Abstract

Auditory nerve fibers are the major source of excitation to the three groups of principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN), bushy, T stellate, and octopus cells. Shock-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) in slices from mice showed systematic differences between groups of principal cells, indicating that target cells contribute to determining pre- and postsynaptic properties of synapses from spiral ganglion cells. Bushy cells likely to be small spherical bushy cells receive no more than three, most often two, excitatory inputs; those likely to be globular bushy cells receive at least four, most likely five, inputs. T stellate cells receive 6.5 inputs. Octopus cells receive >60 inputs. The N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) components of eEPSCs were largest in T stellate, smaller in bushy, and smallest in octopus cells, and they were larger in neurons from younger than older mice. The average AMPA conductance of a unitary input is 22 ± 15 nS in both groups of bushy cells, <1.5 nS in octopus cells, and 4.6 ± 3 nS in T stellate cells. Sensitivity to philanthotoxin (PhTX) and rectification in the intracellular presence of spermine indicate that AMPA receptors that mediate eEPSCs in T stellate cells contain more GluR2 subunits than those in bushy and octopus cells. The AMPA components of eEPSCs were briefer in bushy (0.5 ms half-width) than in T stellate and octopus cells (0.8–0.9 ms half-width). Widening of eEPSCs in the presence of cyclothiazide (CTZ) indicates that desensitization shortens eEPSCs. CTZ-insensitive synaptic depression of the AMPA components was greater in bushy and octopus than in T stellate cells.

INTRODUCTION

The demands made on synapses in the early stages of the mammalian auditory pathway are extraordinary. Auditory nerve fibers and their targets in the brain stem convey sensory information in the timing and in the rate of firing, requiring synapses to transmit with temporal precision. Furthermore, because the different groups of target neurons of auditory nerve fibers perform different integrative tasks, the demands made on synapses are not uniform.

Principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN) carry out a variety of integrative tasks. Bushy cells encode the fine structure of sounds; they encode the timing of individual cycles of sound pressure waves at low frequencies and the envelopes of high-frequency sounds with a temporal precision of 700 μs (Joris et al. 1994a,b). Bushy cells comprise subpopulations with distinct Nissl staining patterns that occupy different parts of the VCN and differ in their central projections (Cant and Casseday 1986; Cant and Morest 1979b; Harrison and Irving 1966; Osen 1969; Smith et al. 1991, 1993; Tolbert and Morest 1982b; Tolbert et al. 1982). In mice, most bushy cells are small spherical (bushy-s) or globular (bushy-g) because, like other small mammals that lack low-frequency hearing, mice have few large spherical bushy cells and a small medial superior olive (Willard and Ryugo 1983). Octopus cells signal the presence of broadband transients by detecting the coincident firing of populations of auditory nerve fibers. They do so with a temporal precision of ∼200 μs (Oertel et al. 2000). T stellate cells monitor the spectrum of sounds with individual cells signaling the rise and fall of energy over a small range of frequencies by firing tonically throughout the duration of a sound (Blackburn and Sachs 1990; Frisina et al. 1990). Stellate cells compensate for adaptation in the firing of a few auditory nerve fibers but in so doing obscure information about the fine structure of sounds (Blackburn and Sachs 1989, 1990; Ferragamo et al. 1998). In this study, we examine features of synaptic excitation in the principal cells of the mammalian VCN that enable these cells to perform these tasks. Convergence of fibers can remove temporal jitter by averaging, but it can also broaden tuning and obscure fine structure. The time course of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs), synaptic depression, the calcium permeability of AMPA receptors, and the presence of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors affect the ability of sensory information to be transmitted to the principal cells.

Myelinated auditory nerve fibers supply the excitation that drives responses to sound in the principal cells of the VCN. They enter the brain stem and bifurcate in the nerve root, innervating bushy and a few T stellate cells through the ascending branch, and mainly T stellate and octopus cells through the descending branch (Brown and Ledwith 1990; Fekete et al. 1984; Liberman 1991, 1993). Bushy cells receive much input from auditory nerve fibers through large terminals, the end bulbs of Held, at the soma; although some inputs do arise on the bush of short dendrites, there is little evidence of dendritic filtering (Cant and Morest 1979a; Gardner et al. 1999; Gomez-Nieto and Rubio 2009; Sento and Ryugo 1989). Octopus cells receive most of their input along the dendrites. The correlation between rise and decay time and rise time and amplitude of miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) indicates that dendritic filtering occurs in octopus cells, but the correlation is small, presumably because the thickness of the dendrites makes octopus cells relatively electrically compact (Gardner et al. 1999). T stellate cells have thinner dendrites and in cats receive little input from myelinated auditory nerve fibers at the soma (Cant 1981). The positive correlation between rise and decay times of mEPSCs indicates that dendritic filtering occurs in T stellate cells (Gardner et al. 1999).

How synaptic currents evoke firing also depends on how the voltage-gated conductances of neurons shape synaptic currents to voltage changes. The biophysical properties of the principal cells of the VCN are so distinct that they serve as the basis for their identification in mice and in other species. Bushy cells are characterized by having shorter time constants in the depolarizing than in the hyperpolarizing voltage range. A hyperpolarization-activated conductance reduces the input resistance at rest and a low voltage–activated K+ conductance that is strongly and quickly activated near the resting potential produces rectification and prevents repetitive firing (Cao et al. 2007; Manis and Marx 1991; Rothman and Manis 2003). These conductances make bushy cells sensitive to the rate of depolarization (McGinley and Oertel 2006). Octopus cells express these same voltage-sensitive conductances at higher levels, giving them even lower input resistances and the ability to respond to depolarization with only a single action potential (Bal and Oertel 2000, 2001; Bal et al. 2009; Golding et al. 1999; Oertel et al. 2000). To reach the firing threshold, octopus and bushy cells require that depolarizations rise above a threshold rate (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002; McGinley and Oertel 2006). T stellate cells fire regular action potentials as a function of how strongly they are depolarized (Ferragamo et al. 1998; Oertel et al. 1990). They lack low voltage–activated K+ conductances and their hyperpolarization-activated conductances are not strongly activated near rest (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006).

In this study, we stimulated excitatory inputs with shocks and used measurements of EPSCs to estimate how many inputs principal cells receive to compare the time courses of eEPSCs, to determine what types of receptors are activated, and to compare short-term plasticity in these cells. The findings show that subpopulations of bushy cells differ in the number of inputs and provide insight into how each of the groups of principal cells carries out its separate integrative task.

METHODS

Preparation of slices

Recordings were made from coronal slices of the cochlear nuclei from ICR mice. For most experiments, mice were between 17 and 19 days old; in one series of experiments concerning glutamate receptors, mice were between 8 and 19 days old. Slices, 220 μm thick, were cut with a vibrating microtome (Leica VT 1000S) in normal physiological saline at 24–27°C and transferred to a recording chamber (∼0.6 ml) and superfused continually at 5–6 ml/min. The temperature was measured in the recording chamber, between the inflow of the chamber and the tissue, with a Thermalert thermometer (Physitemp), the input of which comes from a small thermistor (IT-23, Physitemp, diameter: 0.1 mm). The output of the Thermalert thermometer was fed into a custom-made, feedback-controlled heater that heated the saline in glass tubing (1.5 mm) just before it reached the chamber to maintain the temperature at 33°C. The tissue was visualized through a compound microscope (Zeiss Axioskop) with a 63× water immersion objective and CCD Camera (Hamamatsu) with the image displayed on a screen.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings were made using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA). Patch electrodes whose resistances ranged between 3.8 and 7 MΩ were made from borosilicate glass. All recordings of evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) were digitized at 40 kHz and low-pass filtered at 10 kHz. The series resistance in 101 recordings, 12.3 ± 2.1 MΩ, was compensated by 85–90% in recordings from octopus cells and by 70–80% in recordings from T stellate and bushy cells with a 10-μs lag. EPSCs were evoked by shocks through a Master-8 stimulator and Iso-flex isolator (AMPI, Jerusalem, Israel), delivered through an extracellular saline-filled glass pipette (∼5 μm tip).

Solutions

The extracellular physiological saline comprised (in mM) 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 20 NaHCO3, 3 HEPES, and 10 glucose, saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.3–7.4, between 24 and 33°C. The osmolality was 309 mOsm/kg (3D3 Osmometer, Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA). All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich, unless stated otherwise. Measurements of EPSCs were made in the presence of 1 μM strychnine to block inhibition. To separate currents mediated through AMPA receptors from those mediated through NMDA receptors, 100 μM d-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (APV) was added. In some experiments, 30 μM kainate and 50 μM philanthotoxin (PhTX) were added to the extracellular saline solution.

Recording pipettes were generally filled with a solution that consisted of (in mM) 90 Cs2SO4, 20 CsCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 GTP, 5 Na-phosphocreatine, and 5 mM QX314 and was adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH (∼298 mOsm). The final holding potentials were corrected for a −10 mV junction potential. Some recordings were made with pipettes that contained 100 μM spermine. To correlate biophysical properties with the number of steps in inputs, one series of recordings was made with pipettes that contained (in mM) 108 potassium gluconate, 9 HEPES, 9 EGTA, 4.5 MgCl2, 14 phosphocreatinine (tris salt), 4 ATP (Na salt), and 0.3 GTP (tris salt), whose pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH and that had a final osmolarity 297 mOsm/kg.

