Abstract

The nuclear receptor coactivator amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1/SRC-3) has a well-defined role in steroid and growth factor signaling in cancer and normal epithelial cells. Less is known about its function in stromal cells, although AIB1/SRC-3 is up-regulated in tumor stroma and may, thus, contribute to tumor angiogenesis. Herein, we show that AIB1/SRC-3 depletion from cultured endothelial cells reduces their proliferation and motility in response to growth factors and prevents the formation of intact monolayers with tight junctions and of endothelial tubes. In AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice, the angiogenic responses to subcutaneous Matrigel implants was reduced by two-thirds, and exogenously added fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 did not overcome this deficiency. Furthermore, AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice showed similarly delayed healing of full-thickness excisional skin wounds, indicating that both alleles were required for proper tissue repair. Analysis of this defective wound healing showed reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells and macrophages, cytokine induction, and metalloprotease activity. Skin grafts from animals with different AIB1 genotypes and subsequent wounding of the grafts revealed that the defective healing was attributable to local factors and not to defective bone marrow responses. Indeed, wounds in AIB1+/− mice showed reduced expression of FGF10, FGFBP3, FGFR1, FGFR2b, and FGFR3, major local drivers of angiogenesis. We conclude that AIB1/SRC-3 modulates stromal cell responses via cross-talk with the FGF signaling pathway.

AIB1 is the third member of the nuclear coactivator or p160 steroid receptor coactivator (SRC-3) family that promotes transcriptional activity of multiple nuclear receptors, such as the estrogen receptor,1 and other transcription factors, including E2F-1, AP-1, NFκB, and STAT6.2–5 AIB1/SRC-3 has also been shown to be important in a diverse set of growth factor signaling pathways, such as insulinlike growth factor 1 and growth hormone signaling in normal mouse fibroblasts and hepatocytes,6 insulinlike growth factor 1 in breast cancer epithelium,7 and epidermal growth factor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) signaling in cancer epithelial cells.8,9 Multiple studies have shown that the AIB1 gene is amplified and overexpressed in breast10 and other human1,11–15 cancers. High levels of AIB1 mRNA or protein predict significantly worse prognosis and overall survival in patients with breast cancer.10 Animal models corroborate the role of AIB1 as an oncogene since expression of AIB1 under the control of mouse mammary tumor virus in transgenic mice induced mammary hyperplasia and tumors.16,17 Complementary to this, AIB1 knockout in mice prevented HER2 oncogene or carcinogen-induced mammary carcinogenesis.9,18

Although the coactivators in the SRC family are thought of mainly as oncogenes that affect epithelial responses to external hormone, growth factor, and cytokine signals,10,19 analysis of recently published human cancer expression array data20,21 reveals significant increases in AIB1/SRC-3 expression in the stromal compartment of breast cancers (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), suggesting a potential role of AIB1 expression in the stromal response during malignant progression. A potential impact of AIB1/SRC-3 on tumor stroma was also suggested from reduced angiogenesis in mammary and thyroid tumors in AIB1/SRC-3 knockout mice.9,22

At the cellular and molecular levels, there are many parallels between a healing wound and processes ongoing in the tumor and surrounding stroma.23 Some 150 years ago, Rudolf Virchow (1863)24 viewed tissue injury and repair as part of the malignant process, and tumors have been described as “wounds that will not heal.”25 An important component of wound healing is the formation of new blood vessels that is controlled by a well-orchestrated set of different drivers that can be dysregulated in tumors.26–28 To address the contribution of AIB1/SRC-3 to stromal responses, we assessed the impact of AIB1/SRC-3 depletion on endothelial cell function in vitro and evaluated the effect on neoangiogenesis and wound healing in AIB1/SRC-3 knockout animals. In addition, excisional wound healing in full-thickness skin transplants from and into different AIB1/SRC-3 genotype animals were used to distinguish between local and systemic factors. We found that AIB1/SRC-3 has a major role in the local control of wound healing, affecting different aspects of the stromal response and major drivers in the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling pathway, ie, FGF10, FGFBP3, FGFR1, FGFR2b, and FGFR3. It is striking that AIB1/SRC-3 is up-regulated not only in tumor stroma but also in healing wounds, suggesting a broader role in stromal function.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were maintained in endothelial basal medium-2 (Lonza Inc., Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum as recommended by the supplier. AIB1/SRC-3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts,29 NIH3T3, and human foreskin fibroblasts (Hs-27) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Short Hairpin RNA Constructs and Lentivirus Infection

Control scrambled short hairpin RNA (shRNA)30 was purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). AIB1 shRNA #1 (5′-TGGTGAATCGAGACGGAAACA-3′) and #2 (5′-GCAGTCTATTCGTCCTCCATA-3′)29 were subcloned into the EcoRI and AgeI restriction sites in PLKO.1 puro (Addgene). Lentivirus production was performed as described elsewhere31 using the recommended protocols for production of lentiviral particles with packaging plasmid (pCMV-dR8.2 dvpr) and envelope plasmid (pCMV-VSVG) (Addgene).

Tube Formation Assay

HUVECs infected with control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA lentivirus for 48 hours were plated in Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ)-coated 8-well chamber slides (3 × 105 cells per well) as described.32 Tube formation was imaged, and tube diameters were quantitated at 18 hours using NIH ImageJ software.

Monolayer Formation Assay

Control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA-infected HUVECs (2 × 105) were plated in wells of the electric cell-substrate impedance sensor system (8W10E; Applied BioPhysics, Troy, NY). Analysis of the monolayer was performed after 20 hours. Details are provided in studies by Wellstein and colleagues.33,34

Cell Migration Assay

A denuded area in control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA-infected HUVEC confluent monolayers was generated by scraping with a micropipette tip. The extent of migration was determined in the presence or absence of mitomycin C (2 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by measuring the distance between the migration fronts at 0, 24, and 48 hours. Quantification from five independent digitized images was performed using NIH ImageJ software. Control and shRNA-infected Hs-27 cells were plated in 12-well plates. Cell culture inserts to generate 0.5-mm-diameter, rectangular, cell-free spaces (ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) were placed into the wells and then were removed after 24 hours. Time-lapse phase-contrast microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope system; Nikon, Melville, NY) was used to continuously capture images and follow migration at different time points to calculate migration rates.

Proliferation Assays

One thousand control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA-infected HUVECs were plated in 96-well plates. Cell proliferation was measured at 24, 48, and 72 hours using CellTiter-Glo (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Alternatively, cells were stained with crystal violet (0.52% crystal violet in 25% methanol). After washing the cells to remove excess stain, the plates were dried and the bound stain was solubilized by the addition of 100 μL of 100 mmol/L sodium citrate in 50% ethanol. Staining intensity, which is proportional to cell number, was then determined by measuring absorbance at 570 nm using a 96-well plate reader.

Apoptosis Assay

Apoptosis in control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA-infected HUVECs (2 × 105 cells) was determined by annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate staining (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions 48 hours after infection.

Studies in Animals

The generation of mice with different AIB1/SRC-3 genotypes (+/+, +/−, and −/−) is as previously described.9 Animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Matrigel Plug Assay

Growth factor–depleted Matrigel (0.5 mL) without and with FGF2 (10 μg/mL) was injected subcutaneously into 3- to 4-month-old mice. Five days later, the Matrigel plugs were harvested, and 5-μm sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were stained with H&E. The number of endothelial cell nuclei was counted in 10 random fields at ×40 magnification.

Wound-Healing Assay

A 3-mm-diameter dermal biopsy punch (Miltex Inc., Bethpage, NY) was used to generate four full-thickness skin wounds through the skin and panniculus carnosus muscle in anesthetized animals (3- to 4-month-old males), and they were left to heal. After wounding, the animals were euthanized, and wounded tissues were harvested at the times indicated. Histologic sections were cut rectangular to the skin surface across the wound. Serial paraffin-embedded tissue sections (5 μm) were stained with H&E and were analyzed by three observers blinded to the design. Photographs of open wound areas at different times (1 to 8 days) after injury were quantified using NIH ImageJ software. The distance between the epithelial tips was measured in day 5 wound microphotographs using NIH ImageJ software and the following formula: (Wound Diameter − Length of Epithelial Tongues).

