Abstract

A new method was here developed for determination of 18O labeling ratios in metabolic oligophosphates, such as ATP, at different phosphoryl moieties (α-, β-, and γ-ATP) using sensitive and rapid electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). The ESI-MS based method for monitoring of 18O/16O exchange was validated with GC-MS and 2D 31P NMR correlation spectroscopy, the current standard methods in labeling studies. Significant correlation was found between isotopomer selective 2D 31P NMR spectroscopy and isotopomer less selective ESI-MS method. Results demonstrate that ESI-MS provides a robust analytical platform for simultaneous determination of levels, 18O-labeling kinetics and turnover rates of α-, β-, and γ-phosphoryls in ATP molecule. Such method is advantageous for large scale dynamic phosphometabolomic profiling of metabolic networks and acquiring information on the status of probed cellular energetic system.

Keywords: 18O isotope labeling, ESI-MS, 31P NMR, ATP, energy metabolism, phosphotransfer networks

Introduction

Comprehensive characterization of metabolic networks and their response to functional load requires quantitative knowledge of complete sets of metabolites, their concentrations and turnover rates [1–5]. Such information enables deduction of intracellular fluxes and dynamic rearrangements in metabolic network modules determining metabolic phenotypes [6–12]. Indeed, metabolites and signaling molecules may display significant changes in turnover rates without noticeable changes in respective concentrations [13–15,9,16,17]. In tracking metabolite turnover rates and performing fluxomic analysis of metabolic networks, stable isotope tracers such as 13C, 18O and 15N have been widely used [17–23,10–12,24]. Among them, 18O isotope has been useful due to its ability to determine phosphoryl-containing metabolite turnover rates and cellular energetic fluxes through phosphotransfer and signal transduction networks [25,23,26,27,9,28–30,15,31,32]. Phosphate-containing metabolites play a dominant role in cellular life [33]. Most of these metabolites are highly polar and their separation and analysis especially of oligophosphates represent a challenge.

The 18O labeling methodology is based on incorporation of the 18O atom from H2 18O into inorganic phosphate (Pi) during ATP hydrolysis and subsequent distribution of 18O-labeled phosphoryls among phosphate-carrying molecules in metabolic networks [27,26,9]. Incorporation of 18O stable isotopes into oligophosphates reflect turnover rates of different phosphoryl moieties and thus its quantification offers a tool to reveal unique information regarding respective enzyme’s activities [25,23,26,27,9,28,34,29]. For instance, the efficiency of intracellular energy transfer in intact cells/tissues catalyzed by adenylate kinase, ATP synthase and ATPase can be deduced from γ- and β-phosphoryl labeling ratio within the ATP molecule [27] while changes in α- phosphoryl of ATP labeling in response adenine nucleotide synthesis de novo [35]. Yet, the activity of other enzymes such as pyrophosphokinase and nucleotidyltransferases [36,9,37] can be monitored only if more subtle analysis is introduced which can differentiate labeling of peripheral versus bridging oxygens in oligophosphates [38].

The incorporation ratio of 18O isotope into oligophosphates containing metabolites can be determined either from 31P NMR spectra, or by GC-MS. GC-MS is a more sensitive method but requires prior metabolite separation, enzymatic transfer of each phosphoryl moiety to glycerol, derivatization and analysis of 18O/16O ratios in glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) [23,31,35,32,9]. The advantage of 18O-assisted 31P NMR spectroscopy is that it permits non-destructive quantification of 18O-labeling ratios of multiple metabolite phosphoryls in a single run; however, compared to GC-MS, it is less sensitive and thus requires a larger amount of sample and a extended analysis time [27,9].

The goal of this work was to apply relatively insensitive, but isotopomer-selective J-decoupled 31P NMR 2D chemical shift correlation spectroscopy to verify the more sensitive, but isotopomer nonselective, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) method. After verification of ESI-MS method for 18O labeling of ATP at different phosphoryl moiety, identical ATP samples were analyzed with both ESI-MS and GC-MS methods to compare the accuracy and sensitivity of ESI-MS. Results demonstrate that ESI-MS provides a suitable analytical platform for simultaneous analysis of 18O/16O exchange in different phosphoryl moieties of oligophosphates, and therefore can be used for determination of phosphoryl turnovers in nucleotide triphosphates involved in different metabolic processes.

Materials and Methods

18O labeling of ATP samples

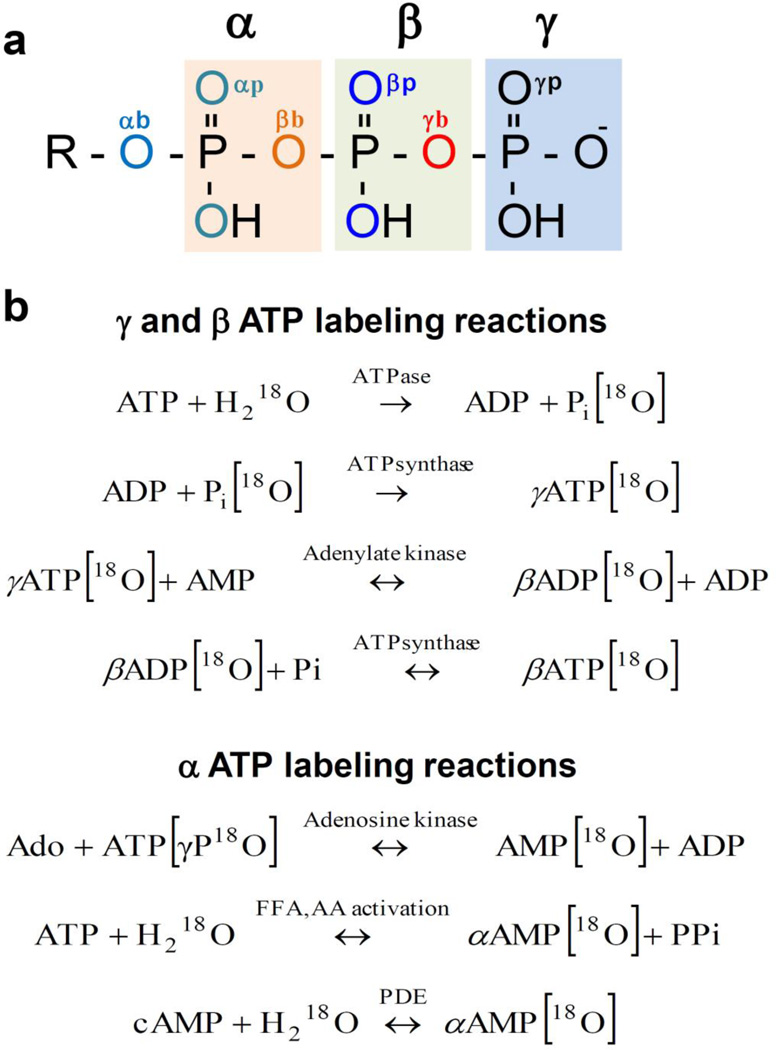

Enzymatic reactions involved in 18O stable isotope metabolic labeling of ATP molecule at different phosphoryl moieties

