Abstract

It has been demonstrated elsewhere that a high concentration of an antigen within the nucleolus may prevent its proper recognition by specific antibodies. In this study, the authors found that a short proteinase treatment allowed for the detection of antigens in the nucleoli. The described approach is compatible with the simultaneous observation of proteins fused to fluorescent tags and with preembedding electron microscopy. It appears that the described method can be useful in situations when the proper recognition of antigens by specific antibodies is disturbed by a high density of cellular structures or a high concentration of antigens inside these structures.

Keywords: immunocytochemistry, antibody, nucleolus

The nucleolus is the most prominent structure within the eukaryotic nucleus and is known for its role in ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcription, processing, and the subsequent assembly of processed rRNA with ribosomal proteins to form preribosomal subunits (Cmarko et al. 2008; Pederson 2011). More than 4500 proteins were identified by multiple mass spectrometry in highly purified preparations of human nucleoli (Ahmad et al. 2009). At the ultrastructural level, the functional nucleolus is composed of three subcompartments: fibrillar center, dense fibrillar component, and granular component. Each nucleolar domain contains a specific set of proteins that is associated with the processes that occur in the corresponding compartment.

To reveal the localization of a protein of interest, two major approaches are currently used: analysis of the distribution of chimeric proteins fused with different fluorescent proteins and immunocytochemistry. The former approach allows the study of the localization of a protein in vivo, thereby allowing for the wide application of this method (Chudakov et al. 2010). However, this approach has several restrictions. Even if the fluorescent protein that is fused does not influence the functional characteristics of the protein of interest, the expression of an exogenous protein usually increases the concentration of the protein investigated, which can lead to artifacts. For example, it was shown that (1) exogenous proteins can be localized differently from the endogenous protein (Maeshima and Laemmli 2003; Musinova et al. 2011) and that (2) the protein overexpression can significantly influence the formation of the structures in which it is distributed and even lead to the formation of de novo structures (Volkova et al. 2011). Therefore, in many cases, it is preferable to detect the localization of proteins using immunocytochemistry.

However, the use of specific antibodies does not always allow the identification of the location of a protein, even if the antibody is correctly bound to the antigens in preparations. For example, we have previously demonstrated that a higher concentration of an antigen within the nucleolus may prevent its proper recognition by specific antibodies (Sheval et al. 2005). In particular, it was shown that antibodies to fibrillarin can properly detect the protein in non-transfected cells or cells with a low level of exogenous fibrillarin expression. However, in cells with a high level of expression of exogenous fibrillarin, the protein cannot be detected in the intranucleolar regions and the antibodies labeled antigens only in the periphery of the nucleoli. Importantly, such strange peripheral staining was observed after the overexpression of fibrillarin (Sheval et al. 2005) and also in normal, non-transfected cells after the immunocytochemical detection of nucleophosmin/B23 (Zatsepina et al. 1997; Misteli 2008; Musinova et al. 2011). Furthermore, using postembedding immunoelectron microscopy in HeLa cells with specific antibodies, it was demonstrated that B23 was not localized to the nucleolar periphery but to the dense fibrillar component and the granular component (Biggiogera et al. 1989). Hence, this staining pattern is an artifact, and it is, therefore, important to find an approach for the proper detection of such proteins as B23. The process of immunogolding is a laborious method that cannot be widely used. Thus, the search for a method for the correct detection of nucleolar proteins using light microscopy is necessary. Here, we present the development of a simple and rapid method to detect nucleolar proteins in the interior of the nucleolus using specific antibodies.

Material and Methods

Plasmids

The EGFP-FLAG-B23/nucleophosmin plasmid (Wang et al. 2005) (Addgene plasmid 17578) was used for transfection. For the pTagRFP-fibrillarin plasmid construction, the region encoding human fibrillarin was amplified from cDNA (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the fibrillarin upstream primer (5′-ATATG- GATCCAAGTTCTTCACCTTGGGGGGTG-3′) and the fibrillarin downstream primer (5′-TATATAAGCTTGACCAT- GAAGCCAGGATTCAGTC-3′). The resulting PCR product was digested by BamHI and HindIII, gel purified, and cloned into the pTagRFP-N1 vector (Evrogen; Moscow, Russia).

