Abstract

Background

A recent research focus is a set of hypothesized adult-onset mental health disturbances possibly due to early-onset cannabis use (EOCU, onset <18 years). We seek to estimate the suspected EOCU-associated excess odds of experiencing an incident depression spell during adulthood, with comparisons to never cannabis smokers and those with delayed cannabis onset (i.e., not starting to smoke cannabis until adulthood).

Methods

The National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) assess non-institutionalized community-dwelling residents of the United States after probability sampling each year. In aggregate, the NSDUH analytical sample included 173,775 adult participants from survey years 2005–2009 (74–76% of designated respondents). Standardized computer-assisted interviews collected information on background determinants, age of first cannabis use, and depression spell onset. Logistic regression was used to estimate EOCU-depression spell associations in the form of odds ratios, with statistical adjustment for sex, age, race/ethnicity, years of cannabis involvement, tobacco cigarette onset, and alcohol onset.

Results

About 1 in 10 experienced a depression spell during adulthood, and both early-onset and adult-onset cannabis smokers had a modest excess odds of a depression spell compared to never cannabis smokers, even with covariate adjustment (OR = 1.7 & 1.8, respectively; both p<0.001). Estimates for early- and adult-onset cannabis smokers did not statistically differ from one another.

Limitations

Shared diathesis that might influence both EOCU and adult-onset depression spell is controlled no more than partially, as will be true until essentially all known early-life shared vulnerabilities are illuminated.

Conclusion

Cannabis smoking initiated at any age signals a modest increased risk of a spell of depression in adulthood, even when adjusted for suspected confounding variables studied here. Delaying cannabis onset until adulthood does not appear to diminish the cannabis-associated risk.

Keywords: cannabis, depression, early-onset, adult-onset, tobacco, alcohol

INTRODUCTION

Identification of the causes of depression and other mood disorders is a public health imperative. Global projections place unipolar major depression as the second leading cause of disability by 2020 (Murray & Lopez 1997). The economic costs associated with depression currently exceed $80 billion dollars annually in economically developed nations such as the United States (Greenberg et al. 2003). Depression is a complex disorder, with many possible component causes. One avenue of research has focused on substance use disorders, which have been found to be co-morbid with depression in clinical and epidemiological samples (Greenbaum et al. 1991; Brooner et al. 1997; Merikangas et al. 1998; Grant 1995). Inquiry into a connection between depression and specific psychoactive drug compounds have focused largely on tobacco (Glassman et al. 1990; Breslau et al. 1991; Kendler et al. 1993) and alcohol (Hasin & Grant 2002; Gilman & Abraham 2001; Boden & Fergusson 2011), with cannabis to a much lesser extent (see review by Degenhardt et al. 2003). Increasing occurrence of depression and suicide provoke public health concerns over the possible contribution of cannabis use to their etiology (Klerman & Weissman 1989; Wasserman et al. 2005; Compton et al. 2006).

The evidence for cannabis smoking as a potential toxin with respect to the occurrence of depression is mixed. Estimates of this association tend to be quite modest when the research has been designed to eliminate or constrain the possibility that depressed mood provokes initiation of cannabis smoking (L. Degenhardt et al. 2003; T. H. M. Moore et al. 2007). The resulting estimates now may be too modest to sustain a causal inference about cannabis toxicity (L. Degenhardt et al. 2003; Fergusson et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2002; Harder et al. 2008; de Graaf et al. 2010). An alternative mechanism of cannabis toxicity might be manifest in a casual chain or cascade model. That is, adolescent cannabis use might also function to influence later depression through indirect pathways that involve cannabis-induced lower educational attainment, greater likelihood of unemployment, associated financial strain, difficulties in establishing and maintaining close relationships, legal problems, more advanced illegal drug involvement, or other difficulties in assuming adult roles, which may increase the risk of depression (Kandel et al. 1986; Green & Ritter 2000; Marmorstein & Iacono 2011). Early-onset regular or problem cannabis use might modify this association (L. Degenhardt et al. 2003), yet few studies have tested this hypothesis in samples beyond the age of young adulthood. The aim of the present study is to clarify the cannabis-depression association with respect to early-onset cannabis smoking, looking across the adult lifespan of depression onset risk.

The distinction between early (during adolescence or before) and later (adult stage) onset cannabis smoking with respect to depression is of particular interest for several reasons. Adolescence is a period when age-specific incidence of starting to smoke cannabis and become dependent reaches peak values (F. Wagner & J. Anthony 2002; Stinson et al. 2006). By contrast, major depression (MD) typically occurs later in life, with the greatest risk observed after age 25 years (Kessler et al. 2005; Hasin et al. 2005; Kessler et al. 2007). Evidence from human and preclinical studies suggests that adolescence is a vulnerable period when exogenous agents such as cannabis might affect normal neurodevelopment (Rice & Barone 2000; Schneider 2008). Studies using the murine model support a role of endocannabinoids in mood regulation (M. Martin et al. 2002). Administration of cannabinoids during adolescence, but not in adulthood, seems to increase risk of later depression-like outcomes in these preclinical studies (Schneider & Koch 2003; Rubino et al. 2008; Bambico et al. 2010). From a public health perspective, one might argue that even a relatively modest cannabis-depression association might be large enough to lay claim to substantial burden of adult-onset depression, such as might be reduced by preventing or delaying onset of cannabis smoking.

