Abstract

Previous studies demonstrated that overexpression of angiotensinogen (AGT) in adipose tissue increased blood pressure. However, the contribution of endogenous AGT in adipocytes to the systemic renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and blood pressure control is undefined. To define a role of adipocyte-derived AGT, mice with loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the AGT gene (Agtfl/fl) were bred to transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of an adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein 4 promoter (aP2) promoter to generate mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency (AgtaP2). AGT mRNA abundance in adipose tissue and AGT secretion from adipocytes were reduced markedly in adipose tissues of AgtaP2 mice. To determine the contribution of adipocyte-derived AGT to the systemic RAS and blood pressure control, mice were fed normal laboratory diet for 2 or 12 mo. In males and females of each genotype, body weight and fat mass increased with age. However, there was no effect of adipocyte AGT deficiency on body weight, fat mass, or adipocyte size. At 2 and 12 mo of age, mice with deficiency of AGT in adipocytes had reduced plasma concentrations of AGT (by 24–28%) compared with controls. Moreover, mice lacking AGT in adipocytes exhibited reduced systolic blood pressures compared with controls (Agtfl/fl, 117 ± 2; AgtaP2, 110 ± 2 mmHg; P < 0.05). These results demonstrate that adipocyte-derived AGT contributes to the systemic RAS and blood pressure control.

Keywords: adipose tissue, age

the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a major role in control of blood pressure. Angiotensinogen (AGT) is the only known precursor for production of angiotensin II (ANG II). ANG II increases blood pressure by increasing peripheral vascular resistance, increasing sympathetic nervous system activity, and through the control of sodium homeostasis. While the systemic RAS is recognized as an important endocrine system for blood pressure control, local production of ANG II by various cell types and/or tissues has also been implicated in the pathophysiology of hypertension.

In 1994, Tanimoto et al. (35) demonstrated that mice with whole body deficiency of AGT had marked decreases of systemic concentrations of AGT and blood pressure (by 34 mmHg). These results demonstrated a primary role for AGT in the systemic RAS and blood pressure control. It is generally accepted that liver hepatocytes serve as a primary source for systemic AGT concentrations as the substrate for systemic concentrations of ANG II. Previous studies demonstrated that adipose tissue is a major extra-hepatic source of AGT (2, 3, 5, 8). ANG is also expressed in several other extra-hepatic peripheral tissues, including kidney, adrenal, and brain (3, 8). Further studies demonstrated that adipose tissue possesses each component necessary for the production of ANG II from AGT, including renin-like activity (13, 21, 27, 30, 32) and angiotensin converting enzyme.

Given that adipocytes express high levels of AGT mRNA, it is conceivable that adipocyte-derived AGT contributes to plasma AGT concentrations and blood pressure control. In mice with targeted overexpression of AGT in adipose tissue, increases were observed in plasma AGT concentrations (22 to 44%) and blood pressure (16). Moreover, transgenic expression of AGT in adipose tissue of mice with whole body AGT deficiency modestly increased plasma AGT concentrations and partially restored blood pressure. These results were the first to suggest that adipocyte-derived AGT could modulate the systemic RAS; however, the contribution of endogenous AGT production by adipocytes to the systemic RAS and blood pressure control has not been defined.

In this study, to define the role of adipocyte-derived AGT to the systemic RAS and blood pressure control, mice with loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the AGT gene were bred to mice expressing an adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein 4 promoter (aP2)-driven transgenic Cre recombinase to create mice with specific deletion of AGT in adipocytes. To define the role of adipocyte-derived AGT to the systemic RAS and blood pressure control, we examined age-dependent effects of adipocyte AGT deficiency in male and female mice. Two months of age was chosen to represent early adulthood, while 12 mo was chosen as an age representing ∼50% of the lifespan for the C57BL/6 strain (22). Results demonstrate that adipocyte-derived AGT contributes to systemic AGT concentrations and blood pressure control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of adipocyte-specific AGT knockout mice.

Mice with loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the AGT gene (1,672 bp, including exon 2) were created by transfecting a targeting vector that was subcloned from a positively identified BAC clone (C57BL/6) and electroporated into hybrid ES cells. For positive selection of homologous recombinants, an Frt-flanked neomycin resistance gene (neo) was cloned 3′ upstream of exon 3 (termed Agtfl/fl, Fig. 1; InGenious Targeting, Stony Brook, NY). The neomycin cassette was removed by breeding to FLPe mice [B6.SJL-Tg(ACTFLPe)9205Dym/J, cat. no. 03800; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME]. Mice with deficiency of AGT in adipocytes were derived by breeding aP2-Cre0/0, Agtfl/fl females to transgenic male mice expressing Cre recombinase (aP2-Cre1/0, AgtaP2) under the control of an aP2 promoter/enhancer Cg-Tg (Fabp4-cre1Rev/J; cat. no. 005069, Jackson Laboratory). For all studies, male and female Agtfl/fl littermate controls were used for comparison to mice with adipocyte-AGT deficiency (AgtaP2).