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, and an antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). The cells were grown as monolayers on coverslips and used during the exponential growth phase. The cell transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunocytochemistry

For the immunofluorescent labeling, the cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, and 4.29 mM Na2HPO4; pH 7.3) or in cold (–20C) methanol. After permeabilization in 0.5% Triton X-100 solution and washing in PBS, the cells were incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min and, subsequently, with primary anti-B23 antibodies (#B0556; Sigma-Aldrich), anti–green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibodies (#ab1218; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), or anti-FLAG antibodies (#F1804; Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min at 25C. After several washes in PBS with 0.1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20, the cells were incubated with Alexa 488–conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (Invitrogen) for 45 min at 25C. After washing in PBS, the cells were mounted onto slides with Mowiol (Calbiochem; Darmstadt, Germany) containing the anti-bleaching agent DABCO (Sigma-Aldrich). The preparations obtained were observed microscopically with an Axiovert 200M (Carl Zeiss; Göttingen, Germany) equipped with a Neofluar 100×/1.3 oil immersion objective. The images were recorded with an ORCAII-ERG2 CCD-camera (Hamamatsu Photonics; Tokyo, Japan), and the image deconvolution was processed with the DeconvolutionLab plugin (Biomedical Imaging Group, EPFL; Lausanne, Switzerland) for ImageJ (National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD). In some cases, the specimens were analyzed using an LSM510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). For the final presentation, all of the images were saved as files in Adobe Photoshop CS2 (Adobe Systems; San Jose, CA) format.

To measure the total cell fluorescence, the images were recorded using a Neofluar 20×/0.5 objective. The intensity of the cell fluorescence was measured using the ImageJ software (available for free at http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The total cell fluorescence was estimated as the difference between the measured fluorescence of the cell and the background. The diagrams were plotted using the Statistica 6.0 software (StatSoft; Tulsa, OK).

Proteinase Treatment

After the permeabilization, the cells were incubated in a proteinase-containing solution at 37C. We used the following three different proteinases: (1) 2.5 µg/ml trypsin (Spofa; Prague, Czech Republic), (2) 50 µg/ml proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich), or (3) 10 µg/ml pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich). The trypsin and proteinase K were diluted in PBS and the pepsin in 0.01 N HCl. The reaction was terminated by transferring the slices to cold PBS (with the addition of 1 mM PMSF in the case of the trypsin treatment). For the determination of the optimal time of proteinase treatment, we carried out two preliminary experiments. In the first, we treated the cells with different concentrations of the proteinase for 5 min and chose the lowest concentration at which B23 was detected in the entire volume of the nucleolus. In the second experiment, we treated the cells with proteinase at selected concentrations for different times, which led to a more accurate determination of the optimal conditions. By using frozen aliquots of the proteinase tested, we could reproducibly obtain the proper staining pattern.

Immunogold Labeling

For the immunogolding, the primary and secondary antibody staining was carried out as described for the immunofluorescence using nanogold anti-mouse Fab-fragments (NanoProbe; Yaphank, NY) at a 1:250 dilution for 16 hr at 4C. The coverslips were washed in PBS and fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for 1 hr. Silver enhancement was performed as previously described (Gilerovitch al. 1995), followed by embedding in Epon 812.