Epidemiological findings are suggestive that early-onset cannabis smoking might increase risk of later depression. For example, in a longitudinal cohort followed from birth to young adulthood, Fergusson et al. (2002) found that weekly cannabis use was associated with a modest excess risk of depression in the same year. Another prospective study by Patton and colleagues (2002) reported a two-fold increase of depression by 20–21 years in regular, early-onset cannabis smoking females (but not males). Other studies report similar findings, but there are negative studies as well (Green & Ritter 2000; D. W. Brook et al. 2002; Hayatbakhsh et al. 2007; Groth & Morrison-Beedy 2010; Pahl et al. 2010; Fergusson & Horwood 1997; M. T. Lynskey et al. 2004; Windle & Wiesner 2004; Pedersen 2008; Degenhardt et al. 2010; Griffith-Lendering et al. 2011).

The present study seeks to build upon this evidence by first estimating the degree to which the onset of a newly sustained spell of depression with allied features (herein after referred to as a ‘depression spell’) measured across a broad span of adult years might be dependent upon whether cannabis smoking has been initiated before adulthood (i.e., ‘early-onset’, or age 17 years or younger), within the context of a general conceptual model. Secondly, we wish to evaluate whether the estimate for the association between early-onset cannabis use and depression spell might differ for cannabis smokers who start in adulthood (age 18 years or older).

To clarify our concept of a depression spell, we note the definition for a spell differs from the diagnostic criteria specified for major depressive episode (MDE) as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV). In specific, the assessment of a spell is made without diagnostic hierarchies or exclusions due to psychotic disorders, drug intoxication, bereavement, etc. The spell is extended over a span of more than one week, but the spell’s allied clinical features such as psychomotor retardation or pathological guilt might be relatively transient, and too short in duration to fulfill the MDE criteria.

One of our concerns in this research is that early-onset cannabis smoking might be little more than a marker for longer cumulative cannabis exposure (L. Degenhardt et al. 2003). As such, we have included in our models a measure of the elapsed time of cannabis involvement, risking model mis-specification as explained below.

In addition, with respect to our conceptual model, we recognize that the occurrence of depression spells and cannabis use varies across population subgroups defined by characteristics such as sex, age, and race/ethnicity (Kessler et al. 2005; Johnston et al. 2006). We also note that the EOCU-depression association under study might be traced to imbalances in tobacco cigarette smoking or alcohol use (Breslau et al. 1993; Gilman & Abraham 2001). For these reasons, we have included these variables in our conceptual models and analyses.

METHODS

Study Sample and Data Collection

The US National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) are annual cross-sectional surveys, with large multi-stage area probability samples designed to yield nationally representative samples of non-institutionalized civilian residents aged 12 years or older. Within each year’s multi-stage probability sample of dwelling units (DU) within the target population. eligible designated respondents (DRs) are sampled and recruited, with a sampling frame that includes homeless shelters and other non-institutionalized group quarters. Participation levels are gauged in relation to an overall weighted screening response rate (to determine DU eligibility and roster DRs) and a weighted interview response rate. Between 2005 and 2009, these response rates ranged from 89–91% and 74–76%, respectively. Each survey year generates about 55,000 observations in public use datasets made available for non-governmental research, with an effective total sample size of 278,130 for the surveys conducted in these years.

Highly standardized and audio-enhanced computerized laptop self-assessment methods have been used in the NSDUH to enhance response validity of data collected within or near the respondent’s home, with deliberate attempts to optimize privacy and confidentiality of responses about illegal drug use and sensitive behaviors. An interview/reinterview reliability study conducted in 2006 among 3,136 individuals found a high degree of agreement on drug use variables (kappa > 0.8) and moderate to substantial agreement on depression variables (kappa of 0.4 to 0.8, depending upon the variables under study). For these reliability studies, individuals were interviewed on two occasions, generally 5 to 15 days apart, which might have dampened the depression kappa values due to state changes over a span of that duration (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2010).

The study protocols for data gathering and analysis were reviewed and approved by the cognizant institutional review boards for protection of human subjects in research. Details on NSDUH methods can be found online: http://oas.samhsa.gov/redesigningNHSDA.pdf (last accessed 19 September 2011).

For this study’s analyses, there were some study exclusions based on age at the time of assessment as well as pre-adult onsets of depression spells. That is, 12–17 year olds were not studied because they had not yet reached the years of adult at-risk experience. In addition, anyone who had experienced a depression spell before adulthood (age 18 years). As for the exclusions, the majority consisted of 90,266 minors aged 12–17 years at the time of the interview (i.e., had not yet entered adulthood), as well as 11,229 who had experienced a depression spell prior to 18 years of age. An additional 2,265 respondents had to be excluded due to missing data on actual depression spell age of onset. Finally, 595 of depression spell cases were dropped from the analysis because the cannabis age of onset occurred after their age of depression spell onset, in a violation of an assumption of EOCU must precede depression onset if it is to regarded as a viable cause of the first onset of a depression spell in the adult lifetime. The final analytical sample consisted of 173,775 individuals.

The Key Response Variable in This Study: Adult-Onset Depression Spell

The key response variable in this study was the first occurrence of a depression spell in adulthood (≥18 years of age). A depression spell was operationally defined as experiencing feelings of sadness, discouragement, or loss of interest lasting most of the day, nearly every day, for a period of two weeks or longer and having at least one of the following allied clinical features: problems with sleep, appetite, energy, the ability to concentrate or remember, or feelings of low self worth (not necessarily lasting two weeks or more). Depression spell status was measured via a set of standardized questions administered as part of an MDE assessment of all DSM-IV-specified clinical features of MDE. One item assessed lifetime experience of low mood: “Have you ever in your life had a period of time lasting several days or longer when most of the day you [felt sad, empty or depressed / were very discouraged about how things were going in your life / lost interest in most things you usually enjoy like work, hobbies, and personal relationships]?” Two additional items assessed the age at which the respondent first experienced a two week depression spell and whether any of the allied clinical features covered as part of the MDE assessment had occurred during the same two week period, even though they might not have lasted for two weeks.

