Abstract

Objectives. We investigated the associations between smoking and friend selection in the social networks of US adolescents.

Methods. We used a stochastic actor-based model to simultaneously test the effects of friendship networks on smoking and several ways that smoking can affect the friend selection process. Data are from 509 US high school students in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 1994–1996 (46.6% female, mean age at outset = 15.4 years).

Results. Over time, adolescents’ smoking became more similar to their friends. Smoking also affected who adolescents selected as friends; adolescents were more likely to select friends whose smoking level was similar to their own, and smoking enhanced popularity such that smokers were more likely to be named as friends than were nonsmokers, after controlling for other friend selection processes.

Conclusions. Both friend selection and peer influence are associated with smoking frequency. Interventions to reduce adolescent smoking would benefit by focusing on selection and influence mechanisms.

Adolescent smoking has declined over the past 2 decades1 yet remains a significant determinant of current and future health outcomes.2 Given the importance of peers during adolescence, it is unsurprising that numerous studies have documented a strong association between friendships and smoking.3–7 The processes linking smoking and friendships, however, are quite complex,8 and several questions remain about the nature of this association. Of particular interest is the lingering issue of endogeneity: how much peer networks affect smoking behavior versus how much smoking affects friendship choices.9–11 Addressing endogeneity is essential to prevention and cessation efforts, as distinct causal processes behind selection and influence imply different policy and intervention prescriptions to combat the negative effects of smoking and other risky health behaviors.

We have focused on explaining 2 empirical patterns: why friends have similar smoking behavior and why popular students are sometimes more likely to smoke than are less popular students. We tested whether similarity in smoking among friends is owing to peer influence or to selecting similar peers as friends. We also tested whether popularity leads to smoking or whether smoking increases students’ popularity.

We used longitudinal data and a recently developed statistical model to simultaneously model the effect of the friendship network on smoking and the effect of smoking on friend selection.12,13 Rather than creating a summary of each individual's network position (e.g., centrality), in this approach we incorporated the complete friendship network. In particular, the model predicted changes in the friendship network (because of smoking and other factors) and adolescents’ smoking behavior (because of friendship network factors). This model has been applied successfully to smoking among European adolescents5,6,13–15 and other health outcomes, such as depression.16–18 To date, however, to our knowledge these methods have not been used to examine smoking among US adolescents.

SMOKING AND FRIEND SELECTION

Adopting a social network perspective that emphasizes the role of peers has greatly benefitted our understanding of many health outcomes,19 including adolescent smoking.8,20,21 It has long been known that friends exhibit similar smoking behavior.22–24 Two processes have been proposed to explain this pattern: peer influence and friend selection. With peer influence, adolescents’ behaviors come to resemble those of their friends over time. Research on peer influence has consistently documented that adolescents are affected by their peers’ tobacco use.4,25–28 Tobacco use within one's network—including best friends, all friends, and friends of friends—is positively associated with one's own use.29 However, peer influence is only part of the link between smoking and peers; one must also consider how smoking affects friendship choices.9,11 Similar adolescents may disproportionately choose each other as friends rather than dissimilar peers. Such homophilous relationships are oftentimes preferred because they are easier to develop and maintain.30 In the case of smoking, similar friends may reinforce each other's smoking behavior or simply provide access to cigarettes.

Smoking may also be associated with friendships through popularity. Research has found that more popular adolescents have an increased susceptibility to smoking.8,11,20,31 The association between popularity and smoking may be related to 2 different processes. One explanation posits that smoking increases adolescents’ attractiveness as friends regardless of one's own smoking behavior.32 That is, smoking may be a path to higher social status. This is supported by evidence that smoking is associated with popularity and instability in popularity over time.31 The other explanation says that popular students are more likely to begin smoking, especially in schools where smoking is perceived to be normative.11 Popular students are more likely to engage in new behaviors as long as they fall within culturally acceptable bounds.20 Both explanations suggest a positive association between smoking and popularity, with popularity increasing smoking behavior and smoking enhancing popularity.