The oxygen exchange between phosphate and H2[18O] does not occur readily in nature and equilibrium is very slow [39]. Exchange of oxygens in orthophosphate requires use of enzymatic reactions [40]. When tissues or cells are exposed to media containing a known percentage (20–30%) of 18O, H2 18O rapidly equilibrates with cellular water and 18O is incorporated into phosphoryls of ATP proportionally to the rate of enzymatic reactions involved (Fig. 1). First, 18O is incorporated into Pi during each act of ATP hydrolysis by cellular ATPases; subsequent γ-ATP 18O-labeling reflects the activity of ATPsynthase regenerating nascent ATP molecules, while β-ADP/ATP 18O-labeling is exclusively produced by the adenylate kinase catalyzed reaction coupled with ATPsynthase. Labeling of ATP α-phosphoryls is produced by adenosine kinase reaction in adenine nucleotide synthesis de novo, while changes in α-ATP labeling in response to stress or fat/protein load can be induced by phosphodiesterase reaction and cAMP signaling or by FFA and amino acid activation [9,23,34].

Fig. 1.

Differential isotopic 18O/16O substitutions in ATP molecule phosphoryls (a). Oxygen tags: αb – alpha bridge, αp – alpha peripheral, βb – beta bridge, βp – beta peripheral, γb - gamma bridge, γp – gamma peripheral. Enzymatic reactions involved in 18O enrichment of ATP α-, β- and γ-phosphoryls (b). FFA - free fatty acids; AA - amino acids; PDE- phosphodiesterase.

Heart perfusion and 18O phosphoryl labeling

Hearts from heparinized (50 U ip) and anesthetized (75 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium ip) mouse or rat were excised and retrogradely perfused with a 95% O2-5% CO2-saturated Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) solution (in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.3 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 19 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, 11.0 glucose, 0.5 EDTA; 37°C) at a perfusion pressure of 70 mmHg. Hearts were paced at 500 beats/min for mouse and 250 beats/min for rat. Hearts were perfused for 30 min with K-H solution and then subjected to labeling with K-H solution including 30% H2[18O] 30 or 60 s for mice and 10 min for rat; were then immediately freeze-clamped [27,28]. Frozen hearts were pulverized under liquid N2, and extracted in a solution containing 0.6 M HClO4 and 1 mM EDTA. Extracts were neutralized with 2 M KHCO3 and used to determine 18O incorporation into metabolite phosphoryls.

ATP purification

Labeled ATP from perfused heart extracts were purified with HPLC using a Mono Q HR 5/5 ion-exchange column (Pharmacia Biotech) and 1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer (pH 8.8, adjusted with CO2) gradient elution (0.5–90% within 25 min) at 1 mL/min flow rate [9]. The ATP fractions (around 30 min) were collected and dried out using vacuum centrifugation (SpeedVac, Savant) and reconstituted with 100 µl water.

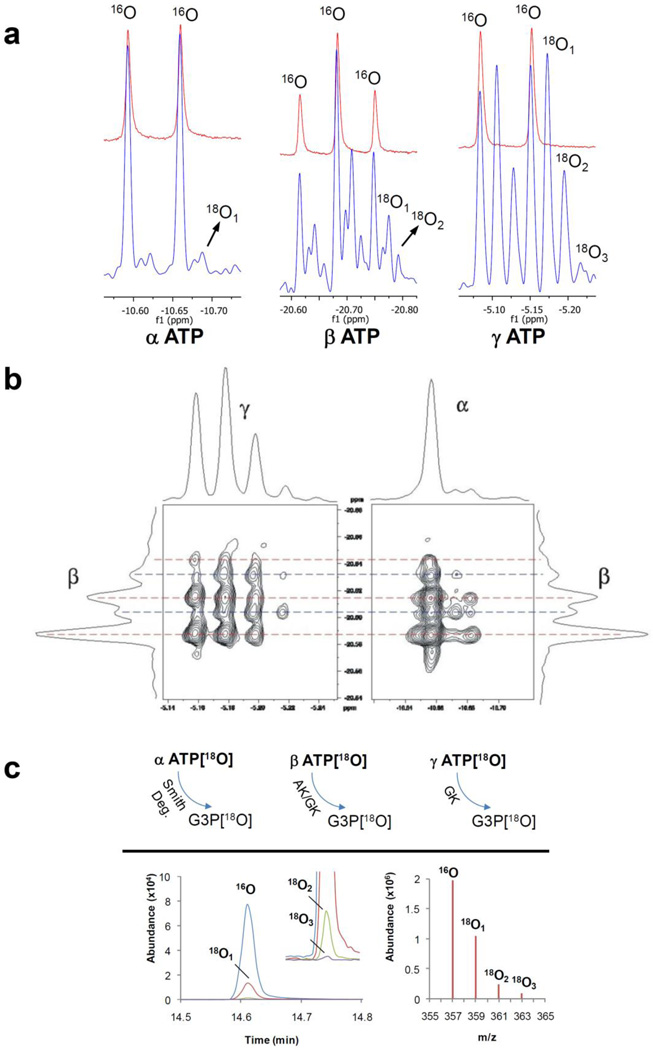

2D 31P NMR spectroscopy

The 283-MHz 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a 700 MHz Avance spectrometer (Spectrospin, Billerica, MA) using an X-channel of indirect detection broadband probe for direct 31P observation. The pulse sequence used for 31P chemical shift correlations of 18O/16O isotopic effects and corresponding experimental details were described previously [38]. The 18O/16O isotope effects are readily visible in high-resolution 31P NMR by 18O induced 31P chemical shifts (Fig. 2a). However, due to scalar couplings in polyphosphates 31P NMR lines are already split into doublets/triplets and 18O/16O isotope exchange effects which introduce additional lines in the 31P NMR spectrum creating a complex pattern of overlapping peaks (Fig. 2a). A better separation of isotopomers was enabled herein by the J-decoupled 31P-31P 2D correlated spectroscopy improved 31P spectra of polyphosphates by eliminating the line splitting due to the scalar coupling, and more importantly, by sorting out correlations between different isotopologues (Fig. 2b) [38].

