Abstract

We previously demonstrated that 3rd ventricular (3V) neuropeptide Y (NPY) or agouti-related protein (AgRP) injection potently stimulates food foraging/hoarding/intake in Siberian hamsters. Because NPY and AgRP are highly colocalized in arcuate nucleus neurons in this and other species, we tested whether subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP coinjected into the 3V stimulates food foraging, hoarding, and intake, and/or neural activation [c-Fos immunoreactivity (c-Fos-ir)] in hamsters housed in a foraging/hoarding apparatus. In the behavioral experiment, each hamster received four 3V treatments by using subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP for all behaviors: 1) NPY, 2) AgRP, 3) NPY+AgRP, and 4) saline with a 7-day washout period between treatments. Food foraging, intake, and hoarding were measured 1, 2, 4, and 24 h and 2 and 3 days postinjection. Only when NPY and AgRP were coinjected was food intake and hoarding increased. After identical treatment in separate animals, c-Fos-ir was assessed at 90 min and 14 h postinjection, times when food intake (0–1 h) and hoarding (4–24 h) were uniquely stimulated. c-Fos-ir was increased in several hypothalamic nuclei previously shown to be involved in ingestive behaviors and the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), but only in NPY+AgRP-treated animals (90 min and 14 h: magno- and parvocellular regions of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and perifornical area; 14 h only: CeA and sub-zona incerta). These results suggest that NPY and AgRP interact to stimulate food hoarding and intake at distinct times, perhaps released as a cocktail naturally with food deprivation to stimulate these behaviors.

Keywords: c-fos, Siberian hamster, hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, perifornical area, central nucleus of the amygdala, sub-zona incerta

in 1918, wallace craig (12) broadly dichotomized behaviors into responses that bring animals in contact with a goal object (appetitive behaviors), here food, that include foraging and hoarding or the culmination of that acquisition (consummatory behaviors), here eating. Most animals forage and hoard food, including humans (for review see Ref. 50) who, in industrialized nations, seek food at stores and store food in refrigerators, freezers, pantries, and cupboards (hoard). Food hoarding may have evolved as one way to help assure energy availability under conditions where the presence of food is variable (e.g., seasonal changes, increased predation pressures) in addition to internal energy stored as body fat.

Although much has been discovered about the mechanisms underlying consummatory ingestive behaviors from studies of laboratory rats and mice, most studies typically are not designed to measure the appetitive phase of ingestive behavior (for review see Ref. 7). Therefore, we know comparatively little about the mechanisms underlying appetitive ingestive behaviors in rodents compared with consummatory ingestive behavior. Likely contributing to the dearth of information on appetitive behavior mechanisms is the lack of food hoarding by the wild counterparts to laboratory rats and mice (for review see Refs. 7 and 33); those animals eat food at the source or carry some in their mouth to a nearby safe locale, where they eat it, but not to their burrows. Thus, laboratory rats and mice perhaps are best suited for studies of consummatory ingestive behaviors and not appetitive ingestive behaviors, at least in terms of food hoarding.

By contrast with laboratory rats and mice, Siberian hamsters (Phodopus sungorus) naturally hoard food in nature (53) and in the laboratory (for review see Refs. 5 and 7). Siberian hamsters have large cheek pouches that allow them to transport considerable amounts of food from its source to their burrows, somewhat analogous to humans carrying food using grocery bags and car trunks; thus, it is not surprising that food hoarding is an important component of their ingestive behavior repertoire (for review see Ref. 7). Therefore, combining the study of Siberian hamsters with our foraging/hoarding apparatus (see Ref. 15 for complete description and one in brief below), we are in a unique position to more inclusively study both appetitive and consummatory ingestive behaviors.

The most reliable stimulator of foraging and/or food hoarding across species is food deprivation (for a review see Ref. 7). In Siberian hamsters, food deprivation-refeeding results in prolonged increases in food foraging and hoarding, but not food intake, a disassociation similar to humans (21, 27, 38, 39), thereby permitting the unraveling of the mechanisms underlying appetitive and consummatory ingestive behaviors that often are inextricably intertwined (for review see Refs. 7 and 33). We have successfully tested the role of several endogenous signals thought to be involved in food deprivation-induced increases in food intake seen by laboratory rats and mice by using Siberian hamsters housed in our foraging/hoarding apparatus. These studies resulted in marked increases in food hoarding with much lesser increases in food intake [i.e., ghrelin (30–32), neuropeptide Y (NPY; 13, 18, 32) and agouti-related protein (AgRP; 17)].

The arcuate nucleus (ARC) has received considerable attention as a major component of the distributed system that controls food intake. One neurochemical phenotype of these neurons is a high colocalization of NPY and AgRP (25), a colocalization that also occurs in Siberian hamsters (40). In Siberian hamsters, as in laboratory rats and mice [e.g., (47)], food deprivation increases NPY and AgRP gene expression (45). Potential release of both orexigenic peptides in vivo is suggested by the co-release of NPY and AgRP in hypothalamic explants after exposure to cocaine and amphetamine-related transcript (20), as well the presence of neurons within the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVH) that receive ARC neural projections consisting of fibers coexpressing NPY- and AgRP-immunoreactivity (11). In addition, electrophysiological measures of individual PVH neurons demonstrate a common site of action for NPY and AgRP (11), the latter primarily or exclusively being an antagonist of the melanocortin 3/4 receptor [MC 3/4R; (10)]. Collectively, these data point to a possible co-release and interaction of NPY and AgRP under conditions such as food deprivation.

Both AgRP and NPY appear to be involved with appetitive ingestive behaviors as well as their well-established effects on consummatory ingestive behavior. That is, central [3rd ventricular (3V)] injection of NPY (18) or AgRP (17) and parenchymal injection of NPY into the PVH or perifornical area (pFA; 13) increase foraging and especially food hoarding by Siberian hamsters along with smaller increases in food intake, with the hoarding levels similar in magnitude to that occurring with food deprivation-refeeding in this species [e.g., (4, 14, 16)]. Interestingly, NPY and AgRP differ in their temporal pattern of increasing food hoarding with NPY, causing early increases (1–2 day, especially the first 24 h) and AgRP causing a more prolonged increase [3–7 days; (13, 17, 18)].

