Abstract

We report a universal method for the surface-initated polymerization (SIP) of a antifouling polymer brush on various classes of surfaces, including noble metals, metal oxides and inert polymers. Inspired by the versatility of mussel adhesive proteins, we synthesized a novel bifunctional tripeptide bromide (BrYKY) which combines an atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) initiating alkyl bromide with l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) and lysine. Simple dip-coating of substrates with variable wetting properties and compositions, including Teflon®, in a BrYKY solution at pH 8.5 led to formation of a thin film of cross-linked BrYKY. Subsequently, we showed that the BrYKY layer initiated the ATRP of a zwitterionic monomer, sulfobetaine methacrylate (SBMA) on all substrates, resulting in high density antifouling pSBMA brushes. Both BrYKY deposition and pSBMA grafting were unambiguously confirmed by ellipsometry, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and goniometry. All substrates that were coated with BrYKY/pSBMA dramatically reduced bacterial adhesion for 24 h and also resisted mammalian cell adhesion for at least 4 months, demonstrating the long-term stability of the BrYKY anchoring and antifouling properties of pSBMA. The use of BrYKY as a primer and polymerization initiator has the potential to be widely employed in surface grafted polymer brush modifications for biomedical and other applications.

Introduction

Fouling of surfaces in the form of protein, cell and bacteria adsorption poses serious challenges for biomedical devices. For example, protein adsorption on biosensors can reduce sensitivity;1 bacterial colonization of catheters results in significant morbidity and mortality;2 and adhesion of macrophages on pacemaker leads can lead to degradation and ultimately pacemaker dysfunction.3 To mitigate biofouling, biomaterial surfaces can be grafted with antifouling polymer brushes such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), polyzwitterions, polypeptoids and polysaccharides.4–6

When pre-formed polymers are “grafted-to” a surface, steric hindrance limits the grafting density, which is an important parameter in antifouling performance.7 Surface initiated polymerization (SIP) involves growth of antifouling polymer brushes from initiators immobilized on surfaces, allowing higher densities and thicknesses and leading to better antifouling performance of “grafted-from” compared to “grafted-to” polymer brushes.8 Various chemistries for initiator immobilization have been exploited, often chosen according to the characteristics of the substrate- for example, organosilanes on silicon oxide, phosphonates on iron oxide and thiols on gold.6 However, the immobilization of initiators on polymeric surfaces is challenging, especially for inert polymers like polyethylene (PE) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which often require harsh chemical or physical activating steps such as hydrogen plasma, ozone pretreatment and UV radiation.6

A universal method to immobilize initiators onto all classes of materials for the SIP of antifouling polymer brushes is desirable, especially for modifying biomedical devices composed of multiple materials. In this respect we are inspired by mussels, as they are well known for their ability to attach to wet surfaces in coastal environments through the use of adhesive proteins that adhere even to PTFE.9 Extensive research by Waite and coworkers on the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) have revealed that mussel adhesive proteins found close association with the substrate interface contain a high concentration of l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), an amino acid post-translationally modified from tyrosine.10–13 Consequently, catechols, as found in the side chain of DOPA, have been used by us and other groups to anchor initiators for SIP of antifouling polymer brushes.14,15 However, these earlier studies were limited to metal surfaces and did not include nonmetallic substrates.

Aside from DOPA, the interfacial mussel adhesive protein Mefp-5 also contains a significant number of lysines10, which are frequently located adjacent to DOPA residues, suggesting that lysine could play a role in mussel adhesion. It was found that the catechol of the DOPA can form covalent bonds with amines at high pH.16,17 Additionally, dopamine and other catecholamines are known to polymerize at alkaline pH into thin adherent coatings on many materials.18,19 Recently, Zhu and Edmonson used dopamine functionalized with 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide for deposition onto metals and polystyrene substrate, followed by the SIP of PMMA and PHEMA.20 However, this method was not comprehensively investigated on other polymeric substrates and the resulting polymer brushes were not assessed for antifouling or any applications.

In this work, we designed a novel catecholamine peptide ATRP initiator, BrYKY, with the goal of substrate-independent SIP of antifouling polymer brushes. ATRP is a widely used approach to SIP due to its robustness and versatility in choice of initiator, catalyst, solvent and monomer.21 Zwitterionic coatings are a promising alternative to the widely used PEG and PEG derivatives for antifouling modification.22,23 For the monomer, we chose sulfobetaine methacrylate (SBMA), as recent reports showed that zwitterionic polymer brushes based on SBMA and carboxybetaine methacrylate (CBMA) have antifouling performance comparable to or better than OEG based brushes.24–27 Both experimental and theoretical studies have suggested that the excellent antifouling properties of zwitterionic betaines stem from the opposite charges being highly hydrated.28,29 However, while OEG based brushes have been demonstrated to resist cell adhesion for up to 50 days,30 the longest investigation of antifouling properties of polybetaines that we are aware of was that of CBMA for 8 days.31 Here, we show that the peptide ATRP initiator BrYKY successfully immobilized on a variety of metal oxides, noble metals and polymers in one step. The BrYKY layer then initiated the ATRP of pSBMA polymer brushes which maintained antifouling properties for at least 4 months.

