Abstract

Objective

Many trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence, yet few studies have examined why particular treatments are effective. This study was designed to evaluate whether drink refusal training was an effective component of a combined behavioral intervention (CBI) and whether change in self-efficacy was a mechanism of change following drink refusal training for individuals with alcohol dependence.

Method

The current study is a secondary analysis of data from the COMBINE study, a randomized clinical trial that combined pharmacotherapy with behavioral intervention in the treatment of alcohol dependence. The goal of the current study was to examine whether a drink refusal skills training module, administered as part of a 16-week CBI (n=776; 31% female, 23% non-White, average age=44) predicted changes in drinking frequency and self-efficacy during and following the CBI, and whether changes in self-efficacy following drink refusal training predicted changes in drinking frequency up to one year following treatment.

Results

Participants (n=302) who received drink refusal skills training had significantly fewer drinking days during treatment (d=0.50) and up to one year following treatment (d=0.23). In addition the effect of the drink refusal skills training module on drinking outcomes following treatment was significantly mediated by changes in self-efficacy, even after controlling for changes in drinking outcomes during treatment (proportion mediated = 0.47).

Conclusions

Drink refusal training is an effective component of CBI and some of the effectiveness may be attributed to changes in client self-efficacy.

Keywords: self-efficacy, drink refusal skills training, drinking outcomes, alcohol dependence, mechanisms of change

Randomized controlled trials have been considered the gold standard for conducting psychotherapy outcome research for the past 30 years. Across several disorders and treatment types these trials have generally found that many forms of psychotherapy are equally effective in promoting therapeutic change. Given that many effective treatments have been developed a critical next step for psychotherapy research is to focus more attention on what components of treatment are more or less effective and the processes by which change occurs during successful treatment (Kazdin, 2009).

Rosenzwieg (1936) proposed that “implicit common factors” (p. 412) explain psychotherapy outcomes across diverse treatments and numerous trials have shown that small outcome differences across different treatments are best explained by ingredients common to all treatments ( e.g., therapeutic alliance; see Wampold, 2001; Wampold, Mondin, Moody, Stich, & Ahn, 1997). Yet, others contend that specific treatment elements are a critical component of empirically supported treatments (Beutler, 2002; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). Gaining a better understanding of whether and why specific treatment elements facilitate change is an important goal for 21st century psychotherapy outcome research. The goal of the current study was to examine the outcomes of a drink refusal skills intervention that was delivered as one component of a combined behavioral intervention in the COMBINE study (2003); a multisite trial evaluating pharmacotherapy and behavioral intervention in the treatment of alcohol dependence. In addition, we were interested in examining self-efficacy as a potential mechanism of change following drink refusal training.

Kazdin (2007, 2009) identified several important reasons for studying the therapeutic mechanisms of change following treatment. Given the multitude of available empirically supported treatments Kazdin (2009) noted that it is important to understand what treatment elements are the key active ingredients in facilitating change. Improved knowledge about change mechanisms could also provide the opportunity to further refine existing treatments to “trigger critical change processes” (p. 418) and could provide the opportunity to disseminate evidence-based treatments with added information on what ingredients of treatment are particularly critical to include. Likewise, practitioners could be informed about how specific treatment elements are supposed to work, thus providing the opportunity for practitioners to continuously monitor whether their intervention is having an effect on the intended change mechanism. Finally, understanding how and why a specific treatment is effective could further elucidate treatment moderators (i.e., for who a particular treatment is going to be most effective).

Drink Refusal Skills Training

Drink refusal skills training emerged in the alcohol treatment literature three decades ago, amidst a broad movement of social skills training programs applied to various clinical targets (Hersen & Bellack, 1977). This approach rested on the notion that training individuals with alcohol dependence to invoke an alternative social response to alcohol-involved situations should deter temptations to drink, and enable clients to develop more adaptive social responses (O’Leary, O’Leary, & Donovan, 1976). Multiple early trials established efficacy of drink refusal skills training (e.g., Chaney, O’Leary, & Marlatt, 1978; Foy, Nunn, & Rychtarik, 1984) and later research identified cognitive ability as a moderator of its impact (Smith & McCrady, 1991), yet extant alcohol treatment literature offers limited documentation of why drink refusal training is effective among alcohol-dependent clientele. One hypothesis, supported by youth prevention research, is that drink refusal training enhances client self-efficacy for abstinence. Studies have documented that youth exposed to drink refusal skills training show increased self-efficacy, which in turn mediates treatment effects on subsequent alcohol use initiation and consumption (Komro, Perry, Williams, Stigler, Farbakhsh, & Veblen-Mortenson, 2001; Schinke, Cole & Fang, 2009). Likewise drink refusal self-efficacy has been shown to predict drinking behavior in adults (Oei, Hasking, & Philips, 2007) and learning theories provide conceptual support to hypothesize an association between drink refusal skills and self-efficacy in the prediction of drinking outcomes (Bradizza, Stasiewicz, & Maisto, 1994).