Fig. 1.

Development of mice with adipocyte deficiency of angiotensinogen (AGT). A: schematic representation of the loxP-flanked AGT allele before (a) and after successive recombination with Flp (b) and transgenic fatty acid-binding protein 4 promoter (aP2)-driven Cre expression (c). The disrupted allele is shown in (c), indicating deletion of exon 2 of the AGT gene. B: genotyping of different adipose tissues [retroperitoneal fat (RPF), epididymal fat (EF), subcutaneous fat (Subc), and brown adipose tissue (BAT)] from Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice. Amplicons are 249 bp (Agtfl/fl wild-type) or 362 bp (AgtaP2, disrupted). Since DNA from whole adipose tissue extracts were probed using PCR primers, the presence of an amplicon at 249 bp in AgtaP2, most likely results from the presence of other cell types in adipose tissue. C: AGT mRNA abundance in adipose and nonadipose tissues from Agtfl/fl control and AgtaP2 mice. Data are means ± SE from n = 4–11/group; *P < 0.05 compared with Agtfl/fl.

Animals and experimental protocol.

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky. Mice of each genotype were fed normal laboratory diet (18% protein, Global Diet; Teklad Harlan Madison, WI) for 2 or 12 mo (range 12–14 mo). Mice were provided water and diet ad libitum. Fat mass (expressed as % lean mass) was measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (LUNAR PIXImus, Janesville, WI) at the study's end point. Blood was collected from anesthetized mice (ketamine/xylazine, 100·10 mg−1·kg−1 ip), just prior to study termination, in tubes (4°C) containing EDTA (0.2 M), centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. Plasmas were stored at −80°C. Tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Measurement of fasting blood glucose and glucose tolerance.

Mice were fasted for 6 h before quantification of blood glucose concentrations. For glucose tolerance tests, blood glucose was quantified at 0 min before injection of glucose solution (2 mg/kg body wt) and at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after injection as described previously (19).

Measurement of leptin and insulin in plasma.

Plasma concentrations of leptin and insulin were quantified in fed mice using a mouse leptin (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and mouse insulin Elisa kit (Millipore).

Measurement of systolic blood pressure.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was measured on conscious, restrained mice via the Visitech BP-2000 tail cuff system (6). Briefly, SBP was quantified for 5–10 days, and measurements were taken at the approximate same time each day. Each cycle consisted of 10 preliminary tail cuff inflation/deflations for daily acclimation followed by 10 additional cycles that were recorded. Criteria for inclusion of measurements from individual mice were at least four out of ten successful measurements with a SD of < 50 required for inclusion.

DNA genotyping.

DNA was isolated from four different adipose tissues: retroperitoneal fat (RPF), epididymal fat (EF), subcutaneous fat (Subc), and brown adipose tissue (BAT). The following primers were used in adipose tissues for the identification of the targeted allele Agtfl/fl (wild type, after FLPe-mediated recombination) and for the identification of the deletion of exon 2 (disrupted, after FLPe-mediated recombination and Ap2-Cre-mediated recombination): 5′-AACCTTGTCTGGAGTGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAGAGATCCGTGGGAAC-3′ (reverse 1) and TCCACCTCACAGGTAGCAATG (reverse 2). PCR was performed using the GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega). PCR conditions were one cycle at 95°C for 4 min followed by 35 cycles (step 1: 95°C for 1 min; step 2: 57°C for 1 min; step 3: 72°C for 1 min) and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min (Thermal iCycler; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). DNA gels were visualized with the Image Station 4000MM (Kodak, Eastman, NY) by using Molecular Imaging Software (the autocontrast function was used).

Tissue RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR.

Tissue RNA was isolated using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI). RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically (260 nm) using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo-Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and reverse transcribed (0.1 μg of RNA from liver, kidney, brain, EF, and RPF or 1 μg of RNA from heart, lung, spleen, BAT, or Subc group) using a Retroscript kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). cDNAs were amplified using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA). Estimation of amplified gene products was normalized to 18S RNA. Primer sequences used are as follows: AGT: forward: 5′-GTACAGACAGCACCCTACTT-3′, reverse: 5′-CACGTCACGGAGAAGTTGTT-3′. 18s forward: 5′-AGTCGGCATCGTTTATGGTC-3′, reverse: 5′-CGAAAGCATTTGCCAAGAAT-3′; aP2: forward: 5′-TCACCTGGAAGACAGCTCCT-3′, reverse: 5′-AAGCCCACTCCCACTTCTTT-3′.

