Background: Cdk5 participates in the regulation of nociceptive signaling and peripheral inflammation increase its activity.

Results: TGF-β1, an immunoregulatory cytokine that plays a key role during inflammation, can increase Cdk5 activity.

Conclusion: There is active cross-talk between TGF-β and Cdk5 signaling pathways that affects pain.

Significance: Understanding the cross-talk between inflammation and pain signaling is important for developing novel therapies to treat pain associated with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Inflammation, Pain, Transforming Growth Factor β (TGFβ), TRP Channels, Sensory Neurons

Abstract

In addition to many important roles for Cdk5 in brain development and synaptic function, we reported previously that Cdk5 regulates inflammatory pain signaling, partly through phosphorylation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), an important Na+/Ca2+ channel expressed in primary nociceptive afferent nerves. Because TGF-β regulates inflammatory processes and its receptor is expressed in TRPV1-positive afferents, we studied the cross-talk between these two pathways in sensory neurons during experimental peripheral inflammation. We demonstrate that TGF-β1 increases transcription and protein levels of the Cdk5 co-activator p35 through ERK1/2, resulting in an increase in Cdk5 activity in rat B104 neuroblastoma cells. Additionally, TGF-β1 enhances the capsaicin-induced Ca2+ influx in cultured primary neurons from dorsal root ganglia (DRG). Importantly, Cdk5 activity was reduced in the trigeminal ganglia and DRG of 14-day-old TGF-β1 knock-out mice, resulting in reduced Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of TRPV1. The decreased Cdk5 activity is associated with attenuated thermal hyperalgesia in TGF-β1 receptor conditional knock-out mice, where TGF-β signaling is significantly reduced in trigeminal ganglia and DRG. Collectively, our results indicate that active cross-talk between the TGF-β and Cdk5 pathways contributes to inflammatory pain signaling.

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5)2 is a proline-directed serine/threonine kinase that belongs to the family of cyclin-dependent protein kinases. Cdk5 kinase activity is mainly present in postmitotic neurons where its activators, p35 and p39, are predominantly expressed (for review see Refs. 1 and 2). Mice lacking either Cdk5 (3) or both p35 and p39 (4) exhibit abnormal corticogenesis and perinatal lethality, underlining a crucial role of Cdk5 activity in the developing brain. Moreover, Cdk5 is critical for neuronal survival (5) and prevents neuronal apoptosis by negative regulation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 (6). Although earlier studies focused on delineating the molecular roles of Cdk5 in brain development, more recent work has implicated Cdk5 in many other functions in the mature brain such as memory, learning, and cellular processes leading to neurodegeneration (1). We, and others, have reported that Cdk5 activity participates in the regulation of nociceptive signaling (7–9). An elevated Cdk5 activity associated with the increased expression of Cdk5 and p35 occurs in nociceptive primary afferent neurons during peripheral inflammation (7). Furthermore, we observed that peripheral inflammation increased Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a ligand-gated ion channel critically involved in thermal and inflammatory pain (10). We subsequently demonstrated that tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) regulates Cdk5 activity during pain signaling through transcriptional activation of p35 (11, 12). Pharmacological modulation of Cdk5 can produce analgesia or anti-hyperalgesia. We observed that resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound with known analgesic activity, can inhibit Cdk5 activity through decreased expression of p35 (13). Intraplantar injection of roscovitine, a Cdk5 inhibitor, or intrathecal administration of Cdk5 siRNA blocked the development of hyperalgesia in a complete Freund's adjuvant model of inflammation (8). Additionally, Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of the δ-opioid receptor impaired receptor function and attenuated anti-nociceptive tolerance for morphine (14). These findings suggest that Cdk5 plays an important role in multiple molecular mechanisms involved in pain signaling and modulation.

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is an important member of a superfamily of multifunctional growth factors involved in many cellular processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis (15). Our earlier studies and those of others on the characterization of the Tgf-β1−/− mouse phenotype confirmed TGF-β1 as a key regulator of inflammation (16, 17). TGF-β1−/− mice developed a rapid wasting syndrome and died by 3–4 weeks of age. As early as 2 weeks, these mice displayed multifocal inflammation with massive infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages into several organs, but principally into the heart, lungs, and salivary glands (17, 18). Multiple actions of TGF-β1 have been reported in the CNS. TGF-β1 is normally present at low levels in healthy adult CNS cells, but it is rapidly up-regulated following injury and directly induces expression of several injury-related genes (19). Although TGF-β1 is known to promote survival of neurons, its precise mechanism is still not clear (20, 21). TGF-β1 has also been implicated in the pathology of Alzheimer disease (22, 23) and its overexpression in astrocytes can lead to excessive deposition of extracellular matrix components in the brain resulting in neurological disease (24). Recent reports indicate that TGF-β1 may play a role in migraine and neuropathic pain (25–27). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying its involvement in nociceptive signaling are still far from clear. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to explore a possible cross-talk between Cdk5 and TGF-β signaling pathways, and the influence of the cross-talk on inflammation-induced nociceptive responses.

Here we used in vitro and in vivo approaches to study the role of TGF-β1 in the regulation of Cdk5 activity and its involvement in inflammatory pain signaling. We found that TGF-β1 increases Cdk5 activity in B104 neuroblastoma cells and causes increased Cdk5-dependent TRPV1 phosphorylation and capsaicin-induced Ca2+ influx in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) primary cultures. Likewise, a deficiency of TGF-β signaling in TGF-β1−/− mice, or where transforming growth factor-β receptor 1 (Tgfbr1) is conditionally knocked out in TG and DRG, resulted in reduced Cdk5 activity and attenuated thermal hyperalgesia, suggesting an active cross-talk between TGF-β and Cdk5 pathways in sensory afferents during peripheral inflammatory states.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and TGF-β1 Treatment

The rat neuroblastoma B104 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT). After deprivation of serum, B104 cells were treated with TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or SB431542 (Sigma) for the indicated times, and then proteins or total RNA were extracted.

Transient Transfection and Reporter Activity Assays

One hour before transfection, medium with serum was replaced by Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Transfection of the p35 promoter-luciferase vector (11) into B104 cells was performed using LipofectamineTM LTX and PlusTM Reagent (Invitrogen). Six hundred nanograms (ng) of p35 promoter-LUC and 200 ng of control vector Renilla luciferase expressed under the constitutive promoter of thymidine kinase (Promega, Madison, WI) were co-transfected into 4 × 104 cells. After the transfection, the cells were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Total proteins were extracted from the treated cells, and the luciferase activity was measured with a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), and the results were presented as the relative p35 promoter activity, which was calculated by dividing the mean value of p35 promoter luciferase activity by the mean value of Renilla luciferase activity.

DRG Primary Culture

Individual DRGs were dissected from postnatal 21-day-old mice and then dissociated in Ca2+/Mg2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution containing Liberase Blendzyme 3 (0.5 units/ml, Roche Applied Science) for 1 h. DRGs were then triturated using a fire-polished glass pipette and enriched for neurons by spinning on a two-layer Percoll gradient (30 and 50%). After removing the Percoll, cells were re-suspended in minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated horse serum and plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated 25-mm diameter coverslips, then cultured for 4 to 6 days before measurement. Primary DRG cultures at this stage were treated with either TGF-β1 or SB431542, or both, for 24 h. Proteins were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting. Mouse DRG cultures were also used for intracellular Ca2+ measurements.