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy has been characterized as “what people believe they can do under given circumstances and task demand.” (pg. 37, Bandura, 1997). Bandura (1977) hypothesized that a person’s self-efficacy beliefs influenced the initiation and persistence of coping behavior in stressful situations (e.g., when offered a drink while trying to abstain from alcohol). Importantly, self-efficacy beliefs are formed by numerous sources, including performance (practicing the behavior), vicarious experience (watching others model the behavior), verbal persuasion (suggestion), and emotional arousal (attributions and exposure to stressful stimuli), all of which can be targeted within a behavioral treatment (Bandura, 1977). Indeed, numerous studies have found that individual self-efficacy tends to increase following cognitive behavioral treatments (e.g., Litt, Kadden, & Stephens, 2005; Loeber, Croissant, Heinz, Mann, & Flor, 2006 ) and other studies have found that self-efficacy beliefs tend to predict outcomes following treatment (e.g., Bradizza, Maisto, Vincent, Stasiewicz, Connors, & Mercer, 2009; Burleson & Kaminer, 2005; Casey, Newcombe, & Oei, 2005; Tate et al., 2008). Fewer studies have carefully examined whether change in self-efficacy following cognitive behavioral treatment significantly mediates the effect of treatment on treatment outcomes (see Hendricks, Delucchi, & Hall, 2010; Litt, Kadden, Kabela-Cormier, & Petry, 2008; Mensinger, Lynch, Tenhave, & McKay, 2007; Schmiege, Broaddus, Levin & Bryan, 2009). Yet, to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether a specific treatment component (e.g., drink refusal skills training) predicts increases in self-efficacy and whether self-efficacy mediates the association between a specific treatment component and the behavioral outcome.

Current Study

The COMBINE Study Research Group (2003) examined if treatment for individuals with alcohol dependence could be optimized by combining pharmacotherapy with medication management and/or combined behavioral intervention (CBI). Results indicated that individuals who were randomly assigned to receive medication management with naltrexone, CBI with placebo, or CBI with naltrexone had the highest percent days of abstinence during treatment, whereas those who received CBI without pharmacotherapy had the lowest percent days abstinent during treatment. One year after treatment there were no significant differences across groups in the primary outcome (Anton et al., 2006), although recent re-analyses of the COMBINE data using latent growth mixture modeling identified that those who received CBI, naltrexone, or CBI with naltrexone had better outcomes over time than those who received placebo and/or acamprosate (Gueorguieva et al., 2010).

The CBI, based primarily on motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy, incorporated nine distinct skills training modules that were individually tailored to the needs of each client. The individualization of the CBI provides the opportunity to examine change mechanisms following specific treatment modules designed to impact particular psychological processes. For example, in a recent re-analysis of the COMBINE study data Witkiewitz and colleagues (2011) found that receiving the Coping with Craving and Urges module resulted in fewer heavy drinking days and that receiving the module moderated the association between negative mood and heavy drinking during and following treatment. Furthermore, the study found that the moderating effect of the Coping with Craving and Urges module was mediated by changes in craving, the intended change mechanism. The current study was designed to examine drinking outcomes following drink refusal skills training and whether changes in self-efficacy mediated the effectiveness of drink refusal training.

Method

The current study was a secondary analyses of data from the COMBINE study (Anton et al., 2006), a multi-site randomized trial designed to examine the effect of combining pharmacotherapy (naltrexone, acamprosate, or placebo) with a behavioral intervention for alcohol dependence. Details of the rationale and procedures of the COMBINE study are described in detail elsewhere (COMBINE Study Research Group, 2003).

Participants

The sample was recruited from inpatient and outpatient alcohol treatment referrals at the study sites and throughout the community. The primary eligibility criteria were (1) alcohol dependence as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – Fourth Edition (APA, 1994), (2) 4 to 21 days of abstinence prior to the baseline evaluation, and (3) more than 14 drinks (woman) or 21 drinks (men) per week, with at least two heavy drinking days during a consecutive 30 day period within the 90 days prior to the baseline evaluation. Individuals were excluded if they had a history of other substance abuse (other than nicotine or cannabis) in the last 90 days (last 6 months for opiate abuse), had a psychiatric disorder requiring medication, or if they had an unstable medical condition. The final sample included 1,383 participants from 11 sites throughout the United States. The current study focused on data from the 776 individuals who were randomly assigned to the Combined Behavioral Intervention (CBI) condition. The subsample of those who were assigned to CBI was 31% female and 69% male. Approximately 23% of the subsample self-identified as ethnic minorities. Participants identified as follows: 76.7% non-Hispanic white, 10.7% Hispanic American, 7.7% African American, 1.5% American Indian or Alaska Native, 1.0% Multiracial, 0.5% Asian American or Pacific Islander, and 1.8% “other races” (as defined by the COMBINE investigators). The mean age of the subsample was 44 years, 70% had at least 12 years of education, and 43% were married. The median annual wage was $35,490 with more than half of participants reporting a gross income greater than $30,000. Retention rate did not differ significantly between treatment conditions. Within treatment, 94% completed all drinking data, while one year post treatment 82.3% provided complete drinking data.

Procedures and Assessment

Upon meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria, participants completed a baseline assessment and were randomly assigned to treatment. Those randomly assigned to the CBI (n=776) had a maximum of 20 treatments sessions available to them over the 16 weeks. Participants were subsequently followed for 52 weeks posttreatment.