Fig. 2.

Principles of methods for monitoring 18O enrichment of ATP at different phosphoryl moieties. 1D 31P NMR is based on 18O isotope induced shifts in α-ATP, β-ATP and γ-ATP peaks (Red line - unlabeled ATP and blue line - labeled ATP) (a). 2D 31P NMR uses 18O isotope-induced shifts to separate signals from all isotpologues and isotopomers (b). GC-MS analysis is based on enzymatic transfer of ATP β- and γ-phosphoryls to glycerol and subsequent analyses of 18O labeling of G3P (c). 18O-labeling of α-phosphoryls are analyzed after Smith degradation procedure and generation of G3P (c).

GC-MS

The details of 18O labeling at different phosphoryl moieties have been reported earlier [32]. Briefly, the γ-, β- and α-phosphoryl of purified ATP were transferred to glycerol in a series of enzymatic and chemical reactions (Fig. 2c). First the γ-phosphoryl of ATP was transferred to glycerol by glycerokinase, and then the β-phosphoryl of ATP was transferred to glycerol by a combined catalytic action of adenylate kinase and glycerokinase. Finally the α-phosphoryl of ATP was transferred to glycerol by AMP-deaminase and Smith degradation. Samples that contained phosphoryls of γ-, β- and α-ATP as G3P, were derivatizated using N-methyl-N-trimethyl-silyltrifluoroacetamide+1% trimethylchlorosilane (MSTFA+1% TMCS) (Thermo Fisher) mixture. The 18O-enrichment of phosphoryls in G3P was determined with a Agilent GC-MS operated in the selected ion-monitoring mode (357 m/z for 16O, 359 m/z for 18O1, 361 m/z for 18O2, and 363 m/z for 18O3) (Fig. 2c).

Electron spray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS)

Purified ATP from heart extracts (18O labeled and unlabeled) was 1:1 diluted with 5 mM ammonium acetate in methanol, and then infused continuously at 10 µL min−1 into the ion spray chamber. The system was flushed after each infusion of ATP samples with MS grade water and methanol mixture (1:1, v/v). Experiments were performed using a LTQ-Orbitrap XL MS with Tune Plus software for tuning and Xcalibur 2.0.7 software for data acquisition and processing (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The resolution of the MS was set at 30,000. The Orbitrap mass analyser was operated with a target mass resolution of 30,000 (FWHM as defined at m/z 524) and a scan time of 0.3 s. Samples were analyzed using negative polarity in full scan mode. The mass spectrum from 50 to 700 m/z was recorded. An ATP standard (A2383 Sigma Aldrich), dissolved in MS grade water and diluted 1:1 with 5mM ammonium acetate in methanol, was used to optimize the electrospray ionization conditions. The optimized electrospray ionization settings for ATP were a spray voltage of 4.0 kV, Sheath Gas at 12, Aux Gas at 0, Sweep Gas at 2, Capillary Voltage at −40.0 V, Capillary Temperature set to 275 °C with the Tube lens set at −110.0 V. Fragments at 506, 426 and 346 m/z and their corresponding enriched species 18O1 (parent ion +2 m/z), 18O2 (parent ion +4 m/z), …, and 18On (parent ion +2xn m/z), were analyzed.

Calculation of 18O incorporation in phosphorylated compounds

The exchange of 16O by 18O induces a small, but measurable, chemical shift in 31P NMR spectra and a 2 amu mass increase in mass spectrometry [29,41]. This enabled direct observation of 16O/18O isotope exchange in phosphorylated compounds [32,31,28,27,26,9]. The total degree of isotope exchange (pTot) was the sum of peak areas/intensities (Ik) over all exchange sites (N), weighted by the number of 18O atoms in the respective isotopologues (k), and normalized by the sum of all areas/intensities for a given 31P group of lines:

| (1) |

The cumulative percentage of 18O incorporation was calculated as a ratio of the total degree of 18O exchange in ATP and the total content of 18O in the water used for incubation [27,9]:

| (2) |

ESI-MS data simulation

Populations of ATP 18O isotopologues (wI) in the 10-oxygen site tri-phosphate were calculated (Equation 1, reference [38]) using 18O fractional enrichments of 6 chemically distinct oxygen groups (fk, k ∈ αb, αp, βb, βp, γb, γp) determined by 2D NMR spectroscopy [38]. Corresponding masses of the isotopologues (mI) were calculated by adding the isotopic 18O mass shift (δm = 2.004) of the fractionally enriched oxygen groups as follows:

| (3) |

where m0 is mass of the 18O unlabeled ATP. Alternatively, the calculation was performed using only 3 groups of oxygen atoms (k ∈ α, β, γb), by dropping the distinction between the bridge and peripheral oxygen atoms. The 3-group fractional enrichments were determined as described in “Calculation of 18O incorporation degree in phosphorylated compounds” of this section. These calculations pertain to three ATP fragmental ions which contain adenosine moieties, namely: Adenosine-P3O10, Adenosine-P2O7, Adenosine-PO3, because they are direct descendents of the parental ATP. The only difference between P3O10 and for instance P2O7 calculations is that from each ATP isotopologue a mass content of terminal PO3 group is subtracted.

A stick spectrum was created by summing wI at respective mI. Experimental spectral shapes were simulated by convolution of the stick spectrum with a Gaussian function e−GB2(m−mI)2. The Gaussian broadening (GB) values were constant for all isotopic masses of an ion, exhibiting strong dependence on ionic mass, (GB=m3/2), i.e. GB=105 and 173 for ATP ions of 506 and 346 amu, respectively.