Measurement of AGT in plasma and media.

To quantify AGT production by adipocytes, the stromal vascular fraction was harvested from collagenase digestion (1 mg/ml) of subcutaneous adipose tissue according to the method of Rodbell (23). Cells were grown to confluence in preadipocyte medium (OM-PM; Zenbio). Two days after confluence (day 0), cells were incubated with adipocyte differentiation medium (OM-DM) with media replaced every other day. Media (125 μl) were harvested at 0 and 8 days of differentiation for quantification of AGT concentrations using mouse total angiotensinogen assay kits (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan). For plasma, 10 μl was used for measurement of AGT.

Histological analyses of adipocytes.

Gonadal adipose tissue (EF in males, periovarian adipose in females) was fixed with formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections of adipose tissue from each mouse (n = 3 mice/group) were photographed under ×100 magnification. In a square measuring 700 × 700 μm (x- and y-axis, respectively), adipocyte size and number were measured using NIS Elements BR.3.10 software. A criterion for inclusion of measurements was a circularity of adipocytes superior to 0.33 [shape of cells; from 0 (thin shape) to 1 (perfect circle)].

Statistical analyses.

Data are summarized as means ± SE. We used Student's t-tests to compare two groups defined by one factor (genotype), two-way ANOVA to compare four groups defined by two factors (genotype and age), and three-way ANOVA to compare eight groups defined by three factors (genotype, age, and gender). Where necessary, due to markedly unequal within-group variances, we modified ANOVA by weighting observations according to the reciprocals of the within-group variances. We used repeated-measures ANOVA to compare two groups assessed repeatedly over time. Where necessary, due to marked nonnormality, we modified repeated-measures ANOVA by first applying a square root transformation to the observations. We used linear regression to assess associations of SBP with percent fat mass, while adjusting for and/or stratifying by one or more factors, such as genotype, age, and gender. The standardized regression coefficient estimates thereby obtained may be interpreted essentially like correlations. Version 9.2 of SAS and version 11 of SigmaStat were used to analyze the data. Statistical significance was defined by P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Generation of mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency.

A transgenic construct including a neocassette flanked by two FRT sites (34 bp FLP recombinase target) was transfected into embryonic stem cells (Fig. 1A). Embryonic stem cells were selected for homologous recombination by G418 resistance, and the recombination was confirmed by either PCR or Southern blot analyses (data not shown). Homologous recombinant stem cells were injected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice to obtain mice with loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the AGT gene. To remove the neocassette, mice were bred to C57BL/6J mice expressing FRT recombinase that excised the DNA sequence located between the 2 FRT sites. After excision, a single FRT site remained. Female aP2-Cre0/0 Agtfl/fl mice were bred to male aP2-Cre1/0 Agtfl/fl transgenic male mice to generate littermates that were either wild-type for floxed alleles (Agtfl/fl) or adipocyte AGT deficient (AgtaP2).

To confirm effective and cell-selective deletion of AGT in adipocytes, DNA was genotyped (Fig. 1B), and mRNA abundance of AGT was quantified in different tissues using RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). Abundance of AGT mRNA was markedly and significantly reduced (by 90%) in RPF, EF, Subc, and BAT (Fig. 1C; P < 0.05). In contrast, AGT mRNA abundances were not significantly different between genotypes in liver, kidney, brain, or heart (Fig. 1C; P > 0.05) of Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice. To confirm efficiency of AGT protein deletion in adipocytes, we differentiated adipocytes from the stromal vascular fraction of subcutaneous adipose tissue. To assess the extent of adipocyte differentiation, we quantified mRNA abundance of aP2 on days 0 and 8 of differentiation. Abundance of aP2 mRNA was significantly increased on day 8 compared with day 0 (P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in aP2 mRNA abundance between genotypes (Fig. 2A). Similar to previous studies demonstrating increased AGT mRNA abundance in differentiating adipocytes (26), AGT mRNA abundance also increased from day 0 to day 8 of differentiation, but was markedly reduced in adipocytes differentiated from AgtaP2 compared with Agtfl/fl mice (Fig. 2B; P < 0.05). In addition, secretion of AGT from adipocytes differentiated from Agtfl/fγ mice increased significantly during the course of differentiation (Fig. 2C; P < 0.01). In contrast, AGT secretion from adipocytes differentiated from AgtaP2 mice was significantly reduced (by 72% on day 8; P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

AGT mRNA and protein are markedly reduced in adipocytes differentiated from stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue from mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency. A: mRNA abundance of aP2 in preadipocytes (day 0) and at day 8 of adipocyte differentiation. B: mRNA abundance of AGT in preadipocytes (day 0) and at day 8 of adipocyte differentiation. C: quantification of AGT protein secreted from stromal vascular fraction cells undergoing adipocyte differentiation. Data are means ± SE from n = 3–7 mice/genotype; *P < 0.05 compared with day 0 within genotype; **P < 0.05 compared with Agtfl/fl.

