Abstract

An immature intestinal epithelial barrier may predispose infants and children to many intestinal inflammatory diseases, such as infectious enteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and necrotizing enterocolitis. Understanding the factors that regulate gut barrier maturation may yield insight into strategies to prevent these intestinal diseases. The claudin family of tight junction proteins plays an important role in regulating epithelial paracellular permeability. Previous reports demonstrate that rodent intestinal barrier function matures during the first 3 weeks of life. We show that murine paracellular permeability markedly decreases during postnatal maturation, with the most significant change occurring between 2 and 3 weeks. Here we report for the first time that commensal bacterial colonization induces intestinal barrier function maturation by promoting claudin 3 expression. Neonatal mice raised on antibiotics or lacking the toll-like receptor adaptor protein MyD88 exhibit impaired barrier function and decreased claudin 3 expression. Furthermore, enteral administration of either live or heat-killed preparations of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG accelerates intestinal barrier maturation and induces claudin 3 expression. However, live Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG increases mortality. Taken together, these results support a vital role for intestinal flora in the maturation of intestinal barrier function. Probiotics may prevent intestinal inflammatory diseases by regulating intestinal tight junction protein expression and barrier function. The use of heat-killed probiotics may provide therapeutic benefit while minimizing adverse effects.

Impaired or immature barrier function plays a key role in the pathogenesis of many intestinal inflammatory diseases of newborns and children, such as idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),1,2 infectious enteritis, or necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).3–6 Tight junctions (TJs) maintain separation of tissue compartments by sealing the intercellular space while regulating paracellular permeability.7,8 During early postnatal maturation, the intestinal barrier tightens and becomes more selectively permeable in both premature neonates9,10 and neonatal animal models.11–14 Although dietary and trophic factors, such as epidermal growth factor,15 and hormonal factors, such as endogenous glucocorticoids,16 are involved with postnatal intestinal maturation, other factors are likely to play an important role in regulating barrier tightening in the immature gut. Commensal bacteria, which normally colonize the murine gut during the first several weeks of postnatal life,17 induce expression of genes that improve intestinal barrier function, whereas abnormal bacterial colonization may disrupt this process and contribute to the development of host diseases.18 Neonates with abnormal intestinal microbial composition may be predisposed to NEC, IBD, or infectious enteritis as the result of a failure in postnatal maturation of this critical protective barrier. The immature neonatal intestinal barrier may fail to prevent systemic entry of microbes or microbial products and other toxins from within the gut lumen, leading to intestinal inflammation and injury.10,19–21 Indeed, preterm infants with altered intestinal flora due to prolonged antibiotic therapy are more likely to develop NEC,22,23 and abnormal bacterial colonization is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD.1 Furthermore, probiotics composed of commensal bacteria have shown promise in reducing the incidence and severity of NEC,4 IBD,24 and infectious diarrhea25 in infants and children.

Commensal bacterial signaling through toll-like receptors (TLRs) is vital in maintaining the intestinal barrier.26 In addition, alterations in TJ protein expression have contributed to impaired barrier function in both IBD27 and rodent models of NEC.28,29 To determine how acquisition of commensal flora in the preterm infant may influence the ontogeny of intestinal barrier function, as regulated by TJ proteins, we modeled preterm human intestinal epithelia using the neonatal mouse. Neonatal murine intestinal epithelia are relatively immature at birth when compared with term human epithelia, and murine intestinal epithelia at 2 weeks postnatally resemble that of a human at 24 gestational age.30 In addition, the murine gut acquires its complement of flora, beginning at approximately 2 weeks postnatal age.17 Consistent with previous developmental studies13,31 in rodents, we demonstrate that the tightness of the intestinal epithelial barrier, as measured by decreased paracellular permeability, matures over time, with the most significant change occurring at 3 weeks of life.

Claudins, a key component of TJs, demonstrate striking changes in postnatal expression and localization.32 Here we report for the first time that intestinal barrier function and intestinal expression and localization of claudin 3 may be regulated by signaling from gut flora. Mature expression and localization of claudin 3 occurs at 3 weeks in the postnatal mouse, coincident with maturation in gut permeability. MyD88 null and antibiotic-raised mice both demonstrate impairment in barrier function with deficient expression of claudin 3. Finally, we report that maturation of both gut barrier function and claudin 3 expression can be induced by probiotic administration. Neonatal mice gavage fed Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) exhibit increased claudin 3 expression and a dose-dependent acceleration of postnatal barrier maturation. In addition, heat-killed LGG is able to preserve the therapeutic effect of high-dose LGG while reducing associated mortality. These results indicate that intestinal barrier function, as regulated by TJ protein expression, can be influenced by gut flora. Probiotics may act to prevent intestinal diseases in neonates and children by improving intestinal barrier function through induction of appropriate TJ protein expression and localization.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University (Atlanta, GA). C57BL/6J mice were bred in an animal facility at Emory University. MyD88−/− mice, originally generated by Shizuo Akira (Osaka, Japan), were extensively backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background, as previously described.33 Tissue samples were harvested at various time points, ranging from embryonic day (E) 18 using timed-pregnant mice to adult (aged 8 weeks). Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation or decapitation after CO2 anesthesia. The distal third of the small intestine was immediately frozen for protein assays, placed in RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), or frozen in Tissue-Tek Optimal Cutting Temperature medium (Sakura, Torrance, CA) for histological staining.