Still, other research has found that students who are socially isolated3 or at either extreme in the school status hierarchy are more likely to smoke.33,34 This implies a nonlinear association between popularity and smoking. Students with either low or high popularity may be more likely to smoke than are students with average popularity. It is also possible that smoking has a curvilinear effect on popularity, with intermediate levels of smoking leading to more or less popularity than does smoking at either extreme. This possibility has rarely been examined in studies that focus on smoking as the outcome.

THE STOCHASTIC ACTOR-BASED MODEL

Our research simultaneously tests the following relations between adolescent friendship networks and smoking: (1) Do friends influence each other's smoking? (2) Do adolescents select friends with similar levels of smoking? (3) Does popularity increase adolescents’ smoking, and is this effect curvilinear? (4) Does smoking increase adolescents’ popularity, and is this effect curvilinear?

To address these questions we conducted a longitudinal network analysis using a stochastic actor-based (SAB) model (also known as a “SIENA” model).12,35 The SAB model was developed to overcome concerns regarding bias in prior research testing peer influence without controlling for selection into friendships.13 The issue is that observed associations between smoking and friendship can be produced through either friend selection or peer influence, thereby necessitating controls for friend selection when estimating peer influence on behaviors such as smoking.10,36 However, commonly used statistical approaches such as cross-lagged regression models do not adequately account for friend selection.13 The SAB model more closely approximates friend selection by estimating how smoking and several other network processes jointly predict which friendships exist and how they change over time.

Even with longitudinal network data, establishing causal effects, such as peer influence, through observational studies is difficult.37 Recent research employing generalized estimating equations with lagged controls for friends’ behavior38 has been criticized, in part, for not adequately addressing the issue of endogenous friend selection.39 The SAB framework allows the simultaneous modeling of friend selection and behavioral assimilation and decomposing autocorrelation in behavior among friends into separate components attributable to network change versus behavioral adaptation. Although the SAB framework is an improvement over the generalized estimating equation approach, drawing causal inferences requires additional assumptions. The first is that the peer selection and behavior change models are properly specified. That is, there are no unobserved factors that drive change in both networks and behavior conditional on the initial constellation of behavior and social ties. The second assumption, temporal separability, is that the total observed change in behavior and network ties can be broken down into a series of smaller, unobserved changes. Under these assumptions it is possible to establish Granger causality from SAB estimates.40

Recent European studies using SAB models have repeatedly found that adolescents select friends with similar levels of smoking behavior.5,6,13–15 Evidence is less consistent for peer influence on smoking6,13,15 and for smoking as a source of popularity.6,14 For instance, of the 6 European countries Mercken et al. studied, only 2 displayed peer influence effects, whereas smoking enhanced popularity in 2 other countries.5 Taken together, prior research suggests that selection into friendships with similar peers is more widespread than is peer influence on smoking or smoking enhancing popularity. However, to our knowledge, no previously published studies have used this modeling strategy to examine smoking among US adolescents.

METHODS

We used a school-based network of US adolescents contained in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health).41 Our longitudinal network analysis requires high coverage of the target population, which necessitates observations for all students in a school over time. We focused on 509 students observed at 2 time points within a high school—Jefferson High—that has been the focus of previous studies of romantic and sexual networks42 and sexually transmitted disease diffusion.43 We chose this school because the combination of its size with the fact that its smoking prevalence is greater than is that of other Add Health schools provides the greatest power to test the hypothesized effects. In addition, the school is racially homogeneous (97% White), which allows a more parsimonious model, free of the confounding effects of race and ethnicity on smoking and friend selection. The response rate for the initial school interview was 75%, of whom 81% were included in the 2 subsequent in-home interviews (approximately 1 year apart), which provide the measures for our analysis. Students in our sample reported more friends than did students who left the study, but their smoking rates were no different.

