Background: Chronic treatment with a μ-receptor antagonist increases the δ ability of the agonist to promote natural killer cell functions in alcohol- and non-alcohol-treated animals.

Results: Opiate receptor antagonist reduces the receptor heterodimerization but increases ligand sensitivity.

Conclusion: Receptor dimerization controls feedback interaction between μ-and δ-opiate receptors.

Significance: Studying opiate receptor feedback interaction will promote better opiate-based therapy for immune diseases.

Keywords: Alcohol, Breast Cancer, Cellular Immune Response, Opiate Opioid, Receptor Desensitization, Receptor Regulation

Abstract

In the natural killer (NK) cells, δ-opiate receptor (DOR) and μ-opioid receptor (MOR) interact in a feedback manner to regulate cytolytic function with an unknown mechanism. Using RNK16 cells, a rat NK cell line, we show that MOR and DOR monomer and dimer proteins existed in these cells and that chronic treatment with a receptor antagonist reduced protein levels of the targeted receptor but increased levels of opposing receptor monomer and homodimer. The opposing receptor-enhancing effects of MOR and DOR antagonists were abolished following receptor gene knockdown by siRNA. Ethanol treatment increased MOR and DOR heterodimers while it decreased the cellular levels of MOR and DOR monomers and homodimers. The opioid receptor homodimerization was associated with an increased receptor binding, and heterodimerization was associated with a decreased receptor binding and the production of cytotoxic factors. Similarly, in vivo, opioid receptor dimerization, ligand binding of receptors, and cell function in immune cells were promoted by chronic treatment with an opiate antagonist but suppressed by chronic ethanol feeding. Additionally, a combined treatment of an MOR antagonist and a DOR agonist was able to reverse the immune suppressive effect of ethanol and reduce the growth and progression of mammary tumors in rats. These data identify a role of receptor dimerization in the mechanism of DOR and MOR feedback interaction in NK cells, and they further elucidate the potential for the use of a combined opioid antagonist and agonist therapy for the treatment of immune incompetence and cancer and alcohol-related diseases.

Introduction

Endogenous opioid peptides, such as enkephalins and endorphins, which control the functions of the neuroendocrine system, enhance immune function and prevent cancer growth by stimulating NK2 cell cytolytic activity. These opioid peptides regulate NK cell functions by acting directly on the spleen and by altering the neuroendocrine-immune system function (1–3). These opioid peptides are also involved in controlling ethanol-modulating effects on innate immune function (4–6). In the central nervous system, β-endorphin and enkephalins are known to bind to classical DOR and MOR (7). Opioid receptors have been shown to be present in splenic cells (8), including NK cells (9). Acute treatments of opioid receptor agonists have been shown to stimulate NK cell cytolytic activity, and an opioid receptor antagonist blocks β-endorphin-stimulated NK cell function in the spleen (3). Chronic alcohol intake also has been shown to reduce the cytolytic function of NK cells in the spleen (3). Ethanol action on NK cells is partly mediated by its suppression of the production of endogenous opioid peptides and their receptors (10–13). Previously, we showed that chronic treatment with naltrexone increases the NK cell cytolytic activity of splenocytes of control and ethanol-fed rats (9). We also showed that treatment with naltrexone or with a MOR-specific antagonist d-Phe-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Arg-Thr-penicillamine-Thr-NH2 decreased MOR-ligand binding but increased DOR-ligand binding, whereas treatment with the DOR-specific antagonist naltrindole increased MOR-ligand binding but decreased DOR-ligand binding in the splenocytes (9). These data suggest that there may exist a negative feedback interaction between MOR and DOR in the spleen regulating NK cell function. The molecular basis for the opioid receptors feedback interaction was not determined.

Opioid receptors are members of the large superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (14). Like many G protein-coupled receptors, DOR and MOR receptors are constitutively active, producing spontaneous regulation of G protein and effectors in the absence of agonists (15, 16). A large body of evidence for the existence of G protein-coupled receptors as dimer and monomer has been accumulated in recent years. G protein-coupled receptor dimerization has been demonstrated to be a physiological process that modifies receptor pharmacology and regulates function (17). In the opioid receptor family, DOR has been shown to interact with both MOR and κ-opioid receptors to form heterodimers (17, 18). Studies of MOR-DOR dimerization identified that heterodimerization of these receptors reduces affinities for highly selective MOR or DOR ligands (17). Because DOR and MOR are present in splenocytes (19), it is possible that DOR and MOR dimers also exist in NK cells. Hence, we test the hypothesis, using both in vitro and in vivo model systems, that DOR and MOR antagonize each other's ligand binding ability and function on NK cells by increasing the physical association between them to form heterodimers. Furthermore, we test whether an opioid antagonist reduces protein levels of the targeted receptor and thereby increases levels of opposing receptor monomer and homodimer and their ligand binding ability and functions. Additionally, we test whether ethanol increases opioid receptor heterodimerization to suppress functions in NK cells. Because NK cells participate in cell-mediated immune response to tumor cells, we also determined the effectiveness of the combination treatment of opioid agonists and antagonists in prevention of NMU-induced mammary tumor growth.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Alcohol Feeding with or without Opioid Agonist and/or Antagonist Treatments in Animals

Male Fischer-344 rats, 150–175 g body weight, were maintained in a controlled environment, given free choice of water, and fed a liquid diet containing alcohol (8.7% v/v) or pair-fed an isocaloric liquid diet (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ). The ethanol treatment regimen used has been shown to maintain blood alcohol levels within the range of 115–123 mg/dl between days 10 and 30 (20). We used pair-fed rats as our control rats to calorie-match the alcohol-fed group. Furthermore, we have previously shown that pair-fed animals and ad lib-fed rodent chow animals had similar NK cell cytolytic activity, proliferative action to mitogens, and cytokine production (3, 4). After 2 weeks of adjustment to the diet, each animal was s.c. implanted with either a naltrexone or a naltrexone-placebo pellet (100 mg/pellet, 60-day release; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). These animals were given daily intraperitoneal injections of saline or a δ-opioid receptor agonist [d-Pen2,p-chloro-Phe4,d-Pen5]enkephalin (DPDPE; Sigma) using 100 μg/kg everyday for a period of 3 weeks. Spleen tissues of these animals were used for preparation of splenocytes as described previously (3).

