Background: Choline phosphorylation is the first step of phosphatidylcholine synthesis.

Results: Toxoplasma gondii expresses a novel choline kinase forming cytosolic clusters. Its conditional mutagenesis identifies a cryptic exon-promoter. Besides, the parasite mutant displays a normal growth despite a substantial depletion of PtdCho.

Conclusion: Plasticity of gene expression and membrane biogenesis are revealed.

Significance: Adaptation of an intracellular pathogen to metabolic perturbations and disparate host cells can thus be ensured.

Keywords: Membrane Biogenesis, Parasite Metabolism, Phosphatidylcholine, Phosphatidylethanolamine, Phospholipid, Choline Kinase, Cryptic Promoter, Toxoplasma gondii

Abstract

The obligate intracellular and promiscuous protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii needs an extensive membrane biogenesis that must be satisfied irrespective of its host-cell milieu. We show that the synthesis of the major lipid in T. gondii, phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho), is initiated by a novel choline kinase (TgCK). Full-length (∼70-kDa) TgCK displayed a low affinity for choline (Km ∼0.77 mm) and harbors a unique N-terminal hydrophobic peptide that is required for the formation of enzyme oligomers in the parasite cytosol but not for activity. Conditional mutagenesis of the TgCK gene in T. gondii attenuated the protein level by ∼60%, which was abolished in the off state of the mutant (Δtgcki). Unexpectedly, the mutant was not impaired in its growth and exhibited a normal PtdCho biogenesis. The parasite compensated for the loss of full-length TgCK by two potential 53- and 44-kDa isoforms expressed through a cryptic promoter identified within exon 1. TgCK-Exon1 alone was sufficient in driving the expression of GFP in E. coli. The presence of a cryptic promoter correlated with the persistent enzyme activity, PtdCho synthesis, and susceptibility of T. gondii to a choline analog, dimethylethanolamine. Quite notably, the mutant displayed a regular growth in the off state despite a 35% decline in PtdCho content and lipid synthesis, suggesting a compositional flexibility in the membranes of the parasite. The observed plasticity of gene expression and membrane biogenesis can ensure a faithful replication and adaptation of T. gondii in disparate host or nutrient environments.

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii causes toxoplasmosis, which affects immuno-deficient patients and neonates. Toxoplasma is an obligate intracellular parasite of the phylum Apicomplexa, which, unlike its peers and other intracellular pathogens, has an exceptional ability to replicate in virtually any nucleated vertebrate host cell (1). The plasticity of biomass production and associated metabolic pathways is necessary to comprehend the evolution of T. gondii as a promiscuous pathogen. In this regard, we and others have shown the flexibility in the nucleotide (2, 3) and central carbon metabolism (4) of T. gondii. Successful replication of T. gondii within the parasitophorous vacuole also requires substantial biogenesis of subcellular membranes. The T. gondii membranes consist primarily of phospholipids and neutral lipids and minor plant-like lipids (5, 6). Phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho)2 is the most abundant lipid in T. gondii, accounting for ∼75% of total phospholipids (7). Whether T. gondii meets demand for PtdCho by de novo synthesis and/or by salvage from the host cell is not known.

The mammalian PtdCho synthesis can occur via two pathways (8): the Kennedy (CDP-choline) pathway and the sequential methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) (supplemental Fig. S1). PtdEtn is derived from the CDP-ethanolamine pathway or by decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) (8). The CDP-choline route is initiated by the action of a choline kinase phosphorylating choline to phosphocholine. Subsequent catalysis by phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase and choline-phosphotransferase completes the PtdCho synthesis (8, 9). Unlike its mammalian host (8), Toxoplasma does not possess activity for a PtdEtn methyltransferase and thus appears incompetent in making PtdCho from PtdEtn (7). We and others have shown that T. gondii can incorporate the lipid precursors, choline, ethanolamine, and serine into PtdCho, PtdEtn, and PtdSer, respectively (7, 10). Also, a choline analog, dimethylethanolamine (DME), disrupted the parasite growth with an accumulation of PtdDME and a concurrent decline in PtdCho biogenesis (7, supplemental Fig. S1), which indicated a dependence of T. gondii on its endogenous CDP-choline route but requires a genetic validation. The target of this pharmacological inhibition has also not been established yet.

Here, we reveal an unprecedented resilience and plasticity of gene expression and membrane biogenesis in T. gondii. Moreover, the novel biochemical features of choline kinase such as its low affinity, cytosolic clusters, and stringent regulation render the CDP-choline route in T. gondii susceptible to analog inhibition and offer an excellent therapeutic target to arrest parasite growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Biological Resources

Cell culture reagents were purchased from Biotherm and PAA Laboratories. The radioactive chemicals were procured from PerkinElmer Life Sciences and American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Choline chloride and ethanolamine chloride were purchased from AppliChem. Silica gel plates for thin layer chromatography (TLC) were purchased from Merck. The mouse anti-His6 tag monoclonal antibody IgG1 was obtained from Dianova. Cloning reagents and the primary (anti-HA, anti-Myc) and secondary (Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 594) antibodies were purchased from Sigma and Invitrogen. The Escherichia coli Rosetta strain was obtained from Novagen. The anti-TgActin and anti-TgGap45 and anti-Ty1 antibodies were kind gifts from Dominique Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva, Switzerland) and Keith Gull (University of Oxford, UK). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant (KS106) was a generous donation by George Carman (Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ). The pTKO and p2854 vectors were kind donations of John Boothroyd (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA) and Dominique Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva, Switzerland).

Cell Culture, Molecular Cloning, and Quantitative PCR

Primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mm glutamine, minimum Eagle's medium nonessential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and grown at 37 °C at 10% CO2. All strains of T. gondii tachyzoites were maintained by serial passage in HFF monolayers. The mRNA was isolated from fresh syringe-released tachyzoites and transcribed into first-strand cDNA using the μMACS mRNA isolation and the cDNA synthesis kits (Miltenyi Biotec). TgCK and TgEK were amplified using PfuUltra II Fusion polymerase (Stratagene) and the indicated cDNA-specific primers (supplemental Table S1). For qPCR analysis, 100 ng RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA (SuperScript III first-strand synthesis SuperMix for quantitative RT-PCR, Invitrogen) and subjected to real-time PCR (SuperScript III Platinum SYBR Green one-step quantitative RT-PCR kit with ROX). The primers used for qPCR are indicated in supplemental Table S1.