Measures

Our outcome was smoking frequency in the past 30 days (0 = never, 1 = 1–11 days, 2 = 12 or more days). Predictors of smoking included gender (0 = male, 1 = female), age, delinquency, alcohol use, grade point average (GPA), and parents’ smoking (0 = neither parent, 1 = at least 1 parent). We coded delinquency as the frequency of 13 delinquent activities in the past 12 months. We coded alcohol use in the past year as none (0), twice a week or less (1), or more than twice a week (2). GPA was the mean of the student's grades in math, science, history, and English. Predictors of friend selection included gender, age, delinquency, alcohol use, GPA, and, for each dyad, the number of extracurricular activities in common. We measured all controls at time 1. We obtained directed school-level friendship networks by asking students to nominate up to 5 male and 5 female friends. Inadvertently, the time 1 interview restricted fewer than 5% of students to nominate only 1 male and 1 female friend. To control for this anomaly, our model included a dummy variable indicating which question version the adolescent received (0 = full, 1 = truncated).

Analysis

We estimated the SAB model using the RSiena package within the R statistical program (University of Oxford, Department of Statistics, Oxford, UK).44 A full elaboration of the SAB model is described elsewhere.5,35 The SAB model consists of 2 functions, representing changes in smoking behavior and friendship ties.13 The smoking function includes effects to predict changes in smoking over time. The smoking function tests 2 types of network effects on smoking: influence, which takes into account friends’ smoking; and popularity, which considers the number of friends but not their smoking. We estimated peer influence with an effect representing the average similarity in smoking behavior between the respondent (ego) and the respondent's friends (alters). We tested the effect of popularity on smoking with the in-degree effect, which counts the number of students nominating ego as a friend. We included a quadratic version of the in-degree effect (in-degree squared) to test whether the effect of popularity on smoking was nonlinear. The smoking function also includes controls for several individual attributes that may cause changes in smoking. We mean-centered all individual-level measures before model estimation.

The friend selection function includes effects that predict which friendship ties form or persist over time versus dissolving or failing to form. For the sake of simplicity, we refer to these as “selection” effects. The smoking similarity effect tests whether friendships were more likely among students with more similar (vs dissimilar) smoking behavior. The smoking alter effect tests whether students with higher levels of smoking were more likely to be selected as a friend (i.e., the effect of smoking on one's popularity). We used a quadratic term (smoking alter squared) to test whether the effect of smoking on popularity was nonlinear. The smoking ego effect represents how smoking affects the number of friends students nominated.

The friend selection function includes additional similarity, alter, and ego effects as controls for selection on the basis of other individual attributes (e.g., gender, age). Other effects are endogenous network processes (i.e., reciprocity, transitivity, popularity) that can also form the basis for friendships. Accounting for friend selection through such processes is necessary to avoid biased estimates of friend selection related to smoking and peer influence.13 The SAB model assumes that individuals have multiple opportunities to change friendships and smoking frequency between the 2 observed time points. The number of opportunities is estimated by a rate effect in each function. We used the rate effect only for estimation purposes; it does not represent the actual number of changes. The model also requires effects representing average tendencies, akin to intercepts in a linear model (i.e., average number of friendships in the selection function, linear and quadratic terms in the smoking function).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the measures used in our analysis. At time 1, 52.0% of adolescents reported smoking at least once in the past 30 days. This increased to 56.0% a year later, at time 2. Between observations, 19.7% of adolescents increased their level of smoking, whereas 13.3% decreased their smoking. Regarding network characteristics, students had approximately 3 friends on average at each time point. The Jaccard index was 0.24, indicating that approximately one quarter of the friendships reported at either time point were present at both time points, which is a reasonable amount of change for our analysis.35

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Statistics for Add Health Sample (n = 509): National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 1994–1996

