Abstract

Phenotypic and genetic variation in bacteria can take bewilderingly complex forms even within a single genus. One of the most intriguing examples of this is the genus Neisseria, which comprises both pathogens and commensals colonizing a variety of body sites and host species, and causing a range of disease. Complex relatedness among both named species and previously identified lineages of Neisseria makes it challenging to study their evolution. Using the largest publicly available collection of bacterial sequence data in combination with a population genetic analysis and experiment, we probe the contribution of inter-species recombination to neisserial population structure, and specifically whether it is more common in some strains than others. We identify hybrid groups of strains containing sequences typical of more than one species. These groups of strains, typical of a fuzzy species, appear to have experienced elevated rates of inter-species recombination estimated by population genetic analysis and further supported by transformation experiments. In particular, strains of the pathogen Neisseria meningitidis in the fuzzy species boundary appear to follow a different lifestyle, which may have considerable biological implications concerning distribution of novel resistance elements and meningococcal vaccine development. Despite the strong evidence for negligible geographical barriers to gene flow within the population, exchange of genetic material still shows directionality among named species in a non-uniform manner.

Keywords: fuzzy species, recombination, Neisseria

1. Introduction

The genus Neisseria consists of Gram-negative bacteria that colonize the mucous membranes of mammals. Two species, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis (the meningococcus), are important pathogens in humans, while other neisserial species have rarely been associated with symptomatic illness. Neisseria lactamica is the neisserial species that most commonly colonizes the nasopharynx of infants and young children [1,2], and in this population, meningococcal carriage is low, rising to high levels only in adolescence and young adult life [3].

Another feature of the Neisseria is their high rate of homologous recombination [4,5]. This has been known for some time, and has the important clinical consequence that it can spread genes encoding antibiotic resistance among lineages and even species [6]. It is also a crucial contributor to the rapid diversification of surface antigens, allowing immune evasion [7,8]. The result of this high rate of recombination is that within species phylogenies constructed from unlinked housekeeping loci are no more similar than random, recombination having scrambled phylogenetic signal at all but the most closely related strains [9]. Homologous recombination occurs more efficiently between closely related donor and recipient sequences, but it can and does also occur between more distantly related taxa, including species boundaries. Owing to the co-colonization of meningococcus and N. lactamica at the same body site, opportunities occur frequently in nature for the occasional transfer of DNA between them. Interspecific recombination means that it is not uncommon to find a strain securely identified as one species, but which contains a locus or loci with sequence typical of another species [10]. The impact of this admixture on species formation and identification has attracted considerable interest in recent years, and it has been proposed that it might explain historical difficulties with the taxonomy of the Neisseria (among others). The term ‘fuzzy species’ was coined to describe a situation in which, due to inter-species recombination, the fringes of a given named species cluster in a notional sequence space are not discrete and contain mosaics of genetic material from more than one named species [10].

Such mosaics were identified in Neisseria using data collected for multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [11], which types pathogens using the DNA sequence at multiple unlinked housekeeping loci. The scheme developed for the meningococcus can also be used for related species, and trees built from concatenates of these clearly showed the existence of meningococci and N. lactamica strains containing multiple loci characteristic of more than one named species [10].

The observation of relatively pervasive recombination between named species creates insecurity in current species concepts [12–14]. One response to this uncertainty is to focus on loci at which recombination is less frequently found, either because it is more rare or more difficult to detect. An approach using highly conserved ribosomal proteins, retrieved from multiple genomes of Neisseria and streptococci, has been developed [15]. While such strategies are likely to be of great value in the question of how to pragmatically use sequence data to define species, any limited set of loci can, by definition, tell us nothing about variation and recombination elsewhere in the genome.

