Abstract

Impaired renal function with loss of nephron number in chronic renal disease (CKD) is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. However, the structural and functional cardiac response to early and mild reduction in renal mass is poorly defined. We hypothesized that mild renal impairment produced by unilateral nephrectomy (UNX) would result in early cardiac fibrosis and impaired diastolic function, which would progress to a more global left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. Cardiorenal function and structure were assessed in rats at 4 and 16 wk following UNX or sham operation (Sham); (n = 10 per group). At 4 wk, blood pressure (BP), aldosterone, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), proteinuria, and plasma B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) were not altered by UNX, representing a model of mild early CKD. However, UNX was associated with significantly greater LV myocardial fibrosis compared with Sham. Importantly, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining revealed increased apoptosis in the LV myocardium. Further, diastolic dysfunction, assessed by strain echocardiography, but with preserved LVEF, was observed. Changes in genes related to the TGF-β and apoptosis pathways in the LV myocardium were also observed. At 16 wk post-UNX, we observed persistent LV fibrosis and impairment in LV diastolic function. In addition, LV mass significantly increased, as did LVEDd, while there was a reduction in LVEF. Aldosterone, BNP, and proteinuria were increased, while GFR was decreased. The myocardial, structural, and functional alterations were associated with persistent changes in the TGF-β pathway and even more widespread changes in the LV apoptotic pathway. These studies demonstrate that mild renal insufficiency in the rat results in early cardiac fibrosis and impaired diastolic function, which progresses to more global LV remodeling and dysfunction. Thus, these studies importantly advance the concept of a kidney-heart connection in the control of myocardial structure and function.

Keywords: kidney, heart failure, remodeling, nephrectomy, natriuretic peptides

increasing evidence from human studies underscores an interaction between the kidney and heart, in which impairment of one organ contributes to progressive and combined failure of both organs. This concept is supported by both experimental and clinical investigations that have shown even mild renal impairment contributes to increased cardiovascular risk (4, 9, 15, 21, 25). Furthermore, in recent human studies using magnetic resonance imaging, very early renal disease characterized by mild increases in serum Cystatin C is associated with increased myocardial mass (23). The latter study raises the possibility that the heart may remodel early during the natural history of CKD.

In the current study, we sought to define LV structure and function in a model of mild renal insufficiency in rats 4 and 16 wk after removal of one kidney (UNX) to reduce nephron number. Specifically, we assessed myocardial structure with a special focus on fibrosis and employed microarray gene analysis of two key molecular pathways involved with cardiac fibrosis. As microarray analysis identified widespread changes in apoptotic pathway genes, we also assessed the presence of LV apoptosis. Finally, myocardial function was assessed by echocardiography. Our overall working hypothesis is that mild renal insufficiency results in early cardiac apoptosis and fibrosis with mild impairment in diastolic function and preserved early systolic function, which progresses to more global LV dysfunction and remodeling.

METHODS

Animals.

Male Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) 150–250 g (6 to 8 wk) were used (n = 10 per group). The experimental design was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Groups were as follows: group 1: Sham-4 wk, group 2: UNX-4 wk (groups 1 and 2 had acute studies performed 4 wk after sham or UNX surgery), group 3: Sham-16 wk, and group 4: UNX-16 wk (groups 3 and 4 had acute studies performed 16 wk after sham or UNX surgery). On day 1, animals were randomly assigned to the four different groups. The rats in the UNX group underwent a surgical procedure to remove the whole right kidney. The left kidney was undisturbed. The rats in the Sham group underwent the same procedure, but no kidney was removed.

Surgical procedure.

Laparotomy was performed under gas anesthesia (isoflurane 2%). The right kidney was carefully separated from the adrenal gland and the surrounding tissue (24). The renal artery and vein, as well as the ureter, were ligated with a 4.0 silk suture followed by removal of the right kidney.

Acute studies.

During weeks 4 and 16, the rats underwent an acute study using the same anesthesia. Conventional and two-dimensional (2D) speckle tracking echocardiography was performed prior to acute experiments to assess LV chamber and myocardial function and geometry. After echocardiography, polyethylene (PE)-50 tubing was placed into the carotid artery for blood pressure monitoring and blood sampling. The bladder was cannulated for urine collection. Inulin (2%) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in normal saline and PAH (1%) (Sigma) were then continuously infused into the jugular vein. After equilibration (60 min), a clearance study was performed. A 60-min urine collection was obtained with blood sampling at the end to calculate GFR and renal plasma flow from the clearance of inulin and PAH.

Blood for hormone analysis was placed in heparin or EDTA tubes on ice. It was analyzed for electrolytes, inulin, and hormones (BNP and aldosterone). After centrifugation at 2,500 rpm at 4°C for 10 min, plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until assay. Plasma BNP and aldosterone were determined by radioimmunoassay (22, 26). Plasma and urine concentrations for electrolytes were determined by flame photometer (model 1L943; Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA). Plasma and urine concentrations for inulin were measured by anthrone method for calculation of GFR. On the day prior to the acute experiment, rats were housed in a metabolic cage for 24-h measurement of urine and assessment of proteinuria.