Measurement of Intracellular Ca2+

Mouse DRG cells were loaded with 2.5 μm of the high Kd calcium indicator fura-4F AM (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) in the presence of 0.025% Pluronic® F-127 (Invitrogen) in normal perfusion medium (in mm: 2.5 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 Hepes, 3 KCl, 0.6 MgCl2, 130 NaCl, pH adjusted with 1 m Tris base to 7.4, and osmolarity adjusted with 50 mm sucrose to 325 mosmol/liter) for 45 min at room temperature. This was followed by a wash and further incubation in perfusion medium for an additional 15 min. The coverslip was inverted and mounted onto a closed flow-through perfusion chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) with a nominal bath volume of 358 μl, then perfused continuously at a rate of 0.5 ml/min using a Minipuls 3 peristaltic pump (Gilson, Middleton, WI). All experiments were performed at room temperature. Fluorescence data were acquired on a PC running MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices, Silicon Valley, CA) via a CCD camera (ORCA-ER, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) connected to an upright microscope (BX60, Olympus, Japan) using a ×20 water-immersion objective. The ratio of fluorescence emission (510 nm) in response to 340/380 nm excitation, controlled by a filter changer (Lambda 10-2, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA), was acquired continuously at 0.5 Hz. Capsaicin (1 mm ethanol stock) was diluted to 400 nm and administered via an in-line manual sample injector (number 7010, Rheodyne, United Kingdom) equipped with a 500-μl sample loop. We determined 400 nm capsaicin to be an EC100 dose for activating TRPV1+ DRG neurons but did not saturate the response. The perfusion medium was supplemented with 1 mm ascorbate during experiments to prevent oxidation of capsaicin. Cells were recorded for 12 min total: baseline for 2 min, followed by a 1-min capsaicin pulse and 9-min recovery. Activated cells were individually identified and their corresponding 340/380 ratios were measured using the MetaFluor analysis software. Based on the calibration method of Grynkiewicz et al. (28), ratios were converted to calcium concentration where [Ca2+]i (intracellular) = Kd × Q × (R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R). For our DRG cultures, Kd = 770 nm, Q = 2.53, Rmin = 0.33, and Rmax = 3.7. Experiments were performed in triplicate, using fresh DRG cultures for each repeat. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (San Diego, CA).

RNA Isolation and Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from B104 cells or from nociceptive tissues, DRG, and TG from Tgfbr1 cKO mice using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following TURBO DNA-freeTM (Ambion, Austin, TX) digestion of the total RNA sample, to remove contaminated genomic DNA, oligo(dT)-primed synthesis of cDNA from 3 μg of total RNA was made using Super-ScriptTM III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). We used real-time RT-PCR with the following reaction mixture: 1 × IQTM SYBR® Green Super Mix (Bio-Rad), 400 nm of each primer, and 10 μl of cDNA to determine mRNA levels of Cdk5, p35, Egr-1, and S29. cDNA was amplified and analyzed in triplicate using Opticon Monitor Chomo 4 (Bio-Rad). The following primers used for real time RT-PCR were: p35 (F), 5′-GCC CTT CCT GGT AGA GAG CTG-3′, p35 (R), 5′-GTG TGA AAT AGT GTG GGT CGG C-3′; Egr-1 (F), 5′-CCC TTC CAG GGT CTG GAG AAC CGT-3′, Egr-1 (R), 5′-GGG GTA CTT GCG CAT GCG GCT GGG-3′; S29 (F), 5′-GGA GTC ACC CAC GGA AGT TCG G-3′; S29 (R), 5′-GGA AGC ACT GGC GGC ACA TG-3′; Tgfbr1 (F), 5′-TGC ATT GCA CTT ATG CTG ATG GT-3′, Tgfbr1 (R), 5′-ACC TGA TCC AGA CCC TGA TGT T-3′; and NeuN (F), 5′-GGC AAT GGT GGG ACT CAA AA-3′, NeuN (R), 5′-GGG ACC CGC TCC TTC AAC-3′.

Animals

Wild type 21-day-old mice were used to obtain DRG for neuronal cultures. Tgf-β1−/− knock-out mice were previously generated in our laboratory and maintained on a mixed C57BL/6J background and genotyping was performed as previously described (29). Protein from TG and DRG were obtained from 2-week-old TGF-β1−/− mice. The Tgfbr1 cKO mice (SNS-Cre; Tgfbr1f/f) were generated from crosses between Tgfr1f/f mice (30) and SNS-Cre mice (31). The Tgfbr1 cKO mice and their controls were from the same litter had exactly the same C57BL/6J genetic background. Behavioral studies were conducted and histological and molecular end point was taken when mice were 5–6 weeks old. Studies were performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health's Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory and Experimental Animals. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Antibodies

Antibodies to Cdk5, p35, TRPV1, and secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibodies) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-phospho-T407-TRPV1 antibody was generated previously (10). Phospho-Smad2 antibody was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA), total Smad2 antibody was obtained from Invitrogen, α-tubulin antibody was obtained from Sigma.

Western Blot Analysis

Homogenates of nociceptive tissues or B104 cells were lysed in T-PER buffer from Thermo Scientific with a tablet of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Complete Mini and PhosSTOP, from Roche Applied Science). Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) and similar quantities were separated on 4–12 or 3–8% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). The membranes were soaked in a blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk powder in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween® 20, PBST) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the appropriate primary antibody diluted in the blocking buffer. The membranes were washed in PBST and incubated for 1 h at room temperature, with the secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Immunoreactivity was detected using SuperSignal West Pico or West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific). The membranes were stripped for 15 min at room temperature with Re-blot Plus Strong Solution (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and retested with α-tubulin antibodies to normalize for protein loading. The optical densities of the bands were quantified using an image analysis system with Scion Image Alpha 4.0.3.2 software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD).

Cdk5 Kinase Activity

Cdk5 kinase activities were measured as described (11). In brief, 250–500 μg of protein from B104 cells, TGs, or DRGs were dissolved in T-PER buffer and immunoprecipitated overnight with 2.5 μg of Cdk5 antibody (C8). After washing, immunoprecipitates were mixed with kinase assay buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EDTA, and 5 mm dithiothreitol, pH 7.4) and histone H1 (1 μg/μl) was used as a substrate. The kinase activity was quantified as described (11).

Thermal Stimulus and Behavioral Testing Paradigm

One- to 2-month-old Tgfbr1 cKO and littermate mice were used for behavioral assessment of thermal nociception. An infrared diode laser (LASS-10M; Lasmed, LLC, Mountain View, CA) with an output wavelength of 980 nm and maximum power of 20 watts was used to generate thermal stimuli. For calibration, laser power/energy was measured using a meter with a thermal sensor (Nova II, L30A-10 MM, Ophir Optronics). Beam diameter was changed by adjusting the distance from the beam collimator to the skin. Cutaneous afferents were activated either by low-rate (≤1.5 °C) heating using long pulses, low energy, and a large diameter beam (5 mm Ø, nominal) or by a high rate (≥150 °C) of heating, using a high-energy, short pulse (100 ms), and a small beam diameter (1.6 mm Ø, nominal). Under these parameters, long pulses preferentially activate C-fibers, and short pulses preferentially activate Aδ fibers (32, 33). Long-pulse responses were evaluated at three laser current settings, 650, 750, and 850 mA, and short-pulse responses were evaluated at 2500, 3000, 3500, and 4000 mA. These settings were determined in pilot studies to elicit consistent nociceptive responses from normal adult mice. The testing paradigm is similar to what we established earlier using a radiant heat stimulus from a focused incandescent light source (34). Briefly, the mice were placed unrestrained under plastic enclosures on an elevated glass platform. The enclosures were large enough for the animals to move freely, and mice were habituated for 15–30 min before testing. The laser collimator was attached to a support and positioned below the glass, with the beam perpendicular to the surface. The end point for the long-pulse (C-fiber) response is paw withdrawal latency. In this case, the beam was aimed at the mid-plantar foot pad and the paw continuously stimulated until withdrawal, which manifested as either an abrupt movement of the foot away from the stimulus or rapid, repeated flinching. Latency was measured by the experimenter using a digital stopwatch. Short-pulse (Aδ fiber) evaluation involved stimulation of the mid-plantar footpad or heel, one stimulation (1 trial) per paw per mouse at each energy setting. The response to the short-pulse stimulus in normal mice is brisk, behaviorally productive, and dependent on laser intensity (32, 35). The stimulus is so short and the withdrawal so fast that latency is not an informative end point; additionally, the range of motion is limited in young mice. We instead use a binary measure (no withdrawal = 0, withdrawal = 1) and calculate the probability of withdrawal to each stimulus intensity (total withdrawals/total number of trials). Withdrawal was defined as an immediate (≤1 s), abrupt movement or flinching of the foot after stimulation. The inter-stimulus interval, per trial, was typically ≥1 min. Stimulus intensity was progressively increased during the session. If performed on the same day, responses to long-pulse stimuli were determined after evaluation of short-pulse responses. Because the beam diameter is small, the mouse paw can easily accommodate the three Aδ stimuli without repeated application on the same spot. In all cases the experimenter was blinded to the genotype of the mice being analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed a minimum of three times. Statistical evaluation was performed with GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Significant differences between experiments were assessed by an unpaired t test where α was set to 0.05.