Treatment with or without an Opioid Antagonist and/or an Agonist in Carcinogen-treated Animals

The physiological effects of a combined treatment of opioid antagonist and agonist were studied in vivo by determining their effects on the levels of the cytotoxic factors of NK cells in the spleen as well as the ability to inhibit NMU-induced mammary tumor growth of these opiodergic agents. In this study, 50-day-old virgin female Fischer rats were injected with a dose of NMU (50 mg/kg body weight). Nine weeks after NMU injection, animals were implanted with naltrexone pellets (100 mg, 60 days release) or placebo pellets under the skin. Seven days after naltrexone pellet implantation, DPDPE (100 μg/kg body weight) was injected daily i.p. until animals were sacrificed at 16 weeks. Animals were palpated every week to check for tumor growth. Tumor length and width were measured with a calibrator. At the end of this treatment, animals were sacrificed; tumors were collected, and slices of tumors were put in formalin and processed for histology staining. Animal surgery and care were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and complied with National Institutes of Health policy.

Opioid Agonist and Antagonist Treatments in RNK16 Cells

For in vitro experiments, we used RNK16 cells, a Fisher 344 rat-derived rat natural killer cell line. These cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 50 μm β-mercaptoethanol. During experimentation, 1 × 106 cells/well were plated in a 12-well plate for 24 h. Cells were starved with serum-free media for 1 h and then treated with naltrexone (10 ng/ml) or naltrindole (50 μm). These treatments were repeated at 24-h intervals for a period of 72 h. Cultures were additionally treated with [d-Ala2,N-MePhe4,Gly-ol]enkephalin (DAMGO; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, 50 μm) or DPDPE (10 nm) or vehicle treatments for 24 h prior to the termination of the experiment.

Knockdown of DOR and MOR Genes by siRNA in RNK16 Cells

DOR and MOR genes were knocked down from RNK16 cells using Rn_Oprd1_1 HP siRNA or Rn_Oprm1_2 HP siRNA (both from Qiagen). Immediately before transfection, 37.5 ng of siRNA was complexed with 3 μl of HiPerfect reagent (Qiagen) by incubating for 10 min at room temperature in 100 μl of culture medium without serum. This complex was added dropwise to 1.5 × 106 cells in each well of a 24-well plate. Antagonist was added and incubated at 37 °C, 7.5% CO2 for 72 h. This is followed by DOR or MOR agonist, DOR or MOR antagonist, or vehicle treatments for 24 h.

Opioid Agonists and Antagonists Treatments with or without Ethanol in RNK16 Cells

RNK16 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 50 μm β-mercaptoethanol. During experimentation, 1 × 106 cells/well were plated in 12-well plate for 24 h. Cells were starved with serum-free media for 1 h before adding ethanol (50 mm) with or without naltrexone (10 ng/ml) or naltrindole (50 μm). These treatments were repeated at 24-h intervals for a period of 72 h. These cultures were additionally treated with DAMGO (50 μm) or DPDPE (10 nm) or vehicle treatments for 24 h prior to the termination of the experiment.

Opioid Receptor Binding Assays

Spleens of experimental animals were dissociated, and erythrocytes were removed by a 5-s hypotonic shock with sterile distilled water, and splenocytes were isolated and incubated at a concentration of 1–4 × 106/well with various concentrations of [3H]naltrindole or [3H]DAMGO (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in 96-well plates for 4.5 h at room temperature in Ca2+- and Mg2+-deficient Hanks' balanced salt solution. Unlabeled naltrindole (50 μm; Sigma) and DAMGO (50 μm; Sigma) were used to assess nonspecific binding. Incubation was terminated by harvesting cell contents to Whatman glass-fiber filters, which were then air-dried and counted in a β-counter. For in vitro studies, we used the rat-derived NK cell line RNK16 cells (1–4 × 106). Naltrexone (10 ng/ml, Sigma) and DPDPE (10 nm) were used as MOR antagonist and DOR agonist, respectively, for in vitro studies.

Immunoprecipitation of Spleen and RNK16 Lysates by DOR or MOR Antibodies

Spleen and RNK16 lysates were immunoprecipitated by anti-MOR or DOR antibodies (rabbit polyclonal, R&D Antibodies, Las Vegas, NV). 10 μg of either antibody was coupled to protein A/G resin and then cross-linked with disuccinimidyl suberate using cross-link immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce) to eliminate the co-elution of antibody with antigen during the elution step. The lysate (500 μg) was then immunoprecipitated with antibody cross-linked resin. Antigen (DOR or MOR) was eluted by elution buffer and subsequently used for SDS-PAGE. This antigen was free from any antibody contamination.

Detection of DOR and MOR Protein Levels by Western Blot

After immunoprecipitation and subsequent elution, DOR or MOR were detected by 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, followed by probing with anti-DOR or anti-MOR antibodies (1:1000; rabbit polyclonal, Millipore). Receptor bands were identified by clean blot immunoprecipitation detection reagent (HRP, Pierce) followed by chemiluminescent detection.

Detection of Cytotoxic Factors by Western Blot

For protein analysis, 2 × 106 RNK16 cells or splenocytes were subjected to standard SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes following standard procedures. Protein blots were probed with Granzyme-B mAb, Perforin polyclonal Ab, and IFN-γ polyclonal antibody (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA; 1:1000), and actin mAb (Oncogene, San Diego) to normalize values. After chemiluminescence detection (ECL plus, Amersham Biosciences), densitometric analyses were performed using Scion Image software.

