Abstract

Context

Few studies have examined the validity of using a single item from the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) for screening for depression.

Objectives

To examine the screening performance of the single-item depression question from the ESAS in chronically ill hospitalized patients.

Methods

A total of 162 chronically ill inpatients age 65 and older completed a survey after admission that included the well-validated, 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) and four single-item screening questions for depression based on the ESAS question, using two different time frames (“now” and “in the past 24 hours”) and two response categories (a 0–10 numeric rating scale [NRS] and a categorical scale: none, mild, moderate and severe).

Results

The GDS-15 categorized 20% (n=33) of participants as possibly being depressed with a score ≥ 6. The NRS for depression “now” achieved the highest level of sensitivity at a cut-off ≥1 (68.8%) and an acceptable level of specificity was obtained at a cut-off of ≥5 (82.2%). For depression “in the past 24 hours,” a cut-off of ≥1 achieved a sensitivity of 68.8% and a cut-off of ≥7 a specificity of 80.3%. For the categorical scale, a cutoff of “none” provided the best level of sensitivity for depression “now” (65.6%) and “in the past 24 hours” (81.3%), with an acceptable level of specificity being obtained at ≥ “mild” (68.8%) and ≥ “moderate” (68.8%), respectively.

Conclusion

These single-item measures were not effective in screening for probable depression in chronically ill patients regardless of the time frame or the response format used but a cut-off of ≥5 or “mild” or greater did achieve sufficient specificity to raise clinical suspicion.

Keywords: Depression, validity, Geriatric Depression Scale, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, chronically ill hospitalized elderly patients

Introduction

Patients referred to palliative care generally have many symptoms.1 Clinicians need rapid and valid approaches to screen for a broad range of symptoms in order to provide quality care and ease suffering. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) is a concise instrument for assessing multiple symptoms that has obtained widespread acceptance in palliative care nationally and internationally for clinical, research, and administrative purposes.2,3 The ESAS consists of an 11-point, self-report numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0 to 10 that is designed to evaluate psychological and physical symptoms such as pain, tiredness, nausea, drowsiness, appetite, well-being, shortness of breath, depression and anxiety.4 The ESAS is designed for repeated quantitative measurements of symptom intensity with minimal patient burden.2

Depression is included in the ESAS because it can diminish a patient’s quality of life and contribute to poorer outcomes. 5 Depression is common in advanced illness and is characterized by at least two weeks of persistent low mood or anhedonia accompanied by sleep disruption; weight loss and change in appetite; psychomotor retardation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness, loss, or guilt; diminished ability to think or concentrate; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation.6 Among chronically ill patients, the prevalence of depression ranges from 1% to 53%.1 Diagnosing depression can be challenging in chronically ill patients and in the palliative care setting as the underlying illness or its treatments may mimic physical symptoms of depression, and a focus on relief of somatic symptoms may often leave depression undiagnosed. Busy clinicians need rapid screening instruments to support clinical efficiency and minimize patient burden.

There are many depression screening instruments available that vary in length (two items7 to 28 items8), administration time (ranging from two minutes to six minutes9), time frame (“today”, “past week,” “past few weeks,” “past month,” and “recently”), and response format (dichotomous or categorical).10 The selection of a particular screening instrument should be based not only on its ability to detect the presence (sensitivity) or absence (specificity) of depression in a particular patient population, but also the feasibility, administration, and scoring time, and ability to monitor change in depression over time.9

We used data from a randomized clinical trial of a palliative medicine intervention in which all patients were screened for depression using a validated instrument to examine the validity of single-item measures for depression based on the question from the ESAS. We hypothesized that single-item measures using a 0–10 NRS or categorical scale (“none,” “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe”) would correlate well with each other and with a valid screening instrument.

Methods

Description of Setting and Participants

Participants were chronically ill inpatients 65 years or older admitted to the medicine or cardiology services of a large academic medical center with a primary diagnosis of cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF), or cirrhosis. All subjects were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of a palliative medicine consultation intervention.11 Participants were required to provide written informed consent and speak English.