Serogroup A meningococci are thought to undergo recombination at a lower rate than other members of the same species [16]. Such variation in recombination rate is a matter of interest because, as noted earlier, higher recombination rates are thought to be associated with a greater risk that the strains concerned acquire resistance or virulence determinants. Circumstantial evidence for such a link already exists for Streptococcus pneumoniae [17]. The extent to which meningococci vary in their recombination rate is poorly understood, but as noted may have important consequences for evolution. Strains that contain mosaics of sequence data typical of more than one species might be inferred to have a higher recombination rate, or to have performed so at some point in the past. The biological significance of these mosaic genotypes is not clear, and could be an epiphenomenon: in other words, the limited sample of genes studied is not predictive of the phenotype of the organism, and that these strains are simply rare examples of meningococci (or N. lactamica strains) that have undergone recombination at one of the loci used for MLST, and that this is of negligible importance for the study of the strain, the species, or the evolution of either. Even if there is no variation among strains in the rate of recombination, some will be expected to have more recombinant loci simply by chance. However, commensal neisserial strains have been suggested as live attenuated vehicles for vaccine strategies [18], and hence the degree and frequency of recombination between N. lactamica and the meningococcus is a matter of more than theoretical concern.

To fully assess the importance of mosaic strains requires both an experimental and computational approach. Although as noted earlier, in the meningococcus, the phylogeny of one locus is no better than chance at predicting that of another unlinked locus, clusters of related strains, and the degree of admixture (recombination) between them can be identified by a number of statistical approaches [19–21]. If any such clusters can be securely identified that show a greater frequency of admixture between species, they then can be examined to find whether this is associated with any other features, including difficulty in species definition. Furthermore, any such strains can be directly tested in the laboratory to estimate whether they are more permissive of transformation under experimental conditions.

In this paper, we use a combination of sequence data, statistical analysis and experiment to probe the contribution of recombination to neisserial population structure, and specifically apparent hybrid groups of strains containing sequence data typical of more than one species.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sources of sequence data

Among all human and animal pathogens and commensals that have been studied using a MLST scheme [11], the amount of publicly available data is most extensive for Neisseria. We used a complete set of the available sequence types (STs) for Neisseria from http://pubmlst.org/neisseria/ as of the 26 November 2010. The database contained 8619 STs with sequences available for the following seven genes: abcZ, adk, aroE, fumC, gdh, pdhC and pgm. The database also contains information on which species each strain was assigned to in the laboratory submitting the sequence data. The input dataset comprised 8074 strains identified as meningococcus, 283 as N. lactamica, 193 as N. gonorrhoeae, four as N. cinerea, three as N. flava, two as N. flavescens, four as N. mucosa, four as N. mucosa, four as N. perflava, seven as N. polysaccharea, six as N. sicca and four as N. subflava. In addition, 31 strains had unresolved species status.

The strains used in the transformation experiments were obtained through the generosity of Prof. M. Maiden, University of Oxford, UK, Dr Heike Claus, Universität Würzburg, Germany and our own collection. Neisserial strains were routinely propagated at 37°C with 5 per cent CO2 on GC agar (Difco) supplemented with 1 per cent Vitox (Oxoid) or at 37°C, 180 r.p.m. in Mueller–Hinton broth (Oxoid) with 1 per cent Vitox.

Nalidixic acid-resistant derivatives of N. lactamica were selected by exposure of strains grown to the stationary phase in broth cultures to nalidixic acid at 10 µg ml−1, followed by overnight growth on selection medium to isolate spontaneous gyrase mutants. The N. lactamica strains used were ST 595 and ST 3493.

2.2. Transformation experiments

Neisserial strains (1 × 108 cfu ml−1) were incubated with 1 µg ml−1 chromosomal DNA isolated from a gyrase mutant in Mueller–Hinton broth supplemented with 1 per cent Vitox. Following 4 h incubation at 37°C 5 per cent CO2, the transformation mix was plated onto GC agar plates supplemented with 1 per cent Vitox containing 20 µg ml−1 nalidixic acid. Transformation frequencies were determined as the number of antibiotic resistant colony-forming unit per millilitre recovered divided by the total colony-forming unit per millilitre counted on non-selective medium. For each meningococcal isolate, transformation frequencies were measured in triplicate against both derivatives of N. lactamica strains. Details of the meningococcal strains used in the experiments are given in the electronic supplementary material, table S1.