Adipocyte deficiency of AGT had no effect on body weight, fat mass, adipocyte size, or glucose homeostasis.

Body weight increased with increasing age in male (Table 1) and female mice (Table 2) of each genotype, with no significant differences between genotypes. Fat mass increased markedly with age in male and female mice of each genotype (Tables 1 and 2). Deficiency of AGT in adipocytes had no significant effect on fat mass at any age examined in male or female mice. Moreover, adipocytes from each genotype (12 mo of age) had similar morphologic appearance (Fig. 3A) and were not significantly different in size or cell number (Fig. 3, B and C) in male or female mice (data not shown). Plasma concentrations of leptin increased significantly with age in male and female mice (Tables 1 and 2), but were not significantly different between genotypes. Tissue weights of kidneys also increased significantly with age in both genotypes with no significant differences between genotypes. Fasting blood glucose was not significantly different at 2 or 12 mo of age in male Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice (Table 1). Glucose tolerance was not significantly influenced by deficiency of AGT in adipocytes at 2 or 12 mo of age in male or female mice (data not shown). In addition, plasma concentrations of insulin were not significantly different between genotypes in male (Table 1) or female mice (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of male Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice at 2 and 12 mo of age

| 2 mo |

12 mo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agtfl/fl | AgtaP2 | Agtfl/fl | AgtaP2 | |

| Body weight, g | 24.6 ± 2.1 | 24.9 ± 2.1 | 38.1 ± 1.6* | 36.7 ± 1.2* |

| Fat mass, % | 9.3 ± 2.6 | 8.1 ± 2.6 | 21.1 ± 2.2* | 19.9 ± 2.1* |

| Kidney, g | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.52 ± 0.02* | 0.54 ± 0.02* |

| Liver, g | 1.40 ± 0.09 | 1.44 ± 0.09 | 1.63 ± 0.06 | 1.61 ± 0.05 |

| FG, mg/100 ml | 201 ± 12 | 206 ± 12 | 175 ± 10* | 167 ± 7* |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 13.6 ± 2.7* | 8.6 ± 1.7* |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.11* | 0.52 ± 0.06* |

Data are means ± SE; n = 6 mice/group (2 mo), or n = 11–19 mice/group (12 mo). FG, fasting blood glucose.

P < 0.05 compared to 2 mo within genotype.

Table 2.

Characteristics of female Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice at 2 and 12 mo of age

| 2 mo |

12 mo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agtfl/fl | AgtaP2 | Agtfl/fl | AgtaP2 | |

| Body weight, g | 21.5 ± 1.5 | 21.6 ± 2.1 | 31.3 ± 1.0* | 29.2 ± 1.0* |

| Fat mass, % | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 0.10 | 18.7 ± 3.1* | 16.1 ± 1.5* |

| Kidney, g | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.01* | 0.32 ± 0.01* |

| Liver, g | 1.23 ± 0.10 | 1.22 ± 0.14 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | 1.25 ± 0.07 |

| FG, mg/100 ml | 180 ± 11 | 175 ± 16 | 126 ± 7* | 150 ± 8* |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 2.4* | 8.8 ± 0.6* |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.10 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.09 |

Data are means ± SE; n = 3–6 mice/group (2 mo), or n = 13–14 mice/group (12 mo).

P < 0.05 compared to 2 mo within genotype.

Fig. 3.

Adipocyte morphology (A), size (B), and number (C) in gonadal adipose tissue from Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice. A: adipocyte morphology in gonadal adipose tissue from mice of each genotype (12 mo of age). B: quantification of adipocyte size in gonadal adipose tissue from mice of each genotype (12 mo of age). C: quantification of adipocyte cell number in gonadal adipose tissue from mice of each genotype (12 mo of age). Data are means ± SE from n = 3 mice/genotype.

Adipocyte deficiency of AGT reduced plasma AGT concentrations and systolic blood pressure in 2- and 12-mo-old mice.