In two additional subgroups of animals, Sham (n = 5) and UNX (n = 5), we assessed continuous blood pressure using a continuous telemetry device (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) a week before randomizing the animals to the two different groups.

Echocardiography studies: conventional echocardiography.

Ultrasonic scans were performed in all rats using a Vivid 7 system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with a 10S ultrasound probe (11.5 MHz) with ECG monitoring. M-mode images and grayscale 2D images (300–350 frames/s) of parasternal long-axis and mid-LV were recorded for off-line analysis. LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDd), diastolic septal wall thickness (SWTd), diastolic posterior wall thickness (PWTd), and systolic thicknesses were measured from M-mode images. LV mass was calculated according to uncorrected cube assumptions as LV mass = 1.055 × [(LVEDd + SWTd + PWTd)3 − (LVEDd)3]. End-systolic, end-diastolic, and stroke volumes, and ejection fraction (EF) were calculated using the Teichholz formula: LV volume = 7 × [(LVEDd)3/(2.4 + LVEDd)]. Relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated as RWT = (SWTd + PWTd)/LVEDd. All parameters represent the average of three beats.

Two-dimensional speckle-derived strain echocardiography.

Using EchoPAC software (EchoPAC PC, 2D strain, BTO 6.0.0, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), endocardial border was carefully manually traced at end-systole in LV short-axis views, and ideal width of circular region of interest was chosen to include the entire myocardial wall. Speckle tracking was performed by the software and global strain and strain rates parameters were measured (18, 19). The analysis included peak circumferential contraction strains (Cs-C) and strain rates Csr-C for evaluation of myocardial systolic function and peak early (Csr-E) and late relaxation (i.e., atrial contraction, Csr-A) circumferential strain rates, and their ratio for evaluation of myocardial diastolic function. All parameters represent the average of three beats.

Histological analysis.

Hearts and kidneys were harvested after the acute experiment. Sections of the left ventricle, renal cortex, and medulla were immersed in formalin for later histological analysis. The remaining tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for molecular analysis and microarray studies. Picrosirius red staining was utilized to assess collagen content. Glomerular volume measurements were performed to evaluate glomerular hypertrophy. For this purpose, the Weibel formula was used (13). An Axioplan II KS 400 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Munich, Germany) and KS 400 software were utilized to analyze the histological slides and to calculate the percentage of picrosirius red stain, as well as to determine glomerular volumes. TUNEL stain was performed with the CardioTACS in situ kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD).

Microarray studies.

Total RNA was isolated from snap-frozen left-ventricle, kidney cortex, and kidney medulla using the TRIzol method. Purified cDNA was used as a template for in vitro transcription reaction for the synthesis of biotinylated complementary RNA (cRNA) using an RNA transcript-labeling reagent (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Labeled cRNAs were then fragmented and hybridized onto the Affymetrix Rat GeneChip oligonucleotide array (Affymetrix GeneChip Rat Genome 230 2.0). Expression of genes in the UNX group samples was compared with the Sham group controls using GeneSifter (Seattle, WA) software. Microarray-based expression differences were confirmed with real-time RT-PCR. The genes utilized for this purpose were ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (microarray yielded a 4.62-fold decrease and qPCR a 4.96 fold decrease) and indolmethylamine N-methyltransferase (microarray yielded a 2.3-fold increase and qPCR a 3.4-fold increase). First-strand cDNA was generated using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed using the Lightcycler (Roche), and expression was normalized vs. GAPDH.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SE. The comparison between each measurement was performed by Student's t-test. Significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05. For gene microarray chip analysis, the software Genesifter was utilized. For overall analysis a P < 0.05 and a 1.5-fold change were used. For pathway analysis, a Z score greater than 2 was used.

RESULTS

Four Weeks Following Uninephrectomy

Renal and neurohumoral function.

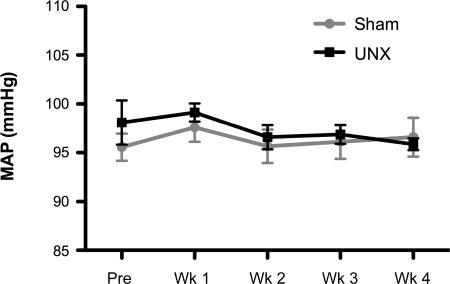

Four weeks after UNX, an increase in glomerular volume was observed consistent with glomerular hypertrophy (Sham: 1 ± 0.1, UNX: 1.6 ± 0.1%, P < 0.0001). Renal fibrosis was observed in both cortex (Sham: 1.06 ± 0.2, UNX: 4.24 ± 0.7%, P < 0.01) and medulla (Sham: 1.13 ± 0.3, UNX: 6.89 ± 2.1%, P < 0.05) with a trend toward a reduction in GFR (P = 0.06). There was no change in proteinuria or alterations in sodium or water excretion (Table 1). Compared with sham controls, we observed no differences in plasma BNP or aldosterone system in rats 4 wk following UNX (Table 1). Further, arterial pressure was not different between groups (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Cardiorenal and humoral data at 4 wk