Protein Expression in Escherichia coli and S. cerevisiae

The wild-type TgCK and TgEK proteins with a C-terminal histidine tag (TgCK-His6, TgEK-His6) and a truncated TgCK lacking first 20 residues with an N-terminal histidine tag (His6-TgCKS) were cloned in the pET22b+(TgCK-His6) or the pET28b+(TgEK-His6, His6-TgCKS) plasmids (primers in supplemental Table S1) and expressed in the E. coli Rosetta strain. The cultures were grown at 37 °C until an A600 of 0.3–0.5 was reached and induced with 1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 4 h at 25 °C. TgEK-His6, TgCK-His6, and His6-TgCKS proteins were purified by affinity chromatography on the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen) using 20 mm NaH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 500 mm NaCl, and 100 mm imidazole. The S. cerevisiae KS106 (MATα leu2-3 112, trp1-1 can1-100 ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15 eki1Δ::TRP1 cki1Δ::HIS3) (11) was grown in synthetic or yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium with 2% glucose at 30 °C. Choline and ethanolamine kinases (ScCK1, YLR133W; ScEK1, YDR147W, supplemental Table S1) were cloned into the galactose-inducible pESC-Ura vector and used as controls. The transformed strains were selected in the uracil-dropout medium with 2% glucose using standard yeast techniques.

Radioactive and Photometric Enzyme Assays

Choline kinase activity was determined by measuring the formation of [3H]phosphocholine from [3H]choline (3.125 nCi/nmol, 0–3.2 mm) in 67 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.5) containing 10 mm ATP, 11 mm MgCl2, 1.3 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) in a total volume of 60 μl. The substrate was removed from the radiolabeled phosphocholine by precipitation as choline reineckate (12) followed by TLC on Silica Gel 60 plates using 95% ethanol and 2% ammonium hydroxide (1:1). A similar assay was performed with [3H]ethanolamine and tested by TLC without precipitation. Choline kinase was also assayed by photometry adapted from a pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase-coupled system (13). The 200-μl reaction mixture in a 96-well plate contained the indicated amounts of choline, 100 mm Tris-Cl (pH 8.5), 100 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm NADH, 5 mm ATP, 1 mm phosphoenol-pyruvate, pyruvate kinase (30 units), lactate dehydrogenase (37 units), and 1–2 μg of protein. The data were fitted using robust fit nonlinear regression (GraphPad Prism v5.0).

Indirect Immuno-fluorescence of T. gondii

The HA-, Ty1-, and Myc epitope-tagged TgCK or TgEK constructs were made in pTKO or pNTP3 plasmids (supplemental Table S1). Extracellular tachyzoites (∼106, the hxgprt− or RH strain) were transfected with 50 μg of plasmid using the BTX630 instrument (2 kV, 50 ohms, 25 microfarads, 250 μs), and drug-selected for the HXGPRT (14) or DHFR-TS (15) selection markers. The parasite-infected HFF monolayers were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature followed by a 5-min neutralization in 0.1 m glycine/PBS. Cells were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS for 20 min, and nonspecific binding was blocked with 2% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Samples were stained with primary antibodies (anti-TgGap45 1:3000; anti-TgCK 1:200; anti-HA 1:1000; anti-Ty1 1:50; anti-Myc 1:1000 dilutions) followed by three washes with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. The secondary antibodies (mouse or rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594) were applied (1:3000), and after 3× PBS washes, samples were mounted in Fluoromount G for imaging (ApoTome, Carl Zeiss).

Immuno-gold Electron Microscopy

Toxoplasma-containing fibroblasts were first fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.25 m HEPES (pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature and then in 8% paraformaldehyde in the same buffer overnight at 4 °C. They were infiltrated, frozen, and sectioned as described (16). The sections were immuno-labeled with mouse anti-TgCK sera (1:250 in PBS, 1% fish skin gelatin) and then with anti-mouse IgG antibody followed by 10-nm protein A-conjugated gold particles (Utrecht University, Netherlands) before examination with a Philips CM120 electron microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) under 80 kV. For dual immuno-staining, the sections were labeled with mouse anti-TgCK sera and revealed by 10-nm protein A-gold particles. The rat anti-HA antibody (1:200) was detected by 5-nm protein A-gold particles.

Genetic Manipulation of TgCK Gene

The TgCK promoter was displaced using the tetracycline-regulatable promoter (pTetO7Sag4 (17)). Primers used for the genetic manipulation are depicted in supplemental Table S1. The 5′-UTR fragment (2 kb), amplified from tachyzoite gDNA using the primers (TgCK-PD-5′-UTR-F/R), was cloned into the pDT7S4 vector (18) at the NdeI site. The 1-kb region downstream to the initiating ATG of the TgCK gene was amplified (primers TgCK-PD-35′-UTR-F/R) and cloned at BglII and AvrII to achieve the promoter-displacement construct. The TaTi-Δku80 tachyzoites of T. gondii (∼106 11)) were transfected with 50 μg of the ApaI-linearized construct, and transgenic parasites were selected with 1 μm pyrimethamine (15). The resistant parasites were cloned by limiting dilution and screened for 5′- and 3′-crossover using TgCK-PD-5′Scr-F/DHFR-R or DHFR-F/TgCK-PD-3′Scr-R primers. The direct deletion of the TgCK locus was attempted using the p2854 construct with 3.3 kb of the 5′- and 3′-TgCK-UTRs (primers in supplemental Table S1).

Precursor Labeling and Lipid Analyses

Choline labeling (0.1 μCi/ml medium) of intracellular parasites was performed for 40 h in the parasitized HFF (multiplicity of infection = 3) cultures. Total lipids were extracted from PBS-washed axenic parasites according to Bligh and Dyer (19). Briefly, samples were suspended in 5.8 ml of CH3OH:H2O (2:0.9, v/v) followed by the addition of 2 ml of CHCl3, 1.8 ml of 0.2 m KCl, and 2 ml of CHCl3. The CHCl3 phase was backwashed two times with CH3OH:KCl (0.2 m):CHCl3 (1:0.9:0.1, v/v), dried under N2, and resuspended in 50–100 μl of CHCl3:CH3OH (9:1, v/v). Lipids were resolved on silica gel plates in CHCl3/CH3OH/H2O (65:25:4, v/v), visualized by iodine vapor or radiographic imaging, and identified by co-migration with standards.