| Measure | Range | Mean (SD) or % |

| Individual | ||

| Past 30-d smoking (time 1), d | 0–2 | 0.84 (0.88) |

| 0 (never) | 48.02 | |

| 1 (1–11) | 19.84 | |

| 2 (≥ 12) | 32.14 | |

| Past 30-d smoking (time 2), d | 0–2 | 0.93 (0.89) |

| 0 (never) | 43.79 | |

| 1 (1–11) | 19.72 | |

| 2 (≥ 12) | 36.49 | |

| Truncated friendship roster | 0–1 | 4.30 |

| Female | 0–1 | 46.60 |

| Age | 14–19 | 15.39 (0.99) |

| Alcohol use | 0–2 | 1.05 (0.76) |

| Delinquency | 0–2 | 4.53 (5.01) |

| GPA | 1–4 | 2.64 (0.75) |

| Parent smoking | 0–1 | 0.78 (0.41) |

| Incoming friends | ||

| Time 1 | 0–15 | 3.38 (2.91) |

| Time 2 | 0–14 | 2.82 (2.73) |

| Outgoing friends | ||

| Time 1 | 0–10 | 3.38 (2.02) |

| Time 2 | 0–9 | 2.82 (1.93) |

| Network | ||

| Reciprocity | ||

| Time 1 | 39.85 | |

| Time 2 | 37.80 | |

| Transitivity | ||

| Time 1 | 35.38 | |

| Time 2 | 28.58 | |

| Similarity | ||

| Time 1 | 0.53 | |

| Time 2 | 0.52 | |

Note. GPA = grade point average. Reciprocity is the percentage of outgoing friendship nominations (i→j) matched by an incoming tie (j←i). Transitivity equals the percentage of indirect ties (e.g., i indirectly reaches h; i→j→h) that are also direct (i→h). Similarity calculated as (Δ minus the average smoking difference within observed ties) divided by Δ, where Δ equals the range of smoking observed (i.e., 2).

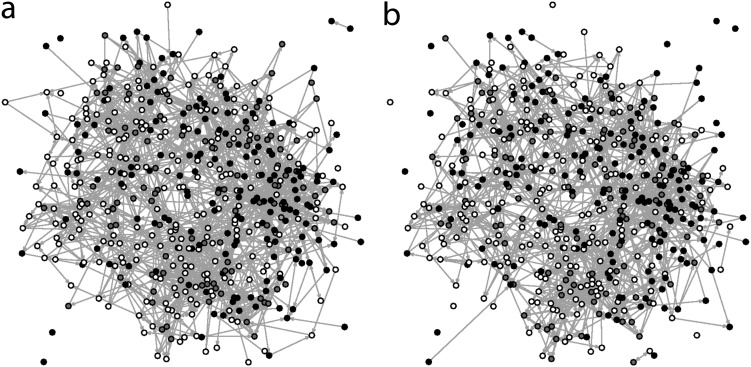

Figure 1 displays the network at each time point, with nodes shaded to represent smoking frequency. The network is displayed such that students who are closer in the network (i.e., socially proximate) are positioned closer together. Similarity on smoking among friends is evident in the concentration of nonsmokers on the left side of the network (white nodes) and the most frequent smokers on the right side of the network (black nodes).

FIGURE 1—

Friendship network at time points (a) 1 and (b) 2: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 1994–1996.

Note. Nodes shaded on the basis of smoking frequency in the past 30 days: white = 0; gray = 1–11; and black ≥ 12 days.

Table 2 shows the findings for the smoking function. The quadratic term, representing the distribution of smoking, is positive and significant. Because smoking is mean-centered, this indicates that nonsmoking or regular smoking is more common than is intermittent smoking (reflecting the distribution in Table 1). Of the individual attributes, only delinquency significantly predicted smoking behavior over time. Students with higher delinquency scores at baseline were more likely to increase their smoking (and less likely to decrease their smoking) from time 1 to time 2 than were those with lower delinquency scores.

TABLE 2—

Estimates From Stochastic Actor-Based Model Testing Smoking and Friendship Coevolution With Add Health Sample: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 1994–1996

