regulation of emotional and behavioural control processes. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 12, 31–40 10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes S. A., Janelle C. M., Duley A. R. (2005). Emotion and motor control: movement attributes following affective picture processing. J. Mot. Behav. 37, 425–436 10.3200/JMBR.37.6.425-436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes S. A., Tandonnet C., Fujiyama H., Janelle C. M., Cauraugh J. H., Summers J. J. (2009). Emotion and motor preparation: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study of corticospinal motor tract excitability. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 9, 380–388 10.3758/CABN.9.4.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha F. F., Malloy-Diniz L., Lage N. V., Romano-Silva M. A., de Marco L. A., Correa H. (2008). Decision-making impairment is related to serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism in a sample of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav. Brain Res. 195, 159–163 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski U., Konrad C., Kugel H., Zwitserlood P., Domschke K., Schoning S., Ohrmann P., Bauer J., Pyka M., Hohoff C., Zhang W., Baune B. T., Heindel W., Arolt V., Suslow T. (2010). Emotion specific modulation of automatic amygdala responses by 5-HTTLPR genotype. Neuroimage 53, 893–898 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski U., Ohrmann P., Bauer J., Kugel H., Baune B. T., Hohoff C., Kersting A., Arolt V., Heindel W., Deckert J., Suslow T. (2007). Serotonergic genes modulate amygdala activity in major depression. Genes Brain Behav. 6, 672–676 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R. J. (2003). Seven sins in the study of emotion: correctives from affective neuroscience. Brain Cogn. 52, 129–132 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00015-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P., Huys Q. J. (2009). Serotonin in affective control. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 95–126 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desimone R., Duncan J. (1995). Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 193–222 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F., McCarthy G. (2006). Brain systems mediating cognitive interference by emotional distraction. J. Neurosci. 26, 2072–2079 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5042-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eippert F., Veit R., Weiskopf N., Erb M., Birbaumer N., Anders S. (2007). Regulation of emotional responses elicited by threat-related stimuli. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 409–423 10.1002/hbm.20291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P., Friesen W. V. (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press [Google Scholar]

- Eley T. C., Sugden K., Corsico A., Gregory A. M., Sham P., McGuffin P., Plomin R., Craig I. W. (2004). Gene-environment interaction analysis of serotonin system markers with adolescent depression. Mol. Psychiatry 9, 908–915 10.1038/sj.mp.4001546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enge S., Fleischhauer M., Lesch K. P., Strobel A. (2011). On the role of serotonin and effort in voluntary attention: evidence of genetic variation in N1 modulation. Behav. Brain Res. 216, 122–128 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel E., Schlagenhauf F., Sterzer P., Park S. Q., Bermpohl F., Strohle A., Stoy M., Puls I., Hägele C., Wrase J., Büchel C., Heinz A. (2009). 5-HTT genotype effect on prefrontal-amygdala coupling differs between major depression and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 205, 261–271 10.1007/s00213-009-1536-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur R. C., Sara R., Hagendoorn M., Marom O., Hughett P., Macy L., Turner T., Bajcsy R., Posner A., Gur R. E. (2002). A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J. Neurosci. Methods 115, 137–143 10.1016/S0165-0270(02)00006-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A. R., Drabant E. M., Munoz K. E., Kolachana B. S., Mattay V. S., Egan M. F., Weinberger D. R. (2005). A susceptibility gene for affective disorders and the response of the human amygdala. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 146–152 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A. R., Mattay V. S., Tessitore A., Kolachana B., Fera F., Goldman D., Egan M. F., Weinberger D. R. (2002). Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science 297, 400–403 10.1126/science.1071829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley C. A., Phelps E. A. (2010). Changing fear: the neurocircuitry of emotion regulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 136–146 10.1038/npp.2009.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heils A., Teufel A., Petri S., Stober G., Riederer P., Bengel D., Lesch K. P. (1996). Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J. Neurochem. 66, 2621–2624 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A., Braus D. F., Smolka M. N., Wrase J., Puls I., Hermann D., Klein S., Grüsser S. M., Flor H., Schumann G., Mann K., Büchel C. (2005). Amygdala-prefrontal coupling depends on a genetic variation of the serotonin transporter. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 20–21 10.1038/nn1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensler J. G. (2006). Serotonergic modulation of the limbic system. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30, 203–214 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A. J., Bogdan R., Pizzagalli D. A. (2010). Serotonin transporter genotype and action monitoring dysfunction: a possible substrate underlying increased vulnerability to depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 1186–1197 10.1038/npp.2009.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg J. R., Lesch K. P. (2010). Looking on the bright side of serotonin transporter gene variation. Biol. Psychiatry 69, 513–519 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homberg J. R., van den Bos R., den Heijer E., Suer R., Cuppen E. (2008). Serotonin transporter dosage modulates long-term decision-making in rat and human. Neuropharmacology 55, 80–84 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. Z., Lipsky R. H., Zhu G., Akhtar L. A., Taubman J., Greenberg B. D., Xu K., Arnold P. D., Richter M. A., Kennedy J. L., Murphy D. L., Goldman D. (2006). Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78, 815–826 10.1086/503850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinska A. J., Lowry C. A., Burmeister M. (2012). Serotonin transporter gene, stress and raphe-raphe interactions: a molecular mechanism of depression. Trends Neurosci. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs R. A., Telch M. J., Hixon J. G., Evans J. J., Lee H., Knopik V. S., McGeary J. E., Hariri A. R., Beevers C. G. (2012). Genetic and hormonal sensitivity to threat: testing a serotonin transporter genotype x testosterone interaction. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 752–761 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic H., Lundberg J., Karlsson P., Cerin A., Saijo T., Varrone A., Halldin C., Nordström A. L. (2008). Sex differences in the serotonin 1A receptor and serotonin transporter binding in the human brain measured by PET. Neuroimage 39, 1408–1419 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karg K., Burmeister M., Shedden K., Sen S. (2011). The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 444–454 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. S., Kuhn J. W., Vittum J., Prescott C. A., Riley B. (2005). The interaction of stressful life events and a serotonin transporter polymorphism in the prediction of episodes of major depression: a replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 529–535 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. H., Hamann S. (2007). Neural correlates of positive and negative emotion regulation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 19, 776–798 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.5.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S., Smolka M. N., Wrase J., Grusser S. M., Mann K., Braus D. F., Heinz A. (2003). The influence of gender and emotional valence of visual cues on FMRI activation in humans. Pharmacopsychiatry 36(Suppl. 3), S191–S194 10.1055/s-2003-45129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage G. M., Malloy-Diniz L. F., Matos L. O., Bastos M. A., Abrantes S. S., Correa H. (2011). Impulsivity and the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism in a non-clinical sample. PLoS ONE 6, e16927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie N. (2005). Distracted and confused? Selective attention under load. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 9, 75–82 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie N., Ro T., Russell C. (2003). The role of perceptual load in processing distractor faces. Psychol. Sci. 14, 510–515 10.1111/1467-9280.03453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemogne C., Gorwood P., Boni C., Pessiglione M., Lehericy S., Fossati P. (2011). Cognitive appraisal and life stress moderate the effects of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism on amygdala reactivity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 1856–1867 10.1002/hbm.21150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch K. P., Bengel D., Heils A., Sabol S. Z., Greenberg B. D., Petri S., Benjamin J., Müller C. R., Hamer D. H., Murphy D. L. (1996). Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 274, 1527–1531 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K., Hughes B., Chopra S., Gabrieli J. D., Gross J. J., Ochsner K. N. (2010). The neural bases of distraction and reappraisal. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 248–262 10.1162/jocn.2009.21243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. K., Cohen J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 167–202 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell D. G., Luo Q., Mondillo K., Vythilingam M., Finger E. C., Blair R. J. (2008). The interference of operant task performance by emotional distracters: an antagonistic relationship between the amygdala and frontoparietal cortices. Neuroimage 40, 859–868 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. S., Ohman A., Dolan R. J. (1999). A subcortical pathway to the right amygdala mediating “unseen” fear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 1680–1685 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo M. R., Brown S. M., Hariri A. R. (2008). Serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and amygdala activation: a meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 852–857 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman D., Shallice T. (1986). “Attention to action: willed and automatic control of behaviour,” in Consciousness and Self-Regulation: Advances in Research and Theory, Vol. IV, eds Davidson R. J., Schwartz G. E., Shapiro D. E. (New York: Plenum Press; ), 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner K. N., Bunge S. A., Gross J. J., Gabrieli J. D. (2002). Rethinking feelings: an FMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 14, 1215–1229 10.1162/089892902760807212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman A., Mineka S. (2001). Fears, phobias, and preparedness: toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychol. Rev. 108, 483–522 10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet D. M., Hatchwell E., Hajcak G. (2010). Lack of association between the 5-HTTLPR and the error-related negativity (ERN). Biol. Psychol. 85, 504–508 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osinsky R., Reuter M., Kupper Y., Schmitz A., Kozyra E., Alexander N., Hennig J. (2008). Variation in the serotonin transporter gene modulates selective attention to threat. Emotion 8, 584–588 10.1037/a0012826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton A., Gibbons L., Davidson Y., Ollier W., Rabbitt P., Worthington J., Pickles A., Pendleton N., Horan M. (2005). Influence of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms on cognitive decline and cognitive abilities in a nondemented elderly population. Mol. Psychiatry 10, 1133–1139 10.1038/sj.mp.4001733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L., Meyer-Lindenberg A., Drabant E. M., Verchinski B. A., Munoz K. E., Kolachana B. S., Egan M. F., Mattay V. S., Hariri A. R., Weinberger D. R. (2005). 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 828–834 10.1038/nn1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan K. L., Fitzgerald D. A., Nathan P. J., Moore G. J., Uhde T. W., Tancer M. E. (2005). Neural substrates for voluntary suppression of negative affect: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 210–219 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk G. J., Beer J. S. (2006). Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: convergence of rat and human studies. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 723–727 10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees G., Frith C. D., Lavie N. (1997). Modulating irrelevant motion perception by varying attentional load in an unrelated task. Science 278, 1616–1619 10.1126/science.278.5343.1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N., Herrell R., Lehner T., Liang K. Y., Eaves L., Hoh J., Griem A., Kovacs M., Ott J., Merikangas K. R. (2009). Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 301, 2462–2471 10.1001/jama.2009.878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiser J. P., de Martino B., Tan G. C., Kumaran D., Seymour B., Wood N. W., Dolan R. J. (2009). A genetically mediated bias in decision making driven by failure of amygdala control. J. Neurosci. 29, 5985–5991 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0407-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiser J. P., Muller U., Clark L., Sahakian B. J. (2007). The effects of acute tryptophan depletion and serotonin transporter polymorphism on emotional processing in memory and attention. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 10, 449–461 10.1017/S146114570600705X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanski L. M., LeDoux J. E. (1992). Equipotentiality of thalamo-amygdala and thalamo-cortico-amygdala circuits in auditory fear conditioning. J. Neurosci. 12, 4501–4509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarosi A., Gonda X., Balogh G., Domotor E., Szekely A., Hejjas K., Sasvari-Szekely M., Faludi G. (2008). Association of the STin2 polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene with a neurocognitive endophenotype in major depressive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 32, 1667–1672 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardt D. M., Erk S., Nusser C., Nothen M. M., Cichon S., Rietschel M., Treutlein J., Goschke T., Walter H. (2010). Volition diminishes genetically mediated amygdala hyperreactivity. Neuroimage 53, 943–951 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Burmeister M., Ghosh D. (2004). Meta-analysis of the association between a serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and anxiety-related personality traits. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 127B, 85–89 10.1002/ajmg.b.20158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin L. M., Wright C. I., Cannistraro P. A., Wedig M. M., McMullin K., Martis B., Macklin M. L., Lasko N. B., Cavanagh S. R., Krangel T. S., Orr S. P., Pitman R. K., Whalen P. J., Rauch S. L. (2005). A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex responses to overtly presented fearful faces in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 273–281 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel A., Dreisbach G., Muller J., Goschke T., Brocke B., Lesch K. P. (2007). Genetic variation of serotonin function and cognitive control. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 19, 1923–1931 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.12.1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. E., Way B. M., Welch W. T., Hilmert C. J., Lehman B. J., Eisenberger N. I. (2006). Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 671–676 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N., Tanaka J. W., Leon A. C., McCarry T., Nurse M., Hare T. A., Marcus D. J., Westerlund A., Casey B. J., Nelson C. (2009). The NimStim set of facial expressions: judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Res. 168, 242–249 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R. (2008). The implications of gene-environment interactions in depression: will cause inform cure? Mol. Psychiatry 13, 1070–1078 10.1038/mp.2008.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P., Armony J. L., Driver J., Dolan R. J. (2001). Effects of attention and emotion on face processing in the human brain: an event-related fMRI study. Neuron 30, 829–841 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00328-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager T. D., Davidson M. L., Hughes B. L., Lindquist M. A., Ochsner K. N. (2008). Prefrontal-subcortical pathways mediating successful emotion regulation. Neuron 59, 1037–1050 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walderhaug E., Herman A. I., Magnusson A., Morgan M. J., Landro N. I. (2010). The short (S) allele of the serotonin transporter polymorphism and acute tryptophan depletion both increase impulsivity in men. Neurosci. Lett. 473, 208–211 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland J. R., Martin B. J., Kruse M. R., Lesch K. P., Murphy D. L. (2006). Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLC6A4, with a reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and rs25531. Mol. Psychiatry 11, 224–226 10.1038/sj.mp.4001789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen P. J., Rauch S. L., Etcoff N. L., McInerney S. C., Lee M. B., Jenike M. A. (1998). Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J. Neurosci. 18, 411–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrase J., Klein S., Gruesser S. M., Hermann D., Flor H., Mann K., Braus D. F., Heinz A. (2003). Gender differences in the processing of standardized emotional visual stimuli in humans: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci. Lett. 348, 41–45 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00565-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright C. I., Fischer H., Whalen P. J., McInerney S. C., Shin L. M., Rauch S. L. (2001). Differential prefrontal cortex and amygdala habituation to repeatedly presented emotional stimuli. Neuroreport 12, 379–383 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G., Huang Y.-Y., Oquendo M. A., Burke A. K., Hu X.-Z., Brent D. A., Ellis S. P., Goldman D., Mann J. J. (2006). Association of a triallelic serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with stressful life events and severity of depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 1588–1593 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]