| SHAM | UNX | |

|---|---|---|

| MBP, mmHg | 89.8 ± 2.5 | 92.5 ± 2.6 |

| GFR, ml/min | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| RBF, ml/min | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.6* |

| U Vol, ml/24 h | 22.5 ± 2.8 | 21.6 ± 2.2 |

| UNaV, mEq/24 h | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| U Prot, mg/24 h | 14.3 ± 2.8 | 11.2 ± 1.8 |

| BNP, pg/ml | 17.1 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 1.9 |

| cGMP, pg/ml | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 6.5 ± 0.6 |

| Aldosterone, ng/dl | 16.7 ± 3.2 | 30.4 ± 6.1 |

| PRA, ng·ml−1·h−1 | 30.2 ± 2.0 | 32.5 ± 1.1 |

All data are expressed as means ± SE. MBP, mean blood pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; RBF, renal blood flow; U Vol, urinary volume excretion; UNaV, urinary sodium excretion; U Prot, poretinuria; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; PRA, plasma renin activity. The comparison between each measurement was performed by t-test. Significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

Significantly different vs. sham.

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) assessed continuously by telemetry. Measurements were continuously taken and averaged at a week before performing unilateral nephrectomy (UNX) (Pre) and at weeks (Wk) 1, 2, 3, and 4. All data are expressed as means ± SE. The comparison between the two groups was done by two-way ANOVA, and each time point was compared between groups with Student's t-test. There was no statistical difference between groups.

LV structure.

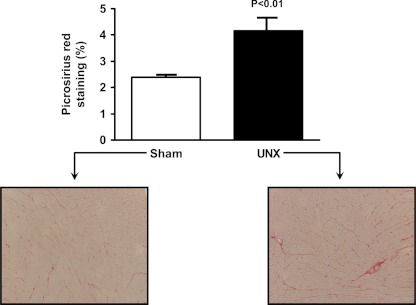

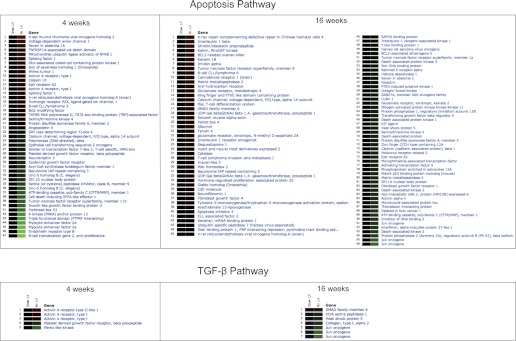

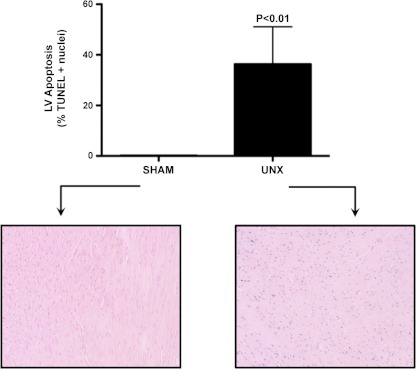

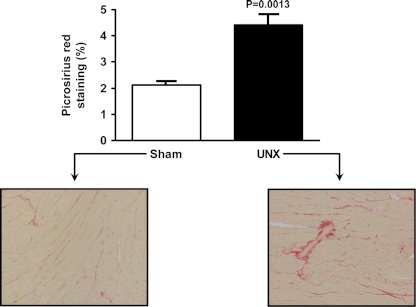

We next assessed structural changes in the LV following UNX. To assess cardiac fibrosis, we utilized Picrosirius red staining to quantitate collagen content in the LV (Fig. 2). Here, we observed a significant increase in interstitial and perivascular collagen in the UNX group compared with Sham. Consistent with increased LV fibrosis, microarray analysis of the LV myocardium demonstrated significant alterations in the apoptosis and TGF-β pathways, where 47 and 5 genes in each respective pathway were altered (1.5-fold, P < 0.05). Fig. 3 summarizes the 52 genes in these two pathways, which were significantly altered at 4 wk after UNX. Consistent with alterations in the apoptosis pathways, specific staining for apoptosis using the TUNEL assay in the LV myocardium demonstrated increased apoptosis following UNX (Sham: 0.2 ± 0.1, UNX: 36.3 ± 14.7%, P < 0.05). (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Left ventricular fibrosis at 4 wk is shown. (%) Representative graphic and histology (10×). Picrosirius red stain. Sham on left, UNX on right.

Fig. 3.