Immunohistochemical Analyses

Immunohistochemical analyses for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PNCA; Sigma-Aldrich), F4/80 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and AIB1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were performed on wound sections as previously described.9,35 F4/80, VEGF-A, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen–positive cells were counted in 5 to 10 nonoverlapping visual fields.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA from wounded tissues and bone marrow was extracted using the RNeasy fibrous mini kit and RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturers's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using the iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) under the following conditions: 95°C for 3 minutes followed by 40 cycles (95°C for 20 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 40 seconds). PCR primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of Signaling Molecules in Wounds

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| CD105 | 5′-TTTGTACCCACAACAGGTCTCGCA-3′ | 5′-AACGTGGACTTCACGCACAGCATT-3′ |

| Thy1 | 5′-AGCCAACTTCACCACCAAGGATGA-3′ | 5′-GCCACACTTGACCAGCTTGTCTCTAT-3′ |

| Bst1 | 5′-TGCGACGTGCTGTATGGCAAAGTT-3′ | 5′-TTCCAATAGGAGTCCACGGCGTTGTT-3′ |

| CD14 | 5′-ACATCTTGAACCTCCGCAACGTGT-3′ | 5′-TTGAGCGAGTGTGCTTGGGCAATA-3′ |

| CD16 | 5′-TTGCAGTGGACACGGGCCTTTATT-3′ | 5′-TTGTCTTGAGGAGCCTGGTGCTTT-3′ |

| CD133 | 5′-AAGATGCAGCCACCCAGCTCAATA-3′ | 5′-ATGCTATCGCAGATCTTGCTGGCT-3′ |

| CD31 | 5′-AGCTAGCAAGAAGCAGGAAGGACA-3′ | 5′-TAAGGTGGCGATGACCACTCCAAT-3′ |

| CD34 | 5′-CCATTTCTCCTCTCTCGCCTCTTCA-3′ | 5′-AGTTTCCTGGGAAGAAGTGGTAGC-3′ |

| CD45 | 5′-GGGTTGTTCTGTGCCTTGTT-3′ | 5′-GGATAGATGCTGGCGATGAT-3′ |

| F4/80 | 5′-GGGACAAACACTTGGTGGTGTGAA-3′ | 5′-CCTGGGCCTTGAAAGTTGGTTTGT-3′ |

| FGF7 | 5′-GAACAGCTACAACATCATGGAAA-3′ | 5′-CATAGAGTTTCCCTTCCTTGTTC-3′ |

| FGF10 | 5′-GCCTCAGCCTTTCCCCAC-3′ | 5′-CTTGGCAGGTGACAGGGAAC-3′ |

| FGFBP1 | 5′-GAGGCAGCCTGAAGTCTC-3′ | 5′-GGAGTCTCATCACGTCAGC-3′ |

| FGFBP3 | 5′-AGCCCTTGCTAGTGAAGTCCAACT-3′ | 5′-TAGGTCTCAGTGAGCTCGGCATT-3′ |

| FGFR1 | 5′-GTAGCTCCCTACTGGACATCC-3′ | 5′-GCATAGCGAACCTTGTAGCCTC-3′ |

| FGFR2 | 5′-TGCCCTACCTCAAGGTCCTG-3′ | 5′-TAGAATTACCCGCCAAGCAC-3′ |

| FGFR3 | 5′-CCTCAGGAGATGACGAAGATGGG-3′ | 5′-GCAGTTTCTTATCCATTCGCTCCG-3′ |

| FGFR4 | 5′-ATGACCGTCGTACACAATCTTAC-3′ | 5′-TGTCCAGTAGGGTGCTTGC-3′ |

| FGFR1b | 5′-TACGCTTGCGTGACCAGCAGC-3′ | 5′-CTACAGGCCTACGGTTTGGTTTGG-3′ |

| FGFR1c | 5′-ACGGACAACACCAAACCAAACCCTG-3′ | 5′-GGTGTCCCACTCGACGGGCA-3′ |

| FGFR2b | 5′-TAGCTCCAATGCAGAAGTGCTGGC-3′ | 5′-AGGCGCTTGCTGTTTGGGCAG-3′ |

| FGFR2c | 5′-GCCCGGCCCTCCTTCAGTTTAG-3′ | 5′-TAGTCCAACTGATCACGGCGGC-3′ |

| FGFR3b | 5′-GCGATGCACAGCCACACATCCA-3′ | 5′-GTGCGTCTGCCTCCACATTCTCACT-3′ |

| FGFR3c | 5′-GAGACGGAGCCGCGCGTGTC-3′ | 5′-ACGCAGGCCGGGACTACCATG-3′ |

| mAIB1 | 5′-AGTGGACTAGGCGAAAGCTCT-3′ | 5′-GTTGTCGATGTCGCTGAGATTT-3′ |

In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging

A broad-range fluorescence activatable substrate (2 nmol) (MMPsense 750 FAST; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) 2, 3, 7, 9, 12, and 13 that is optically silenced on injection was injected into the mouse tail vein 1 day after wounding. In vivo fluorescence imaging was performed on days 2 through 8 after wounding using a Maestro in vivo imaging system (PerkinElmer) (excitation wavelength = 641 to 681 nm, emission wavelength = 700 to 950 nm). Spectral analysis of the images was conducted using the Maestro software by unmixing the pure spectrum of the agent from the autofluorescence of the mice before injection. The fluorescence signal of areas around each wound was quantified and averaged among the four wounds.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described elsewhere.7 Western blot analyses for AIB1, phospho–mitogen-activated protein kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase, phospho-Akt, Akt, phospho-p38, and p38 (Cell Signaling Technology) were performed with the respective rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Immunoblot analyses for human actin were performed using a respective mouse monoclonal antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA).

Expression Analysis

The expression profile of 84 angiogenesis-related genes was determined using a 96-well format mouse angiogenesis RT2 Profiler PCR array (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purification of total RNA prepared from 4-day wounds and cDNA preparation are described in Quantitative Real-Time PCR. Quantitative PCR was performed using the RT2 SYBR green quantitative PCR master mixes (SABiosciences).

Skin Transplants

Full-thickness skin was taken from the ears of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice (donors) and was transplanted onto the backs of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice (recipients), respectively.36 On day 9 after grafting, the transplants had healed and a 3-mm-diameter dermal biopsy punch (Miltex Inc) was used to generate full-thickness skin wounds through the grafted skin in anesthetized animals (3- to 4-month-old males), and they were left to heal. Photographs of open wound areas at different times after wounding were quantified using NIH ImageJ software.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Experiments were performed three times unless noted otherwise in the figure legend. GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis and for nonlinear regression analysis. Analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons and t tests for paired comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 unless stated otherwise.