RESULTS

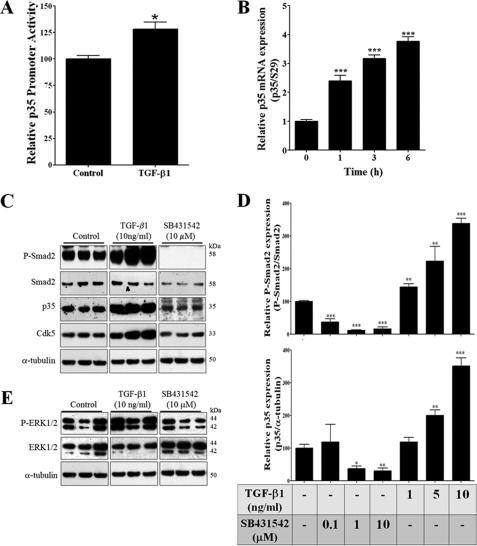

TGF-β1 Increased p35 Promoter Activity and p35 mRNA Levels in Rat B104 Neuroblastoma Cells

Previously, we discovered that the expression level of p35 is the limiting factor for Cdk5 activity (36). Furthermore, we found that the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α increases p35 promoter activity with a subsequent increase in Cdk5 activity in PC12 cells (11). Because TGF-β signaling is not activated by TGF-β1 treatment in PC12 cells due to low expression of Tgfbr2 (37), we used rat B104 neuroblastoma cells that are responsive to TGF-β1 treatment (38, 39) and are also similar to neuronal progenitors (40). B104 cells were transiently co-transfected with p35 promoter-LUC vector (11) and Renilla luciferase-thymidine kinase vector (control for transfection efficiency) and treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h, and then luciferase activity was measured. We found that TGF-β1 treatment significantly increased p35 promoter activity as compared with control cells (Fig. 1A). To further confirm that TGF-β1 activates p35 promoter activity, we examined endogenous p35 mRNA levels in B104 cells following the treatment with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) at different time points (0, 1, 3, and 6 h). p35 mRNA levels were significantly increased within 1 h after TGF-β1 treatment, and at 3 and 6 h this increase was more than 3-fold (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

TGF-β1 increased p35 and Cdk5 expression in rat B104 neuroblastoma cells. A, rat B104 cells transiently co-transfected with p35 promoter-LUC vector and Renilla luciferase-thymidine kinase vectors were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h and luciferase activity was measured. B, RNA was isolated from rat B104 cells treated with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) at 0, 1, 3, and 6 h and p35 mRNA levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR. C, representative Western blot of phospho-Smad-2, Smad-2, p35, and Cdk5 from B104 cells treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) or SB431542 (10 μm) for 24 h. D, quantification of the relative protein levels of P-Smad2 and p35 from B104 cells treated with TGF-β1 (1, 5, and 10 ng/ml) or SB431542 (0.1, 1, and 10 μm) during 24 h. E, a representative Western blot analysis of P-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 from B104 cells treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) or SB431542 (10 μm) during 24 h. The bars represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.005 as compared with control cells (Student's t test).

TGF-β1 Treatment Increased p35 Protein Levels in Rat B104 Neuroblastoma Cells

To confirm previous reports that B104 cells are responsive to TGF-β1 (38, 39), we treated B104 cells for 24 h with different concentrations of TGF-β1 (1, 5, and 10 ng/ml) or with increased concentrations of SB431542 (0.1, 1, and 10 μm), an inhibitor of Tgfbr1. We found that TGF-β1 treatment increased phosphorylation of Smad2, whereas SB431542 treatment decreased phosphorylation of Smad2 in a dose-dependent manner in B104 cells (Fig. 1, C and D). Likewise, the increase in p35 mRNA levels induced by TGF-β1 treatment correlated with increased p35 protein levels starting at 5 ng/ml of TGF-β1 and increasing to 4-fold higher at a TGF-β1 concentration of 10 ng/ml (Fig. 1, C and D). In addition, p35 protein levels were inhibited by SB431542 treatment starting at 1 μm and reaching more than 60% of inhibition at 10 μm (Fig. 1, C and D). TGF-β1 treatment at 10 ng/ml also resulted in an increased Cdk5 protein level (Fig. 1C). TGF-β1 treatment also increased phospho-ERK1/2 expression, whereas SB431542 treatment inhibited this phosphorylation (Fig. 1E).

TGF-β1 Treatment Increased Cdk5 Activity in Rat B104 Neuroblastoma Cells

We determined whether the TGF-β1-mediated increase in p35 expression results in increased Cdk5 activity. We immunoprecipitated Cdk5 protein from B104 cells treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of TGF-β1 (1, 5, and 10 ng/ml) and SB431542 (0.1, 1, and 10 μm) and assayed kinase activity using histone H1 as a substrate. Similar to the p35 protein levels (Fig. 1, C and D), Cdk5 kinase activity was significantly increased by TGF-β1 treatment, whereas it was decreased with SB431542 treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Cdk5 kinase activity did not increase with simultaneous treatment of TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) and SB431542 (10 μm) for 24 h suggesting that SB431542 blocks the TGF-β1-mediated increase in Cdk5 activity (Fig. 2B). To identify the molecular mechanism underlying TGF-β1-mediated regulation of Cdk5 activity, we determined the effects of TGF-β1 treatment on ERK1/2 activation. We made use of U0126, a specific MEK inhibitor, to inhibit ERK1/2 activation. U0126 treatment decreased Cdk5 activity and furthermore, also blocked the TGF-β1-mediated increase in Cdk5 activity (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

TGF-β1 increased Cdk5 activity in rat B104 neuroblastoma cells. A, upper panel shows a representative Cdk5 kinase activity of B104 cells treated with TGF-β1 (1, 5, and 10 ng/ml) and SB431542 (0.1, 1, and 10 μm) during 24 h. Lower panel shows that TGF-β1 increased, whereas SB431542 inhibited, Cdk5 kinase activity. B, upper panel shows a representative Cdk5 kinase activity of B104 cells pre-treatment with SB431542 (10 μm) for 1 h and then TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) during 24 h. Lower panel shows that TGF-β1-mediated Cdk5 kinase activity increased was blocked by SB431542. C, Cdk5 kinase activity of B104 cells were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml), U0126 (10 μm), or pre-treated with U0126 (10 μm) for 1 h and TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) during 24 h. D, RNA was isolated from rat B104 cells treated with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) at 0, 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h and Egr-1 mRNA levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR. The bars represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.005 as compared with control cells (Student's t test). #, p < 0.01 TGF-β1 versus TGF-β1 plus SB431542 treatment (Bonferroni's test after analysis of variance).

