Abstract

Native cowhage spicules, and heat-inactivated spicules containing histamine or capsaicin, evoke similar sensations of itch and nociceptive sensations in humans. In ongoing studies of the peripheral neural mechanisms of chemical itch and pain in the mouse, extracellular electrophysiological recordings were obtained, in vivo, from the cell bodies of mechanosensitive nociceptive neurons in response to spicule stimuli delivered to their cutaneous receptive fields (RFs) on the distal hindlimb. A total of 43 mechanosensitive, cutaneous, nociceptive neurons with axonal conduction velocities in the C-fiber range (C-nociceptors) were classified as CM if responsive to noxious mechanical stimuli, such as pinch, or CMH if responsive to noxious mechanical and heat stimuli (51°C, 5 s). The tips of native cowhage spicules, or heat-inactivated spicules containing histamine or capsaicin, were applied to the RF. Heat-inactivated spicules containing no chemical produced only a transient response occurring during insertion. Of the 43 mechanosensitive nociceptors recorded, 20 of the 25 CMHs responded to capsaicin, and of these, 13 also responded to cowhage and/or histamine. In contrast, none of the 18 CMs responded to any of the chemical stimuli. The time course of the mean discharge rate of CMHs was similar in response to each type of spicule and generally similar, although reaching a peak earlier, to the temporal profiles of itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by the same stimuli in humans. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by these punctuate chemical stimuli are mediated at least in part by the activity of mechanoheat-sensitive C-nociceptors. In contrast, activity in mechanosensitive C-nociceptors that do not respond to heat or to pruritic chemicals is hypothesized as contributing to pain but not to itch.

Keywords: dorsal root ganglion

native cowhage spicules produce a histamine-independent itch that humans perceive as accompanied by lesser sensations of pricking/stinging and burning (Johanek et al. 2008; LaMotte et al. 2009). The spicules, whose active ingredient is a cysteine protease, can be rendered chemically inactive by heating (Reddy et al. 2008). The tips of heat-inactivated spicules are an effective means of delivering a very small amount of different doses of a chemical to superficial nerve terminals in the skin (Reddy et al. 2008; Reddy and Lerner 2010; Sikand et al. 2009, 2011a, 2011b). However, the sensory effects of chemical application by spicule may or may not be similar to the effects of injecting the chemical intradermally. Thus, when injected intradermally, a cysteine protease can elicit little or no reliable sensation of itch (Simone et al. 1987), histamine elicits more itch than nociceptive effects, and capsaicin evokes nociceptive sensations but no itch (Sikand et al. 2011b; Simone et al. 1987). Yet, when each of these same agents is applied to the skin via the tips of one or more heat-inactivated spicules, they each elicit very similar sensory effects: a predominant itch that is accompanied by lesser sensations of pricking/stinging and burning (Reddy et al. 2008; Reddy and Lerner 2010; Sikand et al. 2009, 2011a, 2011b).

C-fiber nociceptors sensitive to mechanical and heat stimuli (CMH nociceptors) respond to native cowhage in monkey and human (Johanek et al. 2008; LaMotte et al. 2009; Namer et al. 2008). Because native cowhage and spicules containing histamine or capsaicin elicit similar qualities and time course of sensations in humans, it was hypothesized that all three types of spicules may activate that same type of nociceptor, namely, the CMHs. On the other hand, capsaicin evokes a weak or no sustained response in CMHs when injected intradermally. In addition, compared with cowhage, histamine appears to elicit a lower incidence of response and fewer action potentials in CMHs when injected intradermally in monkeys (Johanek et al. 2008) or applied by iontophoresis in humans (Handwerker et al. 1991; Namer et al. 2008; Schmelz et al. 1997). There have been no direct comparisons of the effects on CMHs of spicules of native cowhage and spicules of histamine or capsaicin applied in the same way to the skin, nor has there been a systematic study of the responses to chemical stimuli of other mechanosensitive nociceptors that do not respond to heat.

The goal of this study was to compare the action potential responses, in the mouse, of different types of mechanosensitive cutaneous nociceptors to chemical spicules that elicit both itch and nociceptive stimuli in humans. The mouse was chosen as offering several advantages. First, the mouse has been effectively used as a behavioral model of chemically evoked cutaneous itch and pain in humans (LaMotte et al. 2011). Second, transgenic mice are commonly used in behavioral studies of chemical pain and itch and in cellular and molecular genetic in vitro studies of the chemical responses of the cell bodies of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) nociceptive neurons (e.g., Imamachi et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2009), yet there are very few studies of the chemical responses properties of the peripheral terminals of these neurons in vivo. Third, and with regard to the latter point, we have developed a method of visualizing these DRG cell bodies in vivo and recording from them the action potentials generated by stimulation of their cutaneous receptive fields (RFs) (Ma et al. 2010a, 2010b). An added advantage of this approach is that the neurons can be chosen for study based on the size of the soma and by their RF locations and properties in the skin. We thus recorded responses of mechanosensitive cutaneous nociceptive neurons of small diameter to spicules of cowhage, histamine, and capsaicin to determine whether there is a similarity in their responses to each chemical as there is for the itch and nociceptive sensations observed in humans.