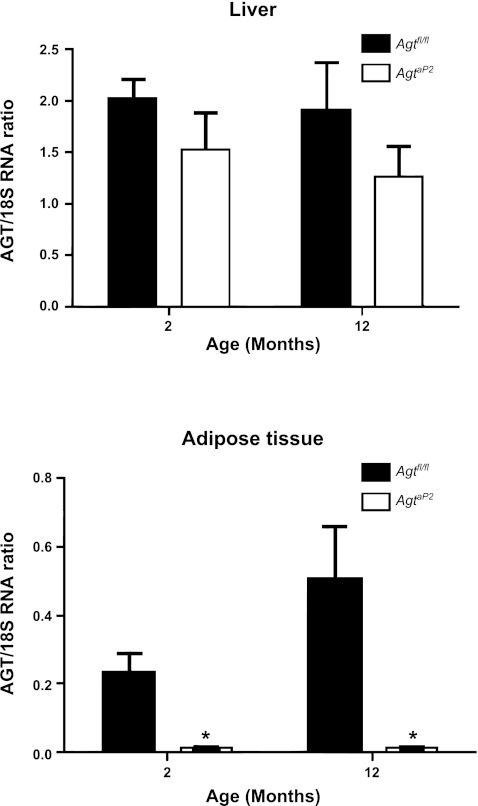

AGT mRNA abundance in livers of male mice was not significantly influenced by age or by genotype (Fig. 4A; P > 0.05). In RPF of male mice, AGT mRNA abundance was significantly reduced in mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency at 2 and 12 mo of age compared with Agtfl/fl age-matched controls (Fig. 4B; P < 0.05). However, there was no significant effect of age on AGT mRNA abundance in RPF.

Fig. 4.

AGT mRNA abundance in liver (A) and adipose tissue (B) from Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice. A: AGT mRNA abundance in livers from mice of each genotype at 2 and 12 mo of age. B: AGT mRNA abundance in RPF from mice of each genotype at 2 and 12 mo of age. Data are means ± SE from n = 5–6 mice/genotype/age; *P < 0.05 compared with Agtfl/fl within age group.

There was a significant main effect of age (P < 0.001), genotype (P < 0.05), and gender (P < 0.05) on SBP (Fig. 5A). Female mice of both genotypes exhibited significantly reduced SBP compared with age-matched males (Fig. 5A; P < 0.05). In addition, SBP was lower in 12-mo-old male and female mice, regardless of genotype, compared with 2-mo-old mice. Deficiency of AGT in adipocytes resulted in a significant reduction of SBP in male and female mice at 2 and 12 mo of age (Fig. 5A, P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Systolic blood pressures (SBP; A) and plasma AGT concentrations (B) in male and female Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice. A: SBPs in male and female Agtfl/fl and Agtap2 mice at 2 and 12 mo of age. B: plasma AGT concentrations in male and female Agtfl/fl and AgtaP2 mice at 2 and 12 mo of age. Data are means ± SE from n = 3–12 mice/genotype/gender/age; *P < 0.05 compared with Agtfl/fl within gender and age group; **P < 0.05 compared with 2 mo within genotype and gender; #P < 0.05 compared with males within genotype and age.

There was a significant main effect of age (P < 0.01) and genotype (P < 0.001), but no effect of gender (P > 0.05) on plasma AGT concentrations (Fig. 5B). Plasma AGT concentrations increased significantly with age (P < 0.001) in both male and female mice regardless of genotype. At 2 and 12 mo of age, plasma AGT concentrations were significantly decreased in AgtaP2 male and female mice compared with control littermates (Fig. 5B, P < 0.001).

Since adipose tissue mass increased markedly with increasing age in both genotypes (see Table 1), we correlated adipose tissue mass to SBP for all groups and factors (Fig. 6). The linear regression model demonstrated a significant negative correlation between SBP and percent fat mass (estimated coefficient: −0.308, P < 0.05) but not for AGT (estimated coefficient: 0.137, P > 0.05). The negative correlation between SBP and percent fat mass persisted when the analyses was restricted to mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency (P < 0.05), whereas no significant correlation was present between SBP and percent body fat in littermate controls (P > 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Negative correlation between % fat mass and SBP. There was a significant (P < 0.05) negative correlation between % fat mass and SBP when data from both genotypes and genders were pooled.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that adipocyte-specific AGT deficiency influences the systemic RAS and blood pressure in mice. Our results demonstrate that mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency exhibit marked reductions in adipose AGT mRNA abundance and decreased AGT secretion from adipocytes. We studied mice at 2 and 12 mo of age, contrasted by marked increases in adipose tissue mass during normal physiological aging. At 2 or 12 mo of age, plasma AGT concentrations and systolic blood pressures were reduced by adipocyte deficiency of AGT in male and female mice. These results demonstrate that under normal physiological conditions, adipocyte-derived AGT contributes to systemic AGT concentrations and RAS-mediated blood pressure control.