Left ventricular gene microarray of Sham and UNX. Apoptosis and TGF-β-related genes are altered at 4 and 16 wk after UNX. (Genesifter Software, Geospiza, Seattle, WA) Red color denotes increased expression of the gene, and green color denotes decreased expression compared with Sham. Apoptosis-related genes (4 wk): genes 1 to 22 have increased its expression, while genes 23 to 47 have decreased its expression in the LV of the UNX group compared with Sham group. TGF-β-related genes (4 wk): Genes 1 to 3 have increased its expression, while genes 4 and 5 have decreased its expression in the LV of the UNX group compared with Sham. Apoptosis-related genes (16 wk): Genes 1 to 41 have increased its expression, while genes 42 to 96 have decreased its expression in the LV of the UNX group compared with Sham. TGF-β-related genes (16 wk): Gene 1 has increased its expression, while genes 2 to 7 have decreased its expression in the LV of the UNX group compared with Sham.

Fig. 4.

Left ventricular apoptosis at 4 wk. [terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL), Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD]. Sham and UNX. Blue color reveals TUNEL-positive nuclei. Sham on left, UNX on right.

Echocardiography.

Functional and structural LV assessment was performed using conventional and speckle-strain echocardiographic data (Table 2). Diastolic septal wall thickness (SWTd), as well as diastolic posterior wall thickness (PWTd) were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in UNX, resulting in lower (P < 0.05) RWT. LV systolic chamber function as assessed with LVEF, systolic myocardial function as measured by peak Cs-C and strain rate (Csr-C), as well as LV mass, were not different between the groups. Early diastolic strain rate (Csr-E) was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the UNX group, while late relaxation (atrial contraction) circumferential strain rates (Csr-A) increased, resulting in a decreased Csr-E/A ratio consistent with mild myocardial diastolic impairment.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic profile at 4 wk

| SHAM | UNX | |

|---|---|---|

| HR, bpm | 377 ± 21 | 395 ± 41 |

| SWTd, mm | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1* |

| PWTd, mm | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1* |

| LVEDd, mm | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 7.6 ± 0.3 |

| RWT | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.02* |

| EF, % | 77 ± 4 | 77 ± 2 |

| LV mass, g | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 0.79 ± 0.08 |

| Cs-C, % | 17.3 ± 1.9 | 16.5 ± 2.0 |

| Csr-C, s−1 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.5 |

| Csr-E, s−1 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 1.1* |

| Csr-A, s−1 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 1.1* |

| Csr-E/A | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.4* |

HR, heart rate; SWTd, diastolic septal wall thickness; PWTd, diastolic posterior wall thickness; LVEDd, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; RWT, relative wall thickness; EF, ejection fraction; LV mass, left ventricular mass; Cs-C, peak circumferential contraction strain; Csr-C, peak circumferential contraction strains rate; Csr-E, early diastolic strain rate; Csr-A, late relaxation circumferential strain rate; Csr-E/A, early diastolic strain rate/ late relaxation circumferential strain rate ratio. All data are expressed as means ± SE. The comparison between each measurement was performed by t-test. Significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

Significantly different vs. sham.

Sixteen Weeks Following Uninephrectomy

Renal and neurohumoral function.

Sixteen weeks after UNX, renal cortical and medullary fibrosis was similar between the sham group and the UNX group, although there was a strong trend for greater collagen content in the medulla in the UNX group. GFR was, however, reduced compared with sham (Sham: 3.3 ± 0.5, UNX: 1.6 ± 0.3 ml/min, P < 0.01), as well as a trend for RBF to decrease [Sham: 6.55 ± 1.5, UNX: 5.26 ± 0.8 ml/min, not significant (NS); P = 0.4] (Table 3). Moreover, at 16 wk, we now observed a significant increase in proteinuria compared with sham (Sham: 16.2 ± 3.8, UNX: 95.9 ± 33.8 mg/24 h, P < 0.05) with no alterations in sodium or water excretion (Table 3). Compared with sham controls, there was an increase in plasma BNP (Sham: 8.04 ± 0.3, UNX: 10.13 ± 0.7 pg/ml, P < 0.01) and aldosterone (Sham: 20.93 ± 3.2, UNX: 44.2 ± 7 ng/dl, P < 0.01) in rats 16 wk following UNX. Arterial pressure was not different between groups. (Sham: 87.7 ± 3.4, UNX: 80.7 ± 4.0%, NS) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiorenal and humoral data at 16 wk

| SHAM | UNX | |

|---|---|---|

| MBP, mmHg | 87.7 ± 3.4 | 80.7 ± 4.0 |

| GFR, ml/min | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.3* |

| RBF, ml/min | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 0.8 |

| U Vol, ml/24 h | 18.1 ± 1.2 | 25.6 ± 6.7 |

| UNaV, mEq/24 h | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| U Prot, mg/24 h | 16.2 ± 3.8 | 95.9 ± 33.8 |

| BNP, pg/ml | 8.04 ± 0.3 | 10.1 ± 0.7* |

| cGMP, pg/ml | 6.9 ± 1 | 12.2 ± 1.3* |

| Aldosterone, ng/dl | 20.9 ± 3.2 | 44.2 ± 7* |

| PRA, ng·ml−1·h−1 | 17.7 ± 0.8 | 19.0 ± 0.3 |

All data are expressed as means ± SE. The comparison between each measurement was performed by t-test. Significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

Significantly different vs. sham.