2.3. Sequence analysis

We used BAPS software [21,22] to cluster the sequences into genetically distinct groups and to infer the amount of gene flow between the groups. The optimal clustering was obtained using 10 runs of the estimation algorithm with the prior upper bound of the number of clusters varying in the range (100, 300) over the 10 replicates. All estimation runs yielded highly congruent partitions of the ST data with either 50 or 51 clusters, indicating a strongly peaked posterior distribution in the neighbourhood of these partitions. The estimated posterior mode clustering had 50 clusters, and the admixture analysis was subsequently performed using these clusters with 100 Monte Carlo replicates for allele frequencies and by generating 100 reference genotypes to calculate p-values. For reference cases, we used 10 iterations in estimation according to the guidelines of Corander & Marttinen [23]. An ST was considered significantly admixed if the p-value did not fall below the threshold of 5 per cent. Given the extremely large number of STs in the data, the population genetic analyses took approximately 5360 computational hours. For further details about the methods implemented in BAPS, see the original papers.

2.4. Phylogenetics

To examine the relatedness of hybrid clusters to each other and the entire sample, we constructed a maximum-likelihood tree using concatenates of MLST sequences for all STs in our dataset. The tree was produced using RAxML v. 7.0.4 [24], with a general time reversible model and gamma model of rate heterogeneity. We used the rapid hillclimbing mode (option –f), and the bootstrapping was calculated by drawing the bipartition information onto the tree, based on the results from 100 individual bootstrap replicates. The 100 bootstrap replicates were computed on a parallel environment and the whole analysis was repeated twice due to numerical problems in the first run, such that only results from the second run are included in the study. The RAxML analyses took in total approximately 14 544 computational hours. It must be noted that the details of these phylogenies are highly suspect owing to the impact of recombination, and hence taxon labels have been removed. We wish to further emphasize the fact that the trees reported are primarily intended for examining the molecular distances among the BAPS groups and to see which groups form well-resolved clusters of STs in the tree.

3. Results

3.1. Results of BAPS analysis and identification of significantly mixed groups

BAPS clustered the MLST data into 50 groups, of which 42 contained strains of a single species (N. meningitidis), whereas the remaining eight groups contained isolates of at least two species, in which case we label them as mixed (table 1). The observed species distribution of mixed N. lactamica and N. meningitidis groups (2, 31, 41, 46) was highly significant in comparison with the null hypothesis that all strains are equally likely to be erroneously identified at the species level, indicating that these clusters are indeed taxonomically problematic (for details of these tests, and for complete results of population genetic analyses, see the electronic supplementary material). In the following, we focus primarily on the earlier-mentioned groups containing strains significantly identified as more than one species, to address their relationship to admixture and mosaicism between meningococcus and N. lactamica.

Table 1.

Frequencies of STs from different Neisseria species among mixed BAPS groups. Percentage of each species within a group is given within parentheses.

| species/group | 2 | 31 | 34 | 41 | 46 | 48 | 49 | 50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neisseria cinerea | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (6.3%) | ||||||

| Neisseria flava | 3 (14.3%) | |||||||

| Neisseria flavescens | 2 (9.5%) | |||||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 193 (99.5%) | |||||||

| Neisseria lactamica | 48 (88.9%) | 225 (84.0%) | 4 (16.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | 1 (2.1%) | |||

| Neisseria meningitidis | 6 (11.1%) | 43 (16.0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 20 (83.3%) | 23 (82.1%) | 6 (12.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Neisseria mucosa | 1 (4.8%) | 3 (37.5%) | ||||||

| Neisseria perflava | 4 (19.0%) | |||||||

| Neisseria polysaccharea | 7 (14.6%) | |||||||

| Neisseria sicca | 3 (14.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | ||||||

| Neisseria subflava | 3 (14.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | ||||||