| Effect | b (SE) |

| Smoking behavior function | |

| Rate | 2.065*** (0.270) |

| Linear shape | −0.107 (0.265) |

| Quadratic shape | 1.162*** (0.186) |

| Female | 0.155 (0.189) |

| Age | −0.005 (0.092) |

| Parent smoking | 0.016 (0.218) |

| Delinquency | 0.432* (0.183) |

| Alcohol | −0.102 (0.138) |

| GPA | −0.089 (0.132) |

| Average similarity | 2.883*** (0.855) |

| In-degree | −0.041 (0.139) |

| In-degree squared | 0.002 (0.012) |

| Friend selection function | |

| Rate | 10.241*** (0.505) |

| Rate: truncated roster | −1.178** (0.452) |

| Out-degree | −3.935*** (0.170) |

| Reciprocity | 1.916*** (0.085) |

| Transitive triplets | 0.515*** (0.035) |

| Popularity (square root of In-degree) | 0.290*** (0.037) |

| Extracurricular activity overlap | 0.275*** (0.060) |

| Female | |

| Similarity | 0.237*** (0.045) |

| Alter | −0.111* (0.046) |

| Ego | −0.039 (0.053) |

| Age | |

| Similarity | 1.004*** (0.125) |

| Alter | −0.009 (0.029) |

| Ego | −0.037 (0.031) |

| Delinquency | |

| Similarity | 0.147 (0.080) |

| Alter | −0.039 (0.040) |

| Ego | 0.019 (0.043) |

| Alcohol | |

| Similarity | 0.269** (0.101) |

| Alter | −0.028 (0.035) |

| Ego | −0.029 (0.039) |

| GPA | |

| Similarity | 0.706*** (0.133) |

| Alter | −0.054 (0.035) |

| Ego | −0.019 (0.040) |

| Smoking | |

| Similarity | 0.683*** (0.126) |

| Alter | 0.130* (0.062) |

| Alter squared | 0.023 (0.171) |

| Ego | −0.039 (0.055) |

Note. GPA = grade point average.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (2-tailed tests).

In terms of peer influence, there was a significant positive effect of average similarity on smoking (b = 2.883; P < .001). This reveals that adolescents were likely to adopt smoking behavior that resembled their friends. However, the effects of in-degree and in-degree squared—representing popularity—were not significant. Thus, smoking frequency was not affected by the number of friends an adolescent had, but only by their smoking behavior. To understand the magnitude of the peer influence effect, consider a nonsmoking adolescent whose friends all smoke. Given the opportunity to change, the odds of adolescents becoming intermittent smokers are 4.23 times greater than are the odds of their remaining nonsmokers (calculated as exp[b/smoking range] = exp[2.883/2]).44

Regarding friend selection, the controls for endogenous network processes were all significant in the expected direction. Adolescents were more likely to select peers who had previously selected them (reciprocity), peers with whom they shared a mutual friend (transitive triplets), and peers that many fellow students had previously selected (popularity). Additional controls indicate that adolescents were more likely to be friends if they were similar on gender, age, alcohol use, GPA, and activity participation. The negative female alter effect indicates that female adolescents were somewhat less popular than were male adolescents. Otherwise, there were no differences in the tendency to select friends or to be selected on the basis of the controls for individual characteristics.

Regarding how smoking affects friend selection, we observed a significant positive effect for smoking similarity (b = 0.683; P < .001). This effect offers evidence that adolescents were more likely to select each other as friends to the extent they engaged in similar levels of smoking. We also found a significant, positive smoking alter effect (b = 0.130; P < .05), and nonsignificant smoking alter squared effect. This suggests that adolescents were more likely to nominate students with higher levels of smoking as a friend. Thus, smoking was a source of popularity within the network. The nonsignificant smoking ego effect indicates that smoking did not affect the number of friends adolescents nominated.

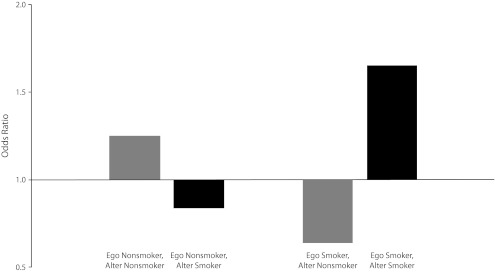

Our results for selection indicate that smoking helps drive friend selection through both popularity and similarity. To fully comprehend these effects, one must consider them in conjunction. To facilitate this, we calculated predicted odds ratios to represent friend selection likelihood on the basis of ego's and alter's joint smoking behavior.35 As shown in Figure 2, students displayed a clear tendency to select friends with a similar level of smoking. For nonsmokers, the odds of selecting a nonsmoking friend were 1.25 times higher than were the odds of selecting a friend who smoked intermittently. For smokers, the odds of selecting a smoking friend were 1.65 times greater than were the odds of selecting an intermittent smoking friend. By contrast, the odds of a smoker selecting a nonsmoker and vice versa fall below 1.00, indicating that smokers and nonsmokers were less likely to select each other than to select intermittent smokers. Still, because smoking enhanced popularity, nonsmokers were 1.42 times more likely to nominate smokers as friends than were smokers to nominate nonsmokers.