A reasonable question is why this study does not estimate the association linking EOCU with risk of Major Depressive Episode. The rationale has been explained by Chen et al. (2002), who noted that the DSM criteria for MDE require exclusion of depression syndromes that are attributable to drug use or other known toxic exposures. Diagnostic assessments such as the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule implement this diagnostic hierarchy at the level of each clinical feature, asking the drug user whether the clinical feature only occurred as a result of drug use. The NSDUH assessment does not include this methodological refinement, such that identified MDE cases actually might be caused by cannabis smoking. Focus on the depression spell finesses this methodological problem because there is no DSM hierarchy or diagnostic exclusion criterion for drug-induced depression spells. The occurrence of depression spells is free to vary and might be influenced by prior or concurrent cannabis smoking without influence from a pre-specified diagnostic hierarchy.

Onset of Cannabis Use and Elapsed Time of Cannabis Involvement

Cannabis onset also was assessed via a series standardized questions. First, the respondent was asked, “Have you ever, even once, used marijuana or hashish?” When respondents answered ‘No’, they were categorized as “Never” users. When respondents answered ‘Yes’, then age of onset was assessed via a separate standardized item, “How old were you the first time you used marijuana or hashish?” Accordingly, cannabis-using respondents were categorized into either “Early (<18 Years)” or “Adult (≥18 Years)” cannabis onset. All other respondents were carried along in the analysis in a category of ‘missing” values for the cannabis onset age variable.

The elapsed time of cannabis involvement was conceptualized as the number of years between the age of onset of cannabis use and the age of last use. Age of last cannabis use was measured as follows: “How old were you the last time you used marijuana or hashish?” Elapsed time of cannabis involvement was estimated by subtracting the age of last use from age of first use. Respondents were then categorized, prior to analyses of the depression spell data, into the following levels of elapsed time of cannabis involvement: “Never”, “< 1 year”, “1–10 years”, and “11 or more years,” which optimized cell sizes for each of these categories. Respondents missing on either age of first or last cannabis use were categorized as “missing” with respect to the elapsed time variable.

Other Drug Use Variables and Background Characteristics

Tobacco cigarette onset and alcohol drinking onset variables were measured in a similar fashion, via standardized items, with categorization schemes the same as those just described. Standardized items also assessed background characteristics such as sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Other background variables in the conceptual model included some variables that actually might have been influenced by either EOCU or by occurrence of a depression spell, including marital status, number of times married, total family income, population density, other illegal drug use besides cannabis, educational attainment, current employment status, ever been arrested, and lifetime occurrence of anxiety disorder. Nonetheless, statistical adjustment for these variables makes it possible to look into a suspected EOCU-depression association might be statistically independent and robust, even when these correlates (and potential consequences) of drug use or depression are held constant via regression modeling.

Data Analysis

The plan for data analysis was organized in relation to a now-standard “explore, analyze, explore” cycle, in which the first exploratory steps involved histogram plots and other exploratory data analyses to shed light on the underlying distributions of the response variable and each covariate of interest. In the initial analysis step, we performed a series of logistic regressions between our depression spell outcome and cannabis onset, elapsed time of cannabis involvement, tobacco cigarette onset, and alcohol onset to produce unadjusted odds ratio (OR) estimates. All analyses took into account sampling weights and the complex sample structure for variance estimation purposes. In a subsequent analytical step, the statistical approach involved constructing a multivariable model that included all previously listed covariates plus adjustment for sex, age, race/ethnicity, and survey year. Our final exploratory analytical step consisted of probing the degree to which the early-onset cannabis estimate varied when introducing other covariates into the model one at a time, and then all at once. In this work, we are stressing precision of the study estimates with a focus on 95% confidence intervals and with p-values presented as an aid to interpretation.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the sample in terms of selected background characteristics by depression spell cases and non-cases. About 1 in 10 adults in the sample had experienced a depression spell at age 18 or in subsequent adult years. Cases were more likely to be female, white, and older than 25 years of age, have a post-high school education, and divorced or separated.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by depression spell status (n=173,775)

| Characteristic | Depression spell ≥ 18 years

|

Never experienced a depression spell

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (wt) | n | % (wt) | |

| Total | 16,108 | 10% | 157,667 | 90% |

| Age Group | ||||

| 18–25 | 5,654 | 7% | 77,988 | 93% |

| 26–34 | 2,892 | 11% | 23,133 | 89% |

| 35–49 | 4,978 | 12% | 32,806 | 88% |

| 50 or older | 2,584 | 10% | 23,740 | 90% |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 5,536 | 8% | 77,190 | 92% |

| Female | 10,572 | 13% | 80,477 | 87% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 11,302 | 12% | 100,370 | 88% |

| Black | 1,643 | 8% | 19,841 | 92% |

| Hispanic | 1,995 | 8% | 24,731 | 92% |

| Asian | 390 | 5% | 6,035 | 95% |

| All Othersa | 778 | 11% | 6,690 | 89% |

| Highest Level of Education | ||||

| Less than High School | 2,038 | 8% | 28,465 | 92% |

| High School Graduate | 4,736 | 9% | 52,954 | 91% |

| Some College | 5,315 | 12% | 44,281 | 88% |

| College Graduate | 4,019 | 12% | 31,967 | 88% |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Full-time | 8,505 | 10% | 83,690 | 90% |