METHODS

Animals.

A total of 20 adult male CD1 mice and 5 male C57BL/6 mice, weighing 30–35 g and purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), were used in the study. Mice were housed in groups of four or five under a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. The use and handling of animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine and were in accordance with guidelines provided by National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain.

In vivo electrophysiological recording.

Primary sensory neurons innervating the skin on the hindlimb of mice were recorded using the in vivo physiological preparation previously described (Ma et al. 2010a). Mice were anesthetized with inhalation of 1–2% isoflurane mixed with oxygen via artificial ventilation using a ventilator (MouseVent combined with MouseStat and RightTemp; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). This instrumentation was also used to monitor the SpO2 (maintained over 90%) and to maintain the core temperature of the animal at 37 ± 1°C.

The right L3 or L4 DRG with the corresponding spinal nerve was exposed and isolated following a laminectomy at the levels of L2–L6. The epineurium covering the DRG was removed under a dissection microscope. Oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) was dripped periodically onto the surface of the nerve tissue during the surgery. The ACSF contained (in mM) 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 24 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, and 10 dextrose. The solution was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and had a pH of 7.4 and an osmolarity of 290∼310 mosM. The animal was then fixed to a base plate via two spinal clamps that held the L1 and S1 lumbar vertebrae. The skin was sewn to a ring to hold a pool of warm, oxygenated ACSF. The dorsal root was cut and the DRG lifted onto a small platform that was fixed to the base plate. A vasoconstricting drug, [Arg8]-vasopressin (10 μM in ACSF; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was applied to the spinal nerve to reduce the blood flow, thereby preventing bleeding in the capillary bed of the DRG. The base plate holding the animal was then mounted to a frame under the objective of an upright microscope (BX51WI; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). The neurons on the surface of DRG were viewed through a ×40 water-immersion objective (magnification ×400) using reflective microscopy via an analyzer-50/50 mirror-polarizer set (Ma and LaMotte 2007). The DRG was continuously superfused by oxygenated ACSF at a rate of 3 ml/min, and the temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C via an in-line heater (TC-344A; Warner Instrument, Hamden, CT). Collagenase P (1 mg/ml; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was topically applied to the surface of the DRG for 5 min.

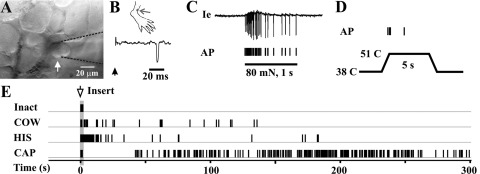

Extracellular recordings from DRG neurons were obtained using a glass micropipette electrode with a tip diameter about the same size as the cell to be recorded (electrode tip fire-polished using Microforge MF-830; Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). The neuronal soma could be drawn into the mouth of the pipette with gentle suction (Fig. 1A), thereby allowing action potentials (APs) to be recorded via an amplifier (Multiclamp 700B; Molecular Device, Sunnyvale, CA). To obtain conduction velocity (CV), APs were evoked by electrically stimulating the RF via a pair of cotton-tipped probes soaked with saline (Fig. 1B). The CV was calculated by dividing the latency of a somal AP by the distance between the electrode and the soma. The criterion for classifying a neuron as having an unmyelinated axon (C-fiber) was a CV of <1.5 m/s (Ma and LaMotte 2007; Ma et al. 2003).

Fig. 1.

Stimulus-evoked action potentials (APs) recorded in vivo from the visualized soma of a C-mechanoheat-sensitive (polymodal) nociceptive neuron. A: bright-field image of the neuron under recording (arrow) with the extracellular electrode (outlined with dashed lines). B: location of cutaneous receptive field (RF; dot) of this neuron on the hairy skin of the hind paw. The conduction velocity (0.72 m/s; trace) was obtained by an electrical stimulus (arrow) applied to the RF. C: responses of this neuron to a von Frey filament with a tip diameter of 200 μm that applied 80 mN of force for 1 s to the RF. The original extracellular recording trace (Ie) is shown with corresponding tic marks for each AP indicated below. D: response to a heat stimulation of 51°C for 5 s from a base of 38°C. E: responses of this neuron to the insertion (arrow and shaded area) of inactive cowage spicules (Inact), native cowhage spicules (COW), and spicules filled with histamine (HIS) or capsaicin (CAP).

Preparation and application of chemically filled spicules.

