Abstract

It is well established that autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have a strong genetic component. However, for at least 70% of cases, the underlying genetic cause is unknown1. Under the hypothesis that de novo mutations underlie a substantial fraction of the risk for developing ASD in families with no previous history of ASD or related phenotypes—so-called sporadic or simplex families2,3, we sequenced all coding regions of the genome, i.e. the exome, for parent-child trios exhibiting sporadic ASD, including 189 new trios and 20 previously reported4. Additionally, we also sequenced the exomes of 50 unaffected siblings corresponding to these new (n = 31) and previously reported trios (n = 19)4, for a total of 677 individual exomes from 209 families. Here we show de novo point mutations are overwhelmingly paternal in origin (4:1 bias) and positively correlated with paternal age, consistent with the modest increased risk for children of older fathers to develop ASD5. Moreover, 39% (49/126) of the most severe or disruptive de novo mutations map to a highly interconnected beta-catenin/chromatin remodeling protein network ranked significantly for autism candidate genes. In proband exomes, recurrent protein-altering mutations were observed in two genes, CHD8 and NTNG1. Mutation screening of six candidate genes in 1,703 ASD probands identified additional de novo, protein-altering mutations in GRIN2B, LAMC3, and SCN1A. Combined with copy number variant (CNV) data, these results suggest extreme locus heterogeneity but also provide a target for future discovery, diagnostics, and therapeutics.

We selected 189 autism trios from the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC)6, which included males significantly impaired with autism and intellectual disability (ID) (n = 47), a female sample set (n = 56) of which 26 were cognitively impaired, and samples chosen at random from the remaining males in the collection (n = 86) (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). In general, we excluded samples known to carry large de novo CNVs2. Exome sequencing was performed as described previously4, but with an expanded target definition (Methods). We achieved sufficient coverage for both parents and child to call on average 29.5 Mbp of haploid exome coding sequence (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, we performed copy number analysis on 122 of these families, using a combination of the exome data, array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), and genotyping arrays, thereby providing a more comprehensive view of rare variation.

In the 189 new probands, we validated 248 de novo events, 225 single nucleotide variants (SNVs), 17 small indels, and six CNVs (Supplementary Table 2). These included 181 nonsynonymous changes, of which 120 were classified as severe based on sequence conservation and/or biochemical properties (Methods, Supplementary Table 3). The observed point mutation rate in coding sequence was ~1.3 events per trio or 2.17 × 10−8 per base per generation, in close agreement with our previous observations4, yet in general, higher than previous studies suggesting increased sensitivity (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4)7. We also observed complex classes of de novo mutation including: five cases of multiple mutations in close proximity; two events consistent with paternal germline mosaicism (i.e. where both siblings contained a de novo event observed in neither parent); and nine events showing a weak minor allele profile consistent with somatic mosaicism (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2,3).

Of the severe de novo events, 28% (33/120) are predicted to truncate the protein. The distribution of synonymous, missense, and nonsense changes corresponds well with a random mutation model7 (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). However, the difference in nonsense rates between de novo and rare singleton events (not present in 1,779 other exomes) is striking (4:1) and suggests strong selection against new nonsense events (Fisher’s exact text p < 0.0001). In contrast with a recent report8, we find no significant difference in mutation rate between affected and unaffected individuals; however, we do observe a trend toward increased nonsynonymous rates in probands, consistent with the finding of Sanders and colleagues9 (Supplementary Tables 1,2).

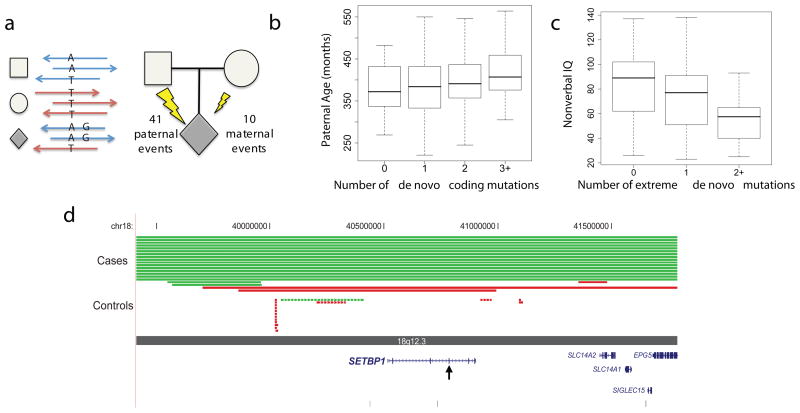

Given the association of ASD with increased paternal age5 and our previous observations4, we used molecular cloning, read-pair information, and obligate carrier status to identify informative markers linked to 51 de novo events and observed a marked paternal bias (41:10; binomial p < 1.4 × 10−5; Fig. 1a and Supplementary Tables 3,5). This provides strong direct evidence that the germline mutation rate in protein-coding regions is, on average, substantially higher in males. A similar finding was recently reported for de novo CNVs10. In addition, we observe that the number of de novo events is positively correlated with increasing paternal age (Spearman’s rank correlation = 0.19; p-value < 0.008; Fig. 1b). Together, these observations are consistent with the hypothesis that the modest increased risk for children of older fathers to develop ASD5 is the result of an increased mutation rate.