FIGURE 2—

Odds ratios of friend selection on the basis of smoking frequency of ego and alter: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 1994–1996.

Note. Nonsmoker defined as no smoking in past 30 days; smoker defined as smoking ≥ 12 of the past 30 days. We calculated odds ratios relative to the odds of ego (i.e., respondent) selecting an alter (i.e., peer) with intermittent smoking (1–11 of the past 30 days). All other effects are held constant.

DISCUSSION

We examined smoking and friendship in a sample of US adolescents to determine whether associations between smoking and friendships were owing to effects of friends on smoking or effects of smoking on friend selection. We used a longitudinal network model that distinguished the directionality of effects by simultaneously estimating changes in smoking behavior and selection into friendships. As expected, adolescents influenced each other's smoking frequency and selected friends with similar levels of smoking. Thus, both selection and peer influence contributed to similarity on smoking among friends. In terms of popularity, we found that students were likely to select smokers rather than nonsmokers as friends. We found no evidence that popularity affected smoking behavior.

More generally, our results offer evidence that smoking and friendships are associated though a complex set of causal pathways.8 Both friend selection and peer influence play a role in the development of adolescent smoking. Consequently, interventions aimed at reducing adolescent smoking should focus on the dynamics of friendship development and peer influence as intertwined processes. Our peer influence findings offer support for prevention programs designed using the social influence model.45,46 Moreover, our finding that smoking enhanced popularity suggests it may be useful to consider interventions aimed at reducing adolescents’ attraction to peers who smoke. That is, one could target the friend selection process in an effort to prevent adolescents from pursuing friendships with peers who smoke.

Key to developing a successful strategy is identifying why smoking increases popularity. We may need to distinguish whether the attraction of smokers is because of smoking itself or because of other status-inducing attributes correlated with smoking, such as perceived maturity.47 In addition to reducing the opportunity for smokers to negatively influence nonsmokers, such a strategy may drive smokers to quit should they realize smoking is diminishing their social status. However, this may have the unintended consequence of preventing positive peer influence on smoking (e.g., nonsmokers influencing smokers to quit). Clearly, more research is needed to fully understand these complex processes. Of particular benefit would be an examination of the relative role of peer influence in both the initiation and cessation of smoking.

Strengths

The social network perspective offered several advantages. First was the capacity to separately estimate how smoking affects friendship and how friends affect adolescents’ smoking, which provides a more complete assessment of this complex interrelation.

Second, the SAB model offers more reliable estimates of peer influence on smoking that are free from homogeneity biases caused by friend selection on the basis of smoking. By explicitly modeling the interdependence between adolescents, the model overcomes violations to statistical assumptions that characterize prior research using more conventional linear models.

Third, the model allows unbiased estimates of the role of smoking in friend selection by controlling for alternative friendship mechanisms. The SAB model we used is still relatively new. It has been used to examine health outcomes that include depression16–18 and alcohol use48 in addition to smoking. However, there are far more health issues and related behaviors in which such models can offer new insights. Our work provides an early example of how this framework can shed new light on the social mechanisms that relate friendships to health behaviors.

Limitations

We considered the dynamics of smoking and friendship in a predominantly White, high smoking prevalence high school. Although results were consistent with patterns observed in more recent studies in Europe, it is important to test whether these effects are generalizable.