Data analysis

Analysis of EPSCs was performed by using pClamp (Clampfit 9.0, Axon Instruments). K-means cluster analysis was performed by Unscrambler 9.8 (CAMO Support Team). All statistical tests were performed on Origin version 7.5 software and are given as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Serial recruitment provides estimate of the number and size of converging inputs

Auditory nerve fibers are the major source of excitation in all three groups of principal cells of the VCN, T stellate, octopus, and bushy cells, but these groups differ in the number of auditory nerve fibers that converge on them. To measure convergence, we recorded synaptic currents as inputs were serially recruited by shocks of increasing strength to the fascicles of fibers in the vicinity of the recorded cell. Auditory nerve fiber inputs are recruited in an all-or-none manner, and their recruitment is evident in the postsynaptic cell as a step in the size of the eEPSC.

We identified principal cells by where they lay, by how they responded to current and voltage pulses with previously established criteria that remained distinctive even with Cs+ in the pipette. Bushy-s cells are most common anterior to the nerve root; bushy-g cells are most common within or near the nerve root. Both fire transiently when they are depolarized and show strong rectification before a hyperpolarizing sag develops in response to hyperpolarizing current pulses (Cao et al. 2007). T stellate cells are most common posterior to the nerve root, have relatively high-input resistances, and are characterized by their tonic firing in response to depolarizing current (Ferragamo et al. 1998; Fujino and Oertel 2001; Oertel et al. 1990; Rodrigues and Oertel 2006). Octopus cells lie at the most caudal and dorsal pole of the VCN and are characterized by their low input resistances and by their firing of a small action potential only at the onset of a depolarization and at the offset of a hyperpolarization (Golding et al. 1995).

In T stellate cells, shocks to nearby fibers evoked EPSCs ∼2 ms in duration that grew in jumps as the strength of shocks was increased in small increments. A superposition of traces at every other stimulation voltage shows clumps of similarly shaped EPSCs in a T stellate cell (Fig. 1A). The short and consistent synaptic delays indicate that synaptic responses are monosynaptic. The plot of peak currents as a function of the shock strength also shows the stepwise growth of EPSCs (Fig. 1B). The dashed lines in the plot indicate the mean of each cluster, determined by K-means cluster analysis, and provide a functional estimate of the number of inputs. ANOVA on the resultant clusters showed that in each case the clusters differed significantly (P < 0.001). We estimate that this T stellate cell had five excitatory inputs, each contributing between ∼0.2 and 0.5 nA; the maximal amplitude of synaptic currents was a little more than 2 nA. This estimate of the number of excitatory inputs is a lower limit for three reasons. First, it is possible that small inputs are unresolved. Second, if several auditory nerve fibers that innervate the T stellate cell lie close together, they might have similar thresholds to shocks and thus might have been recruited together. Third, some axons and terminals could have escaped stimulation. Similar measurements in 11 T stellate cells showed that, on average, eEPSCs in T stellate cells grew in 6.5 ± 1.0 (n = 11) steps. The number of inputs estimated in these experiments under voltage clamp with stimulation of fiber fascicles is similar to a previous estimate in sharp electrode recordings of EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the nerve root, 5.0 ± 0.8 (n = 4) (Ferragamo et al. 1998). The small difference between these measurements may reflect excitatory inputs from other T stellate cells, which are more likely to have been stimulated by shocks to fiber fascicles within the nucleus than by shocks to the nerve root (Ferragamo et al. 1998; Oertel et al. 1990). We conclude that T stellate cells receive input from about five or six auditory nerve fibers.

Fig. 1.

In T stellate cells, shocks to fiber bundles in the vicinity of the recorded cell body evoked excitatory postsynatic currents (EPSCs) that grew in steps with the strength of the shock. A: whole cell patch-clamp recording from a T stellate cell whose voltage was clamped at −65 mV. The artifact marks when shocks of 0.1 ms duration and variable voltage were presented. After a delay of ∼0.5 ms, an inward current was detected in the T stellate cell whose amplitude grew with the strength of shocks. Superposition of the traces indicates that the amplitude of EPSCs clustered. B: the plot of the peak amplitude of EPSCs shown in A as a function of shock strength also shows that the magnitude of EPSCs grew in steps. The dashed lines show means of each cluster determined by K-means cluster analysis. A step in the amplitude of EPSCs reflects the recruitment of at least 1 fiber and is the basis for estimating the number of excitatory inputs of the recorded cell. C: the amplitude distribution of steps in all T stellate cells (n = 11) from which measurements were made reflects the contribution of a single fiber to the synaptic current at −65 mV. The histogram is unimodal with a peak ∼0.25 nA.

The amplitude of steps in eEPSCs in T stellate cells was on average 0.3 ± 0.2 nA (n = 38) at −65 mVand had a unimodal distribution. Figure 1C shows that the amplitudes of inputs averaged over the population of T stellate cells peaked at 0.2 nA. [These currents are smaller than those reported by Chanda and Xu-Friedman (2010), probably because of the difference in the electrochemical gradient for Na+.] As eEPSCs reversed at ∼0 mV (see Fig. 7), these currents corresponded to steps in conductance of 4.6 ± 3 nS.

Fig. 7.

Two tests indicate that AMPA receptors of T stellate cells contain more GluR2 subunits than those of bushy or octopus cells. A: eEPSCs were recorded at −60 mV under control conditions. Then 30 μM kainate, which activates AMPA receptors, and 50 μM PhTX, which blocks open receptors, were applied together for ∼5 min. Measurements were made in the presence of 50 μM PhTX after kainate was washed out. Traces show averages of 15 EPSCs, evoked at 0.2 Hz. There was no systematic change in amplitude in those EPSCs, suggesting that few if any additional AMPA receptors were blocked after kainate was washed out. B: in the presence of 100 μM APV, eEPSCs were recorded from the same 3 cells as A at −60 and +40 mV. C: plots of normalized, peak eEPSCs from 5 T stellate, 3 bushy-s, 3 bushy-g, and 5 octopus cells as a function of voltage show that the amplitude of EPSCs varies linearly with voltage in the hyperpolarizing voltage range but rectify in the depolarizing voltage range. The rectification arises from the block of outward current through the AMPA receptors in the intracellular presence of 100 μM spermine, applied at eEPSCs reversed near 0 mV.

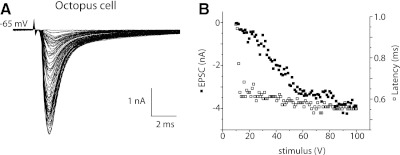

In octopus cells, also, the magnitude of synaptic currents grew with increasing shock strength, but in these cells, EPSCs grew almost continuously with few clear steps (Fig. 2, A and B). The graded growth in amplitude of EPSCs reflects the recruitment of many auditory nerve inputs, each of which provides a relatively small synaptic current, consistent with the pattern of recruitment of EPSPs with shocks to the nerve root measured with sharp electrodes (Golding et al. 1995). Over the 30-fold range of amplitudes, the time to peak varied over only ∼250 μs (Fig. 2B, open symbols). The largest step in amplitude was 0.15 nA, corresponding to ∼2 nS, but most intervals were smaller, indicating that most inputs activated <2 nS. A separate rough estimate of the conductance produced by a single input can be made from the maximal observed conductance. The VCN of a mouse contains ∼200 octopus cells (Willott and Bross 1990). Because every labeled auditory nerve fiber terminates in the octopus cell area, and mice have ∼12,000 auditory nerve fibers, octopus cells receive input from ≥60 auditory nerve fibers on average (Ehret 1979; Golding et al. 1995). The peak, synaptically evoked conductance measured in 12 octopus cells was 52 ± 14 nS, likely an underestimate because probably not all inputs were activated by the shocks. If we assume that a large proportion of an octopus cell's auditory nerve inputs was activated by the shocks, individual auditory nerve fibers would on average be expected contribute ∼1/60 of the maximal eEPSC, or ∼0.87 nS. We conclude from these two independent but rough estimates that individual auditory nerve fibers contribute <1.5 nS.

Fig. 2.

In an octopus cell, shocks to fiber bundles evoked responses that were graded. A: after a synaptic delay of 0.5 ms, shocks evoked inward currents. The amplitude of EPSCs varied almost continuously with the strength of shocks. Also, the peaks of small responses occurred ∼0.3 ms later than those of larger responses. B: a plot of the peak amplitudes of EPSCs (■) as a function of shock strength. The plot of amplitudes of EPSCs confirms that responses varied almost continuously in size. The largest jump was 0.15 nA. The plot of latency to peak (□) as a function of shock strength shows that over a wide range of stimulus strengths and response amplitudes, the latency varied only within ∼0.250 ms.