Results

AIB1/SRC-3 Depletion Impairs Endothelial Cell Function in Vitro

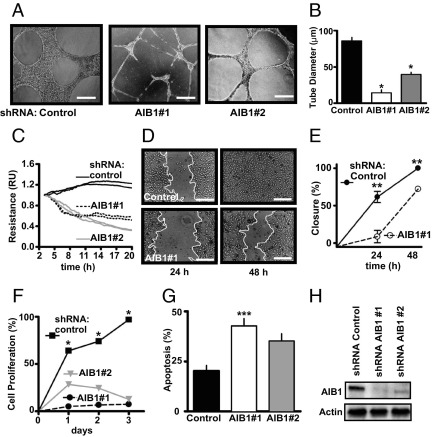

To assess the effect of AIB1/SRC-3 to modulate the ability of endothelial cells to sprout in response to appropriate cues, a tube formation assay in collagen was used.32 Depletion of AIB1/SRC-3 by shRNA silencing disrupted the ability of endothelial cells (HUVECs) to form tubes and reduced the average diameter of the tubes (Figure 1, A and B). Endothelial cells form the barrier layer between the bloodstream and the parenchyma, and we, thus, monitored the impact of AIB1/SRC-3 depletion on the ability of endothelial cells to form monolayers with tight junctions using electric cell-substrate impedance sensing as described elsewhere.33,34 On AIB1/SRC-3 depletion, endothelial monolayer resistance dropped by >50% (Figure 1C), suggesting a reduction in barrier function. Beyond this steady-state barrier function of endothelial cells, the repair of an endothelial monolayer in vitro can be used to assess the potential effect on the repair of endothelia in vivo. In an in vitro scratch assay, depletion of AIB1/SRC-3 in endothelial cells resulted in a delay of migration toward the denuded area compared with control cells (Figure 1, D and E) and an increased fraction of cells undergoing reduced proliferation and apoptosis (Figure 1, F and G; see also Supplemental Figure S2, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). This delay in scratch closure was not due to lack of proliferation of the endothelial cells since the same result was obtained in the presence of mitomycin C (see Supplemental Figure S2, C and D, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Moreover, the effects we observed in endothelial cells are not due to shRNA off-target effects since two distinct AIB1/SRC-3–targeted shRNAs (Figure 1H) caused similar changes in phenotype. Taken together, these data suggest that AIB1/SRC-3 is important for endothelial-specific functions that include tube and monolayer formation.

Figure 1.

Effect of AIB1/SRC-3 depletion on endothelial cell function in vitro. Endogenous AIB1/SRC-3 was depleted by infection of HUVECs with lentiviral vectors expressing shRNAs targeting two distinct sequences in AIB1/SRC-3 (AIB1 #1 or #2) or scrambled shRNA (control). Representative images of tube formation in Matrigel (A) and quantitation of tube diameter (B). Scale bars: 0.1 mm. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of two independent experiments. *P < 0.0001 versus control. C: Electrical resistance of endothelial cell monolayers formed on microelectrodes was monitored at 15-second intervals over a 20-hour period. Resistance is shown relative to 3 hours after cell plating and is representative of one of three independent experiments in duplicate wells. D: Representative images of repair of denuded endothelial monolayer areas by cell migration at 24 and 48 hours, with the white line indicating the migration front of cells. Scale bars: 0.1 mm. E: Quantitation of the closure of the denuded area. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.001 versus control. F: Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of three independent cell proliferation experiments performed in triplicate. *P < 0.0001 versus control. G: Annexin V–positive (apoptotic) cells 48 hours after AIB1/SRC-3 depletion. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.05 versus control. The corresponding fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis is shown in Supplemental Figure S2A (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). H: Western blot analysis for AIB1 protein in HUVECs infected with a scrambled control shRNA or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA #1 and #2 48 hours after infection. The blots are representative of three experiments.

To determine whether AIB1/SRC-3 showed a role in other stromal cell types, we examined different fibroblast cell lines. Proliferation of mouse or human fibroblasts was unaffected by the depletion or overexpression of AIB1/SRC-3 (see Supplemental Figure S3, A–D, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), although the motility of human fibroblasts in a scratch assay was impaired by AIB1/SRC-3 loss (see Supplemental Figure S3, E and F, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data suggest distinct roles of AIB1/SRC-3 in different stromal cell types.

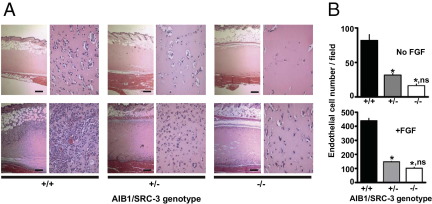

Role of AIB1/SRC-3 for Angiogenesis in Vivo

We previously observed that angiogenesis is reduced in mammary tumors of mouse mammary tumor virus–HER2/Neu mice when comparing AIB1/SRC-3+/− and +/+ genotype mice, whereas −/− mice did not form tumors at all.9 To investigate the effect of AIB1/SRC-3 genotype on angiogenesis, we used a Matrigel plug assay. Matrigel is placed subcutaneously, and neoangiogenesis can be monitored by increased mRNA expression of endothelial marker CD31 and loss of inflammatory marker CD14 in the plug (see Supplemental Figure S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), without the influence of an epithelial component. Histologic analysis and quantitation of the relative number of endothelial cells after a fixed time showed that endothelial cell invasion into the plugs of AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice was significantly reduced compared with that of +/+ mice (Figure 2). The induction of angiogenesis in this assay is driven by locally released growth factors due to the subcutaneous wound caused by the Matrigel injection. We next tested whether supplementation of the Matrigel plugs with an excess of FGF2 would restore angiogenesis to similar levels across the different AIB1/SRC-3 genotypes. Addition of FGF2 induced a significant, 5.5-fold angiogenic response in AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice relative to baseline levels. However, AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice still showed significantly reduced angiogenesis even with the added FGF2 (Figure 2). We conclude that the loss of AIB1/SRC-3 results in a reduced capacity to mount an angiogenic response to a subcutaneous injury that cannot be rescued by an excess of FGF2. Also, it seems that the loss of a single AIB1/SRC-3 allele, ie, in +/− mice, reduces the angiogenic response by 70% to 90% (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of AIB1/SRC-3 on angiogenesis. Neoangiogenesis in subcutaneous Matrigel plugs injected subcutaneously into AIB1/SRC-3+/+, +/−, or −/− mice was monitored. A: Representative H&E-stained cross sections at ×4 (left of each pair) and ×10 (right of each pair) magnification of Matrigel plugs without (top row) and with FGF2 added (10 μg/mL) 5 days after implantation (bottom row). Scale bars: 0.25 mm. B: Number of endothelial cell nuclei in the plugs from 10 high-power fields per plug. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 to 5 animals per group). *P < 0.0001 versus AIB1/SRC-3+/+; ns, P > 0.05 AIB1/SRC-3+/− versus −/−.

