Abstract

Human disease animal models are absolutely invaluable tools for our understanding of mechanisms involved in both physiological and pathological processes. By studying various genetic abnormalities in these organisms we can get a better insight into potential candidate genes responsible for human disease development. To this point a mouse represents one of the most used and convenient species for human disease modeling. Hundreds if not thousands of inbred, congenic, and transgenic mouse models have been created and are now extensively utilized in the research labs worldwide. Importantly, pluripotent stem cells play a significant role in developing new genetically engineered mice with the desired human disease-like phenotype. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells which represent reprogramming of somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells represent a significant advancement in research armament. The novel application of microRNA manipulation both in the generation of iPS cells and subsequent lineage-directed differentiation is discussed. Potential applications of induced pluripotent stem cell—a relatively new type of pluripotent stem cells—for human disease modeling by employing human iPS cells derived from normal and diseased somatic cells and iPS cells derived from mouse models of human disease may lead to uncovering of disease mechanisms and novel therapies.

1. Human Disease Mouse Models

Model organisms such as fruit flies, zebrafish, and mice have provided great insights into gene function in humans because they are easy to grow and genetically manipulate in the laboratory setting. By evaluating different mutations in these organisms, one can identify candidate genes that lead to disease in humans and develop models to better understand human disease pathogenesis [1]. The mouse is an ideal model organism for human disease. Not only they are physiologically similar to humans, but a large genetic reservoir of potential models of human disease has been accumulated through the generation of radiation- or chemically induced mutant loci. Multiple technological advances have dramatically advanced our skills to create mouse models of human diseases. High-resolution genetic and physical linkage maps of the mouse genome have greatly facilitated the identification and cloning of mouse disease genes. Furthermore, transgenic approaches allowed us to ectopically express or make germline mutations in virtually any gene in the mouse genome by using homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells [2, 3]. Inbred, congenic and transgenic strains are widely used in current research labs as very valuable tools to investigate human diseases pathogenesis and develop new effective therapeutical strategies.

2. Embryonic Stem (ES) and Induced Pluripotent Stem (iPS) Cells

Pluripotency is the ability of a cell to give rise to progeny representing all types of cells in an organism [4]. Murine embryonic stem cells derived from inner cell mass (ICM) of the embryo exhibit two remarkable features in culture. First, under certain conditions, they can be propagated indefinitely as a stable self-renewing population where every cell undergoes symmetrical division. This immortalized phenotype allows ES cells to be cultured over extended periods of time. Upon differentiation, this feature is lost and progeny undergoes cellular aging (Hayflick limit) as has been previously documented for all other nontransformed primary cells [5]. A second feature is that, during culture, ES cells retain their pluripotency and can differentiate into the same range of cell types as those seen in the embryo from ICM. The value of ES cells is partly due to their amenability to extensive gene manipulation. Homologous recombination between genomic and the exogenous DNA is a very inefficient and rare process, but it takes place in ES cells with relatively higher efficiency than it does in other cell types [4]. Gene targeting by homologous recombination in ES cells has improved our ability to study many biological processes [3]. Since ES cells contribute to all tissues upon injection into a recipient blastocyst, including the germline [6, 7] modification in an ES cell genome can be transmitted, by the breeding of ES cell/wild-type chimaeras, to generate mice containing the desired mutations in all cells. In this way mice with a variety of modifications such as null and point mutations, chromosomal rearrangements and large deletions have been generated. In addition, it is possible to target reporter genes under the control of specific promoters to study gene expression patterns in different cell types. Furthermore, the ability of ES cells to differentiate in vitro to many different mature somatic cell types, in combination with purification of the cell of interest by methods such as directed differentiation and lineage selection, opens up the opportunity to use these mature cell types for various basic and therapeutical applications [3]. Unfortunately, not every mouse model is permissive for true ES cells derivation. This makes it harder to investigate gene function and pathogenesis in those strains. With the advent of iPS technology this issue has been overcome.