Materials and Methods

Materials

N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), dichloromethane (DCM), triisopropylsilane (TIS), piperidine, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), bicine, 2-bromo-2-methylpropionic acid, copper(I) bromide, copper(II) bromide, 2,2'-bipyridine, sulfobetainemethacrylate, poly-L-lysine (MW 150–300 kDa) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and Contrad® 70 detergent was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Acetonitrile (ACN) with 0.1% trifluroacetic acid was purchased from Honeywell Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI). Methanol (MeOH) and 2-propanol (IPA) was purchased from VWR International (West Chester, PA). Rink amide-MBHA resin, Fmoc-DOPA(acetonide)-OH and Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH, O-benzotriazole-N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (HBTU) were obtained from Novabiochem (San Diego, CA). 3T3-Swiss albino fibroblasts, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), calf bovine serum (CBS), penicillin/streptomycin and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), calcein-AM and Syto 9 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) was obtained from BD Diagnostic Systems (Sparks, MD). Ultra pure water (U.P. H2O) with resistivity ≥ 18.2 MQ-cm was obtained from a NANOpure Infinity System from Barnstead/Thermolyne Corp. (Dubuque, IA). 4 inch prime silicon wafers were obtained from Ultrasil Corporation (Hayward, CA). Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), high molecular weight polyethylene (PE) and polycarbonate (PC) were purchased from McMaster-Carr (Elmhurst, IL) as thin sheets with thicknesses around 0.5 mm. The PC sheets were manufactured from Makrolon®, a bisphenol A derived polycarbonate from Bayer MaterialScience (Sheffield, MA). Tecothane®, a biomedical grade polyurethane (PU) was generously donated by Lubrizol Advanced Materials (Cleveland, OH).

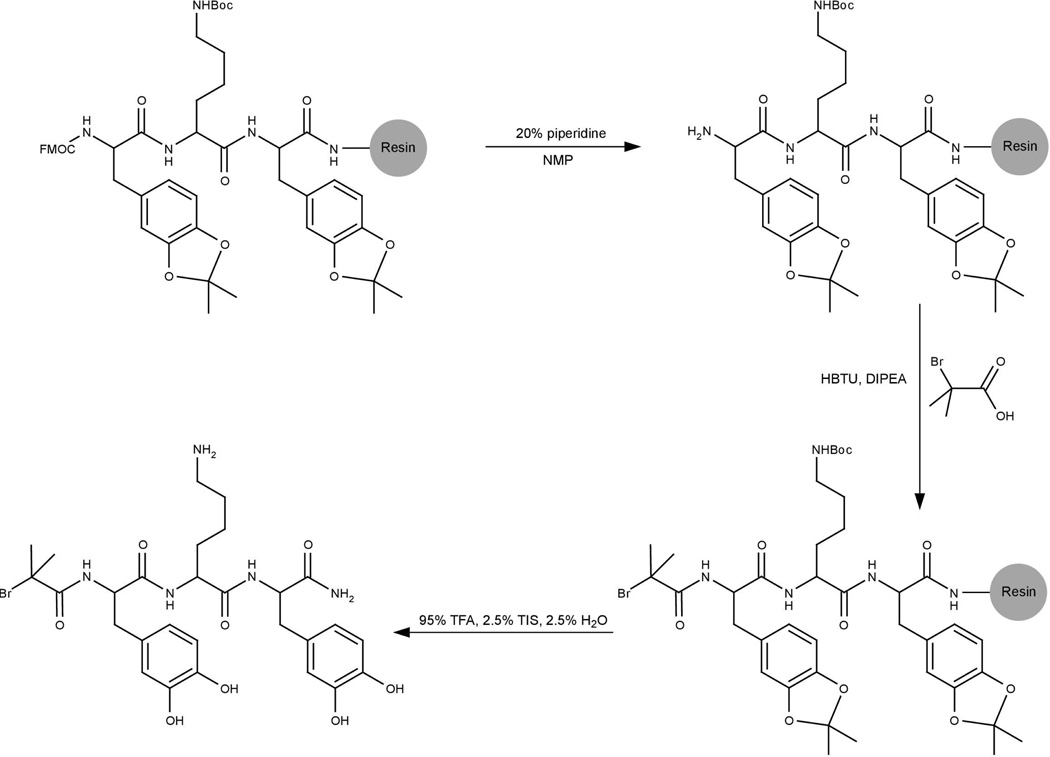

Br-DOPA-Lysine-DOPA (BrYKY)synthesis

The tripeptide initiator BrYKY was synthesized on Rink amide-MBHA resin as seen in Scheme 1 (Note: Y and K are used to denote the locations of DOPA and Lys residues, respectively, in the modified tripeptide). Standard Fmoc strategy of solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) was used to couple Fmoc-DOPA(acetonide)-OH and Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH onto the resin with NMP as the solvent. Fmoc deprotection of the N-termini was achieved with 20% (v/v) piperidine in NMP. HBTU was used as the coupling reagent. The final coupling reaction of 2-bromo-2-methylpropionic acid to the deprotected N-terminus was also achieved in NMP and with HBTU as the coupling reagent. Deprotection of side-chains and cleavage from the resin was simultaneously achieved using 95% (v/v) TFA, 2.5% H2O and 2.5% TIS. A rotary evaporator was used to remove most of the TFA from the resulting mixture, which was then redissolved in 50% (v/v) ACN/H2O, frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. The product was purified by preparative reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) with a Vydac C18 column. Fractions containing the product were collected and solvent was partly removed using centrifugal evaporation. The remaining liquid was frozen and lyophilized. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and analytical RP-HPLC were used to identify the mass and purity of the final product.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis and chemical structure of BrYKY, starting with the protected tripeptide already formed on resin using standard solid phase peptide synthesis.

Substrate Preparation

Silicon wafers were coated with 20 nm thick TiO2 (as measured by ellipsometry) by electron beam evaporation (Edwards Auto 500; <10-5 Torr). 50 nm of gold was sputtered onto silicon wafers with a Ti adhesion layer using a Lesker Nano-38 (Pittsburgh, PA). All substrates were cut into 1 cm by cm pieces and cleaned via sonication for ten minutes each in 5% (v/v) Contrad® 70 solution, IPA and U.P. H2O sequentially, then dried in a stream of N2.

For initiator immobilization, the cleaned substrates were immersed into a solution of 1 mM BrYKY in a 10 mM bicine buffered solution at pH 8.5. Polymeric substrates that had specific gravity close to that of water were allowed to float upside down, held up by surface tension. The well plate was then placed onto an orbital shaker for 2 hours, after which the substrates were removed and thoroughly rinsed with U.P. H2O to remove unbound initiators and dried with N2.

