Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) progresses with a deterioration of hippocampal function that is likely induced by amyloid beta (Aβ) oligomers. Hippocampal function is strongly dependent on theta rhythm, and disruptions in this rhythm have been related to the reduction of cognitive performance in AD. Accordingly, both AD patients and AD-transgenic mice show an increase in theta rhythm at rest but a reduction in cognitive-induced theta rhythm. We have previously found that monomers of the short sequence of Aβ (peptide 25–35) reduce sensory-induced theta oscillations. However, considering on the one hand that different Aβ sequences differentially affect hippocampal oscillations and on the other hand that Aβ oligomers seem to be responsible for the cognitive decline observed in AD, here we aimed to explore the effect of Aβ oligomers on sensory-induced theta rhythm. Our results show that intracisternal injection of Aβ1–42 oligomers, which has no significant effect on spontaneous hippocampal activity, disrupts the induction of theta rhythm upon sensory stimulation. Instead of increasing the power in the theta band, the hippocampus of Aβ-treated animals responds to sensory stimulation (tail pinch) with an increase in lower frequencies. These findings demonstrate that Aβ alters induced theta rhythm, providing an in vivo model to test for therapeutic approaches to overcome Aβ-induced hippocampal and cognitive dysfunctions.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive function [1–5] that correlates with the extracellular accumulation of amyloid beta protein (Aβ) [1, 4, 5]. Deterioration of hippocampal function, likely induced by Aβ oligomers, contributes to the memory deficits associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) [5–8]. Normal hippocampal function is strongly dependent on a 3 to 10 Hz oscillatory activity, namely, the theta rhythm [9–11]. Theta oscillations have been associated with various cognitive processes in several species, including humans [9–11]. Theta rhythm abnormalities are usually related to memory deficits and pathological changes in the brain [12–14]. In fact, subjects with AD show a typical “electroencephalographic slowing” that includes increased slow rhythms and decreased fast rhythms [6, 13, 15, 16]. Regarding theta rhythm, AD patients show increased theta rhythm at rest [6, 15, 16], but they also show a decrease in induced-theta rhythm; both of these changes in theta rhythm correlate with a reduced cognitive performance [17]. A similar contradictory scenario has been found in transgenic mice that overproduce Aβ and exhibit AD-like symptoms [18, 19]. The complex relationships between AD pathology and theta rhythms have been explained by the theta rhythm heterogeneity that exists both in humans and in mice [12, 20]. Experimentally, the reduction in resting hippocampal theta rhythm has been mimicked by Aβ application, both in vitro [21–23] and in vivo [24, 25]. However, just one previous study has shown that intracerebroventricular injection of monomers of a short Aβ sequence (peptide 25–35) decreases the power of the induced theta rhythm [26]. This finding still needs to be confirmed because different Aβ peptides, as well as their aggregation states, differentially affect similar hippocampal rhythms [27]. Thus, in this study we explored the effect of oligomers of the full-length Aβ sequence (peptide 1–42) on induced theta rhythm in vivo. The use of Aβ1–42 oligomers has more relevance for the study of AD-related neural network disruption since early symptoms of AD are better correlated with the amount of soluble Aβ than other histopathological makers [2, 3]. Our data show that intracisternal application of Aβ slows down sensory-induced hippocampal oscillations, supplanting theta oscillations with a slower rhythm.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental protocols were approved by The Local Committees of Ethics on Animal Experimentation (CICUAL-Cinvestav and INB-UNAM) and followed the regulations established in the Mexican Official Norm for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals (“Norma Oficial Mexicana” NOM-062-ZOO-1999). For these experiments, Wistar rats (300–330 g) were briefly and lightly anesthetized with ether vapor just before receiving a single, intracisternal injection of 5 μL of either vehicle (F12 medium) or oligomerized Aβ1–42 (5 and 50 pmoles). The injector was connected to a Hamilton syringe mounted on dual perfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus Co., MA, USA). Animals were allowed to recover for 1 h after the intracisternal injection. Then, the animals were anesthetized with urethane (1.3 g/Kg; i.p.) and secured in a Kopf stereotaxic frame with the nose bar positioned at −3.3 mm [28, 29]. A bipolar electrode was implanted in the left dorsal hippocampus (A = −3.6 mm L = 2.4 mm and V = 4.2 mm from bregma, according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson [30]) using standard stereotaxic procedures. The electrodes were attached to male connector pins, which were inserted into a connector strip. Hippocampal field recordings were amplified and filtered (highpass, 0.5 Hz; lowpass, 1.5 KHz) with a wideband AC amplifier (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA, USA). Theta rhythm was elicited with sensory stimulation, consisting of a tail pinch produced by a plastic clamp positioned on the tail 2 cm from its base. A tail pinch, lasting 75 s, was applied each 10–20 min for at least 1 h. At the end of the hippocampal field recordings, all animals were processed for histological location of the electrode [28, 29, 31]. The recording site was visually confirmed to be located in the hippocampal fissure.