| Part-time | 2,773 | 11% | 28,867 | 89% |

| Unemployed | 1,042 | 12% | 10,267 | 88% |

| Otherb | 3,788 | 10% | 34,843 | 90% |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 6,252 | 9% | 60,275 | 91% |

| Widowed | 499 | 10% | 3,937 | 90% |

| Divorced/Separated | 2,783 | 17% | 12,863 | 83% |

| Never married | 6,574 | 9% | 80,592 | 91% |

wt, weighted percent

Includes Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, Native Hawaiians, Other Pacific Islanders, and those with more than one race/ethnicity

Included, but not in the labor force

From Table 2, the proportion of cases who had smoked cannabis before age 18 (14%) was identical to those who had started later (14%). Depression spells were over-represented among cannabis users with the longest elapsed time of cannabis involvement (11 years or longer, 19%). A greater proportion of depression spells occurred among early-onset tobacco cigarette (12%) and alcohol (12%) users.

Table 2.

Frequency, weighted proportions, and results of logistic regression analysis of depression spell status with cannabis onset exposure status, years of cannabis involvement, and other substance onset variables. US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005–2009 (n=173,775).

| Drug Exposure | Depression spell ≥ 18 years

|

Never experienced a depression spell

|

Model 1 - Unadjusted logistic regression estimatesa |

Model 2 - Adjusted logistic regression estimatesb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (wt) | n | % (wt) | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | OR | (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Cannabis Onset | ||||||||||

| Never | 6,185 | 7% | 84,113 | 93% | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Early (< 18 years) | 6,454 | 14% | 48,437 | 86% | 2.2 | (2.0, 2.3) | <0.001 | 1.7 | (1.5, 1.9) | <0.001 |

| Adult (≥18 years) | 3,439 | 14% | 24,650 | 86% | 2.0 | (1.9, 2.1) | <0.001 | 1.8 | (1.6, 1.9) | <0.001 |

| Missing Datac | 30 | 7% | 467 | 93% | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.5) | 0.986 | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.7) | 0.745 |

| Years of Cannabis Involvementd | ||||||||||

| 0 years (Never) | 6,185 | 7% | 84,113 | 93% | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| < 1 year | 1,502 | 12% | 13,186 | 88% | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.9) | <0.001 | 0.8 | (0.7, 0.9) | 0.002 |

| 1–10 years | 4,217 | 13% | 31,746 | 87% | 2.0 | (1.9, 2.1) | <0.001 | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.1) | 0.498 |

| 11 or more years | 2,153 | 19% | 9,164 | 82% | 2.9 | (2.7, 3.2) | <0.001 | 1.4 | (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 |

| Missing Datac | 2,051 | 12% | 19,458 | 88% | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.9) | <0.001 | NA | ||

| Tobacco Cigarette Onset | ||||||||||

| Never | 3,510 | 7% | 51,435 | 93% | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Early (< 18 years) | 9,697 | 12% | 79,073 | 88% | 1.9 | (1.8, 2.1) | <0.001 | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 |

| Adult (≥18 years) | 2,848 | 10% | 26,342 | 90% | 1.5 | (1.3, 1.6) | <0.001 | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.2) | 0.104 |

| Missing Datac | 53 | 6% | 817 | 94% | 0.9 | (0.6, 1.4) | 0.689 | 1.0 | (0.6, 1.5) | 0.942 |

| Alcohol Onset | ||||||||||

| Never | 945 | 5% | 21,178 | 95% | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Early (< 18 years) | 10,300 | 12% | 86,231 | 88% | 2.9 | (2.6, 3.3) | <0.001 | 2.0 | (1.7, 2.3) | <0.001 |

| Adult (≥18 years) | 4,790 | 9% | 48,943 | 91% | 2.1 | (1.8, 2.3) | <0.001 | 1.7 | (1.5, 1.9) | <0.001 |

| Missing Datac | 73 | 6% | 1,315 | 94% | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.8) | 0.226 | 1.1 | (0.7, 1.5) | 0.737 |

wt, weighted percent; OR, Odds Ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval; NA, estimates could not be produced

Separate logistic regression analysis between depression spell outcome and each individual drug exposure variable.

Model 2 adjusted for each variable in Table 2 plus sex, age, race/ethnicity, and survey year.

Missing data included respondents who answered ‘don’t know’, ‘refused’, left item blank, or otherwise had bad data.

Years of cannabis involvement defined as [Age of last cannabis use] - [Age of first cannabis use] for respondents who had ever used cannabis.

Results from the logistic regression analysis prior to covariate adjustment showed a twofold excess odds of a later depression spell for early-onset cannabis smokers as compared to never cannabis smokers (estimated odds ratio, OR = 2.2; Table 2, Model 1). While the estimate for adult-onset cannabis smokers was nearly the same (OR = 2.0), a statistical test of differences revealed these two estimates to be distinct (p=0.029; not shown in table). When the estimates were adjusted for elapsed time of cannabis involvement, tobacco onset, alcohol onset, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and survey year, there was a attenuation towards null (Early-onset: OR = 1.7; Adult-onset: OR = 1.8), but both estimates remained statistically significant at p<0.001. In contrast to the estimates from models without covariate adjustments, there was no statistically significant difference between the odds ratio estimates for early-onset and adult-onset cannabis users (p=0.286; data not shown in table).

