Abstract

Pancreatic tumors being either benign or malignant can be solid or cystic. Although diverse in presentation, their imaging features share commonalities and it is often difficult to distinguish these tumors. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is the most sensitive of the imaging procedures currently available for characterizing pancreatic tumors, and is especially good in identifying the smaller sized tumors. Additional applications inclusive of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) are useful in tissue sampling and preoperative staging of pancreatic tumors.

Although diagnostic capabilities have greatly evolved with advances in EUS and tissue processing technology (cytology, tumor markers, DNA analysis), differentiation of benign and malignant neoplasms, neoplastic and non-neoplastic (chronic pancreatitis) conditions, continues to be challenging.

Recent innovative applications include contrast-enhanced EUS with Doppler mode, contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS, 3-dimensinal EUS, and EUS elastography. Incorporation of these methods has improved the differential diagnosis of pancreatic tumors. Finally, a multi-disciplinary approach involving radiology, gastroenterology and surgical specialties is often necessary for accurate diagnosis and management of solid and cystic pancreatic tumors.

Key words: endosonography, eus, endoscopic ultrasound, pancreas, cystic tumors, solid tumors

Introduction

Among the increasing and diverse indications for endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), evaluation for pancreatic neoplasm remains the foremost. Neoplasms of the pancreas may be solid or cystic. Chronic pancreatitis and auto-immune pancreatitis constitute benign disease processes which may mimic solid pancreatic tumors. For detection of pancreatic tumors less than 20 mm in diameter, EUS is considered superior to computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1,2 It is a more sensitive test to detect lymph node metastasis and vascular infiltration compared to CT imaging.3 Among pancreatic tumors, EUS has better sensitivity of diagnosing pancreatic head tumors than that of body and tail of pancreas.4

Endosonography provides real-time high resolution images of cystic pancreatic lesions with morphological details. The risk of progression of pancreatic cysts to neoplasms is estimated to be 15%, necessitating further evaluation and surveillance due to risk of malignancy.4–6 Estimated prevalence of pancreatic cysts in general population is 1.2% based on observational imaging and 24% based on autopsy studies.5,7

Overall, EUS guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) is 85%–90% sensitive, 97%–100% specific and 85%–90% accurate for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. It remains extremely accurate despite previous negative tissue sampling from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous biopsies.8–11 Thus, EUS-FNA is preferentially utilized for detecting and staging of pancreatic lesions, obtain samples for confirming cytology and assess feasibility of resection.12 Over the past decade, use of EUS-FNA has evolved extensively. Numerous prospective studies have evaluated the safety of EUS-FNA. Its complication rate is estimated around 1% or less.13–15

The potential limitations of EUS include - operator dependence, restricted visualization of right hepatic lobe and peritoneal metastasis, and difficulty in tumor detection among patients with chronic pancreatitis, especially when presenting as diffuse infiltration.16

Role of EUS in the management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Ductal adenocarcinoma accounts for over 90% of pancreatic tumors.17 With a high sensitivity of 89%–100%, EUS has been successfully utilized in early detection of small pancreatic adenocarcinomas.16,18. The sensitivity of CT and MR imaging decreases for pancreatic lesions smaller than 1.5 to 2 cm. Comparatively, EUS can detect lesions with dimensions of 2 to 3 mm.2,19,20 During EUS, pancreatic adenocarcinomas appear as heterogeneous hypoechoic masses with irregular margins (Fig. 1). Dilatation of the main pancreatic duct and presence of patchy hypoechoic areas adjacent to a dilated duct (periductal hypoechoic sign) are independent predictors of pancreatic cancer.21, 22 However, relying on these morphological features alone only yields a diagnostic specificity of 53% since these features can also be seen in focal pancreatitis, neuroendocrine tumors, and metastases.23 Amongst factors which decrease sensitivity of EUS for failure to detect a pancreatic lesion, presence of acute/chronic pancreatitis is foremost (Fig. 2).16 Based on a recent meta-analysis of 29 previous studies, EUS was 73% sensitive and 90.2% specific for detecting vascular invasion.24 Although EUS is highly sensitive to detect regional lymph nodes, EUS-FNA may be necessary to provide accurate nodal staging.18

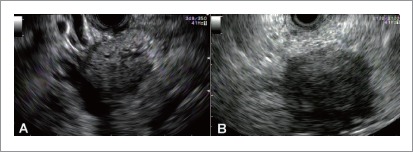

Figure 1.

Endosonography of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A: A 4.0 × 3.4 cm hypoechoic, heterogeneous mass with ill-defined borders and cystic space in the head of the pancreas; B: A 4.0×3.8 cm hypoechoic mass in the uncinate region. Fine needle aspiration confirmed diagnosis.