Results

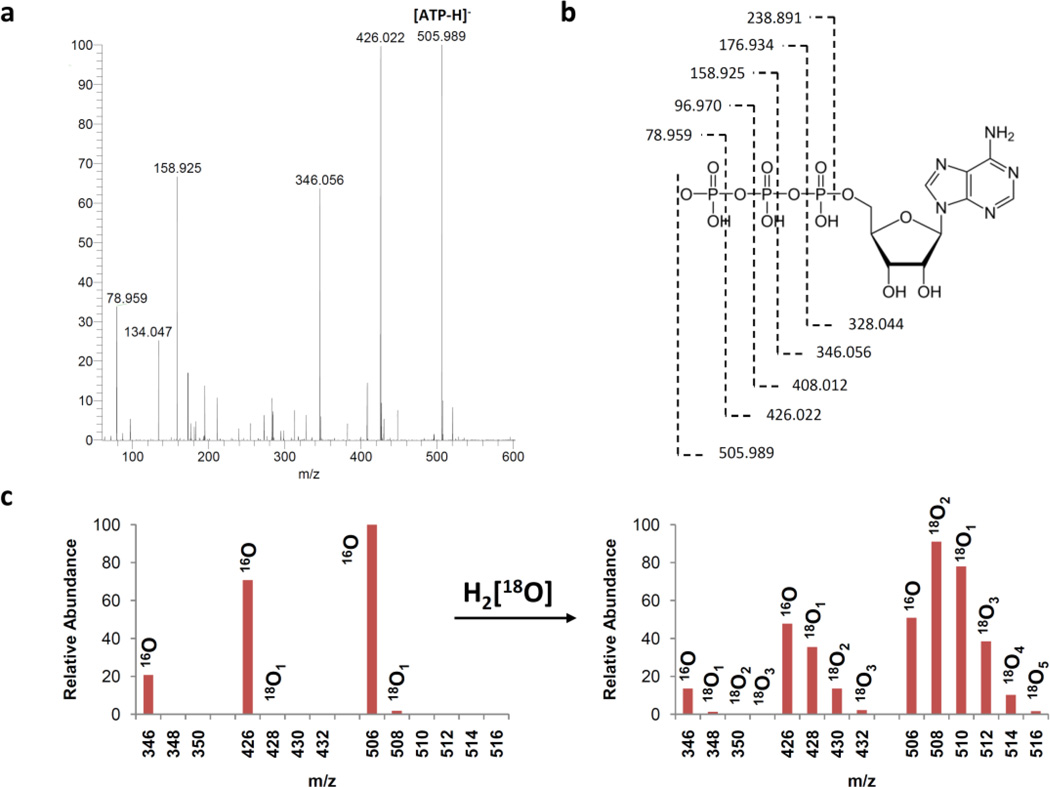

ATP ESI-MS spectra

The ATP samples metabolically labeled with 18O were obtained from hearts perfused with 30% H2 18O in Krebs-Henseleit solution [32,42,38]. After purification using HPLC, the ESI-MS spectra of unlabeled and 18O-labeled ATP were recorded. To calculate the 18O enrichment of phosphoryls in the ATP molecule at the α-, β- and γ- moieties, at least three known fragments that include these phosphoryls were needed. Unlabeled ATP standards produced fragments at 78.986, 158.925, 346.054, 426.020, and 505.986 m/z that correspond to fragments indicated in Fig. 3. After choosing candidate fragments, we have optimized ATP fragmentation to increase intensity of each fragment. First we have looked at infusion solution effect on fragmentation. We were not able to get good fragmentation with MeOH:water (50:50, v/v) mixture, since there were no fragment of α-ATP (346 m/z). After that we have replaced water with a buffered solution in order to change fragmentation and also to eliminate pH changes which may occur in the sample. Using buffered solution we were able to get all fragments required for calculations, however the intensity of the fragments at 346 and 426 m/z were too low. Therefore we have applied in source fragmentation using different collision-induced dissociation (CID) and tube voltage to increase the intensity of fragments. Then we have optimized new parameters, because the more energy generally results in greater fragmentation. However, at higher energies the fragment at 506 m/z were lost. To this end, the optimal yield of selected fragments were found using a methanol 1:5 mM ammonium acetate (1:1, v/v) mixture with −100 mV tube lens voltage and −40 mV CID (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Determination of 18O enrichment of ATP α-, β- and γ-phosphoryls by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). ESI mass spectrum of ATP standard (a), structure and proposed MS fragmentations of ATP (b) and 18O isotopic effects on selected MS fragments of ATP (c); the 16O/18O distribution spectra in phosohoryls of ATP (c, left) was obtained from unlabeled ATP extracted from rat hearts while the right spectra represents 18O metabolically labeled ATP extracted from rat hearts.

The ESI-MS spectra were fitted using initial values for labeling ratios from 2D 31P NMR spectra obtained from the same sample. A strong agreement between simulated and experimental spectra was obtained at fragments of 346, 426 and 506 m/z (Fig. 4). In contrast, fitting fragments at 79 (as γ-PO3) and 159 (as γ-PO3-β-PO3) m/z, resulted in much larger errors which indicates that they originate from more than one position in the ATP molecule. Therefore, we focused on the fragments at 346, 426 and 506 m/z.

Fig. 4.

Simulation of MS spectra for ATP and two fragments (less PO4 group, and less P2O6 group), for labeled samples. The mass distribution was calculated using fractional 18O/16O isotopic enrichments obtained by 2D NMR of the same samples. Digital (open circles) MS spectra of 3 ATP ions (from top to bottom Adenosine-P3O10, Adenosine -P2O7, Adenosine -PO3) and simulated spectral shapes obtained using 3 oxygen groups (red line).

The 18O labeling at different positions of ATP was calculated similar to the total degree of isotope exchange (Eq 1), but with summation over all exchangeable sites in the fragment, n:

| (4) |

Using just three main fragments with 10, 7 and 4 exchange sites (OP atoms), with the exchange degrees, p506, p426, and p346, one obtains degrees of isotope exchange for each phosphate group:

| (5) |

In our case, Fig. 3c, p346(18O) = 0.027, p426(18O) = 0.120 and p506(18O) = 0.166. and from Eq. 4, we found pα = 0.021, pβ = 0.210 and pγ = 0.256 which are in good agreement with enrichments obtained by NMR (pα = 0.03, pβ = 0.23 and pγ = 0.25).