From Table 2, one can also see estimates for the unadjusted and covariate-adjusted depression spell-related odds associated with tobacco cigarette and alcohol onset. Adult-onset tobacco cigarette smoking was not associated with depression spells after adjustment for covariates in the model (unadjusted OR = 1.5; p<0.001; adjusted OR = 1.1; p=0.104). Nevertheless, there was a very small excess odds that linked adult-onset occurrence of a depression spell with early-onset tobacco smoking (adjusted OR = 1.2; p<0.001), independent of the EOCU-depression association. Both early- and adult-onset alcohol drinking were noteworthy covariates in the covariate-adjusted model (OR = 2.0 and 1.7, respectively; both p<0.001). Post-estimation analysis revealed that the difference between these two odds ratio estimates was statistically significant at p<0.001 (data not shown in table).

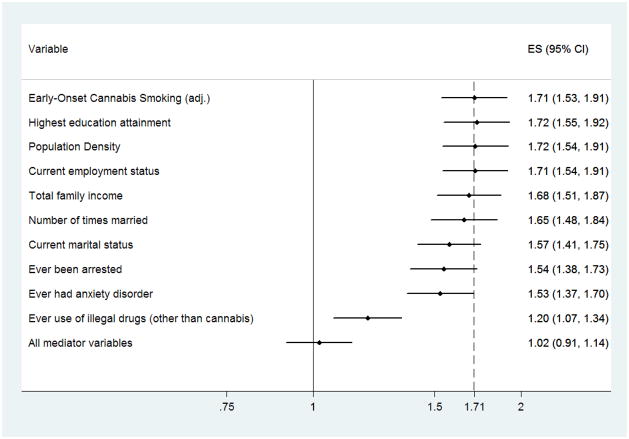

In the first set of formal post-estimation exploratory analyses, addition of covariate terms to control for ‘ever had an anxiety disorder’ or ‘use of other illegal drugs other than cannabis’ yielded a potentially noteworthy attenuation of the OR point estimate for the EOCU-depression spell association (Figure 1). Addition of a covariate term for use of internationally regulated drugs other than cannabis yielded even more attenuation of the OR estimate (a shift of roughly 30% of the point estimate in the direction of the null). Introduction of covariates for other characteristics, many of which might be consequences of cannabis smoking (e.g., educational attainment), did little to affect the estimated association linking EOCU with later adult-onset of a depression spell. Nonetheless, when all such variables were included in the model at once, the estimated odds of an adult-onset depression spell for early-onset cannabis users did not differ from the null (OR = 1.02; 95% CI: 0.91, 1.14; p=0.715). The corresponding estimate for the association as might link adult-onset cannabis smoking with adult-onset depression spell remained statistically significant at p=0.005, but was much attenuated (i.e., OR = 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1, 1.3; data not shown in figure), and cannot actually be interpreted as a potentially causal association because the covariate values actually might have post-dated either onset of cannabis smoking or onset of the adult-onset depression spell (i.e., these variables might have values that are consequences of EOCU or depression spells, and they might have no causal significance whatsoever).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the variation in the EOCU-depression spell estimate when additional covariates are introduced into the multivariable logistic regression model

In the second set of exploratory analyses (Table 3), onset of cannabis smoking before age 15 or at 18 years or older was found to be associated with occurrence of later adult-onset depression spells, even with covariate adjustment, in a comparison with never users of cannabis as a reference or comparison subgroup (OR = 1.9; OR = 1.7, respectively; Table 3). In these analyses we probed for possibly evidence that a different age threshold for EOCU might have produced stronger associations between EOCU and occurrence of the depression spell. We found no evidence to prompt us to report quantitative estimates from this set of exploratory analyses (contrast between ≤15 years and 18 years or older p-value = 0.190; data not shown in a table).

Table 3.

Exploratory adjusted logistic regression analysis of association between depression spell and fine-grained cannabis onset exposure

| Model 3a - Adjusted logistic regression (fine grained onset)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Cannabis Onset | |||

| Never | 1.0 | ||

| ≤ 15 years | 1.9 | (1.6, 2.1) | <0.001 |

| 15 years | 1.7 | (1.5, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| 16 years | 1.6 | (1.4, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| 17 years | 1.6 | (1.4, 1.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 18 years | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.9) | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio

Model adjusted for elapsed time of cannabis involvement, tobacco cigarette onset, alcohol onset, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and survey year.

DISCUSSION

Our primary research aim was to estimate the degree to which early-onset cannabis smoking initiated prior to age 18 years might signal an increased risk of a later adult-onset incident depression spell. We found no more than a modest excess odds for this relationship in a comparison with individuals who had never smoked cannabis. This association remained statistically robust after covariate adjustment for elapsed time of cannabis involvement, onset of tobacco cigarettes and alcohol, sex, age, and race/ethnicity, consistent with prior studies predicting a modest association between various forms of adolescent cannabis use and later depression in adolescence or young adulthood (Green & Ritter 2000; D. W. Brook et al. 2002; Fergusson et al. 2002; G.C. Patton et al. 2002; Rey et al. 2002; Hayatbakhsh et al. 2007; Groth & Morrison-Beedy 2010; Pahl et al. 2010). Our study’s results add to the literature on the association between cannabis and depression by extending the timeline to include the first occurrence of a sustained spell of depression in older age groups. This refinement was made possible via a constraint on the temporal sequencing of first cannabis use and depression spell, made possible by using age-of-onset data. However, for completeness, we must note several studies with null results, in which original unadjusted associations were rendered null once potential confounders were taken into account, much as the associations under study here were much-attenuated with statistical adjustments for covariates of interest (e.g., see Fergusson & Horwood 1997; M. T. Lynskey et al. 2004; Windle & Wiesner 2004; Pedersen 2008; Louisa Degenhardt et al. 2010; de Graaf et al. 2010; Griffith-Lendering et al. 2011).