LV structure.

Picrosirius red staining revealed that the cardiac fibrosis seen at 4 wk persisted at 16 wk (Sham: 2.1 ± 0.1, UNX: 4.4 ± 0.4%, P < 0.01) (Fig. 5). This fibrosis was interstitial, as well as perivascular in the UNX group compared with Sham. Microarray analysis of the apoptotic and TGF-β pathways of the LV myocardium 16 wk after UNX revealed that 96 and 7 genes in each respective pathway were changed (1.5-fold, P < 0.05). Figure 3 reports these 103 genes, which were changed in these two pathways at 16 wk between groups. Of note, the alterations in the apoptosis pathway observed at 4 wk after UNX was more widespread at 16 wk. Also, at 16 wk, some other important genes showed increased activation compared with UNX at 4 wk (P < 0.05): IL-6 (marker for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) (UNX-0–4 wk: 8.4 ± 0.2 vs. UNX-16 wk: 10.2 ± 0.1), transforming growth factor beta 2 (TGF-β2) (UNX-4 wk: 4.5 ± 0.2 vs. UNX-16 wk: 6 ± 0.3), and connective tissue growth factor (UNX-4 wk: 9.9 ± 0.1 vs. UNX-16 wk: 11.2 ± 0.3) (both involved in increased collagen deposition and alteration of cardiac contraction).

Fig. 5.

Left ventricular fibrosis at 16 wk. (%) Representative graphic and histology (10×). Picrosirius red stain. Sham on left, UNX on right.

Echocardiography.

Table 4 reports echocardiographic data. At 16 wk, there was no difference in SWTd, while PWTd was significantly higher in UNX-16-wk group as was LVEDd. Importantly, and in contrast to 4 wk following UNX, at 16 wk following UNX, LVEF was decreased compared with Sham. Cs-C and Csr-C were significantly lower in UNX group, and in contrast to 4 wk post-UNX, LV mass was now significantly higher. Thus, at 16 wk, there is reduction in systolic function associated with ventricular hypertrophy, which was not present at 4 wk after UNX. As observed at 4 wk, early diastolic strain rate (Csr-E) was also significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the UNX group, while late relaxation (atrial contraction) Csr-A increased, resulting in a decreased Csr-E/A ratio consistent with mild myocardial diastolic impairment.

Table 4.

Echocardiographic profile at 16 wk

| Sham | UNX | |

|---|---|---|

| HR, bpm | 377 ± 26 | 382 ± 22 |

| SWTd, mm | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| PWTd, mm | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1* |

| LVEDd, mm | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 0.7* |

| RWT | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.04 |

| EF, % | 79 ± 4 | 74 ± 2* |

| LV mass, g | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 1.32 ± 0.19* |

| Cs-C, % | 18.1 ± 1.9 | 13.6 ± 1.6* |

| Csr-C, s−1 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.4* |

| Csr-E, s−1 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 0.6* |

| Csr-A, s−1 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.7 |

| Csr-E/A | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.3* |

All data are expressed as means ± SE. The comparison between each measurement was performed by t-test. Significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

Significantly different vs. sham.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of the current study is that mild CKD, produced by UNX, results in early cardiac fibrosis with mild diastolic impairment and preserved systolic function at 4 wk after UNX. These findings seem to be independent of significant increase in blood pressure (BP), sodium, or water retention, or activation of aldosterone. Importantly, cardiac hypertrophy and impairment of heart function progress over time (16 wk). While structural changes in the heart are not associated with activation of aldosterone at 4 wk, they are characterized by a late (16 wk) activation of aldosterone. This kidney-heart connection in mild early CKD may involve at least two important gene pathways, as evidenced in our study, by alterations in the TGF-β and apoptotic pathways. Indeed, at 4 wk after UNX, the observed fibrotic response of the heart is associated with evidence for increased myocardial apoptosis. Altogether, these findings indicate that reduction of renal mass is characterized by early and late structural and functional modifications accompanied by gene pathway alterations and hormonal profibrotic factor activation, such as aldosterone at 16 wk.