Figure 1. De novo mutation events in autism spectrum disorder.

a Haplotype phasing using informative markers shows a strong parent-of-origin bias with 41/51 de novo events occurring on the paternally inherited haplotype. b and c, Box and whisker plots for 189 SSC probands. b, The paternal estimated age at conception versus the number of observed de novo point mutations (0, n = 53; 1, n = 65; 2, n = 44; 3+, n = 27). c, Decreased nonverbal IQ is significantly associated with an increasing number of “extreme” mutation events (0, n = 138; 1, n = 41; 2+, n = 10), both with and without CNVs (Supplementary Discussion). d, Browser images showing CNVs identified in del(18)(q12.2q21.1) syndrome region. Truncating point mutation in SETBP1 occurs within the critical region, identifying the likely causative locus. Each red (deletion) and green (duplication) line represents an identified CNV in cases (solid lines) versus controls (dashed lines), with arrowheads showing point mutation.

Using sequence read-depth methods in 122 of the 189 families, we scanned ASD probands for either de novo CNVs or rare (<1% of controls), inherited CNVs. Individual events were validated by either array CGH or genotyping array (Methods). We identified 76 events in 53 individuals, including six de novo (median size 467 kbp) and 70 inherited (median size 155 kbp) CNVs (Supplementary Table 6). These include disruptions of EHMT1 (Kleefstra Syndrome, MIM 610253), CNTNAP4 (reported in children with developmental delay and autism11), and the 16p11.2 duplication (MIM 611913) associated with developmental delay, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

We performed a multivariate analysis on nonverbal IQ (NVIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ), and the load of “extreme” de novo mutations; extreme defined as point mutations that truncate proteins, intersect Mendelian or ASD loci (n = 57), or de novo CNVs that intersect genes (n = 5) (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Discussion). NVIQ, but not VIQ, decreased significantly (p < 0.01) with increased number of events. Covariant analysis of the samples with CNV data, showed this finding was strengthened, but not exclusively driven, by the presence of either the de novo CNV or additional rare CNV (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Among the 120 de novo truncating and severe missense events, we identified 62 top ASD risk contributing mutations based on the deleteriousness of the mutations, functional evidence, or previous studies (Table 1). Probands with these mutations spanned the range of IQ scores, with only a modest nonsignificant trend toward individual’s comorbid with ID (Supplementary Fig. 1,6). We observed recurrent, protein-disruptive mutations in two genes, NTNG1 (netrin G1) and CHD8 (chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8). Given their locus-specific mutation rates, the probability of identifying two independent mutations in our sample set is low (uncorrected, NTNG1: p < 1.2 × 10−6, CHD8: p < 6.9 × 10−5) (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 8 and Online Methods). NTNG1 is a strong biologic candidate given its role in laminar organization of dendrites and axonal guidance12 and was also reported disrupted by a de novo translocation in a child with Rett syndrome, without MECP2 mutation13. Both de novo mutations identified here are missense (p.TYR23CYS and p.THR135ILE) at highly conserved positions predicted to disrupt protein function, although there is evidence of mosaicism for the former mutation (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Top de novo ASD risk contributing mutations*

| Proband | NVIQ | Candidate Gene | AA change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12225.p1 | 89 | ABCA2 | p.VAL1845MET |