Immunohistochemistry

Cell cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then in 70% ethanol for an additional 30 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies used were polyclonal primary rabbit antibody for MOR (1:500; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and monoclonal antibody for DOR (1:500; Chemicon, Anytown, MA). The secondary antibody used to react with mouse primary antibodies was Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (4 mg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and the secondary antibody used to react with rabbit primary antibody was Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (4 mg/ml; Molecular Probes). Fluorescence images were captured with a Cool SNAP-pro CCD camera coupled to a Nikon-TE 2000 inverted microscope. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

Statistical Analysis

The data shown in the figures and text are mean ± S.E. values. Data comparisons between two groups were made using t tests. Comparisons among multiple groups were made using one-way analysis of variance and Student-Newman-Keuls test as a post hoc test. Differences in average tumor incidence, tumor number, and tumor volume were assessed using two-way analysis of variance with a Bonferroni post-test at the level of α = 0.05. To evaluate tumor type, a χ2 test was performed. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Interaction between DOR and MOR in Regulation of Ligand Binding in NK Cells

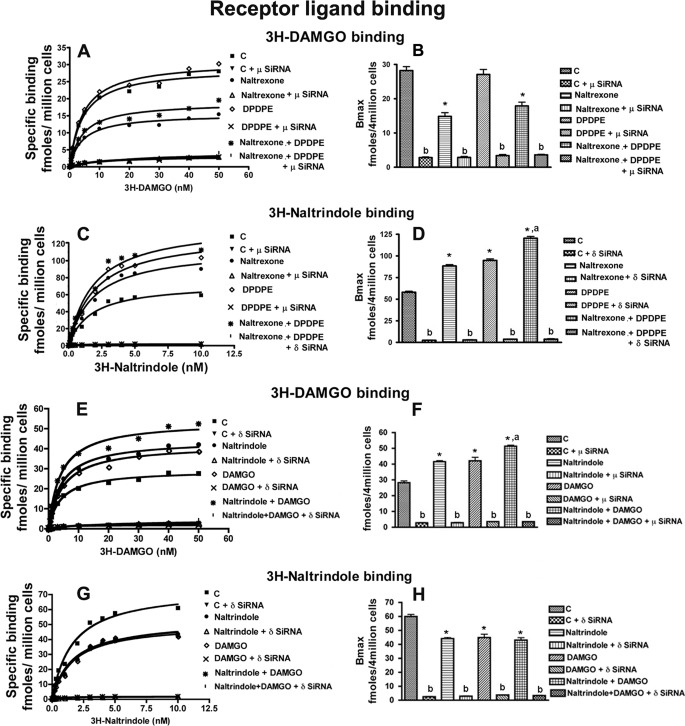

We tested the possibility that there may exist an intrinsic inhibitory feedback interaction between the constitutively active DOR and MOR in NK cells. To test this, in vitro studies were conducted in which the effects of MOR and DOR antagonists and agonists on the binding of a DOR- or MOR-specific ligand were determined in RNK16 cells. Chronic treatment with a MOR antagonist naltrexone (9) significantly decreased MOR ligand ([3H]DAMGO) binding (Fig. 1, A and B, and supplemental Fig. 1, A and B) but increased DOR ligand ([3H]naltrindole) binding (Fig. 1, C and D, and supplemental Fig. 1, C and D) in RNK16 cells. However, acute treatment for 24 h with MOR agonist DAMGO increased MOR but not DOR binding (Fig. 1, E–H; we tested opiate agonist effect acutely because chronic treatment is known to suppress the receptor binding with ligand, see Ref. 19). DAMGO treatment suppressed the ability of naltrexone to reduce MOR binding (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B) but did not affect naltrexone-altered DOR binding (supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). DOR agonist DPDPE alone did not change the MOR binding but increased DOR binding (Fig. 1, A–D, and supplemental Fig. 1, A–D). This DOR agonist was not able to promote the inhibitory effect of naltrexone on MOR but significantly increased naltrexone stimulatory effect on DOR binding (Fig. 1, A–D). Similarly, chronic treatment with the DOR antagonist naltrindole significantly decreased its targeted δ-receptor binding but increased its MOR binding (Fig. 1, E–H, and supplemental Fig. 1, E–H). DAMGO treatment did not affect the ability of naltrindole to reduce DOR binding but increased the naltrindole-induced increase in MOR binding. DPDPE treatment suppressed the ability of naltrindole to reduce DOR binding but did not alter the effect of naltrindole on MOR binding (supplemental Fig. 1, E–H). These data suggest that, unlike an agonist, which promotes ligand binding of the targeted receptor without any effect on an opposing receptor, an antagonist when given chronically suppresses the binding of the targeted receptor but increases the binding of the opposing receptor.

FIGURE 1.

Opioid receptor antagonist and agonist modulation MOR- or DOR-specific ligand binding in NK cells. Shown are representative saturation curves (A, C, E, and G) and the Bmax (B, D, F, and H) of MOR-specific ligand [3H]DAMGO or DOR-specific ligand [3H]naltrindole. Nontransfected MOR or DOR-transfected (μ-siRNA or δ-SiRNA) RNK16 cells (4 × 106) were treated with naltrexone, naltrindole, or vehicle as well as DAMGO (MOR agonist) or DPDPE (DOR agonist) for the last 24 h. Cells were then harvested and used for measurement of opioid receptor binding. Data are means ± S.E. of six independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, compared with control. a, p < 0.05, compared with naltrexone or naltrindole alone; b, p < 0.05, compared with nontransfected cells.

To examine the role of MOR and DOR interaction in the regulation of ligand binding with the receptor, we determined the effects of MOR and DOR antagonists and agonists on the binding of a DO- or MOR-specific ligand on RNK16 cells in which MOR or DOR gene was knocked down by siRNA. Very little or no binding of MOR to [3H]DAMGO was observed for MOR gene-deficient cells regardless of the single or combined antagonist or agonist treatments (Fig. 1). Similarly, very low binding of DOR to [3H]naltrindole was observed for DOR-deficient cells irrespective of agonist and/or antagonist treatments (Fig. 1). In the MOR-deficient RNK16 cells, MOR antagonist naltrexone was not able to increase DOR ligand binding (supplemental Fig. 1). Similarly, in the DOR-deficient RNK16 cells, DOR antagonist naltrindole was not able to increase MOR ligand binding (supplemental Fig. 1).