We are aware of only one study in laboratory rodents where a possible interaction of NPY and AgRP was tested. Specifically, PVH coinjection of a suprathreshold dose of NPY with a subthreshold dose of AgRP increased food intake above that of AgRP alone (54). Thus, given the colocalization and possible co-release of NPY and AgRP (20), both of their stimulatory effects on ingestive behavior, and apparent interaction in the PVH to stimulate food intake (54), it is possible that the two interact to stimulate appetitive (food foraging, hoarding) as well as consummatory (food intake) ingestive behaviors. Therefore, we conducted two experiments to address this hypothesis. In experiment 1 we asked: Do subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP interact to increase ingestive behavior? In a second supportive functional neuroanatomical experiment to the first, we asked: Do subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP interact to activate central neuronal activity? In terms of the latter study, we assessed c-Fos immunoreactivity (c-Fos-ir), an accepted indicator of neural activation (28).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Siberian hamsters, ∼2.5–3.5 mo old and weighing 35–45 g were obtained from our breeding colony. Hamsters were group housed and raised in a long-day photoperiod (16:8-h light-dark cycle; light onset at 0200) from birth until use in the experiments. Food (5001; Purina, St. Louis, MO) and tap water were available ad libitum unless otherwise indicated. Room temperature was maintained at 21 ± 2.0°C. All procedures were approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are in accordance with Public Health Service and United States Department of Agriculture guidelines.

Cannula Implantation, Injections, and Verification

Cannulae were stereotaxically implanted into the 3V under isoflurane (Aerrane; Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) inhalation anesthesia as previously described (13). Briefly, each hamster had its head shaved and skull exposed. A guide cannula (26-gauge stainless steel; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) was lowered stereotaxically [coordinates: level skull, anterior-posterior from bregma 0 mm, medial-lateral from midsaggital sinus 0 mm (the sinus was moved to avoid damage due to lowering of the cannula), and dorsal-ventral from the top of the skull −5.0 mm] targeted for placement just above the 3V. The guide cannulae were secured to the skull using cyanoacrylate ester gel, 3/16 mm jeweler's screws, and dental acrylic. A removable obturator sealed the opening in the guide cannulae throughout the experiment except during 3V injections. Hamsters received buprenorphine (0.2 mg/kg body mass) at 12 and 24 h postsurgery to minimize surgical discomfort and an apple slice to facilitate food and water intake. A 2-wk postsurgery recovery period occurred where the hamsters were housed in shoebox cages.

One week before each test day, each animal was mock-injected daily, where the obturator was removed, and the animal was lightly restrained for one minute to acclimate the animal to the intraventricular injection procedure. On test days, an inner cannula (33-gauge stainless steel; Plastics One) extending 0.5 mm beyond the guide cannula was connected to a Hamilton syringe via PE-20 tubing and inserted into the guide cannula. All hamsters were injected with 400 nl total volume of neurochemical and/or vehicle at light offset. Animals were lightly restrained by hand during the ∼30-s injection, and the injection needle remained in place ∼30 s before withdrawal, as we have done previously (13).

Following the last behavioral test in experiment 1, an injection of 400 nl of bromophenol blue dye was given to confirm placement of the cannula in the third ventricle. The animals were then given an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg), transcardially perfused with 100 ml of heparinized saline followed by 125 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH = 7.4. The brains were removed and then postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for a minimum of 2 days, followed by 30% sucrose for at least 2 days, replacing the sucrose solution after 24 h. Each brain was sliced manually (80 μm) for cannula verification. Cannulae were considered to be located in the 3V if the dye was visible in any part of this ventricle as revealed by light microscopy. A similar procedure was carried out for experiment 2, except no dye was injected. Site verification was confirmed by examining the cannula tract, and tissue was sliced at 35 μm and then stored in PBS at 5°C until tissue processing (see below). Only the data from animals with confirmed 3V cannulae placements were included in the analyses. No cannula was dislodged across either study.

Foraging and Hoarding Apparatus

Hamsters were acclimated for 1 wk, before and after cannula implantation, in specially designed foraging/hoarding apparatuses as previously described (15) that would serve as their housing for the duration of the experiment. More specifically, two cages were connected with polyvinylchloride tubing system (38.1 mm ID and ∼1.52 m long) with corners and straight-aways for vertical and horizontal climbs. The top, or food cage, was 456 × 234 × 200 mm (length × width × height) and equipped with a water bottle, running wheel (524 mm circumference), and food pellet dispenser. The diet (75 mg pellets, Bio-Serve, Frenchtown, NJ) and tap water were available ad libitum, unless otherwise noted. The bottom, or burrow cage, was 290 × 180 × 130 mm (length × width × height) and contained Alpha-Dri (Specialty Papers, Kalamazoo, MI) bedding and one cotton nestlet (Ancare, Belmore, NY). The bottom cage was opaque and covered to simulate the darkness of a burrow. Wheel revolutions were counted by using a magnetic detection system and monitored by a computer-based hardware-software program (Med Associates, Georgia, VT). Hamsters were first trained in these apparatuses and then received the 3V cannula, as previously described (13) and described here in brief.

We used a wheel-running training regimen that eases the hamsters into their foraging efforts without large changes in body mass or food intake. Specifically, hamsters were given free access to food pellets for 2 days while they adapted to the running wheel. In addition to the free food, a 75-mg food pellet was dispensed upon completion of every 10 wheel revolutions. On the third day, the free food condition was replaced by a response-contingent condition where only every 10 wheel revolutions triggered the delivery of a pellet. This condition was in effect for 5 days during which time body mass, food intake, food hoarding, wheel revolutions, and pellets earned (foraging) were measured daily. At the end of this acclimation period (7 days total), animals were removed from the foraging apparatuses and temporarily housed in shoebox cages where the same food pellets were available ad libitum with no foraging requirements. Guide cannulae were then surgically implanted in these hamsters (see above for details). Following the 2-wk postsurgical recovery period, all hamsters were returned to the hoarding/foraging apparatus and retrained to the following schedule: 2 days for adaptation with free access to food pellets paired with 10 wheel revolutions/pellet and then 5 days of 10 revolutions/pellet only, as above.

Measurement of Foraging, Food Hoarding, and Food Intake

Foraging (pellets earned) was defined as the number of pellets delivered upon completion of the requisite 10 wheel revolutions. Food hoarding (pellets hoarded) was defined as the number of pellets found in the bottom burrow cage in addition to those removed from the cheek pouches. For the 10 wheel revolutions per pellet group, food intake (pellets eaten) was defined as pellets earned minus pellets left in the top cage (surplus pellets) and pellets hoarded. For the nonwheel running contingent food access groups, food intake (pellets eaten) was defined as pellets given (400 pellets) minus pellets left in the top cage and pellets hoarded. An electronic balance used to weigh the food pellets was set to parts measurement; thus one 75-mg food pellet = 1 and fractions of a pellet were computed by the scale.

