Introduction

The concept of health care transition (HCT) was originally described as the “purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centered to adult-oriented health care systems… with the optimal goal of providing health care that is uninterrupted, coordinated, developmentally appropriate, psychologically sound, and comprehensive”.1 Though the importance of this concept has been reaffirmed,2–4 surveys of adult gastroenterologists5 and resident physicians in internal medicine and pediatrics6 demonstrate a lack of confidence and knowledge pertaining to transition of care. Transition from pediatric to adult-oriented providers remains an under-developed area in many fields,7 including gastroenterology.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic immune-mediated disorder which has been increasing in incidence and prevalence.8–12 While it has been reported across the age spectrum, the clinical presentation varies by age, and a disproportionate number of patients are either children or young adults.8, 9, 13–16 Although there are some effective treatments for EoE condition, there is not currently a cure and patients will continue to face ongoing symptoms, evaluation, treatment, and disease management strategies as they transition to adulthood. However, the issue of formally transitioning care from a pediatric to an adult-focused provider in EoE has never been discussed in the medical literature.

The purpose of this report is to describe a series of adolescents with EoE in order to highlight both general and disease-specific issues related to HCT, review barriers to HCT, outline the ideal components of a HCT program, and propose a theoretic framework for transition of care in EoE as a basis for future program development and research.

Illustrative case presentations

Patient #1 was a 21 year old woman diagnosed with EoE at 17 after presenting with heartburn, dysphagia, and epigastric discomfort (Table 1). She had a clinical and histologic response to treatment with swallowed fluticasone and omeprazole. Prior evaluation showed allergies to nuts, soy, and legumes, and she attempted to maintain a targeted elimination diet but was not always consistent with this. She was referred to our adult GI clinic after direct email communication with her pediatric gastroenterologist, and came to clinic by herself. At that time, she had been non-adherent with her medication regimen and was having active symptoms. Repeat endoscopic evaluation confirmed active EoE, and after reinstituting her medications and emphasizing the importance of allergen avoidance, she had a symptomatic and histologic response. However, she did not come for her scheduled follow-up appointments at the adult GI clinic because she said she was feeling well.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the cases

| Patient number |

Age at clinic visit |

Sex | Race | Highest education |

Insurance | Parental marital status |

Parental education level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | Female | Caucasian | in college | Commercial | Married | F: College |

| (parent’s plan) | M: College | ||||||

| 2 | 18 | Female | Caucasian | in HS | none | Married | n/a |

| 3 | 17 | Male | Caucasian | in HS | Commercial | Married | F: Grad school |

| (parent’s plan) | M: Grad school | ||||||

| 4 | 20 | Male | Caucasian | in college | Commercial | Married | F: Grad school |

| (parent’s plan) | M: College |

Abbreviations: HS = high school; F = father; M = mother; grad = graduate

Patient #2 was an 18 year old woman diagnosed with EoE at 8, with symptoms of epigastric discomfort and intermittent dysphagia. She previously had a symptomatic and histologic response to swallowed topical steroids, but had trouble remembering to take them. She too was referred to adult GI clinic after communication with her pediatric gastroenterologist, and had active symptoms due to running out of her medications. She came to the appointment with her parents, but they were over an hour late because they got lost. Plans were made to restart therapy and repeat an endoscopy, but the appointment was rescheduled 3 times due to insurance issues, and the patient has not returned for follow-up.

Patient #3 was a 17 year old boy recently diagnosed with EoE after an acute food impaction; otherwise he had only intermittent symptoms of dysphagia. He presented to the emergency room and required urgent upper endoscopy which was performed by pediatric surgery. Bolus clearance and Savary dilation were performed, but esophageal biopsies were not obtained. His parents arranged consultation in adult GI clinic and accompanied the patient, and repeat endoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of EoE. After the initial dilation, the patient was asymptomatic, did not understand why he required follow-up, and was reluctant to take medications or undergo additional evaluation.