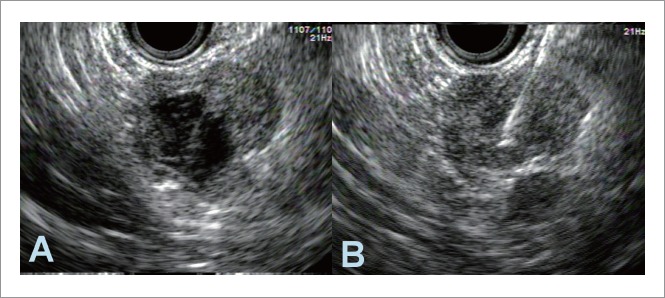

Figure 2.

Endosonography of chronic pancreatitis in the head (A), body (B) and tail (C) of the pancreas in the same patient. Chronic pancreatitis can present as a mass simulating pancreatic cancer. Conversely, calcification and lobulation in chronic pancreatitis can conceal a malignant lesion.

Role of EUS in the management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) comprise of less than 5% of all pancreatic tumors.25 The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for EUS-detection of NETs is 80%, 93% and 95% respectively.26–29 Frequently, the morphological features are sufficiently distinct to differentiate from those of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.28 The EUS appearance of pancreatic NETs frequently reveals a homogeneous, hypoechoic, hypervascular mass with distinct margins (Fig. 3). The average diameter is less than 1.5 cm. Infrequently, morphological variants of NETs on EUS include isoechoic or hyperechoic lesions, where EUS-FNA can differentiate NETs from adenocarcinomas. To assess vascularity of identified NETs, EUS with doppler mode can be employed.

Figure 3.

Endosonography of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in head (A), body (B) and tail (C) of the pancreas in the same patient. All lesions are hypoechoic well demarcated homogenous masses. Fine needle aspiration confirmed diagnosis.

Role of EUS in the management of cystic tumors of the pancreas

The neoplastic cystic pancreatic lesions (CPLs) includes intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN), mucinous cystadenomas (MCN), mucinous cystadenocarcinomas, solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPT) and few other rare types. EUS has the capability of obtaining close and high resolution imaging of CPLs. Accuracy of diagnosis of malignant or premalignant lesions by EUS alone has been reported in different series as 82–96%.30–32 However, morphologic features on EUS alone are generally considered inadequate for further characterization of CPLs or predicting their malignancy potential. The overall sensitivity of EUS-FNA for diagnosis of neoplastic CPLs varies widely and is low (<50%).32–35 The reasons put forth include, patchy distribution of malignant cyst epithelium, sampling error, on-site cytology interpretation, expertise of cytopathologist, contamination of specimen, and endoscopist's experience. On the other hand, EUS-FNA cytology is uniformly reported to have 90% specificity or more for the diagnosis of CPLs.32–34 Accuracy of EUS-FNA for diagnosis of CPLs ranges from 55% to 89%.34–36

Endosonographic appearance of microcystic serous cysteadenoma (SCA) reveals well delineated lesions with multiple, small septated fluid filled cavities, usually less than 5mm in size. In about 25% of cases, a central scar is observed.37 An underlying mucinous lesion must be however suspected if there are areas of cyst wall thickening, intramural nodules, floating debris or dilatation of pancreatic duct.31 Cyst sampling is generally not needed for diagnosis of microsystic SCA since morphological features are adequate. However, EUS-FNA can be obtained, especially from the larger cystic compartments. In contrast, macrocystic variant of SCA cannot be differentiated from mucinous cystic lesions and FNA is thus required for confirmatory diagnosis. Conservative management is recommended for small asymptomatic tumors. Given the potential for malignancy, resection is advised for large serous cystadenomas.38,39 The EUS appearance of MCNs includes a visible wall, variable thickness of the septations and infrequently, peripheral calcification (Fig. 4).40 Morphological features associated with malignancy are thick, irregular cyst wall, bigger cyst size (more than 3 cm), main duct dilatation (more than 5 mm), bulging papilla, and intramural nodules or solid components (larger than 5 mm).31,41 EUS-FNA is advised for confirmation of all suspected MCN.42 The rationale for this recommendation is the relatively high risk of malignancy which is estimated around 17.5%.43 Surgical resection is hence the usual recommendation for cysts with features of malignancy.

Figure 4.

Endosonographic images of different mucinous cysts in the pancreas. A: Multiloculated, septated cyst in pancreatic head; B: A cyst in the tail of the pancreas with a thick wall; C: A cyst in tail of the pancreas with an intramural nodule (arrow).

Role of EUS in management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas

Main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas is easily identified on EUS by diffuse dilation of the pancreatic duct (Fig. 5), mural tumor growth and occasionally intraductal filling defects due to mucin production.44 Branched duct IPMN morphology on EUS is indicated by visible communication of the cyst with the main pancreatic duct. However, in the absence of ductal communication, it is difficult to distinguish branched duct IPMN from MCNs. It is vital that an EUS-FNA is conducted if there is any intraductal mass, mural nodule or projections within the main duct or off a cyst wall. In the absence of visible lesions, the main or branch duct can be punctured for cytology and tumor markers. The limitations of EUS-FNA for detecting invasive malignancy includes low sensitivity coupled with unreliable carcinoembryonic antigen and CA 19-9 levels.45,46 Among IPMN lesions protruding 4mm or beyond within the pancreatic duct, application of intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) increases sensitivity of detecting malignancy to 68%, specificity to 89% and accuracy to 78%.47 Application of contrast enhanced EUS to predict malignant IPMN and detection of either papillary (type 3) or invasive (type 4) mural nodules provides a specificity of 93%. Increased risk of malignancy in main duct IPMN necessitates surgical removal. Expectant treatment is considered appropriate for branched duct IPMNs with diameters less than 3 cm.48

Figure 5.