Experiment 1: Do Subthreshold Doses of NPY and AgRP Interact to Increase Ingestive Behavior?

Performing pilot experiments, we were able to determine subthreshold doses of both NPY (0.0176 nmol) and AgRP (0.01 nmol) that did not induce any of the three behaviors above that of saline controls, with the lowest doses producing behavioral increases being NPY: 0.088 nmol and AgRP: 0.05 nmol; that is, we are using doses five times lower than the lowest effective dose that stimulated these behaviors for each peptide. After those determinations, 42 Siberian hamsters were trained in the foraging/hoarding apparatuses and were then separated into three foraging groups: 10 revolutions/pellet (10REV; access to food contingent upon running 10 wheel revolutions per pellet), free wheel [FW; food was available noncontingently (not earned), but the running wheel was active (locomotor activity control group)], or blocked wheel [BW; food was available noncontingently (not earned), but the running wheel was blocked (sedentary control group)]. The groups were balanced for percent body mass change and average hoard size. On test days, animals were injected at light-offset with one of four 3V injections: 1) saline, 2) 0.0176 nmol NPY, 3) 0.01 nmol AgRP, or 4) 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP dissolved in sterile isotonic saline. Following these injections, food intake, wheel running, and food hoarding are recorded at 1, 2, 4, and 24 h, and 2 and 3 days postinjection. After a 1-wk washout period, a length previously determined to yield a return to baseline, the same protocol was repeated until each animal received all peptide treatments in a repeated-measures, counterbalanced design. After the final test day, the animals were perfused and brains were processed and collected as described above.

Experiment 2: Do Subthreshold Doses of NPY and AgRP Interact to Activate Central Neuronal Activity?

Ninety-eight Siberian hamsters were selected from the breeding colony and housed individually in shoebox cages before and after 3V cannula implantation. Experiment 2 was conducted using a separate group of animals due to the within-subject design of experiment 1 not allowing for an unconfounded test of neural activation (c-Fos-ir). The animals received a 3V injection of one of the following four treatments: 1) saline, 2) 0.0176 nmol NPY, 3) 0.01 nmol AgRP, or 4) 0.0176 nmol NPY+ 0.01 nmol AgRP dissolved in sterile isotonic saline. The animals were injected at light-offset and then were perfused at 90 min or 14 h postinjection and processed for c-Fos-ir (sc-52; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) using our previously described methods for immunohistochemistry (37). The 90-min time point postinjection was chosen based on the predominant increases in food intake seen during that interval with 3V injection of suprathreshold doses of NPY (13, 18, 32) or of AgRP (17), as well as experiment 1. The 14-h time point was chosen because it was the midpoint of the interval ending at 4 h (the latest postinjection interval where food hoarding was not increased) and the interval where food hoarding was first increased (4–24 h) based on the data from experiment 1 (see below). c-Fos-ir was then counted across each entire structure using light microscopy with the counter blind to the treatment regimen. Specific nuclei were selected a priori based upon the available literature where NPY or AgRP injection resulted in c-Fos-ir and any other nuclei that appeared to have increased c-Fos-ir during quantification. To reduce the probability of counting the same neuron twice, Abercrombie's correction factor was used (1).

Statistical Analyses

In experiment 1, raw data for each individual animal were transformed into percent change from saline before statistical analyses according to the formula: {[(x − saline)/saline]*100}, where x is the value measured in response to peptide treatment (0.0176 nmol NPY, 0.01 nmol AgRP, or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP) and saline is the variable response to saline treatment for each behavior and time point. For all measures of food intake, foraging and food hoarding in experiment 1, the data are graphed as the mean percent difference from saline treatment (100%) ± SE. No statistical comparisons are reported across time within a test day or among foraging treatments, as there were no significant differences after the analysis of the full data set using repeated-measures ANOVA. Therefore, analyses only were run within time points using two-way ANOVA. c-Fos-ir data from experiment 2 were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. All statistical analyses were run using NCSS (version 2007; Kaysville, UT). Exact probabilities and test values were omitted for simplicity and clarity of presentation. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Do Subthreshold Doses of NPY and AgRP Interact to Increase Ingestive Behavior?

Wheel running.

Subthreshold doses of NPY or of AgRP given alone did not stimulate wheel running activity that was not coupled to foraging (i.e., FW group, Fig. 1, A and B, respectively), suggesting there was not nonspecific stimulation of locomotor activity by these low doses of neuropeptides when given alone. When the subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP were coinjected into the 3V, FW group wheel revolutions increased significantly during the 0–1 h postinjection interval (∼1,700%, P < 0.05; Fig. 1C), however.

Fig. 1.

Mean ± SE % difference from saline of wheel revolutions in response to 3rd ventricular (3V) injection of 0.0176 nmol neuropeptide Y (NPY; A), 0.01 nmol agouti-related protein (AgRP; B), or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP (C) in Siberian hamsters with no foraging requirement and a freely moving wheel (Free Wheel Revolutions) and 0.0176 nmol NPY (D), 0.01 nmol AgRP (E), or 0.0176 nmol NPY+ 0.01 nmol AgRP (F) in Siberian hamsters with a 10 wheel revolutions per pellet foraging requirement (10 Rev). * P < 0.05 vs. saline controls.

Foraging.

3V injection of subthreshold doses of either NPY (Fig. 1D) or of AgRP (Fig. 1E) did not significantly increase foraging. When the subthreshold doses of each were given together, however, foraging was significantly increased compared with saline control injections during the 0- to 1-h postinjection interval (∼700%, P < 0.05; Fig. 1F).

Food intake.

Subthreshold doses of either NPY (Fig. 2A) or of AgRP (Fig. 2B) did not stimulate food intake in any treatment group during any time interval with the exception of a ∼600% increase during the first hour in the BW group when given only AgRP (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). 3V injection of both NPY and AgRP together significantly increased food intake during the first hour for all foraging groups (∼400–900%) compared with saline (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). The foraging condition alone did not affect food intake.

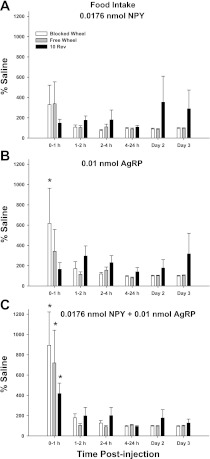

Fig. 2.