Given the lower smoking rates among adolescents today compared with when Add Health data were collected, a key question is whether the strong effects we observed also exist in schools with lower smoking rates. The higher smoking prevalence in Jefferson High may have been a reflection of a particular school context where peer influence processes were especially strong, resulting in greater diffusion of smoking. Conversely, high smoking prevalence may have magnified its role in friend selection and increased adolescents’ exposure to smoking peers, setting the stage for negative peer influence. Examining multiple schools is the only means to assess contextual and temporal variations in the smoking–friendship association.49

It would also be worthwhile to consider friendships that extend outside the school grounds. The smoking behavior of such friends may differ from that of in-school friends and may be an important alternative peer influence. Furthermore, the identification of causal peer effects requires controlling for any shared environmental factors that may both promote friendships and affect smoking.13,39

Conclusions

By offering a more detailed account of friendship and smoking dynamics, our results offer a new perspective on smoking and friend selection with practical implications for identifying alternative intervention points and strategies to combat adolescent smoking and other substance use.

Our models controlled for coparticipation in extracurricular activities, but it would be worthwhile to consider other activity spaces,50 particularly those outside school where adolescents regularly congregate. With suitable data, the SAB model can test for such effects as well as other nuances of peer influence and friend selection. For example, the model can test whether peer influence on smoking is moderated by individual attributes or friendship characteristics (e.g., best friends)51; whether smokers are more attractive to particular types of adolescents, such as social isolates; and how school features, such as extracurricular activities, may serve as protective factors by inhibiting negative peer influence.

The SAB model can also test alternative explanations for selection on smoking, for instance whether adolescents are drawn together on the basis of similarity in smoking-related cognitions or other attitudes. Answering questions such as these can provide greater leverage to develop strategies to counter adolescent smoking.

Acknowledgments

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development supported this research (grant R21-HD060927).

We used data from Add Health, a project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant P01-HD31921), with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health Web site (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth).