Patient #4 was a 20 year old man diagnosed with EoE at the age of 10 when symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia persisted after Nissen fundoplication. He was referred to adult GI clinic by his pediatrician without direct communication with his prior pediatric gastroenterologist and without pertinent medical records for review. His mother was present and provided some history. He required chronic swallowed fluticasone therapy (> 8 years) to maintain symptom control. His prior evaluation found an egg allergy, and he followed a targeted elimination diet. Since his symptoms were controlled with fluticasone, he did not want to consider alternative agents and deferred additional endoscopic evaluation so he would not miss any college classes.

These four cases highlight many of the issues related to transition of care from the pediatric to adult setting in EoE (Table 2). For example, without a formal transition program in place there was sub-optimal communication between pediatric- and adult-focused providers, patients and families were not familiar with adult clinic logistics, patients did not have adequate knowledge about their medical condition, non-adherence to therapy was common, and readiness for transition was not assessed.

Table 2.

Summary of cases and issues related to transition of care in EoE

| Patient number |

Age of EoE diagnosis |

Years since EoE diagnosis |

Percentage of life with EoE diagnosis |

Symptoms | Active symptoms at the time of transfer? |

Direct communication for referral? |

Parents present at first visit? |

Taking meds as directed? |

On dietary therapy? |

Transition issues* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | 4 | 19 | R, AP, D | yes | yes | no | no | yes | 1, 4, 8, 9, 10 |

| 2 | 8 | 10 | 56 | AP, D | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12 |

| 3 | 17 | 0.5 | 3 | D, FI | no | no | yes | yes | no | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 11 |

| 4 | 10 | 10 | 50 | D, R | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11 |

Abbreviations: D = dysphagia; FI = food impaction; R = reflux/heartburn; AP = abdominal pain

Transition issues:

1. No formal transition program

2. Inadequate (or absent) communication with referring

3. Not familiar with clinic location and logistics

4. Transition readiness not assessed

5. Inadequate knowledge about medical condition

6. Inadequate knowledge about personal medical history

7. Importance and implication of intermittent symptoms not adequately understood

8. Non-adherence to medications

9. Non-adherence to follow-up appointments

10. Dietary therapy with nutritional support needs

11. Yet to develop independence from parents

12. Inadequate insurance coverage

Health care transition from pediatric- to adult-focused systems

HCT is an increasingly recognized area of importance.4 Interestingly, there have been no studies regarding HCT in EoE despite the large number of children and adolescents with this condition who will need adult providers as they age. However, review of the current HCT literature in patients with liver and solid organ transplant,17–21 inflammatory bowel disease,5, 22–24 cystic fibrosis,25 chronic kidney disease,6, 26–28 juvenile arthritis,29 congenital heart disease,30 and diabetes31 reveals several recurring themes which are applicable to transition in EoE, including barriers to transitional care and program elements required for success.21

Barriers to health care transition

Barriers to providing HCT can be categorized as patient/parent-specific (issues related to development and adolescence, parental involvement, or familial acceptance of the need for an adult provider), provider-specific (issues related to training and knowledge, communication between providers, and interest in HCT), and systemic (issues related to insurance coverage, institutional support, funding, staffing, physical clinic space, and multidisciplinary collaboration) (Table 3).5, 6, 18, 19, 21, 23, 25, 29, 30, 32–38 Without an understanding of these barriers, design and implementation of a HCT program may be unsuccessful.

Table 3.

General barriers to successful transition of care

Patient- and parent-specific barriers

|

Provider-specific barriers

|

Systematic barriers

|

Required elements in health care transition programs

Four general models for transitional care have been noted.34 “Direct transition” involves transfer from the pediatric clinic to the adult clinic with or without information sharing or communication between providers. This model is the default pathway most commonly utilized in practice, and as illustrated by the cases above, is felt to be inadequate. Other models include the following: “sequential transition” where patients are seen in specially designed adolescent or young adult clinics; “developmental transition” where the adolescent is trained to achieve critical milestones in the understanding of their health condition; and “professional transition” where there is formal transfer of expertise between pediatric- and adult-focused providers. The optimal approach to HCT most likely combines features from the latter three models.34