All recordings were digitized at 3–9 KHz and stored on a personal computer with an acquisition system from National Instruments (Austin, TX, USA) by using custom-made software designed in the LabView environment. The recordings obtained were analyzed offline by performing classical power spectrum analysis with a resolution of 0.61 Hz [26, 27, 32]. Segments of 30 sec were analyzed using a Rapid Fourier Transform Algorithm, with a Hamming window, in Clampfit (Molecular Devices). The power spectra during the tail pinch, at any given frequency, were also divided by their corresponding prestimulus power spectra and expressed as percentage of control (100% meaning no difference between tail-pinch and prestimulus power spectra). The mean difference spectra were then calculated by averaging the differences obtained in any given group [33–35]. For time-frequency analysis, segments of 40 s were analyzed using the Morlet wavelet basis and plotted as a time-frequency representation (TFR) [26, 32].

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). To analyze the data, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare control versus tail-pinch spectra in the same group of animals. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare groups. A value of P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

3. Results

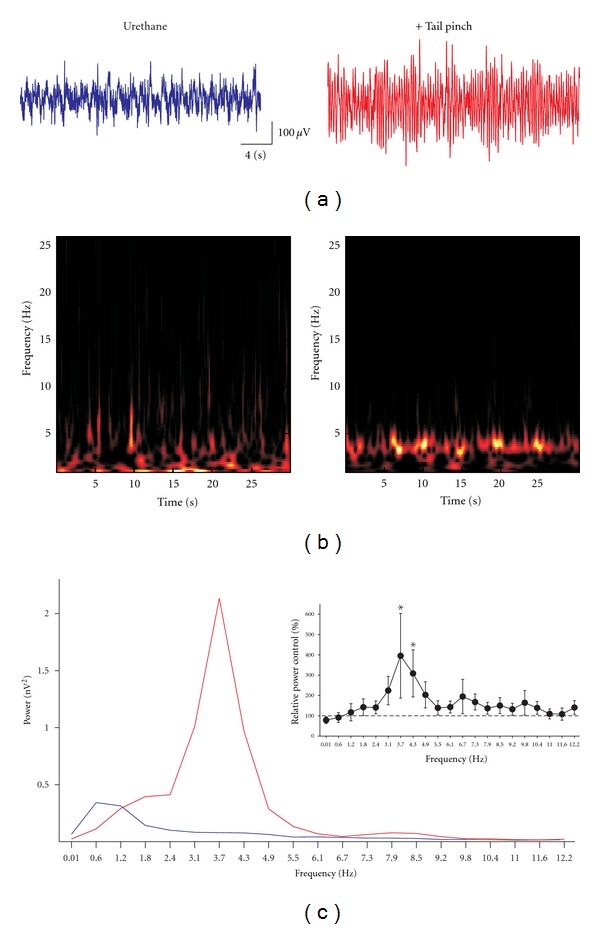

Under urethane anesthesia, hippocampal local field potential showed a pattern of irregular activity (Figure 1(a); blue trace) that resembles the so-called large amplitude irregular activity (LIA) and that corresponds to the activity observed during immobility and slow-wave sleep [9, 12]. Such activity turns into more steady, oscillatory activity upon sensory stimulation (tail pinch; Figure 1(a); red trace). The spectrograms show that basal hippocampal activity under urethane anesthesia consists of a variable mixture of frequency components that vary over time (Figure 1(b)). In contrast, upon sensory stimulation, hippocampal activity exhibits a more constant oscillatory pattern (Figure 1(b)). The power spectrum shows that basal hippocampal activity under urethane anesthesia peaks at 2.5 ± 0.5 Hz, whereas theta rhythm has a frequency of 3.0 ± 0.4 Hz (Figure 1(b)). Quantification of the change in power upon tail pinch, compared with basal hippocampal activity, shows that sensory stimulation significantly increases the power in the low theta range (3.7–4.3 Hz) (Figure 1(c); inset).

Figure 1.

Sensory stimulation induces hippocampal theta oscillations. (a) Representative field recordings obtained from the hippocampal fissure in a urethane-anaesthetized rat at rest (blue recording) and upon sensory stimulation (red trace). (b) and (c) show the spectrograms and the power spectra, respectively, of the traces shown in (a). The blue power spectrum corresponds to the recording at rest, and the red power spectrum corresponds to the recording upon sensory stimulation. The inset in (c) shows the quantification of the change in power upon sensory stimulation, compared with basal hippocampal activity. *Indicates a significant difference compared to the control (P < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