ATRP

Substrates were placed individually into glass tubes which where then placed into a nitrogen glove bag which was purged and refilled with nitrogen 3 times. In a flask, U.P. H20 was bubbled with argon for at least 15 mins before the addition of CuBr (5 mM), CuBr2 (1 mM), bpy (12 mM) and SBMA (500 mM). SI-ATRP was started by the addition of 2 mL of ATRP solution into each glass tube. The reaction was stopped by the removal of the glass tubes from the glove bag and exposure of the solution to oxygen, which caused the color of the solution to change from reddish brown to blue green. Substrates were then rinsed thoroughly with U.P. H2O, and dried with a stream of N2.

Coating Characterization

Thicknesses of initiator and pSBMA layers were measured using an ESM-300 spectroscopic ellipsometer (J.A. Woollam, Lincoln, NE) at incident angles of 65°, 70° and 75° using a range of wavelengths from 400–1000 nm. The spectra were fitted using multilayer models in the CompleteEASE software (J.A. Woollam). A 15 A base layer of native silicon oxide was assumed. All other layers above were fitted using a Cauchy model to the refractive index and thickness of the new layer. The coefficients of the Cauchy equation used were initially fixed for organic layers (An = 1.45, Bn = 0.01, Cn = 0), and then An and Bn were allowed to be fitted to determine more accurate values.

XPS spectra were collected on an Omicron ESCALAB (Omicron, Taunusstein, Germany) equipped with a monochromated Al Kα (1486.8 eV) 300W X-ray source, 1.5 mm circular spot size at an ultrahigh vacuum (<10-8 Torr). A electron flood gun was used at 0.004 to 0.005 mA to counter charging effects in the samples. Samples were mounted onto sample studs with adhesive copper tape. The takeoff angle were fixed at 45° for all measurements. Binding energies were calibrated using the C(1s) signal at 284.6 eV. CasaXPS 2.3.15 software was used to quantify the peak areas, specifically employing a Shirley background subtraction and the summation of 90% Gaussian and 10% Lorentzian function. Atomic sensitivity factors from the in-built Scofield library32 were used to normalize the peak areas to derived atomic composition.

A contact angle goniometer (Rame-hart, Mountain Lakes, NJ) and the supplied DropImage Advanced software was used to measure advancing contact angle measurements on all substrates using the sessile drop method on dry samples. An auto pipetting system (Rame-hart, Mountain Lakes, NJ) was used with advancing step size of 1µl and output rate of 20 seconds per full stroke. 1 second was allowed for the drop to equilibrate before measurement.

Bacteria Adhesion Assay

2 different strains of bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (RP62A), were first expanded overnight in tryptic soy broth (30 g/L). The bacteria were centrifuged at 4000 rcf for 5 mins and rinsed with DPBS twice before being resuspended at a concentration of 1E8 CFU/ml in DPBS. Each substrate was placed into a 24-well plate, UV sterilized for 15 mins, covered with 1 ml of the bacteria suspension, incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, rinsed gently with DPBS, stained with 2 µM Syto-9 in U.P. H2O for 15 mins and then imaged.

3T3 Mouse Fibroblast Cell Culture

3T3-Swiss albino fibroblasts obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in T40 flasks (BD Falcon) containing DMEM with 10% calf bovine serum (CBS) and 100 µg/mL of penicillin and 100 U/ml of streptomycin and passaged every 3–4 days. Substrates were placed into 24-well tissue culture polystyrene plates (TCPS), sterilized with germicidal UV light for 10 mins, pretreated with 500 µl of DMEM with 10% CBS and allowed to equilibrate for 30 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, fibroblasts were harvested by treatment with trypsin-EDTA for 3 minutes, resuspended in DMEM with 10% CBS, counted with a bright-line hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA), and then diluted in media accordingly. Each well was then seeded with 500 µl of media containing 5500 cells to achieve a surface density of 3000 cells/cm2. The plate was then incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2, after which non-adherent cells were removed by rinsing twice in PBS. The adhered fibroblasts were then exposed to 2.5 µM calcein-AM in complete PBS for 45 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2 before being transferred to a new TCPS well plate containing fresh media for imaging. For long-term cell culture, substrates were reseeded with cells as described above twice a week, for 4 months.

Imaging

A Leica epifluorescent microscope (W. Nuhsbaum Inc., McHenry, IL) equipped with a SPOT RT digital camera (Diagnostics Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) was used to capture 3 images on random locations on each of the 3 substrates for a total of 9 images per condition. Using ImageJ (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MA), each image was thresholded to determine the area that was covered by cells or bacteria which was then expressed as the percentage of the total area of the image. For the long-term cell culture, confluency is marked as 100% cell area coverage.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of BrYKY initiator

BrYKY was synthesized using the Fmoc strategy of solid phase peptide synthesis from Rink amide MBHA resin. As the dihydroxyls of the DOPA are known to be important in the adhesion mechanism,16 we used acetonide-protected DOPA amino acids to prevent their oxidation to quinones during synthesis. The side chain amine of the lysine amino acid was protected by Boc so that coupling of the initiator moiety was confined to the deprotected N-termini of the tripeptide. 2-bromo-2-methylpropionic acid was added in excess together with HBTU as a coupling agent and in the presence of DIPEA (Scheme 1). This allowed 2-bromo-2-methylpropionyl to be coupled to the N-termini through an amide bond, which is hydrolytically more stable compared to an ester bond. Preparative RP-HPLC was used to purify the crude product. The ESI-MS spectra of purified BrYKY confirmed the molecular weight of 651 g/mol and matched the correct isotopic distribution profile which was calculated from the natural occurrences of the 79Br, 81Br and 13C isotopes (Figure S1). Analytical RP-HPLC determined the purity of the product to be greater than 97% (Figure S2).