Previous studies demonstrated that whole body deficiency of AGT in mice resulted in nondetectable systemic concentrations of AGT and markedly reduced systolic blood pressure (35). However, these results did not identify the contribution of different AGT-producing tissues to the profound effects of whole body AGT deficiency. Of note, increased plasma AGT concentrations raised blood pressure in rats (14), demonstrating the importance of systemic AGT for blood pressure control. Our results support a prominent role for adipose tissue as an important source for systemic AGT. In 2- or 12-mo-old male and female mice, deficiency of AGT in adipocytes resulted in a modest (ranging from 24–28%) but significant reduction in plasma AGT concentrations. In agreement with our results, previous findings using a different approach (expression of AGT restricted to adipose tissue) demonstrated that 20–30% of AGT in plasma originates from adipose tissue (16). Interestingly, as liver AGT expression remained unchanged in 2- versus 12-mo-old mice and was not altered in 12-mo-old mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency, these results suggest that liver-derived AGT was not able to compensate for adipocyte-derived reductions in systemic AGT concentrations in AgtaP2 mice.

Previous studies demonstrated that adipose and liver AGT mRNA abundance decreased in tissues from older compared with younger rats (1, 9). In the present study, AGT mRNA abundances were similar in liver and adipose tissue from wild-type mice at ages 2 and 12 mo. Differences between results from this study with previous data demonstrating age-dependent reductions in adipose AGT mRNA abundance include the species examined (rats in previous studies vs. mice in this study) and the ages of rodents under study (4- vs. 12- to 16-wk-old rats in previous studies vs. 8- and 52-wk-old mice in this study). In addition, since AGT mRNA abundance did not change with age in liver or adipose tissue from control mice, then reductions in systolic blood pressure with age in the present study were most likely unrelated to age-dependent changes in AGT mRNA expression.

In addition to profound effects of whole body AGT deficiency on plasma AGT concentrations and blood pressure control, previous studies demonstrated lower body weights in mice with whole AGT deficiency (17, 35). Moreover, mice with whole body AGT deficiency exhibited reduced adipose tissue mass and smaller adipocytes that were partially restored by transgenic overexpression of AGT in adipocytes. In this study, deficiency of endogenous AGT in adipocytes had no effect on body weight or adipose tissue mass in 2- or 12-mo-old male or female mice. Removal of endogenous AGT from adipocytes, with ∼80% of the protein remaining in the circulation from nonadipose sources most likely allowed for sufficient levels of ANG II to be produced systemically to regulate adipose growth. The literature suggesting a role for ANG II in adipose tissue growth and development is conflicting with studies demonstrating either an increase or decrease in adipocyte growth or differentiation depending on the cell culture system studied (2, 4, 5, 10–12, 15, 16, 25, 29) or the species examined (2, 10–12, 16, 18, 24). Results from this study indicate that removal of endogenous AGT from adipocytes is insufficient to exert pronounced effects on adipose tissue growth and the regulation of body weight.

A major finding of the present study is reductions in SBP at 2 and 12 mo of age in mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency. Given that systemic AGT concentrations were reduced in these mice, reductions in SBP most likely resulted from decreased activity of the systemic RAS. This finding is in agreement with results from studies using mice with genetic deletion of other components of the RAS. Mice with whole body deficiency of AGT (35), renin (31, 34), angiotensin type 1a receptors (AT1aR) (20, 33, 36), combined AT1aR/AT1bR deficiency or angiotensin converting enzyme (7), exhibit low blood pressure. Moreover, a transgenic model expressing an antisense against AGT in the brain of rats exhibited reduced blood pressure (28). Our results are the first to demonstrate that reductions in endogenous AGT specifically in adipocytes also reduces blood pressure in mice, supporting a role for the adipocyte RAS in blood pressure control.

To understand the effect of adipocyte AGT deficiency on blood pressure, we correlated SBP to adipose tissue mass in mice of each genotype. The negative correlation between percent body fat and SBP, which persisted when the analyses was restricted to mice with adipocyte AGT deficiency, suggests that as adipose mass increases with age it becomes an important source for systemic AGT and blood pressure control. Previous investigators demonstrated that SBP correlated positively to fat mass in rodents with varying levels of AGT, including hypertensive mice overexpressing AGT in adipose tissue (16). Our results extend previous findings by demonstrating that deficiency of endogenous AGT in adipocytes results in a negative relationship between adipose mass and SBP.