CBI was a multiple phase treatment that consisted of motivational interviewing techniques to build client’s motivation for change (Phase 1, typically the first 2 sessions), functional analysis and developing a treatment plan (Phase 2, typically the 3rd through 4th or 5th session), administering CBI modules that were individualized to each client’s situation and needs (Phase 3, typically the 4th or 5th through 16th to 18th session), and maintenance check-ups (Phase 4, typically the final two sessions). Phase 3 treatment procedures were drawn from a menu of nine skills training modules and the selection of modules was based ontherapist’s discretion, the treatment plan, and the therapist’s assessment of the client’s needs and preferences.

The current study focused on the Drink Refusal and Social Pressures module, which was received by 39% of CBI participants (n = 302). The drink refusal module incorporated several components, including the rationale that many clients drink in response to social pressure, an assessment of the social pressures experienced by the client, an assessment of the coping responses most commonly used by the client in response to social pressures, and behavioral rehearsal of coping skills that could be used in social pressure situations. Thirty-five percent of those who received the drink refusal module received it once, 38% received it twice, 18% received the module three times, 6% received the module four times, and 3% received it five or six times.

Measures

A complete list and schedule of all assessments can be found in previous COMBINE publications (Anton et al., 2006). In the current study, data from the Form-90 (Miller & Del Boca, 1994) and the Timeline Follow-Back (Sobell & Sobell, 1995) were used to measure drinking frequency and the Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy scale (AASE; DiClemente et al., 1994) was used as a measure of self-efficacy. Finally, the Working Alliance Inventory – Bond Scale (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) was included as a covariate to measure therapist bond, which has been shown to predict self-efficacy and drinking following treatment in the COMBINE study data (Hartzler, Witkiewitz, Villarroel, & Donovan, 2011)

Drinking outcomes measures

The primary outcome measure used in the current analyses, percent drinking days, was used because the inverse of percent drinking days, percent days abstinent, was one of the primary outcome measures used in the COMBINE study (Anton et al., 2006). In addition, the Drink Refusal Skills training module under investigation in the current analyses should, theoretically, reduce the frequency of drinking by increasing an individual’s ability to refuse offers to drink.

Percent drinking days was defined as the percentage of days, in a thirty day period, when the individual had a drink of alcohol. Percent drinking days was measured during treatment using the Timeline Follow-Back (Sobell & Sobell, 1995) and following treatment using the Form 90 interview (Tonigan et al., 1997). Percent drinking days was square root transformed to reduce the skewness of the variable at each time point. Further, COMBINE drinking reports were biologically verified (Anton et al., 2006).

Self-efficacy

The AASE (DiClemente et al., 1994) was used to measure confidence to abstain from alcohol in high-risk situations (e.g., “When I am being offered a drink in a social situation”) via self-report ratings on a 5-point scale (1=Not at all confident, 5=Extremely confident). The current study utilized all assessments of self-efficacy as measured by the AASE (conducted at baseline, at treatment conclusion, and 10 weeks following treatment). In this sample, confidence subscale scores exhibited excellent internal consistency (average α = 0.97).

The Working Alliance Inventory (WAI)-Bond scale (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989), which was administered during the course of treatment, is a 12-item measure completed by the client to assess a client’s perceptions of alliance with their therapist (e.g., “I believe (therapist) likes me”) on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (always). Internal consistency of the WAI-Bond scale was acceptable (Cronbach α = 0.85).

Data Analytic Plan

Statistical models, described below, were estimated using Mplus version 6.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2010). Considering the complex sampling design in the COMBINE study (participants recruited from 11 sites), all parameters were estimated using a weighted maximum likelihood function and all standard errors were computed using a sandwich estimator1 (the MLR estimator in Mplus). The MLR estimator provides the estimated variance-covariance matrix for the available data and therefore all available data were included in the models. Maximum likelihood is a preferred method for estimation when some data are missing, assuming the data are missing at random (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Attrition analyses revealed no significant differences on any study variables between those with missing data and those with complete data.