BrYKY initiator immobilization on substrates

Immobilization of BrYKY was achieved by immersing substrates into a pH 8.5 solution of 1 mM BrYKY. After 16 h, XPS analysis (Table 1) showed that the surfaces of all substrates gained N and Br content while completely losing substrate-specific signals such as Ti, Au, Si and F, indicating that the surfaces were coated with a film thicker than the analysis depth of XPS (~10 nm). These atomic compositions approached that of the theoretical atomic composition of BrYKY, indicating that BrYKY was deposited onto the substrate surfaces as a multi-layer with thickness greater than 10 nm. Minimal variation in atomic composition between the BrYKY layers on different substrates suggested that these layers were similar and formed regardless of the underlying substrate.

Table 1.

XPS atomic compositions of pristine substrates, substrates after 16 h BrYKY modification and after 2 h SI-ATRP of SBMA, and theoretical atomic compositions of BrYKY and SBMA.

| C | O | Ti/Si/Au/F | Br | N | S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TiO2 +BrYKY +ATRP |

29.8 71.1 66.0 |

52.2 17.4 23.4 |

17.3 0 0 |

- 1.9 0 |

0.7 9.6 5.2 |

- - 5.5 |

|

SiO2 +BrYKY +ATRP |

12.8 70.2 67.3 |

27.7 17.8 22.1 |

59.6 0 0 |

- 1.9 0 |

- 10.3 5.0 |

- - 5.6 |

|

Au +BrYKY +ATRP |

53.6 70.6 67.2 |

8.6 17.7 22.1 |

37.8 0 0 |

- 1.6 0 |

- 10.2 5.1 |

- - 5.6 |

|

PC +BrYKY +ATRP |

85.6 72.2 69.1 |

14.4 17.0 21.5 |

- - - |

- 1.8 0 |

- 9.0 4.8 |

- - 4.7 |

|

PE +BrYKY +ATRP |

100 71.3 68.1 |

0 17.6 21.9 |

- - - |

- 1.8 0 |

- 9.3 4.9 |

- - 5.2 |

|

PTFE +BrYKY +ATRP |

24.3 71.3 67.6 |

0 17.6 22.2 |

75.7 0 0 |

- 1.9 0 |

- 9.2 5.0 |

- - 5.2 |

|

PU +BrYKY +ATRP |

85.8 73.0 68.2 |

11.3 18.8 22.2 |

- - - |

- 1.2 0 |

2.9 7.0 4.8 |

- - 4.7 |

|

BrYKY (theory) SBMA (theory) |

66.7 61.1 |

19.0 27.8 |

- - |

2.4 - |

11.9 5.6 |

- 5.6 |

For substrates with smooth reflective surfaces that allowed ellipsometry measurements (TiO2, SiO2, Au and PC), a kinetic study of BrYKY deposition was performed to monitor film growth. As displayed in Figure 1, the thicknesses of the BrYKY layer initially increased rapidly but leveled off by 16 h to thicknesses of 15.3 ± 0.6, 12.7 ± 0.8, 15.3 ± 0.7, 19.1 ± 1.8 nm on TiO2, SiO2, Au and PC respectively. This growth behavior was typical of catecholamines, such as dopamine, under similar conditions.18

Figure 1.

Growth of the BrYKY initiator layer thickness as measured using ellipsometry on Au TiO2, SiO2 and PC.

Advancing water contact angles on all substrates converged from their widely ranging pristine values to near 60° after BrYKY modification, agreeing with the XPS data that a similar film had formed on all substrates (Figure 2). Taken together, these data provide evidence that BrYKY is able to successfully adhere on all tested materials such as metal oxides, noble metals and polymers.

Figure 2.

Advancing water contact angles of pristine substrates, substrates after BrYKY modification and after SI-ATRP of SBMA. Samples with contact angles of less than 10° are indicated by “+”.

BrYKY lnitiates SI-ATRP of SBMA

A kinetic study of SI-ATRP of SBMA was performed on the BrYKY coated substrates for up to 4 h, with ellipsometry on Au, TiO2 and SiO2 showing that the growth in thickness was linear across 4 h with R2 values of 97.0%, 97.6% and 98.3% respectively, indicating that the polymerization growth is well controlled at about 10 nm/h (Figure 3). For PC, the total thickness reached a maximum of 30 nm at 2 h before decreasing upon further ATRP, which we attribute to delamination of the BrYKY/pSBMA coating from the substrate. Therefore, all subsequent experiments were performed on substrates that underwent ATRP of SBMA for 2 h, at which point the ellipsometric thickness of the combined BrYKY/pSBMA layer was between 30 and 44 nm. XPS analysis revealed the appearance of S and an increase in O/C ratio on all substrates, confirming that pSBMA had been grafted to the BrYKY layer (Table 1). However, the typical O/C ratio of ~ 0.32 is lower than the 0.46 theoretical O/C ratio of SBMA. The disparity could be due to adventitious hydrocarbon contamination and also possibly that the BrYKY and pSBMA layers are partially interpenetrating, resulting in an atomic composition between that of BrYKY and SBMA. Advancing contact angles were found to be less than 10 degrees on all pSBMA substrates, agreeing with the formation of hydrophilic pSBMA. As a negative control, bare TiO2 substrates treated under the same ATRP conditions were found to have negligible increases in thickness as measured by ellipsometry.

Figure 3.

Total thicknesses of the BrYKY/pSBMA layer showing growth of the pSBMA polymer brush thickness as measured using ellipsometry on Au, TiO2, SiO2 and PC.

pSBMA on all substrates resists bacterial adhesion

Previous studies have shown that pSBMA polymer brushes have excellent antifouling properties.24,33 To our best knowledge, this is the first report of pSBMA polymer brushes grafted on polymeric substrates such as PC, PE, PTFE and PU. Thus it would be of interest to determine if the pSBMA polymer brush initiated by BrYKY possessed the same antifouling abilities as pSBMA initiated via other anchoring methods for substrates such as Au and SiO2.24,34 In these experiments, substrates were modified with BrYKY for 16 h followed by 2 h of SI-ATRP of SBMA, and static bacterial adhesion measured using both gram negative and gram positive species. On bare substrates, gram negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa covered 10 – 40% of available surface area after 24 h (Figure 4). With the BrYKY/pSBMA modification, adhesion was significantly reduced to less than 0.2% for all substrates. Similarly, on bare substrates, gram positive Staphylococcus epidermidis covered 30 – 50% of surfaces after 24 h whereas adhesion was significantly reduced to less than 0.3% for all BrYKY/pSBMA modified substrates (Figure 5). These results showed that pSBMA polymer brushes initiated by BrYKY were of sufficiently high density to dramatically reduce adhesion of both gram negative and gram positive bacteria.