Mean ± SE % difference in food intake in response to 3V injection of 0.0176 nmol NPY (A), 0.01 nmol AgRP (B), or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP (C) with no foraging requirement and a stationary wheel (Blocked Wheel, white bars), hamsters with no foraging requirement and a freely moving wheel (Free Wheel, gray bars), and hamsters with a 10 wheel revolutions per pellet foraging requirement (10 Rev, black bars). *P < 0.05 within foraging condition compared with saline controls.

Food hoarding.

3V injection of either NPY (Fig. 3A) or of AgRP (Fig. 3B) did not significantly increase food hoarding in any group at any time. Subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP given together, however, significantly increased food hoarding during the 4–24 h postinjection interval for all foraging groups (∼500–700%) compared with saline (P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). In addition, NPY + AgRP significantly increased food hoarding in the 10REV group during day 2 (∼700%, P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). Foraging condition alone did not affect food hoarding.

Fig. 3.

Mean ± SE % difference in food hoarding in response to 3V injection of 0.0176 nmol NPY (A), 0.01 nmol AgRP (B), or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP (C) with no foraging requirement and a stationary wheel (Blocked Wheel, white bars), hamsters with no foraging requirement and a freely moving wheel (Free Wheel, gray bars), and hamsters with a 10 wheel revolutions per pellet foraging requirement (10 Rev, black bars). *P < 0.05 within foraging condition compared with saline controls.

Experiment 2: Do Subthreshold Doses of NPY and AgRP Interact to Activate Central Neuronal Activity?

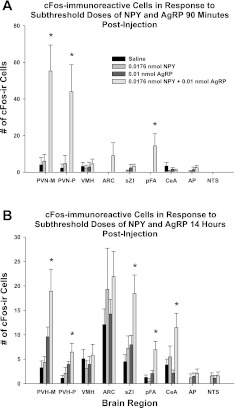

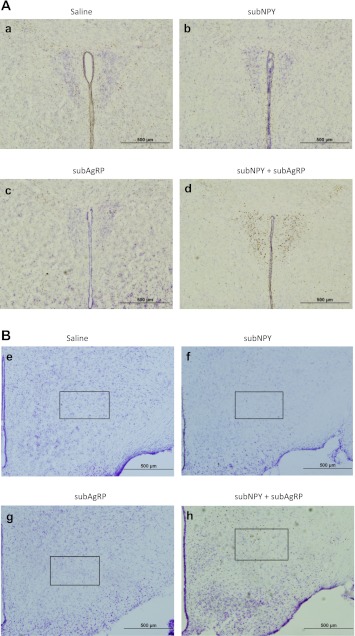

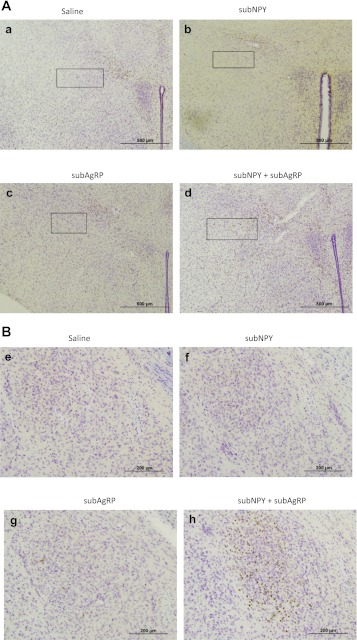

Administration of subthreshold NPY or of subthreshold AgRP alone did not lead to a significant increase in c-Fos-ir at either time period compared with their saline-injected counterparts (Fig. 4). Significant increases in c-Fos-ir occurred at 90 min (Fig. 4A) and 14 h (Fig. 4B) postinjection of NPY+AgRP compared with saline (Figs. 5 and 6, respectively). Specifically, after 90 min, c-Fos-ir was significantly increased in the PVH (magno- and parvicellular regions; Fig. 5, A–D) and the pFA of the lateral hypothalamus (Fig. 5, E–H) compared with the saline-treated group (P < 0.05). Other areas that have increased c-Fos-ir in response to food deprivation (42), AgRP (23, 57), or NPY (44), such as the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH), ARC, central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and area postrema (AP), also were examined and did not have increased c-Fos-ir after any of the treatments compared with saline. At 14 h postinjection, c-Fos-ir was significantly increased in the PVH (magno- and parvicellular regions), sub-zona incerta (sZI; Fig. 6, A–D), pFA, and CeA (Fig. 6, E–H) after coadminstration of subthreshold doses of both NPY and AgRP compared with the saline-injected controls (P < 0.05). The VMH, ARC, AP, and NTS did not have increased c-Fos-ir compared with saline treatment. Note that the quantification of c-Fos-ir was not limited to the regions described above, but other regions did not have significant changes in c-Fos-ir.

Fig. 4.

Mean ± SE c-Fos immunoreactive cells in response to 3V injection of saline, 0.0176 nmol NPY, 0.01 nmol AgRP, or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP 90 min postinjection (A) and 14 h postinjection (B). PVH-M, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus-magnocellular region; PVH-P, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus-parvicellular region; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamus; ARC, arcuate nucleus; sZI, sub-zona incerta; pFA, perifornical area; CeA, central nucleus of the amygdale; AP, area postrema; NTS, nucleus of the tractus solitaries. *P < 0.05 compared with saline controls.

Fig. 5.

Representative photographs of c-Fos-ir in response to 3V injection of saline, 0.0176 nmol NPY, 0.01 nmol AgRP, or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus after 90 min (A, a–d; ×10 magnification), the pFA after 90 min (B, e–h; ×10 magnification with box delineating the region).

Fig. 6.

Representative photographs of c-Fos-ir in response to 3V injection of saline, 0.0176 nmol NPY, 0.01 nmol AgRP, or 0.0176 nmol NPY + 0.01 nmol AgRP in the sZI after 14 h (A, a–d; ×10 magnification with box delineating the region), and the central nucleus of the amygdala after 14 h (B, e–h; ×10 magnification).