TGF-β1 Treatment Increased Egr-1 Expression in Rat B104 Neuroblastoma Cells

We have earlier reported that the TNF-α-mediated increase in p35 expression is dependent on ERK1/2 activation and an increase in expression of transcription factor Egr-1, a known regulator of the p35 promoter (11, 41). To evaluate if TGF-β1 treatment also regulates Egr-1 expression, we measured Egr-1 mRNA levels by real-time RT-PCR after TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) treatment at different time points (0, 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h) in B104 cells. We found that Egr-1 mRNA levels increased significantly within 30 min, reached a plateau at 1 h, and decreased to a basal level at 6 h following TGF-β1 treatment (Fig. 2D). Together these results suggest that TGF-β1 induces sustained and robust expression of Cdk5 and p35 in B104 cells, thereby increasing Cdk5 kinase activity. The activation of ERK1/2 by TGF-β1 leads to an increase in Egr-1 expression and subsequent elevation of p35 expression.

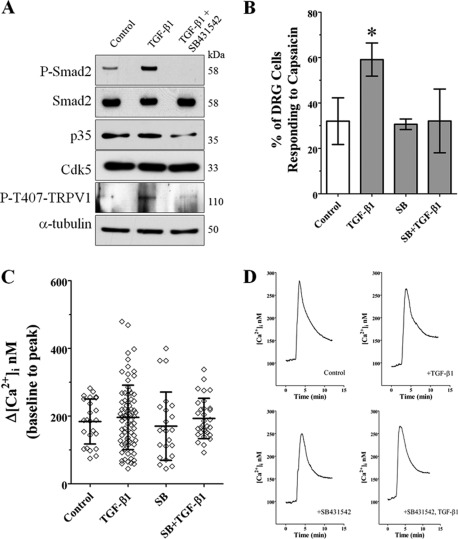

TGF-β1 Treatment Increases Cdk5-mediated Phosphorylation of TRPV1 Resulting in Increased Intracellular Ca2+ Influx in DRG Neurons in Primary Culture

Because TGF-β1 treatment increased Cdk5 activity in B104 cells, and Cdk5 has been shown to phosphorylate TRPV1 at Thr-407 in DRG (10), we evaluated whether TGF-β1 treatment can also increase the Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1, and whether this phosphorylation has any consequences on TRPV1 function in the DRG primary culture. TRPV1 is a sodium/calcium ion channel expressed in primary nociceptive afferent nerves and is important for depolarization of the nerve endings. DRG neurons obtained from postnatal 21-day-old wild type mice were cultured for 4 days, treated with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), or pre-treated with SB431542 (10 μm) for 1 h followed by TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), and then analyzed by Western blotting. In untreated DRG cells, we detected the basal level of phospho-Smad2, and TGF-β1 treatment significantly increased these levels; however, pre-treatment with SB431542 completely inhibited this increase in phospho-Smad2 (Fig. 3A). TGF-β1 treatment also increased phospho-T407-TRPV1 in DRG cultures, whereas pre-treatment with SB431542 abolished this effect (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, we found that the p35 protein levels were decreased by treatment with both SB431542 (10 μm) and TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) suggesting a parallel decrease in Cdk5 kinase activity that could result in attenuated TRPV1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A). To evaluate whether increased TRPV1 phosphorylation in DRG cells treated with TGF-β1 has a physiological effect, we examined capsaicin-induced calcium influx in cultured postnatal DRG neurons (28). Ca2+ influx was measured in DRG cultures treated with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), SB431542 (10 μm), or pre-treated with SB431542 (10 μm) for 10 min and followed by the addition of TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), all for 24 h. Across all the cultures analyzed, we found that the fraction of DRG cells responding to capsaicin (400 nm) was significantly increased following the TGF-β1 treatment (79/136 neurons; Fig. 3B). The percentage of capsaicin-responsive DRG cells treated with SB431542 (23/76 neurons) or SB431542 plus TGF-β1 (33/106 neurons) was similar to that in control cultures (25/108), suggesting that SB431542 treatment does not affect basal TRPV1 sensitivity of DRG cells (Fig. 3B). In addition, we found that several DRG cells were highly responsive after TGF-β1 treatment; 11/79 (13.9%) cells showed a Δ[Ca2+]i >300 nm with 2/79 (2.5%) showing a Δ[Ca2+]i >450 nm after capsaicin treatment (Fig. 3C). In comparison, untreated DRG cells showed no cells, those pre-treated with SB431542 showed 3/23 (13.0%) cells, and SB431542 plus TGF-β1 showed 2/33 (6.1%) cells with Δ[Ca2+]i >300 nm after capsaicin activation (Fig. 3C). In general, the kinetics of calcium influx and efflux did not differ greatly between the treatments when averaged across all cells (Fig. 3D). Finally, to evaluate whether TGF-β1 treatment could regulate mRNA levels of TRPV1, we performed real-time RT-PCR using total RNA obtained from the DRG primary culture. We found that mRNA levels of TRPV1 remained unchanged in cultures treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) for 24 h when compared with untreated DRG cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

TGF-β1 increased TRPV1 phosphorylation resulting in increased intracellular Ca2+ influx in DRG primary culture. A, representative Western blots of phospho-Smad2, Smad2, p35, Cdk5, P-T407-TRPV1, and α-tubulin protein levels from the mouse DRG primary culture treated with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) or pre-treated with SB431542 (10 μm) for 1 h, and then with TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml) for 24 h. B, number of DRG neurons after each treatment that responded to 400 nm capsaicin, calculated as percentage of total within the field of view (see “Experimental Procedures”). Cultures treated with TGF-β1 showed more capsaicin-responsive DRG neurons. Data are plotted as mean ± S.D., compared using Student's t test. The TGF-β1 group is significantly different from all (p < 0.05). C, the peak change in intracellular calcium from baseline (average [Ca2+]i from 0 to 2 min) after capsaicin treatment. All capsaicin-responsive DRG neurons are plotted individually, bars represent mean ± S.D. There is no significant difference in the mean Δ[Ca2+]i between the treatments. D, traces for all capsaicin-responsive DRG neurons were averaged and plotted as a function of time. There are no dramatic differences in the kinetics of the calcium responses to capsaicin between treatment groups.

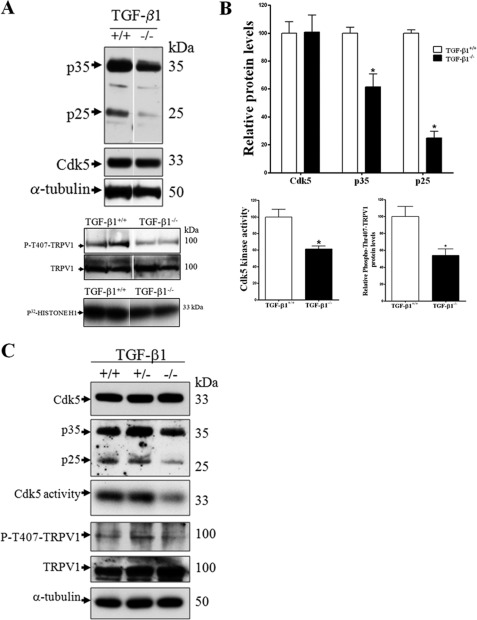

Decrease in Cdk5-mediated TRPV1 Phosphorylation in TG and DRG in Tgf-β1−/− Mice

We previously reported the generation and characterization of Tgf-β1−/− mice, which displayed multifocal inflammation at 2 weeks of age affecting many organs, leading to early lethality (29, 42). These findings, and many subsequent studies, suggested a critical role for TGF-β1 in immune regulation and resolution of inflammation (18, 29, 43). Because of the induction of Cdk5 activity by TGF-β1 treatment of B104 cells and DRG neuronal culture through direct regulation of p35 expression, we assessed whether deficiency of Tgf-β1 in the 14-day-old knock-out mice can regulate Cdk5 activity specifically in nociceptive tissue, TG and DRG. We found that Cdk5 protein levels remained unaltered in TG and DRG from Tgf-β1−/− mice as compared with control mice (Fig. 4, A and C). However, p35 protein levels and p25, a cleaved fragment of p35, were significantly reduced in TG and DRG from Tgf-β1−/− mice, as compared with control mice (Fig. 4, A–C). Cdk5 kinase activity was also significantly decreased in TG and DRG (Fig. 4, A–C). Most importantly, we found that decreased Cdk5 activity resulted in decreased phosphorylation of TRPV1 at Thr-407 (Fig. 4, A–C).