| unknown | 3 (14.3%) | 31 (64.6%) |

The population genetic analysis identified four mixed groups of N. lactamica and N. meningitidis STs containing in total 282 N. lactamica and 92 N. meningitidis STs (table 1). In addition, there are three other mixed groups (34, 48, 49) with higher level of species heterogeneity and a single group (50) into which all N. gonorrhoeae STs were assigned. Frequencies of different serotypes of N. meningitidis within the four mixed BAPS groups (2, 31, 41, 46) and in total among N. meningitidis are shown in table 2. Additional data on serotypes and epidemiological variables (electronic supplementary material) further corroborate the strong link between N. lactamica and N. meningitidis in the mixed groups at the phenotypic level. The serotypes of N. meningitidis STs in groups 2, 31 and 41 are almost exclusively non-groupable (94%), and isolates of the STs in these groups are almost always retrieved from carriage (99.4%). The only known serotypes observed in these mixed groups are B and A, and both these at very low frequencies (4.4% and 1.6%, respectively). In comparison, among all N. meningitidis the frequency of non-typeables is 18 per cent and serotype B 47 per cent. The last mixed group (46) is slightly more heterogeneous in terms of both its molecular and phenotypic characteristics in relation to the other three mixed groups. For that group, 63 per cent of the STs are found from carriers, 25.9 per cent from invasive disease and 11.1 per cent from meningitis cases. Similarly, the serotype distribution in group 46 is less concentrated on the non-groupables (36.4%), such that five known serotypes are observed with joint frequency of 63.6 per cent, where B is the most frequent (27.3%).

Table 2.

Frequencies of different serotypes of Neisseria meningitidis within four particular mixed BAPS groups and in total among N. meningitidis. Percentage of each serotype is given within parentheses.

| serotype/group | 2 | 31 | 41 | 46 | all groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29E | 1 (4.5%) | 106 (1.4%) | |||

| A | 1 (5.6%) | 147 (1.9%) | |||

| B | 3 (7%) | 6 (27.3%) | 4043 (54.4%) | ||

| C | 3 (13.6%) | 732 (9.8%) | |||

| H | 4 (<0.01%) | ||||

| K | 2 (<0.01%) | ||||

| NG | 6 (100%) | 40 (93%) | 17 (94.4%) | 8 (36.4%) | 1574 (21.2%) |

| other | 9 (<0.01%) | ||||

| W-135 | 266 (3.6%) | ||||

| X | 1 (4.5%) | 117 (1.6%) | |||

| Y | 3 (13.6%) | 371 (5.0%) | |||

| Z | 50 (<0.01%) |

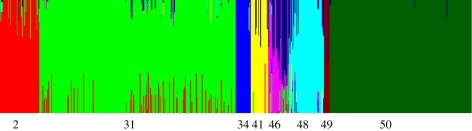

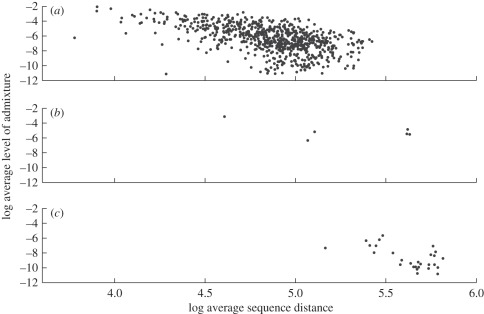

3.2. Admixture analysis: identification of hybrid groups

To examine whether BAPS groups vary in the degree to which recombination has contributed to their composition, we used BAPS admixture analysis [21]. Given the large number of detected groups, it is not feasible to visualize them simultaneously with respect to the estimated level of admixture. Figure 1 shows the admixture estimates for the STs in the mixed groups such that the level of gene flow from purely N. meningitidis groups is also visible. The admixture results jointly for all groups are numerically presented in a table format in the electronic supplementary material. We here define a hybrid group as one that contains a greater proportion of variation characteristic of more than one cluster, than expected by chance (given the observed amount of admixture in the entire dataset). Since the recombination frequency is expected to be dependent on sequence similarity, it is necessary to take this into account when quantitatively comparing different groups. Figure 2 shows the distribution of levels of significant non-zero admixture between the following three sets of BAPS groups: (i) purely N. meningitidis, (ii) mixed N. lactamica and N. meningitidis and (iii) between sets in (i) and (ii). The fraction of pairs of groups with an inferred average level of admixture equal to zero is 12.8 per cent, 0 per cent and 83 per cent for these three cases, respectively. The decreasing amount of admixture as a function of molecular distance is well visible in figure 2. However, the mixed N. lactamica and N. meningitidis groups show evidence of considerably higher level admixture at molecular distances equivalent to those found between the two species groups in general. Thus, those groups with evidence of taxonomic uncertainty are considerably more hybrid than non-mixed ones.