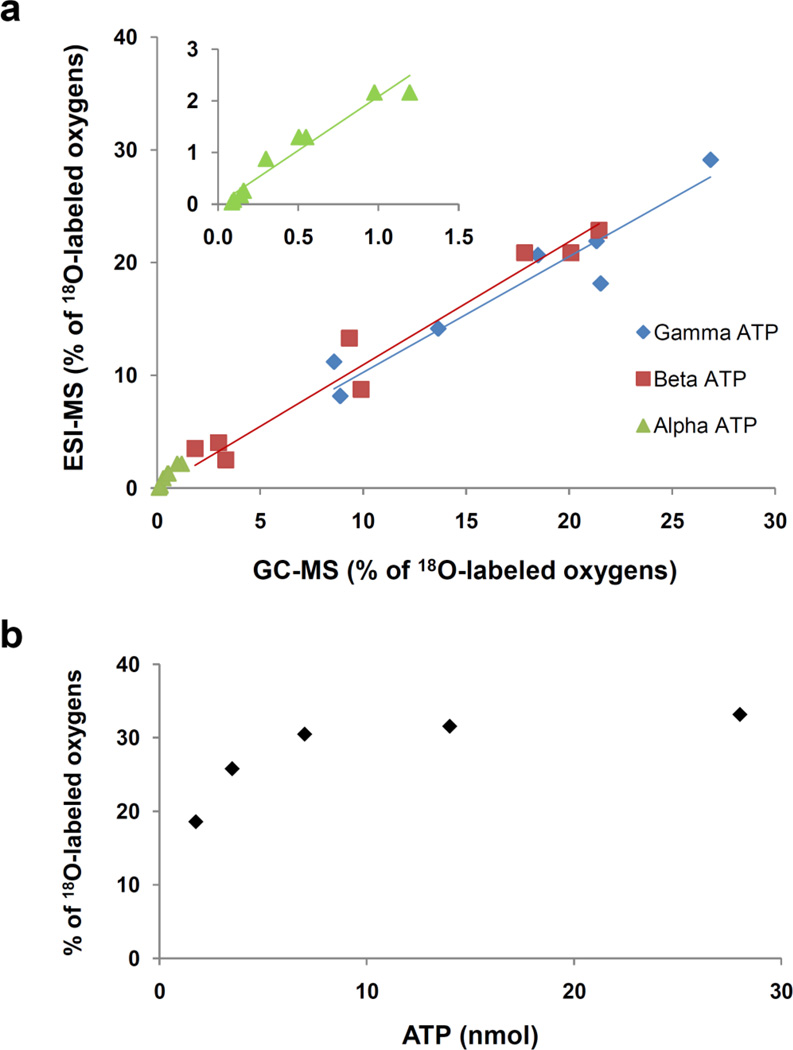

To further verify the accuracy and sensitivity of ESI-MS, nine ATP samples with different 18O enrichments (from mice and rat heart extracts) were analyzed with the GC-MS and ESI-MS methods. The correlation between enrichments at different phosphoryl moiety obtained by GC-MS and ESI-MS are shown in Fig. 5. The slopes were 0.98 for γ-ATP, 1.04 for β-ATP and 2.08 for α-ATP with good linearity and regression coefficients above 0.9. We also tested the repeatability of the ESI-MS with three replicate infusions. In each case the RSD% of the whole ATP 18O labeling was lower than 0.82%. the concentration of ATP in samples varied with the sample origin: very high in heart tissue and very low in whole blood. Therefore, we tested the concentration effects on the labeling ratio of whole ATP. We prepared several dilutions of labeled ATP sample and found that in ESI-MS the labeling ratio became independent from a concentration above 7 nM (Fig. 5b). Thus the optimal amount of sample for labeling ratio determination has been chosen in the middle of curve between 10–20 nM. This recommendation includes both reliability of measurements and sample economy considerations.

Fig. 5.

Correlation of ESI-MS and GC-MS methods on γ-ATP, β-ATP and α-ATP 18O labeling expressed as % of oxygens replaced (a), Sample concentration effect on the accuracy of calculation of cumulative percentage of 18O incorporation into ATP (b).

Finally, the developed method was applied to determine the turnover rates of ATP α-, β- and γ-phosphoryls in mouse heart using the formula: pt(α-ATP) = (1–2−N)× p(H2 18O), where pt(α-ATP) is a fraction of 18O-labeled α-ATP (or β- and γ-) at given time t, N is equal to the number of turnover cycles observed during incubation period and p(H2 18O) is fraction of 18O in media water [43–45]. In mouse hearts ATP α-, β- and γ-phosphoryl turnovers (N) were calculated to be 0.02, 0.20 and 0.57, respectively. This indicates that in mouse heart γ-ATP undergoes about 34 renewal cycles/min, β-ATP about 12 renewal cycles/min and α-ATP about 1 renewal cycle/min.

Discussion

The principal carriers of biological energy are ATP molecules containing three phosphate groups which hydrolysis are coupled with different energy consuming and biosynthetic processes in the cell [46]. In fact, the whole cellular bioenergetic system is built on sequential phosphoryl transfer reactions generating, delivering and distributing high-energy phosphoryls [47]. Cells with high energy turnover are particularly susceptible to insults induced by lack of oxygen or metabolic substrates and their survival depend on the preservation of cellular bioenergetic system and balanced turnover rates [5,48,49].

Stable isotope 18O-labeling is a valuable tool for monitoring turnover rates of phosphoryl-carrying metabolites and phosphotransfer network dynamics in intact tissues. The dynamics of ATP and other nucleotide triphosphate (NTP) α-, β- and γ-phosphoryls carry on array of information regarding energetic, signal transduction and biosynthetic processes of a cell. The turnover rates of α-, β- and γ-phosphoryls of ATP are indicators of metabolic enzyme activities, ATP turnover and phosphotransfer network dynamics in intact tissues [47,9]. Although turnover rates of ATP at α-, β- and γ-phosphoryl moieties have been assessed previously using radioactive and stable isotopes [50,51,44,52,53], here we have developed method for simultaneous determination of turnover rates of three phospate moieties of ATP using ESI-MS. Advantage of such approach is in that that it requires much smaller amount of sample (10 µL) compared to 31P NMR (500 µL) and GC-MS (200 µL) and is much faster and simpler than GC-MS, with long procedures of tedious sample preparation, enzymatic and chemical reactions to clip phosphoryl moieties and derivatization. Comparing ESI-MS with other isotope labeling detection methods in oligophosphates, it is sensitive, fast, simple and safe, especially contrasting to radioactive 32P labeling studies.