RESULTS

TgCK and TgEK Encode Active Choline and Ethanolamine Kinases

To identify choline kinase(s), we searched the Toxoplasma database (ToxoDB) and performed alignments using orthologs from S. cerevisiae (ScCK1, YLR133W; ScEK1, YDR147W), Plasmodium falciparum (PfCK, PF14_0020; PfEK, PF11_0257), and Homo sapiens (HsCK, NP_001268.2; HsEK1, NP_061108.2). Our bioinformatic analysis showed two putative choline and/or ethanolamine kinases expressed in T. gondii (TGGT1_120660, TGGT1_040800). We cloned both ORFs using cDNA prepared from tachyzoite mRNA, which encodes TgCK and TgEK proteins with 630 and 547 residues, respectively (supplemental Figs. S2A and S3A). PCR amplification of the upstream flanking regions confirmed the presence of an in-frame stop codon before the initiating ATG in both kinases. TgCK and TgEK ORFs harbor a choline or ethanolamine kinase domain (PF01633) and a phosphotransferase motif. TgCK shows 19, 16, and 10% identity with HsCKα1, PfCK, and ScCK1 with best homology observed in the conserved regions (supplemental Fig. S2B). TgEK is 21, 20, and 14% identical to HsEK, PfEK, and ScEK1 proteins (supplemental Fig. S3B). Quite notably, TgCK possesses a peculiar N-terminal hydrophobic peptide (20 residues) with no homology to a known protein and stretches of amino acid insertions (supplemental Fig. S2A).

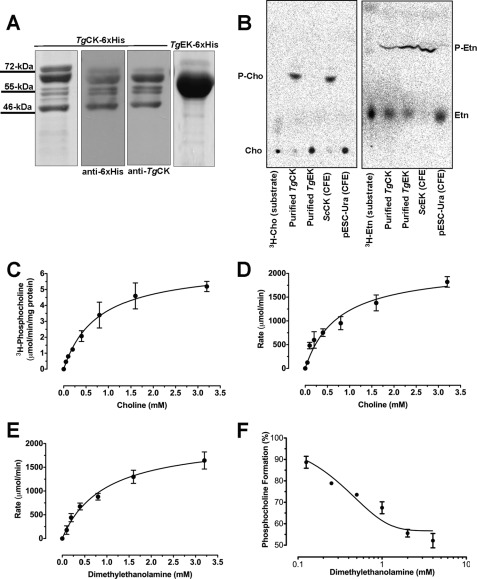

To classify these enzymes as choline and/or ethanolamine kinases according to their substrate specificity, we examined their activity. TgCK and TgEK with C-terminal His6 were purified from E. coli. Purified TgCK-His6 preparation contained two smaller bands (55 and 46 kDa) besides the expected kinase of 72 kDa, which were identified as shorter isoforms of TgCK-His6 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A; see below in Fig. 6). TgEK-His6 was purified to homogeneity as deduced by a 60-kDa band on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). The purified recombinant TgCK phosphorylated choline and ethanolamine as substrates (Fig. 1B). In contrast, TgEK showed an activity only for ethanolamine, revealing its substrate-specific nature.

FIGURE 1.

TgCK phosphorylates choline and ethanolamine and is inhibited by DME, whereas TgEK is specific to ethanolamine. A, the full-length ORFs of TgCK and TgEK were expressed with C-terminal His6 tag in the pET22b+ or pET28b+ vector, and purity was tested by Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE or anti-His6 (1:7000) or anti-TgCK (1:200) blot. B, thin layer chromatography of resolved catalytic products of choline and ethanolamine kinases. The products were identified by their co-migration with respective controls. Purified TgCK-His6 or TgEK-His6 was incubated with [3H]choline (Cho) or with [3H]ethanolamine (Etn) (37 °C, 4 min) prior to TLC analysis, and products were detected by phospho-imaging. Cell lysates from the S. cerevisiae KS106 (Δck/Δek) expressing ScCK1 or ScEK1 or harboring empty vector (pESC-Ura) served as positive or negative control. P-Cho, phospho-Cho; P-Etn, phospho-Etn; CFE, cell-free extract. C, Michaelis-Menten kinetics of TgCK-His6 by radioactive assay, determined by scintillation counting of phosphocholine from [3H]choline chloride (3.125 nCi/nmol, 0–3.2 mm, 4 min, 37 °C). D and E, Michaelis-Menten kinetics of TgCK-His6 with choline or DME was monitored by decrease in NADH absorbance (340 nm) in a pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase-coupled system. F, effect of DME (0–4 mm) on the formation of [3H]phosphocholine from choline (0.1 mm, 0.25 nCi/nmol) by purified TgCK-His6 was measured for 4 min at 37 °C. Values are means ± S.E. for three experiments.

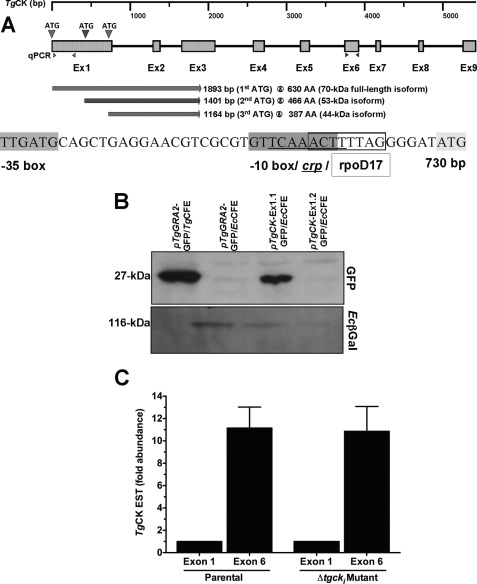

FIGURE 6.

Exon 1 of TgCK gene contains a cryptic promoter. A, schematic representation of the TgCK gene, exon structure, possible initiating codons in exon 1, and putative isoforms. The primer sets used to test the abundance of exon 1 and exon 6 are highlighted. The exon 1 sequence was analyzed by the BPROM algorithm for potential transcription start positions of bacterial genes regulated by σ70 (major E. coli promoter class). Linear discriminant function combines the characteristics describing functional motifs and oligonucleotide composition of these sites. BPROM has about 80% accuracy for recognition of E. coli promoters. B, immuno-blot of the cell-free extract (CFE) prepared from E. coli (Rosetta) and T. gondii tachyzoites using ant-GFP (1:10000) and anti-EcβGal (1:10000) antibodies. The TgCK-Ex1.1 consisted of a fragment until the third ATG (1–729 bp) and the TgCK-Ex1.2 ended with the second ATG (1–492 bp). Parasites expressing GFP (pTgGRA2-GFP/TgCFE) and bacteria harboring pTgGRA2-GFP plasmid (pTgGRA2-GFP/EcCFE) served as positive and negative controls, respectively. The E. coli β-galactosidase was included as a loading control. C, real-time PCR of exon 1 and exon 6 of TgCK transcript. The Δct was determined for expressed sequence tags in both parasite strains by normalizing with their respective TgElf1α transcript (housekeeping gene). The -fold change (i.e. ΔΔct) of exon 6 was calculated with respect to exon 1 for each strain. Values are means ± S.E. for three experiments.