DISCUSSION

NPY and AgRP are important orexigenic factors underlying ingestive behavior in a variety of conditions and species (for review see Ref. 6). Here we found that 3V coinjection of subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP resulted in significant increases in ingestive behaviors as well as in neural activation in brain nuclei shown to be involved in the response to food deprivation and/or NPY or AgRP injection previously in other species (for review see Ref. 6). NPY and AgRP are nearly exclusively colocalized in neurons originating in the ARC, including in Siberian hamsters (40), thereby creating the possibility of co-release of a cocktail containing each neuropeptide (20, 25, 40). The timing of the peak in food hoarding was different from food intake, with food intake peaking during the first hour postinjection of NPY+AgRP and food hoarding being elevated at 4–24 h and 2 days after injection. The distribution of significant c-Fos-ir after coinjection of subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP also was different between the two time points, and at neither time point was c-Fos-ir increased above saline in any structure examined with subthreshold NPY or AgRP injection. The PVH (magno- and parvicellular regions) and pFA had increased c-Fos-ir at both time points with the CeA, and sZI c-Fos-ir only increased 14 h postinjection. The VMH, ARC, AP, and NTS did not have an increase in c-Fos-ir at either time point. Thus, these data show, for the first time that: 1) coinjection of subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP can lead to increases in food hoarding and intake; 2) that there is a temporal separation in food intake (0–1 h) and food hoarding (4–24 h and 2 days); and 3) there are corresponding significant increases in neural activation, as indicated by c-Fos-ir that also largely are time dependent.

In our previous tests of the effects of NPY or AgRP on food hoarding, we focused on doses that were sufficient to elicit increases in hoarding at levels similar to those induced by food deprivation (36–56 h). The temporal pattern of increased hoarding depended upon which of these peptides was administered. Thus, acute NPY injection (3V, or parenchymal injections into the PVH, pFA) causes a short-lived, early rise in food foraging, hoarding, and intake levels [largely within the first few hours, up to 2 days; (18)], whereas AgRP (3V) also causes significant increases as early as 1 h postinjection, but causes a marked increase in food hoarding that persists for several days postinjection [3–6 days (17)]. To have a better understanding of the possible interaction of NPY and AgRP on these appetitive ingestive behaviors, we administered each peptide at subthreshold doses in tandem, as they are colocalized and, possibly, co-released to increase food intake (25). Our data show that subthreshold doses of NPY or AgRP alone do not result in consistent increases in food hoarding or intake, but in combination are able to trigger increases in food intake and (0–1 h) and food hoarding (4 h–2 days). The one exception to the lack of AgRP or NPY effect when administered alone was subthreshold AgRP increased food intake at 0–1 h postinjection only in BW animals, this was unexpected based on pilot data to determine a subthreshold dose of AgRP. The combination of subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP did result in increased wheel running in FW animals; typically this would suggest that our treatment caused nonforaging-specific increases in activity and that increased activity, at least in part, could lead to the increased food intake and hoarding. Using our BW group, we can rule this increased activity out as the cause of increased food intake at the 0–1 h time point, because the BW group also had increased food intake in response to the coinjection of subthreshold NPY and AgRP. The increase in noncontingent wheel running (FW) and food foraging (10REV) in the first hour post-NPY and AgRP injection suggests that the increased activity was perhaps not food directed per se.

To our knowledge, only two other studies have examined the interaction of subthreshold doses of orexigenic factors on increasing food intake in rodents (46, 54). In the first, a subthreshold dose of AgRP was combined with a suprathreshold dose of NPY injected together in the PVH, resulting in increased food intake above AgRP alone, suggesting an interaction (54). NPY and AgRP have been coinjected in sheep at suprathreshold doses; however, there was no interaction such that food intake is not different than when the same dose of each is applied alone (51), possibly due to a ceiling effect on food intake or perhaps to species differences. In the second study of subthreshold doses of orexigenic factors interacting to affect food intake, subthreshold doses of NPY increased food intake when combined with either subthreshold orexin A or subthreshold melanin concentrating hormone (46). By stark contrast, there are several well-known examples of subthreshold doses of anorexigenic factors in combination that inhibit food intake [i.e., estradiol and cholecystokinin (22) and leptin and cholecystokinin (2)]. The data here are the first, however, to use subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP in combination to test their interaction with regard to food foraging and hoarding. Furthermore, these results appear to be a reasonable starting point in the quest to understand mechanisms involved in the daily control of the appetitive ingestive behavior of food hoarding.

In our second experiment, we expanded our behavioral data and tested for neural activation, as assayed by c-Fos-ir, in response to single acute 3V injection of subthreshold doses of either NPY or AgRP as well as their combination. We recognize the caveats of c-Fos-ir as an indicator of neural activation (28) in that the absence of proof is not the proof of absence given that some neurons use other immediate-early genes and that neuronal inhibition does not trigger neuronal expression of c-Fos. Therefore, we interpret the present findings knowing they are suggestive, at best, but nevertheless a commonly used, accepted, and starting point for determining brain sites affected by a given manipulation.

Food deprivation and ghrelin both increase c-Fos-ir in laboratory rats and mice, as might be expected given their role in triggering various ingestive behaviors. Food deprivation causes increases in c-Fos-ir indicating neural activation [e.g., (41, 42, 48)], with the nuclei showing increases in c-Fos-ir varying depending upon the species, strain, and phenotype of the animal examined. Despite the variation, a pattern of c-Fos-ir emerges with the ARC and PVH (magno- and parvicellular regions), typically showing labeling and occasionally the CeA. Exogenous ghrelin administration triggers c-Fos-ir in the ARC NPY/AgRP expressing neurons [e.g., (9, 49, 52)] as well as promoting increases in NPY and AgRP mRNA expression [e.g., (29, 34)]. Therefore, it is not surprising that central NPY or AgRP administration increases c-Fos-ir [e.g., (23, 57)]. In the present experiment, at our first time point, 90 min postinjection, the increased c-Fos-ir occurred in a distribution pattern similar to that of central NPY [e.g., (36, 56)] or AgRP [e.g., (23, 57)] given alone by others in different species assayed within 2 h after injection of either peptide. In brief, in the present finding, only when acute coinjection of subthreshold doses of both AgRP and NPY did c-Fos-ir increase 90-min postinjection in the PVH and pFA, but not additional areas (sZI, VMH, ARC, CeA, NTS, and AP) shown by others in other species to be responsive to NPY and/or AgRP at concentrations above threshold (23, 36, 56, 57) or in the present study (sZI and CeA) at the later time point postinjection (14 h).