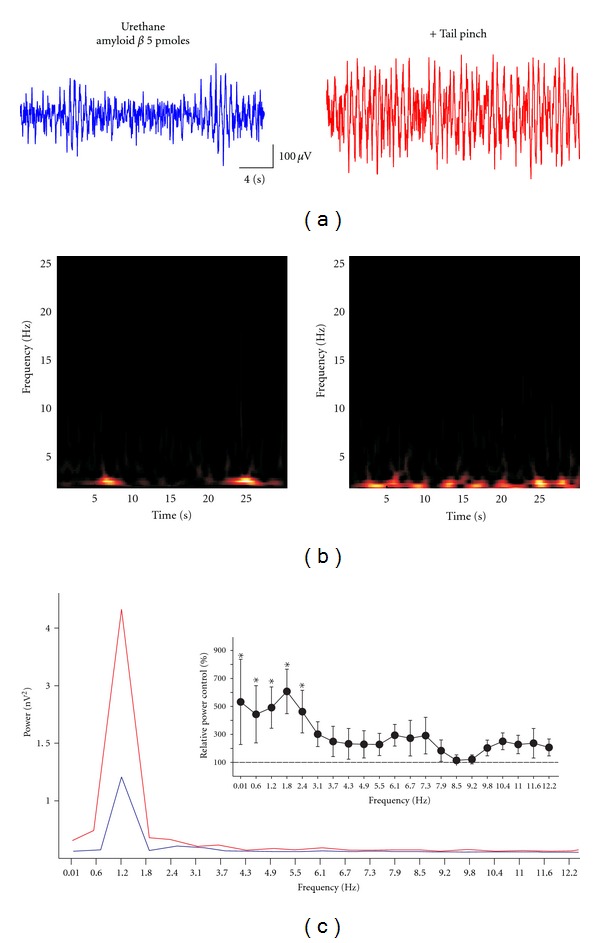

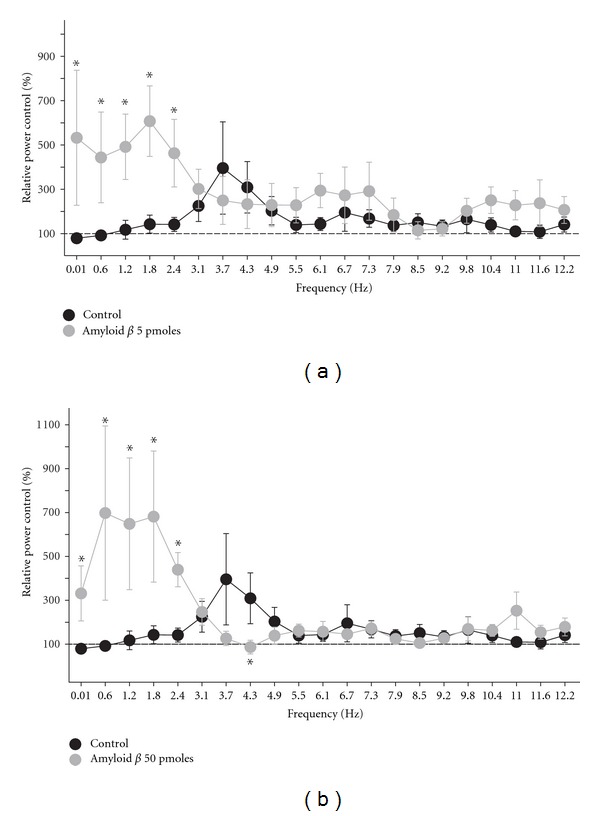

When testing the effects of Aβ oligomers on hippocampal activity, we did not find any significant difference in the hippocampal activity compared with control animals, due to the high variability among groups, either in power or peak frequency, due to the high variability among groups (Table 1). As illustrated in Figure 2, the hippocampal activity recorded after intracisternal injection of 5 pmoles of Aβ oligomers is still characterized by a pattern of nonstationary, irregular activity under urethane anesthesia (Figure 2(a); blue trace). This activity also turns into a more homogeneous oscillatory activity upon sensory stimulation (tail pinch; Figures 2(a), 2(b); red trace). The spectrograms show that basal hippocampal activity under urethane anesthesia consists of a variable mixture of frequency components that change over time (Figure 2(b)). In contrast, upon sensory stimulation hippocampal activity turns into a more stationary, oscillatory state (Figure 2(b)). On average, in animals injected with 5 pmoles of Aβ oligomers and under urethane anesthesia, basal hippocampal activity peaks at 3.4 ± 0.6 Hz, and the tail pinch-induced rhythm has a frequency of 3.4 ± 0.6 Hz (Table 1). As mentioned, neither the power nor the peak frequency of hippocampal activity changed upon Aβ application in either basal or sensory-stimulated conditions (Table 1). However, quantification of the change in power upon tail pinch shows significant changes compared with basal hippocampal activity. Sensory stimulation in Aβ-treated animals significantly increases the power in low frequencies (0.01–2.4 Hz) (Figure 2(c); inset and Figure 3). In fact, the increase in power of those frequencies was significantly higher in Aβ-treated animals than in control (vehicle-treated) animals (Figure 3). Although sensory-induced theta rhythm was not significantly changed relative to control animals by injection of 5 pmoles of Aβ, it was significantly reduced at 4.3 Hz by a higher dose, 50 pmoles of Aβ (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Power and peak frequency of the hippocampal activity recorded in anaesthetized animals in control conditions and after the intracisternal injection of amyloid beta (Aβ). No significant differences were observed among or within groups.

| Condition | Power (nV2) | Peak Frequency (Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| Urethane | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| + Tail pinch | 5.1 ± 2.6 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| Urethane + Aβ 5 pmoles | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.6 |

| + Tail pinch | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 0.6 |

| Urethane + Aβ 50 pmoles | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 3.9 ± 0.1 |

| + Tail pinch | 3.6 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 0.4 |

Figure 2.