Results

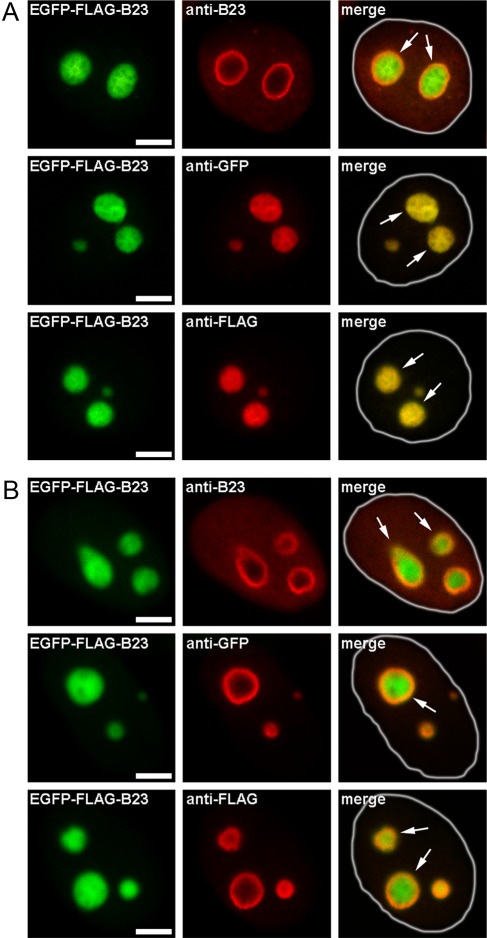

After the staining with the anti-B23 antibodies, B23 was detected only in the peripheral region of the nucleoli and nucleoplasm (data not shown). To ascertain whether the peripheral staining with the anti-B23 antibodies was due to the unavailability of the inner nucleolar region with a high antigen concentration, a previously developed approach (Sheval et al. 2005) was used. We expressed a chimeric B23 that contains two tags, EGFP and FLAG. The EGFP tag has its own fluorescence, whereas the FLAG tag can be detected by anti-FLAG antibodies. We initially analyzed the cells with a low expression of exogenous protein, and EGFP fluorescence was detected throughout the volume of the nucleolus—that is, the exogenous protein was distributed almost homogeneously throughout the nucleolus. However, the anti-B23 antibodies detected the protein only in the peripheral region of the nucleolus (Fig. 1A and Suppl. Fig. S1). Interestingly, both the anti-GFP and anti-FLAG antibodies detected the presence of the exogenous protein in the entire volume of the nucleolus, indicating that the inner regions were accessible to the antibodies (Fig. 1A). All of the antibodies used were mouse IgG immunoglobulins, and, therefore, the incorrect labeling in the case of the anti-B23 antibodies was not a consequence of the larger size of the molecules. Thus, the explanation for this observation may be the fact that the antibodies against B23 bound to both the exogenous and endogenous protein; that is, the concentration of this antigen in the nucleolus was high. The concentrations of the exogenous proteins detected by the anti-GFP and anti-FLAG antibodies were low; therefore, these antibodies easily detected the antigens in the inner region of the nucleolus.

Figure 1.

Immunocytochemical determination of antigen localization in cells expressing EGFP-FLAG-B23 at low (A) and high (B) levels. The conditions of the image recording were selected in such a way that the brightness of the final images was approximately the same, independently of the level of exogenous protein expression. Thus, the cells with low expression are the cells that were recorded with a higher value of gain of photomultiplier tube and vice versa. (A) Cells expressing low levels of exogenous protein stained with anti-B23, anti-GFP, and anti-FLAG antibodies. The localization of exogenous protein may be determined by EGFP fluorescence. (B) Staining of cells expressing high levels of exogenous protein. The nuclei are surrounded with white lines in merge images. The nucleoli are indicated with arrows. GFP, green fluorescent protein; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein. Bar = 5 µm.

Importantly, when we analyzed the cells overexpressing this fusion protein, all three of the antibodies (anti-B23, anti-GFP, and anti-FLAG) preferentially detected the protein on the nucleolar periphery (Fig. 1B). Thus, it appears that a high concentration of the antigen within the nucleolus prevented the proper recognition by the antibodies.

In all of the subsequent experiments, we analyzed (1) the staining pattern (peripheral of homogeneous) and (2) the total fluorescence intensity of the nucleus. The second indicator was chosen considering that when the antibody penetrates into the interior of the nucleolus and binds with the antigens, the overall intensity of the nuclear staining must be increased.