Procedure

The data analyzed in this report are from a prospective, randomized clinical trial that compared a proactive palliative medicine consultation with usual hospital care.11 Data collection was undertaken from March 2001 to December 2003. Upon study enrollment, all patients completed a survey that assessed a range of items including demographic information such as date of birth, sex, education level, race, and marital status. A trained research assistant also assessed pain, dyspnea, and anxiety at baseline, recording patients’ responses using a 0–10 NRS. The Committee on Human Research at the University California at San Francisco approved this study (H8695-35172-01).

Screening Patients for Depression

The research assistant also screened each participant for depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15). Each item in the GDS-15 is scored dichotomously (yes/no) and inquires into subjective depression experienced in the past week.12 The GDS-15 ranges from 0– 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Based on previous research, we categorized patients as no depression (0 to 5) or probable depression (6 or more).13 Among our sample of participants, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient revealed that the GDS-15 had an acceptable level of internal consistency (α= 0.79).

The research assistant also administered two single-item assessments to screen for depression, based on the depression question described in the ESAS, which asks respondents to rate the severity of depression on an 11-point NRS ranging from 0 “not depressed” to 10 “worst possible depression.” Each participant was asked to rate their depression “now” and “in the past 24 hours” using two approaches. The first approach used a categorical scale and asked patients, “If you were to use words to describe your worst depression now, would you say it was none, mild, moderate, or severe?” The second approach used an NRS and asked the patient, “On a scale of 0–10, with zero being no depression and 10 being the worst depression you can imagine, how would you rate the worst depression you have now?” Participants were asked to use the same categorical and NRS scales to rate their “worst depression in the past 24 hours.”

Statistical Analysis

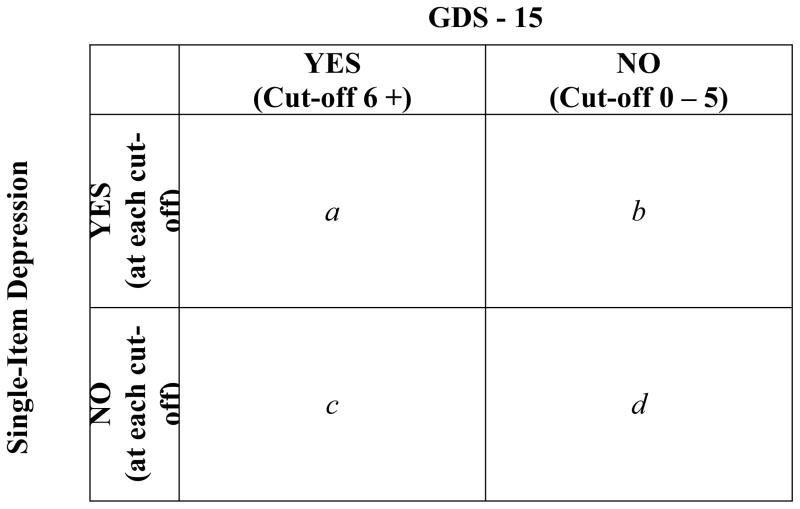

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means [SDs]) were used to examine the distribution of measures. Chi-squared (χ2) analyses were used to test for bivariate associations between depression and personal characteristics. Pearson correlations (r) were used to examine agreement between the various measures of depression. Interpretation of correlations was based on guidelines proposed by Cohen.14 Correlation coefficients were categorized to identify the strength of the relationship between measures as weak (r= 0.1–0.29), moderate (0.30–0.49), and strong (0.50–1.0). Although this interpretation may be considered stringent within the psychological literature,15 we felt this interpretation was appropriate for testing the efficacy of these single-item measures of depression for potential use in a clinical setting. The screening performance of the single-item depression measures was assessed using the GDS-15 as a validated standard. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the single-item NRS and categorical scales were calculated as shown in Fig. 1. We calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve to assist in our interpretation of the usefulness of the single-item measures in screening for depression. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 17; SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL) was used to analyze these data.

Fig. 1.

A 2 × 2 table demonstrating the calculation of sensitivity (a/(a + c)), specificity (d/(b + d)), positive predictive value (a/(a + b)), and negative predictive value (d/(c + d))

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 162 chronically ill hospitalized patients were enrolled in the study. Overall, the mean age of participants was 77 years (SD 7.9; range 65–96 years), most were white (69%, n= 111), and half were men (54%, n= 87). The majority of participants was either divorced/widowed (43%, n= 70) or married/partnered (41%, n= 66) and had completed at least some college (55%, n= 89). Heart failure was the most common primary diagnosis (43%, n= 70), followed by cancer (28%, n= 45), COPD (22%, n= 35), and cirrhosis (4%, n= 7).