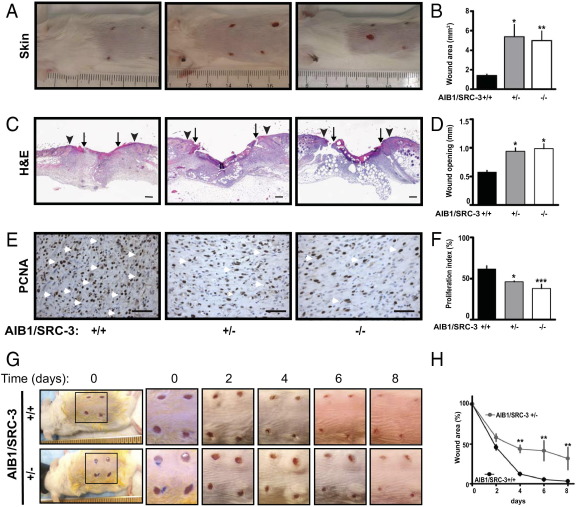

Role of AIB1/SRC-3 in the Healing of Full-Thickness Skin Wounds

From the defective neoangiogenic response in AIB1/SRC-3 knockout mice, we hypothesized that AIB1/SRC-3 might impact tissue repair processes and we examined the healing of full-thickness skin wounds to test this hypothesis. In mammals, wound healing is a well-characterized process that requires defined inflammatory, proteolytic, tissue remodeling, and angiogenic responses.37 We found that 5 days after wounding, skin wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice showed a macroscopic greater wound opening and a distinctly inflamed appearance compared with +/+ mice. The latter showed more complete healing of the lesions with no evidence of residual inflammation (Figure 3A). Analysis of the digitized images of the wound areas revealed a significant wound closure delay in AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice, with mean ± SEM wound openings of 5.4 ± 1.3 and 4.9 ± 0.9 mm2, respectively, versus 1.4 ± 0.1 mm2 in +/+ mice (Figure 3, A and B). Measurement of the distance between the epithelial tips under the incisional injury scab indicated that AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice had significantly reduced epithelial closure relative to +/+ animals (mean ± SEM: 0.9 ± 0.06 and 0.98 ± 0.085 mm, respectively, versus 0.57 ± 0.03 mm; Figure 3, C and D). Staining for PCNA in the granulation tissue (Figure 3E) in the hyperproliferative epithelium at the wound edge (see Supplemental Figure S5A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) showed a significantly lower number of proliferating cells of AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice relative to +/+ animals (Figure 3F; see also Supplemental Figure S5B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Note that AIB1/SRC-3 protein levels measured by immunohistochemical analysis were reduced significantly in the healthy skin and granulation tissue of AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice relative to controls and were not detectable in −/− mice (see Supplemental Figure S5C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Still, the extent of defective wound healing in the AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice showed no significant difference (Figure 3, B, D, and F), indicating that the loss of one AIB1/SRC-3 allele was sufficient to maximally impede the wound-healing response. Since homozygous AIB1/SRC-3−/− mice have reduced reproductive function and viability38 in contrast to heterozygous AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice, we used +/− mice for further in-depth analyses of the wound-healing response. Wound healing of AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice and their control +/+ littermates was observed over an 8-day period (Figure 3G). Differences in wound closure became apparent by day 4 after wounding and were sustained throughout the healing process. In fact, day 8 wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice exhibited almost complete closure, whereas those from +/− mice still showed a 40% opening (Figure 3H). Histologic analysis revealed well-progressing healing over time that was characterized by mature granulation tissue, continuous wound contraction, and reepithelialization in controls. This was accompanied by the presence of superficial neutrophils at the base of the scab, migrating and proliferating spindled fibroblasts and macrophages, gradual increase of infiltrating endothelial cells with subsequent neoangiogenesis, and collagen deposition from the base throughout the whole wound area. The different healing features are indicated in Supplemental Figure S5D (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In contrast, wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice showed a significantly slower healing process with poorer wound contraction, delayed fibrin breakdown, and very little collagen deposition. Immature granulation tissue was mainly present at the periphery of the wound, with fewer infiltrating cells and delayed neoangiogenesis (see Supplemental Figure S5D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 3.

Effect of AIB1/SRC-3 on skin wound healing. Macroscopic images (A) and quantitation (B) of the open wound area of full-thickness dorsal skin wounds on day 5 after injury in AIB1/SRC-3+/+, +/−, and −/− mice. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 to 11 animals per genotype). *P < 0.001, **P < 0.0001 versus control. C: Representative H&E-stained sections of excisional skin wounds on day 5 after wounding. Arrowheads, wound edges; arrows, tips of epithelial tongues. Scale bars: 0.2 mm. D: Quantitation of wound reepithelialization, as described in Materials and Methods. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 to 5 animals per group). *P < 0.001 versus control. E: PCNA staining (brown) of proliferating cells (arrowheads) in the wound granulation tissue. Scale bars: 0.1 mm. F: Quantitation of the PCNA-positive nuclei. Proliferation index = PCNA-positive cell nuclei per 100 cells. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 to 4 animals per group). *P < 0.001, ***P < 0.05 versus control. Macroscopic images (G) and quantitation (H) of the wound-healing time course of open wound areas in AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice relative to day 0. Values are given as the mean ± SEM. **P < 0.0001 versus control.

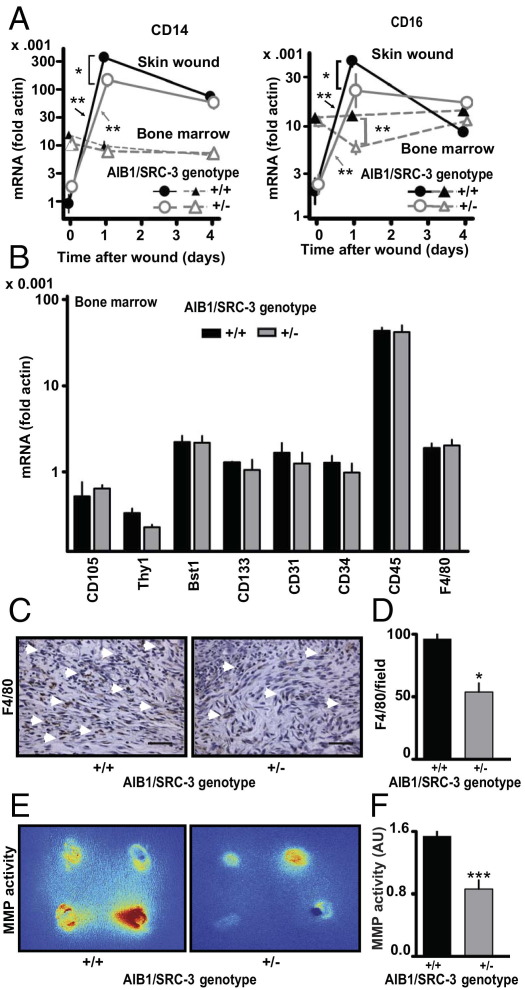

Contribution of AIB1/SRC-3 to the Inflammatory and Angiogenic Responses during Wound Healing

The inflammatory response is characteristic of the early phase of wound healing.39 Consistent with the notion of rapid recruitment of inflammatory cells, such as monocytes and macrophages, which express CD14 and CD16+ markers, 1 day after wounding there was a >300-fold increase in CD14 expression and a >50-fold increase in CD16 expression in the wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice compared with nonwounded skin (Figure 4A). In contrast, increases in CD14 and CD16 levels in wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice were significantly smaller than those from +/+ mice. In day 4 wounds, the levels of CD14 and CD16 decreased and were no longer different between AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice (Figure 4A). This finding suggests that the impact of AIB1/SRC-3 on inflammatory cell recruitment occurs during the initial response to injury. This difference in inflammatory response could be due to changes in the complement of immune and endothelial progenitor cells in the bone marrow of the different AIB1/SRC-3 genotypes. However, the expression levels of a diverse set of hematopoietic, mesenchymal stem cell, and proinflammatory markers showed no significant differences between bone marrow of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of AIB1/SRC-3 on the inflammatory response and MMP activity during wound healing. A: CD14 and CD16 mRNA expression in wounds and bone marrow on days 0, 1, and 4 after injury. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype). *P < 0.001, **P < 0.0001. B: Hematopoietic, mesenchymal stem cell, and proinflammatory marker mRNA expression in bone marrow of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice per group). C: Staining of granulation tissue of day 5 wounds for F4/80-positive macrophages (arrowheads). Scale bars: 0.1 mm. D: Number of F4/80-positive macrophages invading the granulation in five nonoverlapping visual fields. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 to 4 animals per group). *P < 0.001 versus control. E: Representative images of fluorescent activatable MMP substrate in day 3 wounds. Four wounds per animal, with an approximate mean diameter of 3 mm, are visible (also see Figure 3A). The color represents signal intensity ranges from red (highest activity) to blue (lowest activity). F: Quantitation of MMP activity. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 animals per group). ***P < 0.05 versus control. Details and a full time course of MMP activity are given in Supplemental Figure S8 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

To directly assess the local contribution of the altered AIB1/SRC-3 genotype, we transplanted skin from AIB1/SRC-3+/− and +/+ mice onto +/+ or +/− mice, respectively. Within 2 weeks, these grafts healed-in, and full-thickness excisional wounds were then generated in the center of the grafts. Image analysis of the wounds was used to assess the impact of the recipient and donor genotype on wound closure (see Supplemental Figure S6 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Note that in this crossover study, each host animal carried grafts from both donor genotypes. It was striking that wounds in skin grafts from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ donors healed significantly better than did grafts from +/− donors irrespective of the recipient host genotype. This finding suggests that AIB1/SRC-3 mostly affects locally acting drivers rather than cells or soluble factors in the circulation of the host or bone marrow cells induced and recruited during wound healing.