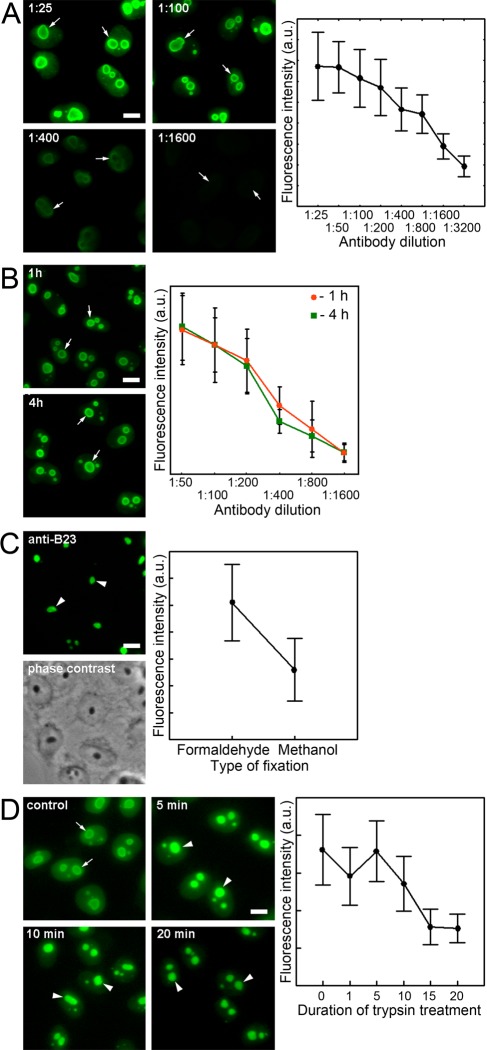

One can assume that the incorrect staining was due to a high concentration of antigen and also to an incorrectly matched antibody concentration or incubation time. Reducing the concentration of the antibodies led to a decrease in the overall intensity of staining of the nuclei; however, the peripheral staining of the nucleoli was detected in all cases (Fig. 2A). Moreover, increasing the staining time (up to 4 hr) did not improve the detection of B23 in the interior of the nucleoli (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical localization of B23 in HeLa cells (morphology pattern and overall intensity of cell fluorescence [mean ± SD]). (A) Different dilutions of primary antibodies. (B) Different times of staining with primary antibodies (1 hr and 4 hr). (C) Fixation with methanol. (D) Treatment of formaldehyde-fixed cells with trypsin. Nucleoli are indicated either by arrows (if the anti-B23 antibodies detected the protein only in the peripheral region of the nucleoli) or by arrowheads (if the anti-B23 antibodies detected the protein in the entire volume of the nucleoli). It should be noted that the fixation with methanol led to nucleolus shrinkage. Bars = 10 µm.

In addition, the peculiarities of the formaldehyde fixation protocol (formaldehyde concentration, time of fixation, and treatment with Triton X-100 before or during fixation) did not influence the staining pattern (data not shown). However, B23 was detected in the entire volume of the nucleolus after the fixation with cold methanol (Fig. 2C). There was a complete extraction of the protein from the nucleoplasm and a 2-fold decrease of the total fluorescence intensity of the nuclei after the methanol fixation, indicating that B23 was significantly extracted during the fixation with methanol.

Thus, using methanol fixation, it was possible to identify B23 in the nucleolar interior, but this fixation protocol significantly changed the cellular morphology and should be used with restrictions. One can assume that a decrease of the nucleolar density may increase the accessibility of the interior regions for antibodies. After a short hypotonic treatment, which leads to a partial disassembly of the nucleolus, it was not possible to detect B23 in the interior of the nucleolus (data not shown). Subsequently, we used enzymatic treatments (with DNase I, RNase A, and trypsin) on fixed cells to reduce the density of the cellular contents; B23 was detected in the inner regions of the nucleolus only after the trypsin treatment (Fig. 2D). On the basis of the decrease of the total fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2D), we conclude that B23 was gradually digested during the trypsin treatment. Similar results were obtained after the use of proteinase K and pepsin (data not shown). In the subsequent experiments, we used trypsin because this enzyme works at a physiological pH and can be irreversibly inhibited by PMSF.