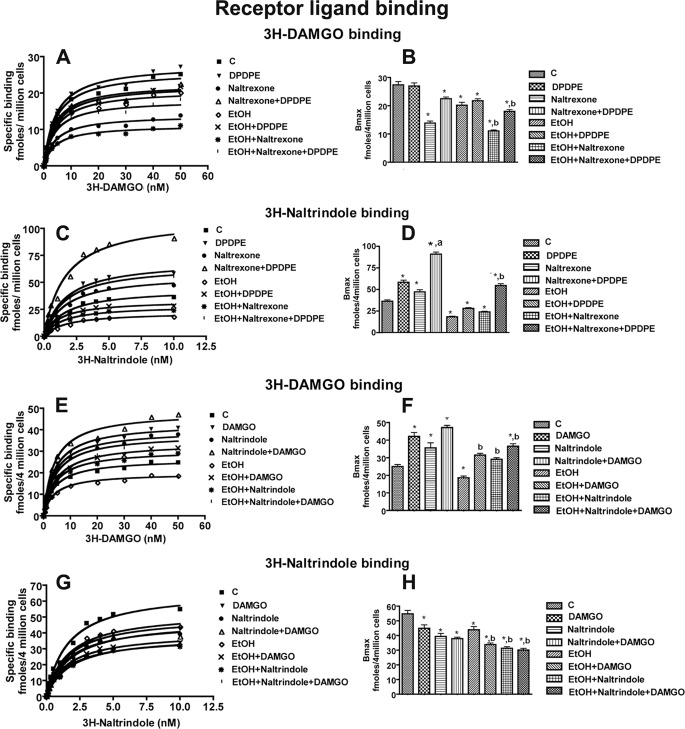

We also tested the effects of ethanol on DOR and MOR interaction. Because ethanol is known to suppress the ligand binding ability of both MOR and DOR in splenocytes (9), the possibility arose that the ability of an antagonist to enhance opposite receptor binding efficacy will be suppressed by ethanol treatment. To test this, we evaluated ethanol effects on agonist and antagonist-modulated ligand binding to DOR and MOR in RNK16 cells. Ethanol treatment for 72 h markedly suppressed (51%) ligand binding to DOR and moderately suppressed (26%) ligand binding to MOR in RNK16 cells (Fig. 2). Ethanol treatment also suppressed the effect of naltrexone with or without DPDPE as well as the effect of naltrindole with or without DAMGO on the ligand binding to MOR and DOR. Together these data suggest that the opposing receptor binding efficacy-enhancing action of an antagonist possibly depends upon its ability to suppress the expression of the targeted receptor, which is preventing the ligand-binding ability of the opposing receptor.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of ethanol on opioid receptor antagonist- and agonist-modulated MOR- and DOR-specific ligand binding in NK cells. Shown are representative saturation curves (A, C, E, and G) and the Bmax (B, D, F, and H) of MOR-specific ligand [3H]DAMGO or DOR-specific ligand [3H]naltrindole. RNK16 cells (4 × 106) were treated with ethanol (50 mm) or vehicle in combination with DOR and MOR antagonists and agonists as described in Fig. 1. Cells were then harvested and used for measurement of opioid receptor binding. Data are mean ± S.E. of six independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, compared with control. a, p < 0.05, compared with naltrexone or naltrindole alone; b, p < 0.05, compared with ethanol alone.

Dimerization of MOR and DOR in NK Cells

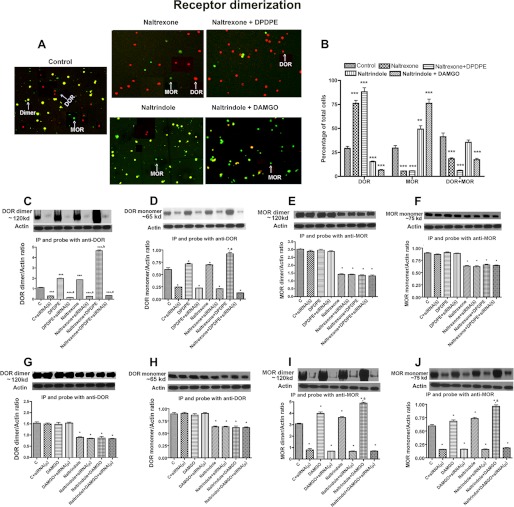

To test whether feedback interaction between these two opioid receptors requires physical association between them, we determined the changes in the immunoreactivity of MOR and DOR proteins following treatments with an antagonist alone or in combination with an agonist. We found that in NK cells the immunoreactivity of MOR and DOR was present in various sizes (possibly due to the presence of receptor monomers and homodimers) and was often colocalized (possibly due to the presence of receptor heterodimers) (Fig. 3A). Treatment with naltrexone reduced the percentage of NK cells stained for MOR only and doubly stained for both MOR and DOR, although it increased the percentage of cells stained for DOR only (Fig. 3, A and B). When combined with a δ agonist DPDPE, the ability of naltrexone to increase DOR and to suppress MOR staining and MOR-DOR double staining was enhanced. Treatment with naltrindole, a DOR antagonist, reduced the percentage of NK cells stained for DOR as well as for both MOR and DOR but increased the percentage of MOR-stained cells. The MOR agonist, DAMGO, potentiated naltrindole stimulatory effect on MOR and inhibitory effects on DOR and DOR and MOR double labeling. Comparison of these histochemical data with those of the ligand binding of the receptor data (Fig. 1) identified an interesting association, an increase in the level of a receptor increases the ligand binding of this receptor, although an increase in the level of two receptors in a single cell reduces the ligand binding of both receptors. These histochemical data show the presence of both MOR and DOR either alone or together in NK cells and provide support for the existence of the receptor monomers and dimers possibly controlling receptor ligand binding efficacy.

FIGURE 3.

Opioid receptor antagonist and agonist modulation of MOR and DOR dimerization in NK cells. Shown are immunohistochemically detected (A and B) or biochemically detected (C–J) opioid receptor homodimers or heterodimers in RNK16 cells. Cells were grown in cultures and treated as described in Fig. 1. Some of these cultures were then harvested and used for double immunostaining using μ- or δ-specific antibody. Red, DOR; green, MOR; yellow, MOR + DOR. Other cultures were harvested and used for measurements of opioid receptor dimerization by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot. Data are mean ± S.E. of four experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, compared with control. a, p < 0.05, compared with naltrexone or naltrindole alone; b, p < 0.05, compared with nontransfected cells.