Perspectives and Significance

These results demonstrate that adipose tissue is an important source of AGT in the regulation of blood pressure in mice fed standard laboratory diet. Mice with deficiency of endogenous AGT in adipocytes exhibited significant reductions in plasma AGT concentrations and systolic blood pressure. This effect was present in 2-mo-old mice and persisted in 12-mo-old mice with increased fat mass as part of the normal aging process. The magnitude of the effect of adipocyte AGT deficiency to reduce plasma AGT concentrations (24–28% reduction) and systolic blood pressure (6–10 mmHg) is sufficient to reduce cardiovascular risk in humans (37). These findings implicate an important role for adipocyte-derived AGT in blood pressure control in normal physiology. In addition, it is likely that in states of expanded fat mass, such as obesity, adipose-derived AGT may become an important pathophysiologic source of AGT as a link between obesity and hypertension. These results suggest that strategies that limit the expression of AGT in adipose tissue may be a novel and important pathway in the prevention and/or treatment of hypertension.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32-HL-091812 (to F. Yiannikouris), R01-HL-073085 (to L. A. Cassis) and P20-RR-021954 (to L. A. Cassis).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.Y. and L.A.C. conception and design of research; F.Y., M.K., V.L.E., and D.L.R. performed experiments; F.Y., R.C., and L.A.C. analyzed data; F.Y., R.C., and L.A.C. interpreted results of experiments; F.Y. and L.A.C. prepared figures; F.Y. and L.A.C. drafted manuscript; F.Y., R.C., A.D., and L.A.C. edited and revised manuscript; F.Y., M.K., R.C., V.L.E., D.L.R., A.D., and L.A.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance for tissue morphology of Wendy Katz.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams F, Wiedmer P, Gorzelniak K, Engeli S, Klaus S, Boschmann M. Age-related changes of renin-angiotensin system genes in white adipose tissue of rats. Horm Metab Res 34: 716–720, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brucher R, Cifuentes M, Acuna MJ, Albala C, Rojas CV. Larger anti-adipogenic effect of angiotensin II on omental preadipose cells of obese humans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15: 1643–1646, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cassis LA, Lynch KR, Peach MJ. Localization of angiotensinogen messenger RNA in rat aorta. Circ Res 62: 1259–1262, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crandall DL, Armellino DC, Busler DE, McHendry-Rinde B, Kral JG. Angiotensin II receptors in human preadipocytes: role in cell cycle regulation. Endocrinology 140: 154–158, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Darimont C, Vassaux G, Ailhaud G, Negrel R. Differentiation of preadipose cells: paracrine role of prostacyclin upon stimulation of adipose cells by angiotensin-II. Endocrinology 135: 2030–2036, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Antagonism of AT2 receptors augments angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol 134: 865–870, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Esther CR, Jr, Howard TE, Marino EM, Goddard JM, Capecchi MR, Bernstein KE. Mice lacking angiotensin-converting enzyme have low blood pressure, renal pathology, and reduced male fertility. Lab Invest 74: 953–965, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frederich RC, Jr, Kahn BB, Peach MJ, Flier JS. Tissue-specific nutritional regulation of angiotensinogen in adipose tissue. Hypertension 19: 339–344, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harp JB, DiGirolamo M. Components of the renin-angiotensin system in adipose tissue: changes with maturation and adipose mass enlargement. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 50: B270–B276, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Janke J, Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Luft FC, Sharma AM. Mature adipocytes inhibit in vitro differentiation of human preadipocytes via angiotensin type 1 receptors. Diabetes 51: 1699–1707, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Janke J, Schupp M, Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Boschmann M, Sauma L, Nystrom FH, Jordan J, Luft FC, Sharma AM. Angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonists induce human in-vitro adipogenesis through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activation. J Hypertens 24: 1809–1816, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones BH, Standridge MK, Moustaid N. Angiotensin II increases lipogenesis in 3T3–L1 and human adipose cells. Endocrinology 138: 1512–1519, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karlsson C, Lindell K, Ottosson M, Sjostrom L, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM. Human adipose tissue expresses angiotensinogen and enzymes required for its conversion to angiotensin II. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 3925–3929, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klett CP, Granger JP. Physiological elevation in plasma angiotensinogen increases blood pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1437–R1441, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mallow H, Trindl A, Loffler G. Production of angiotensin II receptors type one (AT1) and type two (AT2) during the differentiation of 3T3–L1 preadipocytes. Horm Metab Res 32: 500–503, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Massiera F, Bloch-Faure M, Ceiler D, Murakami K, Fukamizu A, Gasc JM, Quignard-Boulange A, Negrel R, Ailhaud G, Seydoux J, Meneton P, Teboul M. Adipose angiotensinogen is involved in adipose tissue growth and blood pressure regulation. FASEB J 15: 2727–2729, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Massiera F, Seydoux J, Geloen A, Quignard-Boulange A, Turban S, Saint-Marc P, Fukamizu A, Negrel R, Ailhaud G, Teboul M. Angiotensinogen-deficient mice exhibit impairment of diet-induced weight gain with alteration in adipose tissue development and increased locomotor activity. Endocrinology 142: 5220–5225, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matsushita K, Wu Y, Okamoto Y, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Local renin angiotensin expression regulates human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to adipocytes. Hypertension 48: 1095–1102, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McClain D. Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Testing (IPGTT). Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium (AMDCC). http://www.diacomp.org/shared/showFile.aspx?doctypeid=3&docid=11.