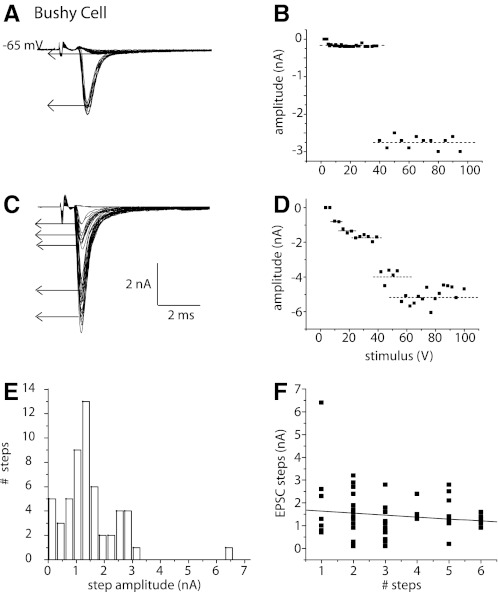

Bushy cells have eEPSCs whose amplitude grows in discrete steps, indicating that they receive excitatory input from a relatively small number of fibers. The short and consistent synaptic delays indicate that synaptic responses are monosynaptic; we have not observed EPSCs with longer latencies that could have arisen disynaptically. Figure 3 shows responses to shocks of varying strength in two bushy cells. The traces show that when the strength of shocks was increased in small increments the sizes of EPSCs grew in steps (Fig. 3, A and C). In plots of EPSCs as a function of stimulus strength, the steps were identified by K-means cluster analysis (Fig. 3, B and D, dashed lines). The EPSCs of the bushy cell shown in Fig. 3, A and B, grew in two steps, whereas those of the bushy cell shown in Fig. 3, C and D, grew in more steps and reached a larger maximal value.

Fig. 3.

In bushy cells, EPSCs grew in steps with 2 patterns. A: EPSCs in a bushy cell that was held at −65 mV grew in 2 steps, the 1st being small and the 2nd being large. B: a plot of the amplitudes of EPSCs as a function of shock strength also shows the steps. K-means cluster analysis indicated that the response grew in 2 steps. The 1st step was smaller (0.4 nA) than the 2nd (1.4 nA). C: in a different bushy cell, EPSCs grew in more steps and reached a larger maximal value. D: a plot of the growth of EPSCs as a function of shock strength reflects the presence of multiple steps. K-means cluster analysis indicates that EPSCs grew in 5 steps in this cell. E: the distribution of amplitudes of steps in EPSCs over the entire population of bushy cells from which such recordings were made (n = 30) shows that the sizes of steps were multimodal. F: there was little or no correlation between the sizes and total number of steps in bushy cells. Sizes of steps were ∼1.5 nA independent of the estimated number of inputs.

The variability in the magnitude of jumps in the eEPSC raised the question whether those jumps might reflect different types of inputs. Might a population of large jumps represent inputs through end bulbs and smaller jumps reflect input through ordinary synaptic terminals? The amplitude distribution of current steps measured in the population of recorded bushy cells reflects the variability (Fig. 3E). The magnitude of current jumps in the combined subpopulations of bushy cells varied over a 30-fold range, between 0.3 and 6.6 nA. The distribution of amplitudes was multimodal, with one peak at 0.3 nA, another at 1.5 nA, a third at 2.7 nA, and a single point at 6.5 nA. Because the reversal potential of eEPSCs is ∼0 mV (see Fig. 7), these peaks corresponded to conductance steps of 4.6, 22, 42, and 100 nS.

If large current steps were to reflect the simultaneous recruitment of multiple inputs, the magnitude of current steps would be expected to be inversely correlated with the total number of steps. A plot of the magnitude of steps of EPSCs as a function of the total number of steps, the estimated number of excitatory inputs, is shown in Fig. 3F. This plot shows that the size of steps varied over a wide range independently of the total number of inputs and that the correlation between amplitude and maximal number of inputs is, if present, weak. The average size of steps was 1.4 ± 1 nA (n = 55) at −65 mV or ∼22 nS, independently of whether recordings were from bushy-s or bushy-g cells.

Two groups of bushy cells differ in the number of excitatory inputs

Estimates of the number of synaptic inputs in 30 bushy cells varied between two and six. Figure 4A shows that the number of steps in bushy cells is bimodally distributed. About 60% of the recorded bushy cells received between one and three inputs and ∼40% of recorded bushy cells received four or more inputs. Because the amplitude of steps is independent of the number of steps (Fig. 3F), on average, synaptic currents would be expected to be larger in neurons with larger numbers of inputs. Figure 4B shows that this is the case. K-means cluster analysis indicates that bushy cells fall into two groups indicated by the ovals (P < 0.05). We conclude that bushy cells fall into two subgroups: one that has no more than three inputs and another that has at least four inputs.

Fig. 4.

Bushy cells fall into 2 distinct groups; bushy cells that fire 1 action potential have more inputs than those that fire multiple action potentials. A: histogram of the estimated number of inputs of bushy cells is bimodal consistent with bushy cells falling into 2 groups. One group, 60%, received input from ≤3 inputs, whereas another group, 40%, received input from ≥4 fibers. B: the bushy cells that had most inputs tended to have the largest maximal EPSCs. K-means cluster analysis indicated that the amplitudes of maximal EPSCs fell into 2 groups indicated by the ovals (P < 0.05). C: bushy cell with 4 inputs fired a single action potential when depolarized with current. Synaptic responses to shocks that were increased in small increments showed 4 steps in rising slope and amplitude. Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) were recorded when the cell was hyperpolarized to −100 mV to increase their resolution. Under these conditions, 3 steps were subthreshold and a 4th brought the cell to threshold, giving the cell a total of at least 4 inputs. Inset: responses of the same cell to a family of current pulses from +0.6 to −0.6 nA that changed in 0.1 nA increments. The bushy cell fired only a single action potential no matter how strongly it was depolarized. D: bushy cell with 2 inputs fired 3 action potentials when depolarized with current. The slope of the foot of the EPSP in this cell grew in 2 steps as the shock strength was increased in small increments. Inset: current pulses in this bushy cell evoked 3 action potentials. The larger responses to current pulses than in C reflect a higher input resistance.

The differences in numbers of inputs were correlated with differences in location. In the course of these experiments, we discovered that bushy cells with at least four inputs were generally found in coronal slices that included the nerve root, whereas those with less than three inputs were located in more anterior slices. The correlation of the difference in location with the difference in numbers of inputs raised the question whether numbers of inputs might define subpopulations of bushy cells.

The biophysical properties of bushy cells vary and also largely fall into two groups. Bushy cells that fired one or two action potentials had lower input resistances, larger low voltage–activated K+ and hyperpolarization-activated conductances, and larger rate of depolarization thresholds (Cao et al. 2007). The question thus arose whether the biophysical properties of bushy cells are correlated with numbers of inputs. Because intracellular Cs+ alters the firing properties, a series of whole cell patch-clamp recordings was made to associate numbers of inputs with numbers of action potentials elicited by depolarization with pipettes that contained a gluconate-based solution. Shocks to the nerve evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) that grew in four steps in one bushy cell (Fig. 4C). Responses to current pulses showed that this cell fired only one action potential when it was depolarized. Shocks to another bushy cell evoked EPSPs whose slopes grew in two steps (Fig. 4D). This cell fired maximally three action potentials in response to depolarization with current. The larger responses to current pulses indicated that the input resistance of this bushy cell was higher than that shown in Fig. 4C. Such measurements were made in seven bushy cells. The synaptic responses of the three bushy cells that fired only a single action potential grew on average in 3.3 ± 0.58 steps. The smaller average number of steps measured in these experiments probably resulted from the difficulty in resolving small steps in current clamp. Synaptic responses in four bushy cells that fired more than two action potentials grew on average in 1.8 ± 0.50 steps. The two groups were statistically significantly different (P < 0.05). We conclude that bushy cells that fire only one or two action potentials have more inputs than those that fire more than two action potentials. Their location and consistency with findings in other species of suggests that the bushy cells with no more than three inputs correspond to spherical bushy cells (bushy-s) and that those with at least four inputs correspond to globular bushy cells (bushy-g).

Comparison of characteristics of eEPSCs between principal cells

Individual auditory nerve fibers have collateral branches with terminals where each of the groups of principal cells is located (Liberman 1991, 1993; Ryugo 1992). Furthermore, for each of the principal cells, auditory nerve fibers are the major source of excitatory input so that eEPSCs are likely to have arisen through auditory nerve fibers. Bushy, T stellate, and octopus cells each receive excitatory inputs from noncochlear sources but those are minor. In the VCN, we can therefore determine how functional properties of synaptic connections of one neuron, the spiral ganglion cell, differ as a function of the target cell.