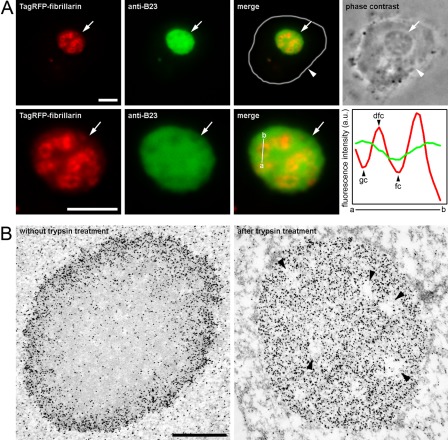

It was principally important to determine whether this approach was compatible with the other methods of cell morphological studies (primarily, the simultaneous detection of other proteins and electron microscopy). We expressed TagRFP-fibrillarin, which is localized mainly in the dense fibrillar component, and we then investigated the morphology of the cells digested with trypsin. The treatment with trypsin led to a gradual decrease in the fluorescence intensity of TagRFP-fibrillarin; however, after a short trypsin treatment, it was possible to detect both TagRFP-fibrillarin and B23 in the nucleolar interior (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

The compatibility of proteinase treatment with different methods of morphological investigation. (A) The localization of TagRFP-fibrillarin in cells digested with trypsin (top panels—overall view; bottom view—enlarged nucleolus). The nucleus is surrounded by a white line in the merge image and indicated by arrowheads. The nucleolus is indicated by arrows. The fibrillar centers are surrounded by the fibrillarin-containing dense fibrillar component. The right panel in the bottom row demonstrates a plot of intensity values along the selected line (a–b) in the merge panel (green line, B23; red line, TagRFP-fibrillarin). Fc, fibrillar center; dfc, dense fibrillar component; gc, granular component. (B) Ultrastructural visualization of B23 localization using the preembedding technique. Left panel—control; right panel—cells treated with trypsin after formaldehyde fixation. The putative fibrillar centers are indicated by black arrowheads. Bars = 5 µm (A) and 1 µm (B).

In addition, we investigated the localization of B23 using immunogold at the ultrastructural level. We used nanogold labeling with a subsequent silver enhancement. This approach is not ideal in terms of cellular morphology preservation, but it allows for the ultrastructural analysis of a large number of objects selected using a light microscope, which is necessary for some studies (Maeshima et al. 2005; Sheval and Polyakov 2006, 2008). In control cells, B23 was detected in the nucleoplasm and in the peripheral layer of the nucleolus (Fig. 3B). After treatment with trypsin, the entire nucleolus was intensely labeled, except for small rounded areas (possibly the fibrillar centers).

Discussion

The developed approach can successfully remove one of the limitations of immunocytochemistry, the incorrect identification of some nucleolar protein localization using specific antibodies. However, the mechanism of such inaccessibility of the intranucleolar region for antibodies is not clear. The antibodies to several proteins (including anti-GFP and anti-FLAG antibodies) properly label their antigens inside the nucleoli, but when the antigen is overexpressed (such as EGFP-FLAG-B23 in the present work), the same antigens cannot be labeled by the same antibodies inside the nucleoli. Similar difficulties have been found with such abundant proteins as B23 (Zatsepina et al. 1997; Misteli 2008; Musinova et al. 2011; this study). One can speculate that the antibodies that were bound to abundant antigens at the nucleolar periphery created a mechanical barrier against the further penetration into the inner region of the nucleoli.

After analyzing a large number of the different variables of fixation, staining, and the processing of cells (only a small portion of our experiments is described herein), we found two ways to detect B23 in the interior of the nucleolus using specific antibodies: the fixation with methanol and the treatment of the fixed cells with proteases (trypsin, proteinase K, and pepsin). The former method significantly changed the cellular morphology and led to strong protein extraction, whereas the latter method required a diligent selection of proteinase treatment conditions. Furthermore, the proteinase treatment partially destroyed the proteins, and, therefore, this method cannot be recommended for the quantitative estimation of proteins.

According to published data, proteinase treatments were used for antigen unmasking in histological sections (Islam et al. 1988; Niehans et al. 1988). Here, we used a similar methodological approach to resolve a different problem: the detection by specific antibodies of proteins in nucleolar regions with a high antigen concentration. It should be noted that the approach developed is necessary only for the visualization of the antigen inside regions with a high concentration of antigen. In cases in which the protein localizes to a small intranucleolar region or its concentration is not high, the antigens may be detected without the proteinase treatment. For example, the localization of 21 intranucleolar proteins was recently described by standard immunocytochemistry (Hutten et al. 2011).