Note that AIB1/SRC-3 mRNA levels in the wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice were up-regulated twofold 1 day after wounding and returned to control levels after 4 days, whereas no such changes were found in the wounds of +/− mice (see Supplemental Figure S7 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). AIB1 mRNA in the wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice were reduced by 80% relative to the peak levels in +/+ mice, and AIB1 protein levels in the wound also corroborate this observation (see Supplemental Figure S5B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). This might explain why the delayed wound-healing response in the homozygous AIB1/SRC-3−/− mice and the heterozygous +/− mice was indistinguishable (Figure 3, A–F). Consistent with the impact of AIB1/SRC-3 silencing on the local inflammatory response, wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice showed a significant reduction by 55% in F4/80 staining of mature macrophages relative to +/+ mice (Figure 4, C and D), whereas the analysis of bone marrow in +/+ versus +/− mice did not show a difference in F4/80 levels (Figure 4B).

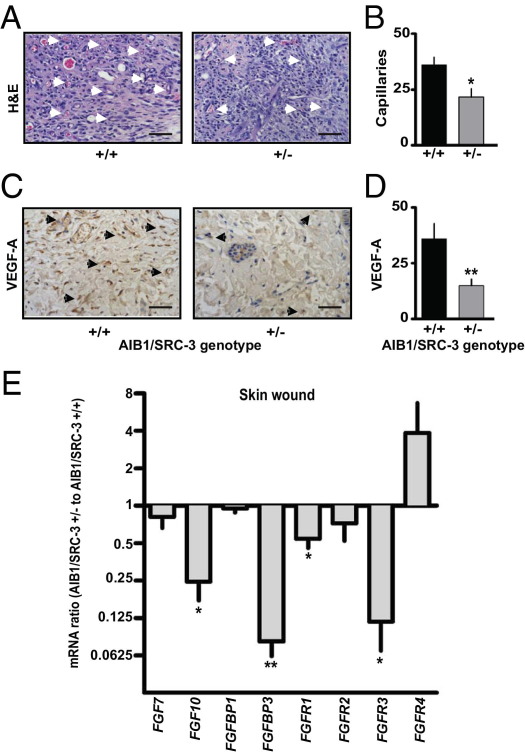

Another hallmark of wound healing and tissue remodeling is the production of MMPs predominantly by the inflammatory cells and macrophages that promote extracellular matrix breakdown.37,40 MMP activity is also a feature of tissue remodeling during tumorigenesis.41 We, therefore, examined, by in vivo imaging, the overall activity of MMPs (MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, MMP-12, and MMP-13) in the wounds by monitoring an MMP activatable fluorescent substrate that was injected intravenously. Peak levels of MMP activity were observed in AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice 3 days after wounding, with a continuous decrease until day 6 (Figure 4, E and F; see also Supplemental Figure S8 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In contrast, in AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice, MMP activity did not increase above the initial levels and progressively decreased. Also, at all time points, the MMP activity was lower in AIB1/SRC-3+/− than in +/+ mice (see Supplemental Figure S8 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These findings were corroborated by an expression survey of wound-healing–related genes. A significant decrease in MMP-9 mRNA expression in day 4 wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/− versus +/+ mice was observed (see Supplemental Figure S9 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Altogether, these data support the notion of compromised immune cell infiltration and consequently slower extracellular matrix remodeling by MMPs in wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice as a contributing factor to the defective wound healing seen at the macroscopic level. Consistent with a direct effect of AIB1/SRC-3 on endothelial cell function, the number of infiltrating capillaries in the wound granulation tissue of AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice was significantly reduced relative to that of +/+ mice (Figure 5, A and B), and this decrease in neoangiogenesis was consistent with a reduction in VEGF-A immunoreactivity in the same tissues (Figure 5, C and D).

Figure 5.

Effect of AIB1/SRC-3 on wound angiogenesis and FGFR pathway genes. A: Representative H&E-stained sections of the granulation tissue from excisional skin wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice on day 5 after wounding. Arrowheads, capillaries. Scale bars: 0.1 mm. B: Quantitation of the number of neocapillaries across the wound. Values are given as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control. C: Immunostaining of granulation tissue for microvessels with an anti–VEGF-A antibody. Arrowheads, VEGF-A positive endothelial cells. Scale bars: 0.1 mm. D: Quantitation of VEGF-A–positive neocapillaries. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 to 5 animals per genotype group). **P < 0.001 versus control. E: mRNA expression (quantitative PCR) of FGF7, FGF10, FGFBP1, FGFBP3, and FGFR1 to FGFR4 in day 4 skin wounds. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 versus control. Note that mice, in contrast to other vertebrates, lack the FGFBP2 gene.43,44

Driver Pathways of AIB1/SRC-3 Effects during Wound Healing

To assess which signaling pathways are affected by AIB1/SRC-3 during wound healing, we surveyed the expression of a set of known genes involved in wound healing and angiogenesis. Overall, comparison of gene expression patterns in wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ versus +/− mice surveying 84 known angiogenic modulator genes did not show significant changes greater than twofold for most genes represented on the array, including prominent angiogenic factors, such as FGF1 and FGF2. Noteworthy examples of genes with differential expression between wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice were the macrophage-derived cytokine CXCL2 and HIF1-α (see Supplemental Figure S9 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), with seven genes seeming to be up-regulated more than fourfold. Since AIB1/SRC-3 knockout mice failed to fully respond to FGF2 stimulation in the Matrigel assay (Figure 2), we hypothesized that FGF signaling molecules could be likely drivers of the differential wound-healing response of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ versus +/− mice. Also, in an earlier work we had found that AIB1 affects transcription of a secreted FGF-binding protein (FGFBP1)42 that can control angiogenesis,43,44 wound healing,35,45 and vascular permeability.46 We also assessed mRNA expression of FGF7, FGF10, FGF receptors (FGFR1-4), FGFBP1, and FGFBP347–49 in 4-day wounds. Wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice showed significantly lower expression of FGF10, FGFBP3, FGFR1, and FGFR3 compared with +/+ controls (Figure 5E).43,44 Also, the expression ratio of FGFR2b to c splice isoforms was changed in favor of the b-isoform in wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice, whereas the FGFR1 and FGFR3 isoform ratios were not affected (see Supplemental Figure S10 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). FGF10 preferentially signals through FGFR2b,50 and the impact of the increased FGF10 expression in the wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice will, thus, be enhanced together with a difference in overall levels of FGFR1 and FGFR3 in favor of wounds from +/+ mice. The phenotypic effects of AIB1/SRC-3 reduction were also reflected in distinct changes in FGF2-induced signal transduction in endothelial cells in vitro. The induction of phospho–mitogen-activated protein kinase by exogenously added FGF2 was unchanged after AIB1/SRC-3 knockdown, whereas phospho-AKT and phospho-p38 induction were reduced (see Supplemental Figure S11 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Thus, the loss of AIB1 in endothelial cells in vitro seems to affect signal transduction hubs downstream of the FGF receptor pathway. Altogether, these findings indicate that the loss of AIB1/SRC-3 negatively affects key drivers of wound healing along the FGF pathway.

Discussion

We show herein a previously unknown function of AIB1/SRC-3 in the control of endothelial cell phenotypes in vitro and neoangiogenesis and physiologic wound healing in vivo. Previous reports have focused predominantly on the role of this nuclear receptor coactivator in epithelial cells and have shown overexpression in a variety of cancer epithelia, including breast, prostate, colon, pancreas, and lung.1,11–15 As reported earlier, reduction of AIB1/SRC-3 in epithelial cells inhibits responses to corticosteroid hormones, insulinlike growth factor 1, epidermal growth factor, and heregulin.10,19 These pleiotropic effects are not surprising given that AIB1/SRC-3 is not only a coactivator of nuclear receptors but also a coactivator of a diverse group of other transcription factors.51 We now show that the loss of AIB1/SRC-3 in endothelial cells affects a range of endothelial-specific phenotypes, including formation of intact monolayers and tubes. Also, these in vitro observations suggest that the reduced neoangiogenesis in the Matrigel assay and during wound healing are likely due to altered endothelial cell response. This notion is supported by the data in the Matrigel neoangiogenesis experiments in AIB1/SRC-3+/− and −/− mice where exogenously added FGF2 was not able to rescue the angiogenic response in these animals. Note, however, that despite these defects in neoangiogenesis and tissue repair in adult animals described herein, AIB1/SRC-3−/− mice are viable at birth and have no discernible vascular phenotype. However, fertility and the number of offspring per birth are low. This could be due to poor uterine implantation of embryos that requires invasion into the uterine lining and the recruitment of uterine blood vessels.6,38 AIB1 is known to affect epithelial proliferation, and we observed a reduced number of proliferating keratinocytes in the wounds in AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice (see Supplemental Figure S5, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). This reduced epithelial proliferation could indirectly affect stromal cell function and provide a further mechanism of reduced wound closure and delayed reepithelialization.