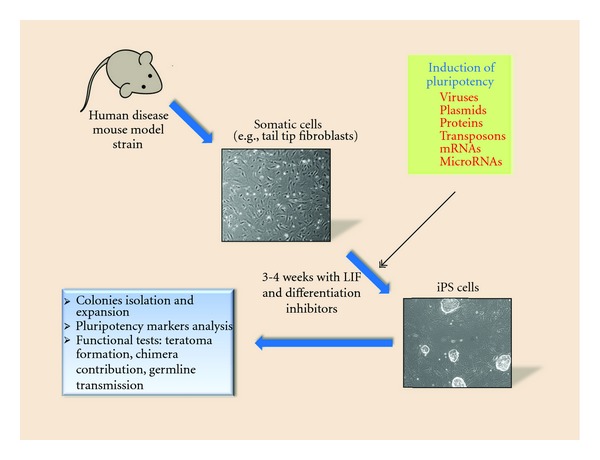

In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka initially reported the direct reprogramming of murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) to pluripotent stem cells by introducing four transcription factors [8]. Those factors, namely, Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and cMyc, that are important for self-renewal of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have been shown to reprogram both mouse and human somatic cells into ESC-like pluripotent cells (Figure 1). Since then, a large number of laboratories have derived induced pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells, and many important advances have been made [9–15]. Most importantly these iPS cells have shown properties very similar to the ones of ES cells such as pluripotency markers expression, teratoma formation, chimeras contribution, and germline transmission. Moreover, the critical advantages of iPS cells over ES cells now seem to be obvious. First of all iPS cells are being generated from the autologous recipient thus obviating the graft-versus-host problem in transplantation settings. The second benefit pertains to the ethical concerns. Unlike in the past, one can now generate ES-like iPS cells from human skin fibroblasts or hair-follicle cells without the need to resort to the human ES cell lines and potentially (in the future) apply them to the therapeutic and/or basic science approaches [13].

Figure 1.

Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from mouse model somatic cells.

3. Making Use of iPS Cells for Human Disease Modeling

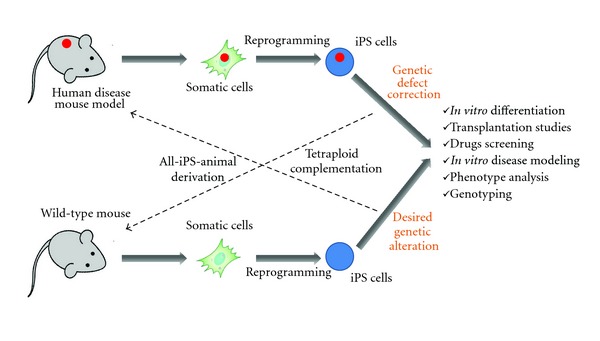

For the human disease animal modeling iPS cell technology opened the way to even wider spectrum of available mouse model strains. In 2009, Zhao et al. reported the generation of all-iPS-derived viable, fertile live-born progeny by tetraploid complementation [16] which further proved them to be useful for the development of transgenic mice strains with desired gene defects homologous to those seen in human pathology.

At present, with this valuable tool in hand one can take literally any human disease mouse strain somatic cells (e.g., tail tip fibroblasts) and induce pluripotent stem cells from them. These disease-specific iPS cells can be further used to explore given disease mechanisms both in vitro and in vivo. (Figure 2). For example, human chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (CD5+ B-cell malignancy) mouse model—New Zealand Black mouse—exhibits a defect in the miR-15a/16–1 gene on chromosome 14 which results in decreased levels of these microRNAs, which is also seen in more than 50% of CLL patients [17]. Unfortunately, this mouse strain is refractory to true ES cells derivation which makes it difficult to study the role of this microRNA gene defect in B-cell development both in vitro and in vivo. In our lab, we were able to successfully generate NZB iPS cells from spleen stromal cells. Now they can be used as subjects for gene targeting (correcting miR-15a/16–1 mutation and deletion) followed by in vitro differentiation towards B-lineage. This would help find out what role this particular gene defect plays in B-cell lymphogenesis and how its correction might alleviate malignant clonal expansion. Furthermore, NZB iPS cells with corrected miR-15a defect could be differentiated into hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) followed by their adoptive transfer into appropriate recipients in order to observe the effect of gene correction on CLL development in vivo.

Figure 2.

Mouse induced pluripotent stem cells applications for human disease mouse modeling.