A combination of NMR and MS techniques may be useful for a comprehensive evaluation of muscle and cellular bioenergetics and phosphotransfer metabolomics and fluxomics. Even partially discerned isotopologues and isotopomers in 2D 31P NMR enabled accurate determination of the 18O-labeling rates of NMR isotope effect-equivalent oxygen atoms within the tri-phosphoryl moiety. Consequently, the 2D method readily differentiated enrichments of the bridge and peripheral oxygen atoms. For basic analysis, this differentiation might be irrelevant but with the evidence that there are enzymes which affect these oxygen atoms differently, such a differentiation may become increasingly more relevant. Although the 2D method greatly enhanced 18O-assisted 31P NMR spectroscopy it is impractical for serial metabolomic studies because of low sensitivity and as it provide α/β- or β/γ-31Ps correlations, one at a time. On the other hand, MS is much faster and more sensitive but, contrary to NMR the errors in the isotope enrichments for the β- and γ-sites are highly correlated. Namely, these enrichments are obtained as a weighted difference between enrichments of respective ions. Positive errors in p346(18O) tend to increase pβ and decrease pγ, mandating solutions. One is to find more peaks in MS with variable fragmentation (Fig. 3a) or to use a more robust method of peak fitting and simulation instead of simple algebra. Indeed, it is easy to find more MS peaks containing polyphosphate groups (PxOy) but enrichments obtained by their direct use are quite away from the ones found by NMR. This clearly indicates that the same fragment comes from different positions in the ATP molecule. For example, the ion P2O6 (158.925 m/z) may originate either from α–β or β–γ fragments, created by different fragmentation paths. Thus, it is impossible to use these ions directly for labeling calculation, but by taking into account the isotope enrichment known independently, e.g., from NMR, the fraction of α–β and β–γ could be calculated, and subsequently used for analysis of samples with unknown enrichment. In this way, the same fitting procedure used to analyze 2D spectra [38] could greatly improve the accuracy of the MS method. Indeed, using only three fragments that contain adenosine of ATP, the fitting procedure that includes all peak intensity simultaneously resulted in slightly different, but noticeable, differences between the peripheral and bridge beta oxygen atoms (Fig. 4). This actually means that the MS spectra are also sensitive to the isotopomer distribution. This may appear surprising at first sight, but can be accounted as different isotopomers are present in each ion with different statistical weights. We believe that a proper calibration of MS spectra, based on NMR analysis of the same sample, can ultimately enable MS to determine isotope enrichment efficiently and reliably for the bridge and peripheral oxygen atoms. Whereas a very high correlation between GC-MS and ESI-MS for γ and β labeling is observed (regression coefficients and slopes of γ- and β- enrichments close to each other), poor correlation is observed for α ATP. This could be explained by very low labeling at α-position as well as lower sensitivity and derivatization effects in GC-MS.

The possibility of 18O/16O ion exchange in the ESI source or during to sample preparation can be ignored, since the oxygen exchange between phosphate and H2[18O] does not occur readily in nature [39,40] and under ionization conditions present in ESI-MS [54]. Moreover, the possibility of gas phase ion reaction needs to be considered too. Here, the Adenosine-P3O10 used in the study was purified, therefore the source of Adenosine - P2O7 and Adenosine -PO3 was only be the Adenosine-P3O10 using in source fragmentation. Good correlation of LC/MS data with GC-MS and 2D 31P NMR indicated that the possibility of gas phase ion reactions is negligible.

The labeling degree in ATP depends on the incubation time and the fraction of 18O in the media water. However, correct calculation of the labeling degree depends on the concentration, because the signals of the fragments cannot be distinguished from noise at the low concentration even at high enrichment ratio. Therefore precautions must be given to labeling calculation. To determine correct enrichment of ATP, at least three degree of 18O labeling (the fragments at 512 m/z, 18O3) must be observed. In our cases, we found that the labeling ratio becomes independent from concentration above 7 nmol (Fig. 5b) in 30% of 18O in media water for 10 min labeling.

Determined here accurate α-, β- and γ-phosphoryl turnover rates of ATP in mouse hearts indicate that α-ATP turns over only once every minute, while β- and γ-ATPs are turning over 12 and 34 cycles per minute, respectively. Literature data regarding labeling and turnovers of ATP α-, β- and γ-phosphoryls is rather sparse. In comparison, human and rat heart γ-ATP turnovers are 6 and 20 cycles per minute, respectively [55,9]. Labeling data of ATP with radioactive 32P in Escherichia coli indicate that both β- and γ-ATPs undergo about 17 turnover cycles per minute while α-ATP turns over only 1 cycle per minute [52]. From similar labeling study calculated ATP turnover rates in rabbit hearts are about 25 cycles per minute for β- and γ-ATPs and 0.25 cycles per minute for α-ATP [44]. Thus, ESI-MS technology provides a robust and reliable method for monitoring turnover rates of phosphoryls in ATP with short analysis time and high sensitivity.