Figure 1.

BAPS estimates of admixture for the STs in the mixed groups. Each ST corresponds to a coloured vertical bar, where fractions of colours indicate the amount of variation attributed to a particular group. For STs with non-significant admixture (p-value greater than 5%), the bars are single-coloured. The dark blue colour refers to the sum of estimated admixture from any of the 42 groups harbouring solely Neisseria meningitidis STs.

Figure 2.

Estimated average levels of admixture (a) between Neisseria meningitidis groups, (b) between mixed N. meningitidis and N. lactamica groups, (c) between N. meningitidis groups and the mixed groups. On the vertical axis, the values are natural logarithms of the mean level of admixture between STs in a particular pair of groups. On the horizontal axis, the values are natural logarithms of the mean sequence distance between STs in a particular pair of groups.

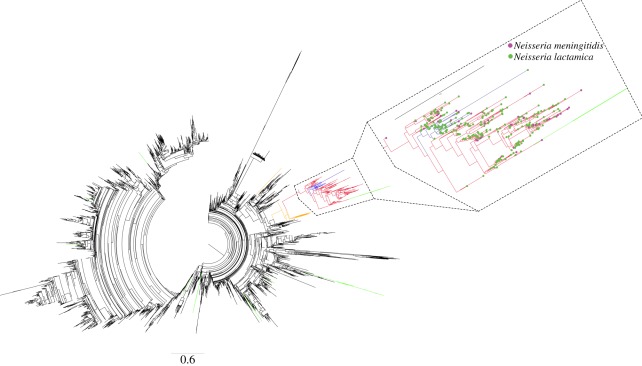

3.3. Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic tree in figure 3 shows the position of STs in groups 2, 31, 41 and 46 in the overall database. It should be noted that the details of this tree must be considered suspect owing to recombination, and we make no particular claims regarding ordering of the branches. Groups 2, 31 and 41 are shown as closely related to each other, forming well-resolved clusters. In contrast, group 46 is not coherent, and its component STs are scattered around the tree.

Figure 3.

Maximum-likelihood tree for the 8619 STs with BAPS groups 2 (blue lines), 31 (red lines), 41 (orange lines), 46 (green lines) marked by coloured branches. In addition, the subtree corresponding to groups 2 and 31 is magnified.

Laboratory errors containing randomly selected alleles from the meningococcal and N. lactamica populations would not be expected to cluster together in a phylogeny. Hence, the clustering of STs in groups 2, 31 and 41 strongly argues against the interpretation that these hybrid groups are laboratory artefacts, while group 46 may be. Finally, STs arising from laboratory errors should not be found more than once, and 46 STs in the hybrid groups have been recorded on more than one occasion, providing further evidence that these observations are secure.

3.4. Results of transformation experiments

The earlier-mentioned accounts suggest that strains in the mixed N. lactamica and N. meningitidis groups may be more likely to take up DNA than others. We therefore directly examined the degree of variation in transformation rates among strains from the mixed and non-mixed groups. The data are shown in the electronic supplementary material, figure S5. A linear-correlated random effects model was fitted to the data using SPSS 17 to account for the dependences within each triplicate measurement corresponding to the same combination of a meningococcal and N. lactamica strain. Grouping with respect to mixed and non-mixed STs was used as a fixed effect in the model, and the difference between the two groups was significant at 5 per cent level (p-value 0.048). A single meningococcal isolate in the mixed group failed to produce any measurable transformation frequency against both N. lactamica strains. Similarly, zero frequencies were also observed for all replicates of a single isolate in the non-mixed group. When these zero frequencies are excluded from the random effects analysis, the p-value for the difference equals 0.013.