We express our appreciation to the members of the Arizona State University Structural Dynamics Working Group for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because we used secondary data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2009. MMWR Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(26):797–801 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ennett ST, Bauman KE. Peer group structure and adolescent cigarette smoking: a social network analysis. J Health Soc Behav. 1993;34(3):226–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander C, Piazza M, Mekos D, Valente T. Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(1):22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercken L, Snijders TAB, Steglich C, de Vries H. Dynamics of adolescent friendship networks and smoking behavior: social network analyses in six European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1506–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steglich C, Sinclair P, Holliday J, Moore L. Actor-based analysis of peer influence in A Stop Smoking In Schools Trial (ASSIST). Soc Networks. In press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(suppl 1):S37–S55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakon CM, Hipp JR, Timberlake DS. The social context of adolescent smoking: a systems perspective. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(7):1218–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauman KE, Ennett ST. On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: commonly neglected considerations. Addiction. 1996;91(2):185–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandel DB. Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescent friendships. Am J Sociol. 1978;84(2):427–436 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall JA, Valente TW. Adolescent smoking networks: the effects of influence and selection on future smoking. Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):3054–3059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snijders TAB. The statistical evaluation of social network dynamics. : Sobel ME, Becker MP, Sociological Methodology. Boston: Basil Blackwell; 2001:361–395 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steglich C, Snijders TAB, Pearson M. Dynamic networks and behavior: separating selection from influence. Sociol Methodol. 2010;40(1):329–393 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiuru N, Burk WJ, Laursen B, Salmela-Aro K, Nurmi J. Pressure to drink but not to smoke: disentangling selection and socialization in adolescent peer networks and peer groups. J Adolesc Health. 2011;33(6):801–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercken L, Candel M, Willems P, de Vries H. Disentangling social selection and social influence effects on adolescent smoking: the importance of reciprocity in friendships. Addiction. 2007;102(9):1483–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer DR, Kornienko O, Fox AM. Misery does not love company: network selection mechanisms and depression homophily. Am Sociol Rev. 2011;76(5):764–785 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiuru N, Burk WJ, Laursen B, Nurmi JE, Salmela-Aro K. Is depression contagious? A test of alternative peer socialization mechanisms of depressive symptoms in adolescent peer networks. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(3):250–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Zalk MH, Kerr M, Branje SJ, Stattin H, Meeus WH. It takes three: selection, influence, and de-selection processes of depression in adolescent friendship networks. Dev Psych. 2010;46(4):927–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moody J, Feinberg ME, Osgood DW, Gest SD. Mining the network: peers and adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(4):324–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valente TW, Unger JB, Johnson CA. Do popular students smoke? The association between popularity and smoking among middle school students. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(4):323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valente TW, Gallaher P, Mouttapa M. Using social networks to understand and prevent substance use: a transdisciplinary perspective. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39(10–12):1685–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eiser JR, Morgan M, Gammage P, Brooks N, Kirby R. Adolescent health behaviour and similarity-attraction: friends share smoking habits (really), but much else besides. Br J Soc Psychol. 1991;30(pt 4):339–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engels RC, Knibbe RA, Drop MJ, de Haan YT. Homogeneity of cigarette smoking within peer groups: influence or selection? Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(6):801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher LA, Bauman KE. Influence and selection in the friend–adolescent relationship: findings from studies of adolescent smoking and drinking. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1988;18(4):289–314 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrad KM, Flay BR, Hill D. Why children start smoking cigarettes: predictors of onset. Br J Addict. 1992;87(12):1711–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Andersen MR, Rajan KB, Leroux BG, Sarason IG. Childhood friends who smoke: do they influence adolescents to make smoking transitions? Addict Behav. 2006;31(5):889–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd-Richardson EE, Papandonatos G, Kazura A, Stanton C, Niaura R. Differentiating stages of smoking intensity among adolescents: state-specific psychological and social influences. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(4):998–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simons-Morton B, Chen RS. Over time relationships between early adolescent and peer substance use. Addict Behav. 2006;31(7):1211–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong Aet al. The peer context of adolescent substance use: findings from a social network analysis. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16(2):159–186 [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:415–444 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moody J, Brynildsen WD, Osgood DW, Feinberg ME, Gest S. Popularity trajectories and substance use in early adolescence. Soc Networks. 2011;33(2):101–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Killeya-Jones LA, Nakajima R, Costanzo PR. Peer standing and substance use in early-adolescent grade-level networks: a short-term longitudinal study. Prev Sci. 2007;8(1):11–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michell L. Loud, sad or bad: young people's perceptions of peer groups and smoking. Health Educ Res. 1997;12(1):1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michell L, Amos A. Girls, pecking order and smoking. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(12):1861–1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snijders TAB, van de Bunt GG, Steglich CEG. Introduction to stochastic actor-based models for network dynamics. Soc Networks. 2010;32:44–60 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: the case of adolescent cigarette smoking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67(4):653–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An W. Models and methods to identify peer effects. : Scott J, Carrington PJ, The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis. London: Sage; 2011:515–532 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2249–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen-Cole E, Fletcher JM. Detecting implausible social network effects in acne, height, and headaches: longitudinal analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Granger CWJ. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica. 1969;37(3):424–438 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris KM. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Waves I & II, 1994–1996 [machine-readable data file and documentation]. Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bearman P, Moody J, Stovel K. Chains of affection: the structure of adolescent romantic and sexual networks. Am J Sociol. 2004;110(1):44–91 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moody J. The importance of relationship timing for diffusion. Soc Forces. 2002;81(1):25–56 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ripley RM, Snijders TAB, Preciado P. Manual for RSiena. Oxford: University of Oxford, Department of Statistics, Nuffield College; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valente TW, Hoffman BR, Ritt-Olson A, Lichtman K, Johnson CA. The effects of a social network method for group assignment strategies on peer led tobacco prevention programs in schools. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(11):1837–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell R, Starkey F, Holliday Jet al. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1595–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(4):674–701 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knecht A, Snijders TAB, Baerveldt C, Steglich CEG, Raub W. Friendship and delinquency: selection and influence processes in early adolescence. Soc Dev. 2010;19(3):494–514 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilcox P. An ecological approach to understanding youth smoking trajectories: problems and prospects. Addiction. 2003;98(suppl 1):55–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mason MJ, Korpela K. Activity spaces and urban adolescent substance use and emotional health. J Adolesc. 2009;32(4):925–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: a decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(1):166–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]