Antibiotic Treatment

To prevent bacterial colonization of neonatal mice, adult males and females were separated and treated for 3 weeks with neomycin (1 g/L), vancomycin (0.5 g/L), ampicillin (1 g/L), and metronidazole (1g/L) in drinking water to deplete commensal flora, as previously described.26 Kool-Aid Mix (20 mg/mL) (Kraft Foods, Glenview, IL) was added to drinking water to promote consumption, as previously described.34 Antibiotic solution was passed through a 0.45 μmol/L sterile filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and replaced two to three times per week. After 3 weeks, male and female mice were combined for mating and antibiotic water was continued. Cecal images were obtained and compared between antibiotic-treated and control mice as a marker for prevention of bacterial colonization (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), because cecal enlargement is characteristic of germ-free mice.35 Enlargement of the cecum is attributed to hydrotropic mucus and retention of water, which is a consequence of the absence of mucolytic bacteria.30

LGG Experiments

LGG (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was prepared in overnight culture, as previously described,36,37 then washed and concentrated in PBS. Mice were gavage fed PBS, with or without LGG [1 × 107 to 1 × 109 colony-forming units (CFU) per day], in an equal volume daily for 7 days beginning at the age of 1 week. Heat-killed LGG was prepared by exposing the concentrated LGG culture (1 × 109 CFU) to 70°C for 30 minutes. Heat-killed samples were examined by plating on MRS media (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) under anaerobic conditions and direct visualization by light microscopy to confirm nonviability without disruption of cell wall architecture. To visualize fluorescent LGG within prepared sections of the neonatal distal small intestine by confocal microscopy, the bacterium was stained with the fluorescent amine-reactive dye Cell Trace Far Red DDAO-SE (catalog #C34553, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, an overnight culture of LGG, grown in liquid MRS media, was washed twice and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS at a concentration of 1 × 109 CFU/mL. The DDAO-SE dye was resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide, and 12.5 μg was added to the washed and resuspended LGG. After oral gavage administration of LGG at a concentration of 1 × 109 CFU, the distal small intestine was harvested and frozen in OCT. Frozen tissue sections (8 μm thick) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100. Tissue sections were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (A12379; Invitrogen). Immunofluorescent localization was evaluated by confocal microscopy (model LSM510; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Claudin Histological Staining

Frozen tissue sections (6 μm thick) of distal small intestine were fixed in 100% ethanol at −20°C for 20 minutes. Sections were stained with primary rabbit anti-claudin 3 (34-1700, Invitrogen) at a 1:500 dilution for 1 hour, followed by secondary anti-rabbit IgG (488 nm) at 1:500 (A11008; Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO (T3605; Invitrogen) for 2.5 minutes. Immunofluorescent localization was evaluated by confocal microscopy (model LSM510; Zeiss).

Intestinal Permeability Assays

Barrier function was evaluated by measuring in vivo paracellular permeability to fluorescent-labeled dextran, as previously described.38 Briefly, mice were fasted for 4.5 hours and then gavage fed 22 μL/g of 22 μg/μL fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled 4.4-kDa dextran (FD4; Sigma, St Louis, MO). Serum was obtained 1 to 5 hours after gavage administration by terminal cardiac puncture (mice aged ≥2 weeks) or decapitation (mice aged 1 week) after CO2 anesthesia. The serum FD4 concentration was calculated by comparing samples with serial dilutions of known standards using Synergy HT fluorimeter (BioTek, Winooski, VT) with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm. A gain of 50 was used for all experiments.

Western Blot/Protein Analysis

Intestinal tissue was prepared for Western blot analysis in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer, as previously described.36 Samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose by electroblotting. Membranes were probed with primary anti-occludin (71–1500; Invitrogen), anti-claudin 3 (34–1700; Invitrogen), and anti-claudin 7 (34–9100; Invitrogen) at 1:500 and secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)–horseradish peroxidase (G21234; Invitrogen) at 1:1000. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were loaded in each lane, as determined by the Bradford protein assay. Band densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and normalized to occludin expression.

Evaluation of mRNA Expression

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with on-column DNase digestion using the RNAase-Free DNase set (Qiagen), per manufacturer's protocols. All RNA had A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios between 1.8 and 2.2. Reverse transcription was performed with 0.5 μg RNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Two-step quantitative real-time PCRs were performed in duplicate for the developmental survey of TJ protein expression and in triplicate for all other assays, with normalization to 18s using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). Gene expression was compared between samples by using the 2−ΔΔCT method.39 Primers were designed using Beacon Design software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and OligoAnalyzer (IDT Technologies, Coralville, IA). Full primer sequences are available by request.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t-tests (two groups) or an analysis of variance with a post hoc Tukey's multiple-comparison test (more than two groups) was used where appropriate. In instances in which data demonstrated a nongaussian distribution, a Mann-Whitney U-test (two groups) or a Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn's multiple-comparison test (more than two groups) was used where appropriate. A log-rank Mantel-Cox test was used to compare survival. Prism Version 5 for Windows (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) was used for all statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Bars depict mean values, with error bars representing a single measure (SEM).

Results

Murine Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Tightens by 3 Weeks Postnatal Age