| 11653.p1 | 44 | ADCY5 | p.ARG603CYS |

| 12130.p1 | 55 | ADNP | frameshift indel |

| 11224.p1 | 112 | AP3B2 | p.ARG435HIS |

| 13447.p1 | 51 | ARID1B | frameshift indel |

| 13415.p1 | 48 | BRSK2 | 3n indel |

| 14292.p1 | 49 | BRWD1 | frameshift indel |

| 11872.p1 | 65 | CACNA1D | p.ALA769GLY |

| 11773.p1 | 50 | CACNA1E | p.GLY1209SER |

| 13606.p1 | 60 | CDC42BPB | p.ARG764TERM |

| 12086.p1 | 108 | CDH5 | p.ARG545TRP |

| 12630.p1 | 115 | CHD3 | p.ARG1818TRP |

| 13733.p1 | 68 | CHD7 | p.GLY996SER |

| 13844.p1 | 34 | CHD8 | p.GLN959TERM |

| 12752.p1 | 93 | CHD8 | frameshift indel |

| 13415.p1 | 48 | CNOT4 | p.ASP48ASN |

| 12703.p1 | 58 | CTNNB1 | p.THR551MET |

| 11452.p1 | 80 | CUL3 | p.GLU246TERM |

| 11571.p1 | 94 | CUL5 | p.VAL355ILE |

| 13890.p1 | 42 | DYRK1A | splice site |

| 12741.p1 | 87 | EHD2 | p.ARG167CYS |

| 11629.p1 | 67 | FBXO10 | p.GLU54LYS |

| 13629.p1 | 63 | GPS1 | p.ARG492GLN |

| 13757.p1 | 91 | GRINL1A | 3n indel |

| 11184.p1 | 94 | HDGFRP2 | p.GLU83LYS |

| 11610.p1 | 138 | HDLBP | p.ALA639SER |

| 11872.p1 | 65 | KATNAL2 | splice site |

| 12346.p1 | 77 | MBD5 | frameshift indel |

| 11947.p1 | 33 | MDM2 | p.GLU433LYS/p.TRP160TERM |

| 11148.p1 | 82 | MLL3 | p.TYR4691TERM |

| 12157.p1 | 91 | NLGN1 | p.HIS795TYR |

| 11193.p1 | 138 | NOTCH3 | p.GLY1134ARG |

| 11172.p1 | 60 | NR4A2 | p.TYR275HIS |

| 11660.p1 | 60 | NTNG1 | p.THR135ILE |

| 12532.p1 | 110 | NTNG1 | p.TYR23CYS |

| 11093.p1 | 91 | OPRL1 | p.ARG157CYS |

| 13793.p1 | 56 | PCDHB4 | p.ASP555HIS |

| 11707.p1 | 23 | PDCD1 | frameshift indel |

| 12304.p1 | 83 | PSEN1 | p.THR421ILE |

| 11390.p1 | 77 | PTEN | p.THR167ASN |

| 13629.p1 | 63 | PTPRK | p.ARG784HIS |

| 13333.p1 | 69 | RGMA | p.VAL379ILE |

| 13222.p1 | 86 | RPS6KA3 | p.SER369TERM |

| 11257.p1 | 128 | RUVBL1 | p.LEU365GLN |

| 11843.p1 | 113 | SESN2 | p.ALA46THR |

| 12933.p1 | 41 | SETBP1 | frameshift indel |

| 12565.p1 | 79 | SETD2 | frameshift indel |

| 12335.p1 | 47 | TBL1XR1 | p.LEU282PRO |

| 11480.p1 | 41 | TBR1 | frameshift indel |

| 11569.p1 | 67 | TNKS | p.ARG568THR |

| 12621.p1 | 120 | TSC2 | p.ARG1580TRP |

| 11291.p1 | 83 | TSPAN17 | p.SER75TERM |

| 11006.p1 | 125 | UBE3C | p.SER845PHE |

| 12161.p1 | 95 | UBR3 | frameshift indel |

| 12521.p1 | 78 | USP15 | frameshift indel |

| 11526.p1 | 92 | ZBTB41 | p.TYR886HIS |

| 13335.p1 | 25 | ZNF420 | p.LEU76PRO |

| CNV | |||

| Proband | Candidate Gene | Type | |

| 13335.p1 | 25 | CHRNA7 | duplication |

| 13726.p1 | 59 | CNTNAP4 | deletion |

| 12581.p1 | 34 | CTNND1 | deletion |

| 11928.p1 | 66 | EHMT1 | deletion |

| 13815.p1 | 56 | TBX6 | duplication |

Top candidate mutations based on severity and/or supporting evidence from the literature.

CHD8 has not previously been associated with ASD and codes for an ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factor that plays a significant role in the regulation of both beta-catenin and p53 signaling14,15. We also identified de novo missense variants in CHD3 as well as CHD7 (CHARGE syndrome, MIM 214800), a known binding partner of CHD816. ASD has been found in as many as two-thirds of children with CHARGE, suggesting CHD7 may contribute to an ASD syndromic subtype17.

We identified 30 protein-altering de novo events intersecting with Mendelian disease loci (Supplementary Table 3) as well as inherited hemizygous mutations of clinical significance (Supplementary Table 9). The de novo mutations included truncating events in syndromic intellectual disability genes: MBD5 (mental retardation, autosomal dominant 1, MIM 156200), RPS6KA3 (Coffin-Lowry syndrome, MIM 303600), and DYRK1A (the Down Syndrome candidate gene, MIM 600855); and missense variants in loci associated with syndromic ASD, including: CHD7, PTEN (macrocephaly/autism syndrome, MIM 605309), and TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex, MIM 613254). Interestingly, DYRK1A is a highly conserved gene mapping to the Down Syndrome critical region (Supplementary Fig. 8). The proband here (13890) is severely cognitively impaired and microcephalic consistent with previous studies of DYRK1A haploinsufficiency in both patients and mouse models.

Twenty-one of the nonsynonymous de novo mutations map to CNV regions recurrently identified in children with developmental delay and ASD (Supplementary Table 10), such as MBD5 (2q23.1 deletion syndrome), SYNRG (17q12 deletion syndrome), and POLRMT (19p13.3 deletion)18. There is also considerable overlap with genes disrupted by single de novo CNVs in children with ASD (e.g. NLGN1 and ARID1D; Supplementary Table 11). Given the prior probability that these loci underlie genomic disorders, the disruptive de novo SNVs and small indels may be pinpointing the possible major effect locus for ASD-related features. For example, we identified a complex de novo mutation resulting in truncation of SETBP1 (SET binding protein 1), one of five genes in the critical region for del(18)(q12.2q21.1) syndrome (Fig. 1d), which is characterized by hypotonia, expressive language delay, short stature, and behavioral problems19. Recurrent de novo missense mutations at SETBP1 were recently reported to be causative for a distinct phenotype, Schinzel-Giedion syndrome, likely through a gain-of-function mechanism20, suggesting diverse phenotypic outcomes at this locus depending on mutation mechanism.

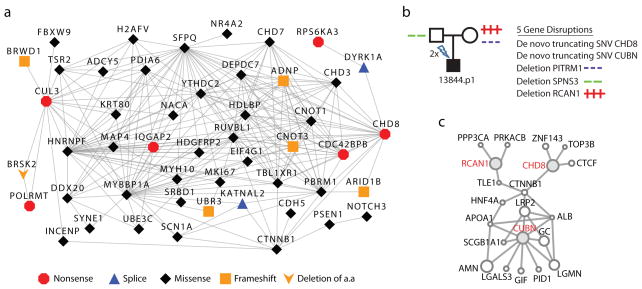

Several of the mutated genes encode proteins that directly interact, suggesting a common biological pathway. From our full list of genes carrying truncating or severe missense mutations (126 events from all 209 families), we generated a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network based on a database of physical interactions (Supplementary Table 12)21. We found 39% (49/126) of the genes mapped to a highly interconnected network wherein 92% of gene pairs in the connected component are linked by paths of three or fewer edges (Fig. 2a). We tested this degree of interconnectivity by simulation (n = 10,000 replicates; Methods and Supplementary Fig. 9) and found that our experimental network had significantly more edges (p < 0.0001) and a greater clustering coefficient (p < 0.0001) than expected by chance.