Descriptive Characteristics of Depression Items

The GDS-15 categorized 20% (n= 33) of participants as having probable depression (Table 1). With the GDS-15, there were no associations between those subjects that screened positively for probable depression and those that did not by age (F= 0.2, P= 0.7), gender (χ2 = 0.8, P= 0.4), or primary diagnosis (χ2 = 2.3, P= 0.5) using a cutoff of ≥6 or a continuous scale. Using the single-item categorical measure for depression, 15.4% of participants reported having moderate to severe depression. Whereas there was no association between moderate to severe depression and age (P= 0.2) or primary diagnosis (P= 0.4), significantly more women than men (21% vs. 12%, P-0.05) rated themselves as having moderate to severe depression. The depression “in the past 24 hours” categorical scale identified almost 38% of participants with moderate to severe depression with no associations with age (P= 0.2), gender (P= 0.2), or primary diagnosis (P= 0.5). The mean score for the NRS for depression “now” was 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.7, 2.6). Using the NRS, there were no associations between rating and age or gender using depression “now” (age: P= 0.06, gender: P= 0.3) but patients with COPD had significantly higher mean scores (P= 0.007) for depression “now” (mean= 3.4, 95% CI 2.6, 4.2) compared to those with cancer (mean= 1.7, 95% CI 0.9, 2.5) or HF (mean=1.8, 95% CI 1.2, 2.3). The mean score for depression “in the past 24 hours” was 3.8 (95% CI 3.3, 4.4). Increasing age was associated with higher scores (P= 0.02) but gender was not (P= 0.7) and patients with COPD again reported significantly higher (P= 0.01) scores (mean= 5.2, 95% CI 2.4, 3.9) than those with cancer (mean= 3.7, 95% CI 2.6, 4.8), or HF (mean= 3.2, 95% CI 2.4, 3.8). We excluded patients with cirrhosis from the primary diagnosis comparisons because of small numbers (n= 7).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Five Items Used to Assess Depression

| GDS-15 | Depression

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Now | Past 24 hours | ||

| GDS-15 | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 3.6 (3.4, 4.0) | ||

| % (n) | |||

| None (Cut-off: 0 – 5) | 75.3 (122) | ||

| Probable: (Cut-off: 6 – 15) | 20.4 (33) | ||

| Categorical | % (n) | % (n) | |

| None | 52.5 (85) | 35.2 (57) | |

| Mild | 27.8 (45) | 23.5 (38) | |

| Moderate | 14.2 (23) | 25.9 (42) | |

| Severe | 1.2 (2) | 11.7 (19) | |

| Numeric Rating Scale | |||

| Mean (95%CI) | 2.2 (1.7, 2.6) | 3.8 (3.3, 4.4) | |

CI = confidence interval.

Agreement Between the GDS-15 and Single-Item Assessments of Depression

As shown in Table 2, a weak level of agreement was obtained between the GDS-15 and the categorical single-item measures of depression regardless of the time frame (“now”: r= 0.27, or “in the past 24-hours”: r= 0.29). A moderate level of agreement was obtained between the NRS and the GDS-15 for depression “now” (r= 0.37) and “in the past 24 hours” (r= 0.34).

Table 2.

Agreement Between Measures a

| GDS-15 | Depression Now

|

Depression Past 24 Hours

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical | NRS | Categorical | NRS | ||

| Depression Now | |||||

| Categorical | 0.27 | - | - | - | - |

| NRS | 0.37 | 0.83 | - | - | - |

| Depression Past 24 Hours | |||||

| Categorical | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.58 | - | - |

| NRS | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.85 | - |

NRS = numeric rating scale.

Using correlation coefficients.

Correlation Between Categorical and NRS Ratings of Depression

There was a strong correlation between the categorical scale and the NRS for depression “now” (r= 0.83) and depression “in the past 24 hours” (r= 0.85). However, there was only moderate correlation between depression “now” and “in the past 24 hours” using the categorical scale (r= 0.58) or the NRS (r= 0.52).