FIGURE 4.

TG and DRG from 2-week-old TGF-β1−/− mice show a decrease in Cdk5 kinase activity and Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 at Thr-407. A, representative Western blots of Cdk5, p35, and p25 protein levels and Cdk5 kinase activity and P-T407-TRPV1 in TG from 2-week-old old TGF-β1−/− mice. B, quantification of Cdk5, p35, and p25 protein levels and Cdk5 kinase activity and phospho-T407-TRPV1 in TG from TGF-β1−/− mice. The bars represent mean ± S.E. n = 4–6, *, p < 0.05 as compared with TGF-β1+/+ mice (Student's t test). C, Western blot of a pool of DRGs from several mice shows Cdk5, p35, p25, Cdk5 kinase activity, P-T407-TRPV1 and TRPV1, and α-tubulin protein levels from TGF-β1+/+ (n = 6), TGF-β1+/− (n = 13), and TGF-β1−/− (n = 7) mice at 2 weeks old. The bars represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 as compared with TGF-β1+/+ or TGF-β1+/− mice (Student's t test).

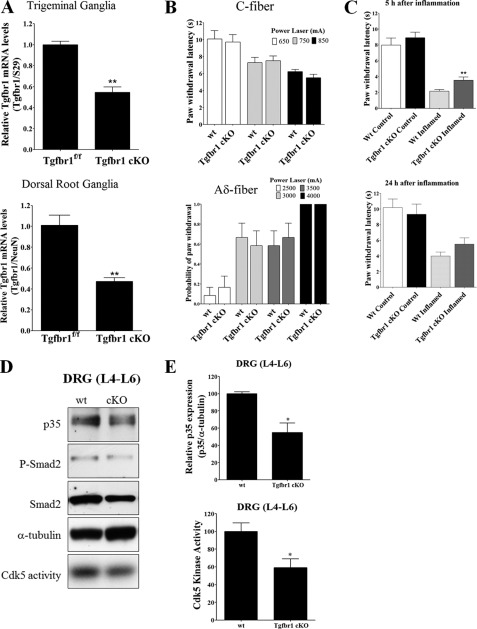

Decreased Cdk5 Activity and Attenuated Responses to Thermal Stimulation following Inflammation in Mice Deficient in TGF-β Signaling in Nociceptive Neurons

Due to the premature lethality associated with Tgf-β1−/− mice, we generated a Tgfbr1 conditional knock-out mouse (Tgfbr1 cKO) with decreased TGF-β signaling specifically in nociceptive neurons. We used a mouse line with Cre expression driven by the promoter of the sensory neuron-specific (SNS) voltage-gated sodium ion channel NaV1.8, which is specifically expressed in small-diameter sensory neurons in neonatal and adult DRG and TG (31). The NaV1.8-Cre line was mated with Tgfbr1f/f mice (30) to generate Tgfbr1 cKO mice. These mice were born with an expected Mendelian frequency and without any signs of inflammation as evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin staining in nociceptive tissues (TG and DRG) and in several primary organs such as heart, lung, liver, stomach, pancreas, thymus, and kidney from postnatal 45-day-old mice (data not shown). Conditional deletion of Tgfbr1 in DRG and TG was evaluated by real time RT-PCR for Tgfbr1 mRNA levels. We found that Tgfbr1 mRNA expression was decreased in TG and DRG from Tgfbr1 cKO mice as compared with control mice (Fig. 5A). Despite the decrease in Tgfbr1 mRNA expression in TG and DRG from Tgfbr1 cKO mice, basal signaling through the TGF-β pathway was only slightly decreased as assessed by Western blots for phospho-Smad2 (data not shown). This is likely attributable to the heterogeneous neuronal populations in whole TG and DRG. The neurons in which Tgfbr1 was conditionally deleted (small-diameter sensory neurons) represent only 34–36% of the entire set of DRG neurons (31), whereas the remaining subpopulations serve other sensory modalities (proprioception, light touch, warm temperature, etc.). Furthermore, we evaluated whether deletion of Tgfbr1 results in deregulation of Cdk5 activity. We could not detect any change in both p35 and Cdk5 protein levels in DRG and TG, as well as in Cdk5 activity in TG and DRG from postnatal 45-day-old Tgfbr1 cKO compare with control mice (data not shown). To evaluate whether pain sensation was affected in Tgfbr1 cKO mice, acute nociceptive responses were measured using an infrared diode laser to activate cutaneous thermal nociceptive nerve endings (33) in the hind paws of Tgfbr1 cKO mice between 1 and 2 months of age, who showed no signs of inflammation or body weight loss. Using a long pulse for slow-rate cutaneous heating (C-fiber), we observed no significant difference in paw withdrawal latency among Tgfbr1 cKO and WT mice (Fig. 5B). Similarly, when hind paws were stimulated using a high-energy short laser pulse, with a high-rate of cutaneous heating (Aδ-fibers), the probability of eliciting a withdrawal response was not changed in Tgfbr1 cKO as compared with control mice (Fig. 5B). Because TGF-β signaling is deregulated during inflammatory pain (44, 45), we assessed whether thermal pain response in Tgfbr1 cKO mice are affected after experimental inflammation induced by intraplantar carrageenan injection. We injected carrageenan into the left and vehicle into the right hind paws of 1-month-old Tgfbr1 cKO and control mice, and then we measured paw withdrawal latency at 5 and 24 h after injection. As expected, withdrawal latencies were significantly diminished in all carrageenan-injected paws at 5 and 24 h (Fig. 5C) due to robust inflammation and hyperalgesia. Most importantly, however, withdrawal latencies from the inflamed paws of Tgfr1 cKO mice were significantly increased (i.e. they were less hyperalgesic) when compared with control mice at 5 h, but this effect was only partially sustained at 24 h after carrageenan injection. This suggests that deletion of Tgfbr1 results in a phenotype that shows less nociceptive activity following the onset of inflammation and that this effect tapers off as the inflammation progresses (Fig. 5C). Next, we evaluated possible changes in p35 protein levels and Cdk5 activity in DRGs from 1-month-old Tgfbr1 cKO mice after 5 h of bilateral carrageenan inflammation in both hind paws. Remarkably, p35 protein levels were significantly decreased in lumbar 4 to 6 DRGs (L4–L6) of Tgfbr1 cKO as compared with control mice (Fig. 5, D and E). Likewise, Cdk5 kinase activity was also significantly decreased in DRGs of Tgfbr1 cKO mice injected with carrageenan (Fig. 5, D and E). Taken together, these results suggest that deletion of Tgfbr1 results in a reduction in p35 protein levels and a consequent decrease in Cdk5 kinase activity in sensory neurons; in combination with inflammation, this produces a further decrease, but not a complete loss of Cdk5 activity, resulting in attenuation of hyperalgesia in Tgfbr1 cKO mice.

FIGURE 5.