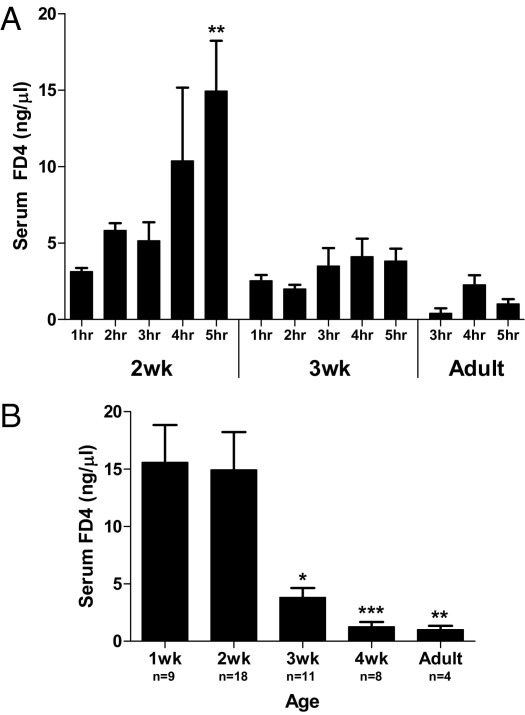

Intestinal epithelial barrier function develops postnatally in the neonatal mouse, with the 2-week-old mouse demonstrating similar intestinal epithelial maturity as a 24-week gestational age human.30 Thus, the neonatal murine gut is often used to model premature human intestines.36,37,40–42 To characterize the ontogeny of gut barrier function, we measured in vivo intestinal permeability to 4.4kDa dextran FD4 in the neonatal mouse during the first 8 weeks of life. FD4 is a selective marker for paracellular permeability and has been used to evaluate both intestinal permeability19 and TJ function.43 First, to optimize our assay for age-related differences in intestinal transit time, we measured serum FD4 dextran concentrations 1 to 5 hours after oral gavage administration (Figure 1A). Serum FD4 dextran peaked at 5 hours after gavage in 2-week-old mice, at 3 to 5 hours in 3-week-old mice, and at 4 hours in adult mice. Thus, all further studies evaluating the development of intestinal epithelial barrier function and paracellular permeability were assayed in mice 5 hours after gavage administration of FD4. Consistent with the idea that the 3-week-old mouse intestine resembles the maturity of a term human intestine, we found significant maturation in gut barrier function (as measured by a fourfold decline in intestinal permeability to FD4 dextran) between 2 and 3 weeks (serum FD4 dextran, 14.9±3.3 and 3.8±0.8, respectively; P < 0.01), with continued decline thereafter (Figure 1B). These results indicate that the critical period for maturation of gut barrier function occurs between 2 and 3 weeks of postnatal life in the neonatal mouse and that 2-week-old mice may be used to study the role of immature barrier function in premature intestinal diseases, such as NEC.

Figure 1.

Murine intestinal epithelial barrier tightens by 3 weeks of postnatal age. A: Time course of intestinal permeability as determined by serum FD4 concentration measured 1 to 5 hours after oral gavage in mice at the ages of 2 and 3 weeks and in adult mice. Data are the mean ± SEM from at least three experimental repeats per condition. **P < 0.01 versus the 1-hour time point. B: Ontogeny of intestinal permeability, as measured by serum FD4 concentration measured 5 hours after gavage administration during the first 8 weeks of life. Data are the mean ± SEM from at least three experimental repeats per condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus the 2-week time point.

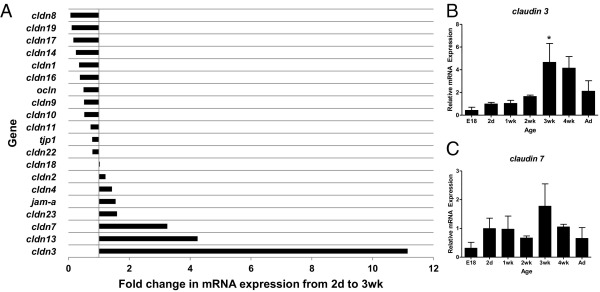

Claudin 3 Gene Expression Peaks at 3 Weeks in the Murine Intestine

Alterations in TJ protein expression contribute to impaired barrier function in both IBD27 and rodent models of NEC.28 To identify candidate TJ proteins that may play a key role in maturation of intestinal barrier function, we initially quantified intestinal mRNA expression of a panel of TJ proteins during the first 8 weeks of murine life. Several TJ proteins, including claudins 3, 7, and 13, demonstrated 3- to 11-fold increases in mRNA expression from 2 days to 3 weeks of age (Figure 2A). Based on these findings, we chose to further characterize the developmental mRNA and protein expression of claudins 3 and 7, because they may play a role in tightening of epithelial barriers.44,45 We demonstrate that both claudin 3 and 7 mRNA expression peaked at 3 weeks of postnatal age (Figure 2, B and C), the same age at which intestinal permeability in the developing postnatal gut significantly decreased (Figure 1A). However, the developmental increase in claudin 7 mRNA expression was more variable. These results indicate that claudins 3 and 7 may play a key role in the postnatal maturation of murine intestinal barrier function.

Figure 2.

Claudin 3 gene expression peaks at 3 weeks in the murine intestine. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR of TJ protein genes undergoing developmental changes in expression in murine intestines collected during the first 8 weeks of life. A: Developmental survey of TJ protein gene expression. Bars represent fold induction when comparing mRNA levels in 3-week-old versus 2-day-old mice. B and C: mRNA expression of claudin 3 (B) and claudin 7 (C) over time. Data are expressed as fold change (mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments) versus 2 days old (set to 1).

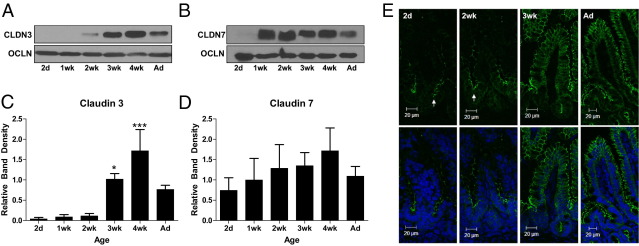

Mature Claudin 3 Protein Expression and Localization Occurs at 3 Weeks in the Murine Gut

To further evaluate the potential relevance of these two candidate TJ proteins to maturation of intestinal barrier function in the 3-week-old mouse, we measured the expression of intestinal claudins 3 and 7 by immunoblot analysis. Protein levels of claudin 3 (Figure 3, A and C) demonstrate dramatic increases beginning at 3 weeks postnatal age, whereas expression of occludin, another tetraspan TJ protein, remains relatively constant throughout postnatal development (Figure 3, A and B). In contrast, protein levels of claudin 7 (Figure 3, B and D) demonstrate no significant developmental changes. Based on the significant increase in claudin 3 expression at 3 weeks postnatal age, we hypothesized that claudin 3 was a potential mediator of postnatal decreases in paracellular permeability seen at 3 weeks of age and selected this candidate TJ protein for further study.

Figure 3.