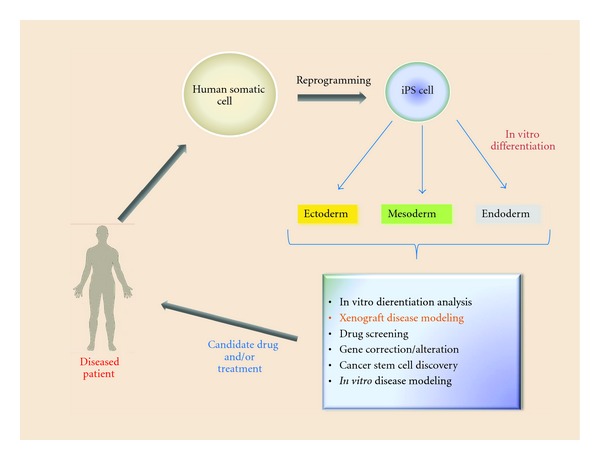

Another way to utilize iPS cells to study human diseases in animal models is xenograft transplantation assay. In this case iPS cells would be generated from patient's somatic cells (Figure 3), differentiated into desired type of cells (e.g., HSC), and transplanted into immunodeficient murine recipients. In a recent report, Yao et al. [18] have demonstrated a generation of human iPS cells with zinc-finger nuclease, mediated disruption of CCR5 locus which is known to be a coreceptor for HIV entry. These patient-specific iPS cells can now be differentiated into HSC and transplanted into animal recipients to study the role of CCR5 in HIV infection development in vivo. In another work, Lee et al. have used human iPS-derived neural stem cells (NSCs) in a mouse intracranial human glioma xenograft model [19]. In this case, iPS-derived NSCs have been used as cellular vehicles for targeted anticancer gene therapy since they will home to the brain. As a proof of principle, Hanna and colleagues have taken advantage of autologous iPS cells derived from humanized mouse model of sickle cells anemia to correct human sickle hemoglobin allele by gene-specific targeting followed by their differentiation into hematopoietic stem cells and transplantation into irradiated recipients [20]. It has been shown that mice could be rescued from disease progression after transplantation. This work has underlined the benefits of iPS technology for the combined gene and cell therapy approach to study human disease in animal models. It is needless to say that currently various labs worldwide use patient-specific iPS cells for animal modeling both in vitro and in vivo. Such pathological conditions as Huntington disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal muscular dystrophy, Gaucher disease type III, Down syndrome, type 1 diabetes, Parkinson's disease, β-thalassemia, and hepatic failure have been investigated using iPS cells generation [20–29].

Figure 3.

Human induced pluripotent stem cells applications for human disease mouse models.

4. MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small noncoding RNAs which are known to be critical for the expression control of more than a third of all protein coding genes [30] by means of binding to the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs via an imperfect match to repress their translation and/or stability [31]. They have been implicated in the regulation of many biological processes, including the stem cells self-renewal and pluripotency [32–34]. MiRNAs are generated from precursor transcripts—primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs)—that are first processed in the nucleus into an intermediate pre-miRNAs by the complex of enzymes containing Drosha and DGCR8 proteins [35–37]. The pre-miRNAs are then transported by the exportin 5-RanGTP shuttle into the cytoplasm, in which they are further processed by Dicer, into mature miRNAs [38]. In ES cells a set of microRNAs (including miR-302 and miR-17–92 clusters) closely interfere with the key pluripotency factors such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog [39, 40] thereby preventing them from differentiation and controlling their proper self-renewal potential [41]. Xu et al. have demonstrated miR-145 to control the expression of Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 and repress self-renewal of human ES cells [42]. On the other hand, c-Myc has been reported to repress miRNAs such as miR-21, let-7a, and miR-29a during reprogramming [43]. Tissue-specific miRNAs often play important roles in normal tissues and organ formation [44, 45]. More importantly for the current review, microRNAs proved to be effective tools for the iPS generation. In particular, inhibition of miR-21, let-7a, or mir-29a has been shown to enhance the reprogramming efficiency [43]. Alternatively, overexpression of the miR302/367 cluster has been shown to rapidly and efficiently reprogram both mouse and human somatic cells to iPS state without any exogenous transcription factors delivery through Oct4 gene expression activation and the suppression of Hdac2 [46]. MicroRNA gene expression profiling in human ES cells revealed specific miR-signatures of elevated expression of miR-302 cluster, miR-200 family members as well as miR-520 cluster [47]. This might imply the possibility of them to be used as tools to increase the efficiency of iPS generation without any exogenous interventions into the genomic DNA of the host cells and serve as additional iPS quality control markers. Conversely, as the regulators of gene expression microRNAs could be used to drive patient-specific iPS cells down the specific cells lineage in vitro in order to produce the required cell type to be studied [48].

