Abstract

Light-absorbing endogenous cellular proteins, in particular cytochrome c, are used as intrinsic biomarkers for studies of cell biology and environment impacts. To sense cytochrome c against real biological backgrounds, we combined photothermal (PT) thermal-lens single channel schematic in a back-synchronized measurement mode and a multiplex thermal-lens schematic in a transient high resolution (ca. 350 nm) imaging mode. These multifunctional PT techniques using continuous-wave (cw) Ar+ laser and a nanosecond pulsed optical parametric oscillator in the visible range demonstrated the capability for label-free spectral identification and quantification of trace amounts of cytochrome c in a single mitochondrion alone or within a single live cell. PT imaging data were verified in parallel by molecular targeting and fluorescent imaging of cellular cytochrome c. The detection limit of cytochrome c in a cw mode was 5 × 10−9 mol/L (80 attomols in the signal-generation zone); that is ca. 103 lower than conventional absorption spectroscopy. Pulsed fast PT microscopy provided the detection limit for cytochrome c at the level of 13 zmol (13 × 10−21 mol) in the ultra-small irradiated volumes limited by optical diffraction effects. For the first time, we demonstrate a combination of high resolution PT imaging with PT spectral identification and ultrasensitive quantitative PT characterization of cytochrome c within individual mitochondria in single live cells. A potential of far-field PT microscopy to sub-zeptomol detection thresholds, resolution beyond diffraction limit, PT Raman spectroscopy, and 3D imaging are further highlighted.

Keywords: photothermal spectroscopy, photothermal microscopy, imaging, trace analysis, molecular targeting, cytochrome c, mitochondria, live cells

1. Introduction

Mitochondria play a central role in the cell metabolism and cell response to environmental and therapeutic intervention [1, 2]. This role includes cellular energy processes, free radical generation, apoptosis, the participation the mitochondrial proteins (e.g. cytochrome c [cyt c], cyt c oxidase, and others) in photobiological reactions or as a potential target in low-dose phototherapy, and correlation of some mitochondria functions with the development of cancer [3–8] and age-dependent degenerative, in particular neurodegenerative, diseases [9]. Many functional parameters of mitochondria are directly based on, related to, or attributed to cellular chromophores, in particular cyt c [10–12]. Thus, it is crucially important to know the state, amount, and location of cyt c in mitochondria-related samples.

Nowadays, many accepted methods for the identification and quantification of cyt c are based (either directly or indirectly) on accompanied functions. For example, the studies on cyt c in isolated mitochondria typically use ELISA or Western blotting as biochemical detection methods, which impose a number of experimental limitations [13, 14]. In particular, Western blotting is a semiquantitative method that cannot give precise information about the amounts and kinetics of cyt c release under specific conditions. Both these methods have also lengthy procedures, so that the results cannot be obtained on a time-scale of the actual experiments as desirable. Chemical approaches like reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography to quantify cyt c were also introduced [15]. In general, the existing biochemical analyses are not only invasive but often not specific and hence inefficient. Moreover, most of these methods do not have imaging function, which is important to increase the analytical potentialities by additional morphological and structural analysis.

Thus, complex investigations of mitochondria as key biological entities requires spectroscopy, namely all of its three ‘dimensions’: spectrometry (qualitative spectral information), radiometry (quantitative intensity information), and imaging (mapping, spatial information).

Various optical imaging techniques have been successfully used to characterize cellular proteins, in particular cyt c [16–33]. Nevertheless, there exist a number of limitations for the identification and imaging of proteins at a sub-cellular level, especially for weakly fluorescent, low-scattering and low-refractive proteins. This demands a novel technology for sub-cellular protein spectral mapping.

To the contrary, absorption spectroscopy (spectrophotometry), which uses specific absorption signatures (so-called fingerprints) of biomolecules, has the potential for label-free identification of most proteins, including catalase, peroxidase, flavoproteins (e.g. NADH dehydrogenase), cytochromes (P450, b5, a, c, c1, b), cyt c oxidase, and many others [16, 17]. Most of these proteins exhibit relatively narrow spectral bands in the visible and near-infrared range of 400–900 nm, with no significant interference from DNA, RNA, lipids, and water, which absorb mainly in the ultraviolet (< 350 nm) and infrared (> 950 nm) ranges. Specifically, spectrophotometric methods were used for study of cyt c release from isolated mitochondria or permeabilized cells [21–23]. For this, the Soret peaks at 414 nm or 530 and 550 nm (for the reduced form of cyt c) were measured. However, low sensitivity of absorption spectroscopy requires a high concentration of cells in suspension to be characterized (the data on the use of a cell monolayer are scant [24]). Furthermore, most techniques of absorption spectroscopy measure only the average transmittance within whole, strongly absorbing, cells with relatively low spatial resolution, and that prevents the mapping and spectral identification of cellular structures [18–20].

As an alternative to conventional absorption spectroscopy, photothermal (PT) and photoacoustic (PA) techniques using the transfer of absorbed energy into heat and accompanied phenomena can fix this gap. In these techniques, laser-induced thermophysical effects are detected by thermometry, infrared radiometry, dual-beam (pump–probe) thermal lensing, beam deflection (e.g., “mirage” effects), phase-contrast, polarization-interference contrast, heterodyne, or acoustic schematics (see reviews [20, 34–40] and references cited therein). Being true methods of molecular absorption (not transmittance) spectroscopy, they combine the abovementioned features of spectrophotometry and the power-based spectroscopy benefitting from intense light sources and exhibiting near-single-molecule detection [20, 40].

Historically, first PT and PA microscopies (PTM and PAM, respectively) in a laser-scanning mode were developed in 1960–1970s (see the review chapter in [41]). In particular, one of the first scanning PAM using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser at a wavelength 1.06 μm and a transmission acoustic microscope demonstrated a resolution of 2 μm for nonbiological objects [42]. PTM based on a time-resolved dual-beam phase-contrast non-scanning (for one cell) schematic with nanosecond excitation in various modifications demonstrated the capability to label-free imaging of individual pigmented (e.g., erythrocytes) and non-pigmented cells in vitro (e.g., [43–51], see also the review [20] and reference therein). The scanning PT thermal-lens microscope with cw intensity-modulated excitation laser at 532 nm was used for imaging of cellular cyt c distribution during apoptosis with a resolution of ca. 1 μm [52]. Further development of PTM included PT thermal-lens multiplex microscopy [53], the principle of far-field PTM beyond the diffraction limit [54], the nanocluster theory of PTM [55], PT image flow cytometry in vitro and in vivo [56–61], imaging of mitochondria in a live cells with high-sensitivity heterodyne schematics [62], in vivo PT Raman microscopy of nonabsorbing sub-cellular structures in near-infrared range [63], and the detection and imaging of nanoparticles in various environments [20, 34–36] (this topic is out of this paper scope). The first applications of these techniques operating mostly at 532 nm were a study of apoptosis [52, 53, 55, 64–67,] and respiratory chain [68] with an assumption that cyt c is one of the main PT intracellular targets.

However, the PT data have not been quite correlated directly with cyt c contents or verified with conventional assays over a large concentration range up to day. Furthermore, simultaneous PT imaging and PT spectroscopy of cellular structures, particular individual mitochondria in the spectral range of cyt c absorption (530–560 nm), have not been accomplished yet, although both tasks are very important for identification and mapping of potential PT intrinsic cellular markers. The aim of this paper is to fill in this gap in PT study of cyt c by estimating performance of label-free high sensitive PT-based techniques in spectral identification, quantitative characterization, and imaging of cyt c in live cells and its release from mitochondria with advanced PT techniques based on the thermal-lens effect.

2. Experimental

The dual-beam PT techniques with cw and pulses lasers were used in this work and the features of its functioning were described previously in detail [20, 69–72]. Below, we briefly summarize these parameters.