Decreased Cdk5 activity and attenuated responses to thermal stimulation after induced inflammation in TGF-β receptor I conditional knock-out mice (SNS-Cre; Tgfbr1f/f), which affects TGF-β signaling specifically in TG and DRG. A, specific deletion of Tgfbr1 in TG and DRG was measured by real-time RT-PCR from RNA isolated from TG and DRG of Tgfbr1 cKO and control mice. B, 1–2-month-old Tgfbr1 cKO and WT mice were evaluated behaviorally with thermal stimulation. C- and Aδ-fiber responses were measured using a variable power infrared diode laser. To stimulate C-fibers, we used long pulses of low intensity (650, 750, and 850 mA) and to stimulate Aδ-fibers we used short pulses of high intensity (2500, 3000, 3500, and 4000 mA). C, 1-month-old Tgfbr1 cKO and WT mice were evaluated with thermal stimulation after carrageenan-induced hind paw inflammation. The left hind paw was injected with 2% carrageenan in saline and the right hind paw was injected with saline only. C-fiber stimulation was measured (650 mA) at 5 and 24 h after injection. D, representative Western blots of p35, phospho-Smad2, and Smad2 protein levels, plus Cdk5 kinase activity in L4–L6 DRGs from Tgfbr1 cKO and control mice 5 h after carrageenan-induced inflammation. E, quantification of p35 protein levels and Cdk5 kinase activity in DRGs L4–L6 from Tgfbr1 cKO and control mice. The bars represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (Student's t test).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated cross-talk between two important signaling pathways involved in inflammation and how this cross-talk could affect nociceptive signaling. Our investigations demonstrate that in rat neuroblastoma B104 cells, TGF-β1 treatment increased Cdk5 and p35 protein levels with a concomitant increase in Cdk5 activity. Notably, we found TGF-β1 treatment increased Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 and increased capsaicin-induced calcium influx in primary DRG neuronal cultures. We also report here that Cdk5 activity was decreased in TG and DRG of Tgf-β1−/− mice, resulting in decreased Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 in DRG. We confirmed these findings in Tgfbr1 cKO mice (SNS-Cre; Tgfbr1f/f) and again observed decreased Cdk5 activity in TG and DRG with attenuated thermal hyperalgesia after peripheral inflammation. Thus, our results indicate that an active cross-talk between the TGF-β and Cdk5 pathways directly influences pain signaling.

We and others have demonstrated that Cdk5 plays an important role in pain signaling (7–14). Previously, we discovered that p35 knock-out mice exhibit significantly decreased Cdk5 activity and show delayed responses to acute noxious thermal stimulation as compared with control mice. In contrast, mice overexpressing p35 exhibit elevated levels of Cdk5 activity and are more sensitive to noxious thermal stimuli than controls. Furthermore, carrageenan-induced (7) or complete Freund's adjuvant-induced (8) inflammation of the mouse hind paw caused increased Cdk5 activity in DRG with a concomitant increase in the phosphorylation of TRPV1 at Thr-407 (10). In addition, we determined that TNF-α is a major regulator of p35 expression during inflammation, thereby directly affecting Cdk5 activity (11, 12). Recent evidence has shown that TGF-β1 is also involved in pain signaling, but the detailed molecular mechanisms are not fully understood (25–27, 44–46). In addition to TGF-β1 activation of canonical Smad pathways, recent reports have shown that TGF-β1 also induces other (no canonical) pathways, including the RhoA and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, the latter include extracellular signal-regulated kinases, ERK1/2 (38, 47). The ERK1/2 signaling pathway is a major regulator of Cdk5 activity through control of Egr-1 and p35 expression (11, 41). For these reasons, we chose to evaluate whether TGF-β1 can directly induce Cdk5 activity through sustained and robust expression of p35, thereby suggesting a novel molecular mechanism.

Previously, we found that another cytokine, TNF-α, increased Cdk5 activity through activation of the ERK1/2-Egr-1-p35 signaling pathway in PC12 cells (11). However, the PC12 cells only express low levels of Tgfbr2 and do not respond to TGF-β (37). To evaluate whether TGF-β1 can regulate Cdk5 kinase activity, we used rat B104 neuroblastoma cells as a model of developing neurons that respond to TGF-β1 (39). TGF-β1 also regulates the ERK1/2 signaling pathway and gene expression in these cells (38, 39). Our results show that B104 cells express Cdk5 and p35 protein, and also display Cdk5 kinase activity. Most importantly, we report here that TGF-β1 treatment significantly increases p35 promoter activity. In addition, we found that the TGF-β1 induced an increase of phospho-ERK1/2, and increased Egr-1 and p35 mRNA expression levels, with a subsequent increase of p35 protein levels resulting in an increase of Cdk5 kinase activity. We also noticed that Egr-1 mRNA peaks at about 1 h and returned to basal level at 6 h after TGF-β treatment, whereas the p35 protein level remained higher at 24 h following the treatment. This lag could be attributed to complex transcriptional regulation of Egr-1 and its involvement in multiple transduction cascades (48). However, the functional significance of TGF-β action was reinforced by our observation that the TGF-β1 inhibitor (SB431542) significantly blocked the TGF-β1-mediated increase of Cdk5 kinase activity. Likewise, MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 alone, or in combination with TGF-β1, significantly decreased Cdk5 kinase activity, suggesting that the ERK1/2 signaling pathway is a key pathway mediating the cross-talk between TGF-β1 and Cdk5 kinase pathways. Together these results show that TGF-β1 directly activates ERK1/2 leading to an increase in Egr-1 expression and subsequent elevation of p35 expression. This results in an increase in Cdk5 kinase activity.

We also found that Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 was regulated by TGF-β1 in DRG primary cultures. Treatment with TGF-β1 increased, whereas treatment with SB431542 decreased the phosphorylation of TRPV1 in DRG cultures. This phosphorylation of TRPV1 has a functional consequence, because treatment with TGF-β1 increased the number of DRG neurons responding to capsaicin. In contrast, treatment with SB431542 blocked the TGF-β1 effect, suggesting that the TGF-β1 signaling pathway needs to be active to sensitize DRG neurons. It is likely, however, that TGF-β1 directly regulates TRPV1 through post-translational mechanisms in these cells, possibly via regulation of Cdk5 activity because TRPV1 mRNA levels remain unchanged in DRG cultures treated with TGF-β1. Although some cells appear hyper-responsive after TGF-β1 treatment in our experiment, the largest observed affect was an increase in the overall number of cells responding to capsaicin. This suggests that Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 could regulate trafficking of TRPV1 to the membrane. But location of the Cdk5 phosphorylation site on the N-terminal region of TRPV1 also suggests it may regulate protein-protein interactions that influence TRPV1 activity. Collectively, these observations point toward a role for TGF-β1 in the development of inflammation-induced hyperalgesia through direct regulation of Cdk5 activity and Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1.

TGF-β has been implicated in pain signaling but its precise role is not completely clear. For instance, TGF-β family members negatively modulate pain perception, specifically in mouse models for neuropathic pain (26, 27). Furthermore, TGF-β1 treatment attenuated neuropathic pain (26), and also, TGF-β family members were implicated in the modulation of chronic and acute pain perception through the regulation of genes encoding endogenous opioids (27). Also, protein levels of TGF-β1 are significantly increased in the plasma (25) and cerebrospinal fluid (46) of patients with migraines. To evaluate in vivo the role of TGF-β1 in nociceptive processes and its involvement in the regulation of Cdk5 activity, we removed TG and DRG from the Tgf-β1−/− mice and assessed the p35 expression levels and Cdk5 kinase activity in those tissues. A lack of TGF-β1 resulted in decreased p35 protein levels in TG and DRG, along with a decrease in Cdk5 activity. Most importantly, we found a parallel decrease in Cdk5 activity and Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1 in TG and DRG from Tgf-β1−/− mice. To circumvent systemic inflammation associated with TGF-β1−/− mice, we generated cKO mice that specifically lack Tgfbr1 in a subpopulation of nociceptive primary afferents of the TG and DRG and evaluated whether a blunted TGF-β signaling pathway could affect Cdk5 activity and pain sensation. Interestingly, we found a decrease in Cdk5 kinase activity and an associated attenuation of behavioral response to thermal stimulation following inflammation in Tgfbr1 cKO mice, corroborating our observations in Tgf-β1−/− mice. Taken together, these results identify a novel molecular mechanism based on cross-talk between TGF-β1 and Cdk5 that appears to contribute to the sensitization of nociceptive signaling.