The chemically filled spicules were prepared using methods previously described for use with human subjects (Sikand et al. 2009). Spicules from the pod of the cowhage plant (M. pruriens, courtesy of M. Ringkamp, Dept. of Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD) were rendered chemically inert by autoclaving them to inactivate the active ingredient, a protease (Reddy et al. 2008). The autoclaved spicules were placed in a solution of either histamine (100 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) prepared in double-distilled water or capsaicin (200 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) in 80% ethanol. After they were observed to fill with the solution, the spicules were dried on filter paper. The tip of a single spicule, held by forceps, was inserted into the superficial skin of the designated RF laterally at an angle of ∼30 deg from the surface of the skin. This method of chemical application has certain advantages over others in that it avoids the mechanical effects of needle insertion and the insertion of fluid into the skin (in the case of hypodermal injection) and avoids the delivery of a vehicle which may itself have bioactive effects. Histamine was prepared in de-ionized water instead of the pH-adjusted salt solution needed for injection; capsaicin was dissolved in alcohol that could then be evaporated. In this way, the capsaicin or histamine remaining in the dried spicules could be applied without the possibly irritating effects of vehicle such as salts and alcohol.

Characterization of RF properties.

The sensory submodality of the distal terminals of the recorded neuron was classified by the static properties of the peripheral RF. Various hand-held stimuli were applied, including stroking with a cotton swab (for innocuous mechanical stimuli), pinching gently with the experimenter's fingers, or indenting with a glass probe or a von Frey filament having a fixed diameter of 200 μM, but differing in bending force (for noxious mechanical stimuli) and by application of heat via a temperature-controlled chip-resister heating probe or cold via ice (for noxious thermal stimuli) (Ma and LaMotte 2007; Ma et al. 2003).

Only mechanosensitive nociceptors with C-fibers were included in this study. Neurons were classified as C-fiber mechanosensitive nociceptors (CMs) if responsive to noxious mechanical stimuli or C-mechanoheat-sensitive nociceptors (CMHs) if responsive to not only mechanical but also heat noxious stimuli (51°C, 5 s). Mechanically insensitive afferents, typically identified using electrical and thermal cutaneous stimuli (Schmelz et al. 2003), were not examined in the present study. Next, the tips of successive groups of three to five inactive spicules were inserted into the RF. The first group consisted of heat-inactivated cowhage spicules. These never evoked a response lasting beyond the moment of insertion. After 5 min, these spicules were removed, three to five native cowhage spicules were applied, and responses were recorded for at least 5 min or longer until discharges ceased (for 1 min). These spicules were removed, and subsequent groups, first of histamine spicules and lastly capsaicin spicules, were applied and recordings made as described.

RESULTS

Functional identification of cutaneous mechanosensitive neurons.

A total of 43 mechanosensitive cutaneous neurons with axonal conduction velocities in the C-fiber range and responsive to nociceptive mechanical and/or thermal stimulation were found with RFs on the hairy skin of the hindlimb. These included 18 CM and 25 CMH neurons. There was no significant difference in the mean CV of CMH and CM neurons (0.46 ± 0.02 vs. 0.48 ± 0.06 m/s, respectively). Most neurons had RFs on the hairy skin of the dorsum of the foot, ankle, or calf. Five CMs and 7 CMHs had RFs on the glabrous skin of the toes, sole, or heal of the foot. We observed no obvious differences in the functional properties of nociceptors according to skin type or location of RF on the hindlimb.

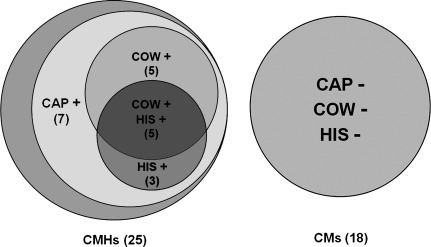

The functional characterization and responses to chemical stimuli of a CMH neuron are illustrated in Fig. 1. None of the CM neurons responded to any of the chemical stimuli, whereas 20 of the 25 CMH neurons responded to capsaicin, and subsets of these responded additionally to cowhage and/or to histamine (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Diagram showing the number of C-nociceptive neurons responsive to native cowhage and to heat-inactivated spicules containing histamine or capsaicin. Each circle represents a group of mechanosensitive C-nociceptive neurons that responded (+) or did not respond (−) to each type of spicule. The chemically responsive neurons were a subset of the 25 C-mechanoheat-sensitive nociceptors (CMHs) tested (the unlabeled gray crescent represents the 5 CMHs that did not respond to the chemical stimuli). None of the 18 C-mechanosensitive nociceptors that were unresponsive to heat (CMs) responded to any of the chemical stimuli.

Responses of cutaneous C-polymodal sensory neurons to punctate chemical stimuli.