Readers may interpret the overall population estimate as too modest to sustain a causal inference due to uncontrolled sources of potential confounding, such as a diathesis that might determine both EOCU and adult-onset depression spells. For example, de Graaf and colleagues (2010) suggested that early behavioral dysregulation or conduct problems might be one such indication of a shared diathesis. If controlled, these now-omitted background characteristics might well render the association null, as in de Graaf et al. (2010). Whereas the present study included no measures of early behavioral or conduct problems, Greenland and O’Rouke (2008) provide an approach that can be used to gauge whether (and by how much) an association might shift toward the null if an unmeasured covariate had been controlled. Their method is based upon the ratio of adjusted and unadjusted estimates as derived from prior research. To illustrate, according to estimates reported by de Graaf et al. (2010), the ratio of adjusted to unadjusted OR estimates is 0.9. As forecast by the Greenland-O’Rourke method, multiplication of 0.9 times the present study’s point estimate of 1.7 yields an odds ratio estimate of 1.5 (i.e., closer to the null). Accordingly, this study’s conclusion continues to be that the link from early-onset cannabis smoking to later adult-onset of a depression spell is quite modest (but is non-null).

Our secondary research question was whether the estimated associations with depression spell might be different when studied in association with adult-onset cannabis smoking. In this study’s estimates, we found little difference between the early-onset and adult-onset subgroups of cannabis smoking onset with respect to occurrence of adult-onset depression spells in models with covariate adjustment for potential confounders and background characteristics. One might expect that the delay of cannabis onset until adulthood might have a diminished effect on the incidence of depression spells, in congruence with theories of either a direct influence of exogenous cannabinoids on the maturing adolescent brain (Rice & Barone 2000; Schneider 2008), or an indirect influence through difficulty in assuming adult roles that lead to depression (Kandel et al. 1986; Green & Ritter 2000; Marmorstein & Iacono 2011). Our findings cannot be said to support these theoretical formulation of cannabis-depression associations. In addition, one might also expect the effect of EOCU to be greater and more pronounced when cannabis smoking has started very very early in late childhood or early adolescence, as compared to associations found when cannabis smoking has started in later adolescence. However, when we separated early-onset cannabis smoking into year-by-year age categories, we found no strong support for any age-related gradient in the strength of association after statistical adjustment. As such, early-onset cannabis smoking might merely be a marker for more regular, chronic use in adulthood. For example, Georgiades and Boyle (2007) found that cannabis use in adolescence only (but not in adulthood) had little association with depression, but that occurrence of depression was associated with cannabis use in adolescence and continued into adulthood, as well as with adult-onset cannabis smoking without adolescent use of cannabis.

The effect of early-onset cannabis use on later depression spells, if any, might be mediated through the influence of adolescent cannabis use on psychosocial factors associated with depression. Most of the variables we considered individually - educational attainment, employment status, total family income, marital status, number of times married, ever been arrested, population density - had little apparent effect on the early-onset cannabis-associated odds of depression spells. Covariate terms for ‘ever had an anxiety disorder’ and ‘ever using other illegal drugs other than cannabis’ produced noteworthy but not full attenuation of the originally observed EOCU-depression spell associations. Only when all variables were considered together was the estimate found to null, with never smokers as a comparison subgroup. Green and Ritter (2000) reported a similar finding after including educational attainment, employment status, marital status, and other drug use (alcohol and tobacco). However, in a recent investigation, Marmorstean and Iacono (2011) concluded that the effect of cannabis use disorder in adolescence on depression was not more than partially mediated by adverse psychosocial consequences such as educational failure, unemployment, and criminal behavior. Accordingly, it may be noted that our post-estimation explore step yielded results that are generally consistent the theory that the association between earlier cannabis use and later depression may be through intermediate psychosocial factors, which may increase the risk of depression (Kandel et al. 1986). Of course, we should note at least one limitation to this approach: since these variables were assessed as of the time of the interview, we cannot be certain these variables lie within the causal chain – e.g., they could be a result of depressed mood, rather than a cause.

Early-onset tobacco or alcohol use was also associated with an excess odds of a later depression spell. The strength of the association was very modest for early tobacco cigarette smoking, but about two-fold for early alcohol drinking. Adjustment for cannabis and alcohol use, in theory, might attenuate estimates of the effect of early-onset tobacco cigarette use, which typically has an earlier onset than other drugs (L. Degenhardt et al. 2008). A related rationale might be used to explain the finding that adult-onset tobacco cigarette smoking was not associated with depression spells. For alcohol drinking, both early- and adult-onset drinking were positively associated with depression spells, but the odds ratio based on early-onset drinkers were slightly greater and statistically different than the odds ratio estimates based on adult-onset drinkers. While speculative, the pattern of findings might prompt a suggestion that it could be possible to attempt prevention or delay of the onset of alcohol drinking, which in turn might have an impact on occurrence of later mood disturbances. However, our aim was not to test this relationship, and we should point out that our conceptual model did not account for lifetime cumulative exposure of tobacco or alcohol, such as with elapsed time of cannabis involvement, which might explain these findings. Recent reviews by Chaiton et al. (2009) and Boden and Fergusson (2011) conclude in favor of causal relationships that link tobacco smoking or alcohol drinking, with physical health, and also with depression.