Mature claudin 3 protein expression and localization occurs at 3 weeks in the murine gut. A and B: Developmental expression of claudin 3 (CLDN3; A), CLDN7 (B), and occludin (OCLN) protein by using Western blot analysis in murine intestines collected during the first 8 weeks of life. Ad, adult. C and D: Band densitometry analysis of CLDN 3 (C) and CLDN 7 (D) protein expression, with protein density referenced to OCLN and normalized to 2 days postnatal age. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 versus the 2-day time point. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. E: Immunofluorescent localization of claudin 3 in 2-day-old, 2-week-old, 3-week-old, and Ad mice. Top panels: claudin 3 staining alone (green). Bottom panels: Nuclear counterstain (blue). Immature localization is noted primarily along the crypts in 2-day-old and 2-week-old mice (arrows). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Next, we characterized intestinal claudin 3 localization by immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy during the first 8 weeks of murine life (Figure 3E). Coincident with increases in both mRNA expression and protein levels, claudin 3 demonstrates mature protein localization at 3 weeks postnatal age, with similar localization as adult mice. Claudin 3 remained localized in the TJs of crypt epithelium in younger mice (2 days and 2 week) and transitioned to additional expression in the mature villous epithelial cells beginning at the age of 3 weeks. These results suggest that appropriate localization and protein levels of claudin 3 may play a key role in maturation of the intestinal barrier in the developing neonatal mouse.

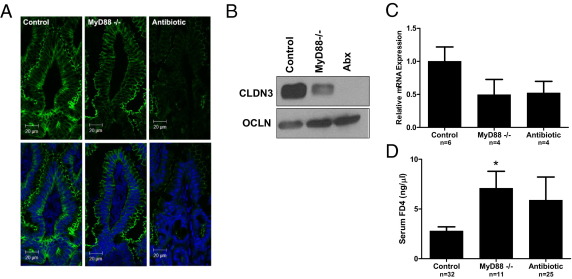

Maturation of Intestinal Claudin 3 Expression and Barrier Function Is MyD88 Dependent

Commensal bacterial signaling through TLRs is vital in maintaining the intestinal barrier.26 Mice with significantly reduced intestinal commensal bacteria (mice treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics) and mice lacking a key adaptor molecule for TLR signaling (MyD88−/− mice) exhibit exaggerated responses to intestinal injury.26 Furthermore, studies46 indicate that TLR signaling, specifically through TLR-2, may play a key role in TJ protein expression and epithelial barrier maturation and protect against TJ disruption in murine colitis. To determine whether acquisition of gut flora, occurring during the first several weeks of murine life,17 induces expression of claudin 3 through microbial interaction with TLRs, we compared protein expression of claudin 3 in wild-type conventionally reared mice (control) with MyD88−/− and antibiotic-raised wild-type mice at 3 weeks of life. Three-week-old MyD88−/− and antibiotic-raised wild-type mice exhibit decreased and immature expression of claudin 3, with attenuated immunofluorescent staining in the TJs of surface epithelial cells (Figure 4A). In addition, decreased claudin 3 protein levels were observed by using Western blot analysis (Figure 4B). The immature expression of claudin 3 appears to be transcriptionally regulated with decreased mRNA expression (Figure 4C) noted in MyD88−/− and antibiotic-raised mice at 3 weeks of life compared with control mice. More important, MyD88−/− and antibiotic-raised mice also demonstrate immature barrier function compared with control mice with significantly increased FD4 intestinal permeability seen in MyD88−/− mice (Figure 4D). The trend toward increased permeability in antibiotic-raised mice was associated with increased variability in this group. These results indicate that MyD88-dependent TLR signaling by commensal bacteria may play a key role in the maturation of neonatal murine intestinal barrier function through induction of claudin 3 expression.

Figure 4.

Maturation of intestinal claudin 3 expression and barrier function is MyD88 dependent. A: Immunofluorescent localization of claudin 3 in wild-type (control), MyD88−/−, or antibiotic-raised (Abx) 3-week-old mice. Top panels: claudin 3 staining alone (green). Bottom panels: Nuclear counterstain (blue). B: Expression of CLDN3 and occludin (OCLN) protein by immunoblot in murine intestines at the age of 3 weeks. C: Relative intestinal mRNA expression of claudin 3 in wild-type (control), MyD88−/−, or antibiotic-raised 3-week-old mice, as assayed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Data are the mean ± SEM from at least three experimental repeats per condition. D: Intestinal permeability, as measured by serum FD4 concentration 5 hours after oral gavage in wild-type (control), MyD88−/−, or antibiotic-raised 3-week-old mice. Data are the mean ± SEM from at least three experimental repeats per condition. *P < 0.05 versus control.