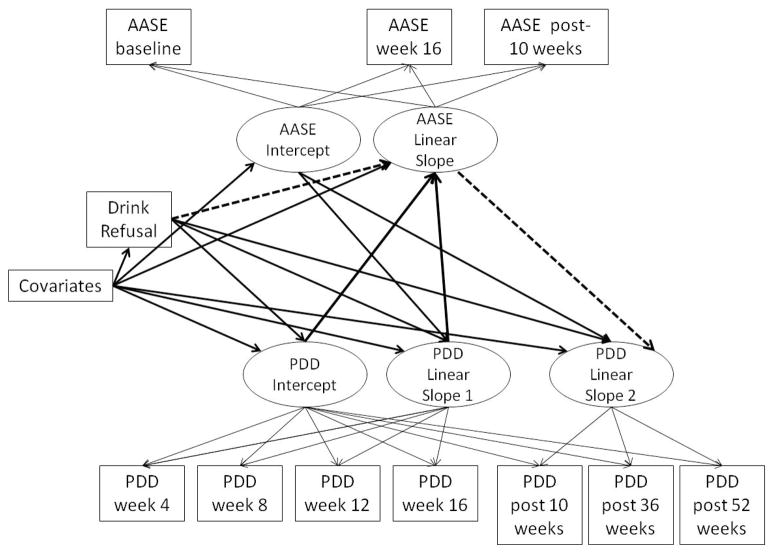

The current study utilized latent growth curve modeling and tests of mediation. Latent growth curve modeling was used to estimate the inter- and intra-individual change in drinking outcomes and self-efficacy over time. The parameters derived from a latent growth model provide information about a construct’s average level (mean intercept) and average change over time (mean slope), as well as the individual variance around the intercept and slope. For the latent growth models we first estimated a series of unconditional models (without covariates) to determine the form of growth (linear, quadratic, nonlinear).2 Mediation models were estimated using the product of coefficients method (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002), which provides an estimate of the mediated (i.e., indirect) effect by multiplying regression coefficients for the regression of the mediator on the independent variable and for the regression of the outcome on the mediator with the independent variable included in the model (MacKinnon, 2008). In the current study we examined mediation within the context of a piecewise parallel process growth model as described by Cheong, Mackinnon & Khoo (2003). As seen in Figure 1 we examined the change in self-efficacy from baseline to the end of treatment (week 16) to 10 weeks following treatment (week 26) as the mediating process and percent drinking days (piece 1: weeks 4–16 during treatment; piece 2: weeks 10–52 following treatment) as the outcome process. The two pieces of the piecewise drinking process model were necessary to separate changes in percent drinking days during treatment from changes in percent drinking days that occurred following treatment. Drink refusal skills training and baseline covariates were included as predictors of both the self-efficacy process and the percent drinking days process. In addition, changes in self-efficacy were regressed on the change in drinking that occurred during treatment.

Figure 1.

Piecewise parallel process mediation model (residual variances and covariances between growth factors not shown in figure, but were estimated in the model). PDD = Percent drinking days; AASE = Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy scale; Covariates included baseline PDD, income, race, and Working Alliance Inventory scores.

Model fit of all models were evaluated by χ2 values, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990). Models with non-significant χ2, RMSEA less than 0.06 and CFI greater than 0.95 were considered a good fit to the observed data (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Models with RMSEA lower than 0.08 and CFI greater than 0.90 were considered an adequate fit to the observed data.

All models were either between groups or within group analyses. The between group analyses compared those who received the drink refusal module (n = 302) to those who did not receive the drink refusal module (n = 474). The within group analyses included only those individuals who received the drink refusal module (n = 302). Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine baseline differences between those who did and did not receive the drink refusal module on demographic (gender, race, income, age, education) and other baseline measures (e.g., family history, alcohol dependence severity, drinking quantity/frequency, readiness to change, drinking related problems, therapeutic alliance, percent of drinkers in the social network, and self-efficacy). Differences between module groups were identified for income and alliance. Individuals who received the module had a higher income (t (763) = −2.82, p = 0.005) and stronger therapeutic alliance (t (614) = −2.25, p = 0.03), and both of these measures were included as covariates in all subsequent analyses. In addition, race (minority group member vs. non-Hispanic white) was included as a covariate because significant effects of race on the association between drink refusal training and drinking outcomes has previously been shown in the COMBINE study data (Witkiewitz, Villarroel, Hartzler, & Donovan, 2011). Specifically, Witkiewitz and colleagues (2011) found that African Americans who received the drink refusal module had better drinking outcomes than non-Hispanic white clients who also received the module.

Results

Descriptive statistics for selected study variables are reported in Table 1. Statistics are provided for all CBI participants, and separately for those CBI participants who did and did not receive the drink refusal module. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to assess the significance of mean differences between drink refusal module groups. As seen in Table 1, individuals who received the drink refusal module had fewer drinking days during treatment and up to one year following treatment. Those who received the drink refusal module also reported significantly greater self-efficacy following treatment.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Mean (Standard Deviation), for Study Variables

| Variable | Total M (SD) | Module not received M (SD) | Module received M (SD) | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDD baseline | 75.29 (26.63) | 75.03 (26.16) | 75.71 (24.82) | 0.00 |

| PDD week 4 of treatment | 24.24 (30.21) | 28.28 (32.61) | 18.00 (24.89)* | 0.36 |

| PDD week 8 of treatment | 26.71 (32.36) | 32.02 (35.31) | 18.99 (25.70)* | 0.42 |

| PDD week 12 of treatment | 25.84 (32.10) | 31.83 (35.19) | 17.23 (24.66)* | 0.49 |

| PDD week 16 (end of treatment) | 26.01 (33.08) | 32.48 (36.29) | 16.74 (25.14)* | 0.50 |

| PDD 10 weeks post-treatment | 31.39 (34.56) | 36.91 (36.61) | 23.50 (29.73)* | 0.40 |

| PDD 36 weeks post-treatment | 37.31 (36.44) | 41.54 (36.80) | 31.21 (35.12)* | 0.29 |

| PDD 1 year post-treatment | 37.61 (37.83) | 41.09 (37.95) | 32.62 (37.15) * | 0.23 |

| AASE baseline | 2.61 (0.74) | 2.64 (0.73) | 2.57 (0.75) | 0.09 |

| AASE end of treatment | 3.54 (0.90) | 3.39 (0.91) | 3.71 (0.86) * | 0.36 |

| AASE 10 weeks post | 3.45 (1.04) | 3.33 (1.05) | 3.59 (0.99) * | 0.25 |

Note. n = 776; PDD = Percent drinking days; DrInC= Drinker Inventory of Consequences; AASE = Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale;

Differences between drink refusal module groups based on independent samples t-test p < 0.05; d = Cohen’s d measure of effect size (small effect = 0.20; medium effect = 0.50; large effect = 0.80).