- 20. Oliverio MI, Best CF, Kim HS, Arendshorst WJ, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Angiotensin II responses in AT1A receptor-deficient mice: a role for AT1B receptors in blood pressure regulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 272: F515–F520, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pinterova L, Krizanova O, Zorad S. Rat epididymal fat tissue express all components of the renin-angiotensin system. Gen Physiol Biophys 19: 329–334, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rebrin I, Sohal RS. Comparison of thiol redox state of mitochondria and homogenates of various tissues between two strains of mice with different longevities. Exp Gerontol 39: 1513–1519, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodbell M. Localization of lipoprotein lipase in fat cells of rat adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 239: 753–755, 1964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saint-Marc P, Kozak LP, Ailhaud G, Darimont C, Negrel R. Angiotensin II as a trophic factor of white adipose tissue: stimulation of adipose cell formation. Endocrinology 142: 487–492, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sarzani R, Marcucci P, Salvi F, Bordicchia M, Espinosa E, Mucci L, Lorenzetti B, Minardi D, Muzzonigro G, Dessi-Fulgheri P, Rappelli A. Angiotensin II stimulates and atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits human visceral adipocyte growth. Int J Obes (Lond) 32: 259–267, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saye JA, Cassis LA, Sturgill TW, Lynch KR, Peach MJ. Angiotensinogen gene expression in 3T3–L1 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 256: C448–C451, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saye JA, Ragsdale NV, Carey RM, Peach MJ. Localization of angiotensin peptide-forming enzymes of 3T3–F442A adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C1570–C1576, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schinke M, Baltatu O, Bohm M, Peters J, Rascher W, Bricca G, Lippoldt A, Ganten D, Bader M. Blood pressure reduction and diabetes insipidus in transgenic rats deficient in brain angiotensinogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 3975–3980, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schling P, Loffler G. Effects of angiotensin II on adipose conversion and expression of genes of the renin-angiotensin system in human preadipocytes. Horm Metab Res 33: 189–195, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schling P, Mallow H, Trindl A, Loffler G. Evidence for a local renin angiotensin system in primary cultured human preadipocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23: 336–341, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharp MG, Fettes D, Brooker G, Clark AF, Peters J, Fleming S, Mullins JJ. Targeted inactivation of the Ren-2 gene in mice. Hypertension 28: 1126–1131, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shenoy U, Cassis L. Characterization of renin activity in brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C989–C999, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sugaya T, Nishimatsu S, Tanimoto K, Takimoto E, Yamagishi T, Imamura K, Goto S, Imaizumi K, Hisada Y, Otsuka A, Uchida H, Sugiura M, Fukuta K, Fukamizu A, Murakami K. Angiotensin II type 1a receptor-deficient mice with hypotension and hyperreninemia. J Biol Chem 270: 18719–18722, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanimoto K, Sugiura A, Kanafusa S, Saito T, Masui N, Yanai K, Fukamizu A. A single nucleotide mutation in the mouse renin promoter disrupts blood pressure regulation. J Clin Invest 118: 1006–1016, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanimoto K, Sugiyama F, Goto Y, Ishida J, Takimoto E, Yagami K, Fukamizu A, Murakami K. Angiotensinogen-deficient mice with hypotension. J Biol Chem 269: 31334–31337, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsuchida S, Matsusaka T, Chen X, Okubo S, Niimura F, Nishimura H, Fogo A, Utsunomiya H, Inagami T, Ichikawa I. Murine double nullizygotes of the angiotensin type 1A and 1B receptor genes duplicate severe abnormal phenotypes of angiotensinogen nullizygotes. J Clin Invest 101: 755–760, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turnbull F. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet 362: 1527–1535, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]