There are likely multiple mechanisms by which UNX may mediate early myocardial fibrosis. While it is increasingly noted that aldosterone mediates cardiac fibrosis (1, 2, 14), in the current study, there is no activation of aldosterone at 4 wk, which is, however, elevated at 16 wk. Other possible mechanisms that may contribute to the early fibrosis observed in this study can be related to the TGF-β and apoptosis pathways (17, 27). Therefore, we sought to determine the extent of perturbation of these two pathways by assessing changes in their related genes by microarray analysis in the LV myocardium. After 4 wk from UNX, when mild cardiac fibrosis and impairment in diastolic function, as assessed by echo-strain analysis, are present, both TGF-β and apoptosis pathways exhibited numerous gene changes. Furthermore, these apoptotic gene alterations are associated with TUNEL-positive staining, demonstrating a significant increase in apoptosis after 4 wk of UNX. While our goal was not to identify the specific mechanisms, our study provides direction for further investigations to understand the myocardial response to mild early renal insufficiency. We would speculate that the remaining kidney, which itself is undergoing remodeling, as demonstrated by the increase in glomerular volume and fibrosis, may release humoral factors, yet to be defined, which induce TGF-β and apoptotic pathways in the heart. Alternatively, a systemic inflammatory process could occur, which may also contribute to myocardial fibrosis and myocyte death.

Of note, even though LV fibrosis does not progress from 4 to 16 wk, there is a worsening of cardiac function, as well as an increase of LV mass at 16 UNX vs. 4 UNX. Although, we cannot account for an increase in fibrosis to explain the progressive worsening of cardiac function at 16 wk, we observed an alteration of other important genes associated with myocardial dysfunction that are not yet activated at 4 wk. These genes are IL-6, a known marker of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and TGF-β2 and connective tissue growth factor (both involved in increased collagen deposition and alteration of cardiac contraction). These genes could possibly be relevant in understanding the mechanisms of progression of cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy of this model in time.

At 16 wk, LV mass increases and LVEF modestly but significantly decreases compared with Sham. Further, there is a modest but significant increase in LVEDd, together with an increase in plasma BNP, consistent with both LVH and myocardial stretch. In addition to continued diastolic impairment, strain analysis demonstrates systolic impairment. Specifically, Cs-C and Csr-C are both reduced 16 wk after UNX. This progressive cardiac remodeling paralleled progressive renal impairment. GFR is significantly reduced, although moderately (50% lower than Sham), and proteinuria is also present. There are, however, no signs of sodium and water retention, as sodium and water excretion are not different in the UNX compared with the Sham group.

Although we do not observe activation at 4 wk, aldosterone is activated 16 wk post-UNX. The current study was designed to detect the presence of possible cardiac structural and functional changes at 4 and 6 wk post-UNX; thus, we cannot exclude that an early, yet transient, activation of aldosterone occurs immediately after surgery, returning to normal range by week 4. Indeed, an early and transient activation of aldosterone could also contribute to the presence of fibrosis at 4 wk. Further studies are needed to investigate possible early activation of aldosterone. The activation of aldosterone at 16 wk without marked sodium and water retention is consistent with the phenomenon of mineralocorticoid escape (3, 8). Specifically, the kidney escaped from the sodium-retaining properties of aldosterone excess, as we previously demonstrated in a canine model of mild LV dysfunction (8). Relevant to this pathological role of aldosterone in this model of mild CKD is the study by Edwards et al. (12) that have recently demonstrated using magnetic resonance imaging that spironolactone, in patients with early mild CKD, resulted in a reduced LVH in association with a reduction in proteinuria. With the report too of a mortality benefit in the recently reported findings from the EMPHASIS trial (29), in which epleronone was given to humans with mild HF, an important cardiorenal protective role for aldosterone antagonism warrants further investigation in the setting of early CKD, although the problem of hyperkalemia could be a limiting factor.

Although we investigated several possible pathways of the kidney-heart connection (aldosterone, BNP, gene pathways), the mechanisms of such interaction remain not completely understood. A limitation of the current study is that we did not assess LV end-diastolic pressure to more invasively assess LV pressure and pressure/volume relationships, which should be considered in future studies. Also, this study shows a very minor increase in BNP levels at 16 wk in the UNX group compared with Sham. The lack of activation of BNP in this study is consistent to the findings by Cataliotti et al. (6). Indeed, in this study, the authors showed the lack of activation of BNP in patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Further studies measuring atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) in this setting are needed to determine whether this is a better marker than BNP for cardiac volume overload. Indeed, a possible elevation of ANP could explain the activation of cGMP and the lack of progression of cardiac fibrosis at 16 wk.

Our findings are consistent with the clinical observations of Edwards et al. (10, 12), which reported that patients with mild renal insufficiency have cardiovascular adaptations similar to patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Other possible mechanisms involved in the renocardiac connection are starting to emerge. One of such mechanisms was recently reported by Cappola et al. (5), who described a genetic variant in the CLCNKa chloride channel (present only in the kidney), which was implicated in increased risk for heart failure. Even though in the present study, we did not find a significant change in that gene between groups, this is clear evidence that a kidney-heart connection also exists in humans.