Figure 2. Mutations identified in protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks.

a The 49-gene connected component of the PPI network formed from 126 genes with severe de novo mutations among the 209 probands. b, Proband 13844 inherits three rare gene-disruptive CNVs and carries two de novo truncating mutations. c, GeneMANIA21 view of three of the affected genes (b) (red labels) which encode proteins that are part of a beta-catenin linked network. This proband is macrocephalic, impaired cognitively, and has deficits in social behavior and language development (Supplementary Discussion).

To further investigate the relevance of this network to autism, we applied degree-aware disease gene prioritization (DADA)22, based on the same PPI database to rank all genes based on their relatedness to a set of 103 previously identified ASD genes17. We found that the genes with severe mutations ranked significantly higher than all other genes (Mann-Whiney U p < 4.0 × 10−4), suggesting enrichment of ASD candidates. Furthermore, the 49 members of the connected component overwhelmingly drove this difference (Mann-Whiney U p < 1.6 × 10−8) as the unconnected members were not significant on their own (Mann-Whiney U p < 0.28), increasing our confidence that these connected gene products are likely related to ASD (Supplementary Fig. 10). Consistent with this finding, the rankings of unaffected sibling events are highly similar to the unconnected component, strengthening our confidence in the enrichment of the connected component of proband events for ASD-relevant genes.

Members of this network have known functions in beta-catenin and p53 signaling, chromatin remodeling, ubiquitination, and neuronal development (Fig. 2a). A fundamental developmental regulator observed in the network is CTNNB1 (catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88kDa), also known as beta-catenin. Interestingly, a parallel analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) shows an enrichment of upstream interacting genes of the beta-catenin pathway (8/358, p = 0.0030; Online Methods, Supplementary Table 13 and Supplementary Fig. 11). A role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in ASD was previously proposed23, based largely on the association of common variants in Engrailed 2 and WNT2, and the high rate of children with macrocephaly. It is striking that both CHD8 patients have multiple de novo disruptive missense mutations in this pathway or closely related pathways (Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Fig. 12) and both have macrocephaly.

In addition, the pathway analysis shows several other disrupted genes not identified in the PPI that are involved in common pathways, which in some cases are linked to beta-catenin (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 11). TBR1, for example, is a transcription factor that plays a critical role in the development of the cerebral cortex24. Tbr1 binds with CASK and regulates several candidate genes for ASD and intellectual disability including Grin2B, Auts2, and reelin—genes of recurrent ASD mutation, some of which are described here and in other studies4,9,11,17.

Our exome analysis of de novo coding mutations in 209 autism trios identified only two recurrently altered genes, consistent with extreme locus heterogeneity underlying ASD. This extreme heterogeneity necessitates the analysis of very large cohorts for validation. We implemented a cost-effective approach based on molecular inversion probe (MIP) technology25 for the targeted resequencing of six candidate genes in ~2,500 individuals, including 1,703 simplex ASD probands and 744 controls. Four of these candidates (FOXP1, GRIN2B, LAMC3, and SCN1A) were identified previously4, whereas two (FOXP2, MIM 602081, and GRIN2A, MIM 613971) are related genes implicated in other neurodevelopmental phenotypes. We identified all previously observed de novo events (i.e. in the same individuals), as well as additional de novo events in GRIN2B (two protein-truncating events), SCN1A (a missense), and LAMC3 (a missense) (Supplementary Table 8). The observed number of de novo events was compared with expectations based on the mutation rates estimated for each gene (Online Methods and Supplementary Table 8), with GRIN2B showing the highest significance (uncorrected p-value < 0.0002). Notably, the three de novo events observed in GRIN2B are all predicted to be protein-truncating, whereas no events truncating GRIN2B were found in more than 3,000 controls (Online Methods).

Our analysis predicts extreme locus heterogeneity underlying the genetic etiology of autism. Under a strict sporadic disorder-de novo mutation model, if 20–30% of our de novo point mutations are considered “pathogenic”, we can estimate between 384 and 821 loci (Online Methods, Supplementary Fig. 13). We reach a similar estimate if we consider recurrences from Sanders and colleagues9. It is clear from phenotype and genotype data that there are many “autisms” represented under the current umbrella of ASD and other genetic models are more likely in different contexts (for example, families with multiple affected individuals). There is striking convergence on genes previously implicated in intellectual disability and developmental delay. As has been noted for CNVs, this argues that nosological divisions may not readily translate into differences at the molecular level. We believe there is value in comparing mutation patterns in children with developmental delay (without features of autism) to those in ASD.

While there is no one major genetic lesion responsible for ASD, it is still largely unknown whether there are subsets of individuals with a common or strongly related molecular etiology and how large these subsets are likely to be. Using gene expression, protein-protein interactions, and CNV pathway analysis, recent reports have highlighted the role of synapse formation and maintenance26–28. We find it intriguing that 49 proteins found to be mutated here play critical roles in fundamental developmental pathways, including beta-catenin and p53 signaling, and that patients have been identified with multiple disruptive de novo mutations in interconnected pathways. The latter observations are consistent with an oligogenic model of autism where both de novo and extremely rare inherited SNV and CNV mutations contribute in conjunction to the overall genetic risk. Recent work has supported a role for these interconnected pathways in neuronal stem cell fate-determination, differentiation, and synaptic formation in humans and animal models23,29,30. Given that fundamental developmental processes have previously been found to underlie syndromic forms of autism, a wider role of these pathways in idiopathic ASD would not be entirely surprising and would help explain the extreme genetic heterogeneity observed in this study.