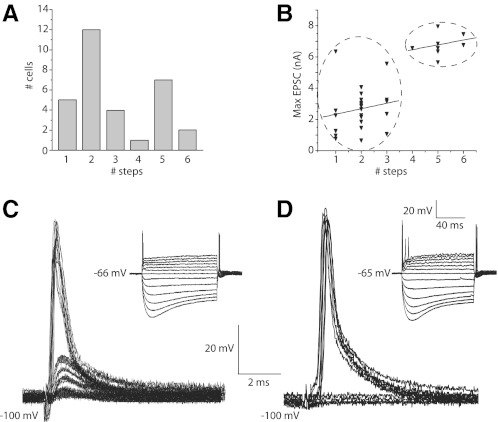

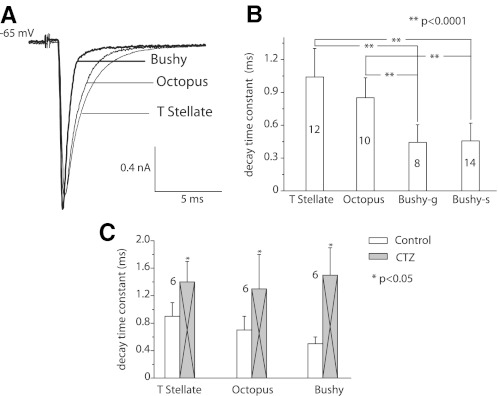

The time course of eEPSCs was more rapid in both subtypes of bushy cells than in T stellate or octopus cells (Fig. 5A). In some cells, the decay of eEPSCs was fit well with a single exponential; when the decay was fit better with double exponentials, the fast exponential dominated. The difference was not consistent between cell types, however, so for simplicity, we compared single exponential fits to the decays. Bushy cells had significantly shorter time constants of decay (0.5 ms) than T stellate or octopus cells (0.9–1 ms; P < 0.0001; Fig. 5B). There was no difference between decay time constants in bushy-s and bushy-g cells. It is possible that the voltage was not perfectly clamped in octopus cells (see Fig. 7). The eEPSC may therefore appear smaller and slower than they were. The time course of EPSCs in bushy cells matches what has been reported (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010).

Fig. 5.

The time course of eEPSCs differed between principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN). A: averages of 10 responses from a bushy-s, an octopus, and a T stellate cell of nearly equal magnitudes are superimposed. The eEPSCs from the bushy cell are narrower than those of T stellate and octopus cells, whereas those of T stellate and octopus cells are similar. B: measurements from populations of cells indicate that the differences were consistent. The decay time constants associated with single exponential fits were significantly shorter in bushy than in T stellate and octopus cells (**P < 0.0001). C: after the application of 100 μM cyclothiazide (CTZ), eEPSCs decayed more slowly, indicating that desensitization of receptors sharpens the timing of synaptic excitation. The data from bushy-s and bushy-g cells were pooled as there was no detectable difference between them.

The AMPA receptors of principal cells of the VCN desensitize (Gardner et al. 2001). Cyclothiazide (CTZ) decreases desensitization in many variants of AMPA receptors and can thus be used to assess whether desensitization contributes to shortening EPSCs (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010; Gardner et al. 2001; Partin et al. 1993). The differences in the sizes and shapes of synaptic terminals on the different groups of principal cells raised the possibility that desensitization shapes EPSCs differently. eEPSCs in all three groups of principal cells were broadened but not significantly changed in amplitude in the presence of CTZ (Fig. 5C). In octopus cells, the decay time constant was lengthened from 0.7 ± 0.2 to 1.3 ± 0.5 ms (n = 6, P < 0.05), in bushy cells it was lengthened from 0.5 ± 0.1 to 1.5 ± 0.4 ms (n = 6, P < 0.05), and in T stellate cells the decay time constant was lengthened from 0.9 ± 0.2 to 1.4 ± 0.3 ms (n = 6, P < 0.05). It has also been reported that CTZ facilitates neurotransmitter release through presynaptic mechanisms, but we saw no evidence of presynaptic actions in our measurements (Ishikawa and Takahashi 2001).

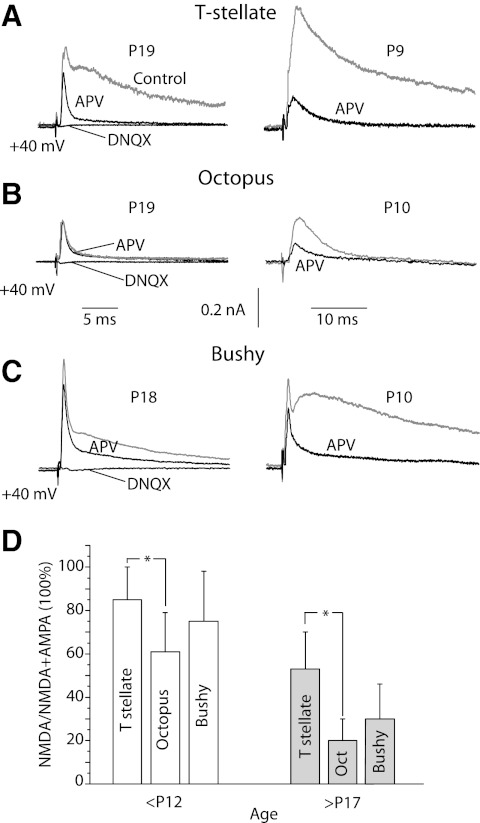

What the relative roles are of AMPA and NMDA receptors in principal cells of the VCN is not known. As the voltage was held at −65 mV in the presence of 1.3 mM extracellular Mg2+, NMDA receptors were blocked in the measurements described above (Figs. 1A, 2A, and 3, A, C, and E) (Nowak et al. 1984). The NMDA components of synaptic currents were made evident by measuring eEPSCs at +40 mV and testing their sensitivity to 100 μM APV (Fig. 6, A–C). The fast component that remained was blocked by 40 μM DNQX, confirming that it was mediated through AMPA receptors. T stellate, octopus, and bushy cells from P9 or P10 mice had eEPSCs carried largely through NMDA receptors, whereas those from mice at >P17 had more current carried through AMPA receptors and less through NMDA receptors. In both young and more mature mice, octopus cells had the smallest currents through NMDA receptors and T stellate cells had the largest (Fig. 6D). Measurements from subtypes of bushy cells were combined because there was no obvious difference between them and because the distinction between bushy-s and bushy-g cells is unclear in young animals. The ratio of the difference current recorded at +40 mV in the presence and absence of APV and the peak current in the presence of APV yielded the NMDA/total current ratio. The ratios shifted from younger to older mice in T stellate cells from 0.85 (n = 5) to 0.53 (n = 6), in octopus cells from 0.61 (n = 4) to 0.2 (n = 5), and in bushy cells from 0.75 (n = 5) to 0.3 (n = 5). The differences between octopus and T stellate cells are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

The proportion of the synaptic current that was mediated through NMDA receptors varied as a function of age and cell type. A-C: EPSCs were recorded at +40 mV in neurons from more mature mice at P18 or P19 (gray traces, left) and less mature mice (gray traces, right) in all three types of principal cells. 100 μM APV blocked the slow component of the synaptic current (dark traces). The remaining fast EPSC was blocked by 40 μM DNQX (left) D: The fraction of peak eEPSCs that is sensitive to APV was compared between cell types and in old and young mice. The difference between T stellate and bushy cells was not statistically significant but the difference between T stellate and octopus cells was (*P < 0.05). APV-sensitive currents were larger in younger than in older mice.

Are the AMPA receptors that mediate eEPSCs similar between groups of cells? We tested whether the AMPA receptors that respond to shocks of inputs contained GluR2 subunits, which are subunits that make AMPA receptors impermeable to Ca2+. Philanthotoxin 343 (PhTX) is a polyamine-containing spider toxin that blocks open, calcium-permeable AMPA receptors when cells are hyperpolarized (Mellor and Usherwood 2004). Figure 7A shows differences between groups of principal cells in their sensitivity to 50 μM PhTX. eEPSCs were initially recorded under control conditions. AMPA receptors were opened by 30 μM kainate and simultaneously exposed to 50 μM PhTX. After the kainate was washed away and in the continued presence of 50 μM PhTX, eEPSCs were recorded again. Cells were held at −60 mV throughout the experiment. eEPSCs were diminished less by PhTX in T stellate cells, 40 ± 6% (n = 4), than in bushy (85 ± 7%; n = 5) or octopus cells (74 ± 10%; n = 4), indicating that AMPA receptors of T stellate cells contain more GluR2 than those of bushy or octopus cells.

Spermine, applied through the recording pipette to the inside of cells at 100 μM, blocks outward but not inward currents through calcium permeable AMPA receptors and provides another test for the presence of GluR2 subunits. The rectification was stronger in octopus and bushy cells than in T stellate cells; rectification indices were 0.3 ± 0.1 in both subpopulations of bushy cells and octopus cells, whereas they were 0.6 ± 0.1 in T stellate cells (Fig. 7, B and C). These observations indicate that AMPA receptors of T stellate cells more commonly have GluR2 subunits than bushy or octopus cells. This conclusion was unexpected because earlier studies based on mEPSCs and the rapid application of agonist to outside-out patches had indicated that AMPA receptors were similar in all the principal cells of the VCN (Gardner et al. 1999, 2001). As the measurements of rectification depend on the ability to clamp the voltage of neurons at positive voltages, the possibility that these measurements are distorted by the imperfect control of voltage cannot be ignored. However, the tests of the sensitivity to spermine are consistent with those of the sensitivity to PhTX, which does not require clamping at depolarized potentials, so we conclude that a larger proportion of AMPA receptors that mediate eEPSCs in T stellate cells contain GluR2 than in bushy or octopus cells.