To quantitate the levels of receptor monomers and dimers of MOR and DOR in NK cells, cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated using either DOR or MOR antibodies and then separated by SDS-PAGE the receptor monomer and by nondenaturing gel the receptor dimer. When immunoprecipitated and probed with DOR antibody, untreated RNK16 cells showed a significant amount of DOR dimers and monomers (Fig. 3, C, D, G, and H). Similarly, when immunoprecipitated and probed with MOR antibody, untreated RNK16 cells showed a significant amount of MOR dimers and monomers (Fig. 3, E, F, I, and J), Naltrexone or DPDPE alone increased the formation of both DOR monomers and dimers. Naltrexone and DPDPE combination treatment increased the amount of DOR monomers and dimers more than those achieved by treatment with these two drugs alone. Naltrindole but not DAMGO treatment reduced the levels of DOR monomers and dimers. In DOR-repressed cells, a low amount of DOR dimers and monomers was detected in blots from both native and SDS gels regardless of the treatment. In DOR-repressed cells, naltrexone and DPDPE did not change the levels of DOR monomers of dimers. Measurements of MOR monomer and dimers levels indicated that naltrindole or DAMGO treatment alone has significant stimulatory effects on these proteins. Naltrindole in combination with DAMGO increased MOR monomer and dimer levels more than those achieved by the treatment alone. DPDPE treatment showed no significant effect on basal or naltrindole-induced changes in MOR monomers and dimers (Fig. 3, E and F). Naltrexone but not DPDPE reduced the levels of MOR monomers and dimers. MOR-repressed cells showed low levels of MOR monomers and dimers and showed no response to naltrindole and/or DAMGO treatments. These results are in agreement with those obtained from histochemical studies, and further support the concept that receptor dimerization may be a process by which MOR and DOR interact to control the ligand binding with the receptor on RNK16 cells.

In the histochemical studies, we noted that a large number of NK cells stained for two receptors, and the number of the cells stained for two receptors decreased following treatment with receptor agonists and antagonists. These data suggest that MOR and DOR antagonists might have altered the level of receptor heterodimers. To test this, RNK16 cells were treated with an opioid receptor antagonist (naltrexone or naltrindole) with or without an opioid agonist (DPDPE or DAMGO), and cell extracts were immunoprecipitated using either DOR or MOR antibodies and then probed for Western blot with the opposite receptor antibodies. Using this approach, we were able to quantitate MOR and DOR heterodimers by nondenaturing gels. The levels of the heterodimers were reduced by the treatment of MOR or DOR antagonists with or without agonists (Fig. 4, E and G).

FIGURE 4.

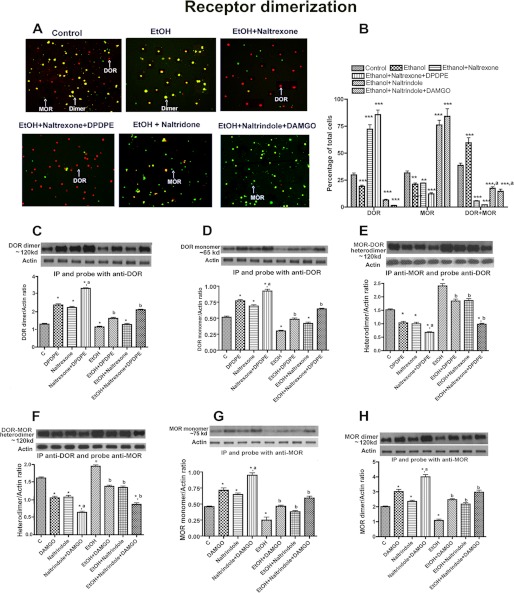

Effect of ethanol on opioid receptor antagonist- and agonist-modulated MOR and DOR dimerization in NK cells. Shown are immunohistochemically detected (A and B) or biochemically detected (C–H) opioid receptor homodimer or heterodimer in RNK 16 cells. Cells were grown in cultures and treated as described in Fig. 2. Some of these cultures were then harvested and used for double immunostaining using μ- or δ-specific antibody. Red, DOR; green, MOR; yellow, MOR + DOR. Other cultures were harvested and used for study of opioid receptor dimerization by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot. Data are mean ± S.E. of four experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 or ***, p < 0.001, compared with control. a, p < 0.05, compared with naltrexone or naltrindole alone; b, p < 0.05, compared with ethanol alone.

In the receptor ligand binding study, we noted that alcohol repressed ligand binding to both DOR and MOR receptors. Hence, the possibility arose that alcohol treatment may have affected protein levels of these receptors. Immunohistochemical localization of the MOR and DOR protein levels in NK cells revealed that alcohol reduced the percentage of NK cells stained for MOR or DOR only, but increased the percentage of double stained for both MOR and DOR (Fig. 4, A and B). Ethanol, when combined with naltrexone or naltrexone and DPDPE, reduced the percentage of NK cells stained for MOR only or double stained for both MOR and DOR, although it increased the percentage of cells stained for DOR only. However, alcohol when combined with naltrindole or naltrindole and DAMGO reduced the percentage of NK cells stained for DOR only or double stained for both MOR and DOR, although it increased the percentage of cells stained for MOR only. These data suggest that ethanol may promote MOR and DOR homodimerization.

Quantification of receptor protein levels, using immunoprecipitation and Western blot, indicated that ethanol treatment decreased protein levels of DOR and MOR monomers and homodimers, although it increased levels of DOR and MOR heterodimers (Fig. 4, C–H). Ethanol enhancing effect on DOR and MOR heterodimerization was partially blocked by naltrexone and DPDPE alone and was completely blocked by the combined treatments of naltrexone and DPDPE. Ethanol-suppressing effects on DOR monomerization and dimerization were antagonized by naltrexone and DPDPE, although its suppressing effects on MOR monomerization and dimerization were antagonized by naltrindole and DAMGO. These data suggest that ethanol suppresses MOR or DOR monomers and dimers by increasing heterodimerization of MOR and DOR receptors, although naltrexone with or without DPDPE or naltrindole with or without DAMGO blocks the effects of ethanol on receptor heterodimerization.