TgCK Is Inhibited by a Choline Analog, DME

Our earlier work has shown that DME can block T. gondii growth by disrupting de novo PtdCho synthesis (7). Because TgCK is a probable enzymatic target of DME, we determined the biochemical features of TgCK using radioactive and photometric assays. The catalysis of [3H]choline by TgCK-His6 reached a plateau in response to substrate concentrations (Fig. 1C). The enzyme exhibited typical Michaelis-Menten kinetics with a Km value of 0.77 mm. Our assays of choline phosphorylation by photometry yielded a similar concentration kinetics and Km (0.74 mm) for TgCK (Fig. 1D). TgCK also recognized DME as its substrate exhibiting Michaelis-Menten kinetics with a Km of 0.94 mm, which is similar to its Km value for choline (Fig. 1E). In accord, DME inhibited phosphocholine formation by TgCK in radioactive assays exhibiting a Ki of 0.84 mm and IC50 of 0.95 mm (Fig. 1F); both values are similar to the Km for DME (0.94 mm). In further radioactive assays, we used 2 mm DME, which increased the Km of TgCK for choline by 3-fold without influencing the Vmax, signifying a competitive inhibition. The kinetics of DME metabolism by TgCK is consistent with the observed reduction of PtdCho synthesis in extracellular parasites and with the inhibition of parasite cultures by DME (IC50 ∼0.5 mm) (7).

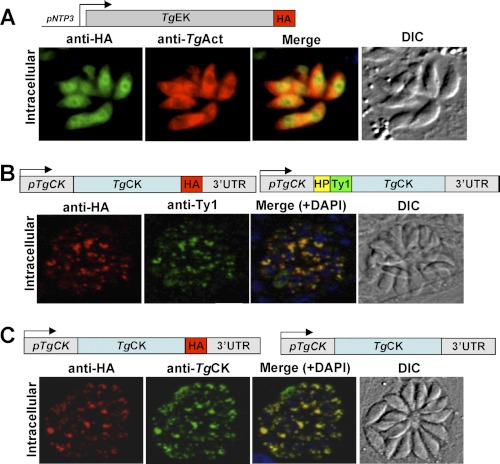

TgCK Displays Punctate Distribution, whereas TgEK Is Cytosolic

To determine the subcellular location of TgEK and TgCK, their C-terminal HA-tagged constructs (TgEK-HA, TgCK-HA) were generated for ectopic expression in T. gondii tachyzoites. As anticipated, TgEK-HA displayed a uniform cytosolic localization, which co-localized with a bona fide cytosolic marker protein, actin (TgActin) (Fig. 2A). Our attempts to detect and localize TgCK in stable transgenic parasites using a strong promoter pNTP3 were futile. Hence, we made a construct expressing TgCK-HA under the control of native regulatory elements for the protein localization. TgCK-HA displayed a punctate cytosolic signal in intracellular parasites (Fig. 2B), which did not localize with dense granule or cytosolic proteins such as TgGra1 and TgActin (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

TgEK is uniformly cytosolic, whereas TgCK displays punctate intracellular distribution. A, TgEK harboring a C-terminal HA tag (TgEK-HA) was expressed under the control of the pNTP3 promoter and co-localized with the parasite actin (TgAct). DIC, differential interference contrast. B, TgCK isoforms with a C-terminal HA tag (TgCK-HA) or a Ty1 epitope (TgCK-Ty1) following hydrophobic peptide (HP) were co-expressed under the control of the native regulatory elements. C, co-localization of TgCK was executed in hxgprt− parasites expressing TgCK-HA using anti-HA and mouse anti-TgCK serum.

The unexpected and unique cellular distribution and possible requirement of the N terminus for optimal targeting (see below) prompted us to localize TgCK tagged with a Ty1 epitope following its hydrophobic peptide. TgCK-Ty1 showed a similar dotted intracellular presence co-localizing with TgCK-HA (Fig. 2B). To further substantiate these findings, we generated mouse antisera against the purified enzyme, which identified a 70-kDa band corresponding to a full-length enzyme in the parasitized fibroblasts but none in uninfected cells (see Fig. 4E). Yet again, we observed a punctate cytosolic staining in wild-type intracellular parasites using anti-TgCK sera that remained unchanged in the axenic parasites (supplemental Fig. S4A). Consistently, immuno-staining of the transgenic parasites expressing TgCK-HA with anti-TgCK sera revealed a perfect co-localization (Fig. 2C), which was further corroborated in COS7 cells expressing V5-tagged TgCK (supplemental Fig. S4B). Briefly, we demonstrate that TgCK has a distinct punctate distribution and is stringently regulated, whereas TgEK is uniformly cytosolic.

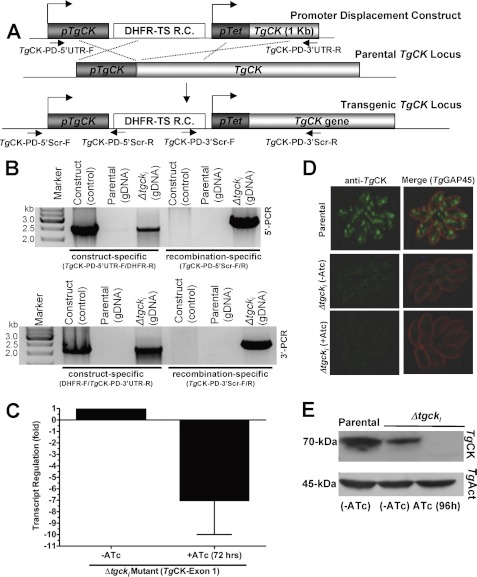

FIGURE 4.

Conditional mutagenesis of TgCK gene. A, scheme of the pTgCK promoter displacement by a tetracycline-regulatable pTetO7Sag4 promoter in the TaTi-Δku80 strain of T. gondii. The 2 kb of the promoter region and 1 kb following the initiating codon of TgCK were cloned into the pDT7S4 vector flanking the pTetO7Sag4 and DHFR-TS resistance cassette (R. C.). B, construct-specific PCR (TgCK-PD-5′-UTR-F/DHFR-R and DHFR-F/TgCK-PD-35′-UTR-R) confirmed expected bands in the plasmid and in the Δtgcki gDNA, but not in the parental strain. The recombination PCR using TgCK-PD-5′Scr-F/DHFR-R and DHFR-F/TgCK-PD-3′Scr-R primers, respectively, revealed 5′- and 3′-crossover in the Δtgcki mutant but none with control construct or parental gDNA. C, the qPCR of the TgCK transcript (exon 1) from the Δtgcki mutant prior to or following 72 h culture in anhydrotetracycline. Values are means ± S.E. for three experiments. D, TgCK expression under the control of the native (TaTi-Δku80 strain) or conditional (Δtgcki mutant) promoter. Intracellular tachyzoites were stained 29 days after infection with anti-TgGap45 (red, inner membrane complex marker) and anti-TgCK (green) antibodies. E, anti-TgCK (1:500) immuno-blot of the extract from the Δtgcki and TaTi-Δku80 strains. The TgActin (1:1000) served as a loading control.