4. Discussion

It has been previously reported that the Neisseria undergo recombination within and between species, to the extent that it confounds conventional phylogenetic analyses [9]. This has led to the ‘fuzzy species’ concept, first applied to the Neisseria, which states that recombination between named species produces strains that contain a mosaic of DNA sequence characteristic of each, and which blurs the genotypic boundaries between species [10]. While the fuzzy species concept accurately reflects the observed distribution of genotypes in sequence space, the biological significance of the mosaic strains has remained uncertain. Are these strains phonetically as well as genetically plastic [12], and are they only transient, with little evolutionary future, because as previously stated ‘the fate of hybrid genotypes is important’ [25]? We have found groups of strains with evidence of significant past admixture between the named species N. meningitidis and N. lactamica, and moreover that these are also characterized by clear evidence of taxonomic confusion.

The identification of bacteria to the species level in clinical laboratories is an important part of patient care, determining appropriate therapies and treatment regimens. Despite this, occasional errors do occur. However, the ability of N. lactamica to produce beta-galactosidase and acid from lactose is normally considered to distinguish it well from the meningococcus [26]. We have shown in this work that some groups of related N. lactamica and meningococcus strains are more difficult to securely identify than this would suggest, given the mixture of species identifications within them. It is not possible to determine from the database whether the distribution of phenotypic characteristics in these groups is divergent from that found among strains in the main meningococcal and lactamica clusters. However, if we take species identification as a proxy for phenotype, then we can conclude that this is likely the case. Strikingly, we also find that these mixed groups contain sequence data found to be characteristic of both the meningococcus and N. lactamica, providing an association (though not a causal link) between a history of recombination and phenotypic variation. Such phenotypic variation arising from genetic plasticity may be a contributing factor to difficulties with species classification. The relatively close relationships between the STs in these groups, as displayed by the tree shown in figure 3, argue that they are not laboratory artefacts produced by mixed cultures. Further evidence for this assertion comes from the preponderance of strains among those isolates identified as meningococcus for which no serogroup can be determined: greater than 90 per cent of isolates in groups 2, 31 and 41, in contrast with only 21 per cent of isolates in all meningococci (table 2). The observed accumulation of non-groupable strains is clearly significant (p-value less than 0.001) in these three groups (for details of tests, see the electronic supplementary material). The exception is group 46, which is scattered around the tree (figure 3) and contains a smaller proportion of non-groupable strains (p-value 0.075). Group 46, containing 28 STs, may indeed be composed of laboratory errors, but we are confident that this explanation can be rejected for groups 2, 31 and 41, which together contain 346 STs.

We have also examined differences in transformation rate between strains directly by experiment. While relatively few transformation experiments were performed, we nevertheless found a significant difference, among transformable strains, between the mean transformation efficiencies of members of mixed BAPS groups and those that were not. While this observation would in isolation be difficult to interpret, together with the results of the computational analyses presented here, it provides further support for the existence of marked variation in recombination rate among Neisseria lineages.

The reasons for the variation in interspecific recombination that we observe among BAPS groups are obscure. Both mechanistic and ecological factors are plausible contributors. Neisseria lactamica is known to typically colonize younger children than N. meningitidis [2]. A sub-population of N. lactamica that preferentially colonized older hosts would be expected to encounter meningococci more frequently, just as similar opportunities for interspecific recombination would be offered by a meningococcal sub-population preferentially colonizing younger children. Other plausible factors include features of the mismatch repair system [27], or restriction modification systems [28,29]. Since the lineages with extended interspecific recombination have survived long enough to produce a cluster of related strains, any selective impact cannot be too deleterious. On the other hand, these lineages are also rare, which possibly suggests either some selective cost or that they have arisen only very recently. One possible scenario is that these strains have derived a short-term selective advantage by lowering the barriers to the incorporation of DNA from the other species, and as a result have acquired loci from that other species that allow them to colonize a new region of niche space. However, this must remain speculation in the absence of more whole genome data, and an improved understanding of the relevant ecological niche structure.