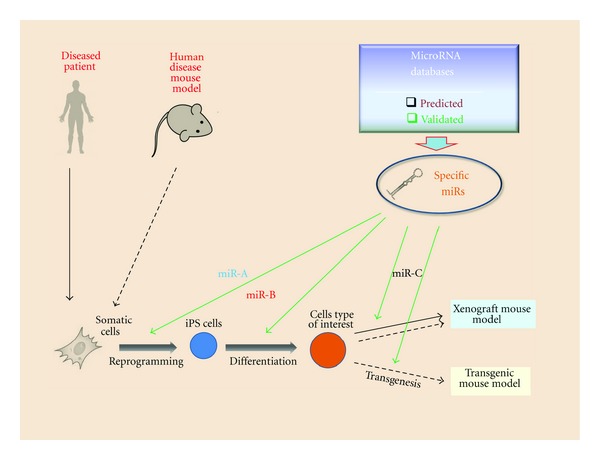

Another promise that microRNAs are holding is the development of microRNA-based gene targeting for the temporal gene-of-interest silencing [49]. For instance, aberrant expression of Pax5 (also known as BSAP), a critical regulator of B-cell development, is known to correlate with aggressive subsets of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma [50]. It has been previously shown that overexpression of miR-15a/16 reduces endogenous c-Myb levels and compromises Pax5 function [51]. Now one can produce iPS cells from Pax5-affected non-Hodgkin lymphoma patient and apply in vitro B-cell differentiation protocol along with miR-15a/16–1 delivery to evaluate lymphomagenesis in the mouse xenograft model. Potentially, the similar approach could be employed for the discovery of leukemia (or more commonly cancer) stem cells [52]. Finally, miRs can be used as biomarkers of human disease progression in mouse model settings. Overall diagram of microRNA application for mouse modeling is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

MicroRNA applications for iPS-mediated human disease mouse models.

5. Conclusion

The importance of disease mouse models and their impact on medical research is hard to overestimate. Therefore the value of animal modeling is very critical for our understanding of human disease and development of new effective approaches to therapy. Induced pluripotent stem cells hold a great promise for both basic and applied science and open the road for many more opportunities for human disease research. Coupled with the use of fine-tune regulators of gene expression, microRNAs, and mouse modeling they have a promising potential for subsequent discoveries and new therapies development in the complex field of human pathology.