The typical time course used for assaying c-Fos-ir as a marker of neural activation is within the first 2 h of treatment, with longer intervals seldom used, likely because of the classic immediate-early characteristic of this marker [23–24 h; (23, 57)] as well as the likelihood of secondary sites of action showing neuronal activation. Using later time points, however, can permit assessment of behaviors or treatments that differ in their temporal signature, for example, the lingering increases in the orexigenic effects of suprathrehold acute central injection of AgRP (23, 57). In laboratory rats, a single AgRP injection causes neural activation that is still apparent after 23–24 h in several brain areas (pFA, ARC, PVH, CeA, and NTS) and differs, in part, from the c-Fos-ir at 2 h postinjection (PVH, DMN). Here we used a second time point that was 14 h after treatment to find brain regions that could be uniquely activated at a time when food hoarding is maximally elevated, but not food intake. At the later time point (14 h), there was a different c-Fos-ir profile than that after 90 min. Specifically, c-Fos-ir increased in the PVH (magno- and parvicellular regions), sZI, pFA, and CeA, and not in the ARC, VMH, NTS, or AP. Individual injection of subthreshold doses of NPY or of AgRP did not increase c-Fos-ir compared with saline, a result expected given the behavioral data. Therefore, these data provide evidence that NPY and AgRP interact to stimulate areas of the brain known to be activated by neurochemical controllers of energy intake/expenditure (i.e., NPY, AgRP, ghrelin). In addition, the data offer possible discrete locations for the control of different portions of the ingestive behavior sequence. Specifically, the sZI and CeA exhibit an interesting pattern of c-Fos-ir, with increased immunoreactivity coinciding with the increase in food hoarding. For example, taken at face value, it could be argued that the combination of NPY and AgRP together act to increase food intake/foraging and hoarding through unique structures and/or messaging systems. The present data supports previous data that AgRP can act via the CeA to cause the extended increases in ingestive behavior (23, 57) and leads to a hypothesis positing that administration of a subthreshold dose of NPY potentiates the effect of a subthreshold dose of AgRP, or vice versa, on food hoarding perhaps involving the CeA. A more direct examination of these sites is warranted to further elucidate the mechanism by which food intake and hoarding are disassociated in response to food deprivation and the accompanying physiological signals.

It is possible that the different patterns of c-Fos-ir seen between the two points is due to the different time of day that the tissue was collected, but saline-induced c-Fos-ir is not different between the two time points. Another possible explanation for the increased c-Fos-ir is the increased food intake in the NPY+AgRP-treated animals. This is a difficult potential confound to eliminate experimentally, where to our knowledge the choices are to clamp food intake of NPY+AgRP animals to that of controls (pair feeding) as done by Zheng et al. (57) in their animals injected with AgRP 3V and sampled 23 h later or have the animals food deprived for the entire period. Both add the effects of caloric restriction/deprivation into the mix of the peptide injections, however. Thus, the perfect control escapes us.

In previous ingestive behavioral studies, we aimed, in part, to determine the individual roles of NPY and AgRP, and much of the work is detailed above (17, 18). Our present findings, as well as those of others (23, 24), have led to a possible alternative explanation of our initial work, especially regarding melanotan II (MTII), a MC 3/4R agonist, administration after a food deprivation (31). In brief, 3V administration of MTII only partially attenuates the increases in food hoarding after a 48-h food deprivation, but MTII was able to inhibit ghrelin-induced increases in food hoarding (30). The differences in efficacy of MTII to inhibit food hoarding was initially interpreted as being due to other food deprivation-specific factors even though food deprivation does cause increased ghrelin release. This interpretation is certainly possible (8, 25), but it overlooks the gradual increase in serum concentrations of ghrelin that occurs over the duration of the food deprivation, and this increase may have already initiated the AgRP/MC 3/4R component of food hoarding (30). MTII administered 24 h after AgRP is able to inhibit the AgRP-induced increases in food intake, but this suppression wanes after < 48 h, and food intake returns to the level of the animals treated with AgRP and vehicle 24 h later (24). Our present data (coinjection of subthreshold doses NPY and AgRP), together with that of others [AgRP (23, 57), AgRP + MTII 24 h later (24)] suggest a prolonged, possibly secondary effect that is due to downstream changes not prolonged AgRP/MC 3/4R interaction.

With regard to a possible mechanism underlying the interaction between AgRP and NPY that results in increased food hoarding and intake, we only offer speculation. As noted above (introduction), individual neurons within the PVH receive ARC efferents containing both NPY and AgRP as demonstrated immunohistochemically (11). Moreover, using a hypothalamic slice preparation, single PVH neurons respond electrophysiologically to both NPY and AgRP (11), suggesting shared PVH target neurons perhaps from ARC NPY/AgRP projections (11). Thus, based on these data, Cowley et al. (11) suggested that the co-release of these two orexigenic peptides may have harmonizing effects on food intake by inhibiting GABAergic input concurrently with blocking the exaggeration of this input by α-MSH. This possibility could be in play in the PVH as well as in other ARC projection areas (e.g., pFA/lateral hypothalamus) and perhaps underlie the increases in hoarding and food intake with the 3V NPY+AgRP subthreshold injections seen here. It would be incorrect, however, to believe that NPY duplicates AgRP effects and vice versa in these areas for these behaviors, as parenchymal injection studies of each single peptide as well as overexpression of each singly, results in clearly different effects of AgRP versus NPY on several energy-related responses including food intake, locomotor activity, and body temperature; nevertheless, the effects of each appear complementary in overall energy balance (for review see Ref. 19). Indeed, from the results here and from our previous studies of single injections of NPY or AgRP (13, 17, 18, 32), NPY tends to increase food intake early postinjection, whereas AgRP tends to promote later, sustained increases in food hoarding. Clearly, however, given that the increases in these appetitive and consummatory ingestive behaviors occurred only when subthreshold doses of each are given together in the present experiment, this dichotomous separation is not absolute, with the two peptides interacting to advance both behaviors.

Based on the results from our studies of food deprivation-induced increases in foraging/hoarding in Siberian hamsters, and from studies of food deprivation-induced increases in food intake by laboratory rats and mice, the following possible scenario has emerged. Food deprivation increases the primarily stomach-released peptide ghrelin (35), which in turn stimulates its receptors (growth hormone secretagogue-receptor), some of which are located on neurons in the ARC that colocalize NPY and AgRP (25), a colocalization that also occurs in Siberian hamsters (40). Stimulation of growth hormone secretagogue-receptors on these NPY/AgRP ARC neurons activates these neurons, as evidenced by increases NPY and AgRP gene expression as well as c-Fos-ir. Potentially, then, both peptides could be released in the projection targets of the ARC NPY/AgRP neurons. Collectively, these data point to a possible co-release and interaction of NPY and AgRP under conditions, such as food deprivation.