Conclusion

Knowledge of the dynamics of ATP at α-, β- and γ-phosphoryl moieties and those in other NTPs provides valuable information about energetic and biosynthetic processes in the cell. Here, we developed and validated the applicability of the robust ESI-MS method for determining fractional stable isotope enrichment within separate groups of mono-, di- or tri-phosphates. The advantage of the ESI-MS over the 1D 31P NMR and GC-MS was a shorter time and higher sensitivity for detection and quantification of 18O/16O exchange in individual phosphate moieties. In combination with LC, this method permits analysis of multiple mono-, di- and tri- phosphates at the same time without any pre-purification steps. This allows simultaneous determination of almost all mono-, di- and tri-phosphate 18O-labeling ratios and turnover rates in intact tissues. Thus ESI-MS, calibrated by 2D 31P NMR, provides a suitable analytical platform for dynamic phosphometabo-lomic profiling of tissue energy metabolism. The ESI-MS method developed here can be applied for determination of labeling ratios of other biologically important NTP (GTP, ITP, UTP and CTP) and di-phosphates (ADP, GDP, UDP and CDP) and inositiol oligophosphates (IP3, IP5). Especially since concentrations of these triphosphates are much lower than ATP and have similar chemical shifts with ATP in 31P NMR spectra. Therefore it is not possible to separate and determine 18O-labeling of other NTPs in the presence of ATP using 31P NMR. Thus ESI-MS method can be applied to analyze 18O-labeling and turnover of multiple oligophosphates at very low concentration in biological samples.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mai T. Persson, Godfrey C. Ford and Linda M. Benson for their technical assistance with ESI-MS analyses. This work has been supported by NIH, Marriott Heart Disease Research Program, Marriott Foundation and Mayo Clinic. This work was supported by NIH/NCRR CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024150.