References

- 1.Washington NL, Haendel MA, Mungall CJ, Ashburner M, Westerfield M, Lewis SE. Linking human diseases to animal models using ontology-based phenotype annotation. PLoS Biology. 2009;7(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000247. Article ID e1000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedell MA, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Mouse models of human disease. Part I: techniques and resources for genetic analysis in mice. Genes and Development. 1997;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hook L, O’Brien C, Allsopp T. ES cell technology: an introduction to genetic manipulation, differentiation and therapeutic cloning. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2005;57(13):1904–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niwa H. Mouse ES cell culture system as a model of development. Development Growth and Differentiation. 2010;52(3):275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohtsuka S, Dalton S. Molecular and biological properties of pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Gene Therapy. 2008;15(2):74–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley A, Evans M, Kaufman MH, Robertson E. Formation of germ-line chimaeras from embryo-derived teratocarcinoma cell lines. Nature. 1984;309(5965):255–256. doi: 10.1038/309255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson E, Bradley A, Kuehn M, Evans M. Germ-line transmission of genes introduced into cultured pluripotential cells by retroviral vector. Nature. 1986;323(6087):445–448. doi: 10.1038/323445a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science. 2008;322(5903):949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, Weir G, Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322(5903):945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1162494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seki T, Yuasa S, Oda M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell stem cell. 2010;7(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448(7151):318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, et al. Gene Targeting of a Disease-Related Gene in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem and Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai MI, Wendy-Yeo WY, Ramasamy R, et al. Advancements in reprogramming strategies for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2011;28(4):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9552-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K. Direct reprogramming 101. Development Growth and Differentiation. 2010;52(3):319–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2010.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao XY, Li W, Lv Z, et al. IPS cells produce viable mice through tetraploid complementation. Nature. 2009;461(7260):86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salerno E, Scaglione BJ, Coffman FD, et al. Correcting miR-15a/16 genetic defect in New Zealand Black mouse model of CLL enhances drug sensitivity. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2009;8(9):2684–2692. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao Y, Nashun B, Zhou T, et al. Generation of CD34+ cells from CCR5-disrupted human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Human Gene Therapy. 2012;23(2):238–242. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee EX, Lam DH, Wu C, et al. Glioma gene therapy using induced pluripotent stem cell derived neural stem cells. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2011;8(5):1515–1524. doi: 10.1021/mp200127u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318(5858):1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321(5893):1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457(7227):277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134(5):877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Beard C, et al. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136(5):964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye L, Chang JC, Lin C, Sun X, Yu J, Kan YW. Induced pluripotent stem cells offer new approach to therapy in thalassemia and sickle cell anemia and option in prenatal diagnosis in genetic diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(24):9826–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904689106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, et al. Neurons derived from reprogrammed fibroblasts functionally integrate into the fetal brain and improve symptoms of rats with Parkinson’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(15):5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to β-cells. Nature. 2008;455(7213):627–632. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behbahan IS, Duan Y, Lam A, et al. New approaches in the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells toward hepatocytes. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2011;7(3):748–759. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9216-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asgari S, Moslem M, Bagheri-Lankarani K, Pournasr B, Miryounesi M, Baharvand H. Differentiation and transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9330-y. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallanna SK, Rizzino A. Emerging roles of microRNAs in the control of embryonic stem cells and the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Developmental Biology. 2010;344(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rana TM. Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(1):23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melton C, Judson RL, Blelloch R. Opposing microRNA families regulate self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463(7281):621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature08725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tay YMS, Tam WL, Ang YS, et al. MicroRNA-134 modulates the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells, where it causes post-transcriptional attenuation of Nanog and LRH1. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):17–29. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425(6956):415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO Journal. 2002;21(17):4663–4670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng Y, Cullen BR. Sequence requirements for micro RNA processing and function in human cells. RNA. 2003;9(1):112–123. doi: 10.1261/rna.2780503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gangaraju VK, Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10(2):116–125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marson A, Levine SS, Cole MF, et al. Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;134(3):521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson KD, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Jia F, Sun N, Butte AJ, Wu JC. MicroRNA profiling of human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells and Development. 2009;18(5):749–757. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(3):380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson JA, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137(4):647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang CS, Li Z, Rana TM. microRNAs modulate iPS cell generation. RNA. 2011;17(8):1451–1460. doi: 10.1261/rna.2664111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ivey KN, Muth A, Arnold J, et al. MicroRNA regulation of cell lineages in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436(7048):214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anokye-Danso F, Trivedi CM, Juhr D, et al. Highly efficient miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(4):376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren J, Jin P, Wang E, Marincola FM, Stroncek DF. MicroRNA and gene expression patterns in the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2009;7, article 20 doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders LR, et al. miRNAs regulate SIRT1 expression during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation and in adult mouse tissues. Aging. 2010;2(7):415–431. doi: 10.18632/aging.100176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lan CC, Leong IUS, Lai D, Love DR. Disease modeling by gene targeting using MicroRNAs. Methods in Cell Biology. 2011;105:419–436. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krenacs L, Himmelmann AW, Quintanilla-Martinez L, et al. Transcription factor B-cell-specific activator protein (BSAP) is differentially expressed in B cells and in subsets of B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 1998;92(4):1308–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung EY, Dews M, Cozma D, et al. c-Myb oncoprotein is an essential target of the dleu2 tumor suppressor microRNA cluster. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2008;7(11):1758–1764. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.11.6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gunaratne PH. Embryonic stem cell MicroRNAs: defining factors in induced pluripotent (iPS) and cancer (CSC) stem cells? Current Stem Cell Research and Therapy. 2009;4(3):168–177. doi: 10.2174/157488809789057400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]