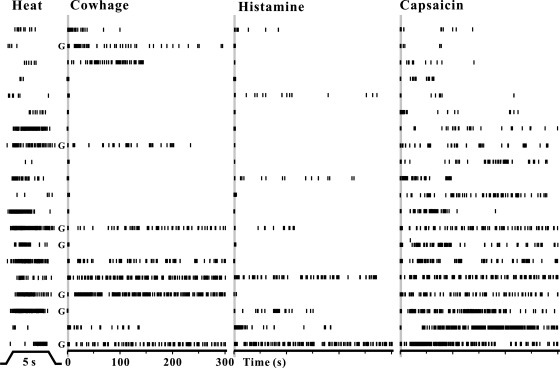

Five of the 25 CMHs were unresponsive to any of the chemical stimuli. The remaining 20 each responded to capsaicin. Of these, five additionally responded to both cowhage and to histamine, seven to neither of these, three to histamine but not cowhage, and five to cowhage but not histamine (Fig. 3). The discharges in Fig. 3 are arranged according to the number of APs evoked by capsaicin from the least at top and the most at bottom. The duration of action potential discharges evoked by the chemically filled spicules varied from 1 to 10 min (the cutoff duration of recording). With only one exception, all neurons (with ongoing activity) stopped discharging as soon as the spicules were removed. Thus there are subpopulations of C-mechanosensitive nociceptors responsive to heat and to capsaicin that differ according to whether they respond to histamine or to cowhage.

Fig. 3.

Temporal patterns of APs evoked by heat, cowhage, histamine, and capsaicin in chemically responsive CMH neurons. Left to right: AP discharges evoked by heat (51°C, 5 s from a base of 38°C, as indicated at bottom), native cowhage spicules, histamine-filled spicules, and capsaicin-filled spicules. Each vertical tic mark indicates the time of occurrence of an AP, and each row represents the recording from a single neuron, sorted according to the number of APs evoked by capsaicin (ascending from top to bottom). Shaded area marks the insertion of spicules. G, neurons with RFs on the glabrous skin.

The numbers of APs evoked by capsaicin-filled spicules were significantly correlated with those evoked by histamine (R = 0.839, P = 0.009) but not with those elicited by native cowhage spicules (R = 0.422, P = 0.224) or by the heat stimulus of 51°C (R = 0.106, P = 0.655). No significant correlation was found between the number of APs evoked by histamine and by cowhage (R = 0.793, P = 0.110) as similarly found for CMHs in the monkey, where histamine was applied by intradermal injection (Johanek et al. 2008).

Unlike CMHs in the monkey, those in the mouse could not be categorized as quickly vs. slowly adapting in their responses to a noxious heat stimulus. There was no link between the discharges evoked by heat and by cowhage for CMHs in the mouse (Fig. 3) as there was for CMHs in the monkey.

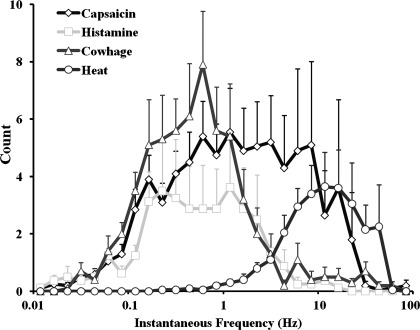

As indicated by the pattern of APs evoked by each stimulus (Fig. 3), the responses of CMHs to each type of spicule were more irregular than they were to heat. The distributions of instantaneous frequencies were averaged for the responses of each CMH to each stimulus (Fig. 4). In relation to the distribution for responses to heat, which exhibits a unimodal peak at about 10 Hz, the distributions for responses to each chemical have multiple peaks at lower frequencies. Capsaicin induced more higher frequency discharges (over 10 Hz), whereas histamine induced almost no discharges over 10 Hz, and cowhage elicited a response that was in between, i.e., with a few minor peaks over 10 Hz.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of the instantaneous frequencies averaged across all neurons responsive to heat or to each chemical stimulus.

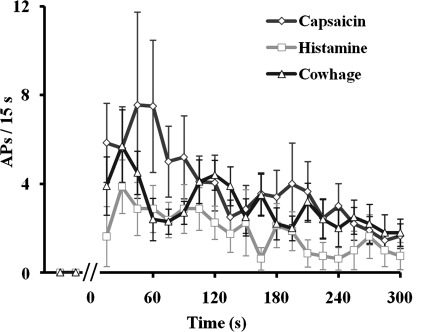

There was a similar time course in the frequencies of discharge evoked by each chemical stimulus (Fig. 5). The responses to each chemical peaked within the first minute after spicule insertion. Although capsaicin appears to have evoked more APs during the first minute, neither the total number of APs nor the number of APs within any of the 15-s time bins were significantly different among the three chemical stimuli (P > 0.05, 1-way ANOVA). This conclusion remained true if only the five neurons that responded to all three chemicals were included (P > 0.05 for time or chemical, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA).

Fig. 5.

Time course of the mean discharge rate evoked in CMH nociceptors in response to native cowhage, histamine-filled, or capsaicin-filled spicules. Neuronal responses are means ± SE of the number of APs within 15-s time bins.