Figure 4.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesion on bare substrates and substrates modified with BrYKY/pSBMA.

Figure 5.

Staphylococcus epidermidis adhesion on bare substrates and substrates modified with BrYKY/pSBMA.

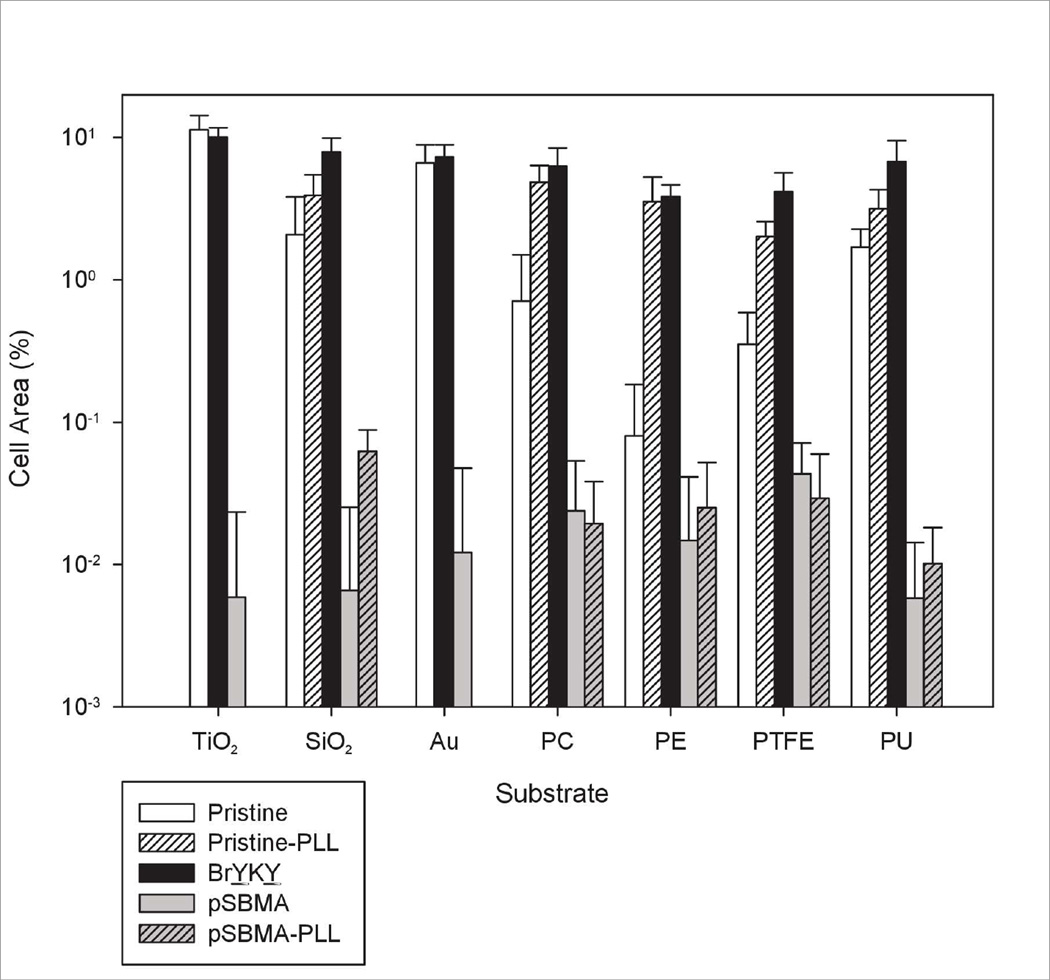

Short Term 3T3 Cell Adhesion

Resistance to mammalian cell adhesion on the BrYKY initiated pSBMA surfaces was also investigated using 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells. 24 h after seeding, bare TiO2, Au, SiO2 and PU surfaces had 11%, 7%, 2% and 2% cell coverage respectively as seen in Figure 6. On bare PC, PE and PTFE substrates, cells adhered poorly, at 0.7%, 0.08% and 0.4% cell coverage respectively. When all 7 types of substrates were coated with the BrYKY initiator layer, cell adhesion improved to coverages between 4% and 10%. Substrates that were grafted with pSBMA displayed significantly reduced cell adhesion to below 0.05% across all substrates. However, for SiO2 and the 4 polymeric substrates, the reduction was less obvious due to low cell adhesion on the bare substrates, which could be due to preferential adsorption of albumin from the media acting as a passivating layer.35 To increase the contrast in antifouling performance of the pSBMA coatings on these 5 substrates, a duplicate set of bare substrates was treated with poly-l-lysine (PLL), commonly used to promote cell adhesion on surfaces. With PLL treatment prior to seeding, cell adhesion on the bare substrates increased to 2–5% cell coverage or more, while cell adhesion on the PLL-treated pSBMA coated substrates remained below 0.1%.

Figure 6.

3T3 cell adhesion on pristine substrates (with or without PLL modification), substrates modified with BrYKY and substrates modified with BrYKY/pSBMA (with or without PLL modification).