Methods Summary

Exome capture, alignments and basecalling

Genomic DNA derived directly from whole blood. Exomes were considered to be completed when ~90% of the capture target exceeded eight-fold coverage and ~80% exceeded 20-fold coverage. Exomes for the 189 trios (and 31 unaffected siblings) were captured with NimbleGen EZ Exome V2.0. Reads were mapped as in 4 to a custom reference genome assembly (GRC build37). Genotypes were generated with GATK unified genotyper and parallel SAMtools pipeline4. Exomes for the unaffected siblings matching the pilot trios were captured and analyzed as in 4. Predicted de novo events were called as in 4 and confirmed by capillary sequencing in all family members (for 176 of the 189 trios this also included one unaffected sibling). Mutations were considered severe if they were truncating, missense with Grantham score >= 50 and GERP score >= 3 or only Grantham score >= 85, or deleted a highly conserved amino acid.

Exome read-depth CNV analysis

Reads were mapped using mrsFAST and normalized RPKM values calculated by exon. Population normalization was performed using a set of 366 non-ASD exomes. Calls were made if three or more exons passed a threshold value and cross-validated calls using two orthogonal platforms, custom array CGH and Illumina 1M array data2. CNVs were filtered to identify de novo and rare inherited events by comparison with 2,090 controls and 1,651 parent profiles.

Network reconstruction and null model estimation

PPI networks were generated using physical interaction data from GeneMANIA21. Null models were estimated using gene-specific mutation rate estimates based on human-chimp divergence. To rank candidate genes we obtain the seed ASD list from17 and severe disruptive de novo events from all families (n = 209). Given the PPI network and seed gene product list, we used DADA22 for ranking each gene.

ONLINE METHODS

Exome Capture, Alignments and Basecalling

Exomes for the 189 trios (and 31 unaffected siblings) were captured with NimbleGen EZ Exome V2.0. Final libraries were then sequenced on either an Illumina GAIIx (paired- or single-end 76 bp reads) or HiSeq2000 (paired- or single-end 50 bp reads). Reads were mapped to a custom GRCh37/hg19 build using BWA 0.5.631. Read qualities were recalibrated using GATK Table Recalibration 1.0.290532. Picard-tools 1.14 was used to flag duplicate reads (http://picard.sourceforge.net/). GATK IndelRealigner 1.0.2905 was used to realign reads around insertion/deletion (indel) sites. Genotypes were generated with GATK Unified Genotyper32 with FILTER = “QUAL <= 50.0 || AB >= 0.75 || HRun > 3 || QD < 5.0” and in parallel with the SAMtools pipeline as described previously4. Only positions with at least eight-fold coverage were considered. All pilot sibling exomes were captured and analyzed as described previously4. Predicted de novo events were called and compared against a set of 946 other exomes to remove recurrent artifacts and likely undercalled sites. Indels were also called with the GATK Unified Genotyper and SAMtools and filtered to those with at least 25% of reads showing a variant at a minimum depth of 8X. Mutations were phased using molecular cloning of PCR fragments, read-pair information, linked informative SNPs, and obligate carrier status. To identify rare private variants (singleton), the full variant list was compared against a larger set of 1,779 other exomes. Predicted de novo indels were also filtered against this larger set.

Sanger Validations

All reported de novo events (exome or MIP capture) were validated by designing primers with BatchPrimer3 followed by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. We performed PCR reactions using 10 ng of DNA from father, mother, unaffected sibling (when available), and proband and performed Sanger capillary sequencing of the PCR product using forward and reverse primers. In some cases, one direction could not be assessed due to the presence of repeat elements or indels in close proximity to the mutation event.

Mutation Candidate Gene Analysis

We examined whether each nonsynonymous or CNV de novo event may be contributing to the etiology of ASD by evaluating the likelihood deleteriousness of the change (GERP, Grantham Score) and intersecting with known syndromic and nonsyndromic candidate genes, CNV morbidity maps, and information in the Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man (OMIM) and PubMed. Mutations were considered severe if they were truncating, missense with Grantham score >= 50 and GERP score >= 3 or only Grantham score >= 85, or deleted a highly conserved amino acid. For genes that had not previously been implicated in ASD, we gave priority to those with structural similarities to known candidate or strong evidence of neural function or development.

Exome Read-depth CNV Discovery

To find CNVs using exome read-depth data, we first mapped sequenced reads to the hg19 exome using the mrsFAST aligner33. Next, we applied a novel method (Krumm et al., in preparation), which uses normalized RPKM values34 of the ~194,000 captured exons/sequences, subsequent population normalization using 366 exomes from the Exome Sequencing Project and singular value decomposition to remove systematic bias present within exome capture reactions. Rare CNVs were detected using a threshold cutoff of the normalized RPKM values, and we required at least three exons above our threshold in order to make a call. We made a total of 1,077 deletion or duplication calls in 366 individuals (range 0–14, median = 3, mean = 2.94).

CNV Detection Using Array CGH

A custom targeted 2×400K Agilent chip with median probe spacing of 500 bp in the genomic hotspots flanked by segmental duplications or Alu repeats and probe spacing of 14 kbp in the genomic backbone was designed. All experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using NA12878 as the female reference and NA18507 as the male reference (Coriell). Data analysis was performed following feature extraction using DNA analytics with ADM-2 setting. All CNVs calls were visually inspected in the UCSC Genome Browser. CNV calls from probands were then intersected with those from parents and also with 377 controls recruited through NIMH Genetics Initiative35,36 and ClinSeq cohort37 analyzed on the same microarray platform. The NIMH set of controls were ascertained by the NIMH Genetics Initiative35 through an online self-report based on the Composite International Diagnostic Instrument Short-Form (CIDI-SF)36. Those who did not meet DSM-IV criteria for major depression, denied a history of bipolar disorder or psychosis, and reported exclusively European origins were included38,39. Samples from the ClinSeq cohort were selected from a population representing a spectrum of atherosclerotic heart disease37. De novo and inherited potential pathogenic CNVs were selected only if they intersected with RefSeq coding sequence and allowing for a frequency of <1% in the controls and <50% segmental duplication content.