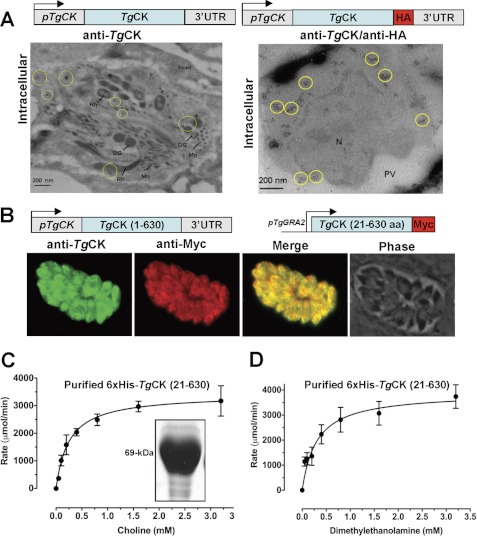

The N Terminus of TgCK Is Needed for Clustering but Not for Function

To identify the organelle underlying the atypical staining of TgCK, we performed immuno-gold electron microscopy. Notably, immuno-gold electron microscopy revealed the formation of enzyme clusters in the parasite cytosol, and no association with any organelle and/or membrane was detectable in the wild-type RH strain (Fig. 3A, left panel) as well as in the transgenic parasites expressing TgCK-HA (Fig. 3A, right panel). Both native and ectopic forms of choline kinase showed a perfect co-localization in the transgenic parasites. In further assays, we determined the role of the hydrophobic peptide in the formation of protein clusters. To this end, we first performed the N-terminal tagging of TgCK that rendered the enzyme undetectable and suggested that the N terminus is required for localization. Then, we transfected parasites with a Myc-tagged truncated TgCK (TgCKS-Myc) lacking the first 20 residues and localized the enzyme using the anti-Myc and anti-TgCK antibodies. TgCKS-Myc exhibited a more uniform presence in the parasite cytosol, suggesting that the N terminus of TgCK indeed contributes to its punctate distribution (Fig. 3B). In brief, these data suggest the hydrophobic peptide as a sequence supporting the enzyme clustering in the cytosol of T. gondii.

FIGURE 3.

The hydrophobic N-terminal peptide is required for clustering of TgCK but not for catalysis. A, immuno-gold electron microscopy of the wild-type (left) or of transgenic parasites expressing TgCK-HA (right) parasites using anti-TgCK and/or anti-HA antibodies. The transgenic parasite line was labeled with rat anti-HA and mouse anti-TgCK as primary antibodies and protein A/gold (anti-rat, 5 nm; anti-mouse, 10 nm)-conjugated secondary antibodies to co-localize the native and ectopic isoforms of TgCK. hcell, host cell; Mn, microneme; DG, dense granule; Rh, rhoptry; PV, parasitophorous vacuole; N, nucleus. B, TgCK lacking its N-terminal hydrophobic peptide and containing a Myc tag at the C terminus (TgCKs-Myc, red) was regulated by the pGRA2 and co-stained using anti-TgCK sera. C and D, a short TgCK lacking its hydrophobic peptide and containing an N-terminal tag (His6-TgCKS) was cloned in pET28b+, expressed in E. coli, and purified (67 kDa on SDS-PAGE). Michaelis-Menten kinetics of His6-TgCKS with choline (C) or DME (D) was monitored by decrease in NADH absorbance (340 nm) in a coupled-enzyme assay. Values are means ± S.E. for three experiments.

To test the significance of the hydrophobic peptide for protein activity, we expressed His6-TgCKS in E. coli and purified the enzyme to homogeneity (Fig. 3C, inset). Quite noticeably, when compared with full-length TgCK-His6 (Fig. 1, D and E), His6-TgCKS displayed ∼3-fold higher affinity for choline (Km = 0.26 mm, Fig. 3C) and DME (Km = 0.25 mm, Fig. 3D). The results show that the N-terminal is not needed for catalysis.

Choline Kinase Can Only Be Ablated by Conditional Mutagenesis

Our three attempts to directly delete the TgCK gene locus were futile, indicating an essential function of choline kinase, which prompted conditional ablation of the TgCK expression. To this end, our attempt for a two-step conditional mutagenesis was unsuccessful, probably due to stringent regulation of the enzyme. Therefore, we made an inducible mutant (Δtgcki) based on targeted displacement of the pTgCK promoter by the pTetO7Sag4 in the TaTi-Δku80 strain, allowing an efficient crossover and tetracycline-regulated expression (20). The promoter-displacement (PD) construct harbored the 5′-UTR preceding the start codon and a partial TgCK gene fragment, both inserts flanking the DHFR-TS and the pTetO7Sag4 promoter (Fig. 4A). Pyrimethamine-resistant parasites were selected and PCR-analyzed, confirming the displacement of the pTgCK (Fig. 4B). The construct-specific PCR identified the DHFR-TS resistance cassette adjacent to the 5′- and 3′-inserts in the genome of the promoter-displaced mutant (Δtgcki) and in control construct but not in the parental gDNA. Moreover, PCRs for the 5′- and 3′-crossovers amplified the expected bands in Δtgcki gDNA but not in the parental or control construct. Sequencing of the 5′- and 3′-fragments confirmed the events of homologous crossover at the TgCK locus.

The qPCR using the total RNA isolated from the mutant showed 7× repression of the TgCK mRNA (exon 1) after 72 h of culture in anhydrotetracycline (ATc; Fig. 4C). A similar reduction was also observed following drug treatment when primers were chosen in downstream sequences such as in the second half of exon 1 or exon 6 (data not shown). Immuno-fluorescence of the Δtgcki mutant showed a reduced level of choline kinase (∼70-kDa) when compared with the parental strain (Fig. 4D) when images were taken at identical intensity. Consistently, densitometric quantifications of three independent immuno-blots yielded about 60% diminution in the protein level in the mutant (Fig. 4E). As expected, enzyme was not detectable after 96 h of culture in ATc (Fig. 4, D and E). Together, these results show that choline kinase activity can only be ablated by conditional mutagenesis.