It is evident that extensive recombination has shaped the evolution of Neisseria. However, even if the gene flow within the population appears to have very, if indeed any, limited geographical barriers, it still exhibits directionality among named species in a non-uniform manner. Exchange of particular genes (aroE, glnA) between N. lactamica and N. meningitidis strains has been reported previously [30]. However, the large-scale population study conducted here reveals separate evolutionary lineages within the N. meningitidis population, such that the level of recombination between them is smaller than within the lineages, even when controlling for the molecular distance. There is also a clear and consistent directionality in recombination between gonococci and other named species. Consistent with previous observations, the gonococci in the database contain no sequence characteristic of other clusters [10,31]. However, there is clear evidence of transfer from gonococcus to mixed groups, established by examining sequence variation in individual loci (electronic supplementary material).

5. Conclusion

Bacteria can fall into a bewilderingly complicated range of population structures. The principles underlying each however can be abstractly understood in terms of the generation and shuffling of molecular variation. We have shown here the synergy between genetics, statistics and laboratory experiments in helping to elucidate some features of neisserial population structure. The methods we discuss and apply may be complemented by others both already available and in development, and the increasing numbers of whole genomes will enormously aid in this enterprise.

Acknowledgements

This publication made use of the Neisseria multi-locus sequence typing website (http://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) developed by Keith Jolley and sited at the University of Oxford. The development of this site has been funded by the Wellcome Trust and European Union. C.A.O'D. and J.S.K. were supported by generous grants to J.S.K. from Caroline Conran, from the Livanos Trust and funding from the Health Protection Agency, UK. We wish to thank Martin Maiden for providing the N. lactamica strains. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which led to considerable improvements in the article. This work benefited significantly from discussions with participants of the 2nd Permafrost Workshop. The work of J.C. was supported by ERC grant no. 239784 and a grant from Sigrid Juselius Foundation. W.P.H. was supported by award number U54GMO88558 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Blakebrough I. S., Greenwood B. M., Whittle H. C., Bradley A. K., Gilles H. M. 1982. The epidemiology of infections due to Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria lactamica in a northern Nigerian community. J. Infect. Dis. 146, 626–637 10.1093/infdis/146.5.626 (doi:10.1093/infdis/146.5.626) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold R., Goldschneider I., Lepow M. L., Draper T. F., Randolph M. 1978. Carriage of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria lactamica in infants and children. J. Infect. Dis. 137, 112–121 10.1093/infdis/137.2.112 (doi:10.1093/infdis/137.2.112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen S. F., Djurhuus B., Rasmussen K., Joensen H. D., Larsen S. O., Zoffman H., Lind I. 1991. Pharyngeal carriage of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria lactamica in households with infants within areas with high and low incidences of meningococcal disease. Epidemiol. Infect. 106, 445–457 10.1017/S0950268800067492 (doi:10.1017/S0950268800067492) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feil E. J., Maiden M. C., Achtman M., Spratt B. G. 1999. The relative contributions of recombination and mutation to the divergence of clones of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1496–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith N. H., Holmes E. C., Donovan G. M., Carpenter G. A., Spratt B. G. 1999. Networks and groups within the genus Neisseria: analysis of argF, recA, rho, and 16S rRNA sequences from human Neisseria species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 773–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spratt B. G., Zhang Q. Y., Jones D. M., Hutchison A., Brannigan J. A., Dowson C. G. 1989. Recruitment of a penicillin-binding protein gene from Neisseria flavescens during the emergence of penicillin resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 8988–8992 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8988 (doi:10.1073/pnas.86.22.8988) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews T. D., Gojobori T. 2004. Strong positive selection and recombination drive the antigenic variation of the PilE protein of the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis. Genetics 166, 25–32 10.1534/genetics.166.1.25 (doi:10.1534/genetics.166.1.25) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urwin R., Holmes E. C., Fox A. J., Derrick J. P., Maiden M. C. 2002. Phylogenetic evidence for frequent positive selection and recombination in the meningococcal surface antigen PorB. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 1686–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feil E. J., et al. 2001. Recombination within natural populations of pathogenic bacteria: short-term empirical estimates and long-term phylogenetic consequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 182–187 10.1073/pnas.98.1.182 (doi:10.1073/pnas.98.1.182) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanage W. P., Fraser C., Spratt B. G. 2005. Fuzzy species among recombinogenic bacteria. BMC Biol. 3, 6. 10.1186/1741-7007-3-6 (doi:10.1186/1741-7007-3-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiden M. C., et al. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3140–3145 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140 (doi:10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doolittle W. F., Zhaxybayeva O. 2009. On the origin of prokaryotic species. Genome Res. 19, 744–756 10.1101/gr.086645.108 (doi:10.1101/gr.086645.108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser C., Hanage W. P., Spratt B. G. 2007. Recombination and the nature of bacterial speciation. Science 315, 476–480 10.1126/science.1127573 (doi:10.1126/science.1127573) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevers D., et al. 2005. Opinion: re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 733–739 10.1038/nrmicro1236 (doi:10.1038/nrmicro1236) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolley K. A., Maiden M. C. 2010. BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 595. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-595) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bart A., Barnabe C., Achtman M., Dankert J., van der Ende A., Tibayrenc M. 2001. The population structure of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A fits the predictions for clonality. Infect. Genet. Evol. 1, 117–122 10.1016/S1567-1348(01)00011-9 (doi:10.1016/S1567-1348(01)00011-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanage W. P., Fraser C., Tang J., Connor T. R., Corander J. 2009. Hyper-recombination, diversity, and antibiotic resistance in pneumococcus. Science 324, 1454–1457 10.1126/science.1171908 (doi:10.1126/science.1171908) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Dwyer C. A., Reddin K., Martin D., Taylor S. C., Gorringe A. R., Hudson M. J., Brodeur B. R., Langford P. R., Kroll J. S. 2004. Expression of heterologous antigens in commensal Neisseria spp.: preservation of conformational epitopes with vaccine potential. Infect. Immun. 72, 6511–6518 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6511-6518.2004 (doi:10.1128/IAI.72.11.6511-6518.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corander J., Waldmann P., Marttinen P., Sillanpaa M. J. 2004. BAPS 2: enhanced possibilities for the analysis of genetic population structure. Bioinformatics 20, 2363–2369 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth250 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth250) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corander J., Waldmann P., Sillanpaa M. J. 2003. Bayesian analysis of genetic differentiation between populations. Genetics 163, 367–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang J., Hanage W. P., Fraser C., Corander J. 2009. Identifying currents in the gene pool for bacterial populations using an integrative approach. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000455. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000455 (doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000455) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corander J., Marttinen P., Siren J., Tang J. 2008. Enhanced Bayesian modelling in BAPS software for learning genetic structures of populations. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 539. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-539 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-539) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corander J., Marttinen P. 2006. Bayesian identification of admixture events using multilocus molecular markers. Mol. Ecol. 15, 2833–2843 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02994.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02994.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maiden M. C. 2008. Population genomics: diversity and virulence in the Neisseria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 467–471 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.002 (doi:10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knapp J. S., Rice R. J. 1995. Neisseria and Branhamella. In Manual of clinical microbiology (eds Murray P. R., Baron E. J., Pfaller M. A., Tenover F. C., Yolken R. H.), pp. 324–340, 6th edn Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander H. L., Richardson A. R., Stojiljkovic I. 2004. Natural transformation and phase variation modulation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 771–783 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04013.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04013.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budroni S., et al. 2011. Neisseria meningitidis is structured in clades associated with restriction modification systems that modulate homologous recombination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4494–4499 10.1073/pnas.1019751108 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1019751108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claus H., Friedrich A., Frosch M., Vogel U. 2000. Differential distribution of novel restriction-modification systems in clonal lineages of Neisseria meningitidis. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1296–1303 10.1128/JB.182.5.1296-1303.2000 (doi:10.1128/JB.182.5.1296-1303.2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J., Bowler L. D., Spratt B. G. 1997. Interspecies recombination, and phylogenetic distortions, within the glutamine synthetase and shikimate dehydrogenase genes of Neisseria meningitidis and commensal Neisseria species. Mol. Microbiol. 23, 799–812 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2681633.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2681633.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett J. S., Jolley K. A., Sparling P. F., Saunders N. J., Hart C. A., Feavers I. M., Maiden M. C. 2007. Species status of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evolutionary and epidemiological inferences from multilocus sequence typing. BMC Biol. 5, 35. 10.1186/1741-7007-5-35 (doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-35) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]