In the present experiments, we demonstrated, for the first time, that the coadministration of subthreshold doses of NPY and AgRP are able to interact to increase food intake and hoarding and neural activation in the PVH, pFA, sZI, and CeA; other brain regions were examined for increases in c-Fos-ir, but nothing of note was observed. The increase in food intake was within the first hour, and food hoarding was not increased until 4–24 h and 2 days postinjection. The c-Fos-ir pattern was unique to the time at which the tissue was collected and combined with recent hoarding-related c-Fos-ir data in Mongolian gerbils in brain reward circuitry (55); it may be possible to further dissect the mechanism(s) underpinning the temporal disassociation of food intake and food hoarding.

Perspectives and Significance

The prevalence of overweight/obese individuals continues to rise and with it the incidence of many secondary health consequences, such as, but not limited to, type 2 diabetes, stroke, heart disease, and some types of cancer (e.g., for review see Ref. 26). The control of energy balance is of paramount importance in the onset/maintenance/reversal of obesity, and this has been a focus of much research. Despite the considerable gains in understanding the underlying mechanisms controlling the consummatory phase of ingestive behavior, relatively little is known about the appetitive phase. We have recently reviewed the relevance of food hoarding to normal human ingestive behavior as well as in pathological conditions (e.g., Prader-Willi Syndrome), including overweight/obesity (for review, see Refs. 6 and 7). The present data address both phases of ingestive behavior using an animal model not unlike humans in their ability and proclivity to hoard food and the disassociation between appetitive and consummatory ingestive behavior responses (for review, see Refs. 6 and 7), allowing for a deeper understanding of the behavioral sequence leading to energy imbalance. Using doses of NPY and AgRP in tandem that, on their own, are subthreshold to cause food deprivation-like induced increases in ingestive behavior, we were able to show temporal separation of food intake and food hoarding with distinctive patterns of neural activation (i.e., c-Fos-ir). These data, showing the interaction of two neuroactive substances that increase these appetitive behaviors, is another example of the interaction of neuroactive substances that affect ingestive behaviors, such as the interaction of cholecystokinin and leptin (2), cholecystokinin and estradiol (22), or amylin and leptin (43), although those interactions are examples of substances that decrease consummatory ingestive behavior (eating). Only one previous study showed increases based on combination of subthreshold doses of two orexigenic factors (46). Collectively, these interactions demonstrate the complex interplay between neuroactive factors that have been shown to be at least sufficient, and in some cases necessary, for the control of ingestive behaviors. Such cross-talk has the potential for therapeutic treatments of appetitive and/or consummatory ingestive behaviors.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01-DK-078358 (to T. J. Bartness) and F32-DK-091984 (to B. J. W. Teubner).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: B.J.T., E.K.-R., and T.J.B. conception and design of research; B.J.T. and E.K.-R. performed experiments; B.J.T. and E.K.-R. analyzed data; B.J.T., E.K.-R., and T.J.B. interpreted results of experiments; B.J.T. and T.J.B. prepared figures; B.J.T. drafted manuscript; B.J.T., E.K.-R., and T.J.B. edited and revised manuscript; B.J.T., E.K.-R., and T.J.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Department of Animal Resources at Georgia State University for expert animal care, Bianca Lester for assistance in c-Fos-ir quantification, and Dr. Cheryl H. Vaughan for technical assistance.