Effectiveness of the Drink Refusal Module

The first goal of the current study was to examine whether receiving the drink refusal module was associated with better drinking outcomes during CBI and one year following CBI.

Drinking outcomes during treatment

First, latent growth curve modeling was used to examine the changes in percent drinking days during treatment. The model of percent drinking days was based on self-report of drinking over the past 30 days assessed during each month of treatment. Models with linear and quadratic effects with the intercept set at the last assessment point during treatment provided an excellent fit to the observed data (χ2 (6) = 13.37, p = 0.04; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI of RMSEA: 0.01–0.07)). Receiving the module, income, race, and alliance were incorporated into each model as predictors of the growth factors. Results indicated receiving the drink refusal module and therapeutic alliance significantly predicted the intercept (module: β = −0.19; B (SE) = −1.28 (0.24), p < 0.001; alliance: β = −0.09; B (SE) = −0.03 (0.01), p = 0.03), such that individuals who received the module and those who reported a strong alliance with their therapist drank less frequently than those who did not receive the module or reported lower alliance.

Drinking outcomes following treatment

Second, latent growth modeling was used to examine the association between receiving the drink refusal module and each of the covariates in the prediction of percent drinking days up to one year following treatment with assessments at 10-, 36-, and 52-weeks following treatment. Given that only three time-points were available the model was estimated with a linear slope and provided an excellent fit to the data based on CFI and RMSEA. Receiving the drink refusal module was significantly associated with the intercept of percent drinking days (β = −0.15; B (SE) = −1.05 (0.23), p < 0.001). Race was also associated with the intercept of percent drinking days (β = −0.13; B (SE) = −1.14 (0.48), p = 0.02) and income was associated with the intercept of drinking related consequences (β = −0.11; B (SE) = −1.39 (0.49), p = 0.01). No other covariate effects were significant.

Drink Refusal Module and Self-Efficacy

The second goal of the current study was to examine whether changes in self-efficacy were associated with receiving the drink refusal module. First, changes in self-efficacy following treatment were examined by estimating a latent growth model of the AASE from baseline to the last week of treatment and 10 weeks following treatment with the intercept centered at the last week of treatment. The model provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (4) = 14.29, p = 0.01; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.07 (90% CI: 0.03–0.10)). Receiving the drink refusal module significantly predicted level and change in self-efficacy over time, such that receiving the module was associated with higher self-efficacy in the last week of treatment (intercept: β = 0.09; B (SE) = 0.11 (0.05), p = 0.01) and a significant increase in self-efficacy over time (slope: β = 0.16; B (SE) = 0.09 (0.03), p < 0.00). Greater therapeutic alliance and higher income were also significantly associated with a higher level of self-efficacy and higher income was associated a greater increase in self-efficacy over time.

Association between Self-Efficacy and Drinking Following Treatment

Next, a parallel process latent growth curve model was used to examine change in self-efficacy as a predictor of the change in percent drinking days up to one year following treatment. The model provided an excellent fit to the data (χ2 (6) = 5.74, p = 0.45; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI of RMSEA: 0.00–0.05)). The covariances between the intercepts in the model were such that higher self-efficacy was associated with lower percent drinking days (β = −0.72; B (SE) = −2.33 (0.15), p < 0.001). Likewise, change in self-efficacy was significantly associated with the change in percent drinking days (β = 0.26; B (SE) = 0.51 (0.13), p < 0.001) over time.

Mediation Analyses

After establishing a strong association between self-efficacy and drinking outcomes, the third goal of the current study was to examine whether changes in self-efficacy mediated the association between receiving the drink refusal module and drinking outcomes following treatment. Given that the changes in self-efficacy were assessed at the end of treatment and the drinking outcomes were assessed during and following treatment we were interested in testing whether self-efficacy mediated the association between the drink refusal module and drinking outcomes following treatment, while controlling for changes in drinking that were measured during treatment. To accomplish this goal we estimated a piecewise parallel process growth model, shown in Figure 1, of the self-efficacy growth process regressed on receiving the drink refusal module, covariates, and changes in drinking outcomes during treatment (piece 1 of the piecewise model). Then, drinking outcomes following treatment (piece 2 of the piecewise model) were regressed on the self-efficacy growth process, the during treatment growth process, receiving the drinking refusal module, and covariates. In addition, the indirect effect (dashed arrows in Figure 1) of receiving the drink refusal model in predicting the change in percent drinking days following treatment via changes in self-efficacy was estimated. The model was estimated with linear and quadratic effects with the variances of the quadratic effects constrained to zero for model convergence, producing a model with just adequate model fit (χ2 (47) = 332.77, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.08 (90% CI of RMSEA: 0.080–0.098).