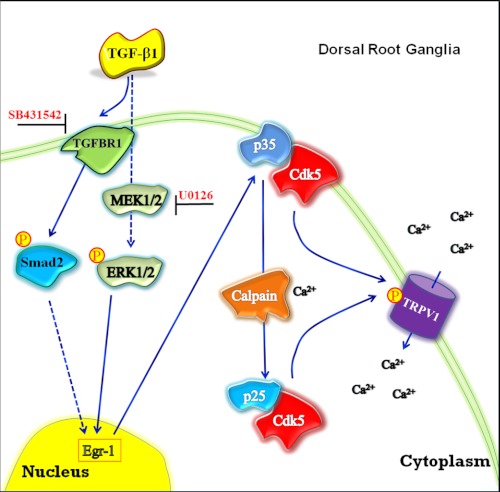

It was reported earlier that TGF-β1, among other members of this family, could be negatively modulating pain perception (26, 27). In contrast, our results on Tgf-β1−/− mice are consistent with a positive modulation of pain signaling by TGF-β1. It should be noted that the Cdk5 kinase activity was unchanged in the spinal cords of Tgf-β1−/− mice (data not shown), suggesting that TGF-β1 may play dual roles in different types of persistent pain conditions. At the level of the nociceptive primary afferent neuron, TGF-β may negatively modulate sensitivity by a Cdk5-independent mechanism in neuropathic nerve injury models, and modulate it positively by a Cdk5-dependent mechanism in peripheral inflammation (as examined in this report). In support of our proposal that TGF-β1 plays a positive role in inflammation-induced hyperalgesia, activin A, another member of the TGF-β family, is released during peripheral inflammation. This increases the expression of the calcitonin gene-related peptide and pain sensation (49). In addition, it was found that activin A mediates hyperalgesia through a mechanism involving acute sensitization of TRPV1 (50). Basal responses to Aδ-fiber and C-fiber stimulation were not changed in Tgfbr1 cKO mice, but after the induction of inflammation with carrageenan we found decreased hyperalgesia at 5 h but not at 24 h after injection, suggesting that deletion of Tgfbr1 in DRG produced a temporally discrete phenotype characterized by reduced nociceptive transmission following the onset of inflammation. As the inflammation progresses, multiple parallel processes are engaged that lead to pain sensitization but are independent of TGF-β1-mediated Cdk5 activity in peripheral afferents. In conclusion, we have shown that an active cross-talk exists between TGF-β and Cdk5 in primary sensory neurons and affects nociceptive signaling during inflammation (Fig. 6). Thus, TGF-β activates Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways, which could regulate ERK1/2 activity and in turn induce Egr-1 expression. This results in elevated levels of Cdk5 and p35 mRNA and proteins, as well as a concomitant increase in Cdk5 activity leading to an increase in Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1. When DRG neurons are sensitized or activated, the increased intracellular Ca2+ could also regulate calpain activity, which could generate more p25, resulting in a stronger induction of Cdk5 activity. Similarly, a lack of TGF-β1 or Tgfbr1 decreased p35 protein expression, which in turn decreases Cdk5 activity. Subsequently, we found an associated decrease in Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1. Our in vitro finding suggests that Cdk5 phosphorylation increases the amount of active TRPV1 in the membrane of DRG neurons. We believe our findings on the active cross-talk between Cdk5 and TGF-β pathways in primary afferents and the influence of the cross-talk on nociceptive processing will enhance our understanding of the complex nature of inflammatory pain transduction and primary afferent sensitization.

FIGURE 6.

A proposed model of TGF-β1-mediated regulation of Cdk5 kinase activity. TGF-β1 up-regulates Cdk5 activity through canonical Smad-dependent pathway and noncanonical ERK1/2 pathway, which can be blocked by SB431542 or U0126, respectively. Activation of these pathways induces p35 protein expression through induction of Egr-1, resulting in increased Cdk5 kinase activity. In addition, it increases Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of TRPV1, ultimately leading to increased intracellular Ca2+ influx in a subpopulation of nociceptive primary sensory neurons. Moreover, increased intracellular Ca2+ levels up-regulate calpain activity resulting in the production of p25, which leads to a further increase in Cdk5 kinase activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bradford Hall and Zhijun Sun for critical reading of the manuscript, Alfredo Molinolo for analysis of stained section of Tgfr1 cKO mice, and Shelagh Johnson for expert editorial assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health Division of Intramural Research, NIDCR.