A number of prior studies corroborate that a multi-faceted approach is needed and have highlighted the ideal elements required for a successful transition program (Table 4). In general, the concept of HCT should be introduced in early adolescence, but details and timing of transition should be individualized.18, 25, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38 Throughout the literature, the importance of a dedicated transition coordinator is emphasized. This person ensures that the patient is engaged in developmentally appropriate self-management and self-advocacy tasks to prepare to interact with adult-focused providers. The coordinator is present in the pediatric clinic and continues in the adult clinic until the patient is fully integrated. In reality, obtaining and funding this coordinator might be the single most important barrier to the establishment of transitional care programs.18, 23, 25, 32, 33, 35, 36

Table 4.

Essential elements of transition of care

General transition program elements18, 25, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38

|

Dedicated transition coordinator18, 23, 25, 32, 33, 35, 36

|

Critical milestone assessment18, 24, 37

|

Patient education18, 23, 34, 35

|

Parent education18

|

Provider education and engagement5, 6, 18, 21, 38

|

Ongoing transition readiness assessment is also crucial to ensure that adolescents achieve critical milestones before they transfer to adult care.18, 24 Examples of milestones include demonstration of understanding of their medical condition, knowledge of medications and obtaining refills, scheduling appointments, maintaining health records, and functioning independently in the health care setting. Standardized assessment tools are being developed to aid in this process, and require a multifaceted educational program for the patients, the parents, and the providers.18, 24, 29, 37 In addition, patients33 and their parents19, 37 support the use of transitional clinics where patients are introduced to adult providers before they actually transfer care.