Results indicated that the change in self-efficacy was significantly predicted from the intercept and during treatment slope of percent drinking days (intercept: β = −0.51, p < 0.001; during treatment slope: β = −0.55, p < 0.001), with lower percent drinking days and less of an increase in percent drinking days over time associated with a greater increase in self-efficacy over time. Likewise, changes in self-efficacy were significantly associated with changes in drinking following treatment (β = 0.22; B (SE) = 0.65 (0.12), p < 0.001), even after controlling for changes in drinking that occurred during treatment. Consistent with the analyses described above receiving the drink refusal module significantly predicted changes in self-efficacy (β = 0.36; B (SE) = 0.30 (0.10), p = 0.003) and was still a significant predictor of the change in drinking following treatment (β = −0.09; B (SE) = −0.23 (0.11), p = 0.04). In addition, the change in self-efficacy significantly mediated the association between the drink refusal module and the change in percent drinking days following treatment (βindirect = 0.08; B (SE) = 0.20 (0.08), p = 0.01; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.35; proportion mediated = 0.47).

Alternative model of drinking mediating self-efficacy

Given that during treatment drinking intercept and slope predicted the change in self-efficacy, we were interested in whether changes in drinking during treatment potentially mediated the association between receiving the drink refusal module and self-efficacy changes following treatment. To test this hypothesis, a model with drinking changes during treatment as the mediator and self-efficacy changes following treatment as the outcome was estimated. Results indicated that changes in drinking during treatment predicted changes in self-efficacy (β = −0.50; B (SE) = −0.15 (0.02), p < 0.001). However, changes in self-efficacy were still significantly associated with receiving the drink refusal module (β = 0.38; B (SE) = 0.32 (0.11), p = 0.003) and changes in drinking during treatment did not significantly mediate the association between the drink refusal module and changes in self-efficacy (βindirect = 0.06; B (SE) = 0.05 (0.07), p = 0.46; 95% CI: −0.08, 0.18; proportion mediated = 0.14).

Dose-Response

The next set of analyses tested whether there was a dose-response effect whereby receiving the module more times (greater dose) strengthened the response. In order to evaluate the dose-response we estimated the parallel process piecewise mediation models described in the prior section (controlling for during treatment drinking) among only those individuals who received the drink refusal module using within group analyses. Drink refusal dose was included as a predictor of the intercept and slope of self-efficacy scores and drinking outcomes during and following treatment. Drink refusal dose was a significant predictor of the change in self-efficacy (β = 0.18; B (SE) = 0.05 (0.02), p= 0.001) and changes in self-efficacy were associated with changes in percent drinking days (β = −0.72, B(SE) = −1.74 (0.66), p = 0.008). Likewise, changes in self-efficacy significantly mediated the association between the number of times the drink refusal module was received and the growth factors of percent drinking days following treatment (βindirect = 0.13; B (SE) = −0.09 (0.03), p = 0.009; 95% CI: −0.16, −0.02; proportion mediated = 0.68). As seen in Figures 2 and 3, the degree of change in self-efficacy (Figure 2) and changes in percent drinking days across time during and following treatment (Figure 3) was greatest among those who received the module the most times.

Figure 2.

Average self-efficacy change from baseline to the end of treatment (week 16) by how many times the drink refusal module was received.

Figure 3.

Percent drinking days during and following treatment by how many times the drink refusal module was received.

Discussion

The current study examined drinking outcomes following drink refusal skills training as part of a combined behavioral intervention for alcohol dependence. Strong associations were observed between drink refusal training, self-efficacy, and drinking outcomes, such that receiving drink refusal training predicted better drinking outcomes during and following treatment and greater increases in self-efficacy following treatment. Further, changes in self-efficacy partially mediated the association between drink refusal training and drinking outcomes, even when during treatment changes in drinking frequency were incorporated into the model.

Within-subject analyses among those receiving the drink refusal skills training module provided evidence for a dose-response effect, as those receiving the drink refusal training session multiple times evidenced the greatest changes in self-efficacy and greatest changes in drinking. Importantly, results from the piecewise models indicated that changes in drinking during the course of treatment also significantly predicted changes in self-efficacy from baseline to 10 weeks post-treatment. Thus, individuals who were more successful in maintaining abstinence during the course of treatment had greater increases in their belief in their ability to abstain. These increases in self-efficacy were then associated with changes in percent drinking days following treatment. However, the changes in drinking during treatment did not mediate the association between receiving drink refusal training and changes in self-efficacy, thus the change in drinking during treatment could not explain the observed effect of drink refusal training on post-treatment changes in self-efficacy. Unfortunately, it was not possible to test using the COMBINE data whether changes in self-efficacy preceded any changes in drinking or whether changes in drinking entirely preceded changes in self-efficacy. One could also hypothesize that changes in self-efficacy and drinking are bidirectional over time, such that changes in one process feedback into the other process.

The current findings are consistent with the youth prevention literature, which has also found that changes following drink refusal skills training can be partially explained by self-efficacy (e.g., Komro et al., 2001). In addition, learning theories (e.g., classical conditioning) provide a coherent explanation as to why exposure to drink refusal skills training may improve treatment outcomes via enhancement of self-efficacy. Specifically, Bradizza and colleagues (1994) proposed that cognitions (including self-efficacy) are conditioned responses to environmental stimuli and that these cognitions act as conditioned stimuli in eliciting alcohol-related behavioral responses like alcohol-seeking and consumption. Based on this account, the process of rehearsing exposure to high-risk stimuli paired with use and repetition of a drink refusal response may extinguish both the conditioned behavioral response of drinking and cognitions about one’s inability to abstain (e.g., Loeber et al., 2006).