This research should be viewed in light of several additional limitations, as noted below. First, the NSDUH collects little information on the childhood experiences of adult respondents at the time of interview. As a consequence, some potential confounders of the cannabis-depression association, such as a history of childhood conduct problems, early family dysfunction, or other mental disorders likely to have their onset in childhood/adolescence were not measured and therefore are omitted variables (L. Degenhardt et al. 2003). As illustrated using the Greenland-O’Rourke method, covariate adjustment most likely implies attenuated and perhaps null cannabis-depression associations due to the omission of these potentially confounding variables in the NSDUH measurement plan. Second, difficulties in recall or reporting of the age of onset of cannabis use or depression spell sometimes can occur, although in this sample there often were large differences in the age-of-onset of cannabis smoking in relation to age-of-onset of depression spells, which implies that roughly accurate age-of-onset values should suffice in this context. Third, the link from cannabis to depression might unfold within a matter of weeks or months after adolescent onset of cannabis smoking. If so, a research design with week-to-week or month-to-month time sequence granularity would be required to disclose any palpable association under these circumstances, and the case-crossover design might be needed (e.g., see O’Brien et al. 2005). This specific limitation does not undermine the value of the study estimates just reported, which are based on a prevailing view that early-onset cannabis use might be a signal of later incident depression spells occurring well after the interval of cannabis intoxication (e.g., Chen et al. 2002).

Some strengths of this research include having large sample sizes that yield statistically precise estimates even when modest-level associations are observed, the strengths of a nationally representative sample that helps to promote the external validity of these results, as well as standardized computer-assisted assessment methods to maximize validity and reliability of the study measurements. That is, computer-assisted self-interviewing methods may have helped ensure more honest, more complete, and perhaps more accurate responses to questions on sensitive topics such as drug use and mood disturbances such as depression spells. These are important strengths in a cross-sectional survey that is unburdened by the uncertainties that come with sample attrition during longitudinal follow-up studies on relationships of this type, which otherwise might be said to yield important evidence on a cannabis-depression association of public health significance.

To conclude with an honest appraisal of the present findings, the accumulated evidence, and their implications, we must draw attention to a prominent assumption of all current observational research on the suspected hazards associated with early-onset drug use, including cannabis smoking. The rest of this concluding statement is offered with a spirit of mind prompted by Professor C.F. Manski’s description of a general problem in human behavioral and social science research of an observational character. Namely, Manski has noted that in these research areas we often fail “… to face up to the difficulty of [the] enterprise. Researchers sometimes do not recognize that the interpretation of data requires assumptions. Researchers sometimes understand the logic of scientific inference but ignore it when reporting their own work. The scientific community rewards those who produce strong novel findings. The public, impatient for solutions to its pressing concerns, rewards those who offer simple analyses leading to unequivocal policy recommendations. These incentives make it tempting for researchers to maintain assumptions far stronger than they can persuasively defend, in order to draw strong conclusions” (Manski 1999).

Accordingly, we close by reminding our readers of a crucial assumption, if we are to evaluate the current evidence and judge that the prevalence of adult-onset depression spells might be reduced by preventing or delaying onset of cannabis smoking. Namely, as outlined elsewhere (O’Brien et al., in press; Anthony, submitted), the crucial assumption is the ‘no omitted variables’ assumption in relation to our model specifications. Here, we must assume that there is no set of background variables, lurking behind the scenes, either unknown or unmeasured or ineptly measured, that might be functioning as a common vulnerability trait, accounting for both (a) an occasion of adolescent-onset cannabis smoking before age 18 years, and (b) an adult-onset depression spell after the 18th birthday. If there is an omitted variable, such as a gene that manifests its influence in the form of a simple pleiotropism, as might be the case with a genetic mutation that gives rise to an excess risk of both early-onset cannabis smoking and a later-onset depression spell, then it might be controlled in a behavioral genetics research design (e.g., with monozygotic twins). Nevertheless, if one suspects epigenesis or other forms of gene-environment interaction as a common substrate, then a subject-as-own-control (SAOC) type design would be required, and regrettably the primary SAOC design for large sample research is the epidemiologic case-crossover design -- which has little utility when there is a long induction interval from suspected causal exposure to later excess risk (O’Brien et al., in press). Accordingly, in the next step toward confirmation of the suspected cannabis-depression causal association, it might be best to turn attention toward randomized prevention trial evidence, where an early drug use prevention program has prevented or delayed the adolescent-onset of cannabis smoking. With a follow-up of adolescent prevention program participants into the adult years, there might be evidence of a linked reduction in the form of later reduced risk of the depression spell among those who responded well to the drug prevention program. A less compelling alternative design might involve a prospective follow-up of adolescent-onset cannabis smokers, stratified by whether initial cannabis smoking persisted and for how long it persisted, with an expectation that there might be reduced risk of the depression spell among adolescents who tried cannabis just once or twice and never again, or possibly a gradient of increasing risk across strata defined by length of persistent cannabis smoking in adolescence. Here again, the ‘no omitted variables’ assumption would surface, in that the earlier vulnerability to reinforcing effects of cannabis smoking (with subsequent persistence of cannabis use) might also be a cause or marker of later vulnerability for a depression spell. It is for this reason that we judge the follow-up of adolescent participants in randomized prevention experiments to be a more compelling next step in this line of research.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

The authors wish to acknowledge the project’s funding sources which include the National Institute on Drug Abuse awards K05DA015799, T32DA021129, and MSU research funds from the Office of the Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies.