The measurements shown in Fig. 7 make possible an assessment of the quality of the voltage clamping. Several observations indicate that clamping was reasonably good for T stellate and bushy cells. First, the current-voltage relationships in the hyperpolarizing voltage range were linear in all three types of cells. Second, the reversal potentials of eEPSCs in bushy-g and bushy-s cells and in T stellate cells were at 0 mV even when the morphology of these cells differed and even when eEPSCs were considerably larger in bushy than in T stellate cells. The reversal potential of eEPSCs bushy cells is identical to that reported by others (Isaacson and Walmsley 1995b). It is possible that the voltage clamp of eEPSCs in octopus cells was imperfect. The measured reversal potential of eEPSCs in octopus cells was +10 mV and different from that in bushy and T stellate cells when the reversal potentials measured from excised patches were similar in octopus, bushy, and T stellate cells (Gardner et al. 2001).

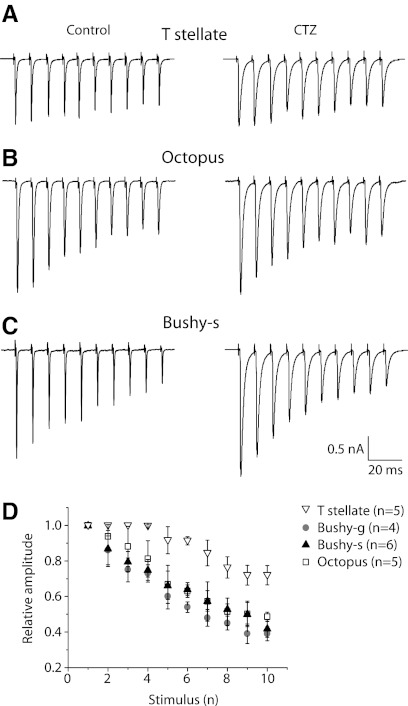

Synaptic depression is a functionally important feature of auditory synapses that differs in different types of principal cells. Responses to successive shocks delivered at 100 Hz became progressively smaller in all cell types (Fig. 8). Depression was least evident in the T stellate cell (Fig. 8A) and most evident in the octopus cell (Fig. 8C). Average rates of depression in larger samples of cells show that these differences are consistent within cell type. At 100 Hz, there was ∼25% decrement in amplitude between the 1st and 10th responses in T stellate cells but ∼50% decrement in octopus and both subtypes of bushy cells (Fig. 8D). The extent of depression increased with stimulation rate, but at every rate tested, 100–300 Hz, synaptic depression was least evident in T stellate and most evident in octopus cells, with bushy cells being intermediate. Although individual responses were lengthened slightly, the progressive decrease in eEPSCs was unaffected by CTZ at 100 Hz. At higher frequencies, CTZ slowed synaptic depression slightly, as reported by others (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010). We observed no obvious facilitatory presynaptic effects of CTZ in these responses to trains (Ishikawa and Takahashi 2001). We conclude that synaptic depression at all but the highest stimulation rates seems to be a presynaptic phenomenon in these neurons. These findings indicate that the terminals of auditory nerve fibers are not uniform in their release properties. Terminals apposed to bushy and octopus cells have higher release probabilities than those apposed to T stellate cells.

Fig. 8.

Cyclothiazide-insensitive synaptic depression was evident in EPSCs evoked by trains of shocks at 100 Hz recorded at −65 mV in all 3 types of principal cells. A: in a T stellate cell, EPSCs showed relatively little depression. B: in an octopus cell, depression was obvious. C: in a bushy-s cell, synaptic depression was also obvious. D: depression during 100 Hz trains was compared by normalizing EPSCs to the 1st EPSC of each train. The degree of synaptic depression was consistent within a cell type; depression was greater in octopus and bushy cells than in T stellate cells.

DISCUSSION

Measurements of EPSCs in principal cells of the VCN provide two insights. First, the functional properties of synapses between auditory nerve fibers and their targets differ as a function of the target neuron not only in postsynaptic but also presynaptic features. Some synapses are well suited for transmitting phasic features of sounds such as onset transients and phase and others for transmitting tonic features of sounds such as their envelope and their spectrum. Second, bushy cells in mice fall into two groups that differ in the number of converging excitatory inputs, likely corresponding to small spherical and globular bushy cells.

Synaptic output from type I auditory nerve fibers

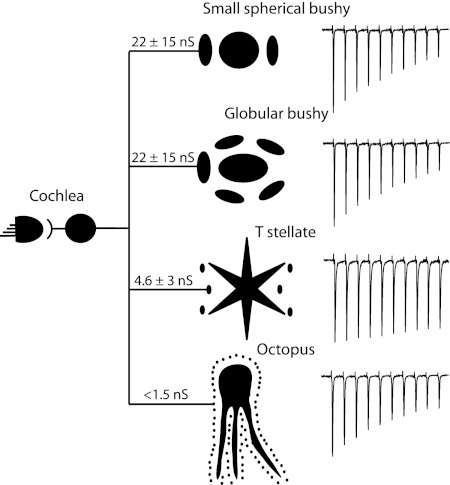

Excitation in the VCN, which arises mainly from myelinated auditory nerve fibers, varies between principal cells in convergence, magnitude, receptors that mediate it, time course, and short-term plasticity. The finding that the functional properties of synapses depend not only on the presynaptic but also on the postsynaptic cell is not unexpected. Synapses are known to be regulated by feedback, necessarily producing synapses whose properties depend on both the presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons (Branco and Staras 2009; Turrigiano et al. 1998). Differences in synaptic properties among several targets of individual neurons have been documented within and outside the cochlear nuclear complex (Branco and Staras 2009; Mancilla and Manis 2009; Reyes et al. 1998). Figure 9 summarizes some of these features diagrammatically.

Fig. 9.

A summary of our conclusions is presented diagrammatically. Individual type I auditory nerve fibers generally receive acoustic information from 1 hair cell and innervate each of the principal cells of the VCN. The average strengths of connections vary between cells and are indicated diagrammatically in the sizes of terminals. The variability of inputs is indicated by the SD of the average conductance. Estimates of the number of auditory nerve fibers that converge on individual principal cells are indicated by the number of endings that surround the cells. Synaptic depression of synapses between auditory nerve fibers and their targets varies as shown in the trains of EPSCs on the right.

Innervation of targets in VCN of mice differs in convergence: T stellate cells receive 6.5 excitatory inputs on average; octopus cells receive too many inputs to count; bushy cells fall into two groups with bushy-s cells generally receiving ≤3 and bushy-g cells receiving ≥4 excitatory inputs. Sharp electrode recordings of responses to shocks of the nerve root from parasagittal slices that contained most of the VCN showed that T stellate cells receive input from five auditory nerve fibers (Ferragamo et al. 1998). Responses to shocks of fiber bundles in patch-clamp recordings from octopus cells in coronal slices also have similar features as sharp electrode measurements to shocks of the nerve root in parasagittal slices (Golding et al. 1995). Both show responses that are almost continuously graded as a function of shock strength. Octopus cells have been estimated to receive input from ≥60 fibers (Golding et al. 1995). Functional estimates of numbers of excitatory inputs to bushy cells have been reported anecdotally. One measurement from a sharp-electrode recording of responses to shocks of the auditory nerve root in parasagittal slices shows four inputs (Oertel 1985); some authors have used the presence of only one or two inputs to identify bushy cells (Isaacson and Walmsley 1995a; Pliss et al. 2009). These measurements of convergence on all cell types likely represent underestimates. The consistency of these measurements in more reduced, coronal slices with shocks to fiber bundles in the vicinity of cells relative to those made in larger and relatively more intact parasagittal slices validates this approach, however.

The magnitude of the AMPA component of excitatory postsynaptic conductances activated by a single auditory nerve fiber varies over a large range. Unitary excitatory inputs are largest in bushy cells, on average 22 ± 15 nS and ranging between 4 and 100 nS; T stellate cells have smaller unitary inputs, on average 4.6 ± 3 nS and ranging between 2 and 11 nS; the smallest excitatory inputs are onto octopus cells, being <1.5 nS. The wide range of unitary conductances is correlated with the wide range in the size of presynaptic terminals; anteriorly where spherical bushy cells are located, many terminals are large end bulbs of Held; anterior and posterior to the nerve root where globular and spherical bushy cells and T stellate cells are found, the size of auditory nerve terminals includes both large and small endings; in the octopus cell, area fibers terminate in uniformly small boutons (Cant and Morest 1979a,b; Cao et al. 2008; Fekete et al. 1984; Gomez-Nieto and Rubio 2009; Lenn and Reese 1966; Liberman 1991, 1993; Lorente de No 1981; Spirou et al. 2005). The wide range in the sizes of auditory nerve terminals raised the question whether desensitization shapes excitatory inputs differently in the three groups of principal cells. AMPA receptors desensitize when neurotransmitter lingers at the synapse. It seemed possible that the removal of neurotransmitter might be faster at the small bouton endings of auditory nerve fibers on octopus cells than at the large end bulb endings on bushy cells and that therefore desensitization affects them less. We found, however, that the application of CTZ to reduce desensitization did not significantly affect the peak amplitude of EPSCs in any of the principal cells and it broadened the EPSCs in all three groups of cells.