Limitations of the Present Study

Lack of random assignment to the drink refusal module greatly limits our interpretation of the findings and was a significant limitation of the current study. Two approaches were taken to pro-actively address this design limitation. First, all predictors that differentiated those who did and did not receive the module were co-varied in all between group analyses, thus statistically controlling for differences between groups on all available measures. Second, within group analyses among those who received the module were conducted to test whether a greater dose of the drink refusal module predicted greater changes in self-efficacy and better treatment outcomes. Nonetheless, other client characteristics (as well as therapist characteristics) not measured or available from COMBINE study data could have influenced the therapists’ choice of who did and did not receive the drink refusal module or how many times they received the drink refusal module. It is conceivable such characteristics may also explain the differences observed in the current study. Analyses were also limited by the assessments available in the COMBINE dataset. Drinking was assessed during treatment, but self-efficacy was only assessed at the end of treatment. Significant drinking changes were observed within the first month of treatment, before the majority of individuals received drink refusal training and well before the end of treatment assessment of self-efficacy, thus it was not possible to test whether changes in self-efficacy preceded the observed changes in drinking. Several other factors could have influenced changes in both self-efficacy and drinking, such as hopefulness, motivation, and gains in self-understanding (Luborsky, 1995). Furthermore, there were no behavioral assessments of whether drink refusal skills were enacted outside of sessions. In general, we did not have any measures of alcohol-specific coping skills and it is unclear to what extent coping behavior may be associated with self-efficacy and better treatment outcomes. Bradizza and colleagues (2009) found that alcohol specific coping skills significantly mediated the association between a psychosocial intervention and post-treatment alcohol use, but self-efficacy did not mediate the association between coping skills and alcohol treatment outcomes. Consistent with the present study, Bradizza and colleagues (2009) were also unable to examine temporal changes in self-efficacy due to the concurrent measurement of self-efficacy and drinking outcomes. Future research should examine the temporal associations between alcohol use, self-efficacy, and alcohol-specific coping skills (e.g., drink refusal skills) during and immediately following treatment for alcohol dependence.

Conclusions and Future Directions

As noted by Orford (2008), “well-delivered psychological treatments are, in most important respects, the same” (p. 5), and it is critical for psychotherapy research to focus on the processes of change during successful treatments. In recent years the alcohol treatment field has devoted attention to understanding the curative mechanisms of change during and following behavioral treatments for alcohol dependence (Bergmark, 2008; Bradizza et al., 2009; DiClemente, 2007; Longabaugh, Donovan, Karno, McCrady, Morganstern, & Tonigan, 2005; Orford, 2008; Wirtz, 2007). The current study provided support for the notion that drink refusal training, as a specific treatment element of CBI, predicted improved treatment outcomes and greater changes in self-efficacy. Based on the results of the current study, it might be helpful for practitioners to monitor self-efficacy during the course of drink refusal skills training to assess whether the intervention is having an impact on the intended change mechanism. It is important to note that any intervention that increases abstinence self-efficacy may also result in improved alcohol treatment outcomes. Future research could examine whether self-efficacy is a specific mediator of skills training or whether significant changes in abstinence self-efficacy is a general mechanism of change following alcohol treatment.

Future research should be conducted that includes multiple assessments of self-efficacy and drinking during treatment, such data would help determine if there is a temporal ordering (e.g., self-efficacy change precedes drinking change). Ideally, one would conduct an experimental study of self-efficacy as the mechanism of change following specific treatment components by directly manipulating the treatment components received and self-efficacy. Prior studies have shown that self-efficacy can be manipulated by controlling feedback about a person’s performance on a given task (see Cervone et al., 2008; Marquez, Jerome, McAuley, Snook, & Canaklisova, 2002; Shadel & Cervone, 2006). For example, to test the mechanisms proposed in the current study one would need to randomize participants to receive drink refusal training or not and then randomize participants to a drink refusal self-efficacy manipulation. The self-efficacy manipulation would require some sort of task that manipulates efficacy for drink refusal, such as by providing participants with fabricated feedback that they are very likely to refuse a drink (the high self-efficacy condition) or very unlikely to refuse a drink (the low self-efficacy condition). Such a study might not be ethical in an alcohol dependent population, but one could envision such an experiment among non-dependent drinkers. A study of that nature would provide a better understanding of the role of self-efficacy in the association between drink refusal training and drinking behavior.

Footnotes

Given the lack of substantive reasons for differences across sites as well as low intraclass correlations (ICCs) that indicated minimal effects of site (all ICCs below 0.015), we did not use a multilevel modeling framework and instead used a sandwich estimator to adjust the standard errors of model estimates for the minimal influence of treatment site.

There was a substantial decrease in percent drinking days from baseline to the first assessment and the models provided a much better fit to the data when the first assessment of drinking outcomes during treatment was used as the starting point of the growth model with the intercept regressed on baseline drinking. All conditional models were estimated with baseline drinking included in the growth model as the starting point and all models were re-estimated with baseline drinking included as a covariate predictor of the growth model. The substantive findings were the same across models, thus the models with baseline drinking included as a covariate are reported, given they provided a much better fit to the observed data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp

Contributor Information

Katie Witkiewitz, Washington State University.

Dennis M. Donovan, University of Washington.