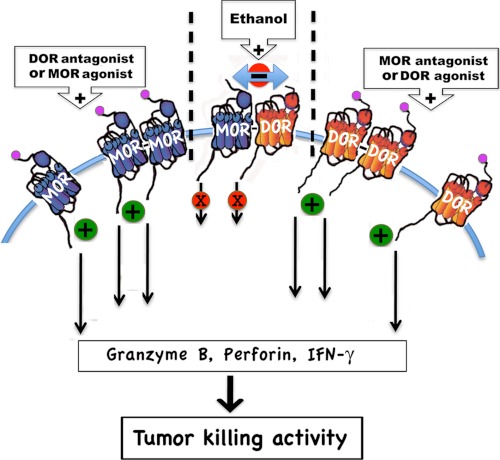

Together these data suggest that an antagonist increases ligand binding of the opposing receptor by decreasing the protein levels of its targeted receptor originally present in a monomeric or heterodimeric form, thereby relieving the opposing receptor forming monomers and homodimers to increase ligand binding. A receptor agonist increases targeted receptor homodimers by suppressing formation of MOR and DOR heterodimers. Ethanol suppresses MOR or DOR monomers and dimers by increasing heterodimerization of these two receptors. The action of ethanol on receptor heterodimerization can be repressed at various levels by a MOR or DOR antagonist with or without an agonist.

Interaction between DOR and MOR in Regulation of Cytolytic Protein Production in NK Cells

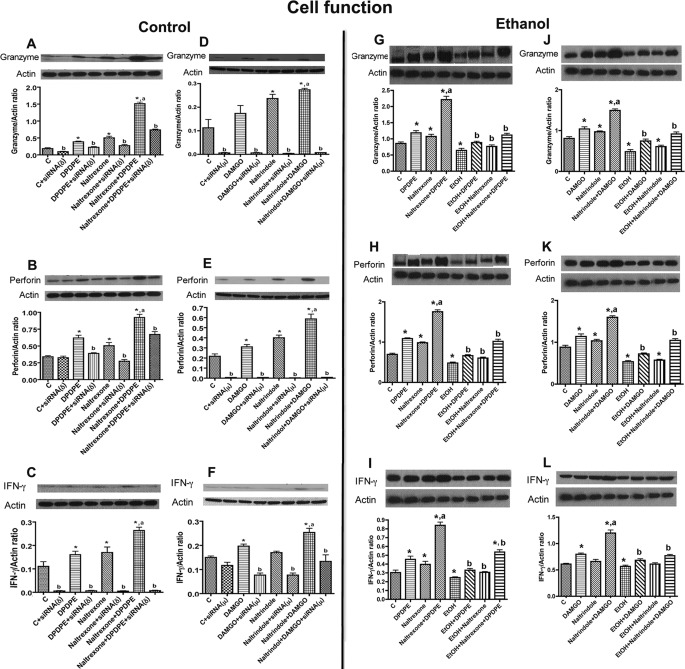

To determine the physiological consequences of altered binding and signaling of DOR or MOR in NK cells, we compared the effects of naltrexone and/or DPDPE and naltrindole and/or DAMGO on the production of cytotoxic factors granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ in control and receptor-deficient RNK16 cells. Treatment with naltrexone or DPDPE alone significantly increased cellular levels of granzyme, perforin, and IFN-γ (Fig. 5, A–C) in NK cells with intact receptors but not in DOR-deficient NK cells. Combined treatment of naltrexone and DPDPE increased the levels of these cytotoxic factors, more than those achieved by each of them alone. Knocking down DOR partially suppressed the naltrexone and DPDPE stimulatory effect on granzyme B and perforin. DOR knockdown cells show low expression of IFN-γ regardless of the single or combined antagonist or agonist treatments. Treatment with naltrindole or DAMGO significantly increased cellular levels of granzyme and perforin (Fig. 5, D and E) in NK cells with intact receptors. Naltrindole moderately increased (did not achieve significance) and DAMGO significantly increased the cellular levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 5F) in NK cells with intact receptors. Combined treatment of naltrindole and DAMG increased the levels of these cytotoxic factors more than those achieved by them alone. MOR knockdown cells show low expression of IFN-γ regardless of the single or combined antagonist or agonist treatments.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of opioid receptor antagonist and agonist modulation of NK cell function (cytotoxic factor productions) in the absence (A–F) or presence of ethanol (G–L). RNK16 cells were treated as described in Figs. 1 and 2 and then harvested and used for measurement of cytotoxic factors (granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ). Data are means ± S.E. of six independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, compared with control. a, p < 0.05, compared with naltrexone or naltrindole alone; b, p < 0.05, compared with nontransfected cells.

Effects of ethanol, with or without MOR and DOR ligands, on the production of cytotoxic factors were determined in control RNK16 cells. Ethanol treatment decreased cellular levels of granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ proteins in RNK16 cells (Fig. 5, G–L). MOR antagonist and DOR agonist suppressed the effects of ethanol on cytotoxic factor productions.

Comparison of the effects of MOR and DOR ligands and ethanol on cellular production of cytotoxic factors, receptor dimerization, and ligand binding of receptors revealed that opioid receptor homodimerization, activated by an opposite receptor antagonist with an agonist, was associated with an increase, and heterodimerization, caused by ethanol, was associated with a decrease in ligand binding of the receptors and the production of cytotoxic factors in RNK16 cells.

In Vivo Interaction between DOR and MOR in Regulation of Ligand Binding in Immune Cells

In vivo studies were conducted to evaluate DOR and MOR interaction in splenocytes. Because splenic cells contain immune cells, including NK cells, and provide the quantity that is required for conducting the receptor binding and functional experiments, we have used splenocytes in the in vivo experiments. In addition, opioid receptors ligand binding and actions were similar both in NK cells and splenocytes (3, 4, 9). In vitro studies showed that naltrexone and DPDPE, alone and in combination, were the most effective in preventing DOR and MOR dimerization and increasing receptor ligand binding. Hence, our investigation of DOR and MOR interaction included only naltrexone and DPDPE treatments. We hypothesized that, as in vitro, chronic ethanol treatment will enhance the interaction between these two receptors to reduce ligand binding on splenocytes that will be reflected in this study. As shown in Fig. 6, A–D, chronic treatment of naltrexone or DPDPE increased DOR ligand binding, but reduced MOR ligand binding on splenocytes of control-fed (PF) animals. Combined treatment of naltrexone and DPDPE showed additive effects on DOR and MOR ligand binding in PF animals. Chronic ethanol treatment reduced the DOR and MOR ligand binding with splenocytes. The inhibitory effect of ethanol on DOR ligand binding was prevented by naltrexone and DPDPE, but the inhibitory effect of ethanol on MOR ligand binding was enhanced by naltrexone and DPDPE. These data suggest that a feedback inhibitory interaction between the constitutively active DOR and MOR control ligand binding with these receptors.