Surprising to us was the fact that the wound-healing response is already maximally affected in heterozygous AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice and is not further affected by a complete loss of the AIB1/SRC-3 gene. Whereas wounds on AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice showed no differential expression of AIB1/SRC-3 mRNA over time, steady-state AIB1/SRC-3 mRNA was up-regulated in wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ mice, resulting in a fivefold expression difference at peak levels during healing. This finding suggests positive feedback of AIB1/SRC-3 expression in the injury site and a threshold expression level needed to engage physiologic repair processes in the adult. On the other hand, up-regulation of AIB1/SRC-3 in breast cancer stroma (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) may reflect a wound-healing stromal response given that there are overlapping pathways between cancer and healing wounds,24,25 and an activated wound response signature indicates poor outcome in breast cancers.52 Since loss of one AIB1/SRC-3 allele delays the development of mouse mammary tumor virus–HER2/Neu–induced tumors,9 it is tempting to speculate that similar threshold mechanisms seen in wound healing are involved in limiting the tumorigenesis, possibly due to the reduced AIB1/SRC-3 in the tumor stroma.

The dampened response of wounds in AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice was evident at different levels, including histologic findings, gene expression level, and overall metalloprotease activity. This was accompanied by reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and monocytes, to the healing wound site evidenced by the smaller rise in CD14 and CD16 inflammatory cell markers and cytokines IL-1β and CXCL2 that are produced by inflammatory cells in wounds.

Results of the functional and expression analysis suggest that major drivers in the FGF pathway53 require AIB1/SRC-3 to modulate neoangiogenesis and wound healing. FGFR1 and FGFR3 and the FGFR2b ligand FGF1050 were significantly reduced in the wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/− animals relative to +/+ controls. FGF7 and FGF10 are known to be involved in wound reepithelialization and angiogenesis37 and are typically produced by stromal cells to act predominantly on the epithelial cell FGFR2b isoform.50 The relative expression of the FGFR2b isoform was significantly lower in the wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/− mice, making this a further indicator and driver of the delay in epithelial closure. The largest change in the comparison of wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/− and control mice was the 16-fold difference in expression of the secreted FGFBP3 (Figure 5E). This secreted FGF-binding protein was shown earlier to interact with FGF1 and FGF2 and to potentiate FGF2-dependent vascular permeability and angiogenesis.46,49 Of note is that FGF pathway genes monitored in the wound-healing studies and those reported to be expressed in breast cancer stroma showed parallel changes (see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org20), suggesting these as common targets of AIB1/SRC-3 in the stromal compartment and shared drivers of healing wounds and malignancies proposed much earlier.24

Footnotes

Funded by NIH/National Cancer Institute grants CA113477 (A.T.R.) and CA71508 (A.W.), by Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program grant BC083320 (C.D.C.), and by T32 National Cancer Institute training grant CA009686 (M.A.). Flow cytometry and time lapse microscopy were performed by Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center core facilities, supported in part by cancer center support grant CA051008.

A.T.R. and A.W. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.032.

Supplementary data

AIB1 mRNA expression in the stroma of human breast cancer relative to normal breast stroma. Analysis of two published expression arrays of stromal tissues20,21 obtained from the Oncomine database (http://www.oncomine.org). Values are given as the mean ± SEM and are shown on a log2-based scale. ***P < 0.0001.

Effects of the reduction of AIB1 protein levels on endothelial cell phenotype. A: Flow cytometric analysis with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide double staining of HUVECs 48 hours after infection with a control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA. The percentage of cells in late apoptosis is indicated. B: Cell proliferation measured by crystal violet assay. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.0001 versus control. C and D: Repair of denuded endothelial monolayer areas was performed in the presence of 2 μg/mL mitomycin C. C: Representative images of denuded areas at 24 and 48 hours with the black line indicating the migration front of HUVECs. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. D: Quantitation of the closure of the denuded area. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.001 versus control.

Effects of AIB1/SRC-3 expression in fibroblasts in vitro. A: AIB1/SRC-3 overexpresssion in −/− murine embryonic fibroblasts.29 Cells were infected with lentiviral vector ± FLAG-tagged AIB1. Top: Proliferation determined using Cell Titer Glo. Bottom: Western blot (WB) for AIB1 protein and actin. B: Depletion of AIB1 from NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Proliferation of NIH3T3 cells infected with a control shRNA or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA #1 or #2. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of two independent experiments, performed in triplicate. C–F: Effects of depletion of AIB1/SRC-3 protein from Hs-27 cells. C: Western blot analysis for AIB1 and actin 48 hours after infection. The data are representative of two experiments. D: Proliferation of Hs-27 cells. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. E: Migration of Hs-27 cells after wounding of a confluent monolayer. Representative microphotographs at different times. The white line represents the migration front of the cells. F: Closure of the denuded area. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.0001 versus control (analysis of variance).

CD31 and CD14 mRNA expression in Matrigel plugs. Quantitation of CD31 and CD14 mRNA by quantitative real-time PCR of mRNA prepared from Matrigel plugs 3 to 7 days after implantation. Values were normalized to CD31 or CD14 expression levels in the plugs on day 3. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype).

Histologic analysis of wounds. A: PCNA immunostaining of proliferating keratinocytes in the hyperproliferative epithelium (he) of skin wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice on day 4 after wounding. Dotted lines depict the delimitation between the he and the granulation tissue (g). Scale bars: 0.2 mm. B: Quantitation of PCNA-positive nuclei. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per group). **P < 0.001 versus control. C: Immunohistochemical staining for AIB1/SRC-3 protein in mouse skin tissue sections and wound granulation tissue from +/+, +/−, and −/− mice. Scale bars: 0.2 mm (top); 0.1 mm (bottom). D: Representative H&E-stained sections of excisional skin wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice at different times after wounding (4, 6, and 8 days). Magnified areas shown on the right are indicated. Scale bars: 0.2 mm. s, scab; e, epithelium; n, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; g, granulation tissue; asterisks denote fibrin clots; arrowheads point to capillaries.

Wound healing in transplanted skin from and to AIB/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice. Full-thickness skin grafts from +/+ and +/− mice (donors) were grafted onto the backs of +/+ (A) and +/− (B) mice (recipients), respectively. Day 9 after grafting, a dermal biopsy punch (3-mm diameter) was used to generate full-thickness skin wounds through the center of the grafted skin in anesthetized animals (3 to 4 months old), and they were left to heal. Representative images of the grafts and wounds on day 3 are shown. Open wound areas were quantified daily for 5 days. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of the wound area (n = 3 animals per genotype). ***P < 0.0001 +/+ versus +/−.

AIB1 mRNA expression in skin wounds. Quantitative RT-PCR for AIB1 in skin wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ or +/− mice 0 to 4 days after wounding. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype).

MMP activity in wounds. Quantitation of the fluorescence signal of MMP activatable fluorescence agent measured in wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice 2 to 6 days after wounding. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 animals per group).

Expression of angiogenesis-related genes in day 4 wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ versus +/− mice. Confirmatory analysis of a gene expression survey in day 4 wounds using the mouse angiogenesis RT2 Profiler PCR array. Quantitative real-time PCR results relative to actin are shown. *P < 0.05 comparing wounds across genotypes.