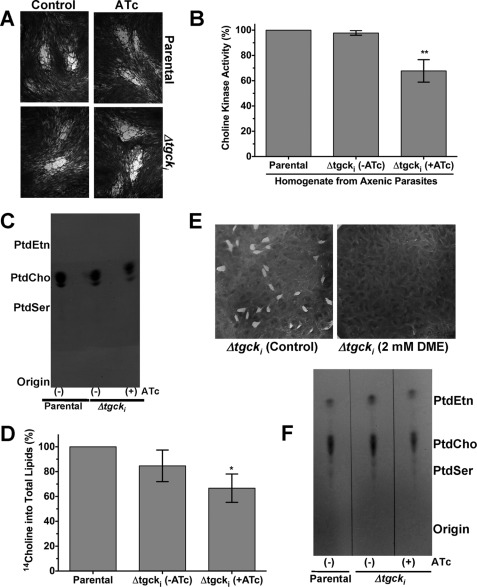

The CDP-Choline Pathway Cannot Be Abrogated in Δtgcki Mutant

Next, we focused on characterizing the Δtgcki mutant for its in vitro growth and phospholipid synthesis. Surprisingly, the mutant survived continued passages in cultures irrespective of the ATc in plaque assays (Fig. 5A, supplemental Fig. S5A). No discernable growth defect despite a complete protein loss in the mutant motivated us to elucidate the mechanism underlying its survival and membrane biogenesis. To this end, we examined the Δtgcki mutant for choline kinase activity and incorporation of precursor into PtdCho during parasite replication. The enzyme activity in the mutant extract was similar to the parental strain and decreased by about 35% following its culture in ATc (Fig. 5B). Similarly, choline labeling of PtdCho in the untreated mutant was comparable with the parental strain and reduced to ∼65% in ATc-treated cultures (Fig. 5, C and D). Consistently, the Δtgcki strain displayed susceptibility to inhibition of choline kinase activity by DME, which abrogated its plaque formation (Fig. 5E). The control cultures displayed 4–8 tachyzoites in ∼80% of vacuoles, and 15–20% of them harbored two parasites. A prominent decrease in the parasites per vacuole was observed in DME-treated cultures, where 80–100% vacuoles showed only 2–4 tachyzoites (supplemental Fig. S5B). The results confirm that the plaque inhibition is due to an impaired replication of tachyzoites, which apparently do not obtain adequate PtdCho from the host cell. The persistence of kinase activity and labeling of parasite PtdCho, irrespective of the drug exposure, confirms the presence of a functional CDP-choline pathway in the Δtgcki strain.

FIGURE 5.

The parasite growth and CDP-choline pathway are not impaired despite a major knockdown of TgCK in Δtgcki mutant. A, plaques formed by the Δtgcki and parental strain with or without ATc. Confluent HFF monolayers were infected with 200 parasites and stained with crystal violet after 7 days of infection. B, choline kinase activity was measured in the protein extract using [14C]choline (0.1 μCi, 10 μm, 30 min, 37 °C). Statistical significance (**, p < 0.0031) was estimated by one-way analysis of variance group t test. C and D, choline labeling of the parasite phospholipids. The parasitized (multiplicity of infection = 3) monolayers of human foreskin fibroblasts were cultured for 40 h in medium containing [14C]choline (0.1 μCi/ml). Parasites were washed with PBS, and lipids were extracted. [14C]Choline labeling into phospholipids was visualized by x-ray exposure of the TLC plate for 48 h (C) or quantified by scintillation counting (D). Statistical significance (*, p < 0.014) was estimated by one-way analysis of variance group t test. Values are means ± S.E. for three experiments. E, inhibition of the Δtgcki mutant by DME. Confluent HFF monolayers infected with the mutant parasites (200 tachyzoites) were cultured for 7 days, with or without DME, and stained with crystal violet. F, iodine-stained TLC-resolved phospholipids from the Δtgcki and parental strains. Lipids were extracted from an equal number of parasites (108), separated by TLC, and then visualized by iodine vapors in a closed glass tank. The ATc (0.5 μm) treatment was performed for 2–3 passages in culture prior to setting up the pertinent assays.

The Off-state Δtgcki Mutant Can Tolerate Substantial Reduction of PtdCho

We compared the major phospholipid profiles of the mutant with the parental strains. No change in iodine staining of PtdCho and other major phospholipids (PtdEtn and PtdSer) of the Δtgcki strain was noticeable in untreated cultures, and a reduction of 35% in PtdCho content was observed after ATc treatment (Fig. 5F). The chemical quantification of total lipid phosphorous by an established method (21) revealed 0.54 nmol of PtdCho/106 parasites of the parental strain and 0.50 and 0.32 nmol in the on and off states of the mutant, respectively. The aforesaid decrease in enzyme activity and reduction in PtdCho synthesis is equivalent to the 36% decline in the amount of PtdCho. It appears that the parasite can ensure its survival and produce sufficient amount of PtdCho for membrane biogenesis despite a major knockdown of full-length choline kinase. Importantly, a normal growth despite a substantial reduction in PtdCho indicates a compositional plasticity of T. gondii membranes and inability to salvage host-derived PtdCho in sufficient amount to trade off the reduced protein and phospholipid levels.

Exon 1 of TgCK Contains a Prokaryotic-type Promoter

Next, we investigated the mechanism underlying the persistent presence of choline kinase activity in the mutant in the off state. The expression of small His-tagged variants, namely 55- and 46-kDa isoforms, in E. coli when using the cDNA of choline kinase (Fig. 1A) indicated the presence of a prokaryotic-type promoter and/or of alternative start codons in ORF. We screened the first exon of choline kinase, which indeed identified two additional ATG codons located in-frame with the downstream exons (Fig. 6A). The protein synthesis commencing at the second and third start codons can encode 53- and 44-kDa enzymes, respectively, both of which contain a complete choline kinase domain as well as correspond to the observed His-tagged protein species in E. coli. Based on this notion, we expressed GFP under the control of the two varying exon 1 sequences in E. coli Rosetta strain. The pTgCK-Ex1.1 consisted of a fragment until the third ATG (1–729 bp), and the pTgCK-Ex1.2 ended with the second ATG (1–492 bp). We also included pertinent negative (GFP driven by pTgGRA2 in E. coli) and positive (parasites expressing GFP under the control of the pTgGRA2) controls for anti-GFP immuno-blot analysis (Fig. 6B). Indeed, the pTgCK-Ex1.1 was sufficient in driving the expression of GFP in E. coli as judged by a 27-kDa band similar to the positive control (pTgCK-Ex1.1-GFP/EcCFE and pTgGRA2-GFP/TgCFE in Fig. 6B). In contrast, no GFP expression was detected by pTgGRA2-GFP (negative control) or pTgCK-Ex1.2-GFP (1–492 bp) construct.