Whereas both AMPA and NMDA receptors mediate synaptic responses in each of the groups of principal cells, the NMDA components are relatively largest in T stellate, intermediate in both types of bushy cells, and smallest in octopus cells. In every cell type, the NMDA components are larger in younger than in older mice, as they are in other neurons. The presence of NMDA currents in T stellate cells has been documented (Ferragamo et al. 1998; Isaacson and Walmsley 1995b). In bushy cells, NMDA receptors have been shown to be present and to reach their mature levels at approximately P21 (Isaacson and Walmsley 1995b; Oleskevich and Walmsley 2002; Pliss et al. 2009). In birds also, T stellate–like cells in nucleus angularis have relatively large NMDA components (MacLeod and Carr 2005).

We were surprised to find that AMPA receptors that mediate eEPSCs in T stellate cells are less sensitive to PhTX and show less rectification in the presence of intracellular spermine, indicative of their containing more GluR2 subunits, than the AMPA receptors of bushy or octopus cells (Bowie and Mayer 1995; Kamboj et al. 1995; Washburn and Dingledine 1996). The kinetics of spontaneous EPSCs in T stellate cells are not detectably different from those of bushy or octopus cells (Cao et al. 2008; Gardner et al. 1999). Furthermore, comparison of the function of AMPA receptors in outside-out patches indicates that AMPA receptors in T stellate cells resemble those of bushy and octopus cells in their deactivation, desensitization, and recovery from desensitization kinetics, in their rectification ratios in the presence of intracellular spermine, and in the single channel currents (Gardner et al. 2001). With the exception of T stellate cells, the AMPA receptors of neurons in the VCN, like their avian homologs, have a high Ca2+ permeability (Otis et al. 1995; Raman et al. 1994). The amplitudes of unitary EPSCs in T stellate cells had a unimodal distribution, and there was no more variability in the rectification index of T stellate than bushy or octopus cells, making it unlikely that the mEPSCs in the study by Gardner et al. (1999) arose from assaying a different population of terminals than eEPSCs. It is also unlikely that the observation is an artifact of the inability to clamp the voltage. The I/V relationship was linear in the hyperpolarizing range, and reversal potentials in T stellate cells were similar to those in bushy cells and less positive than those measured in octopus cells or by other investigators under comparable ionic conditions (Isaacson and Walmsley 1995b). In contrast with earlier studies, which involved no synaptic stimulation, recordings in this study required electrical stimulation. Stimulation has been shown to affect the subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors at synapses. In cerebellar stellate cells, activation of synapses causes Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors to be replaced by Ca2+-impermeable ones (Collingridge et al. 2004; Groc et al. 2004; Heine et al. 2008; Liu and Cull-Candy 2000).

Bushy cells have briefer eEPSCs than T stellate or octopus cells. Our results confirm a recent report that the time course of eEPSCs in bushy cells is more rapid than in T stellate cells (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010). Comparisons of durations of eEPSCs with reports in the literature is complicated by their temperature dependence (Kuba et al. 2003). Most measurements of bushy cell eEPSCs have been made over a range of temperatures so they cannot be directly compared with these measurements (Isaacson and Walmsley 1995a,b; Wang and Manis 2005). The time course of EPSCs also depends on the composition of the AMPA receptors and their desensitization, the synchrony of converging inputs, on dendritic filtering, and on the rate of removal of neurotransmitter. Desensitization contributes to the sharpening of EPSCs in all three groups of cells; our results confirm those on bushy and T stellate that were recently reported (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010). Because the AMPA receptors of bushy and octopus cells are similar, differences in the time course of eEPSCs in bushy and octopus cells are likely to result from differences in synchrony in the arrival of inputs. Release of neurotransmitter from numerous small boutons associated with large numbers of fibers in octopus cells may be less synchronous than release from a few large terminals in bushy cells. However, the difference in the time course of eEPSCs in bushy and octopus cells may be smaller than it seems if imperfect control of voltage slows measured eEPSCs in octopus cells. Differences between bushy and T stellate cells could arise also from the presence of slower AMPA receptors in T stellate cells.

Synaptic excitation to T stellate cells suffers less depression than that to bushy and octopus cells. This finding is significant because it indicates that terminals of auditory nerve fibers differ in their presynaptic functional properties as a function of the target; synaptic depression reflects release probability that is determined presynaptically (Oleskevich and Walmsley 2002; Schneggenburger et al. 1999; Silver et al. 1998). Synaptic depression of excitation is common in auditory neurons, reflecting the high release probability of their inputs that is thought to be associated with the ability of many of these neurons to convey precisely timed signals (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001; Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010; Taschenberger and von Gersdorff 2000; Wang and Manis 2008; Zhang and Trussell 1994). The relatively smaller synaptic depression in T stellate cells has been noted previously (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010; Wu and Oertel 1987). The differences in short-term plasticity among targets of auditory nerve fibers have been explored in birds. In neurons of nucleus magnocellularis, excitation of bushy-like neurons shows strong depression and effectively conveys information in the timing of firing (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001; Reyes et al. 1996). In nucleus angularis synapses with balanced facilitation and depression convey information contained in the firing rate (MacLeod et al. 2007).

Two types of bushy cells

Bushy cells have a distinctive morphology but do not comprise a uniform population (Brawer et al. 1974; Lorente de No 1933; Osen 1969). The large spherical, small spherical, and globular bushy cells occupy different parts of the VCN (Brawer and Morest 1975; Cant and Morest 1979b; Osen 1969; Tolbert and Morest 1982b; Willard and Ryugo 1983). Large spherical bushy cells project to the medial superior olive (Harrison and Irving 1966; Smith et al. 1993), globular bushy cells project to the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (Smith et al. 1991; Tolbert et al. 1982), and small spherical bushy cells project to the ipsilateral lateral superior olive (Cant and Casseday 1986). Mice have only few large spherical bushy cells and a small medial superior olive.

Bushy cells vary in their biophysical properties. Bushy cells that fire maximally one or two action potentials at the onset of a depolarizing current pulse have larger low-voltage–activated K+ and hyperpolarization-activated conductances, larger rate-of-depolarization thresholds, lower input resistances, and shorter time constants than bushy cells that fire three or more action potentials. Many features of bushy cells fall into two groups in a cluster analysis, but the distinction between groups is not entirely unambiguous (Cao et al. 2007). In this study, we found that the bushy cells that fired one or two action potentials on depolarization have more inputs than those that fired more action potentials. Several lines of evidence indicate that globular bushy cells receive converging input from more auditory nerve fibers than large spherical bushy cells. Globular bushy cells in cats receive input from between 5 and 62 fibers (Liberman 1993; Tolbert and Morest 1982a), with the most precise estimate being ∼25 (Spirou et al. 2005), whereas large spherical bushy cells are thought to receive input through two end bulbs of Held (Brawer and Morest 1975; Ryugo and Sento 1991). Small spherical bushy cells have not been as well characterized as large spherical and globular bushy cells, and separate estimates have not been made of the number of inputs to small spherical bushy cells. No separate estimates of numbers of inputs have been made in mice.

Sources of excitation to principal cells of the VCN

Myelinated auditory nerve fibers are the major source of excitation for all three groups of principal cells of the VCN and likely mediate most of the excitation evoked by shocks in these experiments, but other excitatory inputs must be considered. A small proportion of auditory nerve fibers have unmyelinated axons whose course through the VCN parallels myelinated fibers (Brown and Ledwith 1990; Morgan et al. 1994). Little is known about how these unmyelinated fibers respond to sound and whether they contact the principal cells of the VCN synaptically. We found no evidence for functional differences between unitary inputs, but the possibility that some excitation arose through unmyelinated auditory nerve fibers or from noncochlear sources cannot be excluded.

Large spherical and globular bushy cells are contacted not only by end bulbs of myelinated auditory nerve fibers but also by noncochlear excitatory terminals (Cant and Morest 1979a; Tolbert and Morest 1982a). In rats and guinea pigs, bushy cells receive input through some terminals that contain VGLUT 1, including those from myelinated auditory nerve fibers, and others that contain VGLUT 2 (Gomez-Nieto and Rubio 2009; Zhou et al. 2007). VGLUT2-containing terminals arise from the spinal trigeminal nucleus and contact dendrites of bushy cells that extend into the granule cell domains (Gomez-Nieto and Rubio 2009; Zhou et al. 2007). The likelihood that these inputs were stimulated in these experiments is low because the stimulating electrodes were not near the granule cell domains where terminals that contain VGLUT2 are located. Bushy cells may also receive excitation through electrical coupling, although we did not observed it electrophysiologically or with biocytin labeling (Cao et al. 2007; Gomez-Nieto and Rubio 2009). We conclude that most of the excitation we measured in bushy cells arises from myelinated auditory nerve fibers.