The authors wish to thank Dr. David Barondess, John Troost, and the other NIDA-supported T32/D43 trainees from Michigan State University for their conceptual guidance and copy editing support. We also are grateful to the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies, which administers the NSDUH and arranges for timely release of the NSDUH public use datasets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors wish to thank Dr. David Barondess, John Troost, and the other NIDA-supported T32/D43 trainees from Michigan State University for their conceptual guidance and copy editing support. We also are grateful to the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies, which administers the NSDUH and arranges for timely release of the NSDUH public use datasets. The authors wish to acknowledge the project’s funding sources which include the National Institute on Drug Abuse awards K05DA015799, T32DA021129, and MSU research funds from the Office of the Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributors

The first author (B. Fairman) wrote the first draft of the manuscript, managed the literature searches, and conducted the analyses. The second author (J. Anthony) helped interpret the results of the study, provided guidance on analysis issues, aided in the interpretation of the study’s conclusion with reference to prior literature, and made substantial contributions to the final draft text. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bambico FR, et al. Chronic exposure to cannabinoids during adolescence but not during adulthood impairs emotional behaviour and monoaminergic neurotransmission. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;37(3):641–655. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106(5):906–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence and major depression: new evidence from a prospective investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(1):31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48(12):1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, et al. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooner RK, et al. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Archives of General psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130077015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton MO, et al. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Marijuana use and the risk of Major Depressive Episode Epidemiological evidence from the United States National Comorbidity Survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37(5):199–206. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, et al. Changes in the prevalence of major depression and comorbid substance use disorders in the United States between 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2141. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, et al. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2008;5(7):1053–1067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98(11):1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, Louisa, et al. Outcomes of occasional cannabis use in adolescence: 10-year follow-up study in Victoria, Australia. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 2010;196(4):290–295. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early onset cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in young adults. Addiction. 1997;92(3):279–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression* 1. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, et al. Smoking, Smoking Cessation, and Major Depression. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(12):1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R, et al. Early cannabis use and estimated risk of later onset of depression spells. Epidemiological evidence from the population-based WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;172(2):149–159. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey of adults. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7(4):481–497. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BE, Ritter C. Marijuana use and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(1):40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, et al. Substance abuse prevalence and comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders among adolescents with severe emotional disturbances. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):575–583. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64(12):1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, O’Rourke K. Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Meta-Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith-Lendering MFH, et al. Cannabis use and development of externalizing and internalizing behaviour problems in early adolescence: A TRAILS study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;116(1–3):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth SW, Morrison-Beedy D. Smoking, Substance Use, and Mental Health Correlates in Urban Adolescent Girls. Journal of Community Health. 2010;36(4):552–558. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder VS, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Adolescent cannabis problems and young adult depression: male-female stratified propensity score analyses. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(6):592. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF. Major depression in 6050 former drinkers: association with past alcohol dependence. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59(9):794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, et al. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, et al. Cannabis and anxiety and depression in young adults: a large prospective study. Journal of Amer Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(3):408. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802dc54d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2005. Volume I. Secondary School Students. National Institutes of Health. 2006:715. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, et al. The Consequences in Young Adulthood of Adolescent Drug Involvement - an Overview. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43(8):746–754. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, et al. Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(1):36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Increasing Rates of Depression. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261(15):2229–2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, et al. Major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt in twins discordant for cannabis dependence and early-onset cannabis use. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1026. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manski CF. Identification problems in the social sciences. Harvard Univ Pr; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG. Explaining associations between cannabis use disorders in adolescence and later major depression: A test of the psychosocial failure model. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(7):773–776. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, et al. Involvement of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in emotional behaviour. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159(4):379–387. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders:: Results of the international consortium in psychiatric epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):893–907. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore THM, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MS, Wu LT, Anthony JC. Cocaine use and the occurrence of panic attacks in the community: a case-crossover approach. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40(3):285–297. doi: 10.1081/ja-200049236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Brook JS, Koppel J. Trajectories of marijuana use and psychological adjustment among urban African American and Puerto Rican women. Psychological Medicine. 2010;41(8):1775–1783. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, et al. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2002;325(7374):1195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W. Does cannabis use lead to depression and suicidal behaviours? A population-based longitudinal study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118(5):395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, et al. Mental health of teenagers who use cannabis - Results of an Australian survey. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:216–221. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D, Barone S. Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: Evidence from humans and animal models. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2000;108:511–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, et al. Chronic 9-tetrahydrocannabinol during adolescence provokes sex-dependent changes in the emotional profile in adult rats: behavioral and biochemical correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(11):2760–2771. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M. Puberty as a highly vulnerable developmental period for the consequences of cannabis exposure. Addiction biology. 2008;13(2):253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Koch M. Chronic pubertal, but not adult chronic cannabinoid treatment impairs sensorimotor gating, recognition memory, and the performance in a progressive ratio task in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(10):1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, et al. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(10):1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner F, Anthony J. From first drug use to drug dependence: Developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. NEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY. 2002;26(4):479–488. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASSERMAN D, CHENG Q, JIANG G-X. Global suicide rates among young people aged 15–19. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(2):114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Wiesner M. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: predictors and outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(4):1007–1027. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]