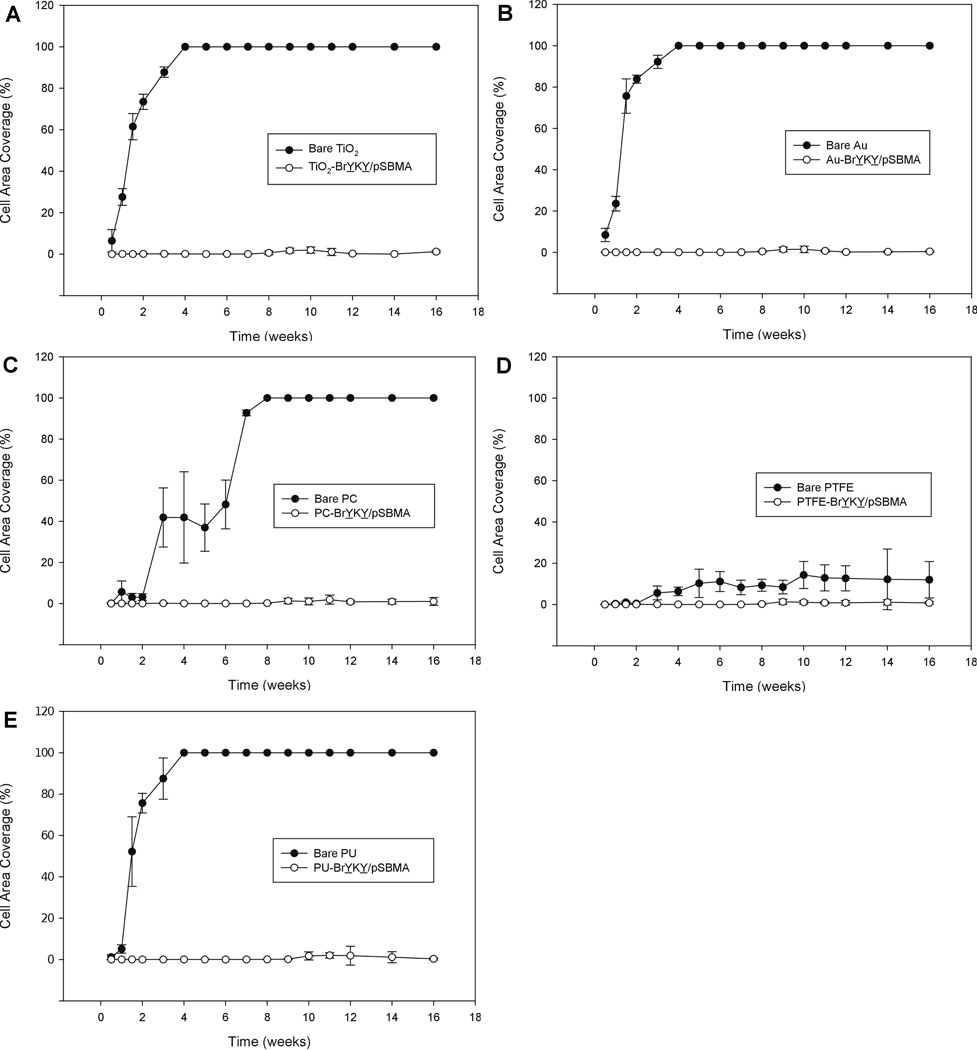

Long-Term Cell Resistance of BrYKY/pSBMA

Surfaces modified with polymer brushes that initially show excellent antifouling properties can become fouled over longer periods of time if protein adsorption is kinetically slow but thermodynamically favored,36 or if the polymer brush and/or its anchoring mechanism degrade. Thus, even though the 24 h bacterial and mammalian cell adhesion experiments indicated excellent short term antifouling performance of the BrYKY/pSBMA layer, one cannot simply extrapolate these results to the long-term. To determine the long-term stability and performance of pSBMA initiated and anchored by BrYKY, TiO2, Au, PC, PTFE and PU substrates grafted with BrYKY/pSBMA were subjected to a 4 month cell culture challenge, in which surfaces were exposed to fresh 3T3 cells twice weekly. As seen in Figure 7, Bare TiO2, Au and PU substrates became confluent by 4 weeks; bare PC substrates became confluent by 8 weeks; bare PTFE substrates did not become confluent but maintained cell coverages between 8–14% after week 4. In comparison, all 5 substrates that were grafted with pSBMA nearly eliminated cell adhesion across the whole 4 month period, with cell coverages mostly below 1%. A few time points showed up to 2% cell coverage on pSBMA surfaces, but were due to weakly attached cells which did not remained permanently adhered. These results demonstrated that the BrYKY/pSBMA layers had excellent stability and antifouling performance. To the best of our knowledge, this has been the longest in vitro time scale study of the antifouling properties of a polybetaine, with the previous being an 8 day study of pCBMA.31

Figure 7.

Long-term 3T3 cell adhesion on BrYKY/pSBMA modified (A) TiO2, (B) Au, (C) PC, (D) PTFE, (E) PU compared to bare controls over a period of 4 months.

Previously, we reported TiO2 surfaces grafted with poly(oligo ethylglycol methyl ether methacrylate) (pOEGMEMA) brushes via a catecholic initiator, enabling the resistance of cell adhesion for about a month before becoming confluent after 2.5 months.37 It was suggested that cleavage of the ester bonds in pOEGMEMA led to the loss of fouling resistance. Given that ester bonds are also found in pSBMA and taking into consideration recent reports that even covalently anchored polymer brushes can quickly detach,38 it is possible that fouling of the pOEGMEMA brushes occurred due to detachment of individual catechol anchors. We believe that the enhanced long-term antifouling performance of the BrYKY/pSBMA coating is primarily due to the improved anchoring mechanism, and/or improved antifouling properties of pSBMA compared to pOEGMEMA.

Effect of pH and mechanism of adhesion

Depending on the substrate, different mechanisms can be responsible for the adhesion of BrYKY to the surface. On metal oxide surfaces, adhesion could be due to catechol-metal coordination and electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged oxide surface and positively charged lysines. For aromatic polymers such as PC, π-π interaction with the catechol could contribute to adhesion.9 However, aside from van der Waals forces, there are no specific interactions expected between BrYKY and inert substrates such as PTFE. We believe that the ability of BrYKY to successfully adhere on inert substrates is a result of its ability to cross-link, allowing cooperative adhesion.