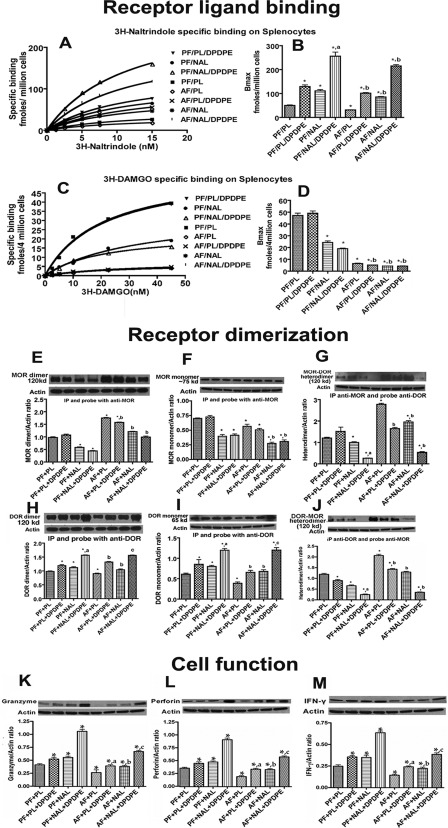

FIGURE 6.

Opioid antagonist and agonist modulation of MOR and DOR ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and cell function in the absence or presence of ethanol in splenocytes in vivo. Shown are representative saturation curves (A and C) and the Bmax (B and D) of DOR-or MOR-specific ligand, opioid receptor homodimers or heterodimers (E–J), and the cellular levels of cytotoxic factors (granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ) in splenocytes (K–M) obtained from spleens of naltrexone (NAL)- or placebo (PL)-treated rats fed an alcohol-containing liquid diet (AF) or PF isocaloric liquid diet. Data are mean ± S.E. of four experiments. *, p < 0.05, compared with PF + PL. a, p < 0.05, compared with naltrexone alone; b, p < 0.05, compared with alcohol-fed alone.

Evidence for Dimerization of MOR and DOR in Splenocytes in Vivo

Splenocyte extracts were immunoprecipitated and probed with MOR antibody, and splenocytes from PF rats showed a significant amount of MOR homodimer and monomer (Fig. 6, E and F). Similarly, when immunoprecipitated and probed with DOR antibody, splenocytes showed a significant amount of DOR dimer and monomers (Fig. 6, H and I). Naltrexone treatment alone decreased the levels of MOR monomers and dimers, although it increased the levels of both DOR monomers and dimers. Naltrexone and DPDPE combination treatment changed the levels of these monomers and dimers more than those achieved by treatment alone. Naltrexone alone decreased the levels of DOR and MOR heterodimers, and these effects were enhanced by DPDPE (Fig. 6, G and J).

Ethanol-enhancing effect on DOR and MOR heterodimerization was partially blocked by naltrexone and DPDPE alone and was reversed by the combined treatments of naltrexone and DPDPE (Fig. 6, G and J). The suppressing effects of ethanol on DOR monomerization and dimerization were antagonized by naltrexone and DPDPE, and its suppressing effects on MOR monomerization and dimerization were antagonized by naltrindole and DAMGO. These data suggest that ethanol suppresses MOR or DOR monomers and dimers by increasing heterodimerization of MOR and DOR receptors, although naltrexone together with DPDPE, or naltrindole together with DAMGO, block the effects of ethanol on receptor heterodimerization.

Interaction between DOR and MOR in Regulation of Cytolytic Protein Production in Splenocytes in Vivo

Physiological consequences of altered binding and signaling of DOR or MOR by naltrexone, DPDPE, and/or ethanol in splenocytes were evaluated. We found that both naltrexone and DPDPE increased the levels of granzyme B, IFN-γ, and perforin in PF rats, and the effects on cytotoxic factor production were enhanced in the combination of these two opioid ligands (Fig. 6, K–M). Chronic ethanol treatment reduced the levels of granzyme B, IFN-γ, and perforin in splenocytes. The inhibitory effect of ethanol on the cytotoxic factors was prevented by naltrexone and DPDPE. Our results suggest that naltrexone increases basal and opioid receptor agonist-induced NK cell function controlling cytotoxic factors in the spleen, and it prevents the inhibitory action of ethanol on the production of these cytotoxic factors. Furthermore, these data suggest that a feedback inhibitory interaction between the constitutively active DOR and MOR controls the receptor function in immune cells.

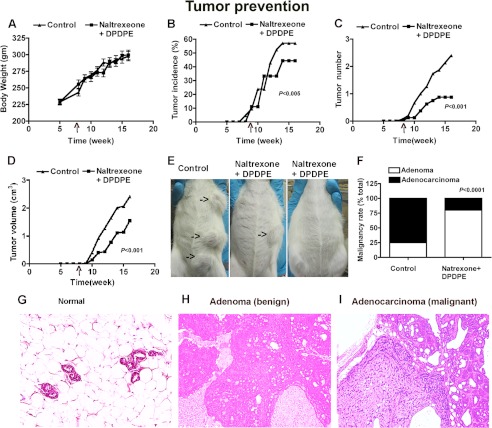

Effects of MOR Antagonist Naltrexone and DOR Antagonist DPDPE in Prevention of Mammary Cancer Growth