Endosonography of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas in the same patient. A: Dilated main pancreatic duct (∼11.5 mm) in the head; B: uncinate process of the pancreas; C: Intraductal growth (∼9 mm, arrow) within the dilated main pancreatic duct (arrow).

EUS in other rare pancreatic tumors

Solid pseudopapillary tumors (PST) are rare pancreatic neoplasms mainly seen in young women. On EUS, it appears as a purely solid or a mixed solid and cystic mass (Fig. 6). Preoperative diagnosis with EUS-FNA is around 75%–83% accurate.49,50 Tumor size at presentation is an important determinant about malignant transformation.51

Figure 6.

Endosonography of solid-pseudo papillary tumor of the pancreas. A: An approximate 2×2 cm anechoic cyst in the tail of the pancreas with hypoechoic solid component; B: After fine needle aspiration of approximately 3 cc of clear viscous fluid, the solid component of the lesion was also sampled within the same pass.

Teratomas, choriocarcinomas, lymphoepithelial cysts, and lymphoceles should be included in rare differentials of CPLs.52,53 Primary pancreatic lymphomas are rare, constitute 0.5% of all pancreatic neoplasms. They usually are large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas presenting as mass lesions and EUS-FNA with flow cytometry is helpful in differentiating from other primary pancreatic lesions.54,55 Additional special staining and need for more tissue for accurate diagnosis may require EUS-fine needle core biopsy, percutaneous biopsy or diagnostic laparotomy. Primary lymphoma of the pancreas is usually seen on EUS as a mass occupying the pancreas and often involves the peripancreatic lymph nodes. These tend to be intensely hypoechoic masses with multiple isoechoic peripancreatic lymph nodes.56 Absence of palpable superficial and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, absence of hepatic or splenic involvement and a normal white cell count are some of the clinical features that help differentiate it from nonhodgkin's lymphoma invading the pancreas.57 Secondary pancreatic involvement from adjacent lymph node involvement is a common form of involvement.

Role of EUS in management of metastatic tumors to the pancreas

Metastatic tumors to the pancreas are rare and constitute 2% of all pancreatic malignancies. Patients usually have advanced primary malignancies. Renal cell carcinoma, lung cancer (Fig. 7), melanoma and breast cancer are some of the most commonly metastasizing cancers to the pancreas.58 Since these masses are indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, EUS-FNA for cytology is indispensible for diagnosis. Renal cell carcinoma has a propensity to metastasize many years after the initial diagnosis, thus necessitating long term surveillance.59

Figure 7.

Endosonographic images of three round, hypoechoic lesions in the head (A), body (B) and tail (C) in the same patient. Fine needle aspiration was consistent with metastatic carcinoma from a primary lung cancer.

Staging

Based on the current 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging, the pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, carcinoid tumors, and exocrine tumors are grouped under a ‘single’ staging system (Table 1).60

Table 1.

The pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, carcinoid tumors, and exocrine tumors are grouped under a ‘single’ staging system

| A ‘single’ staging system | |

| T | Primary Tumor |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, more than 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumor extends beyond the pancreas but without involvement of the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery |

| T4 | Tumor involves the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery (unresectable primary tumor) |

| N | Regional Lymph Nodes |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M | Distant Metastasis |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Accuracy of staging is augmented by EUS which improves management of pancreatic cancer. EUS is valuable in assessing peripancreatic vascular and lymph node involvement. Based on data from many large series, application of EUS in staging improves the T stage accuracy to 78–91% and the nodal (N) stage accuracy to 41–86%.1,18,61–63 EUS has highest accuracy for T-staging smaller lesions, whereas helical CT is more accurate in larger tumors.18,62–64 For nodal staging, EUS and CT scan have comparable efficacies.18,65 The four EUS features suggestive of malignant lymph node include, a hypoechoic node, round shape, well demarcated boundaries, and size > 1 cm. When present together, chances of malignancy is around 80–100%.66 For local and/or distant metastases (M staging), EUS has 42–91% sensitivity and 89–100% specificity in detection of vascular invasion.67,68 The splenic vein, portal vein and proximal superior mesenteric artery are better visualized on EUS than the other major peripancreatic vessels.68,69 The vascular invasion criteria include irregularity of the interface with the vessels, intravascular tumor growth, and nonvisualization of the vessel, with collateral circulation growth.

In recent pilot studies, contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound (CEH-EUS) has been shown to be a useful tool for visualizing microvascular pattern in pancreatic tumors. This vital information helps distinguish adenocarcinoma from other pancreatic masses.70 Further, CEH-EUS can also improve diagnostic accuracy of preoperative T-staging of pancreaticobiliary malignancies.71.