Illumina array CNV Calling

CNV calling was performed in hg18 as described previously40, using an HMM that incorporates both allele frequencies (BAF) and total intensity values (logR). In total, we generated CNV calls for 841 probands, 1,651 parents and 793 siblings including the samples reported recently2. Of the 122 families selected for CNV comparisons in this study, calls were generated for 107 probands. Of these, both parents were profiled for 101 families and one parent was profiled for the remaining six families. In addition, at least one sibling was profiled for 99 of these families.

Independent of array CGH detection, to identify putatively pathogenic CNVs, we first compared our data to 2,090 control samples derived from the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium National Blood Services Cohort18,41 and filtered all CNVs present in 1% (20) of WTCCC2 controls or 1% (16) of parents by 50% reciprocal overlap with matching copy number status. In addition, similar to the filtering criteria used for array CGH detection, we selected only CNVs that contained less than 50% segmental duplication and intersected with RefSeq coding sequence. To select putative de novo CNVs, we further required the CNV not to be present in family matched parents and siblings. Additionally, we filtered CNVs present in > 0.1% (2) of the full 1,651 parent set. To select potential, rare inherited events, we required the CNV be detected in a matched parent or sibling. Finally, we filtered the genes inside each CNV under the same criteria (to account for smaller or larger CNPs) and removed CNVs with no remaining genes.

CNV Cross Validation

High confidence, cross validated de novo and inherited CNVs were selected by identifying events detected by at least two of three methodologies. To account for the variable breakpoint definitions in array CGH, SNP arrays, and exome copy number profiles, we aligned the CNVs by at least one overlapping gene ID and reported each CNV region by its maximal outer boundaries. This identified six de novo and 70 rare inherited events for further study (Supplementary Table 5).

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was performed to identify potential functional enrichments within both our PPI (49 genes) and overall set of 126 genes. RefSeq reference gene list was used as a background list for all analysis. To confirm our results pertaining to CTNNB1 upstream enrichment, we simulated 10,000 random populations of 209 individuals using Poisson priors for each gene based on their estimated mutation rates (see below), with a global correction factor resulting in selecting a mean of 126 genes per population. We then used this simulation data to calculate the probability of observing eight direct upstream interactors of CTNNB1 and determined that our data set is enriched for these genes with p = 0.0030.

Estimating Locus-specific Mutation Rates

Human/chimpanzee alignments were downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser (reference versions GRCb37 and panTro2, http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/vsPanTro2/syntenicNet/). The more conservative syntenicNet alignments were used; details in http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/vsPanTro2/README.txt. Gene definitions were downloaded from the UCSC Table Browser, from the RefSeq Genes track, and the refFlat table. Exons were extended by 2 bp, and overlapping exons were merged using BEDTools. Nonexonic sequence was not considered. For each gene, we extracted (1) d = the number of differences between chimpanzee and human and (2) n = the number of bases aligned. We assumed a divergence time between human and chimpanzee of 12 million years and an average generation time of 25 years. We then calculated gene-specific mutation rates per site per generation: r = (d/n)/(12 my/25 years/generation). We calculated the probability of observing X+ events using the Poisson distribution defined by the number of chromosomes screened and the size of the coding region, including actual splice bases.

Network Simulation and Null Model Estimation

To generate a null distribution of gene mutations, de novo mutation rates were estimated from human-chimp mutation rates. A pseudocount of 2.0833E-6 (the smallest calculated in the gene set) was applied to any exon with a mutation rate of zero. To create null gene sets, genes were drawn uniformly from this background distribution. Human protein-protein interaction data was collected from GeneMANIA42 on August 29, 2011. Only direct physical interactions from the Homo sapiens database were considered. The list comprises approximately 1.5 million physical interactions, gathered from 150 studies. A protein interaction network was created from each experimental and null gene set by drawing edges between genes with physical interactions reported in the GeneMANIA database. Qualitatively similar results were achieved by including only interactions supported by multiple independent data sources. For each network, clustering coefficient, centralization, average shortest path length, density, and heterogeneity were determined using Cytoscape43 and Network Analyzer44. Duplicate- and self-interactions were not considered in calculating network statistics.

Disease Gene Prioritization Based on PPI (Protein-Protein Interaction) Networks

We applied degree-aware algorithms to rank a set of candidate genes with respect to a set of products of genes associated with ASD using human protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks. We used the integrated human PPI network data collected from GeneMANIA42 on August 29, 2011. The PPI network contains 12,007 proteins with ~1.5 million direct physical interactions associated with a reliability score. We obtain the seed proteins for the ASD from the list of Betancur17. For the candidate set we used 126 gene products from the severe disruptive de novo events from the pilot autism project4 and the current study. Given the GeneMANIA PPI network and Betancur seed gene product list, we used DADA45 for ranking the candidate genes. We emphasize that this ranking is not implying causality but rather relatedness to genes previously and independently associated with ASD. For testing the significance of this ranking, we rank all the gene products except the seed set using the same algorithm. Based on the ranking result, we applied a Mann-Whiney U rank sum test (one-tailed) on the candidate set compared to all the other genes.