Effect of 5 pmoles amyloid beta on the sensory-induced hippocampal theta oscillations. (a) Representative field recordings obtained from the hippocampal fissure in a urethane-anaesthetized rat at rest (blue recording) and upon sensory stimulation (red recording). (b) and (c) show the spectrograms and the power spectra, respectively, of the traces shown in (a). The blue spectrum corresponds to the recording at rest, and the red power spectrum corresponds to the recording upon sensory stimulation. The inset in (c) shows the quantification of change in power upon sensory stimulation, compared with basal hippocampal activity. *Indicates a significant difference compared to control (P < 0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Figure 3.

Amyloid beta slows, in a dose-dependent manner, the oscillatory activity induced by sensory stimulation. Change in power induced by sensory stimulation in control rats (black circles; n = 9) compared to that in amyloid beta-injected rats (gray circles; n = 6). Animals were injected with two doses of amyloid beta. With 5 pmoles (a), the increase in power, upon sensory stimulation, shifts towards slow frequencies. Injection of 50 pmoles of amyloid beta (b) also shifts the increase in power, upon sensory stimulation, towards slow frequencies, and it also significantly reduces the increase in theta rhythm. *Indicates a significant difference compared to control rats (P < 0.05; Mann-Whitney U test).

4. Discussion

Our results show that intracisternal application of Aβ1–42 oligomers does not produce any significant effect on spontaneous hippocampal activity, but it disrupts the hippocampal activation induced by sensory stimulation. Aβ-treated animals do respond to sensory stimulation (tail pinch), but the increase occurs in lower frequencies than in control animals. These findings may correlate with the EEG slowing observed in AD patients [6, 13, 15, 16] as well as with the reduction in evoked theta rhythm [17] that was also observed in AD patients. In our previous report, we demonstrated that intracerebroventricular injection of monomers of the short Aβ sequence (25–35) reduced the power of induced theta rhythm [26]. However, in that study we did not find the change in theta frequency observed here. The simplest explanation for this difference is that oligomers of Aβ1–42 may act on different cellular targets and produce different effects than monomers of Aβ25–35 [27]. If so, without ignoring the advantages of using monomers of Aβ25–35 [23, 26], we believe that the use of Aβ1–42 oligomers may represent a more valid model to explore some of the changes related to AD pathology. A second potential explanation is that in the current study we used intracisternal application of Aβ in contrast to the intracerebroventricular injections used previously [26]. It has been found that intracerebroventricular and intracisternal administration of the same substance do not always produce the same effect, probably due to differences in the brain structures preferentially reached by the injection in those sites, as well as to the different concentrations of the injected substance reached at those structures [36–42].

Our results are in agreement with previous findings that direct application of Aβ, either in the medial septum or in the hippocampus, reduces theta-rhythm power both in vivo and in vitro [22–26, 43]. However, in our hands, intracisternal application of Aβ also shifts the frequency of sensory-evoked oscillations to the left. Several factors have been associated with the reduction in theta power. For instance, we have shown that this reduction is related to a reduction in intrahippocampal glutamatergic transmission [22, 26], but the reduction in power also has been associated with the blockade of several K+ channels [23, 44] or with Aβ-induced changes in septal neuron firing [23–25]. The shift in frequency induced by Aβ might be related to changes in the activity of interneurons in the hippocampus or elsewhere [23–25] or to the effect of Aβ on transient potassium currents [44]. Overall, the effects of Aβ on hippocampal theta rhythm seem to involve a complex mixture of effects on several neural types within several neural networks. It is well known that hippocampal theta rhythm could be affected by a decoupling of one or several autonomous oscillators within the hippocampus [45] or in other interconnected neural networks [24, 25]. Correlative in vitro experiments are required to corroborate this hypothesis and to determine viable molecular targets to prevent Aβ-induced neural network disruption.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dorothy Pless for reviewing the English version of this paper. They also thank José Rodolfo Fernandez and Arturo Franco for technical assistance. This work was sponsored by grants (to F. Peña-Ortega) from DGAPA IA201511; CONACyT 59187,151261; and from the Alzheimer's Association NIRG-11-205443.