The temporal pattern of responses to each chemical was irregular and characterized by clumps or “bursts” of APs, similar to the responses of CMHs in the monkey to the application of cowhage spicules or to an injection of histamine (Johanek et al. 2008). Using the analysis described in that study, we determined whether such a burstlike pattern differed for the responses of CMHs to each chemical delivered by spicule in the mouse. Briefly, for any two successive interspike intervals, t1 and t2, the onset of a burst was defined by t1/t2 ≥ 5. For each burst detected, t1 represented the interburst interval and 1/t2 indicated the intraburst frequency. The results are summarized in Table 1. Responses evoked by histamine-filled spicules and native cowhage were similar to those previously reported in the monkey (Johanek et al. 2008). Although capsaicin-filled spicules seemed to evoke more APs and more high-frequency bursts than histamine and cowhage, the results were not significantly different due to response variability. In particular, for capsaicin, two outliers (180.4 and 262.5 Hz) contributed to the high value of the mean for 1/t2. When these two data points were excluded, the mean 1/t2 for capsaicin decreased to 3.5 ± 1.2 Hz and was comparable to the mean values of 1/t2 obtained for histamine and cowhage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of bursting in responses evoked by native cowhage, histamine-filled, or capsaicin-filled spicules

| Capsaicin | Histamine | Cowhage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 20 | 8 | 10* |

| Total response, APs/5 min | 77.5 ± 19.8 | 36.9 ± 13.9 | 60.0 ± 10.1 |

| Number of bursts | 9.1 ± 2.3 | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 6.1 ± 1.4 |

| Average intraburst frequency (1/t2), Hz | 25.4 ± 15.3 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 1.4 |

| Average interburst interval (t1), s | 16.8 ± 4.2 | 18.2 ± 3.9 | 11.8 ± 2.5 |

Values are means ± SE; n = no. of neurons.

Only 9 of the 10 cowhage-responsive neurons were included in the bursting analyses. APs, action potentials.

DISCUSSION

The mouse has proven particularly useful in cellular and molecular genetic studies of inflammation and acute pain and itch. The mouse is capable of detecting chemical stimuli delivered by spicule (Akiyama et al. 2010) or by intradermal injection and responds differentially to those chemicals that humans describe as primarily itchy vs. painful (Akiyama et al. 2010; Shimada and LaMotte 2008). Chemical delivery by spicule offers the advantage of applying a minute amount of chemical to a punctate region of skin with negligible mechanical injury. The sensory effects of chemical application by spicule are dependent on the concentration but not appreciably changed by the number of spicules inserted (e.g., 1 vs. 30) within a localized region on the skin (Sikand et al. 2009, 2011b). Similarly, single and multiple spicules of cowhage are equally effective in eliciting responses in a CMH cutaneous nerve fiber in the monkey (Johanek et al. 2008). However, whereas chemical delivery by spicule has proven useful for studies of itch and pain in humans, little is known of the chemical response properties of primary sensory neurons in the mouse.

Rather, the chemical response properties of primary sensory neurons in the mouse, typically those of small diameter that are thought to be nociceptive, have been studied using the acutely dissociated and cultured neuronal cell body as an in vitro model of the responses of its peripheral terminal. The drawbacks of this approach are not only the possible differences in the molecular properties of the cell body and terminals of an intact neuron (Zimmermann et al. 2009) but also the effects of dissociation and culture, such as axotomy and elimination of satellite glia, which result in neuronal hyperexcitability and alterations in chemical signaling pathways (Ma and LaMotte 2005; Zheng et al. 2007).

As in the in vitro approach, the present protocol identified DRG neurons initially on the basis of the small diameters of their cell bodies, visualized in vivo (Ma et al. 2010a). Only neurons with peripheral C-fibers and mechanosensitive cutaneous nociceptors were accepted for study, and of these, we found two types: one responsive to noxious heat (CMHs) and other not (CMs). The response to heat (but not to cold) was singularly predictive as to whether or not the neuron would respond to chemical stimuli. Most CMHs and none of the CMs responded to capsaicin spicules, and subsets of capsaicin-responsive CMHs responded to spicules of histamine and/or cowhage. Thus there are pruriceptive nociceptors that respond to “pruritic” chemicals that evoke itch and nociceptive sensations in humans, and there are “nociceptive specific” nociceptors that respond specifically to noxious mechanical stimuli but do not respond to pruritic chemicals.

The existence of two populations of mechanosensitive nociceptors, one pruriceptive and the other nociceptive specific, may be important for the central neural decoding of itch. One can speculate that if both populations were activated, for example, by pinching the skin, a nociceptive sensation would occur and the central transmission of pruriceptive information would be masked, whereas if CMHs alone were activated by a pruritic chemical, itch could occur. For such a hypothesis to receive further support, similar evidence would be necessary for the existence of nociceptors that are not pruriceptive but rather respond specifically to stimuli that evoke thermal or chemical pain but not itch, such as noxious heat or an intradermal injection of capsaicin (Sikand et al. 2011b). Some initial support for this is found in certain mechanoinsensitive C-fibers in humans that respond to noxious heat or to the injection of capsaicin but are unresponsive to the iontophoresis of histamine (Schmelz et al. 2003).