Present address of Erin Keen-Rhinehart: Department of Biology, Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA 17870.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abercrombie M. Estimation of nuclear populations from microtome sections. Anat Rec 94: 239–247, 1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barrachina MD, Martinez V, Wang L, Wei JY, Tache Y. Synergistic interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin to reduce short-term food intake in lean mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 10455–10460, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartness TJ, Clein MR. Effects of food deprivation and restriction, and metabolic blockers on food hoarding in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R1111–R1117, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartness TJ, Day DE. Food hoarding: a quintessential anticipatory appetitive behavior. Prog Psychobiol Physiol Psychol 18: 69–100, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartness TJ, Demas GE. Comparative studies of food intake: lessons from non-traditionally studied species. In: Food and Fluid Intake, edited by Stricker EM, Woods SC. New York: Plenum, 2004, p. 423–467 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartness TJ, Keen-Rhinehart E, Dailey MJ, Teubner BJ. Neural and hormonal control of food hoarding. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R641–R655, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bartness TJ, Song CK. Brain-adipose tissue neural crosstalk. Physiol Behav 91: 343–351, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradley SP, Pattullo LM, Patel PN, Prendergast BJ. Photoperiodic regulation of the orexigenic effects of ghrelin in Siberian hamsters. Horm Behav 58: 647–652, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corander MP, Rimmington D, Challis BG, O'Rahilly S, Coll AP. Loss of agouti-related peptide does not significantly impact the phenotype of murine POMC deficiency. Endocrinology 152: 1819–1828, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cowley MA, Pronchuk N, Fan W, Dinulescu DM, Colmers WF, Cone RD. Integration of NPY, AGRP, and melanocortin signals in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: evidence of a cellular basis for the adipostat. Neuron 24: 155–163, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Craig W. Appetites and aversions as constituents of instincts. Biol Bull 34: 91–107, 1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dailey MJ, Bartness TJ. Appetitive and consummatory ingestive behaviors stimulated by PVH and perifornical area NPY injections. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R877–R892, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dailey MJ, Bartness TJ. Arcuate nucleus destruction does not block food deprivation-induced increases in food foraging and hoarding. Brain Res 1323: 94–108, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Day DE, Bartness TJ. Effects of foraging effort on body fat and food hoarding by Siberian hamsters. J Exp Zool 289: 162–171, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Day DE, Bartness TJ. Fasting-induced increases in hoarding are dependent on the foraging effort level. Physiol Behav 78: 655–668, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Day DE, Bartness TJ. Agouti-related protein increases food hoarding, but not food intake by Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R38–R45, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Day DE, Keen-Rhinehart E, Bartness TJ. Role of NPY and its receptor subtypes in foraging, food hoarding, and food intake by Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R29–R36, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Backer MW, la Fleur SE, Brans MA, van Rozen AJ, Luijendijk MC, Merkestein M, Garner KM, van der Zwaal EM, Adan RA. Melanocortin receptor-mediated effects on obesity are distributed over specific hypothalamic regions. Int J Obes (Lond) 35: 629–641, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dhillo WS, Small CJ, Stanley SA, Jethwa PH, Seal LJ, Murphy KG, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Hypothalamic interactions between neuropeptide Y, agouti-related protein, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in vitro in male rats. J Neuroendocrinol 14: 725–730, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dodd DK, Stalling RB, Bedell J. Grocery purchases as a function of obesity and assumed food deprivation. Int J Obes 1: 43–47, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geary N, Trace D, McEwen B, Smith GP. Cyclic estradiol replacement increases the satiety effect of CCK-8 in ovariectomized rats. Physiol Behav 56: 281–289, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hagan MM, Benoit SC, Rushing PA, Pritchard LM, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Immediate and prolonged patterns of agouti-related peptide-(83–132)-induced c-Fos activation in hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic sites. Endocrinology 142: 1050–1056, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hagan MM, Rushing PA, Pritchard LM, Schwartz MW, Strack AM, Van Der Ploeg LH, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Long-term orexigenic effects of AgRP-(83–132) involve mechanisms other than melanocortin receptor blockade. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R47–R52, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hahn TM, Breininger JF, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nat Neurosci 1: 271–272, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. JAMA 291: 2847–2850, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hetherington MM, Stoner SA, Andersen AE, Rolls BJ. Effects of acute food deprivation on eating behavior in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 28: 272–283, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffman GE, Smith MS, Verbalis JG. c-Fos and related immediate early gene products as markers of activity in neuroendocrine systems. Front Neuroendocrinol 14: 173–213, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamegai J, Tamura H, Shimizu T, Ishii S, Sugihara H, Wakabayashi I. Chronic central infusion of ghrelin increases hypothalamic neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein mRNA levels and body weight in rats. Diabetes 50: 2438–2443, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keen-Rhinehart E, Bartness TJ. Peripheral ghrelin injections stimulate food intake, foraging and food hoarding in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R716–R722, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keen-Rhinehart E, Bartness TJ. MTII attenuates ghrelin- and food deprivation-induced increases in food hoarding and food intake. Horm Behav 52: 612–620, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keen-Rhinehart E, Bartness TJ. NPY Y1 receptor is involved in ghrelin- and fasting-induced increases in foraging, food hoarding, and food intake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1728–R1737, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keen-Rhinehart E, Dailey MJ, Bartness TJ. Physiological mechanisms for food-hoarding motivation in animals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365: 961–975, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kinzig KP, Scott KA, Hyun J, Bi S, Moran TH. Lateral ventricular ghrelin and fourth ventricular ghrelin induce similar increases in food intake and patterns of hypothalamic gene expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1565–R1569, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 402: 656–660, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lambert PD, Phillips PJ, Wilding JP, Bloom SR, Herbert J. c-fos expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus following intracerebroventricular infusions of neuropeptide Y. Brain Res 670: 59–65, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leitner C, Bartness TJ. Food deprivation-induced changes in body fat mobilization after neonatal monosodium glutamate treatment. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R775–R783, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Levitsky DA, DeRosimo L. One day of food restriction does not result in an increase in subsequent daily food intake in humans. Physiol Behav 99: 495–499, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mela DJ, Aaron JI, Gatenby SJ. Relationships of consumer characteristics and food deprivation to food purchasing behavior. Physiol Behav 60: 1331–1335, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mercer JG, Moar KM, Ross AW, Hoggard N, Morgan PJ. Photoperiod regulates arcuate nucleus POMC, AGRP, and leptin receptor mRNA in Siberian hamster hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R271–R281, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mistry AM, Helferich W, Romsos DR. Elevated neuronal c-Fos-like immunoreactivity and messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) in genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. Brain Res 666: 53–60, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Olson BR, Freilino M, Hoffman GE, Stricker EM, Sved AF, Verbalis JG. c-Fos expression in rat brain and brainstem nuclei in response to treatments that alter food intake and gastric motility. Mol Cell Neurosci 4: 93–106, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Osto M, Wielinga PY, Alder B, Walser N, Lutz TA. Modulation of the satiating effect of amylin by central ghrelin, leptin and insulin. Physiol Behav 91: 566–572, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pomonis JD, Levine AS, Billington CJ. Interaction of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and central nucleus of the amygdala in naloxone blockade of neuropeptide γ-induced feeding revealed by c-fos expression. J Neurosci 17: 5175–5182, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reddy AB, Cronin AS, Ford H, Ebling FJ. Seasonal regulation of food intake and body weight in the male Siberian hamster: studies of hypothalamic orexin (hypocretin), neuropeptide Y (NPY) and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). Eur J Neurosci 11: 3255–3264, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sahu A. Interactions of neuropeptide Y, hypocretin-I (orexin A) and melanin-concentrating hormone on feeding in rats. Brain Res 944: 232–238, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schwartz MW, Sipols AJ, Grubin CE, Baskin DG. Differential effect of fasting on hypothalamic expression of gene encoding neuropeptide Y, galanin, and glutamic acid decarboxylase. Brain Res Bull 31: 361–367, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Timofeeva E, Richard D. Activation of the central nervous system in obese Zucker rats during food deprivation. J Comp Neurol 441: 71–89, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Toshinai K, Date Y, Murakami N, Shimada M, Mondal MS, Shimbara T, Guan JL, Wang QP, Funahashi H, Sakurai T, Shioda S, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Ghrelin-induced food intake is mediated via the orexin pathway. Endocrinology 144: 1506–1512, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vander Wall SB. Food Hoarding in Animals. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wagner CG, McMahon CD, Marks DL, Daniel JA, Steele B, Sartin JL. A role for agouti-related protein in appetite regulation in a species with continuous nutrient delivery. Neuroendocrinology 80: 210–218, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang L, Saint-Pierre DH, Tache Y. Peripheral ghrelin selectively increases Fos expression in neuropeptide Y-synthesizing neurons in mouse hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Neurosci Lett 325: 47–51, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiner J. Limits to energy budget and tactics in energy investments during reproduction in the Djungarian hamster (Phodopus sungorus sungorus Pallas 1770). Symp Zool Soc Lond 57: 167–187, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wirth MM, Giraudo SQ. Agouti-related protein in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: effect on feeding. Peptides 21: 1369–1375, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang HD, Wang Q, Wang Z, Wang DH. Food hoarding and associated neuronal activation in brain reward circuitry in Mongolian gerbils. Physiol Behav 104: 429–436, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yokosuka M, Kalra PS, Kalra SP. Inhibition of neuropeptide Y (NPY)-induced feeding and c-Fos response in magnocellular paraventricular nucleus by a NPY receptor antagonist: a site of NPY action. Endocrinology 140: 4494–4500, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zheng H, Corkern MM, Crousillac SM, Patterson LM, Phifer CB, Berthoud HR. Neurochemical phenotype of hypothalamic neurons showing Fos expression 23 h after intracranial AgRP. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1773–R1781, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]