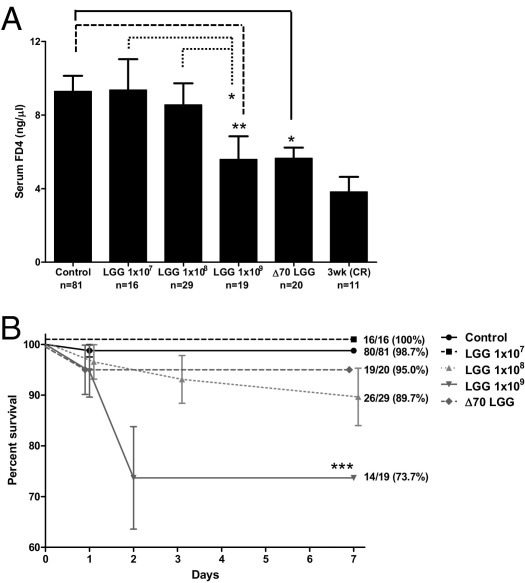

LGG Accelerates Barrier Maturation by Induction of Claudin 3

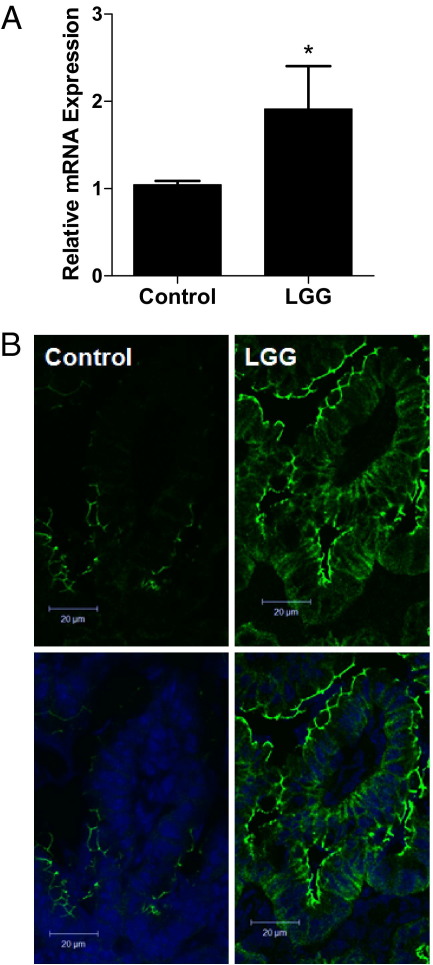

Delayed or inappropriate intestinal bacterial colonization has been implicated in the pathogenesis of NEC22,47 and IBD.1 Probiotics containing commensal bacterial species, such as Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium, have reduced the incidence and severity of NEC.4 Probiotic administration may act by normalizing microbial populations or by directly improving host defense mechanisms. Specifically, probiotics containing commensal bacteria may strengthen intestinal barrier function, which, in turn, may reduce systemic entry of gut luminal microbes or toxins. Our group has previously demonstrated that the probiotic LGG augments host intestinal defense by promoting cytoprotective gene expression.37 To determine whether LGG can similarly improve epithelial barrier function in the immature murine gut, we compared intestinal claudin 3 expression and barrier function in 2-week-old mice pretreated with enterally administered live LGG, heat-killed LGG, or carrier control. Two-week-old mice gavage fed live or heat-killed LGG at 1 × 109 CFU/day (for 1 week) demonstrated significantly improved barrier function with decreased intestinal paracellular permeability when compared with those treated with lower doses or carrier control (Figure 5A). In addition, 2-week-old mice treated with high-dose LGG (live or heat killed) exhibited intestinal permeability similar to that of 3-week-old conventionally reared controls, suggesting that early probiotic administration can accelerate developmental barrier maturation. Furthermore, although treatment with live high-dose LGG (1 × 109 CFU) was associated with increased mortality, high-dose heat-killed treatment was not (Figure 5B). Finally, LGG treatment (1 × 109 CFU) resulted in a twofold induction of claudin 3 intestinal mRNA expression (Figure 6A) and increased expression of claudin 3 by immunofluorescent microscopy (Figure 6B), suggesting that claudin 3 may play a pivotal role in probiotic-induced barrier maturation. In addition, we provide a potential mechanism by which LGG is able to reduce intestinal permeability.

Figure 5.

LGG accelerates barrier maturation. A: Intestinal permeability in 2-week-old mice, as measured by serum FD4 concentration (5 hours after oral gavage) in mice fed PBS alone (control) or with live (1 × 107 to 1 × 109 CFU) or heat-killed (1 × 109 CFU) LGG for 1 week. Intestinal permeability was compared with 3-week-old conventionally raised (CR) mice as a reference point for mature intestinal barrier function. Data are the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. B: Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the same experimental groups as described in A. The percentage survival and the number of mice per group are indicated. ***P < 0.001 by log-rank Mantel-Cox test.

Figure 6.

LGG induces claudin 3 expression. A: Relative intestinal mRNA expression of claudin 3, as assayed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR in mice gavage fed PBS alone (control) or with LGG for 1 week. Intestines were harvested at the age of 2 weeks. Data are the mean ± SEM from at least three experimental repeats per condition. *P < 0.05 versus control. B: Immunofluorescent localization of claudin 3 in mice treated with PBS alone (control) or with LGG (1 × 109 CFU) for 1 week. Top panels: claudin staining alone (green). Bottom panels: Nuclear counterstain (blue).

Discussion

Impaired intestinal barrier function has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many intestinal inflammatory syndromes, such as infectious enteritis, IBD,1,2 and NEC.3,4,48,49 Thus, investigations aimed at understanding the mechanisms behind the postnatal maturation of intestinal barrier function are critical to developing preventative clinical strategies to reduce the incidence or severity of these devastating diseases. Commensal bacteria up-regulate expression of genes that control intestinal barrier function.18 In this study, we show that the gene expression of multiple intestinal epithelial TJ proteins is developmentally regulated, with key changes occurring at 2 to 3 weeks of life and coincident with the acquisition of enteric flora in neonatal mice.17

Developmentally deficient TJ protein expression may contribute to the barrier dysfunction that predisposes to intestinal inflammatory diseases seen in preterm newborns. In this study, the developmental survey of TJ proteins implicated claudin 3 as the most transcriptionally up-regulated TJ protein during an important period of postnatal development. The maturation of claudin 3 protein expression and localization in murine intestinal epithelia occurred simultaneously with maturation of intestinal epithelial barrier function at 3 weeks postnatal age.