To further understand the mechanism of BrYKY deposition and adhesion, we compared the reaction of BrYKY at pH 5 and pH 8.5. Using MALDI-MS, we detected dimers and multimers of up to 6 units in a 1 mM solution of BrYKY after 2 h at pH 8.5 but not at pH 5 (Figure S3), showing that cross-linking of BrYKY occurs at high pH. For the dimers at m/z of 1301, there was a mass loss of 4 a.m.u., which could be due to cross-linking at 2 sites possibly from amines with catechols and catechols with catechols. There were also peaks at m/z of 1222 and 1140, corresponding to dimers with the loss of 1 or 2 bromines, possibly due to heterolysis of the Br induced by the MALDI laser or to SN1 reactions between the amines and bromides of the BrYKY molecules. In contrast, at pH 5, no multimers were detected except for a trace of dimers, indicating that cross-linking is suppressed at low pH.

In comparison to using dopamine reacted with alkyl bromide as an initiator,20 BrYKY has the advantage of two catechols and one amine, providing 3 possible sites for cross-linking with another BrYKY. This can increase the degree of cross-linking and cohesion while still allowing for unreacted catechols to provide adhesion to surfaces. In support of this hypothesis, preliminary experiments with coatings derived from a dipeptide initiator containing one DOPA and one Lys (i.e., BrKY) did not form stable coatings (data not shown).

To show that the cross-linking of BrYKY was crucial to the successful anchoring of BrYKY, we then attempted immobilizing 1 mM BrYKY in pH 5 buffer for 16 h on the same substrates. Ellipsometric (Figure S4) and XPS (Table S1) measurements indicated that BrYKY deposition was either much thinner, in the range of a monolayer, or completely absent on substrates such as PTFE. Subsequently, we attempted SI-ATRP of SBMA on TiO2, SiO2 and PC modified with BrYKY at pH 5, and found much less pSBMA than when modified with BrYKY at pH 8.5.

This comparison showed that cross-linking of BrYKY, induced by high pH which shifts the equilibrium of catechols towards reactive quinones that can cross-link with amines and other catechols,16 is crucial in the BrYKY deposition process and subsequently for the strong anchoring of pSBMA. When cross-linked, BrYKY molecules on the surface are held in place by other BrYKY molecules and thus can no longer detach individually, resulting in an overall increase in stability. This cooperative adhesion can explain how BrYKY deposited at pH 8.5 can anchor strongly onto inert substrates such as PTFE even without specific interactions other than van der Waals forces, and could be similar to the way coatings derived from dopamine and norepinephrine are able to coat virtually any substrate.18,19

Conclusion

BrYKY, a mussel-inspired tripeptide conjugated with a tertiary bromide, was polymerized at high pH onto metal oxide, metallic, and polymeric substrates to form a thin ATRP initiator layer. Subsequently, SBMA was grafted onto the BrYKY-modified substrates using ATRP, forming dense pSBMA polymer brushes. This method is compatible with a wide variety of substrates as both the initiator immobilization and ATRP steps are performed in fully aqueous conditions, avoiding harsh solvents which could swell or dissolve polymeric substrates. The pSBMA/BrYKY modification significantly reduced bacterial and mammalian cell adhesion on all tested substrates, and were found to be stable in cell culture conditions for at least 4 months. The increased adhesion stability and versatility of BrYKY is believed to be due to the cohesion between BrYKY molecules. This universal strategy for the facile grafting of antifouling polymer brushes for long-term performance will be a valuable tool in combating fouling on existing and future biomaterials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01 EB005772 and R37 DE014193 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). J.K. was supported by a National Science Scholarship from the A*STAR Graduate Academy of Singapore. XPS analysis was performed at the Nuance Keck-II facility of Northwestern University. ESI-MS and MALDI-MS analysis were performed at the Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center (IMSERC) of Northwestern University.