In addition to receiving input from myelinated auditory nerve fibers, T stellate cells also receive excitation through local circuits within the VCN. Stimulation of the root of the auditory nerve evokes not only monosynaptic but also polysynaptic excitation. T stellate cells likely excite one another because 1) T stellate cells have local axonal collaterals within their own isofrequency laminae in the rostral pVCN where most T stellate cells are located (Oertel et al. 1990) and 2) polysynaptic EPSPs remain even when slices contain only tissue of the VCN (Ferragamo et al. 1998). The number of inputs estimated by steps in responses to shocks of the nerve root (on average, 5.0 ± 0.8; Ferragamo et al. 1998) was smaller than in this study, where it was assessed by shocks to fiber bundles near cells (on average, 6.5 ± 1.0). The difference could have resulted from the inclusion of excitatory inputs from T stellate cells in the present estimate. The amplitudes of EPSCs in T stellate cells have a unimodal distribution, suggesting that if a mixture of inputs from myelinated and unmyelinated auditory nerve fibers and from other T stellate cells were assayed, there was no detectable difference between them. For simplicity, we will interpret all inputs as arising from myelinated auditory nerve fibers.

Octopus cells, whose dendrites spread across auditory nerve fibers where they are tightly bundled, are contacted through small boutons of numerous myelinated auditory nerve fibers (Golding et al. 1995). In mice, but not it cats, the axons of octopus cells have collateral branches within the octopus cell area where there are no other types of neurons (Golding et al. 1995; Rhode et al. 1983; Smith et al. 2005). Shocks to the auditory nerve elicit not only monosynaptic but also disynaptic excitation in mice (Golding et al. 1995). Even if each octopus cell was to contact 10 octopus cells, they would still comprise <15% of the number of inputs.

Processing of acoustic information

In providing most of the excitatory input to four groups of principal cells, small spherical bushy, globular bushy, T stellate, and octopus cells, a single ascending pathway through myelinated auditory nerve fibers is subdivided into multiple parallel pathways, each of which performs a separate integrative task. Together the parallel pathways perform multiple integrative tasks simultaneously, enabling mammals to determine the location of sound sources and the meaning of sounds efficiently and with both temporal and spatial fidelity. The pattern of excitation by auditory nerve fibers is a critical feature of each of the types of principal cells in the VCN in the performance of their different integrative tasks.

The end bulbs of Held provide spherical bushy cells with excitation strong enough to convey the phase of sounds while at the same time sharpening timing by averaging input from multiple fibers. End bulbs produce suprathreshold synaptic potentials that generate action potentials on their rising phase (Kuba and Ohmori 2009; Oertel 1985). At such synapses, the timing of action potentials remains consistent even in the face of synaptic depression (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001). Coincidence of two to four auditory nerve inputs sharpens the encoding of the phase of sounds in large spherical bushy cells of cats with respect to their auditory nerve inputs while still preserving the representation of the fine structure (Brawer and Morest 1975; Cant and Morest 1979a; Joris et al. 1994a,b; Ryugo and Sento 1991; Sento and Ryugo 1989). The small spherical bushy cells presumably also relay the temporal firing pattern of few auditory nerve fibers with “primary-like” responses to sound (Rhode and Greenberg 1992; Young et al. 1993).

More auditory nerve fibers converge onto the globular bushy cells (Liberman 1991; Spirou et al. 2005). The larger convergence produces consistent timing of firing at the onset of tone pips that generates a phasic response; the sharp peak in “primary-like-with-notch” firing patterns encodes onset transients with temporal fidelity (Rhode and Greenberg 1992). The low input resistances, short time constants, and more inputs of globular bushy cells reduce temporal jitter at the expense of preserving the fine structure of sounds. Precision in the timing of firing of globular bushy cells results in precisely timed inhibition in the superior olivary complex that matches the timing of excitation from the contralateral ear and may contribute to coincidence detection in the medial superior olive (Brand et al. 2002; Joris 1996).

Excitation to T stellate cells promotes tonic responses to sound in which sensory information is carried in the rate rather than the timing of firing (Blackburn and Sachs 1989, 1990; Pfeiffer 1966; Rhode et al. 1983). Tonic responses with relatively little adaptation make the population of T stellate cells particularly well suited for conveying spectral peaks and valleys in sounds because the firing rate conveys how much energy is in a receptive field independent of when the sound started. T stellate cells are also particularly well suited to encoding the envelope of complex sounds (Frisina et al. 1990). These results show by what mechanisms T stellate cells convert excitation from auditory nerve fibers that adapt with time to steady firing whose rate adapts little. First, the paucity of synaptic depression reduces adaptation. Second, excitatory current mediated through NMDA receptors amplifies excitation from AMPA receptors not only in magnitude but also in time, blurring information about the fine structure of sounds but lessening adaptation (Ferragamo et al. 1998). Third, feed-forward excitation from other T stellate cells reduces adaptation (Ferragamo et al. 1998). Fourth, the absence of a low-voltage–activated K+ conductance allows T stellate cells to integrate inputs from the auditory nerve (McGinley and Oertel 2006).

Larger numbers of auditory nerve fibers, >60, converge onto octopus cells (Golding et al. 1995). Octopus cells detect coincidence in the excitatory inputs from the auditory nerve (Ferragamo and Oertel 2002; Oertel et al. 2000). Responses to clicks, to the onset of tones, and to periodic stimuli have exceptional temporal precision in octopus cells (Oertel et al. 2000; Rhode and Smith 1986). In cats, octopus cells respond with great temporal precision to low-frequency tones and click trains (Godfrey et al. 1975; Rhode and Smith 1986; Smith et al. 2005).

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DC00176.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Wright for thoughtful comments on reading the manuscript multiple times. P. Chang enabled us to do our statistical analyses, for which we are very grateful. We thank R. Fettiplace and T.Yin for the enjoyable discussions and insightful comments. We also thank the anonymous reviewer who made particularly valuable criticisms and suggestions in a wonderfully positive spirit. This work could not have been performed without the competent help of the staff of the Department of Physiology; we thank R. Kochhar, L. Barnes, S. Krey, D. Buechner, R. Welch, and M. Walker.