2.1. Photothermal thermal-lens spectrometer with a cw excitation beam

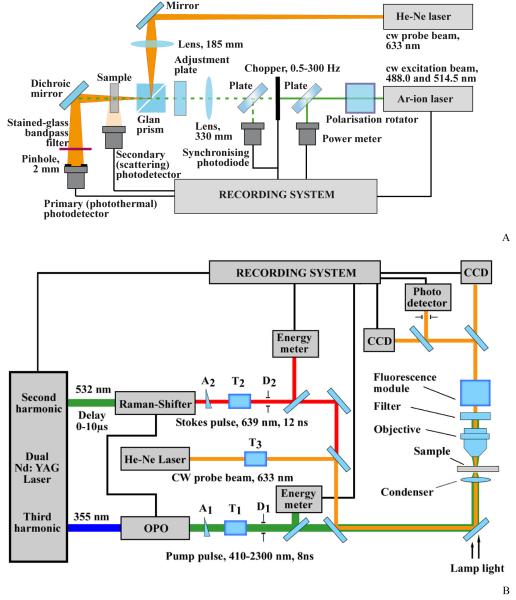

The single-channel thermal-lens spectrometer (Figure 1A) uses a discretely tunable cw Ar+ excitation (also referred to as pump) laser (Innova 90-6, Coherent, Palo Alto, CA 94303, USA) with wavelengths (power range in the sample, mW): 514.5 nm (40–1500), 501.7 nm (5–60), 496.5 nm (4–90), 488.0 nm (5–1000), 476.5 nm (5– 82), 472.7 nm (2–20), and 465.8 nm (2–12); TEM00 beam waist diameter, 59.8 ± 0.5 μm. Absorption of the excitation radiation by the sample induces refractive heterogeneity (thermal-lens effect) causing defocusing of a TEM00 collinear He–Ne laser probe beam (SP-106-1, Spectra Physics, Eugene, OR 97402, USA; wavelength, 632.8 nm; waist diameter, 25.0 ± 0.2 μm; power, 4 mW). Local increase in temperature due to the PT effect is 0.001–20°C, thus from completely noninvasive to invasive impacts.

Figure 1.

Schematics of PT techniques used (A) dual-beam PT thermal-lens spectrometer; and (B) transient PT microscope–spectrometer (see text for details).

A reduction in the probe beam intensity at its centre is detected by a far-field photodiode (sample-to-detector distance, 180.5 ± 0.1 cm) supplied with a KS-11 stained-glass bandpass filter and a 2-mm-diameter pinhole (Figure 1A). The measurement synchronization is implemented by in-house written software [69]. The PT spectrometer had a linear dynamic range of the signal of four orders of magnitude (the corresponding range of absorption coefficients for 10 mm optical pathways is 1 × 10−6 to 2 × 10−2 cm−1) and response time of 0.05–2 s (depending on the selected measurement parameters, namely, on the data throughput rate and time, the number of points to be averaged, etc) [70, 72]. The spectrometer implements a secondary optical channel (Figure 1A), for gathering scattering or luminescence signals, if present.

The thermal-lens spectrometer implements back-synchronized measurement mode [69]. This measurement mode features different measurement conditions for the blooming and dissipating of the thermal lens. In this excitation/data-treatment mode, the advantages are (i) the possibility of detection under batch and flow conditions with no change in the optical-scheme design of the instrument; (ii) the possibility to switch between transient and steady-state measurements within a single set of experiments; and (iii) a wide linear dynamic range (more than five orders of magnitude of detectable absorbances) including strongly absorbing and scattering samples [70]. In spite of a somewhat lower detection sensitivity compared to more commonly used lock-in detection schemes in thermal-lens spectrometry, the flexibility of this measurement mode provide a much larger volume of information, making it a powerful tool for solving so not-straightforward problems like studies of complex formation at trace concentrations, transient heat dynamics around absorbing nanoparticles, etc. [70, 72, 73].

2.2. Transient-mode photothermal microscope-spectrometer with a pulsed excitation beam

The PT microscope (PTM) with spectrometer function (Figure 1B) was built on the technical platform of an upright Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA) with incorporated PT, fluorescent, and transmission microscope modules [20, 53]. A tunable optic parametric oscillator (OPO) (LT-2214, Lotis Ltd., Minsk, Belarus) was used to irradiate samples in microscopic slides with thick (120 μm) or thin ( ~1 μm) layer of cells or mitochondria suspension at the following parameters: wavelength, 420–2,300 nm; pulse width, 8 ns; maximum pulse energy, 5 mJ; fluence range, 1–104 mJ/cm2; line width, ~0.5 nm; polarization signal and idle wave, horizontal; and the pulse repetition rate, 10 Hz.

In PT single-channel thermal-lens mode, a laser-induced temperature dependent variations of the refractive index around absorbing targets caused the defocusing (thermal-lens effect) of a collinear probe beam from a cw stabilized He–Ne laser (wavelength, 632.8, nm; power, 1.4 mW; model 117A, Spectra Physics Inc., USA). The subsequent reduction in the beam’s intensity at its center was detected after a pinhole by a photodiode with a C5658 preamplifier (Hamamatsu Corp.) as the PT signal from the irradiated volume. In the linear mode, PT signals demonstrated a high initial positive peak due to fast (nanosecond scale) heating of the absorbing structure and a much longer (microsecond scale) exponential tail corresponding to the cooling of a cell (or a mitochondrion) as a whole. For a typical laser fluence of 10–104 mJ/cm2 in the visible and near-infrared range for cells with different absorbing profiles, local temperature ranged from 0.01–1°C to 100–300°C, thus providing a very broad spectrum action from completely noninvasive to invasive impacts, respectively, with appearance of nonlinear nano- and microbubble formation phenomena.

In PT imaging (PTI) mode, the refractive index variations were visualized with multiplex (multi-channel) thermal-lens schematic and a CCD camera (Apogee), using the excitation (OPO) laser pulse and second, probe pulse (Raman Shifter; wavelength, 639 nm; pulse width, 12 ns; pulse energy, 2 nJ; 0–10 μs delay).

Refractive index variations were obtained by comparison of the sample images before and right after the excitation laser pulse (i.e., as in previous schematics [20, 43, 48]), but with each pixel of CCD camera acting as an individual photodetector with a pinhole as in a single-channel thermal-lens mode [53]. Thus, wide-field CCD-based PT microscopy is equivalent to a multi-channel thermal-lens imaging system with one of the highest diffraction-limited resolution. The lateral resolution was of 700 nm with a 20× microobjective and ~350 nm with a 60× water-immersion objective. The excitation and probe beam diameters are adjustable (range 10–60 μm and 5–50 μm, respectively) by changing condensers and moving them along beam axes. Thermal diffusion during a laser pulse (detection time) extends PT images on a few tenths of nanometers [55] that is much less than diffraction limits. The target area in slide was navigated by using an automatic scanning microscopic stage (Conix Research, Inc) and in-house written Visual Basic™ software.

2.3. Data treatment

A single measurement of the transient PT signal ϑ(t) for a shutter on-off cycle of the cw or a pulse of the pulsed excitation beam was calculated as the phase shift in the probe beam wavefront Φ at a distance z from a laser source and a distance from the beam centre r at time t

| (1) |

(λp is the probe laser wavelength, l is sample pathlength, dn/dT is the temperature coefficient of the refractive index (the thermooptical constant), and ΔT is a photothermal temperature change) as a relative change in the probe-beam intensity ϑ(t) =[Ip(0) – Ip(t)]/Ip(t) as [74].

| (2) |

where Ip(0) is the intensity of the probe beam at the photodetector plane in the central part of the beam at the time t = 0 (from this point on, the subscript “p” will denote the probe beam, and the subscript “e” will stand for the excitation beam), and Ip(t) is the intensity of the probe beam at the moment t, Pe is the excitation laser power, ω0e is the excitation beam waist radius, B(t) is the time-dependent geometrical constant of the optical scheme, DT is thermal-diffusion coefficient, α is the linear absorption coefficient of the sample, ε is the molar absorptivity, с is molar concentration of the absorbing substance in the sample. The factor E0 is the enhancement factor of thermal-lens effect for unit excitation laser power

| (3) |

where k the thermal conductivity. The tc is the characteristic time of the thermal lens [74]:

| (4) |

For steady-state measurements in a cw mode, (2) converts to

| (5) |

Where θ is steady-state PT signal corrected for the geometry constant B(t → ∞). The experimental values of the PT signal θ were corrected to take into account a decrease in the excitation power due to light-scattering losses As in solutions:

| (6) |

where A is sample absorbance. The recalculation of the absorbance from photothermal measurements (APT) were calculated from the equation deduced from (2) and the Lambert–Beer law A = εlc

| (7) |

Whenever possible, the experimental values of sample absorbance Aexp were corrected to scattering

| (8) |

For cells and mitochondria, the previously developed theoretical description for signal generation in PT spectroscopy for multipoint-absorbing (disperse) solutions is used [75]. This approach is based on the same calculation of the signal (2) from the phase shift (1), but the temperature change ΔT(r, z, t) is found by a summation of individual thermal waves from multiple heat sources distributed in N thin layers plus the conventional contribution from the light-absorbing background with a due account for the random movement (shift) of the heat sources in the signal-generation process).

| (9) |

Here, M is the number of excitation pulses in a train (cw excitation is simulated with a large number of ultrashort pulses). The second double-sum term represents the shifting of the heat element during the heating period by substituting the initial variables (r, z) to (r + R, z + Z), where (R, Z) is the shift vector. Thus, summing the shifted heat functions, Eq. (9), gives a picture of heat-generation in the system without binding it to the radial symmetry of the excitation beam. The model represents heat flow from every individual heat source; thus, resulting in the exact spatially resolved thermal picture, which is much closer to the real situation in the description of dilute solutions. The PT characteristics for heterogeneity are not considered in the calculation of the heat diffusion as the contribution of the total heat-source volume to the total sample volume is negligible, and the heating of heterogeneity is considered instantaneous, thus, only the PT properties of the medium are taken into account.