References

- 1.Braak H, Braak E. Diagnostic criteria for neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 1997;18(4, supplement 1):S85–S88. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, et al. Soluble amyloid β peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Pathology. 1999;155(3):853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Näslund J, Haroutunian V, Mohs R, et al. Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid β-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. JAMA. 2000;283(12):1571–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peña F, Gutiérrez-Lerma AI, Quiroz-Baez R, Arias C. The role of β-amyloid protein in synaptic function: implications for Alzheimer's disease therapy. Current Neuropharmacology. 2006;4(2):149–163. doi: 10.2174/157015906776359531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298(5594):789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babiloni C, Frisoni GB, Pievani M, et al. Hippocampal volume and cortical sources of EEG alpha rhythms in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. NeuroImage. 2009;44(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein WL, Krafft GA, Finch CE. Targeting small A β oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer’s disease conundrum? Trends in Neurosciences. 2001;24(4):219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ondrejcak T, Klyubin I, Hu NW, Barry AE, Cullen WK, Rowan MJ. Alzheimer’s disease amyloid β-protein and synaptic function. NeuroMolecular Medicine. 2010;12(1):13–26. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bland BH, Colom LV. Extrinsic and intrinsic properties underlying oscillation and synchrony in limbic cortex. Progress in Neurobiology. 1993;41(2):157–208. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90007-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahana MJ, Seelig D, Madsen JR. Theta returns. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11(6):739–744. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(01)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klimesch W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: a review and analysis. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;29(2-3):169–195. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colom LV. Septal networks: relevance to theta rhythm, epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;96(3):609–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson CE, Snyder PJ. Electroencephalography and event-related potentials as biomarkers of mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2008;4(1, supplement 1):S137–S143. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. Neural synchrony in brain disorders: relevance for cognitive dysfunctions and pathophysiology. Neuron. 2006;52(1):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babiloni C, Cassetta E, Binetti G, et al. Resting EEG sources correlate with attentional span in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25(12):3742–3757. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C, Wahlund LO, Dierks T, Julin P, Winblad B, Jelic V. Discrimination of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment by equivalent EEG sources: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;111(11):1961–1967. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummins TDR, Broughton M, Finnigan S. Theta oscillations are affected by amnestic mild cognitive impairment and cognitive load. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;70(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jyoti A, Plano A, Riedel G, Platt B. EEG, activity, and sleep architecture in a transgenic AβPP swe/PSEN1A246E Alzheimer’s disease mouse. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;22(3):873–887. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Ikonen S, Gurevicius K, Van Groen T, Tanila H. Alteration of cortical EEG in mice carrying mutated human APP transgene. Brain Research. 2002;943(2):181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin J. Theta rhythm heterogeneity in humans. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2010;121(3):456–457. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akay M, Wang K, Akay YM, Dragomir A, Wu J. Nonlinear dynamical analysis of carbachol induced hippocampal oscillations in mice. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2009;30(6):859–867. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balleza-Tapia H, Huanosta-Gutiérrez A, Márquez-Ramos A, Arias N, Peña F. Amyloid β oligomers decrease hippocampal spontaneous network activity in an age-dependent manner. Current Alzheimer Research. 2010;7(5):453–462. doi: 10.2174/156720510791383859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leão RN, Colom LV, Borgius L, Kiehn O, Fisahn A. Medial septal dysfunction by Aβ-induced KCNQ channel-block in glutamatergic neurons. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.07.013. Neurobiology of Aging. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colom LV, Castañeda MT, Bañuelos C, et al. Medial septal β-amyloid 1–40 injections alter septo-hippocampal anatomy and function. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31(1):46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villette V, Poindessous-Jazat F, Simon A, et al. Decreased rhythmic GABAergic septal activity and memory-associated θ oscillations after hippocampal amyloid-β pathology in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(33):10991–11003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6284-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peña F, Ordaz B, Balleza-Tapia H, et al. Beta-amyloid protein (25–35) disrupts hippocampal network activity: role of Fyn-kinase. Hippocampus. 2010;20(1):78–96. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adaya-Villanueva A, Ordaz B, Balleza-Tapia H, Márquez-Ramos A, Peña-Ortega F. Beta-like hippocampal network activity is differentially affected by amyloid beta peptides. Peptides. 2010;31(9):1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peña F, Tapia R. Relationships among seizures, extracellular amino acid changes, and neurodegeneration induced by 4-aminopyridine in rat hippocampus: a microdialysis and electroencephalographic study. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72(5):2006–2014. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peña F, Tapia R. Seizures and neurodegeneration induced by 4-aminopyridine in rat hippocampus in vivo: role of glutamate- and GABA-mediated neurotransmission and of ion channels. Neuroscience. 2000;101(3):547–561. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carmona-Aparicio L, Peña F, Borsodi A, Rocha L. Effects of nociceptin on the spread and seizure activity in the rat amygdala kindling model: their correlations with 3H-leucyl-nociceptin binding. Epilepsy Research. 2007;77(2-3):75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romcy-Pereira RN, de Araujo DB, Leite JP, Garcia-Cairasco N. A semi-automated algorithm for studying neuronal oscillatory patterns: a wavelet-based time frequency and coherence analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2008;167(2):384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrew C, Fein G. Induced theta oscillations as biomarkers for alcoholism. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2010;121(3):350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.11.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macdonald JS, Mathan S, Yeung N. Trial-by-trial variations in subjective attentional state are reflected in ongoing prestimulus EEG alpha oscillations. Frontiers in Psychology. 2011;2, article 82 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JJ, Craggs MD. Intracranial self-stimulation, cortical arousal, and the sensorimotor neglect syndrome. Experimental Neurology. 1979;65(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czimmer J, Million M, Taché Y. Urocortin 2 acts centrally to delay gastric emptying through sympathetic pathways while CRF and urocortin 1 inhibitory actions are vagal dependent in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 2006;290(3):G511–G518. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00289.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gunther O, Kovacs GL, Szabo G, Schwarzberg H, Telegdy G. Differential effect of vasopressin on open-field activity and passive avoidance behaviour following intracerebroventricular versus intracisternal administration in rats. Acta Physiologica Hungarica. 1988;71(2):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunther O, Schwarzberg H. Influence of intracerebroventricularly and intracisternally administered vasopressin on the hypothalamic self-stimulation rate of the rat. Neuropeptides. 1987;10(4):361–367. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(87)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harland D, Gardiner SM, Bennett T. Differential cardiovascular effects of centrally administered vasopressin in conscious Long Evans and Brattleboro rats. Circulation Research. 1989;65(4):925–933. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee H, Naughton NN, Woods JH, Ko MCH. Characterization of scratching responses in rats following centrally administered morphine or bombesin. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2003;14(7):501–508. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000095082.80017.0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozawa M, Aono M, Moriga M. Central effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) on gastric motility and emptying in rats. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1999;44(4):735–743. doi: 10.1023/a:1026661825333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park KH, Long JP, Cannon JG. Evaluation of the central and peripheral components for induction of postural hypotension by guanethidine, clonidine, dopamine2 receptor agonists and 5-hydroxytryptamine(1A) receptor agonists. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1991;259(3):1221–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mugantseva EA, Podolski IY. Animal model of Alzheimer’s disease: characteristics of EEG and memory. Central European Journal of Biology. 2009;4(4):507–514. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou X, Coyle D, Wong-Lin K, Maguire L. Beta-amyloid induced changes in A-type K+ current can alter hippocampo-septal network dynamics. doi: 10.1007/s10827-011-0363-7. Journal of Computational Neuroscience. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goutagny R, Jackson J, Williams S. Self-generated theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12(12):1491–1493. doi: 10.1038/nn.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]