REFERENCES

- Bal et al., 2009.Bal R, Baydas G, Naziroglu M. Electrophysiological properties of ventral cochlear nucleus neurons of the dog. Hear Res 256: 93–103, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal and Oertel, 2000.Bal R, Oertel D. Hyperpolarization-activated, mixed-cation current (Ih) in octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 84: 806–817, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal and Oertel, 2001.Bal R, Oertel D. Potassium currents in octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nuclei. J Neurophysiol 86: 2299–2311, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn and Sachs, 1989.Blackburn CC, Sachs MB. Classification of unit types in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus: PST histograms and regularity analysis. J Neurophysiol 62: 1303–1329, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn and Sachs, 1990.Blackburn CC, Sachs MB. The representations of the steady-state vowel sound /e/ in the discharge patterns of cat anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol 63: 1191–1212, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie and Mayer, 1995.Bowie D, Mayer ML. Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion channel block. Neuron 15: 453–462, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco and Staras, 2009.Branco T, Staras K. The probability of neurotransmitter release: variability and feedback control at single synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 373–383, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand et al., 2002.Brand A, Behrend O, Marquardt T, McAlpine D, Grothe B. Precise inhibition is essential for microsecond interaural time difference coding. Nature 417: 543–547, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawer and Morest, 1975.Brawer JR, Morest DK. Relations between auditory nerve endings and cell types in the cat's anteroventral cochlear nucleus seen with the Golgi method and Nomarski optics. J Comp Neurol 160: 491–506, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawer et al., 1974.Brawer JR, Morest DK, Kane EC. The neuronal architecture of the cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol 155: 251–300, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz and Trussell, 2001.Brenowitz S, Trussell LO. Minimizing synaptic depression by control of release probability. J Neurosci 21: 1857–1867, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown and Ledwith, 1990.Brown MC, Ledwith JV. Projections of thin (type-II) and thick (type-I) auditory-nerve fibers into the cochlear nucleus of the mouse. Hear Res 49: 105–118, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant, 1981.Cant NB. The fine structure of two types of stellate cells in the anterior division of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. Neuroscience 6: 2643–2655, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant and Casseday, 1986.Cant NB, Casseday JH. Projections from the anteroventral cochlear nucleus to the lateral and medial superior olivary nuclei. J Comp Neurol 247: 457–476, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant and Morest, 1979a.Cant NB, Morest DK. The bushy cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. A study with the electron microscope. Neuroscience 4: 1925–1945, 1979a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant and Morest, 1979b.Cant NB, Morest DK. Organization of the neurons in the anterior division of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. Light-microscopic observations. Neuroscience 4: 1909–1923, 1979b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao et al., 2008.Cao XJ, McGinley MJ, Oertel D. Connections and synaptic function in the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of deaf jerker mice. J Comp Neurol 510: 297–308, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao et al., 2007.Cao XJ, Shatadal S, Oertel D. Voltage-sensitive conductances of bushy cells of the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 97: 3961–3975, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda and Xu-Friedman, 2010.Chanda S, Xu-Friedman MA. A low-affinity antagonist reveals saturation and desensitization in mature synapses in the auditory brainstem. J Neurophysiol 103: 1915–1926, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge et al., 2004.Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 952–962, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret, 1979.Ehret G. Quantitative analysis of nerve fibre densities in the cochlea of the house mouse (Mus musculus). J Comp Neurol 183: 73–88, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete et al., 1984.Fekete DM, Rouiller EM, Liberman MC, Ryugo DK. The central projections of intracellularly labeled auditory nerve fibers in cats. J Comp Neurol 229: 432–450, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferragamo et al., 1998.Ferragamo MJ, Golding NL, Oertel D. Synaptic inputs to stellate cells in the ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 79: 51–63, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferragamo and Oertel, 2002.Ferragamo MJ, Oertel D. Octopus cells of the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus sense the rate of depolarization. J Neurophysiol 87: 2262–2270, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina et al., 1990.Frisina RD, Smith RL, Chamberlain SC. Encoding of amplitude modulation in the gerbil cochlear nucleus. I. A hierarchy of enhancement. Hear Res 44: 99–122, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino and Oertel, 2001.Fujino K, Oertel D. Cholinergic modulation of stellate cells in the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 21: 7372–7383, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner et al., 1999.Gardner SM, Trussell LO, Oertel D. Time course and permeation of synaptic AMPA receptors in cochlear nuclear neurons correlate with input. J Neurosci 19: 8721–8729, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner et al., 2001.Gardner SM, Trussell LO, Oertel D. Correlation of AMPA receptor subunit composition with synaptic input in the mammalian cochlear nuclei. J Neurosci 21: 7428–7437, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey et al., 1975.Godfrey DA, Kiang NYS, Norris BE. Single unit activity in the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol 162: 247–268, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding et al., 1999.Golding NL, Ferragamo MJ, Oertel D. Role of intrinsic conductances underlying responses to transients in octopus cells of the cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 19: 2897–2905, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding et al., 1995.Golding NL, Robertson D, Oertel D. Recordings from slices indicate that octopus cells of the cochlear nucleus detect coincident firing of auditory nerve fibers with temporal precision. J Neurosci 15: 3138–3153, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Nieto and Rubio, 2009.Gomez-Nieto R, Rubio ME. A bushy cell network in the rat ventral cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 516: 241–263, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groc et al., 2004.Groc L, Heine M, Cognet L, Brickley K, Stephenson FA, Lounis B, Choquet D. Differential activity-dependent regulation of the lateral mobilities of AMPA and NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci 7: 695–696, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison and Irving, 1966.Harrison JM, Irving R. Ascending connections of the anterior ventral cochlear nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 126: 51–63, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine et al., 2008.Heine M, Groc L, Frischknecht R, Beique JC, Lounis B, Rumbaugh G, Huganir RL, Cognet L, Choquet D. Surface mobility of postsynaptic AMPARs tunes synaptic transmission. Science 320: 201–205, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson and Walmsley, 1995a.Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Counting quanta: direct measurements of transmitter release at a central synapse. Neuron 15: 875–884, 1995a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson and Walmsley, 1995b.Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Receptors underlying excitatory synaptic transmission in slices of the rat anteroventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 73: 964–973, 1995b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa and Takahashi, 2001.Ishikawa T, Takahashi T. Mechanims underlying presynaptic facilitatory effect of cyclothiazide at the calyx of Held of juvenile rats. J Physiol 533: 423–431, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris, 1996.Joris PX. Envelope coding in the lateral superior olive. II. Characteristic delays and comparison with responses in the medial superior olive. J Neurophysiol 76: 2137–2156, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris et al., 1994a.Joris PX, Carney LH, Smith PH, Yin TC. Enhancement of neural synchronization in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. I. Responses to tones at the characteristic frequency. J Neurophysiol 71: 1022–1036, 1994a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris et al., 1994b.Joris PX, Smith PH, Yin TC. Enhancement of neural synchronization in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. II. Responses in the tuning curve tail. J Neurophysiol 71: 1037–1051, 1994b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj et al., 1995.Kamboj SK, Swanson GT, Cull-Candy SG. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium-permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. J Physiol 486: 297–303, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba and Ohmori, 2009.Kuba H, Ohmori H. Roles of axonal sodium channels in precise auditory time coding at nucleus magnocellularis of the chick. J Physiol 587: 87–100, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba et al., 2003.Kuba H, Yamada R, Ohmori H. Evaluation of the limiting acuity of coincidence detection in nucleus laminaris of the chicken. J Physiol 552: 611–620, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenn and Reese, 1966.Lenn TR, Reese TS. The fine structure of nerve endings in the nucleus of the trapezoid body and the ventral cochlear nucleus. Am J Anat 118: 375–390, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, 1991.Liberman MC. Central projections of auditory-nerve fibers of differing spontaneous rate. I. Anteroventral cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 313: 240–258, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, 1993.Liberman MC. Central projections of auditory nerve fibers of differing spontaneous rate. II. Posteroventral and dorsal cochlear nuclei. J Comp Neurol 327: 17–36, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu and Cull-Candy, 2000.Liu SQ, Cull-Candy SG. Synaptic activity at calcium-permeable AMPA receptors induces a switch in receptor subtype. Nature 405: 454–458, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente de No, 1933.Lorente de No R. Anatomy of the eigth nerve. III. General plans of structure of the primary cochlear nuclei. Laryngoscope 43: 327–350, 1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente de No, 1981.Lorente de No R. The Primary Acoustic Nuclei. New York: Raven Press, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod and Carr, 2005.MacLeod KM, Carr CE. Synaptic physiology in the cochlear nucleus angularis of the chick. J Neurophysiol 93: 2520–2529, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod et al., 2007.MacLeod KM, Horiuchi TK, Carr CE. A role for short-term synaptic facilitation and depression in the processing of intensity information in the auditory brain stem. J Neurophysiol 97: 2863–2874, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancilla and Manis, 2009.Mancilla JG, Manis PB. Two distinct types of inhibition mediated by cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 102: 1287–1295, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manis and Marx, 1991.Manis PB, Marx SO. Outward currents in isolated ventral cochlear nucleus neurons. J Neurosci 11: 2865–2880, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley and Oertel, 2006.McGinley MJ, Oertel D. Rate thresholds determine the precision of temporal integration in principal cells of the ventral cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 216–217: 52–63, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor and Usherwood, 2004.Mellor IR, Usherwood PN. Targeting ionotropic receptors with polyamine-containing toxins. Toxicon 43: 493–508, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan et al., 1994.Morgan YV, Ryugo DK, Brown MC. Central trajectories of type II (thin) fibers of the auditory nerve in cats. Hear Res 79: 74–82, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak et al., 1984.Nowak L, Bregetovski P, Ascher P, Herbet P, Prochiantz A. Magnesium gates glutamate-activated channels in mouse central neurones. Nature 307: 462–465, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel, 1985.Oertel D. Use of brain slices in the study of the auditory system: spatial and temporal summation of synaptic inputs in cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the mouse. J Acoust Soc Am 78: 328–333, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel et al., 2000.Oertel D, Bal R, Gardner SM, Smith PH, Joris PX. Detection of synchrony in the activity of auditory nerve fibers by octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11773–11779, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel et al., 1990.Oertel D, Wu SH, Garb MW, Dizack C. Morphology and physiology of cells in slice preparations of the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of mice. J Comp Neurol 295: 136–154, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleskevich and Walmsley, 2002.Oleskevich S, Walmsley B. Synaptic transmission in the auditory brainstem of normal and congenitally deaf mice. J Physiol 540: 447–455, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen, 1969.Osen KK. Cytoarchitecture of the cochlear nuclei in the cat. J Comp Neurol 136: 453–484, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis et al., 1995.Otis TS, Raman IM, Trussell LO. AMPA receptors with high Ca2+ permeability mediate synaptic transmission in the avian auditory pathway. J Physiol 482: 309–315, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partin et al., 1993.Partin KM, Patneau DK, Winters CA, Mayer ML, Buonanno A. Selective modulation of desensitization at AMPA versus kainate receptors by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A. Neuron 11: 1069–1082, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, 1966.Pfeiffer RR. Classification of response patterns of spike discharges for units in the cochlear nucleus: tone-burst stimulation. Exp Brain Res 1: 220–235, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliss et al., 2009.Pliss L, Yang H, Xu-Friedman MA. Context-dependent effects of NMDA receptors on precise timing information at the endbulb of held in the cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 102: 2627–2637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman et al., 1994.Raman IM, Zhang S, Trussell LO. Pathway-specific variants of AMPA receptors and their contribution to neuronal signaling. J Neurosci 14: 4998–5010, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes et al., 1998.Reyes A, Lujan R, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Somogyi P, Sakmann B. Target-cell-specific facilitation and depression in neocortical circuits. Nat Neurosci 1: 279–285, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes et al., 1996.Reyes AD, Rubel EW, Spain WJ. In vitro analysis of optimal stimuli for phase-locking and time-delayed modulation of firing in avian nucleus laminaris neurons. J Neurosci 16: 993–1007, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]