The applications of a quasi-cw function for the description of the solution excitation do not prevent the calculation of transient functions of the temperature profile and PT signal.

The temperature distribution in the layer i, ΔTi is based on a separate consideration of the axial (below, the term in curly brackets) and radial (the term in square brackets) components of the temperature profile:

| (10) |

Here Ii-1 is the intensity of the excitation radiation incident to the layer i. The parameter t0 is the quasi-pulse duration (expresses the energy transmitted to the absorbing medium only, while the transfer of the total pulse energy is considered instantaneous [75]). This equation is used as is for pulsed excitation. The temperature response on cw irradiation is achieved by the summation of the temperature responses on a series of laser quasi-pulses, with each quasi-pulse starting at the moment tn = (n – 1)t0, where n is the ordinal of the quasi-pulse. Heat-dissipation functions from different heat sources form the final temperature profile. The heat-wave profiles generated by different heat sources are described with the same function and PT response amplitudes differ according to the particle position in the excitation laser beam.

2.4. Other measurements

Measurements of absorbance and absorbance spectra with a 0.5-nm resolution were made using an UV-mini-1240 (Shimadzu, Japan) and Cary 5000 (Varian) spectrophotometers. The estimations of scattering effects were performed with the cw PT spectrometer (section 2.1) with a modulated excitation beam at 514.5 nm in absence of a probe beam. The scattered light was detected by the photodiode (the stained-glass bandpass filter and the pinhole removed) in a continuous intensity detection mode.

2.5. Reagents and procedures

Cyt c from equine heart, 99% (Sigma, USA, M = 12383) for biochemistry; sodium dodecyl sulfate (99%, Fluka, М = 288.4); analytical grade NaH2PO4·2H2O, NaOH, and KCl (Sigma-Aldrich, USA); and cp ascorbic acid (Sigma, USA) were used throughout. KB-3 human cancer cells (HeLa cells) were purchased from ATCC, Rockville, MD and cultured according to standard manufacturer procedures. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 5 mM L-glutamine at 37°C and 5% CO2.

For the imaging of mitochondria, cells were treated with 0.1 μM MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Molecular Probes, OR) for 30 min before fixation. Cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X100. For cyt c staining, cells were treated with anti-cyt c antibody according to manufacturer’s instructions (Pharmingen, CA, USA). Anti-cyt c treated cells were visualized with Oregon Green-conjugated second antibody (Molecular Probes, OR). The cells were studied both on substrate and in suspension in sealed chambers (S-24737; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a concentration of 104 cells/ml and total volume ~6.7 μl.

For analysis of the release of cyt c rat liver mitochondria were isolated by standard differential centrifugation techniques [76, 77] in a buffer containing mannitol (210 mM), sucrose (75 mM), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (Hepes, CAS no. 7365-45-9, 10 mM), ethylenebis-(oxyethylenenitrilo)-tetraacetic acid, (EGTA), 1 mM, and 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) pH 7.4. BSA and EGTA were present in the isolation medium but were absent from the medium used for suspending of mitochondria. All steps were performed at 4°C, and mitochondria were stored on ice. After the isolation, a part of mitochondria were re-suspended and incubated in media containing 0.21 M mannitol, 0.075 M sucrose, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 (sample types #1–#3). Alternative incubation media contained 0.15 M KCl, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 (sample types #4–#6). Mitochondrial protein concentrations were the same in all the samples (4.0 mg/ml). Mitochondria were energized with the 5 mM succinate in the presence of 1 μM rotenone. To induce the cyt c release from mitochondria, the induction of mitochondrial permeability transition was performed by the addition of 1 mM KH2PO4 and, after 5 min, of 50 mM CaCl2 (sample types #2 and #5), or 50 mM CaCl2 and, after 5 min, of 1 mM KH2PO4 (sample types #3 and #6). The same volumes of these substances was added to control samples (types #1 and #4). Incubations lasting for 30 min were carried out at 30°C in cuvettes that were open to the atmosphere, with stirring, to maintain an availability of O2. Next, all the samples were centrifuged (3000g, 10 min., 4°C) and supernatants were analyzed for the estimating of the released cyt c.

2.6. Statistical treatment

Results are expressed as means plus/minus the standard deviation and confidence interval of at least three independent experiments (P = 0.95). Statistica 5.11 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK) and MATLAB 7.0.1 (MathWorks, Natick, MA) were used for the statistical calculations. Data were summarized as the mean, standard deviation (SD), relative standard deviation, median, interquartile range, and full range. The error bars in figures represent SD in 5 measurements. Limits of detection and quantification were calculated by 3S/N and 10S/N criteria, respectively. The measurement precision was analyzed using simple variance analysis as repeatability (deviation between the same concentration) and reproducibility (day-by-day deviation).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Imaging and identification of mitochondria and cytochrome c in single live cells with transient pulsed PT thermal-lens technique

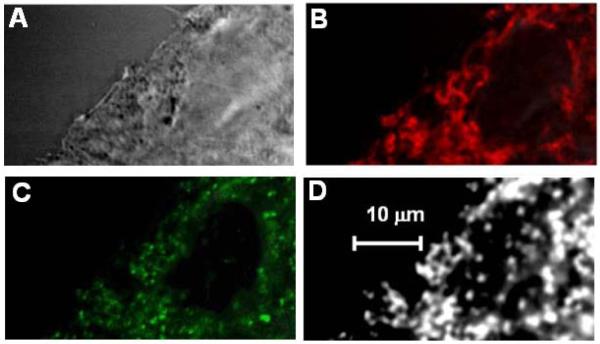

To verify the nature of PT cellular chromophores in visible range for KB-3 cells (also termed as HeLa) we applied transient PTM to image distribution of these chromophores in the cell. PTM imaging was integrated with phase-contrast and fluorescent techniques. According to previous findings [53], the quality of a PT image was superior when cells were visualized on a substrate rather than in suspension, and subcellular structures and their boundaries were more clearly observed. The PT image contrast (Figure 2D) was better than phase-contrast image of the same cells with imaging resolution of the same level (Figure 2A); the nature of both images is completely different (absorption and refraction heterogeneities, respectively). When cells were labeled with MitoTracker Red (Figure 2B), the resulting fluorescent image had a pattern very similar to that of the PT image (Figure 2D), suggesting that the main PT (i.e. absorbing) targets are located in the mitochondria. These targets could be associated with absorption mainly by cyt c, which was confirmed by the similarities between the PT image (Figure 2D) and the corresponding fluorescence images of molecularly targeted cyt c in the same cells (Figure 2C). Based on our previous experience in this field [53], to obtain simultaneously PT and fluorescent images from the same cell, the wavelength of excitation laser in PT measurement was selected as 538 nm, which was close to the absorption maximum of cyt c and was far enough from the absorption maximum of both Oregon Green (488 nm) and MitoTracker Red (580 nm) used for labeling of cyt c and mitochondria, respectively. It should be also noted that the PT images were obtained with a single excitation laser pulse with a total acquisition algorithm taking 0.2 s and were stable after many laser pulses (at least 10–20) under noninvasive conditions at energy fluence in the range of 0.1–0.5 J/cm2, which is much lower than a photodamage thresholds for nonpigmented cells in this spectral range [20, 51]. Additional measurements of the PT spectra of individual local zones in PT images in non-labeled cells at different wavelengths of the excitation laser revealed a reasonable correlation with the conventional spectrum of cyt c, at least in the spectral range of 530–560 nm (similar to presented below).