Thus, the method described here with proteinase treatment is useful only in specific situations when standard immunocytochemistry does not allow the proper detection of the protein localization.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. X.W. Wang for providing EGFP-FLAG-B23 construct. We thank E.P. Senchenkov, A.V. Lazarev, and M.Y. Mogilnikov for technical support.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article is available on the Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry Web site at http://jhc.sagepub.com/supplemental.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This work was supported by grant from Russian Foundation for Basic Research (09-04-01430 and 12-04-01237), and President’s Grant for Young Scientists (MK-1332.2010.4).

References

- Ahmad Y, Boisvert FM, Gregor P, Cobley A, Lamond AI. 2009. NOPdb: Nucleolar Proteome Database—2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D181–D184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggiogera M, Fakan S, Kaufmann SH, Black A, Shaper JH, Busch H. 1989. Simultaneous immunoelectron microscopic visualization of protein B23 and C23 distribution in the HeLa cell nucleolus. J Histochem Cytochem. 37:1371–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudakov DM, Matz MV, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA. 2010. Fluorescent proteins and their applications in imaging living cells and tissues. Physiol Rev. 90(3):1103–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cmarko D, Smigova J, Minichova L, Popov A. 2008. Nucleolus: the ribosome factory. Histol Histopathol. 23(10):1291–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilerovitch HG, Bishop GA, King JS, Burry RW. 1995. The use of electron microscopic immunocytochemistry with silver-enhanced 1.4-nm gold particles to localize GAD in the cerebellar nuclei. J Histochem Cytochem. 43:337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutten S, Prescott A, James J, Riesenberg S, Boulon S, Lam YW, Lamond AI. 2011. An intranucleolar body associated with rDNA. Chromosoma. 120:481–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam A, Archimbaud E, Henderson ES, Han T. 1988. Glycol methacrylate (GMA) embedding for light microscopy: II. Immunohistochemical analysis of semithin sections of undecalcified marrow cores. J Clin Pathol. 41:892–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima K, Eltsov M, Laemmli UK. 2005. Chromosome structure: improved immunolabeling for electron microscopy. Chromosoma. 114(5):365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima K, Laemmli UK. 2003. A two-step scaffolding model for mitotic chromosome assembly. Dev Cell. 4(4):467–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T. 2008. Physiological importance of RNA and protein mobility in the cell nucleus. Histochem Cell Biol. 129(1):5–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musinova YR, Lisitsyna OM, Golyshev SA, Tuzhikov AI, Polyakov VY, Sheval EV. 2011. Nucleolar localization/retention signal is responsible for transient accumulation of histone H2B in the nucleolus through electrostatic interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813:27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehans GA, Manivel JC, Copland GT, Scheithauer BW, Wick MR. 1988. Immunohistochemistry of germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms. Cancer. 62:1113–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson T. 2011. The nucleolus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3:a000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheval EV, Polyakov VY. 2006. Visualization of the chromosome scaffold and intermediates of loop domain compaction in extracted mitotic cells. Cell Biol Int. 30:1028–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheval EV, Polyakov VY. 2008. The peripheral chromosome scaffold, a novel structural component of mitotic chromosomes. Cell Biol Int. 32:708–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheval EV, Polzikov MA, Olson MOJ, Zatsepina OV. 2005. A higher concentration of an antigen within the nucleolus may prevent its proper recognition by specific antibodies. Eur J Histochem. 49:117–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkova EG, Kurchashova SY, Polyakov VY, Sheval EV. 2011. Self-organization of cellular structures induced by the overexpression of nuclear envelope proteins: a correlative light and electron microscopy study. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 60:57–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Budhu A, Forgues M, Wang XW. 2005. Temporal and spatial control of nucleophosmin by the Ran-Crm1 complex in centrosome duplication. Nat Cell Biol. 7:823–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatsepina OV, Todorov IT, Philipova RN, Krachmarov CP, Trendelenburg MF, Jordan EG. 1997. Cell cycle–dependent translocations of a major nucleolar phosphoprotein, B23, and some characteristics of its variants. Eur J Cell Biol. 73:58–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]