Perspectives and Significance

Our findings have important clinical implications, which are supported by recent and ongoing epidemiological investigations (7, 11, 12, 23). In a community-based cohort, we observed that the prevalence of mild chronic renal insufficiency (i.e., calculated GFR < 60 ml/min) was 23% (7). Importantly, those with reduced GFR were characterized by a greater prevalence of HF and greater structural remodeling of the heart compared with subjects with normal GFR. Indeed, in a further study involving normal subjects, as well as subjects with hypertension and diastolic dysfunction, GFR was the strongest predictor for concentric hypertrophy, independent of BP (20). In the seminal report from the Dallas Heart Study, subjects with an elevated serum cystatin C, reflecting a reduction in renal function, had demonstrable BP-independent changes in myocardial structure with increased LV mass (23). Such clinical observations support the speculation that impaired kidney function is associated with release of factors (humoral and/or cellular) from the kidney that contribute to changes in myocardial function and structure. Cardiac remodeling and hypertrophy are known to be important risk factors in humans with ESRD (30–32); thus, our findings have important clinical implications because of the possible consequences the development of cardiac remodeling and hypertrophy could have in patients with reduced renal mass or mild renal disease over time. Of relevance, and because of the possible clinical implication, this model may have for kidney donors, we need to emphasize that there is relevant literature regarding safety in this population. Indeed, in a retrospective study, Ibrahim et al. (16) reported that kidney donors' risk of CKD is similar to that of the general population and that quality of life and kidney function were preserved. It should be noted, however, that other studies have reported that renal donation does result in a slight reduction in GFR of ∼20–40%, and the presence of proteinuria has been observed (28). It remains, however, unknown whether such a small reduction in renal function and the increase in proteinuria are associated with cardiac impairments in these otherwise normal individuals. Indeed, to date, detailed examination of the heart in kidney donors has not occurred, and we have no data to understand the myocardial response in the setting of a reduction in renal mass by UNX. Cardiac surveillance studies should be considered in kidney donors to assess the myocardial response to UNX and the possible role of other cardiovascular risks in this population.

In summary, our study indicates that structural, functional, and genetic changes occur in the LV myocardium after UNX. Future studies are necessary to address the precise mechanisms of this kidney-heart connection and possible clinical implications in the setting of mild renal disease and uninephrectomy.

GRANTS

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 HL36634, PO1 HL76611, DK47060, and HL55552