Figure 2.

KB-3 cells chromophores: (A) Phase-contrast image of a KB-3 cell fragment on substrate (Axioskop 2, Zeiss, 60×, NA, 1.3); (B) fluorescent imaging of cellular mitochondria labeled with MitoTracker Red; (C) fluorescent imaging of cyt c labeled with Oregon Green conjugated with anti–cytochrome-c antibody; (D) label-free PT images of the same cell (60× objective); excitation wavelength 538 nm, laser fluence 100 mJ/cm2, and 5 ns delay between excitation and probe pulses.

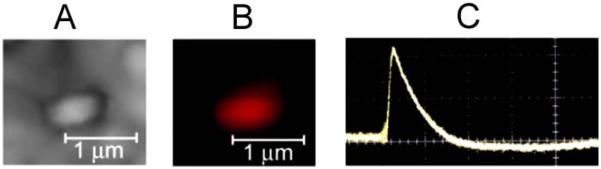

To verify PT data at a mitochondrial level, we obtained PT and fluorescent images (Figure 3A and 3B) as well as the PT thermal-lens responses from individual mitochondria isolated from KB-3 cells. Figure 3C demonstrates that the signal to noise ratio approximately at level 10 can be achieved with one laser pulse at energy fluence of 0.5 J/cm2 suggesting high sensitivity of PTM at single mitochondrion level.

Figure 3.

High-resolution PT (A) and fluorescent (MitoTracker Red labeling) images (B) and PT response (C) from a single mitochondrion in solution (time scale is 1 ms/div). Laser wavelength 538 nm; fluence 0.5 J/cm2.

This finding is consistent with previous ours [53] and other researches [21–23, 52] data demonstrating that in the spectral range used, the dominant cellular local absorption is likely determined by mitochondrial cyt c. However, our new PT images revealed also some additional structures compared to fluorescent images that might indicate potential contribution in PT response of other cellular proteins as we and other previously discussed [53, 55, 62]. Although we cannot exclude also that a high sensitivity, PTM revealed a small amount of cyt c in cytosol, which is invisible with other techniques or partly released from mitochondria during preparation procedures. Nevertheless, this issue requires further detailed study with focus on accurate identification of cellular light absorbing proteins in broad spectral range using a high resolution multispectral PT imaging technique.

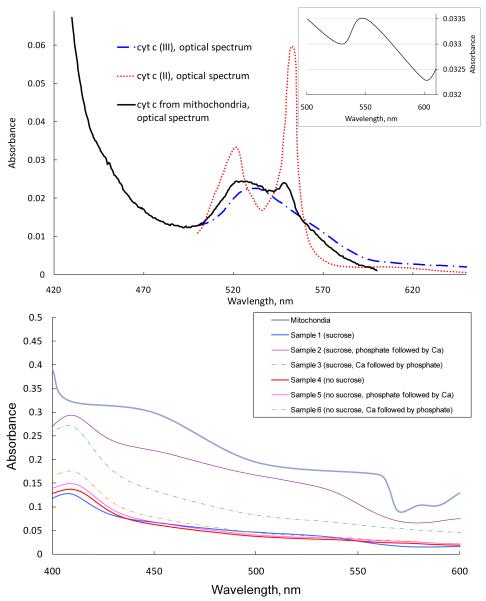

3.2. General comparison of PT vs. conventional absorbance measurements

Next, we estimated the capability to identify absorption and PT spectroscopy to identify of cyt c in various environments. For general comparison, we measured absorption spectra of free forms of cyt c, cells (hepatocytes) and mitochondria in suspension using one of the best conventional spectrophotometers, a Varian Cary 5000. The spectra of free forms of cyt c showed good concordance with the existing data (Figure 4A). Indeed, cyt c is a major cellular component located mainly in mitochondria [23] with a clear absorbing band in the spectral range of 520–560 nm with a maximum near 530 nm for oxidized form; 520 nm and 550 nm for reduced cyt c. However, these data are distorted by scattering, and even in the samples with cyt c released from mitochondria (sample types #1–#6) show low absorbance values, although it is evident that samples #2 and #3 (induction of mitochondrial permeability transition in mitochondria incubated with sucrose) show higher absorbances with an increase in the Soret peak (Figure 4B). If the scattering correction is performed, one can see that cyt c released from mitochondria is mainly cyt c (III) with a 10% of cyt c (II) (Figure 4A); however, the overall spectrum quality is degraded.

Figure 4.

Conventional absorption spectra of (A) pure forms for cyt c (II) and cyt c (III) and cyt c released from mitochondria (a sample #1, corrected for scattering) (2 μM), (B) isolated mitochondria suspension and sample of cyt c released from mitochondria under various conditions (see the text for sample types #1–#6 description; and (inset) rat hepatocyte cells in suspension in concentration 5 × 106 cell/mL (Spectrophotometer Cary 5000, Varian, Inc).

When shifting from organelles to whole cells, the same trend is more evident: despite a high concentration of cells (5 × 106 cells/mL) and a 1-cm optical path length, conventional spectra showed just very weak absorption peaks (associated with cyt c in mitochondria) because of the low absorption by the cells and the influence of optical scattering effects, even with differential schematics (Figure 4A, the inset). The same approach with scattering correction, Eq. (8) is not possible due to the fact that As >> A.

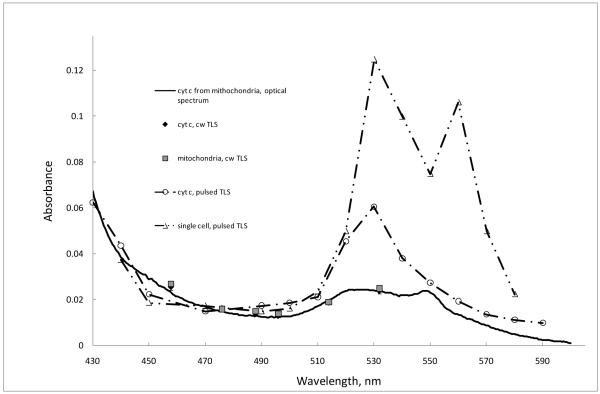

In contrast, PT cw and pulsed techniques, which are not significantly affected by light scattering, provided clear spectra from hydrolyzates, mitochondria, and single cells showing strong absorption peaks coinciding with the cyt c peaks in solution (Figure 5) for 100-fold lower cyt c concentrations. In all the cases, scattering effects were insignificant, although the spectrum correction according to Eq. (6) was proved useful to increase the signal-to-noise ratio especially for weakly absorbing solutions. These findings fit well with the comparison of general sensitivities of conventional absorbance measurements and PT measurements in neat solutions [71]. Thus, shifting to more complicated biological systems does not change the general sensitivity of PT thermal-lens measurements compared to neat solutions.

Figure 5.

Absorption spectra APT(λ) obtained from cw and pulsed PT measurements (Eq. (7)) of cyt c solution (2 μM), mitochondria and single cells. The same conventional absorbance spectrum as in Figure 4A is given for comparison reasons.

3.3. Identification and quantification of trace cytochrome c by PT techniques

Next, we compared quantitative PT data obtained with cw and pulsed schematics. The concentrational calibration plots for all the excitation lines of the lasers used allowed us to calculate PT absorption spectra of cyt c (by recalculating absorbance from PT signals using Eq. (7). It shows that the cw PT measurements do not impose any changes on the absorption-band properties of cyt c: the comparison of absorbance spectra of cyt c with its PT spectra shows no difference the values of the molar absorptivities (Figure 5, compare the conventional spectrum and PT spectrum, solid line, and PT measurements, black rhombs). Moreover, the data from free cyt c and mitochondria solutions (sample types #1, #2, #4, and #5), also show no difference as expected, and the precision of measurements of free cyt c and cyt c released from mitochondria also differ negligibly. As a whole, the precision of the measurement is high enough for the PT quantification of cyt c.

The selection of the excitation wavelength 514.5 nm in the cw mode was dictated by the maximum power of this excitation line thus giving sufficient PT sensitivity (calculated as Peα): approximately a 40-fold enhancement compared to absorption spectroscopy.