Because we found that the response to histamine (total number of impulses evoked) was correlated with the response to capsaicin, the former might be mediated via the TRPV1 capsaicin receptor, consistent with results from published in vitro and behavioral studies (Shim et al. 2007). Also, because capsaicin was always presented after histamine in this study, it is conceivable, based on in vitro findings (Kajihara et al. 2010), that some residual histamine might have potentiated the responses of CMHs to the subsequent presentation of capsaicin.

In contrast, the response to cowhage may occur via a different transduction and signaling mechanism, because it was not correlated with responses to histamine or to capsaicin. Similarly, in the monkey, most CMHs responded to cowhage and also to an injection of histamine. Again, the responses were not correlated, suggesting independent mechanisms of activation (Johanek et al. 2008). In addition, there was a subpopulation of cowhage-responsive neurons that did not respond to histamine (31% in the monkey when histamine was injected intradermally and 50% in the present study of the mouse when histamine was applied by spicules). Thus CMH neurons responsive to cowhage and/or to capsaicin spicules but not to histamine may be part of a neural pathway that mediates “histamine-independent” itch and nociceptive sensations elicited by certain pruritic stimuli. These neurons might feed into two types of pruriceptive, nociceptive neuronal pathways in the central nervous system, one responsive to histamine and the other responsive to pruritic chemicals that do not involve histamine, such as cowhage (Davidson et al. 2007; see also Akiyama et al. 2009a, 2009b). Our data do not provide a way to determine whether the activity in a pruriceptive CMH nociceptor might be contributing to the sensation of itch, the sensations of pricking/stinging and/or burning that commonly accompany the itch (Sikand et al. 2009), or some combination of more than one quality of sensation.

The cellular mechanisms by which chemical stimuli from spicules generate action potentials in CMHs are unknown. Histamine activates H1 and H4 receptors (de Esch et al. 2005), and the cysteine protease in cowhage activates protease-activated receptors 2 and 4 (Reddy et al. 2008) or may generate products such as a hexapeptide that activates the MrgprC11 receptors (Liu et al. 2011). These are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that typically signal via Gq proteins to phospholipase C activation and various intracellular signaling pathways. However, the ion channels that serve as effector molecules for generating APs in response to GPCR activation have yet to be identified specifically in pruriceptive nociceptors innervating the skin. Equally important is the lack of specific evidence as to whether these receptors and their signaling pathways are contained within the CMH neuron itself or occur instead, or in addition, in other neurons or even nonneuronal cells. For example, keratinocytes contain TRPV1 receptors (Stander et al. 2004), protease-activated receptors (Steinhoff et al. 1999), and histamine receptors (Yamaura et al. 2009) that when activated may lead to the release of chemicals (Dussor et al. 2009) that activate or modulate the responses of CMH and other sensory neurons. In support of a possible role of other cell types, the cell bodies of CMH neurons are not immunopositive for TRPV1 (Lawson et al. 2008). On the other hand, some CMHs are immunopositive for TRPV1 after an inflammation of the skin (Koerber et al. 2010). CMHs are certainly affected by capsaicin, since they are readily desensitized when the chemical, but not its vehicle, is injected into their cutaneous RFs (Baumann et al. 1991; Johanek et al. 2008). Thus it is conceivable that the expression of TRPV1, while weak and perhaps too low for a positive immunoreactivity in the cell body, is normally sufficiently expressed in the peripheral terminals of CMHs to mediate responses to capsaicin and histamine delivered by spicules.

When the concentrations of each chemical are appropriately chosen, a single spicule containing capsaicin or histamine evokes in humans itch and nociceptive sensations that are the same as those elicited by a single spicule of cowhage (Sikand et al. 2009, 2011b). The sensations are much the same whether it is a group of spicules containing the same chemical applied to a localized region of skin or just a single spicule (Sikand et al. 2011b). In the present study, CMHs responded in similar fashion to each of these three types of spicules applied to their cutaneous RFs. Thus chemical stimuli that elicit similar itch and nociceptive sensations in humans evoke similar discharge rates in CMH nociceptors in the mouse.

The time course and magnitude of CMH responses in the mouse to cowhage were roughly equivalent to those of CMH nerve fibers recorded in the monkey (Johanek et al. 2008) but appear to decline a little more rapidly than the sensory ratings of itch and nociceptive sensations of humans. The magnitude ratings of itch decline to one-half their peak values in 4–6 min after each type of spicule application (Sikand et al. 2009), whereas corresponding mean discharge rates of CMHs in mouse decline to one-half their peak values within 2–3 min. Although there are numerous possibilities for this slight mismatch, including differences due to species or in the types of sensation mediated by these CMH responses, there is the possibility for a role of one or more other types of sensory neurons. For example, in the monkey, there are mechanosensitive nociceptors with A-fibers whose mean discharge rate in response to cowhage, compared with that of CMHs, is slightly delayed in onset, peaks by the second minute, and declines more slowly (Ringkamp et al. 2011). Although the possible responses of these A-fibers to spicules of capsaicin or histamine have yet to be tested in monkey or mouse, a pilot study indicated that CMH nociceptors in monkey do respond to each chemical delivered by spicule, and with a time course not unlike that of mouse CMHs, particularly for those nociceptors with quickly adapting responses to noxious heat (Ringkamp et al. 2010).