We were particularly interested in exploring the role of claudin 3 in developmental maturation of barrier function because it is an important tightening claudin that is highly expressed in the mature adult intestine,50,51 although its role in the developing intestine remains unclear. Claudin 3 expression is also altered in experimental NEC,28 and loss of intestinal claudin 3 with urinary detection is associated with intestinal injury in humans and rodents52 and can be used as a biomarker for early diagnosis and determination of the severity of NEC in premature neonates.53 Previous reports28,29 demonstrate increased intestinal claudin 3 in a rodent model of experimental NEC. However, whether increased intestinal claudin 3 occurs as a response to intestinal injury or predisposes to intestinal injury has not been clear. Our data strongly support the role of claudin 3 as a tightening TJ protein that aids in sealing of the paracellular intestinal barrier, and impaired expression may play a role in predisposition to intestinal disease. Thus, we suspect that increased intestinal claudin 3 expression may be an attempt by the host to repair the epithelial barrier during intestinal injury. The transition of claudin 3 localization from the crypt to villus, occurring at 3 weeks postnatal age, may be critical in establishing a more selective paracellular barrier. Coupled with this transition is increased basolateral expression of claudin 3, although the specific role of basolateral expression of select claudins remains unclear. Potential functions of basolaterally expressed claudins include serving as a pool for functional claudins as TJs undergo assembly and disassembly and involvement in cell signaling.54,55

Because MyD88−/− and antibiotic-raised mice demonstrate increased intestinal permeability and reduced claudin 3 expression at 3 weeks of life compared with wild-type mice, commensal bacteria may play a key role in the developmental regulation of intestinal barrier function. Although antibiotic-raised mice demonstrated a trend toward increased permeability, variability in gut barrier function in this group may be the result of host-specific changes in intestinal flora. Prior studies56 have demonstrated that altering the normal commensal colonization of rat pups by the administration of antibiotics to pregnant rats alter both postnatal intestinal growth and barrier properties.

We suspect that TLR interaction with bacterial ligands may play a significant role in claudin 3–dependent barrier maturation. However, the signaling pathways linking TLR activation and claudin 3 expression in the developing intestine remain poorly understood and are an area for future study. Interestingly, maturation of intestinal permeability (3 weeks) seems to occur approximately 1 week after acquisition of commensal flora (2 weeks) in the mouse. Similarly, increased barrier function in response to the probiotic LGG occurred after 1 week of treatment in our studies. These data suggest that the use of probiotics clinically to modulate intestinal barrier function may be most effective in preventing, rather than treating, disease.

Probiotics remain a promising therapy in intestinal diseases, particularly those that affect the immature epithelia of preterm human intestines. Given that an immature intestinal barrier likely plays a role in the pathogenesis of NEC,57,58 probiotics may restore or replace essential strains of commensal flora necessary for barrier maturation in a preterm gut that is impaired by delayed commensal colonization and low bacterial diversity.59 Lactobacillus species specifically appear to be a critically sensitive commensal that is lacking in preterm infants and is also more susceptible to eradication in response to antibiotic treatment and stress.59 Lactobacillus species have reduced Rotaviral-induced increases in intestinal permeability in immature suckling rats,60 and previous groups have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of both live36 and heat-killed LGG on reducing inflammation in immature epithelia.61 In our study, up-regulation of claudin 3 expression by LGG treatment was associated with acceleration in the developmental maturation of the intestinal barrier. Whether probiotic-induced up-regulation of claudin 3 expression and barrier maturation can reduce or prevent infectious enteritis, NEC, or IBD experimentally remains an area of future investigation. Although results from both human trials and experimental animal models have generated encouraging data regarding the beneficial effects of probiotics in reducing NEC incidence and severity, the widespread use of probiotic therapy is limited by concerns regarding adverse effects, such as sepsis.62,63 These concerns parallel our findings in which mice treated with high-dose LGG demonstrate significantly increased mortality. The risks of administration of live bacteria to an intestine with an immature epithelial barrier are particularly relevant in our study. We demonstrated increased mortality when 1-week-old mice were treated with live high-dose LGG (1 × 109 CFU/day for 7 days). Our data indicate that mice <3 weeks old have a leaky intestinal paracellular barrier. This immature neonatal intestinal epithelial barrier may be permeable to bacteria or bacterial products, which, in turn, may cause increased morbidity and mortality if bacteria penetrate the epithelial barrier. Supporting this idea, we gavage fed 2-week-old mice with fluorescently labeled LGG, and demonstrated multiple bacteria crossing the intestinal epithelial barrier into the lamina propria (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Similar concerns regarding appropriate dosing of probiotic strains are highlighted in a recent study,64 in which preterm piglets treated with high doses of live probiotic strains developed a higher incidence of NEC. Promisingly, we recapitulated the positive effect of live high-dose LGG with heat-killed LGG while avoiding the associated mortality. This supports the therapeutic use of either purified or nonviable bacterial products that may replicate the beneficial effects of live probiotics without the associated risks.

In conclusion, these data provide evidence that commensal and probiotic bacteria play a key role in the developmental maturation of the intestinal barrier by regulating claudin 3 protein expression. More important, our data indicate that probiotic administration can accelerate the maturation of both claudin 3 protein expression and intestinal barrier function in an immature gut lacking commensal bacteria. Thus, one mechanism by which probiotics may prevent intestinal diseases affecting neonates and children is by inducing maturation of claudin 3 protein-regulated intestinal epithelial permeability. Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of exercising caution when considering the therapeutic use of live probiotics in hosts with immature or compromised barrier function. Heat-killed probiotics may be a promising alternative to live bacteria as a therapy with significantly less risk for adverse outcomes. Future studies aimed at investigating the signaling pathways stimulated by probiotic bacteria that can regulate intestinal TJ protein expression and barrier function may aid in the development of targeted therapies to prevent or reduce the severity of infant and childhood intestinal inflammatory syndromes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Neish for critical review of the manuscript and Jeff Mercante for the preparation of fluorescently labeled LGG.

Footnotes

Supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DK007771 from the NIH (R.M.P.), grants from the NIH (R01 HD059142 and HD059142-01S1 to A.M.; R01 DK 059888 to A.N.; and R01 HD059122 to P.W.L.), and a grant from the Emory Digestive Diseases Research Development Center (R24 DK064399).

CME Disclosure: None of the authors disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.025.

Current address of A.M., Department of Pediatrics, University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Supplementary data

Cecal enlargement in antibiotic-treated mice. Cecal enlargement demonstrated in antibiotic-treated (Abx) mice versus wild-type (WT) controls at the age of 3 weeks.