Sensitivity and Specificity of Single-Item Categorical Measures of Depression

The screening performance for the categorical scale demonstrated that, for depression “now” and “in the past 24 hours,” there was no cut-off demonstrating acceptable levels of both sensitivity and specificity (Table 3). For depression “now,” the highest level of sensitivity was obtained at a cut-off of “none” (65.6%), and an acceptable level of specificity was obtained at ≥ “mild” (85.1%). For depression “in the past 24 hours,” an acceptable level of sensitivity was obtained using a cut-off of “none” (81.3%) and an acceptable level of specificity was obtained at a cut-off of ≥ “moderate” (87.7%). The area under the ROC curve for the categorical measures of depression “now” was 62.3% and “in the past 24 hours” was 62.2%, confirming the poor test characteristics at all cut-offs.

Table 3.

The Screening Characteristics of the Single-Item Categorical Scales of Depression “Now” and “In the Past 24 Hours” When Compared With the GDS-15a (n=154)

| Categorical Scales | Categorized as Depressed | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Depression Now | |||||

| Cut-off: | |||||

| Mild/Moderate/Severe | 70 | 65.6 | 59.5 | 30.0 | 86.7 |

| Moderate/Severe | 25 | 21.9 | 85.1 | 28.0 | 80.4 |

| Severe | 2 | 0.0 | 98.3 | 0 | 78.8 |

| Depression Past 24 Hours | |||||

| Cut-off: | |||||

| Mild/Moderate/Severe | 99 | 81.3 | 40.2 | 26.3 | 89.1 |

| Moderate/Severe | 61 | 56.3 | 64.8 | 29.5 | 84.9 |

| Severe | 19 | 12.5 | 87.7 | 21.1 | 79.3 |

Geriatric Depression Scale-15 is scored from 0–15 where a score from 0–5 indicates no depression and a score of 6 or more indicates a positive screen for depression.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Single-Item NRS Measures of Depression

Screening performance at all potential cut-offs for the NRS for depression “now” and “in the past 24 hours” was similar to the categorical scale when compared to the GDS-15 (Table 4). For both time frames, there was no cut-off where the sensitivity and specificity were both at an acceptable level. For depression “now,” the highest level of sensitivity was obtained at a cut-off of ≥1 (68.8%), and a cut-off of ≥5 provided an acceptable level of specificity (82.8%). Similarly for depression “in the past 24 hours,” an acceptable level of sensitivity was obtained using a cutoff of ≥1 (84.4%) and an acceptable level of specificity was obtained using a cut-off of ≥7 (80.3%). The area under the ROC curve for NRS for depression “now” was 67.1%, and “in the past 24 hours” was 67.4%, confirming that the screening characteristics of these two items are poor.

Table 4.

The Screening Performance of Single-Item Numeric Rating Scales of Depression “Now” and “In the Past 24 Hours” When Compared With the GDS-15 a (n= 154)

| Cut-off for Numeric Rating Scale | Categorized as Depressed | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Depression Now | |||||