In summary, a major finding of the present study is that mechanosensitive nociceptors with C-fibers that respond to punctate pruritic stimulation with cowhage, histamine, or capsaicin are confined to those that also respond to noxious heat. The comparable activation of such “pruriceptive” nociceptors by these punctuate chemical stimuli may help to explain the similarity in the itch and nociceptive sensations elicited by each chemical when applied in the same way to humans (Sikand et al. 2009). In contrast, the mechanosensitive C-nociceptors that respond only to noxious mechanical stimuli but not to pruritic chemicals may constitute a class of “nociceptive specific” nociceptors, the activation of which may elicit pain but not itch.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants NS014624 (to R. H. LaMotte) and NS065091 (to C. Ma) and a Research Startup Grant (to C. Ma) from the Department of Anesthesiology, Yale University School of Medicine. H. Nie was supported by grants from the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (No. 30400596), and the 211 Project of Jinan University, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (21611606, 21610703), Guangzhou 510632, P.R. China.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.M. and R.H.L. conception and design of research; C.M., H.N., and Q.G. performed experiments; C.M. analyzed data; C.M. and R.H.L. interpreted results of experiments; C.M. prepared figures; C.M. and R.H.L. drafted manuscript; C.M., P.S., and R.H.L. edited and revised manuscript; C.M., H.N., Q.G., P.S., and R.H.L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of H. Nie: Guangdong Province Key Laboratory of Pharmacodynamic Constituents of Traditional Chinese Medicine and New Drug Research, College of Pharmacy, Jinan University, Guangzhou, People's Republic of China.