LGG crosses the immature intestinal epithelial barrier of 2-week-old mice. Representative confocal images from 2-week-old mice fed fluorescently labeled LGG (red), demonstrating bacteria (arrows) in the lumen (A) and lamina propria (B) of distal small-intestinal sections. Epithelia were labeled with anti-phalloidin (green).

References

- 1.Sartor R.B. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayburgh D.R., Shen L., Turner J.R. A porous defense: the leaky epithelial barrier in intestinal disease. Lab Invest. 2004;84:282–291. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grave G.D., Nelson S.A., Walker W.A., Moss R.L., Dvorak B., Hamilton F.A., Higgins R., Raju T.N. New therapies and preventive approaches for necrotizing enterocolitis: report of a research planning workshop. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:510–514. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318142580a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfaleh K., Bassler D. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub2. CD005496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry M.C., Moss R.L. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:98–109. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon P.V., Swanson J.R., Attridge J.T., Clark R. Emerging trends in acquired neonatal intestinal disease: is it time to abandon Bell's criteria? J Perinatol. 2007;27:661–671. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balda M.S., Fallon M.B., Van Itallie C.M., Anderson J.M. Structure, regulation, and pathophysiology of tight junctions in the gastrointestinal tract. Yale J Biol Med. 1992;65:725–735. discussion 737–740. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson J.M., Van Itallie C.M. Tight junctions. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R941–R943. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver L.T., Laker M.F., Nelson R. Intestinal permeability in the newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:236–241. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Elburg R.M., Fetter W.P., Bunkers C.M., Heymans H.S. Intestinal permeability in relation to birth weight and gestational and postnatal age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F52–F55. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.1.F52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foulkes E.C., Mort T.L., Buncher C.R. Intestinal cadmium permeability in mature and immature rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1991;197:477–481. doi: 10.3181/00379727-197-43285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urao M., Okuyama H., Drongowski R.A., Teitelbaum D.H., Coran A.G. Intestinal permeability to small- and large-molecular-weight substances in the newborn rabbit. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1424–1428. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke R.M., Hardy R.N. An analysis of the mechanism of cessation of uptake of macromolecular substances by the intestine of the young rat (“closure”) J Physiol. 1969;204:127–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lecce J.G., Broughton C.W. Cessation of uptake of macromolecules by neonatal guinea pig, hamster and rabbit intestinal epithelium (closure) and transport into blood. J Nutr. 1973;103:744–750. doi: 10.1093/jn/103.5.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dvorak B. Milk epidermal growth factor and gut protection. J Pediatr. 2010;156:S31–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henning S.J. Development of the gastrointestinal tract. Proc Nutr Soc. 1986;45:39–44. doi: 10.1079/pns19860033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaedler R.W., Dubos R., Costello R. The development of the bacterial flora in the gastrointestinal tract of mice. J Exp Med. 1965;122:59–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.122.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper L.V., Wong M.H., Thelin A., Hansson L., Falk P.G., Gordon J.I. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laukoetter M.G., Bruewer M., Nusrat A. Regulation of the intestinal epithelial barrier by the apical junctional complex. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:85–89. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000203864.48255.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piena-Spoel M., Albers M.J., ten Kate J., Tibboel D. Intestinal permeability in newborns with necrotizing enterocolitis and controls: does the sugar absorption test provide guidelines for the time to (re-)introduce enteral nutrition? J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:587–592. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.22288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weaver L.T., Laker M.F., Nelson R., Lucas A. Milk feeding and changes in intestinal permeability and morphology in the newborn. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:351–358. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotten C.M., Taylor S., Stoll B., Goldberg R.N., Hansen N.I., Sanchez P.J., Ambalavanan N., Benjamin D.K., Jr Prolonged duration of initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with increased rates of necrotizing enterocolitis and death for extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2009;123:58–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal R., Sharma N., Chaudhry R., Deorari A., Paul V.K., Gewolb I.H., Panigrahi P. Effects of oral Lactobacillus GG on enteric microflora in low-birth-weight neonates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:397–402. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guandalini S. Update on the role of probiotics in the therapy of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:47–54. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolvers D., Antoine J.M., Myllyluoma E., Schrezenmeir J., Szajewska H., Rijkers G.T. Guidance for substantiating the evidence for beneficial effects of probiotics: prevention and management of infections by probiotics. J Nutr. 2010;140:698S–712S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rakoff-Nahoum S., Paglino J., Eslami-Varzaneh F., Edberg S., Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gassler N., Rohr C., Schneider A., Kartenbeck J., Bach A., Obermuller N., Otto H.F., Autschbach F. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with changes of enterocytic junctions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G216–G228. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark J.A., Doelle S.M., Halpern M.D., Saunders T.A., Holubec H., Dvorak K., Boitano S.A., Dvorak B. Intestinal barrier failure during experimental necrotizing enterocolitis: protective effect of EGF treatment. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G938–G949. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00090.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiou S.R., Yu Y., Chen S., Ciancio M.J., Petrof E.O., Sun J., Claud E.C. Erythropoietin protects intestinal epithelial barrier function and lowers the incidence of experimental neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12123–12132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCracken V.J., Lorenz R.G. The gastrointestinal ecosystem: a precarious alliance among epithelium, immunity and microbiota. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lecce J.G. Absorption of macromolecules by neonatal intestine. Biol Neonat. 1965;9:50–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes J.L., Van Itallie C.M., Rasmussen J.E., Anderson J.M. Claudin profiling in the mouse during postnatal intestinal development and along the gastrointestinal tract reveals complex expression patterns. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanders C.J., Yu Y., Moore D.A., 3rd, Williams I.R., Gewirtz A.T. Humoral immune response to flagellin requires T cells and activation of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2006;177:2810–2818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang S.S., Bloom S.M., Norian L.A., Geske M.J., Flavell R.A., Stappenbeck T.S., Allen P.M. An antibiotic-responsive mouse model of fulminant ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cecal enlargement in germ-free animals. Nutr Rev. 1960;18:313–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1960.tb01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin P.W., Myers L.E., Ray L., Song S.C., Nasr T.R., Berardinelli A.J., Kundu K., Murthy N., Hansen J.M., Neish A.S. Lactobacillus rhamnosus blocks inflammatory signaling in vivo via reactive oxygen species generation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin P.W., Nasr T.R., Berardinelli A.J., Kumar A., Neish A.S. The probiotic Lactobacillus GG may augment intestinal host defense by regulating apoptosis and promoting cytoprotective responses in the developing murine gut. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:511–516. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181827c0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laukoetter M.G., Nava P., Lee W.Y., Severson E.A., Capaldo C.T., Babbin B.A., Williams I.R., Koval M., Peatman E., Campbell J.A., Dermody T.S., Nusrat A., Parkos C.A. JAM-A regulates permeability and inflammation in the intestine in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3067–3076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Claud E.C., Zhang X., Petrof E.O., Sun J. Developmentally regulated tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation in intestinal epithelium. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1411–G1419. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00557.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leaphart C.L., Cavallo J., Gribar S.C., Cetin S., Li J., Branca M.F., Dubowski T.D., Sodhi C.P., Hackam D.J. A critical role for TLR4 in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis by modulating intestinal injury and repair. J Immunol. 2007;179:4808–4820. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tatum P.M., Jr, Harmon C.M., Lorenz R.G., Dimmitt R.A. Toll-like receptor 4 is protective against neonatal murine ischemia-reperfusion intestinal injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1246–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson J.M., Van Itallie C.M. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002584. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krause G., Winkler L., Mueller S.L., Haseloff R.F., Piontek J., Blasig I.E. Structure and function of claudins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexandre M.D., Jeansonne B.G., Renegar R.H., Tatum R., Chen Y.H. The first extracellular domain of claudin-7 affects paracellular Cl- permeability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cario E., Gerken G., Podolsky D.K. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gewolb I.H., Schwalbe R.S., Taciak V.L., Harrison T.S., Panigrahi P. Stool microflora in extremely low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;80:F167–F173. doi: 10.1136/fn.80.3.f167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henry M.C., Moss L.R. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:98–109. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neu J. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: an update. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2005;94:100–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markov A.G., Veshnyakova A., Fromm M., Amasheh M., Amasheh S. Segmental expression of claudin proteins correlates with tight junction barrier properties in rat intestine. J Comp Physiol B. 2010;180:591–598. doi: 10.1007/s00360-009-0440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahner C., Mitic L.L., Anderson J.M. Heterogeneity in expression and subcellular localization of claudins 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the rat liver, pancreas, and gut. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:411–422. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thuijls G., Derikx J.P., de Haan J.J., Grootjans J., de Bruine A., Masclee A.A., Heineman E., Buurman W.A. Urine-based detection of intestinal tight junction loss. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e14–e19. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31819f5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thuijls G., Derikx J.P., van Wijck K., Zimmermann L.J., Degraeuwe P.L., Mulder T.L., Van der Zee D.C., Brouwers H.A., Verhoeven B.H., van Heurn L.W., Kramer B.W., Buurman W.A., Heineman E. Non-invasive markers for early diagnosis and determination of the severity of necrotizing enterocolitis. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1174–1180. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d778c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Itallie C.M., Anderson J.M. The molecular physiology of tight junction pores. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:331–338. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00027.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li W.Y., Huey C.L., Yu A.S. Expression of claudin-7 and -8 along the mouse nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F1063–F1071. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00384.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fak F., Ahrne S., Molin G., Jeppsson B., Westrom B. Microbial manipulation of the rat dam changes bacterial colonization and alters properties of the gut in her offspring. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G148–G154. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00023.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin P.W., Nasr T.R., Stoll B.J. Necrotizing enterocolitis: recent scientific advances in pathophysiology and prevention. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:70–82. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin P.W., Stoll B.J. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 2006;368:1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mshvildadze M., Neu J., Mai V. Intestinal microbiota development in the premature neonate: establishment of a lasting commensal relationship? Nutr Rev. 2008;66:658–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isolauri E., Kaila M., Arvola T., Majamaa H., Rantala I., Virtanen E., Arvilommi H. Diet during rotavirus enteritis affects jejunal permeability to macromolecules in suckling rats. Pediatr Res. 1993;33:548–553. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199306000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li N., Russell W.M., Douglas-Escobar M., Hauser N., Lopez M., Neu J. Live and heat-killed Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG): effects on proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in gastrostomy-fed infant rats. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:203–207. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181aabd4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kunz A.N., Fairchok M.P., Noel J.M. Lactobacillus sepsis associated with probiotic therapy. Pediatrics. 2005;116:517. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0475. author reply 517–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Land M.H., Rouster-Stevens K., Woods C.R., Cannon M.L., Cnota J., Shetty A.K. Lactobacillus sepsis associated with probiotic therapy. Pediatrics. 2005;115:178–181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cilieborg M.S., Thymann T., Siggers R., Boye M., Bering S.B., Jensen B.B., Sangild P.T. The incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis is increased following probiotic administration to preterm pigs. J Nutr. 2011;141:223–230. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.128561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cecal enlargement in antibiotic-treated mice. Cecal enlargement demonstrated in antibiotic-treated (Abx) mice versus wild-type (WT) controls at the age of 3 weeks.

LGG crosses the immature intestinal epithelial barrier of 2-week-old mice. Representative confocal images from 2-week-old mice fed fluorescently labeled LGG (red), demonstrating bacteria (arrows) in the lumen (A) and lamina propria (B) of distal small-intestinal sections. Epithelia were labeled with anti-phalloidin (green).