MIP Protocol

Each of 1,703 autism probands from the SSC collection and 744 controls from the NIMH collection was subjected to molecular inversion probe (MIP)-based multiplex capture of the six genes: SCN1A, GRIN2B, GRIN2A, LAMC3, FOXP1, and FOXP2. For each library, 50 ng of DNA was used. Individually synthesized 70 mer MIPs (n = 355) were pooled and 5’ phosphorylated with T4 PNK (NEB). Hybridization with MIPs, gap filling, and ligation were performed in one step for 45–48 h at 60°C, followed by an exonuclease treatment of 30 min at 37°C, similar to 46, with modifications for reduced MIP number (O’Roak et al., in preparation). Amplification of the library was performed by PCR using different barcoded primers for each library. Then barcoded libraries were pooled and purified Agencourt AMPure XP, and one lane of 101 bp paired-end reads was generated for each mega-pool (~384) on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 according to manufacturer’s instructions. Raw reads were mapped to the genome as in 4. MIP targeting arms were then removed and variants called using SAMtools4. A 25-fold coverage, with AB allele ration <0.7, and quality 30 threshold was used for high-confident variant calling. Private (possible de novo) variants were identified by filtering against 1,779 other exomes. The parents of children with disruptive rare variants were then captured. Variants not seen or with low coverage in the parents were validated by Sanger capillary-based fluorescent sequencing. No truncating variants of GRIN2B were observed in the MIP sequenced controls or the Exome Variant Server ESP2500 release (NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/).

Estimating the Number of Autism Loci

The gene-level specificity of exome sequencing enables the estimation of the number of recurrently mutated genes implicated in the genetic etiology of sporadic ASD. This question can be reformulated as the “unseen species problem” (see Bunge and Fitzpatrick 199347 for review; Sanders et al., 20112 for application to de novo CNVs discovered in autism), where genes with severe de novo events in probands are considered “observed species”, and binned by their frequency of appearance (i.e., “singletons”, “doubletons”, etc.). We estimated the total number of genes implicated in autism (the total number of species) using several different estimators (implemented in the R package SPECIES, http://www.jstatsoft.org/), as well as the formula provided in Sanders. This estimate depends on the number of singletons and twin pairs of genes observed in probands, as well as the fraction of de novo events believed to be pathogenic for autism, i.e. single, disruptive events that can cause autism on their own. We assumed that both of our recurrent severe de novo events (affecting CHD8 and NTNG1) were pathogenic; these compose the entire set of twin pairs. The number of singletons is based on the estimated a priori fraction of the observed events that are pathogenic for autism. Across this sliding scale, the estimated number of loci is plotted in Supplementary Fig. 12. For example, using the estimator from Chao and Lee (1992)48, if 20–50% of our de novo severe events are considered pathogenic, exome sequencing of a large number of additional samples would reveal between 182 and 992 pathogenic genes harboring coding de novo point mutations (Supplementary Fig. 12); if all the observed severe de novo events in our experiment are included as pathogenic singletons, the number of implicated loci increases to more than 3,000.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank and recognize the following ongoing studies that produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: NHLBI Lung Cohort Sequencing Project (HL 1029230), NHLBI WHI Sequencing Project (HL 102924), NIEHS SNPs (HHSN273200800010C), NHLBI/NHGRI SeattleSeq (HL 094976), and the Northwest Genomics Center (HL 102926). We are grateful to all of the families at the participating SFARI Simplex Collection (SSC) sites, as well as the principal investigators (A. Beaudet, R. Bernier, J. Constantino, E. Cook, E. Fombonne, D. Geschwind, E. Hanson, D. Grice, A. Klin, R. Kochel, D. Ledbetter, C. Lord, C. Martin, D. Martin, R. Maxim, J. Miles, O. Ousley, K. Pelphrey, B. Peterson, J. Piggot, C. Saulnier, M. State, W. Stone, J. Sutcliffe, C. Walsh, Z. Warren, E. Wijsman). We would also like to acknowledge Matthew State and the Simons Simplex Collection Genetics Consortium for providing Illumina genotyping data, Thomas Lehner and the Autism Sequencing Consortium for providing an opportunity for pre-publication data exchange among the participating groups. We appreciate obtaining access to phenotypic data on SFARI Base. Approved researchers can obtain the SSC population data set described in this study by applying at https://base.sfari.org. Access to the raw sequence reads can be found at the NCBI Short Read Archive and National Database for Autism Research under accession numbers SRA049660 and NDARCOL0001878. This work was supported by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI 137578 & 191889; E.E.E., J.S., and R.B.) and NIH HD065285 (E.E.E. and J.S.). E.B. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow. E.E.E. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Human Subjects

All samples and phenotypic data were collected under the direction of the Simons Simplex Collection by its 12 research clinic sites (http://sfari.org/sfari-initiatives/simons-simplex-collection). Parents consented and children assented as required by each local institutional review board. Participants were de-identified prior to distribution. Research was approved by the University of Washington Human Subject Division under non-identifiable biological specimens/data.

Author contributions

E.E.E., J.S. and B.J.O. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. E.E.E. and J.S. supervised the study. R.B., B.R. and B.J.O. analyzed the clinical information. R.B., L.V., S.G., E.K., N.K., and B.P.C. contributed to the manuscript. S.G., N.K., B.P.C., A.K., C.B., M.M., and L.V. generated and analyzed CNV data. B.J.O. and L.V. performed MIP resequencing and mutation validations. I.B.S., E.H.T., B.J.O., and J.S. developed MIP protocol and analysis. B.V. and J.M.A. generated loci specific mutation rate estimates. R.L. and E.B. performed PPI network analysis and simulations. E.K. performed DADA analysis. C.L. performed Illumina sequencing and analysis. B.P.C. performed IPA analysis. B.J.O., E.K., and N.K. developed the de novo analysis pipelines and analyzed sequence data. D.A.N., M.J.R., J.D.S., and E.H.T. supervised exome sequencing and primary analysis.