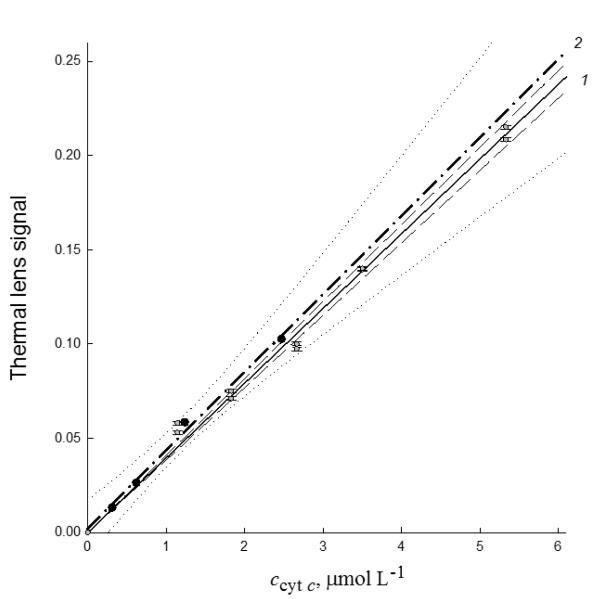

The sensitivity of the determination of cyt c (III) is determined (Figure 6, curve 1). The comparison of variance parameters shows very good repeatability (relative standard deviation, 0.01) and reproducibility (relative standard deviation, 0.02). The calibration plot for cyt c in neat solutions is described with the equation (excitation power 140 mW, 514.5 nm); the intercept of this curve is statistically negligible:

where c is the micromolar concentration of cyt c. The limit of detection of cyt c under these conditions is 4 × 10−9 mol/L (0.05 mg/L of cyt c released from mitochondria; 2.7 ± 0.1 μg/mL of the total protein from mitochondria calculated according to [77, 78]), the limit of quantification is 2 × 10−9 mol/L. The detection limit value is one order lower than previously reported for cyt c with the same schematic [71] due to more advanced conditions of sample preparation and higher focusing of the laser beam giving better fluence.

Figure 6.

The calibration plots of PT signal (514.5 nm, excitation power 12 mW) on the concentration of (1) cyt c in neat solutions, solid line, dashed confidence interval and (2) cyt c released from mitochondria (solutions of sample type #1), dash-dotted line, dotted confidence interval. The data for the calibration plots were collected in three days, the repeatability relative standard deviation 0.02.

Under the same conditions, the calibration plot for cyt c released from mitochondria (Figure 6, curve 2) corrected to the scattering by Eq. (6) is

| (11) |

Thus, the calibration plot has just slightly higher slope compared to neat solutions, and a relatively small intercept (only twice higher than the background value, see Table 1 below). In other words, the effects of solution composition on the signal are minor and can be seen only for relatively high concentrations (Figure 7) without affecting the action spectra (Figure 5).The limit of detection of cyt c under these conditions is 5 × 10−9 mol/L (0.07 mg/L of cyt c released from mitochondria; 3.1 ± 0.1 μg/mL of the total protein from mitochondria). The limit of detection is 100-fold lower than the value obtained with conventional absorbance measurements, which is in concordance with the data discussed in Section 3.2. The minimum detectable absorbance from PT measurements is (1.70 ± 0.05)× 10−5, which is in good agreement with the calculations of the theoretical value of 1.3 × 10−5 absorbance units from [71].

Table. 1.

Results of determination of cyt c released from mitochondria by cw thermal-lens spectrometry, λe = 514.5 nm, excitation power 12 mW (n = 15, P = 0.95)

| Sample type | PT signal | PT signal increase compared to the reference sample |

Calculated cyt c conc., μmol/L (Eq. (11) |

Average cyt c conc., mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 0.0135 ± 0.0006 | — | — | — |

| Mitochondria (dilution 1 : 100) | 0.13 ± 0.04 | — | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 42 |

| Type #1 (reference) | 0.099 ± 0.002 | — | 2.47 ± 0.03 | 30 |

| Type #2 | 0.108 ± 0.008 | 0.009 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 33 |

| Type #3 | 0.112 ± 0.008 | 0.013 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 35 |

| Type #4 (reference) | 0.100 ± 0.002 | — | 2.48 ± 0.03 | 30 |

| Type #5 | 0.101 ± 0.005 | 0.001 | 2.53 ± 0.07 | 31 |

| Type #6 | 0.103 ± 0.005 | 0.004 | 2.61 ± 0.06 | 32 |

Figure 7.

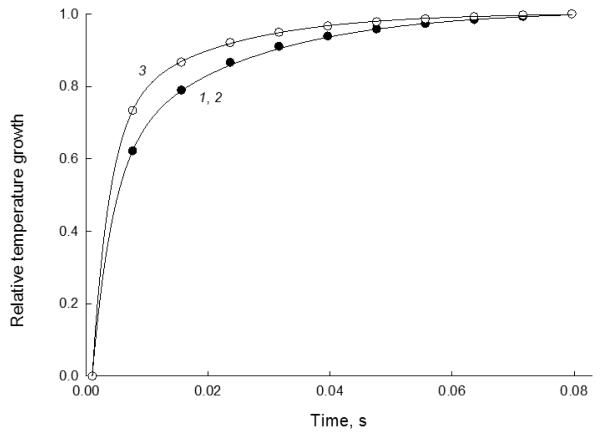

Curves of the relative temperature growth with time in the irradiated samples obtained from the transient PT thermal-lens measurements (the temperature is scaled to the maximum attained at a thermal equilibrium, the environment temperature considered as the zero point) for thermooptical heating of an aqueous solution of ferroin (1) and solutions of cyt c (III) with the concentrations of 2, 1 μM and 3, 5 μM. cw laser excitation, 514.5 nm, 40 mW.

To verify the conditions selected, we compared the slopes of the calibration curves for 0.7, 2 and 10 mm sample cuvettes and for excitation powers of 12, 60, 100, 115, and 140 mW. In all the cases, for both artificial solutions of cyt c and cyt c released from mitochondria, the slopes showed the expected ratios of 1 : 2.9 : 14.2 and 1 : 5.0 : 8.3 : 9.6 : 11.7, respectively; coefficients of correlations are above 0.9995.

As a whole, these data shows that the general methodology of analytical measurements developed for PT thermal lens measurements [69–75] can be used for trace quantification of chromophores in biological samples, and this approach can be extended to various chromophores, which was made in this study for cyt c and previously [79], for haemoglobin species.

It is important to compare the results obtained from mitochondria with the calculations for the average content of cyt c in them. From the data [77, 78], the average amount of cyt c is about 0.16 amol per mitochondrion. Therefore, the above limit of detection can be recalculated as cyt c released from approximately 3.1 × 108 mitochondria per mL or as low as 80 amol or 3000 organelles in the signal-generation zone of 90 nL. Apart from it, the calibration for mitochondria can be built in units of the mass of protein released from mitochondria. The limit of detection of PT technique in the cw mode in these units is 3.1 μg of protein/mL, which corresponds to cyt c released from approximately 2.7 × 108 mitochondria per mL (2500 organelles in the detection zone). Thus, these values are in relatively good agreement.

To improve the limits of detection, we increased power of the excitation laser (600 mW) and decreased the optical pathlength of 0.1 mm (measurements in quartz capillaries), the limit of detection of cyt c released from mitochondria under these conditions is 1 nmol/L, which correspond to the release of the protein from 40 mitochondria in the signal-generating zone. This could be the estimate of the possibilities of the cw PT thermal-lens technique in the quantification of chromophore proteins as no specific feature of cyt c apart from its spectrochemical parameters are taken into account.

However, the cw PT thermal-lens technique still shows some limitations in the case of heterogeneous solutions: even for mitochondria solutions, the reproducibility degrades (Table 1), and it is not quite applicable to cells. To keep a high signal-to-noise ratio, the signal-generating volume in this schematic cannot be diminished significantly, thus, single-mitochondrion detection by this technique is doubtful as all the cyt c is concentrated in a mitochondrion and is not spread in solution (0.16 amol per 1×10−15 L, i.e. 160 μM local concentration of cyt c, which is below the above limit of detection. This can be overcome with a transient PT technique with a pulsed laser with much shorter excitation times, thus completely unaffected with the scattering and microscopic measurements that provide a way to gather the PT signal from a volume corresponding to low ensembles or even single particles.