Health care transition in EoE

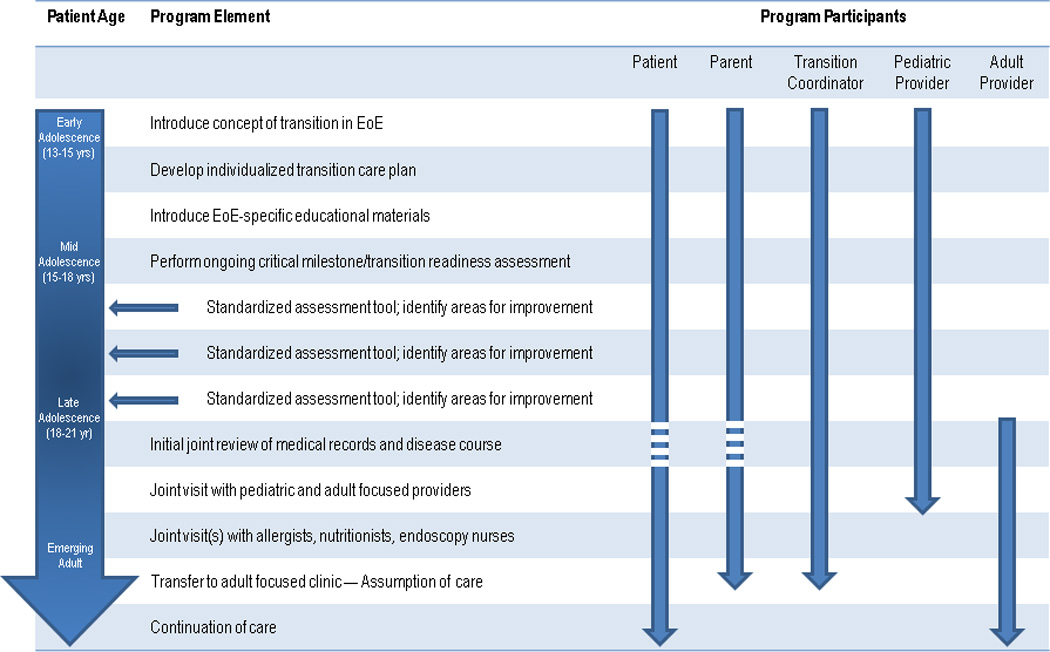

With this background, we propose a disease-specific approach to HCT in EoE (Figure 1). While many of the general tenets of transition are applicable to EoE, there are disease-specific features that complicate HCT in EoE. First, there is not a “simple” transition from one pediatric to one adult provider in EoE. Instead, there is often a multidisciplinary team of gastroenterologists, allergists, and dieticians that must be considered. There may be enteral feeding tubes, special nutritional formulations, and home care companies involved as well. Frequent endoscopies are often required to assess and manage disease manifestations, and this adds another layer of logistics and personnel. In addition, while the cases presented in this paper are somewhat homogenous in terms of race, family support, and education level, it is important to consider patient racial/ethnic diversity, parental marital status and education, and family resources when individualizing a transition program for each patient.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for disease-specific health care transition program in eosinophilic esophagitis. This is a dynamic model with a progression of age-specific activities involving the patient, parent, transition coordinator and pediatric and adult providers.

The EoE HCT program would introduce the concept of transition during early adolescence. Working with a transition coordinator, the patient, parents, and pediatric provider would develop an individualized HCT plan based on a patient’s specific characteristics and needs, and begin to utilize EoE-specific educational materials. During the mid and late adolescent period, the pediatric team would perform routine critical milestone assessment using a standardized tool to identify areas where improvement is needed. This is the time frame in which knowledge and self-care skills are most developed, but readiness for HCT could start even earlier with younger children learning the name of their condition and medications. When transition readiness approaches, the transition coordinator, pediatric providers, and adult providers would meet to perform a joint review of the medical records and disease course. This meeting would be followed by a joint pediatric/adult provider visit with the patient, parents, and transition coordinator in a specialized EoE transition clinic setting. Additional joint visits with members of the interdisciplinary team, tours of the adult clinic and endoscopy suite, and other special sessions would be scheduled as needed. When all parties are comfortable with transition readiness, care can be assumed by the adult provider and over time as parents become less involved, care will be continued with the patient and adult provider.

This proposed transition program in EoE provides a general framework that builds on the experience of HCT in other disease states, addresses needs specific to EoE, and has been constructed to avoid many of the potential barriers in transition of care. We anticipate that there may still be systemic barriers to implementation, and ongoing work will be required to identify funding mechanisms and develop EoE disease-specific protocols and materials to fully institute all aspects of this program. We are planning to pilot this proposed EoE HCT program at our own institution to examine these issues in more detail and show that this approach will improve outcomes.

Conclusions

Health care transition for adolescents with chronic medical conditions has been examined in cystic fibrosis, renal failure, inflammatory bowel disease, and other conditions. Without a formal HCT program, communication between providers care can be disjointed, costly tests may be repeated, patients may be lost to follow-up, and adverse health outcomes may occur. While EoE seems to represent an ideal condition in which to apply the principles of HCT, to our knowledge this has yet to be proposed in the medical literature. Because a large cohort of pediatric patients with EoE will age into adolescence and adulthood over the next decade, we believe that HCT in EoE is an under-studied area that needs to be addressed. We have provided an initial framework for an HCT program in EoE which will be pursued at our institution, recognizing common barriers and incorporating a number of elements considered essential for success. Individual aspects of this program will need additional development and testing, and outcomes must be tracked prospectively to demonstrate the benefits we hypothesize will result from this carefully coordinated effort.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was funded, in part, by NIH award number KL2RR025746 from the National Center for Research Resources and a Junior Faculty Development Award from the American College of Gastroenterology. The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Abbreviations

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- GI

gastrointestinal

- HCT

health care transition

- UNC

University of North Carolina

Footnotes

Author contributions (all authors approved the final draft):

Dellon, ES: study concept and design; literature review; program design; manuscript drafting/revision

Jones: literature review; program design; manuscript drafting/revision

Martin: program design; critical revision

Kelly: program design; critical revision

Kim: program design; critical revision

Freeman: program design; critical revision

Dellon, EP: program design; critical revision

Ferris: program design; supervision; critical revision

Shaheen: study concept and design; supervision; critical revision

Potential competing interests: No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors

References

- 1.Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(7):570–576. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen DS, Blum RW, Britto M, Sawyer SM, Siegel DM. Transition to adult health care for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(4):309–311. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(6):548–553. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.202473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(1):61–65. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31816d71d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MS, O'Hare K. Residency training in transition of youth with childhood-onset chronic disease. Pediatrics. 2010;126(Suppl 3):S190–S193. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1466P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonagh JE, Kelly DA. The challenges and opportunities for transitional care research. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14(6):688–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(4):1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):940–941. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200408263510924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(2):418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;104:2695–2703. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King J, Khan S. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Perspectives of Adult and Pediatric Gastroenterologists. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzka DA. Demographic data and symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2007.09.005. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putnam PE. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children: clinical manifestations. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18(1):11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2007.09.007. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annunziato RA, Emre S, Shneider B, Barton C, Dugan CA, Shemesh E. Adherence and medical outcomes in pediatric liver transplant recipients who transition to adult services. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11(6):608–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell LE, Bartosh SM, Davis CL, et al. Adolescent Transition to Adult Care in Solid Organ Transplantation: a consensus conference report. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(11):2230–2242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anthony SJ, Martin K, Drabble A, Seifert-Hansen M, Dipchand AI, Kaufman M. Perceptions of transitional care needs and experiences in pediatric heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(3):614–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annunziato RA, Parkar S, Dugan CA, et al. Brief report: Deficits in health care management skills among adolescent and young adult liver transplant recipients transitioning to adult care settings. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(2):155–159. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonagh JE, Kaufman M. Transition from pediatric to adult care after solid organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(5):526–532. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32832ffb2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodhand J, Dawson R, Hefferon M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in young people: the case for transitional clinics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(6):947–952. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung Y, Heyman MB, Mahadevan U. Transitioning the adolescent inflammatory bowel disease patient: Guidelines for the adult and pediatric gastroenterologist. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1002/ibd.21576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benchimol EI, Walters TD, Kaufman M, et al. Assessment of knowledge in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease using a novel transition tool. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(5):1131–1137. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuchman LK, Schwartz LA, Sawicki GS, Britto MT. Cystic fibrosis and transition to adult medical care. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):566–573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferris ME, Mahan JD. Pediatric chronic kidney disease and the process of health care transition. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(4):435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris ME. Adolescents and emerging adults with chronic kidney disease: their unique morbidities and adherence issues. Blood Purif. 2011;31(1–3):203–208. doi: 10.1159/000321854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warady BA, Ferris M. The transition of pediatric to adult-centered health care. Nephrol News Issues. 2009;23(10):49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw KL, Southwood TR, McDonagh JE. Development and preliminary validation of the 'Mind the Gap' scale to assess satisfaction with transitional health care among adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33(4):380–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reid GJ, Irvine MJ, McCrindle BW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of successful transfer from pediatric to adult health care among a cohort of young adults with complex congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):e197–e205. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Beaufort C, Jarosz-Chobot P, Frank M, de Bart J, Deja G. Transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care: smooth or slippery? Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(1):24–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fredericks EM. Nonadherence and the transition to adulthood. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(Suppl 2):S63–S69. doi: 10.1002/lt.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCurdy C, DiCenso A, Boblin S, Ludwin D, Bryant-Lukosius D, Bosompra K. There to here: young adult patients' perceptions of the process of transition from pediatric to adult transplant care. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(4):309–316. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonagh JE. Growing up and moving on: transition from pediatric to adult care. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9(3):364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owen P, Beskine D. Factors affecting transition of young people with diabetes. Paediatr Nurs. 2008;20(7):33–38. doi: 10.7748/paed2008.09.20.7.33.c6706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paone MC, Wigle M, Saewyc E. The ON TRAC model for transitional care of adolescents. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(4):291–302. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutishauser C, Akre C, Suris JC. Transition from pediatric to adult health care: expectations of adolescents with chronic disorders and their parents. Eur J Pediatr. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suris JC, Akre C, Rutishauser C. How adult specialists deal with the principles of a successful transition. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(6):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]