Therapeutic role of EUS

Recent years have seen emergence of newer techniques involving EUS for therapeutic benefits. EUS-guided therapy for palliation is a new and exciting area of research. Although, larger studies are needed, some of these techniques are mentioned below.

EUS-guided Celiac plexus block

This procedure uses EUS guided fine needle injection (FNI) of the celiac ganglion with a steroid and an analgesic (triamcinolone+bupivacaine) or alcohol and an analgesic (98% alcohol+bupivacaine). This blocks the afferent pain stimulus from the pancreas. It has been shown in prospective studies that there is significant reduction in pain scores and reduction in oral analgesic requirement.72–74

EUS-guided Injection of Biological and Chemotherapy Agents

The principles of therapeutic EUS are based on critical ability to guide fine-needle injection in close proximity to the target lesion. Therapies that have been investigated include: allogenic mixed lymphocyte culture,75 anti-tumor agent TNFerade,76,77 and systemic chemotherapy with EUS-FNI of ONYX-015 (replication-selective adenovirus).78 TNFerade™ (GenVec, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) is a replication-deficient adenovirus. It contains the human TNFα gene that is activated by a radiation-induced promoter.79 The treatment principle involves weekly EUS guided injection of TNFerade coupled with chemotherapy, followed by standard radiation therapy, the combination of which induces the production of tumor necrosis factor-α with resulting tumor destruction.77

EUS-Assisted Radiotherapy

Placement of gold fiducials under EUS guidance is being used to assist stereotactic radiosurgery for pancreatic cancer.80,81 EUS guided implantation of iodine 125-seeds in combination with chemotherapy has been attempted in unresectable pancreatic cancers.82 EUS-guided ablation of pancreatic tissue with photodynamic therapy or radiofrequency ablation has been attempted, but more human trials are required.83 A non-randomized study demonstrated effective placement of gold fiducials for image-guided radiation therapy in unresectable pancreatic cancer with a success rate of 88% (50 of 57 patients).84

Ablation of pancreatic cysts and tumors.

In a novel technique, EUS-guided pancreatic cyst ablation with ethanol and/or paclitaxel has been shown to achieve CT-defined cyst resolution rates of 33% to 79%.85–87 A recent study evaluated long-term follow up after EUS-guided ethanol ablation of pancreatic cysts. Durable resolution for up to 12 months was shown.88 There is new research involving alcohol ablation of isolated pancreatic insulinomas. In a recent pilot study involving six patients, EUS-guided FNI of ethanol was performed in patients with insulinomas who were not candidates for surgical resection due to comorbidities. The procedure was safe and effective during immediate follow-up.89

Newer devices and techniques used in conjunction with EUS

EUS Elastography

Elastography, is a novel technology that estimates tissue elasticity by comparing images before and after application of minimal tissue-compression. The foundation of the procedure is based on the fact that malignant tumors are generally harder than surrounding tissue. Hence, elastography may provide improved ultrasound characterization of the lesion and thereby better direction for targeted FNA. Elastography might be particularly more helpful in diagnosing challenging cases of suspicious lesions where FNA cytology is negative. A recent European multicenter study compared EUS elastography and standard EUS for diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. While the sensitivities of both the techniques were comparable at 92%, EUS elastography was significantly more specific (80%) compared to standard EUS (62%) in diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy.90 Similarly, for detection of peripancreatic lymph nodes, EUS elastography was significantly more sensitive and specific (92% and 83%, respectively) compared with standard EUS (79% and 50% respectively).90 In another recent study, 258 patients diagnosed with chronic pseudotumoral pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer focal masses were included from 13 participating centers. The EUS elastography recordings were converted into a hue histogram form (quantitative data). The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant pancreatic lesions were 96.7%, 63.8% and 90.7%, respectively.91

Newer fine needle aspiration needles and cytobrush devices

The new 22-gauge (EchoTip® ProCore™; Cook Medical., Winston-Salem, NC, USA) fine needle core biopsy needle features a core trap and a reverse bevel for tissue-core procurement. Adequate tissue can be potentially acquired utilizing this core biopsy needle when compared to a FNA needle.92 A cytobrush device (Echobrush®, Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, NC, USA) has been approved for use with a 19-gauge EUS-FNA needle in evaluation of pancreatic cysts. Lesions suitable for cytobrush use include cystic pancreatic lesions at least 2 cm in diameter that are located in the neck, body or tail of the pancreas.93,94 During EUS-FNA, cyst fluid can contain scant amount of epithelium for cytopathological assessment.95 In a prospective, blinded study comparing diagnostic yield of standard FNA to EUS-cytobrush, there was higher likelihood of obtaining intracellular mucin.93 Larger studies are needed before recommending this technique as routine practice.

Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound

The foundation of contrast-enhanced (CE) EUS involves intravenous injection of ultrasound contrast and detection of signals from micro bubbles in vessels with a very slow flow without Doppler-related artifacts. It is used to characterize tumor vascularity in the pancreas and thus distinguish pancreatic tumors from chronic pancreatitis. It can also serve as a non-invasive diagnostic technique in patients with bleeding disorders. In a study of 62 patients with ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, 92% showed hypo-vascularity of the tumor using CE-EUS. Hypo-vascularity on CE-EUS was estimated to be 92% sensitive and 100% specific as a sign of malignancy.96 With adjuvant use of a second generation ultrasound contrast agent (SonoVue®), the specificity of distinguishing benign and malignant focal pancreatic lesions increased to 93.3% using power Doppler CE-EUS compared with 83.3% for conventional EUS.97 Pancreatic NETs had a strong contrast enhancement indicative of hypervascularity and metastatic lesions to the pancreas were also likely to be hyeprvascular.97–99 In another trial, CE-EUS was found to have significantly higher sensitivity compared to power Doppler ultrasound and contrast-enhanced helical-CT for diagnosis of < 2 cm ductal carcinoma (sensitivity of 83.3% compared to 50% and 11% for power Doppler and helical-CT respectively).100 However, it is to be noted that CE-EUS cannot replace EUS-FNA for identification of malignant lymph nodes.101

Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CEH-EUS) using a prototype electronic linear array echo endoscope (xGF-UCT180; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) which is equipped with a wideband transducer improved the accuracy of detecting vascular patterns of pancreatic tumors.102,103 CEH-EUS has been shown to successfully visualize the microvascular pattern in pancreatic solid tumors in pilot studies. Potentially, this may improve preoperative T-staging of pancreatic malignancies.70, 71 Despite above advances in technology, histology remains the gold standard. However the combination of EUS-FNA and CEH-EUS could make it the most reliable procedure for assessing solid pancreatic lesions.

Tridimensional-EUS (3D-EUS)

Tridimensional (3D) endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a novel enhanced modality for interpretation of the anatomy and vascularity of the pancreatic tumors.104 The 3D images are reconstructed from a digitized set of 2D images.105 The principal advantage is accurate localization of tumors in relation to surrounding structures. Furthermore, contrast-enhanced power Doppler 3D-EUS, performed with the 3D freehand module, yields high quality images of the vascular structures related to the pancreatic tumor. Other advances like 3D-EUS elastography can also be performed through automated techniques.106 The 3D technology continues to progress, and further innovation and larger studies are necessary before conventional application. A hybrid CT-imaging and EUS study demonstrated improved localization of pancreatic lesions permitting better image interpretation.107

Conclusion

Endosonography is an operator dependent minimally invasive procedure for diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cystic and solid tumors. While a multi-disciplinary approach is required for pancreatic tumors, recent developments in the field of endosonographic imaging contribute to better diagnostic accuracy allowing improved differentiation of pancreatic lesions.