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: F.L.M., P.M.M., A.C., S.J.S., T.I., H.H.C., and J.C.B.J. conception and design of research; F.L.M., B.K.H., E.A.O., and G.E.H. performed experiments; F.L.M. and J.K. analyzed data; F.L.M., P.M.M., S.J.S., J.K., T.I., H.H.C., and J.C.B.J. interpreted results of experiments; F.L.M. prepared figures; F.L.M. and J.C.B.J. drafted manuscript; F.L.M., P.M.M., A.C., S.J.S., T.I., S.M., K.A.N., M.M.R., H.H.C., and J.C.B.J. edited and revised manuscript; F.L.M., A.C., and J.C.B.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Denise M. Heublein and Sharon M. Sandberg for their collaboration.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ando K, Ohtsu H, Arakawa Y, Kubota K, Yamaguchi T, Nagase M, Yamada A, Fujita T. Rationale and design of the Eplerenone combination versus conventional agents to lower blood pressure on urinary antialbuminuric treatment effect (EVALUATE) trial: a double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the antialbuminuric effects of an aldosterone blocker in hypertensive patients with albuminuria. Hypertens Res 33: 616–621, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bianchi S, Bigazzi R, Campese VM. Long-term effects of spironolactone on proteinuria and kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 70: 2116–2123, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biollaz J, Durr J, Brunner HR, Porchet M, Gavras H. Escape from mineralocorticoid excess: the role of angiotensin II. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 54: 1187–1193, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de ZD, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cappola TP, Matkovich SJ, Wang W, van BD, Li M, Wang X, Qu L, Sweitzer NK, Fang JC, Reilly MP, Hakonarson H, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW. Loss-of-function DNA sequence variant in the CLCNKA chloride channel implicates the cardio-renal axis in interindividual heart failure risk variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 2456–2461, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cataliotti A, Malatino LS, Jougasaki M, Zoccali C, Castellino P, Giacone G, Bellanuova I, Tripepi R, Seminara G, Parlongo S, Stancanelli B, Bonanno G, Fatuzzo P, Rapisarda F, Belluardo P, Signorelli SS, Heublein DM, Lainchbury JG, Leskinen HK, Bailey KR, Redfield MM, Burnett JC., Jr Circulating natriuretic peptide concentrations in patients with end-stage renal disease: role of brain natriuretic peptide as a biomarker for ventricular remodeling. Mayo Clin Proc 76: 1111–1119, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cataliotti A, Rodeheffer RJ, Mahoney DW, Lam CSP, Redfield MM, Martin FL, Burnett JC. Burden of chronic renal insufficiency in the general population and added predictive power of GFR to BNP and NT-proBNP in detection of altered ventricular structure and function (Abstract). Circulation 118: S1173, 10282 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costello-Boerrigter LC, Boerrigter G, Harty GJ, Cataliotti A, Redfield MM, Burnett JC., Jr Mineralocorticoid escape by the kidney but not the heart in experimental asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Hypertension 50: 481–488, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dries DL, Exner DV, Domanski MJ, Greenberg B, Stevenson LW. The prognostic implications of renal insufficiency in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 681–689, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edwards NC, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP. Aortic distensibility and arterial-ventricular coupling in early chronic kidney disease: a pattern resembling heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 94: 1038–1043, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edwards NC, Hirth A, Ferro CJ, Townend JN, Steeds RP. Subclinical abnormalities of left ventricular myocardial deformation in early-stage chronic kidney disease: the precursor of uremic cardiomyopathy? J Am Soc Echocardiogr 21: 1293–1298, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Edwards NC, Steeds RP, Stewart PM, Ferro CJ, Townend JN. Effect of spironolactone on left ventricular mass and aortic stiffness in early-stage chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 54: 505–512, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elger M, Bankir L, Kriz W. Morphometric analysis of kidney hypertrophy in rats after chronic potassium depletion. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 262: F656–F667, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Epstein M, Williams GH, Weinberger M, Lewin A, Krause S, Mukherjee R, Patni R, Beckerman B. Selective aldosterone blockade with eplerenone reduces albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 940–951, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fried LF, Shlipak MG, Crump C, Bleyer AJ, Gottdiener JS, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Newman AB. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in elderly individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 1364–1372, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, Gross CR, Matas AJ. Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 360: 459–469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jain M, Jakubowski A, Cui L, Shi J, Su L, Bauer M, Guan J, Lim CC, Naito Y, Thompson JS, Sam F, Ambrose C, Parr M, Crowell T, Lincecum JM, Wang MZ, Hsu YM, Zheng TS, Michaelson JS, Liao R, Burkly LC. A novel role for tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) in the development of cardiac dysfunction and failure. Circulation 119: 2058–2068, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korinek J, Kjaergaard J, Sengupta PP, Yoshifuku S, McMahon EM, Cha SS, Khandheria BK, Belohlavek M. High spatial resolution speckle tracking improves accuracy of 2-dimensional strain measurements: an update on a new method in functional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 20: 165–170, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Korinek J, Wang J, Sengupta PP, Miyazaki C, Kjaergaard J, McMahon E, Abraham TP, Belohlavek M. Two-dimensional strain—a Doppler-independent ultrasound method for quantitation of regional deformation: validation in vitro and in vivo. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 18: 1247–1253, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lam CSP, Roger V, Rodeheffer RJ, Redfield MM. Diverse cardiac geometry and cardiorenal interaction in diastolic heart failure (Abstract). J Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 Suppl. A, 51A 3–24-0007 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levin A. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease prior to dialysis. Semin Dial 16: 101–105, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mayes D, Furuyama S, Kem DC, Nugent CA. A radioimmunoassay for plasma aldosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 30: 682–685, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel PC, Ayers CR, Murphy SA, Peshock R, Khera A, de Lemos JA, Balko JA, Gupta S, Mammen PP, Drazner MH, Markham DW. Association of cystatin C with left ventricular structure and function: the Dallas Heart Study. Circ Heart Fail 2: 98–104, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shirley DG, Walter SJ. Acute and chronic changes in renal function following unilateral nephrectomy. Kidney Int 40: 62–68, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shlipak MG, Wassel Fyr CL, Chertow GM, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Satterfield S, Cummings SR, Newman AB, Fried LF. Cystatin C and mortality risk in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 254–261, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sudoh T, Maekawa K, Kojima M, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Matsuo H. Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA encoding a precursor for human brain natriuretic peptide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 159: 1427–1434, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teekakirikul P, Eminaga S, Toka O, Alcalai R, Wang L, Wakimoto H, Nayor M, Konno T, Gorham JM, Wolf CM, Kim JB, Schmitt JP, Molkentin JD, Norris RA, Tager AM, Hoffman SR, Markwald RR, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Cardiac fibrosis in mice with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is mediated by nonmyocyte proliferation and requires Tgf-beta. J Clin Invest 120: 3520–3529, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wan RK, Spalding E, Winch D, Brown K, Geddes CC. Reduced kidney function in living kidney donors. Kidney Int 71: 1077, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 364: 11–21, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Giacone G, Cataliotti A, Seminara G, Stancanelli B, Malatino LS. Prognostic impact of the indexation of left ventricular mass in patients undergoing dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2768–2774, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Giacone G, Stancanelli B, Cataliotti A, Malatino LS. Left ventricular mass monitoring in the follow-up of dialysis patients: prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy progression. Kidney Int 65: 1492–1498, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Parlongo S, Cutrupi S, Benedetto FA, Cataliotti A, Malatino LS. Norepinephrine and concentric hypertrophy in patients with end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 40: 41–46, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]