Thus, a pulsed PT microscope due to superior locality of detection is capable to obtain PT signal from a single mitochondrion with a high signal-to-noise ratio (Figure 3C). Experimentally observed signal-to-noise ratio is higher than 12 for a single mitochondrion for one laser pulse; thus, the threshold sensitivity of PTM is as at least 160 zmol of cyt c per single mitochondrion. This limit of detection corresponds to 13 zmol of cyt c in the ca. 1 fL detected volume and is in a very good correlation with previously published results [52] for PT microscopic detection with chopped cw excitation. In our transient PTM, the detected volume is determined in the lateral direction by the beam diameter of a strongly focused excitation laser (~700 nm) and in the axial direction by the size of mitochondria (0.7–1.5 μm) because ‘thin’ cell on a substrate make it possible to observe a single mitochondrion at least near a cell margin. Further improvements in sensitivity to a sub-zeptomole level is expected with averaging of many PT signals from the same mitochondrion (from 100 to 104 with a current excitation pulse rate of 10 Hz, and available lasers with pulse rates up to 104 Hz) and further decreasing detection volume to the optical diffraction limits.

3.4. Mitochondria release and real-sample characterization by cw PT thermal-lens technique

Mitochondria-related apoptosis is attributed to the early release of various pro-apoptotic proteins including cyt c [10–12]. The main way for such a release is the phenomenon of mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) and, thus, the screening of anti- or pro-apoptotic compounds mainly performed on the basis of standard methods of MPT determination (mitochondrial membrane potential and swelling of mitochondria) [6, 8]. But, in particular for the brain mitochondria, MPT is not the only way for the release of cyt c. Thus, it is important to develop a method for estimating cyt c release from mitochondria suitable for high-throughput screening. In this paper, we determined cyt c released from mitochondria using PT techniques. We selected the techniques that already proved themselves in applied biophysical studies [76, 77] to verify the PT data. To get the maximum precision of PT measurements, all the samples were proportionally and equally diluted to achieve PT thermal-lens signal ca. 0.1 [70]. The results are summarized in Table 1.

First, all the data are characterized by almost the same and high reproducibility, the highest relative standard deviation of 7% for samples #2 and #3. The measurements of cyt c released from mitochondria are characterized by higher RSD, and the concentration of cyt c with due account of dilution, 4.2 ± 0.9 mg/mL (Table 1) is in agreement with the concentration of the protein in mitochondria obtained by the independent method and stated in the Materials and Methods section (4.0 mg/mL).

Next, the results for all six sample types are in accordance with the absorbance measurements (Figure 4B). However, sample types #2 and #3 are less affected by scattering (Figure 4B) and show lower increase in the cyt c concentration compared to the look of their absorbance spectra. Thus, along with the high precision of PT results, we can assume that PT gives a picture of a higher absorption due to the release of cyt c from mitochondria, while a higher signal increase in sample types #2 and #3 can result from high scattering of mitochondria body fragments appearing in solution during their destruction and the release of cyt c.

The results show that suspending mitochondria with sucrose (sample types #2 and #3) results in a higher release of cyt c compared to KCl suspensions (sample types #4 and #5), which is evident from the increase in PT signal amplitude over the signals of corresponding reference samples #1 and #4. The PT data shows that the cyt c release due to induction of MPT is more effective by the treatment with KH2PO4 followed by CaCl2 (sample types #2 and #5), rather than vice versa (CaCl2 followed by KH2PO4 (sample types #3 and #6). Actually, an increase in the cyt c release of KCl-suspended sample is statistically insignificant. These data are in good agreement with the finding of the previous papers [76, 77] although PT monitoring of cyt c release was achieved for 100-fold lower concentrations of the chromophore and with much better precision against scattering backgrounds than conventional absorbance measurements. Thus, PT measurements in a cw mode showed the possibility to simultaneously determine trace amounts of cyt c from complicated samples like mitochondria hydrolyzates and distinguishing it from aqueous solutions. The analysis time and precision makes it expedient for high-throughput screening of cyt c based samples.

3.5. Determination of thermophysical parameters of cytochrome c solutions with transient PT thermal-lens techniques

Thus, the use of cw PT mode did not reveal any changes in the spectra of cyt c (Figure 5). However, the experimental data of transient measurements, Eq. (2), show a change in the PT characteristic time tc (Eq. (4)), compared to neat aqueous solutions of low-molecular dyes like ferroin or other metal chelates. The value of tc for 5 μM of cyt c is 5.0 ± 0.1 ms (Figure 7), while its value for aqueous solutions is 6.3 ± 0.1 ms (which correlates with the calculations of DT of water). In other words, there is a faster development of the thermal lens in a mitochondrial solution, which correlates with the behavior of hemoglobin solutions within the same concentration range reported previously [79]. Such phenomena appear when a large molecule (of a protein) is in the signal-generation zone. In this case, the PT heating of the irradiated zone is higher than in the case of a neat aqueous solution, which results in a quicker temperature rise. This behavior is also confirmed by a similar (and stronger) effect of hot zones in PT images of erythrocytes [56] and nanoparticles [50, 80].

This behavior can be used for qualitatively distinguishing the high-molecular-weight (protein) chromophores from aqueous solutions of low-molecular dyes. The data of Figure 7 show that a change in transient curves becomes significant for 5 μM of cyt c, i.e. the level used for the determination of cyt c from mitochondria (Table 1), which can be used as a figure of merit of such determination. However, within the frames of this study, the transient curves for mitochondria hydrolyzates were more distorted than free cyt c samples, and the quantitative determination was not possible.

Another application of the cw PT transient curves is that a change in the characteristic time is governed by thermal diffusivity DT, [74] thus, it can be used for the determination of its change. Next, knowing the overall value for the measured sample it can be used with Eqs. (9) and (10) for determining the thermophysical parameters of the protein (if its concentration and molecule size are known) or the determination of the actual cluster size (provided its concentration and thermophysical parameters are known). If the steady-state signal is measured (which is hardly missed in such experiments), the problem becomes even simpler. The calculations of the theoretical increase in E0 is possible with the multipoint approach (9) and (10). The calculations give estimations of E0 and DT as 0.20 mW−1 and (1.3 ± 0.1) 10−7 m2/s, which differ significantly from that of water [74].

Contrary to cw excitation, a comparison of the conventional absorbance spectrum of cyt c with pulsed PT excitation (Figure 5) shows a significant change in spectra with the signal enhancement APT. This can be accounted for a change in the real value of E0 for pulsed PT measurements as for nanosecond pulses, the development of PT signal occurs not in water, but in the local protein-filled zone surrounding the chromophore, or owing to nonlinear effects due to relatively high level of laser fluence. Thus, it confirms our findings for cw transient signal, as in cw PT measurements the effect of the protein affects only the first part of the signal curve through DT, while in short pulses with higher power density it affects the whole signal development through E0. This hypothesis is also confirmed by the fact that not all the spectrum lies higher, but only the part in 520–560 nm, i.e. within the location of main absorption bands in this spectral range.

The comparison of pulsed PT measurements of the spectra of cyt c solutions and individual cells obtained at different wavelengths of the excitation laser (Figure 5) revealed that the latter show a quite good correlation with the conventional spectrum of the reduced form cyt c (Figure 4A), at least in the spectral range of 530–550 nm. This is in agreement with the previous data on the state of cyt c in intact mitochondria [78]. Also, Figure 5 shows a much higher increase in the APT compared to the same calculations for free cyt c. This confirms our assumptions that the thermophysical properties of the local environment of intracellular chromophores may determine the magnitude of the PT signal in pulsed measurements. As the thermal diffusivity in cells and thermal conductivity is lower and thermal capacity (governing the dn/dT value in (3)) is higher, than in water and proteins [81] the overall increase is much higher than in aqueous solutions and free cyt c solutions. Still, noteworthy is the fact that the increase from the conventional spectrum is significant in the same range as above when the main absorption bands of cyt c are located. In the valley part of the absorption spectrum (450–510 nm) the PT spectra APT(λ) and absorbance spectra A(λ) differ insignificantly.