References

- 1.Schaaf CP, Zoghbi HY. Solving the autism puzzle a few pieces at a time. Neuron. 2011;70:806–808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders SJ, et al. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:863–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, et al. Rare de novo and transmitted copy-number variation in autistic spectrum disorders. Neuron. 2011;70:886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Roak BJ, et al. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:585–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hultman CM, Sandin S, Levine SZ, Lichtenstein P, Reichenberg A. Advancing paternal age and risk of autism: new evidence from a population-based study and a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Molecular psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischbach GD, Lord C. The Simons Simplex Collection: a resource for identification of autism genetic risk factors. Neuron. 2010;68:192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.006. S0896-6273(10)00830-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch M. Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:961–968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912629107. 0912629107 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu B, et al. Exome sequencing supports a de novo mutational paradigm for schizophrenia. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:864–868. doi: 10.1038/ng.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders SJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hehir-Kwa JY, et al. De novo copy number variants associated with intellectual disability have a paternal origin and age bias. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2011;48:776–778. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Roak BJ, State MW. Autism genetics: strategies, challenges, and opportunities. Autism Res. 2008;1:4–17. doi: 10.1002/aur.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimura-Akiyoshi S, Niimi K, Nakashiba T, Itohara S. Axonal netrin-Gs transneuronally determine lamina-specific subdendritic segments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14801–14806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borg I, et al. Disruption of Netrin G1 by a balanced chromosome translocation in a girl with Rett syndrome. European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2005;13:921–927. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiyama M, et al. CHD8 suppresses p53-mediated apoptosis through histone H1 recruitment during early embryogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:172–182. doi: 10.1038/ncb1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson BA, Tremblay V, Lin G, Bochar DA. CHD8 is an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factor that regulates beta-catenin target genes. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:3894–3904. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00322-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batsukh T, et al. CHD8 interacts with CHD7, a protein which is mutated in CHARGE syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19:2858–2866. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betancur C. Etiological heterogeneity in autism spectrum disorders: more than 100 genetic and genomic disorders and still counting. Brain research. 2011;1380:42–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper GM, et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:838–846. doi: 10.1038/ng.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buysse K, et al. Delineation of a critical region on chromosome 18 for the del(18)(q12.2q21.1) syndrome. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2008;146A:1330–1334. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoischen A, et al. De novo mutations of SETBP1 cause Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2010;42:483–485. doi: 10.1038/ng.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warde-Farley D, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:W214–220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erten S, Bebek G, Ewing R, Koyutürk M. DADA: Degree-Aware Algorithms for Network-Based Disease Gene Prioritization. BioData Mining. 2011;4:1–20. doi: 10.1186/1756-0381-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Ferrari GV, Moon RT. The ups and downs of Wnt signaling in prevalent neurological disorders. Oncogene. 2006;25:7545–7553. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedogni F, et al. Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:13129–13134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002285107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner EH, Lee C, Ng SB, Nickerson DA, Shendure J. Massively parallel exon capture and library-free resequencing across 16 genomes. Nature methods. 2009;6:315–316. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voineagu I, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. 2011;474:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakai Y, et al. Protein interactome reveals converging molecular pathways among autism disorders. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:86ra49. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilman SR, et al. Rare de novo variants associated with autism implicate a large functional network of genes involved in formation and function of synapses. Neuron. 2011;70:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ille F, Sommer L. Wnt signaling: multiple functions in neural development. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2005;62:1100–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4552-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tedeschi A, Di Giovanni S. The non-apoptotic role of p53 in neuronal biology: enlightening the dark side of the moon. EMBO reports. 2009;10:576–583. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. btp324 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:491. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hach F, et al. mrsFAST: a cache-oblivious algorithm for short-read mapping. Nat Methods. 2010;7:576–577. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-576. nmeth0810-576 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moldin SO. NIMH Human Genetics Initiative: 2003 update. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:621–622. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biesecker LG, et al. The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome research. 2009;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talati A, Fyer AJ, Weissman MM. A comparison between screened NIMH and clinically interviewed control samples on neuroticism and extraversion. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:122–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002114. 4002114 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baum AE, et al. A genome-wide association study implicates diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH) and several other genes in the etiology of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:197–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002012. 4002012 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itsara A, et al. Population analysis of large copy number variants and hotspots of human genetic disease. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2009;84:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craddock N, et al. Genome-wide association study of CNVs in 16,000 cases of eight common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2010;464:713–720. doi: 10.1038/nature08979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mostafavi S, Ray D, Warde-Farley D, Grouios C, Morris Q. GeneMANIA: a real-time multiple association network integration algorithm for predicting gene function. Genome biology. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s1-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Assenov Y, Ramirez F, Schelhorn SE, Lengauer T, Albrecht M. Computing topological parameters of biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:282–284. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erten S, Bebek G, Koyutürk M. Disease Gene Prioritization Based on Topological Similarity in Protein-Protein Interaction Networks. 2011;6577 doi: 10.1089/cmb.2011.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mamanova L, et al. Target-enrichment strategies for next-generation sequencing. Nature methods. 2010;7:111–118. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bunge J, Fitzpatrick M. Estimating the Number of Species - a Review. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88:364–373. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chao A, Lee SM. Estimating the Number of Classes Via Sample Coverage. J Am Stat Assoc. 1992;87:210–217. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.