| ≥ 1 | 83 | 68.8 | 50.0 | 26.5 | 85.9 |

| ≥ 2 | 69 | 62.5 | 59.8 | 29.0 | 85.9 |

| ≥ 3 | 52 | 59.4 | 73.0 | 36.5 | 87.3 |

| ≥ 4 | 46 | 53.1 | 76.2 | 37.0 | 86.1 |

| ≥ 5 | 35 | 43.8 | 82.8 | 40.0 | 84.9 |

| ≥ 6 | 26 | 34.4 | 87.7 | 42.3 | 83.6 |

| ≥ 7 | 13 | 21.9 | 95.1 | 53.8 | 82.3 |

| ≥ 8 | 10 | 18.8 | 96.7 | 60.0 | 81.9 |

| ≥ 9 | 6 | 12.5 | 98.4 | 66.7 | 81.1 |

| 10 | 3 | 9.4 | 100 | 100 | 80.9 |

| Depression Past 24 Hours | |||||

| Depressed | |||||

| ≥ 1 | 107 | 84.4 | 34.4 | 25.2 | 89.4 |

| ≥ 2 | 101 | 84.4 | 39.3 | 26.7 | 90.5 |

| ≥ 3 | 87 | 78.1 | 49.2 | 28.7 | 89.6 |

| ≥ 4 | 80 | 75.0 | 54.1 | 30.0 | 89.2 |

| ≥ 5 | 70 | 68.8 | 60.7 | 31.4 | 88.1 |

| ≥ 6 | 58 | 59.4 | 68.0 | 32.8 | 86.5 |

| ≥ 7 | 36 | 37.5 | 80.3 | 33.3 | 83.1 |

| ≥ 8 | 31 | 34.3 | 83.6 | 35.5 | 82.9 |

| ≥ 9 | 19 | 15.6 | 88.5 | 26.3 | 80.0 |

| 10 | 13 | 15.6 | 93.4 | 38.5 | 80.9 |

Geriatric Depression Scale-5 is scored from 0–15 where a score from 0–5 indicates no depression and a score of 6 or more indicates a positive screen for depression.

Discussion

We found that the single-item assessments that we used to screen for probable depression among chronically ill, hospitalized elders demonstrated poor test characteristics regardless of the time frame or response format chosen. At no level of response did these single-item measures simultaneously achieve an acceptable level of sensitivity and specificity when compared to the GDS-15, a validated and internationally accepted depression screening tool.16 Furthermore, the area under the ROC curve for each NRS and categorical scale item was poor (46%–53%), indicating that these measures were only as good as chance for screening for the presence of probable depression. Given the poor performance of these single-item measures, they cannot be endorsed as reliable screens for depression, and validated tools that reflect the multidimensional aspects of depression and assess psychological as well as physical manifestations of depression, such as the GDS-15, should be used for screening depression.

The sensitivity and specificity of single-item measures of depression have been previously examined by comparing the single-item measure with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which is a valid and reliable screening tool for depression and anxiety in medically ill patients.17 The authors suggested that using a cut-off of ≥ 2 on the single-item measure provided an acceptable balance between sensitivity (77%) and specificity (55%) for the NRS. 17 We found similar levels of sensitivity and specificity at a cut-off of ≥1 on the NRS or greater than “none” on the categorical scale, consistent with this prior research. The authors in the previous study concluded that, because of a significant number of false negatives, it would be important for clinicians to conduct more in-depth evaluations in any patient who appeared depressed regardless of the result of the single-item screen. Overall, our findings confirm these conclusions. Given the high level of specificity we obtained using a cut-off of “moderate” or “severe” on the categorical scale or > 5 on the NRS, responses in this range should create a high index of suspicion for probable depression. However, as a result of poor sensitivity, these items cannot be relied on for the identification of probable depression.

Two studies have evaluated brief screening or case-finding instruments for depression and found that they could perform well in certain patient populations. In a study of testicular cancer survivors, the single question “Are you depressed?” with answers “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know” achieved an acceptable level of sensitivity (88%) and specificity (84%) compared to the depression subscale of the HADS.18 A two-item depression screening instrument performed similarly among primary care outpatients (sensitivity= 96%, specificity= 66%) using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule as the gold standard.7 Further research could examine the characteristics of these screening approaches among chronically ill and palliative care populations.

Given that depression is defined as the patient having at least two weeks of persistent low mood or anhedonia,6 we expected a high level of agreement between patient responses to depression “now” and “in the past 24 hours.” However, the agreement between the two time frames for the categorical scale (r= 0.58) and the NRS (r= 0.52) was not nearly as strong as the agreement between the two response formats for depression “now” (r= 0.83) or “in the past 24 hours” (r= 0.85). Whereas patients rate depression “now” and in “the past 24 hour” similarly regardless of the scale used, they report variability over a 24-hour time frame in each scale. These findings suggest that although the single-item measures we used are not adequate screens for depression, they are likely assessing some aspect of the patient experience that varies from day to day and does not depend on which type of scale is used to measure it. The fact that a single-item assessment of depression contributes to the overall effectiveness of the ESAS and that a single item correlated well with the HADS in survivors of testicular cancer further supports that this question assesses a meaningful part of patient experience. Future research could examine the meaning of the responses to the single-item measure of depression, how responses change over time, and the factors that contribute to change to determine the utility of this measure as an outcome among chronically ill patients and in the palliative care setting.