Expression ratio of FGFR b and c splice isoforms in day 4 wounds of mice. mRNA expression of the b and c isoforms of FGFR1 to FGFR3 was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. The ratio of the b/c isoforms is shown. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype). *P < 0.05.

Effects of the reduction of AIB1 protein levels on FGF2-induced signaling of endothelial cells. HUVECs were transduced with shRNAs for either control or AIB1/SRC-3, and nontransduced cells were eliminated by 2 mg/mL puromycin treatment. After 4 hours of growth factor depletion in endothelial basal medium-2, cells were stimulated with or without 10 ng/mL FGF-2 for 10 minutes, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. Densitometry values were normalized to no FGF treatment for each shRNA treatment.

References

- 1.Anzick S.L., Kononen J., Walker R.L., Azorsa D.O., Tanner M.M., Guan X.Y., Sauter G., Kallioniemi O.P., Trent J.M., Meltzer P.S. AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1997;277:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louie M.C., Zou J.X., Rabinovich A., Chen H.W. ACTR/AIB1 functions as an E2F1 coactivator to promote breast cancer cell proliferation and antiestrogen resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5157–5171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5157-5171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan J., Yu C.T., Ozen M., Ittmann M., Tsai S.Y., Tsai M.J. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 and activator protein-1 coordinately regulate the transcription of components of the insulin-like growth factor/AKT signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11039–11046. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu R.C., Qin J., Hashimoto Y., Wong J., Xu J., Tsai S.Y., Tsai M.J., O'Malley B.W. Regulation of SRC-3 (pCIP/ACTR/AIB-1/RAC-3/TRAM-1) coactivator activity by I kappa B kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3549–3561. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3549-3561.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arimura A., vn Peer M., Schroder A.J., Rothman P.B. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP (NCoA-3) is up-regulated by STAT6 and serves as a positive regulator of transcriptional activation by STAT6. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31105–31112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z., Rose D.W., Hermanson O., Liu F., Herman T., Wu W., Szeto D., Gleiberman A., Krones A., Pratt K., Rosenfeld R., Glass C.K., Rosenfeld M.G. Regulation of somatic growth by the p160 coactivator p/CIP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13549–13554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260463097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh A., List H.J., Reiter R., Mani A., Zhang Y., Gehan E., Wellstein A., Riegel A.T. The nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 mediates insulin-like growth factor I-induced phenotypic changes in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8299–8308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahusen T., Fereshteh M., Oh A., Wellstein A., Riegel A.T. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and signaling controlled by a nuclear receptor coactivator, amplified in breast cancer 1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7256–7265. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fereshteh M.P., Tilli M.T., Kim S.E., Xu J., O'Malley B.W., Wellstein A., Furth P.A., Riegel A.T. The nuclear receptor coactivator amplified in breast cancer-1 is required for Neu (ErbB2/HER2) activation, signaling, and mammary tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3697–3706. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahusen T., Henke R.T., Kagan B.L., Wellstein A., Riegel A.T. The role and regulation of the nuclear receptor co-activator AIB1 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:225–237. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0405-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henke R.T., Haddad B.R., Kim S.E., Rone J.D., Mani A., Jessup J.M., Wellstein A., Maitra A., Riegel A.T. Overexpression of the nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) during progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6134–6142. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita Y., Sakakura C., Shimomura K., Nakanishi M., Yasuoka R., Aragane H., Hagiwara A., Abe T., Inazawa J., Yamagishi H. Chromosome arm 20q gains and other genomic alterations in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, as analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1857–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll R.S., Brown M., Zhang J., DiRenzo J., De Mora J.F., Black P.M. Expression of a subset of steroid receptor cofactors is associated with progesterone receptor expression in meningiomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3570–3575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakakura C., Hagiwara A., Yasuoka R., Fujita Y., Nakanishi M., Masuda K., Kimura A., Nakamura Y., Inazawa J., Abe T., Yamagishi H. Amplification and over-expression of the AIB1 nuclear receptor co- activator gene in primary gastric cancers. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie D., Sham J.S., Zeng W.F., Lin H.L., Bi J., Che L.H., Hu L., Zeng Y.X., Guan X.Y. Correlation of AIB1 overexpression with advanced clinical stage of human colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tilli M.T., Reiter R., Oh A.S., Henke R.T., McDonnell K., Gallicano G.I., Furth P.A., Riegel A.T. Overexpression of an N-terminally truncated isoform of the nuclear receptor coactivator amplified in breast cancer 1 leads to altered proliferation of mammary epithelial cells in transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:644–656. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres-Arzayus M.I., De Mora J.F., Yuan J., Vazquez F., Bronson R., Rue M., Sellers W.R., Brown M. High tumor incidence and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1 as an oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuang S.Q., Liao L., Wang S., Medina D., O'Malley B.W., Xu J. Mice lacking the amplified in breast cancer 1/steroid receptor coactivator-3 are resistant to chemical carcinogen-induced mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7993–8002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu J., Wu R.C., O'Malley B.W. Normal and cancer-related functions of the p160 steroid receptor co-activator (SRC) family. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:615–630. doi: 10.1038/nrc2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finak G., Bertos N., Pepin F., Sadekova S., Souleimanova M., Zhao H., Chen H., Omeroglu G., Meterissian S., Omeroglu A., Hallett M., Park M. Stromal gene expression predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2008;14:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nm1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnoub A.E., Dash A.B., Vo A.P., Sullivan A., Brooks M.W., Bell G.W., Richardson A.L., Polyak K., Tubo R., Weinberg R.A. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying H., Willingham M.C., Cheng S.Y. The steroid receptor coactivator-3 is a tumor promoter in a mouse model of thyroid cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:823–830. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schäfer M., Werner S. Cancer as an overhealing wound: an old hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:628–638. doi: 10.1038/nrm2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virchow R.L.K. Verlag August Hirschwald; Berlin: 1863. Vierte Vorlesung: Aetiologie der Neoplastischen Geschwülste; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dvorak H.F. Tumors: wounds that do not heal: similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin P. Wound healing: aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yancopoulos G.D., Davis S., Gale N.W., Rudge J.S., Wiegand S.J., Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmeliet P., Jain R.K. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh A.S., Lahusen J.T., Chien C.D., Fereshteh M.P., Zhang X., Dakshanamurthy S., Xu J., Kagan B.L., Wellstein A., Riegel A.T. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the nuclear receptor coactivator AIB1/SRC-3 is enhanced by Abl kinase and is required for its activity in cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6580–6593. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00118-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarbassov D.D., Ali S.M., Sabatini D.M. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moffat J., Grueneberg D.A., Yang X., Kim S.Y., Kloepfer A.M., Hinkle G., Piqani B., Eisenhaure T.M., Luo B., Grenier J.K., Carpenter A.E., Foo S.Y., Stewart S.A., Stockwell B.R., Hacohen N., Hahn W.C., Lander E.S., Sabatini D.M., Root D.E. A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell. 2006;124:1283–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan D.A., Kawahara T.L., Sutphin P.D., Chang H.Y., Chi J.T., Giaccia A.J. Tumor vasculature is regulated by PHD2-mediated angiogenesis and bone marrow-derived cell recruitment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stylianou D.C., Auf der Maur A., Kodack D.P., Henke R.T., Hohn S., Toretsky J.A., Riegel A.T., Wellstein A. Effect of single-chain antibody targeting of the ligand-binding domain in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase receptor. Oncogene. 2009;28:3296–3306. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wellstein A. AAAS; Washington, DC: 2010. Real-Time, Label-Free Monitoring of Cells in Cancer Research. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tassi E., Mcdonnell K., Gibby K.A., Tilan J.U., Kim S.E., Kodack D.P., Schmidt M.O., Sharif G.M., Wilcox C.S., Welch W.J., Gallicano G.I., Johnson M.D., Riegel A.T., Wellstein A. Impact of fibroblast growth factor-binding protein-1 expression on angiogenesis and wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2220–2232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrod K.R., Cahalan M.D. Murine skin transplantation. J Vis Exp. 2008 doi: 10.3791/634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; pii:634