Further analysis of exon 1 by the BPROM program predicted a prokaryotic-type promoter at position 726 (linear discriminant function: 3.28) harboring a −10 box at position 711 bp (GTTCAAACT), −35 box at 686 bp (TTGATG), and binding for two transcription factors crp (TCAAACTT at position 713 bp) and rpoD17 (ACTTTTAG at position 717 bp) (Fig. 6A). To investigate whether exon 1 can indeed function as a promoter in T. gondii, leading to shorter transcripts with higher abundance, we quantified two different expressed sequence tags derived from separate exons of the TgCK gene in parental and mutant strains. The first primer pair anneals in exon 1, and the second set binds in exon 6 (Fig. 6A). In line with the observations from the bacterial expression, we quantified a 10-fold higher amount of exon 6 when compared with exon 1 in both strains (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results show that TgCK-Exon1 is capable of functioning as a promoter in bacteria, which has potential to express shorter transcripts with a higher abundance in T. gondii.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate an exceptional metabolic plasticity in T. gondii that allows the parasite to offset the stress imposed upon its membrane biogenesis. The first interesting and unexpected finding implies that the parasite harbors multiple isoforms of choline kinase encoded by a single gene with two promoters. Secondly, T. gondii displays a compositional flexibility of the parasite membranes that helps in sustaining a normative growth despite about 35% decline in PtdCho content. Finally, unlike P. falciparum (22) and its mammalian host (8), Toxoplasma lacks the enzyme activity (7) or the gene annotation for a functional serine decarboxylase and phosphoethanolamine or PtdEtn methyltransferase to make PtdCho from serine and/or ethanolamine (supplemental Fig. S1). Conversely, choline kinase can phosphorylate ethanolamine, and thus, has potential to counteract the loss of ethanolamine kinase and to sustain de novo synthesis of PtdEtn in T. gondii. The parasite also harbors a PtdSer decarboxylase route to produce PtdEtn from PtdSer (supplemental Fig. S1). The parasite resilience to a perturbation of choline kinase, compositional flexibility of its membranes, and likely redundant routes of PtdEtn synthesis can confer an adjustable membrane biogenesis to T. gondii in dissimilar nutrient environments or host cells. The observed metabolic plasticity might allow T. gondii to fine-tune membrane biogenesis according to the intracellular niche and contribute to its evolution as a promiscuous pathogen.

As an intracellular parasite replicating in the nutrient-rich host cell, T. gondii has potential access to host-derived phospholipids and their intermediates to satisfy membrane biogenesis. The parasite recruits host endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in proximity to the parasite vacuole (23), and these organelles, harboring PtdCho and PtdEtn synthesis in host cells (8), may donate these lipids to T. gondii. The recruitment of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by T. gondii can supply cholesterol to the parasite (24), and being rich in PtdCho (25), the host derived LDL offers a second route to obtain this lipid. The analog-inhibition assays and a reduced PtdCho content of the conditional mutant, however, advocate against the salvage of host PtdCho in sufficient amounts to bypass the CDP-choline pathway in T. gondii. In agreement, our results on transport of 12-(N-methyl-N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl))-conjugated lipid analogs do not show any significant import of PtdCho by free tachyzoites.3 Our results reveal a quantitative concordance between the enzyme activity and PtdCho synthesis, implying a likely dependence of the parasite on the de novo CDP-choline route to realize its membrane biogenesis. Besides, the results indicate that the previous (7) and hereby-reported antiparasitic effect of DME is likely not caused by decline in PtdCho. Instead, it might be a consequence of accrued PtdDME that is not methylated to PtdCho due to lack of a functional PtdEtn methyltransferase in T. gondii.

Conditional mutagenesis of the choline kinase promoter identified yet another protein activity in T. gondii tachyzoite that was refractory to regulation. Although not precluded, persistent enzyme activity is likely not encoded by a different gene because we did not detect expression of an unrelated choline kinase in T. gondii. Ectopic expression of an active protein from the promoter displacement construct is also unlikely because the 3′-crossover fragment (the first exon) would encode, if any, a truncated protein of 258 amino acids (27 kDa) lacking a catalytic domain. Being under a conditional promoter, it must be regulatable (no activity in the off state), which is not the case. Further, no band corresponding to a 27-kDa product was detectable by anti-TgCK immuno-blot (not shown). Our work suggests a functional promoter within the first exon of choline kinase that can direct expression through two start codons at position 730 and 493 bp located in-frame with downstream exons. The use of these codons can yield 53- and 44-kDa isoforms, each containing a kinase domain and catalytic motifs. In accord, we occasionally detected the two variants of similar sizes by anti-TgCK blot (supplemental Fig. S5C). Our attempts to express the isoforms in E. coli have been futile, yielding inclusions and inactive protein. The unequivocal identification, characterization, and regulation of the variants, therefore, require further research.

The expression of GFP under the control of exon 1 and of shorter protein isoforms shows that exon 1 is also functional as a promoter in E. coli. These findings resonate with a previous study showing the presence of a promoter in the first exon of the SPG4 gene, which can govern the synthesis of a short spastin isoform (26). The exon 1 promoter is likely active in T. gondii, as shown by higher abundance of exon 6. Our futile attempts to express GFP under the sole control of the pTgCK-Ex1 entail that a cis-acting element may be necessary for function of this cryptic promoter in the parasite. Further research is required to examine the functional relevance of TgCK-Ex1 in T. gondii.

Quite notably, the Km of full-length choline kinase encoded by TgCK (0.77 mm) for choline is manyfold higher than parasite (PfCK, 0.14 mm (27); TbCK, 0.032 mm (28)) and nonparasite (HsCKα1, 0.2 mm (29); ScCK 0.27 mm (30)) peers. In addition, TgCK protein harbors a hydrophobic sequence at the N terminus that is nonessential for catalysis but appears to be required for its clustering in the cytosol. The deletion of the N-terminal peptide presumably changes the conformation of TgCK and increases the protein affinity by 3-fold (0.26 mm), which is in range of other choline kinases. Hence, it is plausible that shorter isoforms have a similarly higher affinity for choline and allow the parasite to sustain a low choline milieu or the absence of full-length isoform. It is known that the three isoforms of the mouse enzyme can exist as hetero-/homo-oligomers, which are suggested to regulate the catalysis (31). The significance of choline kinase isoforms and of whether the enzyme clusters are catalytically more efficient in T. gondii requires further studies. Irrespective of the mechanism, disruption of PtdCho synthesis by pharmacological inhibition of CDP-choline route remains an effective strategy to arrest the membrane biogenesis and growth of T. gondii.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Grit Meusel and Maria Hellmund (Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany) for assistance and Thomas Günther-Pomorski (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) for the initial contribution to this work. We thank Scott Landfear (Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR) for a critical review of manuscript.