Footnotes

(Table S1) XPS atomic compositions of pristine substrates, substrates modified with BrYKY at pH 5 and consequently attempted SI-ATRP of pSBMA. (Figure S1) ESI-MS spectrum of purified BrYKY. (Figure S2) Analytical RP-HPLC chromatogram of purified BrYKY (97% purity). (Figure S3) MALDI-MS spectrum of 1 mM BrYKY solution at pH 8.5 and pH 5 after 1h. (Figure S4) Ellipsometric thicknesses of films on substrates after BrYKY modification at pH 5 and subsequently SI-ATRP of SBMA. This is information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Wisniewski N, Reichert M. Methods for reducing biosensor membrane biofouling. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2000;18:197–219. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren JW. Catheters-associated Urinary Tract Infections. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 1997;11:609–622. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Q, Topham N, Anderson JM, Hiltner A, Lodoen G, Payet CR. Foreign-body giant cells and polyurethane biostability: In vivo correlation of cell adhesion and surface cracking. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1991;25:177–183. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820250205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbert DL, Hubbell JA. Surface Treatments of Polymers for Biocompatibility. Annual Review of Materials Science. 1996;26:365–294. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee I, Pangule RC, Kane RS. Antifouling Coatings: Recent Developments in the Design of Surfaces That Prevent Fouling by Proteins, Bacteria, and Marine Organisms. Advanced Materials. 2011;23:690–718. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbey R, Lavanant L, Paripovic D, Schüwer N, Sugnaux C, Tugulu S, Klok H-A. Polymer Brushes via Surface-Initiated Controlled Radical Polymerization: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, and Applications. Chemical Reviews. 2009;109:5437–5527. doi: 10.1021/cr900045a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szleifer I. Polymers and proteins: interactions at interfaces. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science. 1997;2:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao B, Brittain W. Polymer brushes: surface-immobilized macromolecules. Progress in Polymer Science. 2000;25:677–710. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waite JH. Nature’s underwater adhesive specialist. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives. 1987;7:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waite JH, Qin X. Polyphosphoprotein from the adhesive pads of Mytilus edulis. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2887–2893. doi: 10.1021/bi002718x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papov VV, Diamond TV, Biemann K, Waite JH. Hydroxyarginine-containing Polyphenolic Proteins in the Adhesive Plaques of the Marine Mussel Mytilus edulis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:20183–20192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waite JH. The DOPA Ephemera: A Recurrent Motif in Invertebrates. Biol Bull. 1992;183:178–184. doi: 10.2307/1542421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee BP, Messersmith PB, Israelachvili JN, Waite JH. Mussel-Inspired Adhesives and Coatings. Annual Review of Materials Research. 2011;41:99–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan X, Lin L, Dalsin JL, Messersmith PB. Biomimetic Anchor for Surface-Initiated Polymerization from Metal Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15843–15847. doi: 10.1021/ja0532638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li G, Xue H, Cheng G, Chen S, Zhang F, Jiang S. Ultralow Fouling Zwitterionic Polymers Grafted from Surfaces Covered with an Initiator via an Adhesive Mussel Mimetic Linkage. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2008;112:15269–15274. doi: 10.1021/jp8058728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Scherer NF, Messersmith PB. Single-molecule mechanics of mussel adhesion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:12999–13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605552103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waite JH, Andersen NH, Jewhurst S, Sun C. Mussel Adhesion: Finding the Tricks Worth Mimicking. The Journal of Adhesion. 2005;81:297–317. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Mussel-Inspired Surface Chemistry for Multifunctional Coatings. Science. 2007;318:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang SM, Rho J, Choi IS, Messersmith PB, Lee H. Norepinephrine: Material-Independent, Multifunctional Surface Modification Reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13224–13225. doi: 10.1021/ja905183k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu B, Edmondson S. Polydopamine-melanin initiators for Surface-initiated ATRP. Polymer. 2011;52:2141–2149. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matyjaszewski K, Xia J. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:2921–2990. doi: 10.1021/cr940534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmlin RE, Chen X, Chapman RG, Takayama S, Whitesides GM. Zwitterionic SAMs that Resist Nonspecific Adsorption of Protein from Aqueous Buffer. Langmuir. 2001;17:2841–2850. doi: 10.1021/la0015258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kane RS, Deschatelets P, Whitesides GM. Kosmotropes Form the Basis of Protein-Resistant Surfaces. Langmuir. 2003;19:2388–2391. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Chao T, Chen S, Jiang S. Superlow Fouling Sulfobetaine and Carboxybetaine Polymers on Glass Slides. Langmuir. 2006;22:10072–10077. doi: 10.1021/la062175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang W, Chen S, Cheng G, Vaisocherova H, Xue H, Li W, Zhang J, Jiang S. Film Thickness Dependence of Protein Adsorption from Blood Serum and Plasma onto Poly(sulfobetaine)-Grafted Surfaces. Langmuir. 2008;24:9211–9214. doi: 10.1021/la801487f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladd J, Zhang Z, Chen S, Hower JC, Jiang S. Zwitterionic Polymers Exhibiting High Resistance to Nonspecific Protein Adsorption from Human Serum and Plasma. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1357–1361. doi: 10.1021/bm701301s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez Emmenegger C, Brynda E, Riedel T, Sedlakova Z, Houska M, Alles AB. Interaction of Blood Plasma with Antifouling Surfaces. Langmuir. 2009;25:6328–6333. doi: 10.1021/la900083s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hower JC, Bernards MT, Chen S, Tsao HK, Sheng Y-J, Jiang S. Hydration of “Nonfouling” Functional Groups. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:197–201. doi: 10.1021/jp8065713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White A, Jiang S. Local and Bulk Hydration of Zwitterionic Glycine and its Analogues through Molecular Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2011;115:660–667. doi: 10.1021/jp1067654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statz AR, Barron AE, Messersmith PB. Protein, cell and bacterial fouling resistance of polypeptoid-modified surfaces: effect of side-chain chemistry. Soft Matter. 2007;4:131–139. doi: 10.1039/B711944E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng G, Li G, Xue H, Chen S, Bryers JD, Jiang S. Zwitterionic carboxybetaine polymer surfaces and their resistance to long-term biofilm formation. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5234–5240. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scofield JH. Hartree-Slater subshell photoionization cross-sections at 1254 and 1487 eV. Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 1976;8:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Chen S, Chang Y, Jiang S. Surface Grafted Sulfobetaine Polymers via Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization as Superlow Fouling Coatings. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110:10799–10804. doi: 10.1021/jp057266i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brault ND, Gao C, Xue H, Piliarik M, Homola J, Jiang S, Yu Q. Ultra-low fouling and functionalizable zwitterionic coatings grafted onto SiO2 via a biomimetic adhesive group for sensing and detection in complex media. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2010;25:2276–2282. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweryda-Krawiec B, Devaraj H, Jacob G, Hickman JJ. A New Interpretation of Serum Albumin Surface Passivation. Langmuir. 2004;20:2054–2056. doi: 10.1021/la034870g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Statz AR, Kuang J, Ren C, Barron AE, Szleifer I, Messersmith PB. Experimental and theoretical investigation of chain length and surface coverage on fouling of surface grafted polypeptoids. Biointerphases. 2009;4:FA22–FA32. doi: 10.1116/1.3115103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan X, Lin L, Messersmith PB. Cell Fouling Resistance of Polymer Brushes Grafted from Ti Substrates by Surface-Initiated Polymerization: Effect of Ethylene Glycol Side Chain Length. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2443–2448. doi: 10.1021/bm060276k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tugulu S, Klok H-A. Stability and Nonfouling Properties of Poly(poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate) Brushes under Cell Culture Conditions. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:906–912. doi: 10.1021/bm701293g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.