Abbreviations

- NTP

nucleoside triphosphate

- G3P

glycerol 3-phosphate

- FFA

free fatty acids

- AA

amino acids

References

- 1.Saks V, Dzeja P, Schlattner U, Vendelin M, Terzic A, Wallimann T. Cardiac system bioenergetics: metabolic basis of the Frank-Starling law. Journal of Physiology-London. 2006;571:253–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.101444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrell DK, Terzic A. Network Systems Biology for Drug Discovery. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;88(1):120–125. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dzeja PP, Chung S, Faustino RS, Behfar A, Terzic A. Developmental Enhancement of Adenylate Kinase-AMPK Metabolic Signaling Axis Supports Stem Cell Cardiac Differentiation. Plos One. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019300. doi:ARTN e19300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dzeja PP, Bortolon R, Perez-Terzic C, Holmuhamedov EL, Terzic A. Energetic communication between mitochondria and nucleus directed by catalyzed phosphotransfer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(15):10156–10161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152259999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dzeja PP, Hoyer K, Tian R, Zhang S, Nemutlu E, Spindler M, Ingwall JS. Rearrangement of energetic and substrate utilization networks compensate for chronic myocardial creatine kinase deficiency. Journal of Physiology-London. 2011;589(21):5193–5211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen E, Terzic A, Wieringa B, Dzeja PP. Impaired intracellular energetic communication in muscles from creatine kinase and adenylate kinase (M-CK/AK1) double knockout mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(33):30441–30449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzeja P, Terzic A. Adenylate Kinase and AMP Signaling Networks: Metabolic Monitoring, Signal Communication and Body Energy Sensing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2009;10(4):1729–1772. doi: 10.3390/ijms10041729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen E, de Groof A, Wijers M, Fransen J, Dzeja PP, Terzic A, Wieringa B. Adenylate kinase 1 deficiency induces molecular and structural adaptations to support muscle energy metabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(15):12937–12945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pucar D, Dzeja PP, Bast P, Juranic N, Macura S, Terzic A. Cellular energetics in the preconditioned state - Protective role for phosphotransfer reactions captured by O-18-assisted P-31 NMR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(48):44812–44819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincent G, Khairallah M, Bouchard B, Des Rosiers C. Metabolic phenotyping of the diseased rat heart using C-13-substrates and ex vivo perfusion in the working mode. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;242(1–2):89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, Bian F, Chaudhuri P, Mao XA, Brunengraber H, Yu X. Delineation of substrate selection and anaplerosis in tricarboxylic acid cycle of the heart by (13)C NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. Nmr in Biomedicine. 2011;24(2):176–187. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pound KM, Sorokina N, Ballal K, Berkich DA, Fasano M, LaNoue KF, Taegtmeyer H, O'Donnell JM, Lewandowski ED. Substrate-Enzyme Competition Attenuates Upregulated Anaplerotic Flux Through Malic Enzyme in Hypertrophied Rat Heart and Restores Triacylglyceride Content Attenuating Upregulated Anaplerosis in Hypertrophy. Circulation Research. 2009;104(6):805–812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruger NJ, Ratcliffe RG. Insights into plant metabolic networks from steady-state metabolic flux analysis. Biochimie. 2009;91(6):697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul Lee WN, Wahjudi PN, Xu J, Go VL. Tracer-based metabolomics: concepts and practices. Clinical biochemistry. 2010;43(16–17):1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen E, Dzeja PP, Oerlemans F, Simonetti AW, Heerschap A, de Haan A, Rush PS, Terjung RR, Wieringa B, Terzic A. Adenylate kinase 1 gene deletion disrupts muscle energetic economy despite metabolic rearrangement. EMBO J. 2000;19(23):6371–6381. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin JL, Des Rosiers C. Applications of metabolomics and proteomics to the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: lessons from downstream of the transcriptome. Genome Med. 2009;1(3):1–11. doi: 10.1186/gm32. doi:gm32 [pii] 10.1186/gm32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelleher JK. Flux estimation using isotopic tracers: common ground for metabolic physiology and metabolic engineering. Metabolic engineering. 2001;3(2):100–110. doi: 10.1006/mben.2001.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Y, Pingitore F, Mukhopadhyay A, Phan R, Hazen TC, Keasling JD. Pathway confirmation and flux analysis of central metabolic pathways in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Journal of Bacteriology. 2007;189(3):940–949. doi: 10.1128/JB.00948-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamboni N. (13)C metabolic flux analysis in complex systems. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2011;22(1):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee WNP, Wahjudi PN, Xu J, Go VL. Tracer-based metabolomics: Concepts and practices. Clinical biochemistry. 2010;43(16–17):1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane AN, Fan TWM, Higashi RM. Isotopomer-based metabolomic analysis by NMR and mass Spectrometry. Biophysical Tools for Biologists: Vol 1 in Vitro Techniques. 2008;84:541. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84018-0. -+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauer U. Metabolic networks in motion: C-13-based flux analysis. Molecular Systems Biology. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100109. doi:Artn 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeleznikar RJ, Goldberg ND. Kinetics and compartmentation of energy metabolism in intact skeletal muscle determined from 18O labeling of metabolite phosphoryls. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(23):15110–15119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malloy CR, Merritt ME. Dean Sherry A Could 13C MRI assist clinical decision-making for patients with heart disease? Nmr in Biomedicine. 24(8):973–979. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stempel KE, Boyer PD. Refinement in oxygen-18 methodology for the study of phosphorylation mechanisms. Methods in Enzymology. 1986;VOL. 126:618–639. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)26065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pucar D, Janssen E, Dzeja PP, Juranic N, Macura S, Wieringa B, Terzic A. Compromised energetics in the adenylate kinase AK1 gene knockout heart under metabolic stress. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(52):41424–41429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007903200. M007903200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pucar D, Dzeja PP, Bast P, Gumina RJ, Drahl C, Lim L, Juranic N, Macura S, Terzic A. Mapping hypoxia-induced bioenergetic rearrangements and metabolic signaling by O-18-assisted P-31 NMR and H-1 NMR spectroscopy. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2004;256(1–2):281–289. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009875.30308.7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pucar D, Bast P, Gumina RJ, Lim L, Drahl C, Juranic N, Macura S, Janssen E, Wieringa B, Terzic A, Dzeja PP. Adenylate kinase AK1 knockout heart: energetics and functional performance under ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283(2):H776–H782. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00116.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn M, Hu A. Isotopic (18O) shift in 31P nuclear magnetic resonance applied to a study of enzyme-catalyzed phosphate--phosphate exchange and phosphate (oxygen)--water exchange reactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75(1):200–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeleznikar RJ, Dzeja PP, Goldberg ND. Adenylate kinase-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer couples ATP utilization with its generation by glycolysis in intact muscle. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(13):7311–7319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dzeja PP, Zeleznikar RJ, Goldberg ND. Suppression of creatine kinase-catalyzed Phosphotransfer results in increased phosphoryl transfer by adenylate kinase in intact skeletal muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(22):12847–12851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dzeja PP, Vitkevicius KT, Redfield MM, Burnett JC, Terzic A. Adenylate kinase-catalyzed phosphotransfer in the myocardium - Increased contribution in heart failure. Circulation Research. 1999;84(10):1137–1143. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westheimer FH. Why nature chose phosphates. Science. 1987;235(4793):1173–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.2434996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawis SM, Walseth TF, Deeg MA, Heyman RA, Graeff RM, Goldberg ND. Adenosine triphosphate utilization rates and metabolic pool sizes in intact cells measured by transfer of 18O from water. Biophys J. 1989;55(1):79–99. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82782-1. [pii] 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82782-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeleznikar RJ, Heyman RA, Graeff RM, Walseth TF, Dawis SM, Butz EA, Goldberg ND. Evidence for compartmentalized adenylate kinase catalysis serving a high energy phosphoryl transfer function in rat skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(1):300–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knowles JR. Enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:877–919. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber DJ, Bhatnagar SK, Bullions LC, Bessman MJ, Mildvan AS. NMR and isotopic exchange studies of the site of bond cleavage in the MutT reaction. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(24):16939–16942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juranic N, Nemutlu E, Zhang S, Dzeja P, Terzic A, Macura S. (31)P NMR correlation maps of (18)O/(16)O chemical shift isotopic effects for phosphometabolite labeling studies. Journal of Biomolecular Nmr. 2011;50(3):237–245. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9515-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blake RE, ONeil JR, Garcia GA. Oxygen isotope systematics of biologically mediated reactions of phosphate. 1. Microbial degradation of organophosphorus compounds. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta. 1997;61(20):4411–4422. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolodny Y, Luz B, Navon O. Oxygen Isotope Variations in Phosphate of Biogenic Apatites. 1. Fish Bone Apatite - Rechecking the Rules of the Game. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1983;64(3):398–404. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohn M, Hu A. Isotopic 18O Shifts in 31P NMR of Adenosine Nucleotides Synthesized with 18O in Various Positions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1980;103:913–916. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pucar D, Janssen E, Dzeja PP, Juranic N, Macura S, Wieringa B, Terzic A. Compromised energetics in the adenylate kinase AK1 gene knockout heart under metabolic stress. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(52):41424–41429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karl DM, Bossard P. Measurement of Microbial Nucleic Acid Synthesis and Specific Growth Rate by PO(4) and [H]Adenine: Field Comparison. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50(3):706–709. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.3.706-709.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi A. 32P labelling of the nucleotides in alpha-position in the rabbit heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1975;7(12):891–906. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(75)90150-9. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zilversmit DB, Entenman C, Fishler MC. On the Calculation of "Turnover Time" and "Turnover Rate" from Experiments Involving the Use of Labeling Agents. The Journal of general physiology. 1943;26(3):325–331. doi: 10.1085/jgp.26.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ingwall JS. ATP and the Heart. vol 11. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dzeja PP, Terzic A. Phosphotransfer networks and cellular energetics. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2003;206(12):2039–2047. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiong QA, Du F, Zhu XH, Zhang PY, Suntharalingam P, Ippolito J, Kamdar FD, Chen W, Zhang JY. ATP Production Rate via Creatine Kinase or ATP Synthase In Vivo A Novel Superfast Magnetization Saturation Transfer Method. Circulation Research. 2011;108(6):653–U265. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ingwall JS, Shen WQ. On energy circuits in the failing myocardium. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2010;12(12):1268–1270. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levinson C, Gordon ED., Jr Phosphorus incorporation in the Ehrlich ascites tumor cell. J Cell Physiol. 1971;78(2):257–264. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040780213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karl DM, Bossard P. Measurement and significance of ATP and adenine nucleotide pool turnover in microbial cells and environmental samples. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 1985;3(3–4):125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lutkenhaus J, Ryan J, Konrad M. Kinetics of phosphate incorporation into adenosine triphosphate and guanosine triphosphate in bacteria. Journal of Bacteriology. 1973;116(3):1113–1123. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.3.1113-1123.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zahn D, Klinger R, Frunder H. Enzymic flux rates within the mononucleotides of the mouse liver. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1969;11(3):549–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1969.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvarez R, Evans LA, Milham P, Wilson MA. Analysis of oxygen-18 in orthophosphate by electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2000;203(1–3):177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Opie LH, Opie L. The heart: physiology, from cell to circulation. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]