This work was supported by German Research Foundation Grants GRK1121 (to N. G. and A. H.) and SFB618 (to N. G. and R. L.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S5.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) ACL12052 and ADY76966

V. Sampels, A. Hartmann, I. Dietrich, I. Coppens, L. Sheiner, B. Striepen, A. Herrmann, R. Lucius, and N. Gupta, unpublished results.

- PtdCho

- phosphatidylcholine

- PtdEtn

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PtdSer

- phosphatidylserine

- ATc

- anhydrotetracycline

- CK

- choline kinase

- EK

- ethanolamine kinase

- DHFR-TS

- dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase

- DME

- N,N-dimethylethanolamine

- HFF

- human foreskin fibroblast

- HXGPRT

- hypoxanthine xanthine guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase

- PD

- promoter-displacement

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- gDNA

- genomic DNA

- Ec

- E. coli

- Hs

- H. sapiens

- Pf

- P. falciparum

- Sc

- S. cerevisiae

- Tb

- Trypanosoma brucei

- Tg

- T. gondii.

REFERENCES

- 1. Black M. W., Boothroyd J. C. (2000) Lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 607–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fox B. A., Bzik D. J. (2002) De novo pyrimidine biosynthesis is required for virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 415, 926–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chaudhary K., Darling J. A., Fohl L. M., Sullivan W. J., Jr., Donald R. G., Pfefferkorn E. R., Ullman B., Roos D. S. (2004) Purine salvage pathways in the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31221–31227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blume M., Rodriguez-Contreras D., Landfear S., Fleige T., Soldati-Favre D., Lucius R., Gupta N. (2009) Host-derived glucose and its transporter in the obligate intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii are dispensable by glutaminolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12998–13003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Welti R., Mui E., Sparks A., Wernimont S., Isaac G., Kirisits M., Roth M., Roberts C. W., Botté C., Maréchal E., McLeod R. (2007) Lipidomic analysis of Toxoplasma gondii reveals unusual polar lipids. Biochemistry 46, 13882–13890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maréchal E., Azzouz N., de Macedo C. S., Block M. A., Feagin J. E., Schwarz R. T., Joyard J. (2002) Synthesis of chloroplast galactolipids in apicomplexan parasites. Eukaryot. Cell 1, 653–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta N., Zahn M. M., Coppens I., Joiner K. A., Voelker D. R. (2005) Selective disruption of phosphatidylcholine metabolism of the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii arrests its growth. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16345–16353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vance J. E., Vance D. E. (2004) Phospholipid biosynthesis in mammalian cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 82, 113–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li Z., Vance D. E. (2008) Phosphatidylcholine and choline homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1187–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charron A. J., Sibley L. D. (2002) Host cells: mobilizable lipid resources for the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3049–3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim K., Kim K. H., Storey M. K., Voelker D. R., Carman G. (1999) Isolation and characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae EKI1 gene encoding ethanolamine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14857–14866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Porter T. J., Kent C. (1992) Choline/ethanolamine kinase from rat liver. Methods Enzymol. 209, 134–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uchida T., Yamashita S. (1992) Choline/ethanolamine kinase from rat brain. Methods Enzymol. 209, 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Donald R. G., Carter D., Ullman B., Roos D. S. (1996) Insertional tagging, cloning, and expression of the Toxoplasma gondii hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase gene: use as a selectable marker for stable transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14010–14019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donald R. G., Roos D. S. (1993) Stable molecular transformation of Toxoplasma gondii: a selectable dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase marker based on drug resistance mutations in malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11703–11707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fölsch H., Pypaert M., Schu P., Mellman I. (2001) Distribution and function of AP-1 clathrin adaptor complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 595–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meissner M., Brecht S., Bujard H., Soldati D. (2001) Modulation of myosin A expression by a newly established tetracycline repressor-based inducible system in Toxoplasma gondii. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, E115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Dooren G. G., Tomova C., Agrawal S., Humbel B. M., Striepen B. (2008) Toxoplasma gondii Tic20 is essential for apicoplast protein import. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13574–13579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sheiner L., Demerly J. L., Poulsen N., Beatty W. L., Lucas O., Behnke M. S., White M. W., Striepen B. (2011) A systematic screen to discover and analyze apicoplast proteins identifies a conserved and essential protein import factor. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rouser G., Siakotos A. N., Fleischer S. (1966) Quantitative analysis of phospholipids by thin layer chromatography and phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids 1, 85–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Witola W. H., El Bissati K., Pessi G., Xie C., Roepe P. D., Mamoun C. B. (2008) Disruption of the Plasmodium falciparum PfPMT gene results in a complete loss of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis via the serine-decarboxylase-phosphoethanolamine-methyltransferase pathway and severe growth and survival defects. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27636–27643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinai A. P., Webster P., Joiner K. A. (1997) Association of host cell endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria with the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole membrane: a high affinity interaction. J. Cell Sci. 110, 2117–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coppens I., Sinai A. P., Joiner K. A. (2000) Toxoplasma gondii exploits host low-density lipoprotein receptor-mediated endocytosis for cholesterol acquisition. J. Cell Biol. 149, 167–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (1977) The low-density lipoprotein pathway and its relation to atherosclerosis. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 46, 897–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mancuso G., Rugarli E. I. (2008) A cryptic promoter in the first exon of the SPG4 gene directs the synthesis of the 60-kDa spastin isoform. BMC Biol. 6, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alberge B., Gannoun-Zaki L., Bascunana C., Tran van Ba C., Vial H., Cerdan R. (2010) Comparison of the cellular and biochemical properties of Plasmodium falciparum choline and ethanolamine kinases. Biochem. J. 425, 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gibellini F., Hunter W. N., Smith T. K. (2008) Biochemical characterization of the initial steps of the Kennedy pathway in Trypanosoma brucei: the ethanolamine and choline kinases. Biochem. J. 415, 135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallego-Ortega D., Ramirez de Molina A., Ramos M. A., Valdes-Mora F., Barderas M. G., Sarmentero-Estrada J., Lacal J. C. (2009) Differential role of human choline kinase α and β enzymes in lipid metabolism: implications in cancer onset and treatment. PLoS One 4, e7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim K. H., Voelker D. R., Flocco M. T., Carman G. M. (1998) Expression, purification, and characterization of choline kinase, product of the CKI gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6844–6852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aoyama C., Ohtani A., Ishidate K. (2002) Expression and characterization of the active molecular forms of choline/ethanolamine kinase-α and -β in mouse tissues, including carbon tetrachloride-induced liver. Biochem. J. 363, 777–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.