Bryan Hartzler, University of Washington.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: The COMBINE study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmark A. On treatment mechanisms- what can we learn from the COMBINE study? Addiction. 2008;103:703–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE. The dodo bird is extinct. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bradizza CM, Maisto SA, Vincent PC, Stasiewicz PR, Connors GJ, Mercer ND. Predicting post-treatment-initiation alcohol use among patients with severe mental illness and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1147–1158. doi: 10.1037/a0017320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradizza CM, Stasiewicz PR, Maisto SA. A conditioning reinterpretation of cognitive events in alcohol and drug cue exposure. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1994;25:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burleson JA, Kaminer Y. Self-efficacy as a predictor of treatment outcome in adolescent substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1751–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey LM, Newcombe PA, Oei TP. Cognitive mediation of panic severity: The role of catastrophic misinterpretation of bodily sensations and panic self-efficacy. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:187–200. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervone D, Caldwell TL, Fiori M, Orom H, Shadel WG, Kassel JD, Artistico D. What underlies appraisals? Experimentally testing a knowledge-and-appraisal model of personality architecture among smokers contemplating high-risk situations. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:929–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney EF, O’Leary MR, Marlatt GA. Skill training with alcoholics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:1092–1104. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, Mackinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of meditational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:238. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMBINE Study Research Group. Testing combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence (the COMBINE study): A pilot feasibility study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1123–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000078020.92938.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Carbonari JP, Montgomery RP, Hughes SO. The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:141–148. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC. Mechanisms, determinants and processes of change in the modification of drinking behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(Suppl 10):13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy DW, Nunn LB, Rychtarik RG. Broad spectrum behavioral treatment for chronic alcoholics: Effects of training controlled drinking skills. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:218–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Witkiewitz K, Villarroel N, Donovan DM. Examining therapeutic influences in behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:269–278. doi: 10.1037/a0022869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Delucchi KL, Hall SM. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersen M, Bellack AS. Assessment of social skills. In: Ciminero AR, Calhoun KS, Adams HE, editors. Handbook for Behavioral Assessment. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research. 2009;19:418–428. doi: 10.1080/10503300802448899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Perry CL, Williams CL, Stigler MH, Farbakhsh K, Veblen-Mortenson S. How did Project Northland reduce alcohol use among young adolescents? Analysis of mediating variables. Health Education Research. 2001;16:59–70. doi: 10.1093/her/16.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Coping skills training and contingency management treatments for marijuana dependence: Exploring mechanisms of behavior change. Addiction. 2008;103:638–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Stephens RS. Coping and self-efficacy in marijuana treatment: Results from the Marijuana Treatment Project. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1015–1025. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber S, Croissant B, Heinz A, Mann K, Flor H. Cue exposure in the treatment of alcohol dependence: Effects on drinking outcome, craving, and self-efficacy. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;45:515–529. doi: 10.1348/014466505X82586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Donovan DM, Karno MP, McCrady BS, Morganstern J, Tonigan JS. Active ingredients: How and why evidence-based alcohol behavioral treatment interventions work. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:235–247. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153541.78005.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L. The first trial of the P technique in psychotherapy research—a still-lively legacy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, Jerome GJ, McAuley E, Snook EM, Canaklisova S. Self-efficacy manipulation and state anxiety responses to exercise in low active women. Psychology & Health. 2002;17:783–791. [Google Scholar]

- Mensinger JL, Lynch KG, Tenhave TR, McKay JR. Mediators of telephone-based continuing care for alcohol and cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:775–784. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 1994;12:112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Kadden RM, Rohsenow DJ, Cooney NL, Abrams DB. Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. (Version 6.1) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary DE, O’Leary ME, Donovan BM. Social skill acquisition and psychosocial development of alcoholics: A review. Addictive Behaviors. 1976;1:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Oei TPS, Hasking PA, Philips L. A comparison of general self-efficacy and drinking refusal self-efficacy in predicting drinking behavior. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:833–841. doi: 10.1080/00952990701653818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J. Asking the right questions in the right way: The need for a shift in research on psychological treatments for addiction. Addiction. 2008;103:875–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig S. Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1936;6:412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Cole KC, Fang L. Gender-specific intervention to reduce underage drinking among early adolescent girls: A test of a computer-mediated, mother-daughter program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:70–77. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR, Levin M, Bryan AD. Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:38–50. doi: 10.1037/a0014513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Cervone D. Evaluating social cognitive mechanisms that regulate self-efficacy in response to provocative smoking cues: An experimental investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:91–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, McCrady BS. Cognitive impairment among alcoholics: Impact on drink refuasl a skill acquisition and treatment outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16:265–274. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90019-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Controlled drinking after 25 years: How important was the great debate? Addiction. 1995;90:1157–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate SR, Wu J, McQuaid JR, Cummins K, Shriver C, Krenek M, Brown SA. Comorbidity of substance dependence and depression: Role of life stress and self-efficacy in sustaining abstinence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:47–57. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Brown JM. The reliability of Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(4):358–366. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE. The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stich F, Benson K, Ahn H. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “All must have prizes. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz PW. Advances in causal chain development and testing in alcohol research: Mediation, suppression, moderation, mediated moderation, and moderated mediation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(Suppl 10):57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Villarroel NA, Hartzler B, Donovan DM. Drinking outcomes following drink refusal skills training: Differential effects for African American and non-Hispanic White clients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:162–167. doi: 10.1037/a0022254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]