Recognizing that single-item, self-report measures may not be adequate for screening a complex psychological issue such as depression in chronically ill patients, alternative approaches may be needed to screen efficiently. With the increasing acceptance and use of mobile technology within the hospital and clinical settings, the more robust multi-item assessments that have demonstrated good validity and reliability may be able to be more easily incorporated into palliative care consultations. Having patients input responses directly into mobile computer technology (laptop computers, personal digital assistants [PDAs], mobile phones, or smartphones) would allow information to be instantly recorded and saved in patient files. Importantly, the clinician could immediately receive summary data that could be used to guide patient care.

The interpretation of our findings should be tempered with the following limitations. Clinical interviews by experienced clinicians are considered the “gold standard” when diagnosing depression.19 In an effort to minimize the burden among our chronically ill, older participants, we chose a well-recognized and well-validated screening instrument to ascertain the validity of screening with single-item measures. The GDS-15 is a particularly appropriate instrument in this patient population because it includes many items that assess psychological symptoms of depression. It is unlikely that the single-item measures would have performed any better using a different gold standard such as clinical interviews. Furthermore, we found similar sensitivity and specificity for the single-item measures as was seen using the HADS, suggesting that choice of standard would be unlikely to change our results. In addition, we did not define depression in the single-item measures and patients may have interpreted the question in many different ways.

Given the importance of diagnosing depression among chronically ill elders in the hospital setting,20 it is incumbent on clinicians to accurately and efficiently screen for and diagnose depression. There are brief single- or two-item screening tools that have been reported to accurately screen for the presence of depression in other patient populations. Use of the item “Are you depressed?” might be a better choice for screening for depression but first needs to be tested in chronically ill and palliative care patients. In using the ESAS, a cut-off of ≥5 should create a high index of suspicion for depression and motivate clinicians to explore the possibility more thoroughly, although lower scores do not rule out depression. The use of validated instruments such as the GDS-15 remains the best approach for screening for depression in chronically ill patients and in the palliative care setting and mechanisms for efficiently administering and scoring such instruments may offer the best approach to screening for depression in these patients. The clinical importance of depression should motivate further research in this area.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded and Dr. Pantilat supported by grant 1-K23-AG01018-01 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. C. Seth Landefeld has received grants from the National Institute on Aging, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation.

We thank all patients and families who participated in this study and the palliative care team members who helped care for them. We also thank Joanne Batt, BA, Wrenn Levenberg, BA, and Emily Philipps, BA, research assistants for the Palliative Care Program at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who contributed to the development of resources and the collection and management of data. We thank Stephen J. McPhee, MD (UCSF) and Bernard Lo, MD (UCSF) for their input on the design of the study.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe S, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C, Mawani A. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System--what do patients think? Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(6):675–683. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: a 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991--2006) Palliat Med. 2008;22(2):111–122. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000 May 1;88(9):2164–2171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert NM, Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, et al. Depression and clinical outcomes in heart failure: an OPTIMIZE-HF analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122(4):366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(7):439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willmott SA, Boardman JA, Henshaw CA, Jones PW. Understanding General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) score and its threshold. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(8):613–617. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulrow CD, Williams JW, Jr, Gerety MB, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(12):913–921. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(10):765–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pantilat SZ, O’Riordan DL, Dibble SL, Landefeld CS. Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;(5):165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiner AS, Hayakawa H, Morimoto T, Kakuma T. Screening for late life depression: cut-off scores for the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia among Japanese subjects. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(6):498–505. doi: 10.1002/gps.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen JW. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemphill JF. Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):78–79. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell AJ, Bird V, Rizzo M, Meader N. Diagnostic validity and added value of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression in primary care: a meta-analysis of GDS(30) and GDS(15) J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vignaroli E, Pace EA, Willey J, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System as a screening tool for depression and anxiety. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):296–303. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skoogh J, Ylitalo N, Larsson Omerov P, et al. ‘A no means no’--measuring depression using a single-item question versus Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(9):1905–1909. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison TE, McCabe MP, Mellor D. An examination of the “gold standard” diagnosis of major depression in aged-care settings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(5):359–367. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318190b901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson CJ, Cho C, Berk AR, Holland J, Roth AJ. Are gold standard depression measures appropriate for use in geriatric cancer patients? A systematic evaluation of self-report depression instruments used with geriatric, cancer, and geriatric cancer samples. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):348–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]