In the frames of the multipoint approach, Eqs. (9) and (10), it is possible to estimate the irregularities of the temperature (and, thus, of refractive-index) profile for a discrete number of cells (or mitochnodria) at a laser beam waist and easily change the concentration or size parameters for the system. Theoretical calculations show a good concordance with experimental results for transient and steady-state experiments for cells. Like in the previous case, the calculations for the pulsed mode give estimations of E0 and DT as 0.3 mW−1 and (1.3 ± 0.1) 10−7 m2/s, which is higher than in the previous case of mitochondria outside the cells, which confirms the calculations for the cw PT mode.

As a whole, retaining the high sensitivity of determination, pulsed PT technique provides a more precise and multiparametric estimation of thermophysical properties of cells and proteins with a locality corresponding to single-cell analysis.

4. Conclusions

As many cellular components are weakly fluorescent, and some are low-scattering and low-refractive, existing optical imaging techniques for studying these structures in their native state without staining are limited (see Introduction). Fluorescent microscopy is currently the most powerful optical imaging technique to study cellular proteins with high resolution and specificity. Despite progress in developing fluorescent tags, however, labeling procedure may still alter biological properties of targeted structures and interfere with cellular activity (e.g., see discussion in [44, 53, 62]). In this work, we demonstrated the capability of label-free multifunctional PT techniques combining high resolution (350 nm) PTM (photothermal microscopy) and spectrometry for detection of cyt c in isolated mitochondria with sensitivity comparable with fluorescent microscopy.

More important is that PTM and PT spectroscopy, which was previously used separately—for spectroscopic studies of homogenous absorbing samples with no spatial data or imaging of individual cells with a limited spectroscopic information—were extended in this work theoretically and partly experimentally on their joint use as imaging and spectroscopy modalities with focus on multi (discrete) absorbing point samples like clustered cyt c in mitochondria [55]. The sensitivity and precision of the cw mode is suitable for trace analytical measurements in laboratory real samples like mitochondria hydrolyzates or extracts, and can be readily enhanced by similar pulsed-excitation schematics. The achieved sensitivity of detection and quantification cyt c detection in mitochondria and released from them is significantly increased compared to conventional absorption spectroscopy. The potential application of this technique/approach may include spectral identification and quantitative detection of highly localized cellular proteins in single cells in vitro and in vivo in batch and flow condition [60] in blood, lymph, and other biological liquids, as PT immunoaggregation assays [56], detection of biomolecules labeled with conventional organics labels or advanced nanoparticles [38, 80] with potential to detect single molecules. And these measurements can be complemented with PT imaging.

At current schematic, the PT image represents a two-dimensional (2D) depth-integrated PT signal (absorption) distribution in the irradiated volume and correlates with conventional diffraction-limited optical transmission images. The 3D PT imaging of biological objects with can be developed by using the principle of confocal PT microscopy [83] with a potential to achieve an axial resolution up to 1–2 μm or PT tomography as rough analogy to PA tomography [37, 40, 84] (we introduced PA tomography in 1989 to monitor laser beam profiles [84]). Further studies will include far-field PT microscopy beyond diffraction limit [54], fast (millisecond scale) imaging with a high pulse rate laser [85], label-free PT Raman microscopy [63] providing chemical specificity for non- or weakly absorbing in near-infrared range cellular structures with Raman-active vibrational modes (e.g., lipids), and a combination of three parts of PT diagnostics –– imaging, identification, and quantification –– in a single instrument.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, grant numbers 10-03-01018-a and 09-03-92102-YAF_a (M.A. P and D.A. N); the National Institute of Health grant numbers R01EB000873, R01CA131164, R01 EB009230, and R21CA139373 (V. P. Z), the National Science Foundation grant numbers DBI-0852737 (V. P. Z).

Biography

Anton Brusnichkin is currently the freelance researcher at the Chemistry faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. He graduated from the Chemistry faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. His scientific interests lie in the biological applications of photothermal and chemiluminescence spectroscopy for proteins and organelles. He studied the conditions of formation and properties of complexes of heme proteins with carbon monoxide and nitrogen monoxide, photoacoustic studies of disperse systems like lipopolysaccharides and metal nanoparticles.

Dmitry Nedosekin is the Biomedical Engineer of the Phillips Classic Laser & Nanomedicine Laboratories. He graduated from the Chemistry faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University and received a Ph.D. degree on Analytical Chemistry. He completed a doctoral fellowship on the development of thermal lens detection for capillary electrophoresis at the Chemistry department of Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany (2004–2005). His scientific interests lie in the biological applications of photothermal and photoacoustic spectroscopy.

Ekaterina Galanzha is one of the leading scientists with the Phillips Classic Laser & Nanomedicine Laboratories and an Assistant Professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in the USA. She received her M.D., Ph.D. and D.Sc. degrees from Saratov Universities in Russia. Her interdisciplinary expertise includes cell biology, experimental medicine, biophotonics and nanobiotechnology with a focus on lymphatic and cancer research. She is a coinventor of the in-vivo multicolor photoacoustic lymph and blood flow cytometry.

Yuri Vladimirov is the chair of the division of the Medicinal Biophysics, professor of Biophysics of the Faculty of Basic Medicine of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University and head of the laboratory of protein crystallography in the Institute of Crystallography of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Prof. Vladimirov graduated from the Biological faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. His scientific interests involve the studies of luminescence (fluorescence and low-temperature phosphorescence) of proteins. He discovered the intrinsic (ultra-weak) luminescence in the course of biochemical reactions. He was one of the inventors of the method of fluorescent probes for studying membrane structures and lipoproteins and deciphered the molecular basics of the therapeutic action of the laser radiation.

Elena Shevtsova graduated from the Biological faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University and received a Ph.D. degree from the Institute of Physiologically Active Compounds of the Russian Academy of Sciences (PAC RAS). Now she is a leading researcher at the Laboratory of Neurochemistry at the IPAC RAS. The main research interests of Dr. Shevtsova deal with the investigations of role of mitochondria in the neurodegeneration, the search for new targets for neuroprotection and the development of the respective screening methods.

Mikhail Proskurnin is the Associate Professor at the Chemistry faculty of M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University. He graduated from and received his Ph.D. and D.Sc. degrees from M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, and was a guest scientist in Tokyo University (1999–2000) and Scientific Center Karlsruhe (FZK, Germany) in 2002. He is the member of the Bureau of the Scientific Council of Analytical Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The scientific interests of Dr. Proskurnin lie in the development of photothermal spectroscopy as a method of analytical chemistry and applied biological studies and its combinations with other state-of-the-art methods.

Vladimir Zharov is the director of the Phillips Classic Laser & Nanomedicine Laboratories and a Professor of Biomedical Engineering (BME) at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, USA. He received his Ph.D. and D.Sc. degrees from Moscow State Technical University (MSTU), completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and served as the Chairman of BME department at MSTU. He is one of the pioneers of photoacoustic spectroscopy and the inventor of photoacoustic tweezers, pulse nanophotothermolysis of infections and cancer, and in-vivo multicolor photoacoustic flow cytometry.

References

- 1.Belikova NA, Vladimirov YA, Osipov AN, Kapralov AA, Tyurin VA, Potapovich MV, Basova LV, Peterson J, Kurnikov IV, Kagan VE. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4998–5009. doi: 10.1021/bi0525573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karu T. J Photoch Photobio B. 1999;49:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00219-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karu TI, Afanasyeva NI, Kolyakov SF, Pyatibrat LV, Welser K. IEEE J Sel Topics Quant Electron. 2001;7:982–988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desagher S, Martinou JC. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein JC, Muñoz-Pinedo C, Ricci JE, Adams S, Kelekar A, Schuler M, Tsien R, Green DR. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:453–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan SD, Stern DM. Int J Exp Pathol. 2005;86:161–171. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2005.00427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gourley PL, Hendricks JK, McDonald AE, Copeland RG, Barrett KE, Gourley CR, Singh KK, Naviaux RK. Technol Cancer Res T. 2005;4:585–592. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gourley PL, Hendricks JK, McDonald AE, Copeland RG, Barrett KE, Gourley CR, Naviaux RK. Biomed Microdevices. 2005;7:331–339. doi: 10.1007/s10544-005-6075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mather M, Rottenberg H. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2000;273:603–608. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desagher S, Martinou JC. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naomi H, Naoya F, Takashi T. Oncogene. 2003;22:5579–5585. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein JC, Waterhouse NJ, Juin P, Evan GI, Green DR. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:156–162. doi: 10.1038/35004029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. http://www.medcompare.com/details/46767/Mitochondria-ELISA-Test-Kit.html.