Present address of Q. Gu: Department of General Surgery, Yueyang Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, People's Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- Akiyama T, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Differential itch- and pain-related behavioral responses and micro-opoid modulation in mice. Acta Derm Venereol 90: 575–581, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Excitation of mouse superficial dorsal horn neurons by histamine and/or PAR-2 agonist: potential role in itch. J Neurophysiol 102: 2176–2183, 2009a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Merrill AW, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Activation of superficial dorsal horn neurons in the mouse by a PAR-2 agonist and 5-HT: potential role in itch. J Neurosci 29: 6691–6699, 2009b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann TK, Simone DA, Shain CN, LaMotte RH. Neurogenic hyperalgesia: the search for the primary cutaneous afferent fibers that contribute to capsaicin-induced pain and hyperalgesia. J Neurophysiol 66: 212–227, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, Khasabov SG, Simone DA, Giesler GJ., Jr The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci 27: 10007–10014, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Esch IJ, Thurmond RL, Jongejan A, Leurs R. The histamine H4 receptor as a new therapeutic target for inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26: 462–469, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussor G, Koerber HR, Oaklander AL, Rice FL, Molliver DC. Nucleotide signaling and cutaneous mechanisms of pain transduction. Brain Res Rev 60: 24–35, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker HO, Forster C, Kirchhoff C. Discharge patterns of human C-fibers induced by itching and burning stimuli. J Neurophysiol 66: 307–315, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamachi N, Park GH, Lee H, Anderson DJ, Simon MI, Basbaum AI, Han SK. TRPV1-expressing primary afferents generate behavioral responses to pruritogens via multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11330–11335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanek LM, Meyer RA, Friedman RM, Greenquist KW, Shim B, Borzan J, Hartke T, LaMotte RH, Ringkamp M. A role for polymodal C-fiber afferents in nonhistaminergic itch. J Neurosci 28: 7659–7669, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajihara Y, Murakami M, Imagawa T, Otsuguro K, Ito S, Ohta T. Histamine potentiates acid-induced responses mediating transient receptor potential V1 in mouse primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience 166: 292–304, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber HR, McIlwrath SL, Lawson JJ, Malin SA, Anderson CE, Jankowski MP, Davis BM. Cutaneous C-polymodal fibers lacking TRPV1 are sensitized to heat following inflammation, but fail to drive heat hyperalgesia in the absence of TPV1 containing C-heat fibers. Mol Pain 6: 58, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte RH, Shimada SG, Green BG, Zelterman D. Pruritic and nociceptive sensations and dysesthesias from a spicule of cowhage. J Neurophysiol 101: 1430–1443, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte RH, Shimada SG, Sikand P. Mouse models of acute, chemical itch and pain in humans. Exp Dermatol 20: 778–782, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JJ, McIlwrath SL, Woodbury CJ, Davis BM, Koerber HR. TRPV1 unlike TRPV2 is restricted to a subset of mechanically insensitive cutaneous nociceptors responding to heat. J Pain 9: 298–308, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Tang Z, Surdenikova L, Kim S, Patel KN, Kim A, Ru F, Guan Y, Weng HJ, Geng Y, Undem BJ, Kollarik M, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ, Dong X. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell 139: 1353–1365, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Weng HJ, Patel KN, Tang Z, Bai H, Steinhoff M, Dong X. The distinct roles of two GPCRs, MrgprC11 and PAR2, in itch and hyperalgesia. Sci Signal 4: ra45, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Donnelly DF, LaMotte RH. In-vivo visualization and functional characterization of primary somatic neurons. J Neurosci Methods 191: 60–65, 2010a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, LaMotte RH. Enhanced excitability of dissociated primary sensory neurons after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion in the rat. Pain 113: 106–112, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, LaMotte RH. Multiple sites for generation of ectopic spontaneous activity in neurons of the chronically compressed dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci 27: 14059–14068, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Shimada SG, LaMotte RH. In-vivo responses of cutaneous C-mechanosensitive neurons, and behavior, evoked in the mouse by punctuate chemical stimuli that elicit itch and nociceptive sensations in humans. Soc Neurosci Abstr 5844, 2010b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Shu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Y, Yao H, Greenquist KW, White FA, LaMotte RH. Similar electrophysiological changes in axotomized and neighboring intact dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol 89: 1588–1602, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namer B, Carr R, Johanek LM, Schmelz M, Handwerker HO, Ringkamp M. Separate peripheral pathways for pruritus in man. J Neurophysiol 100: 2062–2069, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VB, Iuga AO, Shimada SG, LaMotte RH, Lerner EA. Cowhage-evoked itch is mediated by a novel cysteine protease: a ligand of protease-activated receptors. J Neurosci 28: 4331–4335, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VB, Lerner EA. Plant cysteine proteases that evoke itch activate protease-activated receptors. Br J Dermatol 163: 532–535, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringkamp M, Borzan J, Schaefer K, Hartke TV, Meyer RA. Activation of polymodal nociceptors in monkey by punctate chemical stimulation with histamine and capsaicin. Soc Neurosci Abstr 5846, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Ringkamp M, Schepers RJ, Shimada SG, Johanek LM, Hartke TV, Borzan J, Shim B, LaMotte RH, Meyer RA. A role for nociceptive, myelinated nerve fibers in itch sensation. J Neurosci 31: 14841–14849, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M, Schmidt R, Bickel A, Handwerker HO, Torebjork HE. Specific C-receptors for itch in human skin. J Neurosci 17: 8003–8008, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M, Schmidt R, Weidner C, Hilliges M, Torebjork HE, Handwerker HO. Chemical response pattern of different classes of C-nociceptors to pruritogens and algogens. J Neurophysiol 89: 2441–2448, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim WS, Tak MH, Lee MH, Kim M, Koo JY, Lee CH, Oh U. TRPV1 mediates histamine-induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12-lipoxygenase. J Neurosci 27: 2331–2337, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada SG, LaMotte RH. Behavioral differentiation between itch and pain in mouse. Pain 139: 681–687, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikand P, Dong X, LaMotte RH. BAM8–22 peptide produces itch and nociceptive sensations in humans independent of histamine release. J Neurosci 31: 7563–7567, 2011a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, LaMotte RH. Sensory responses to injection and punctate application of capsaicin and histamine to the skin. Pain 152: 2485–2494, 2011b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, LaMotte RH. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain 144: 66–75, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone DA, Ngeow JY, Whitehouse J, Becerra-Cabal L, Putterman GJ, LaMotte RH. The magnitude and duration of itch produced by intracutaneous injections of histamine. Somatosens Res 5: 81–92, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stander S, Moormann C, Schumacher M, Buddenkotte J, Artuc M, Shpacovitch V, Brzoska T, Lippert U, Henz BM, Luger TA, Metze D, Steinhoff M. Expression of vanilloid receptor subtype 1 in cutaneous sensory nerve fibers, mast cells, and epithelial cells of appendage structures. Exp Dermatol 13: 129–139, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M, Corvera CU, Thoma MS, Kong W, McAlpine BE, Caughey GH, Ansel JC, Bunnett NW. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 in human skin: tissue distribution and activation of keratinocytes by mast cell tryptase. Exp Dermatol 8: 282–294, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaura K, Oda M, Suwa E, Suzuki M, Sato H, Ueno K. Expression of histamine H4 receptor in human epidermal tissues and attenuation of experimental pruritus using H4 receptor antagonist. J Toxicol Sci 34: 427–431, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JH, Walters ET, Song XJ. Dissociation of dorsal root ganglion neurons induces hyperexcitability that is maintained by increased responsiveness to cAMP and cGMP. J Neurophysiol 97: 15–25, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann K, Hein A, Hager U, Kaczmarek JS, Turnquist BP, Clapham DE, Reeh PW. Phenotyping sensory nerve endings in vitro in the mouse. Nat Protoc 4: 174–196, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]