Abbreviations

- EUS

endoscopic ultrasonography

- EUS-FNA

EUS-guided fine needle aspiration

- CT

computed tomography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- ERCP

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/jig

Disclosures

No financial relationships with a commercial entity producing health-care related products and/or services relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Palazzo L, Roseau G, Gayet B, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J, Fekete F, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Results of a prospective study with comparison to ultrasonography and CT scan. Endoscopy. 1993;25:143–150. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khashab MA, Yong E, Lennon AM, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Hruban RH, et al. EUS is still superior to multidetector computerized tomography for detection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73:691–696. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosewicz S, Wiedenmann B. Pancreatic carcinoma. Lancet. 1997;349:485–489. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)05523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosch T, Lightdale CJ, Botet JF, Boyce GA, Sivak MV, Jr, Yasuda K, et al. Localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1721–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206253262601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, Kiely JM, Nakeeb A, Komorowski RA, et al. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg. 2004;239:651–657. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124299.57430.ce. discussion 7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura W, Nagai H, Kuroda A, Muto T, Esaki Y. Analysis of small cystic lesions of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:197–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02784942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gress F, Gottlieb K, Sherman S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of suspected pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:459–464. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gress FG, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, Ikenberry SO, Lehman GA. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy using linear array and radial scanning endosonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eloubeidi MA, Chen VK, Eltoum IA, Jhala D, Chhieng DC, Jhala N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of patients with suspected pancreatic cancer: diagnostic accuracy and acute and 30-day complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2663–2668. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raut CP, Grau AM, Staerkel GA, Kaw M, Tamm EP, Wolff RA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in patients with presumed pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:118–126. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(02)00150-6. discussion 27–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwhat JD, Paulson EK, McGrath K, Branch MS, Baillie J, Tyler D, et al. A randomized comparison of EUS-guided FNA versus CT or US-guided FNA for the evaluation of pancreatic mass lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:966–975. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Haddad M, Wallace MB, Woodward TA, Gross SA, Hodgens CM, Toton RD, et al. The safety of fine-needle aspiration guided by endoscopic ultrasound: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:204–208. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovannini M, Seitz JF, Monges G, Perrier H, Rabbia I. Fine-needle aspiration cytology guided by endoscopic ultrasonography: results in 141 patients. Endoscopy. 1995;27:171–177. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee LS, Saltzman JR, Bounds BC, Poneros JM, Brugge WR, Thompson CC. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic cysts: a retrospective analysis of complications and their predictors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhutani MS, Gress FG, Giovannini M, Erickson RA, Catalano MF, Chak A, et al. The No Endosonographic Detection of Tumor (NEST) Study: a case series of pancreatic cancers missed on endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2004;36:385–389. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kloppel G, Maillet B. Histological typing of pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1991;17:139–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeWitt J, Devereaux B, Chriswell M, McGreevy K, Howard T, Imperiale TF, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and multidetector computed tomography for detecting and staging pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:753–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal B, Krishna NB, Labundy JL, Safdar R, Akduman EI. EUS and/or EUS-guided FNA in patients with CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging findings of enlarged pancreatic head or dilated pancreatic duct with or without a dilated common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.026. quiz 334, 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewitt J, Devereaux BM, Lehman GA, Sherman S, Imperiale TF. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography for the preoperative evaluation of pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.020. quiz 664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka S, Nakao M, Ioka T, Takakura R, Takano Y, Tsukuma H, et al. Slight dilatation of the main pancreatic duct and presence of pancreatic cysts as predictive signs of pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Radiology. 2010;254:965–972. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SH, Ozden N, Pawa R, Hwangbo Y, Pleskow DK, Chuttani R, et al. Periductal hypoechoic sign: an endosonographic finding associated with pancreatic malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brand B, Pfaff T, Binmoeller KF, Sriram PV, Fritscher-Ravens A, Knofel WT, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound for differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic lesions, confirmed by surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1221–1228. doi: 10.1080/003655200750056736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puli SR, Singh S, Hagedorn CH, Reddy J, Olyaee M. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS for vascular invasion in pancreatic and periampullary cancers: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:788–797. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fesinmeyer MD, Austin MA, Li CI, De Roos AJ, Bowen DJ. Differences in survival by histologic type of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1766–1773. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatzipantelis P, Salla C, Konstantinou P, Karoumpalis I, Sakellariou S, Doumani I. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a study of 48 cases. Cancer. 2008;114:255–262. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardengh JC, de Paulo GA, Ferrari AP. EUS-guided FNA in the diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors before surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLean AM, Fairclough PD. Endoscopic ultrasound in the localisation of pancreatic islet cell tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson MA, Carpenter S, Thompson NW, Nostrant TT, Elta GH, Scheiman JM. Endoscopic ultrasound is highly accurate and directs management in patients with neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2271–2277. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koito K, Namieno T, Nagakawa T, Shyonai T, Hirokawa N, Morita K. Solitary cystic tumor of the pancreas: EUS-pathologic correlation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:268–276. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gress F, Gottlieb K, Cummings O, Sherman S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasound characteristics of mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:961–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frossard JL, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, Palazzo L, Amaris J, Soldan M, et al. Performance of endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1516–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brandwein SL, Farrell JJ, Centeno BA, Brugge WR. Detection and tumor staging of malignancy in cystic, intraductal, and solid tumors of the pancreas by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:722–727. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sedlack R, Affi A, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Norton ID, Clain JE, Wiersema MJ. Utility of EUS in the evaluation of cystic pancreatic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:543–547. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attasaranya S, Pais S, LeBlanc J, McHenry L, Sherman S, DeWitt JM. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and cyst fluid analysis for pancreatic cysts. JOP. 2007;8:553–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;212:432–443. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199010000-00006. discussion 44–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto T, Hirano S, Yada K, Shibata K, Sasaki A, Kamimura T, et al. Malignant serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: report of a case and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:253–256. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000152749.64526.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242:413–419. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179651.21193.2c. discussion 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarr MG, Carpenter HA, Prabhakar LP, Orchard TF, Hughes S, van Heerden JA, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of 84 mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: can one reliably differentiate benign from malignant (or premalignant) neoplasms? Ann Surg. 2000;231:205–212. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JH, Lee KT, Park J, Bae SY, Lee KH, Lee JK, et al. Predictive factors associated with malignancy of intraductal papillary mucinous pancreatic neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5353–5358. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeWitt J, Jowell P, Leblanc J, McHenry L, McGreevy K, Cramer H, et al. EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic metastases: a multicenter experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:689–696. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, Dominguez I, Bassi C, Falconi M, et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:571–579. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31811f4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Angelica M, Brennan MF, Suriawinata AA, Klimstra D, Conlon KC. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of clinicopathologic features and outcome. Ann Surg. 2004;239:400–408. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000114132.47816.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01581-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maire F, Couvelard A, Hammel P, Ponsot P, Palazzo L, Aubert A, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: the preoperative value of cytologic and histopathologic diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:701–706. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hara T, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Tsuyuguchi T, Kondo F, Kato K, et al. Diagnosis and patient management of intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor of the pancreas by using peroral pancreatoscopy and intraductal ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:34–43. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pelaez-Luna M, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Takahashi N, Clain JE, Levy MJ, et al. Do consensus indications for resection in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm predict malignancy? A study of 147 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1759–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jani N, Dewitt J, Eloubeidi M, Varadarajulu S, Appalaneni V, Hoffman B, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy. 2008;40:200–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoita A, Earls P, Williams D. Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumours - EUS FNA is the ideal tool for diagnosis. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:615–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Butte JM, Brennan MF, Gonen M, Tang LH, D'Angelica MI, Fong Y, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas. Clinical features, surgical outcomes, and long-term survival in 45 consecutive patients from a single center. J Gastrointest Surg. 15:350–357. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Capitanich P, Iovaldi ML, Medrano M, Malizia P, Herrera J, Celeste F, et al. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:342–345. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lim WC, Leblanc JK, Dewitt J. EUS-guided FNA of a peripancreatic lymphocele. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:459–462. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boni L, Benevento A, Dionigi G, Cabrini L, Dionigi R. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1107–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-4247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nayer H, Weir EG, Sheth S, Ali SZ. Primary pancreatic lymphomas: a cytopathologic analysis of a rare malignancy. Cancer. 2004;102:315–321. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flamenbaum M, Pujol B, Souquet JC, Cassan P. Endoscopic ultrasonography of a pancreatic lymphoma. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S43. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961;49:80–89. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004921319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reddy S, Wolfgang CL. The role of surgery in the management of isolated metastases to the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:287–293. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mourra N, Arrive L, Balladur P, Flejou JF, Tiret E, Paye F. Isolated metastatic tumors to the pancreas: Hopital St-Antoine experience. Pancreas. 2010;39:577–580. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181c75f74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gress FG, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, Ikenberry SO, Cummings O, Kopecky K, et al. Role of EUS in the preoperative staging of pancreatic cancer: a large single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:786–791. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yasuda K, Mukai H, Nakajima M, Kawai K. Staging of pancreatic carcinoma by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1993;25:151–155. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Legmann P, Vignaux O, Dousset B, Baraza AJ, Palazzo L, Dumontier I, et al. Pancreatic tumors: comparison of dual-phase helical CT and endoscopic sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1315–1322. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.5.9574609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakaizumi A, Uehara H, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Kitamura T, Kuroda C, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:696–700. doi: 10.1007/BF02064392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Valls C, Andia E, Sanchez A, Fabregat J, Pozuelo O, Quintero JC, et al. Dual-phase helical CT of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: assessment of resectability before surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:821–826. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.4.1780821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhutani MS, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ. A comparison of the accuracy of echo features during endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of malignant lymph node invasion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soriano A, Castells A, Ayuso C, Ayuso JR, de Caralt MT, Gines MA, et al. Preoperative staging and tumor resectability assessment of pancreatic cancer: prospective study comparing endoscopic ultrasonography, helical computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:492–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosch T, Dittler HJ, Strobel K, Meining A, Schusdziarra V, Lorenz R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound criteria for vascular invasion in the staging of cancer of the head of the pancreas: a blind reevaluation of videotapes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:469–477. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.106682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brugge WR, Lee MJ, Kelsey PB, Schapiro RH, Warshaw AL. The use of EUS to diagnose malignant portal venous system invasion by pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:561–567. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Napoleon B, Alvarez-Sanchez MV, Gincoul R, Pujol B, Lefort C, Lepilliez V, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound in solid lesions of the pancreas: results of a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:564–570. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Imazu H, Uchiyama Y, Matsunaga K, Ikeda K, Kakutani H, Sasaki Y, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS with novel ultrasonographic contrast (Sonazoid) in the preoperative T-staging for pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:732–738. doi: 10.3109/00365521003690269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wiersema MJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:656–662. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gunaratnam NT, Sarma AV, Norton ID, Wiersema MJ. A prospective study of EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for pancreatic cancer pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:316–324. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wyse JM, Carone M, Paquin SC, Usatii M, Sahai AV. Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial of Early Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Celiac Plexus Neurolysis to Prevent Pain Progression in Patients With Newly Diagnosed, Painful, Inoperable Pancreatic Cancer. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang KJ, Nguyen PT, Thompson JA, Kurosaki TT, Casey LR, Leung EC, et al. Phase I clinical trial of allogeneic mixed lymphocyte culture (cytoimplant) delivered by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle injection in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:1325–1335. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000315)88:6<1325::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murugesan SR, King CR, Osborn R, Fairweather WR, O'Reilly EM, Thornton MO, et al. Combination of human tumor necrosis factor-alpha (hTNF-alpha) gene delivery with gemcitabine is effective in models of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16:841–847. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang KJ, Lee JG, Holcombe RF, Kuo J, Muthusamy R, Wu ML. Endoscopic ultrasound delivery of an antitumor agent to treat a case of pancreatic cancer. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:107–111. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hecht JR, Bedford R, Abbruzzese JL, Lahoti S, Reid TR, Soetikno RM, et al. A phase I/II trial of intratumoral endoscopic ultrasound injection of ONYX-015 with intravenous gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McLoughlin JM, McCarty TM, Cunningham C, Clark V, Senzer N, Nemunaitis J, et al. TNFerade, an adenovector carrying the transgene for human tumor necrosis factor alpha, for patients with advanced solid tumors: surgical experience and long-term follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:825–830. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sanders MK, Moser AJ, Khalid A, Fasanella KE, Zeh HJ, Burton S, et al. EUS-guided fiducial placement for stereotactic body radiotherapy in locally advanced and recurrent pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Varadarajulu S, Trevino JM, Shen S, Jacob R. The use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided gold markers in image-guided radiation therapy of pancreatic cancers: a case series. Endoscopy. 2010;42:423–425. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jin Z, Du Y, Li Z, Jiang Y, Chen J, Liu Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided interstitial implantation of iodine 125-seeds combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:314–320. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brugge WR. EUS-guided tumor ablation with heat, cold, microwave, or radiofrequency: will there be a winner? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S212–S216. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park WG, Yan BM, Schellenberg D, Kim J, Chang DT, Koong A, et al. EUS-guided gold fiducial insertion for image-guided radiation therapy of pancreatic cancer: 50 successful cases without fluoroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gan SI, Thompson CC, Lauwers GY, Bounds BC, Brugge WR. Ethanol lavage of pancreatic cystic lesions: initial pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:746–752. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oh HC, Seo DW, Kim SC, Yu E, Kim K, Moon SH, et al. Septated cystic tumors of the pancreas: is it possible to treat them by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided intervention? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:242–247. doi: 10.1080/00365520802495537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeWitt J, McGreevy K, Schmidt CM, Brugge WR. EUS-guided ethanol versus saline solution lavage for pancreatic cysts: a randomized, double-blind study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:710–723. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.DeWitt J, DiMaio CJ, Brugge WR. Long-term follow-up of pancreatic cysts that resolve radiologically after EUS-guided ethanol ablation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Michael Levy MT. Ultrasound Guided Ethanol Ablation of Insulinomas: A New Treatment Option. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73:AB102. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giovannini M, Thomas B, Erwan B, Christian P, Fabrice C, Benjamin E, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound elastography for evaluation of lymph nodes and pancreatic masses: a multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1587–1593. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saftoiu A, Vilmann P, Gorunescu F, Janssen J, Hocke M, Larsen M, et al. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound elastography used for differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2011;43:596–603. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Komanduri SK. R. Feasibility, Specimen Adequacy, and Diagnostic Accuracy of a New EUS Guided Core Biopsy Needle: A Pilot Study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73:AB336. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Al-Haddad M, Gill KR, Raimondo M, Woodward TA, Krishna M, Crook JE, et al. Safety and efficacy of cytology brushings versus standard fine-needle aspiration in evaluating cystic pancreatic lesions: a controlled study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:127–132. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bruno M, Bosco M, Carucci P, Pacchioni D, Repici A, Mezzabotta L, et al. Preliminary experience with a new cytology brush in EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1220–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Emerson RE, Randolph ML, Cramer HM. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas is highly predictive of pancreatic neoplasia. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:457–462. doi: 10.1002/dc.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dietrich CF, Ignee A, Braden B, Barreiros AP, Ott M, Hocke M. Improved differentiation of pancreatic tumors using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.030. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hocke M, Schulze E, Gottschalk P, Topalidis T, Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in discrimination between focal pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:246–250. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Giovannini M. Endosonography: new developments in 2006. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:341–363. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ishikawa T, Itoh A, Kawashima H, Ohno E, Matsubara H, Itoh Y, et al. Usefulness of EUS combined with contrast-enhancement in the differential diagnosis of malignant versus benign and preoperative localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:951–959. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Suetomi Y, Maekawa K, Takeyama Y, Kudo M. Utility of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography for diagnosis of small pancreatic carcinomas. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kanamori A, Hirooka Y, Itoh A, Hashimoto S, Kawashima H, Hara K, et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in the differentiation between malignant and benign lymphadenopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kitano M, Kudo M, Maekawa K, Suetomi Y, Sakamoto H, Fukuta N, et al. Dynamic imaging of pancreatic diseases by contrast enhanced coded phase inversion harmonic ultrasonography. Gut. 2004;53:854–859. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.D'Onofrio M, Martone E, Malago R, Faccioli N, Zamboni G, Comai A, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of the pancreas. JOP. 2007;8:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fritscher-Ravens A, Knoefel WT, Krause C, Swain CP, Brandt L, Patel K. Three-dimensional linear endoscopic ultrasound-feasibility of a novel technique applied for the detection of vessel involvement of pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1296–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giovannini M, Bories E, Pesenti C, Moutardier V, Lelong B, Delpero JR. Three-dimensional endorectal ultrasound using a new freehand software program: results in 35 patients with rectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2006;38:339–343. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Saftoiu A, Gheonea DI. Tridimensional (3D) endoscopic ultrasound - a pictorial review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Obstein KL, Estepar RS, Jayender J, Patil VD, Spofford IS, Ryan MB, et al. Image Registered Gastroscopic Ultrasound (IRGUS) in human subjects: a pilot study to assess feasibility. Endoscopy. 2011;43:394–399. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]