- 14. http://www.mitosciences.com/western_blotting.html.

- 15.Picklo MJ, Zhang J, Nguyen VQ, Graham DG, Montine TJ. Anal Biochem. 1999;276:166–170. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs A, Worwood M, editors. Iron in Biochemistry and Medicine. Academic Press; London and New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoppe W, Lohmann W, Markl H, Ziegler H, editors. Biophysics. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg New York Tokyo: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vo-Dinh Tuan., editor. Biomedical Photonics. CRC Press; London, New York, Washington D.C.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuchin VV, editor. Optical Biomedical Diagnostics. SPIE Press Bellingham; Washington: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zharov VP, Lapotko DO. IEEE J Sel Topics Quant Electron. 2005;11:733–751. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chance B, Hess B. Science. 1959;129:700–708. doi: 10.1126/science.129.3350.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorell B, Chance B. Exp Cell Res. 1960;20:43–55. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(60)90220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorell B, Chance B, Legallais V. J Cell Biol. 1965;26:741–746. doi: 10.1083/jcb.26.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kolyakov SF, Afanasyeva NI. J Photoch Photobio B. 2005;81:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Funk RH, Hoper J, Dramm P, Hofer A. Physiol Meas. 1998;19:225–233. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/19/2/010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasch P, Pacifico A, Diem M. Biopolymers. 2002;67:335–338. doi: 10.1002/bip.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barty A, Nugent KA, Paganin D, Roberts A. Opt Lett. 1998;23:817–819. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boustany NN, Drezek R, Thakor NV. Biophys J. 2002;83:691–700. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73937-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Li X, Kim YL, Backman V. Opt Lett. 2005;30:2445–2447. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.002445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chalut KJ, Ostrander JH, Giacomelli MG, Wax A. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1199–1204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uzunbajakava N, Lenferrink A, Kraan Y, Vremsen G, Greve J, Otto C. Biophys J. 2003;84:3968–3981. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramser K, Logg K, Goksor M, Enger J, Kall M, Hanstorp D. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:593–600. doi: 10.1117/1.1689336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nithipatikom K, McCoy MJ, Hawi SR, Nakamoto K, Adar F, Campbell WB. Anal Biochem. 2003;322:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Dijk MA, Tchebotareva AL, Orrit M, Lippitz M, Berciaud S, Lasne D, Cognet L, Lounis B. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:3486–3495. doi: 10.1039/b606090k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka Y, Sato K, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Okano T, Kitamori T. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cognet L, Berciaud S, Lasne D, Lounis B. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2288–2294. doi: 10.1021/ac086020h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang LV, editor. Photoacoustic imaging and spectroscopy. CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JW, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Moon HM, Zharov VP. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galanzha EI, Kokoska MS, Shashkov EV, Kim JW, Tuchin VV, Zharov VP. J Biophotonics. 2009;2:528–539. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200910046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ntziachristos V, Razansky D. Chem Rev. 2010 Apr 14; doi: 10.1021/cr9002566. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zharov VP, Letokhov VS. Laser Optoacoustic Spectroscopy. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wickramasinghe HK, Bray RC, Jipson V, Quate CF, Salcedo JR. Appl Phys Lett. 1978;33:923–925. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapotko DO, Kuchinsky G, Potapnev M, Pechkovsky D. Cytometry. 1996;24:198–203. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19960701)24:3<198::AID-CYTO2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lapotko D, Romanovskaya T, Kutchinsky G, Zharov V. Cytometry. 1999;37:320–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapotko D. Proc SPIE. 2000;3916:268–277. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lapotko DO, Romanovskaya T, Zharov VP. J Biomed Opt. 2002;7:425–434. doi: 10.1117/1.1481902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lapotko DO, Romanovskaya TR, Shnip A, Zharov VP. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;31:53–63. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lapotko DO, Zharov VP. 7230708 B2. US patent. priority date 2000, published 2007.

- 49.Zharov VP, Lapotko DO. Rev Sci Instrum. 2003;74:785–788. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zharov V, Galitovsky V, Viegas M. Appl Phys Lett. 2003;83:4897–4899. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lapotko DO, Zharov VP. Laser Surg Med. 2005;36:22–30. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamaki E, Sato K, Tokeshi M, Sato K, Aihara M, Kitamori T. Anal Chem. 2002;74:1560–1564. doi: 10.1021/ac011092t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zharov VP, Galitovskiy V, Lyle CS, Chambers TC. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:06403. doi: 10.1117/1.2405349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zharov V. Opt Lett. 2003;28:1314–1316. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zharov VP, Galitovsky V, Chowdhury P. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:044011. doi: 10.1117/1.1990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zharov VP, Galanzha EI, Tuchin VV. Cytometry A. 2007;71:191–206. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zharov V, Galanzha E, Tuchin V. Proc SPIE. 2004;5320:256–263. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zharov VP, Galanzha EI, Tuchin VV. Opt Lett. 2005;30:628–630. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zharov VP, Galanzha EI, Tuchin VV. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:51502. doi: 10.1117/1.2060567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zharov VP, Galanzha EI, Tuchin VV. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:916–932. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Tuchin VV, Zharov VP. Cytometry A. 2008;73A:884–894. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lasne D, Blab GA, Giorgi FD, Ichas F, Lounis B, Cougnet L. Opt Express. 2007;15:14184–93. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.014184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shashkov EV, Galanzha EI, Zharov VP. Opt Express. 2010;18:6929–44. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.006929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lapotko DO. Cytometry A. 2004;58A:111–119. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galitovskiy V, Chowdhury P, Zharov VP. Life Sci. 2004;75:2677–2687. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zharov VP, Viegas M, Soderberg L. Proc. SPIE. 2005;5697:271–281. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brusnichkin AV, Marikutsa AV, Proskurnin MA, Proskurnina EV, Osipov AN, Vladimirov Yu.A. Moscow Univ Chem Bull. 2009;63:338–342. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lapotko DO, Romanovskaya T, Gordiyko E. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;75:519–526. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0519:pmorso>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Proskurnin MA, Pirogov AV, Slyadnev MN, Borzenko AG, Zolotov Yu.A. J Anal Chem (Russ.) 2004;59:828–833. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Proskurnin MA, Kuznetsova VV. Anal Chim Acta. 2000;418:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luk’yanov AY, Vladykin GB, Novikov MA, Yashin YI. J. Anal. Chem. (Russ.) 1999;54:633–636. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Proskurnin MA, Abroskin AG, Radushkevich D.Yu. J Anal Chem (Rus) 1999;54:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abroskin AG, Belyaeva TV, Filichkina VA, Ivanova EK, Proscurnin MA, Savostina VM, Barbalat Yu.A. Analyst. 1992;117:1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bialkowski SE. Photothermal Spectroscopy Methods for Chemical Analysis. Wiley; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nedosekin DA, Kononets M.Yu., Proskurnin MA. Appl Opt. 2005;44:6296–6306. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.006296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shevtzova EF, Kireeva EG, Bachurin SO. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2001;132:652–656. doi: 10.1023/a:1014559331402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bachurin SO, Shevtsova EP, Kireeva EG, Oxenkrug GF, Sablin SO. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;993:334–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gear RLA, Bednarek JM. J Cell Biol. 1972;54:325–345. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brusnichkin AV, Nedosekin DA, Ryndina ES, Proskurnin MA, Gleb E.Yu., Lapotko DO, Vladimirov Yu.A., Zharov VP. Moscow Univ Chem Bull. 2009;64:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brusnichkin AV, Nedosekin DA, Proskurnin MA, Zharov VP. Appl Spectrosc. 2007;61:1191–1201. doi: 10.1366/000370207782597175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Poppendiek HF, Randall R, Breeden JA, Chambers JE, Murphy JR. Cryobiology. 1967;3:318–327. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thanh NTK, Rees JH, Rosenzweig Z. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2002;374:1174–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00216-002-1599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zharov VP, Galanzha EI, Ferguson S, Tuchin VV. Proc SPIE. 2005;5697:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zharov VP, Simanovsky YO. Sov Phys Acoust. 1989;35:556–558. [Google Scholar]

- [85].Nedosekin DA, Sarimollaoglu M, Shashkov EV, Galanzha EI, Zharov VP. Opt. Express. 2010;18:8605–8620. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.008605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]