- 37.Gurtner G.C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., Longaker M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu J., Liao L., Ning G., Yoshida-Komiya H., Deng C., O'Malley B.W. The steroid receptor coactivator SRC-3 (p/CIP/RAC3/AIB1/ACTR/TRAM-1) is required for normal growth, puberty, female reproductive function, and mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6379–6384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120166297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eming S.A., Krieg T., Davidson J.M. Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:514–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schultz G.S., Wysocki A. Interactions between extracellular matrix and growth factors in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Page-McCaw A., Ewald A.J., Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reiter R., Wellstein A., Riegel A.T. An isoform of the coactivator AIB1 that increases hormone and growth factor sensitivity is overexpressed in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39736–39741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czubayko F., Liaudet-Coopman E.D., Aigner A., Tuveson A.T., Berchem G.J., Wellstein A. A secreted FGF-binding protein can serve as the angiogenic switch in human cancer. Nat Med. 1997;3:1137–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibby K.A., McDonnell K., Schmidt M.O., Wellstein A. A distinct role for secreted fibroblast growth factor-binding proteins in development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8585–8590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810952106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Werner S. A novel enhancer of the wound healing process the fibroblast growth factor-binding protein. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2144–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonnell K., Bowden E.T., Cabal-Manzano R., Hoxter B., Riegel A.T., Wellstein A. Vascular leakage in chick embryos after expression of a secreted binding protein for fibroblast growth factors. Lab Invest. 2005;85:747–755. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tassi E., Henke R.T., Bowden E.T., Swift M.R., Kodack D.P., Kuo A.H., Maitra A., Wellstein A. Expression of a fibroblast growth factor-binding protein during the development of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and colon. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1191–1198. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abuharbeid S., Czubayko F., Aigner A. The fibroblast growth factor-binding protein FGF-BP. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1463–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang W., Chen Y., Swift M.R., Tassi E., Stylianou D.C., Gibby K.A., Riegel A.T., Wellstein A. Effect of FGF-binding protein 3 on vascular permeability. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28329–28337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802144200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang X., Ibrahimi O.A., Olsen S.K., Umemori H., Mohammadi M., Ornitz D.M. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family: the complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15694–15700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601252200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.York B., O'Malley B.W. Steroid receptor coactivator (SRC) family: masters of systems biology. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38743–38750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.193367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan C., Oh D.S., Wessels L., Weigelt B., Nuyten D.S.A., Nobel A.B., Van't Veer L.J., Perou C.M. Concordance among gene-expression-based predictors for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:560–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Presta M., Dell'Era P., Mitola S., Moroni E., Ronca R., Rusnati M. Fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor system in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:159–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AIB1 mRNA expression in the stroma of human breast cancer relative to normal breast stroma. Analysis of two published expression arrays of stromal tissues20,21 obtained from the Oncomine database (http://www.oncomine.org). Values are given as the mean ± SEM and are shown on a log2-based scale. ***P < 0.0001.

Effects of the reduction of AIB1 protein levels on endothelial cell phenotype. A: Flow cytometric analysis with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide double staining of HUVECs 48 hours after infection with a control or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA. The percentage of cells in late apoptosis is indicated. B: Cell proliferation measured by crystal violet assay. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.0001 versus control. C and D: Repair of denuded endothelial monolayer areas was performed in the presence of 2 μg/mL mitomycin C. C: Representative images of denuded areas at 24 and 48 hours with the black line indicating the migration front of HUVECs. Scale bar = 0.1 mm. D: Quantitation of the closure of the denuded area. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.001 versus control.

Effects of AIB1/SRC-3 expression in fibroblasts in vitro. A: AIB1/SRC-3 overexpresssion in −/− murine embryonic fibroblasts.29 Cells were infected with lentiviral vector ± FLAG-tagged AIB1. Top: Proliferation determined using Cell Titer Glo. Bottom: Western blot (WB) for AIB1 protein and actin. B: Depletion of AIB1 from NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Proliferation of NIH3T3 cells infected with a control shRNA or AIB1/SRC-3 shRNA #1 or #2. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of two independent experiments, performed in triplicate. C–F: Effects of depletion of AIB1/SRC-3 protein from Hs-27 cells. C: Western blot analysis for AIB1 and actin 48 hours after infection. The data are representative of two experiments. D: Proliferation of Hs-27 cells. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. E: Migration of Hs-27 cells after wounding of a confluent monolayer. Representative microphotographs at different times. The white line represents the migration front of the cells. F: Closure of the denuded area. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of one of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.0001 versus control (analysis of variance).

CD31 and CD14 mRNA expression in Matrigel plugs. Quantitation of CD31 and CD14 mRNA by quantitative real-time PCR of mRNA prepared from Matrigel plugs 3 to 7 days after implantation. Values were normalized to CD31 or CD14 expression levels in the plugs on day 3. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype).

Histologic analysis of wounds. A: PCNA immunostaining of proliferating keratinocytes in the hyperproliferative epithelium (he) of skin wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice on day 4 after wounding. Dotted lines depict the delimitation between the he and the granulation tissue (g). Scale bars: 0.2 mm. B: Quantitation of PCNA-positive nuclei. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per group). **P < 0.001 versus control. C: Immunohistochemical staining for AIB1/SRC-3 protein in mouse skin tissue sections and wound granulation tissue from +/+, +/−, and −/− mice. Scale bars: 0.2 mm (top); 0.1 mm (bottom). D: Representative H&E-stained sections of excisional skin wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice at different times after wounding (4, 6, and 8 days). Magnified areas shown on the right are indicated. Scale bars: 0.2 mm. s, scab; e, epithelium; n, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; g, granulation tissue; asterisks denote fibrin clots; arrowheads point to capillaries.

Wound healing in transplanted skin from and to AIB/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice. Full-thickness skin grafts from +/+ and +/− mice (donors) were grafted onto the backs of +/+ (A) and +/− (B) mice (recipients), respectively. Day 9 after grafting, a dermal biopsy punch (3-mm diameter) was used to generate full-thickness skin wounds through the center of the grafted skin in anesthetized animals (3 to 4 months old), and they were left to heal. Representative images of the grafts and wounds on day 3 are shown. Open wound areas were quantified daily for 5 days. Values are given as the mean ± SEM of the wound area (n = 3 animals per genotype). ***P < 0.0001 +/+ versus +/−.

AIB1 mRNA expression in skin wounds. Quantitative RT-PCR for AIB1 in skin wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ or +/− mice 0 to 4 days after wounding. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype).

MMP activity in wounds. Quantitation of the fluorescence signal of MMP activatable fluorescence agent measured in wounds from AIB1/SRC-3+/+ and +/− mice 2 to 6 days after wounding. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 animals per group).

Expression of angiogenesis-related genes in day 4 wounds of AIB1/SRC-3+/+ versus +/− mice. Confirmatory analysis of a gene expression survey in day 4 wounds using the mouse angiogenesis RT2 Profiler PCR array. Quantitative real-time PCR results relative to actin are shown. *P < 0.05 comparing wounds across genotypes.

Expression ratio of FGFR b and c splice isoforms in day 4 wounds of mice. mRNA expression of the b and c isoforms of FGFR1 to FGFR3 was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. The ratio of the b/c isoforms is shown. Values are given as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 animals per time point and genotype). *P < 0.05.

Effects of the reduction of AIB1 protein levels on FGF2-induced signaling of endothelial cells. HUVECs were transduced with shRNAs for either control or AIB1/SRC-3, and nontransduced cells were eliminated by 2 mg/mL puromycin treatment. After 4 hours of growth factor depletion in endothelial basal medium-2, cells were stimulated with or without 10 ng/mL FGF-2 for 10 minutes, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. Densitometry values were normalized to no FGF treatment for each shRNA treatment.