- Cdk5

- cyclin-dependent kinase 5

- TRPV1

- transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- DRG

- dorsal root ganglia

- TG

- trigeminal ganglia

- SNS

- sensory neuron specific.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dhavan R., Tsai L. H. (2001) A decade of CDK5. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dhariwala F. A., Rajadhyaksha M. S. (2008) An unusual member of the Cdk family, Cdk5. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 28, 351–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohshima T., Ward J. M., Huh C. G., Longenecker G., Veeranna, Pant H. C., Brady R. O., Martin L. J., Kulkarni A. B. (1996) Targeted disruption of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 gene results in abnormal corticogenesis, neuronal pathology and perinatal death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11173–11178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ko J., Humbert S., Bronson R. T., Takahashi S., Kulkarni A. B., Li E., Tsai L. H. (2001) p35 and p39 are essential for cyclin-dependent kinase 5 function during neurodevelopment. J. Neurosci. 21, 6758–6771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanaka T., Veeranna, Ohshima T., Rajan P., Amin N. D., Cho A., Sreenath T., Pant H. C., Brady R. O., Kulkarni A. B. (2001) Neuronal cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activity is critical for survival. J. Neurosci. 21, 550–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li B. S., Zhang L., Takahashi S., Ma W., Jaffe H., Kulkarni A. B., Pant H. C. (2002) Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 prevents neuronal apoptosis by negative regulation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3. EMBO J. 21, 324–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pareek T. K., Keller J., Kesavapany S., Pant H. C., Iadarola M. J., Brady R. O., Kulkarni A. B. (2006) Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activity regulates pain signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang Y. R., He Y., Zhang Y., Li Y., Li Y., Han Y., Zhu H., Wang Y. (2007) Activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) in primary sensory and dorsal horn neurons by peripheral inflammation contributes to heat hyperalgesia. Pain 127, 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pareek T. K., Kulkarni A. B. (2006) Cdk5, a new player in pain signaling. Cell Cycle 5, 585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pareek T. K., Keller J., Kesavapany S., Agarwal N., Kuner R., Pant H. C., Iadarola M. J., Brady R. O., Kulkarni A. B. (2007) Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 modulates nociceptive signaling through direct phosphorylation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 660–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Utreras E., Futatsugi A., Rudrabhatla P., Keller J., Iadarola M. J., Pant H. C., Kulkarni A. B. (2009) Tumor necrosis factor-α regulates cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activity during pain signaling through transcriptional activation of p35. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2275–2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Utreras E., Futatsugi A., Pareek T. K., Kulkarni A. B. (2009) Molecular roles of Cdk5 in pain signaling. Drug Discov. Today Ther. Strateg. 6, 105–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Utreras E., Terse A., Keller J., Iadarola M. J., Kulkarni A. B. (2011) Resveratrol inhibits Cdk5 activity through regulation of p35 expression. Mol. Pain 7, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xie W. Y., He Y., Yang Y. R., Li Y. F., Kang K., Xing B. M., Wang Y. (2009) Disruption of Cdk5-associated phosphorylation of residue threonine 161 of the δ-opioid receptor. Impaired receptor function and attenuated morphine antinociceptive tolerance. J. Neurosci. 29, 3551–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Massagué J. (1990) The transforming growth factor-β family. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 6, 597–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shull M. M., Ormsby I., Kier A. B., Pawlowski S., Diebold R. J., Yin M., Allen R., Sidman C., Proetzel G., Calvin D. (1992) Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359, 693–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kulkarni A. B., Huh C. G., Becker D., Geiser A., Lyght M., Flanders K. C., Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Ward J. M., Karlsson S. (1993) Transforming growth factor β1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 770–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kulkarni A. B., Ward J. M., Yaswen L., Mackall C. L., Bauer S. R., Huh C. G., Gress R. E., Karlsson S. (1995) Transforming growth factor-β1 null mice. An animal model for inflammatory disorders. Am. J. Pathol. 146, 264–275 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wyss-Coray T. (2006) TGF-β pathway as a potential target in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 3, 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brionne T. C., Tesseur I., Masliah E., Wyss-Coray T. (2003) Loss of TGF-β1 leads to increased neuronal cell death and microgliosis in mouse brain. Neuron 40, 1133–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Makwana M., Jones L. L., Cuthill D., Heuer H., Bohatschek M., Hristova M., Friedrichsen S., Ormsby I., Bueringer D., Koppius A., Bauer K., Doetschman T., Raivich G. (2007) Endogenous transforming growth factor β1 suppresses inflammation and promotes survival in adult CNS. J. Neurosci. 27, 11201–11213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tesseur I., Zou K., Esposito L., Bard F., Berber E., Can J. V., Lin A. H., Crews L., Tremblay P., Mathews P., Mucke L., Masliah E., Wyss-Coray T. (2006) Deficiency in neuronal TGF-β signaling promotes neurodegeneration and Alzheimer pathology. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3060–3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grammas P., Ovase R. (2002) Cerebrovascular transforming growth factor-β contributes to inflammation in the Alzheimer disease brain. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 1583–1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wyss-Coray T., Feng L., Masliah E., Ruppe M. D., Lee H. S., Toggas S. M., Rockenstein E. M., Mucke L. (1995) Increased central nervous system production of extracellular matrix components and development of hydrocephalus in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor-β1. Am. J. Pathol. 147, 53–67 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishizaki K., Takeshima T., Fukuhara Y., Araki H., Nakaso K., Kusumi M., Nakashima K. (2005) Increased plasma transforming growth factor-β1 in migraine. Headache 45, 1224–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Echeverry S., Shi X. Q., Haw A., Liu H., Zhang Z. W., Zhang J. (2009) Transforming growth factor-β1 impairs neuropathic pain through pleiotropic effects. Mol. Pain 5, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tramullas M., Lantero A., Díaz A., Morchón N., Merino D., Villar A., Buscher D., Merino R., Hurlé J. M., Izpisúa-Belmonte J. C., Hurlé M. A. (2010) BAMBI (bone morphogenetic protein and activin membrane-bound inhibitor) reveals the involvement of the transforming growth factor-β family in pain modulation. J. Neurosci. 30, 1502–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kulkarni A. B., Karlsson S. (1993) Transforming growth factor-β1 knockout mice. A mutation in one cytokine gene causes a dramatic inflammatory disease. Am. J. Pathol. 143, 3–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Larsson J., Goumans M. J., Sjöstrand L. J., van Rooijen M. A., Ward D., Levéen P., Xu X., ten Dijke P., Mummery C. L., Karlsson S. (2001) Abnormal angiogenesis but intact hematopoietic potential in TGF-β type I receptor-deficient mice. EMBO J. 20, 1663–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Agarwal N., Offermanns S., Kuner R. (2004) Conditional gene deletion in primary nociceptive neurons of trigeminal ganglia and dorsal root ganglia. Genesis 38, 122–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cuellar J. M., Manering N. A., Klukinov M., Nemenov M. I., Yeomans D. C. (2010) Thermal nociceptive properties of trigeminal afferent neurons in rats. Mol. Pain 6, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitchell K., Bates B. D., Keller J. M., Lopez M., Scholl L., Navarro J., Madian N., Haspel G., Nemenov M. I., Iadarola M. J. (2010) Ablation of rat TRPV1-expressing Aδ/C-fibers with resiniferatoxin. Analysis of withdrawal behaviors, recovery of function and molecular correlates. Mol. Pain 6, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iadarola M. J., Brady L. S., Draisci G., Dubner R. (1988) Enhancement of dynorphin gene expression in spinal cord following experimental inflammation. Stimulus specificity, behavioral parameters, and opioid receptor binding. Pain 35, 313–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fan R. J., Shyu B. C., Hsiao S. (1995) Analysis of nocifensive behavior induced in rats by CO2 laser pulse stimulation. Physiol. Behav. 57, 1131–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Takahashi S., Ohshima T., Cho A., Sreenath T., Iadarola M. J., Pant H. C., Kim Y., Nairn A. C., Brady R. O., Greengard P., Kulkarni A. B. (2005) Increased activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 leads to attenuation of cocaine-mediated dopamine signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1737–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lutz M., Krieglstein K., Schmitt S., ten Dijke P., Sebald W., Wizenmann A., Knaus P. (2004) Nerve growth factor mediates activation of the Smad pathway in PC12 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 920–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Luo J., Miller M. W. (1999) Transforming growth factor β1-regulated cell proliferation and expression of neural cell adhesion molecule in B104 neuroblastoma cells. Differential effects of ethanol. J. Neurochem. 72, 2286–2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller M. W., Mooney S. M., Middleton F. A. (2006) Transforming growth factor β1 and ethanol affect transcription and translation of genes and proteins for cell adhesion molecules in B104 neuroblastoma cells. J. Neurochem. 97, 1182–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bottenstein J. E., Sato G. H. (1979) Growth of a rat neuroblastoma cell line in serum-free supplemented medium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 514–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harada T., Morooka T., Ogawa S., Nishida E. (2001) ERK induces p35, a neuron-specific activator of Cdk5, through induction of Egr1. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 453–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kulkarni A. B., Thyagarajan T., Letterio J. J. (2002) Function of cytokines within the TGF-β superfamily as determined from transgenic and gene knockout studies in mice. Curr Mol. Med. 2, 303–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wahl S. M., Chen W. (2005) Transforming growth factor-β-induced regulatory T cells referee inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 7, 62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ronaldson P. T., Finch J. D., Demarco K. M., Quigley C. E., Davis T. P. (2011) Inflammatory pain signals an increase in functional expression of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1a4 at the blood-brain barrier. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 336, 827–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ronaldson P. T., Demarco K. M., Sanchez-Covarrubias L., Solinsky C. M., Davis T. P. (2009) Transforming growth factor-β signaling alters substrate permeability and tight junction protein expression at the blood-brain barrier during inflammatory pain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 29, 1084–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bø S. H., Davidsen E. M., Gulbrandsen P., Dietrichs E., Bovim G., Stovner L. J., White L. R. (2009) Cerebrospinal fluid cytokine levels in migraine, tension-type headache and cervicogenic headache. Cephalalgia 29, 365–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Habashi J. P., Doyle J. J., Holm T. M., Aziz H., Schoenhoff F., Bedja D., Chen Y., Modiri A. N., Judge D. P., Dietz H. C. (2011) Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm in mice through ERK antagonism. Science 332, 361–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pagel J. I., Deindl E. (2011) Early growth response 1, a transcription factor in the cross-fire of signal transduction cascades. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 48, 226–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu P., Van Slambrouck C., Berti-Mattera L., Hall A. K. (2005) Activin induces tactile allodynia and increases calcitonin gene-related peptide after peripheral inflammation. J. Neurosci. 25, 9227–9235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhu W., Xu P., Cuascut F. X., Hall A. K., Oxford G. S. (2007) Activin acutely sensitizes dorsal root ganglion neurons and induces hyperalgesia via PKC-mediated potentiation of transient receptor potential vanilloid I. J. Neurosci. 27, 13770–13780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]