Because naltrexone and DPDPE increased the levels of opioid receptors and promoted the production of NK cell cytotoxic factors in the spleen, the possibility is raised that these will increase the ability of NK cells in suppressing tumor growth. To test this possibility, we used NMU to induce mammary cancer in rats (20). Weekly measurements of body weight, tumor number, length, and width for a period of 16 weeks revealed that naltrexone- and DPDPE-treated animals had comparable changes in body weight as in control but had lower tumor incidence, tumor numbers, and tumor volume (Fig. 7, A–D). At the termination of the experiment, whole body inspection revealed that tumors were localized only in mammary glands (Fig. 7E). Tumors from the study were classified by histopathological analysis (Fig. 7, F–I), which showed that control animals had mostly adenocarcinoma, although naltrexone- and DPDPE-treated animals had mostly benign adenoma. Measurements of splenic levels of granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ revealed that animals with naltrexone and DPDPE had higher levels of these cytotoxic factors (granzyme B, control, 0.95 ± 0.05; naltrexone + DPDPE, 1.36 ± 0.04, n = 4, p < 0.05; perforin, control, 0.79 ± 0.03, naltrexone + DPDPE, 1.15 ± 0.04, n = 4, p < 0.05; IFN-γ, control, 0.69 ± 0.04, naltrexone + DPDPE-1.26 ± 0.02, n = 4, p < 0.01). These data suggest that naltrexone and DPDPE increase the production of cytotoxic factors to suppress mammary tumor growth.

FIGURE 7.

Efficacy of opioid antagonist and agonist combined treatment in reduction of mammary tumor growth and progression. Showing changes in body weight (A), percent of rats presenting with tumors each week post-injection (B), average tumor number (C), and average volume of tumor per animal in each group (D) of rats treated with NMU as well as naltrexone and DPDPE or vehicle are shown. Representative whole mount photographs are shown of a vehicle-treated control animal with multiple tumors (shown by arrows) and a naltrexone- and DPDPE-treated animal with a single tumor or without a tumor (E). Tumor malignancy rate (F) and representative histological pictures of a control (G), benign (H), and a malignant tumor (I) are also shown (E–G). The p values obtained from the comparison of two groups are given inside the figures.

DISCUSSION

Opioid peptides, such as β-endorphin and enkephalin, can directly modulate the function of lymphocytes and other cells involved in host defense and immunity (20–22). These endogenous peptides are known to act via MOR and DOR. The detection and signaling of DOR and MOR on lymphocytes have been previously summarized (9, 21, 23). Functional evidence of these receptors on lymphocytes was also recently reviewed (20). Despite the beneficial effects of opioid peptides and their analogs, the use of opioid analogs or opiate receptor ligands in promotion of immune function in alcoholics and other patients with immune deficiencies is limited because of the continuous or repeated exposure to an opioid ligand decreases the sensitivity to the drug and reduces cellular responses (25, 26). Furthermore, psychoactive drugs, including ethanol, alter opiate receptor signaling and function (13).

The mechanisms underlying the response of opioid receptors to endogenous and exogenous ligands after prolonged exposure to opioid receptor antagonists were not well studied. In the cellular model, chronic exposure to MOR or DOR agonists results in several adaptive responses, including receptor desensitization (27), receptor down-regulation (28), receptor internalization (29), receptor association with G protein receptor kinase (30), and adenylyl cyclase supersensitization (31). Chronic treatment with opioid agonists converts the antagonist naloxone and naltriben into inverse agonists on DOR (32). Both DOR and MOR have constitutive activity (14, 32, 33), and this may contribute to the development of adaptive response.

Opioid receptors are members of the large superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (14). Like many G protein-coupled receptors, DOR and MOR are constitutively active, producing spontaneous regulation of G protein and effectors in the absence of agonists (15, 16). It could be that chronic treatment with opioid antagonists increases the affinity of agonists for those opioid receptors that are not occupied by the antagonist, thereby increasing the responsiveness of the receptor to an agonist. However, this view cannot explain the differential responses of the DOR or MOR to naltrexone and naltrindole. We noted an inverse relationship exists between the expression of these opioid receptors in the splenocytes and RNK16 cells. Hence, we tested the possibility that there may exist an intrinsic feedback inhibition of constitutively active MOR on DOR receptor and vice versa. This view is supported by our data showing that an MOR-specific antagonist decreases MOR ligand binding but increases DOR ligand binding. Additionally, a DOR-specific antagonist decreases DOR ligand binding but increases MOR ligand binding. We also found that the interaction between MOR and DOR ligand binding depends on the availability of receptor proteins as down-regulation of the expression of the genes alters the feedback interaction between these two receptors. These data suggest that there might exist a negative feedback interaction between constitutively active MOR and DOR in the spleen.

Opioid receptors are G protein-coupled receptors and they are known to dimerize, often as a form of homodimers within the same group of receptors or heterodimer between two groups of receptors (9, 34–36). Homodimerization of a receptor increases and heterodimerization of two receptors decreases ligand sensitivity. The existence of MOR and DOR monomer, homodimer, and heterodimers has been documented in many nonimmune cells using Western blots and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (37). Our study identified that in NK cells, MOR and DOR both homodimerize and heterodimerize. In a ligand-free in vitro situation, we found that NK cells express both DOR and MOR proteins in the forms of monomer, homodimer, and heterodimer, suggesting that these receptor proteins constitutively express and dimerize without the ligand binding. Following occupation by an agonist, the levels of targeted receptor monomers and dimers are elevated without affecting the opposing receptor. Interestingly, in the chronic presence of an antagonist, the level of targeted receptor decreases and the opposite receptor increases and receptor heterodimerization shifts toward monomerization and/or homodimerization of the opposing receptor. In the functional study, we found a receptor monomerization and/or homodimerization increases and receptor heterodimerization reduces the cell function irrespective of whether it is a MOR or DOR. Together, these data suggest that receptor dimerization mediates the inhibitory feedback interaction between DOR and MOR as well as ligand binding efficacy and signaling.

Previously, it has been shown that ethanol alters protein levels of MOR and DOR, the association of MOR and DOR with G protein receptor kinase, and receptor trafficking (9, 13, 38) in many cells. Our data identified an additional mechanism of ethanol action involving MOR and DOR heterodimerization to reduce receptor signaling in NK cells. Because DOR and MOR provide feedback to each other, dimerization of these receptors possibly contributes to the reduced ligand binding and receptor signaling by chronic ethanol.

The inhibitory feedback interaction between DOR and MOR that we observed appears to be a physiological mechanism by which NK cell functions. This view is supported from our observations that gene knockdown of DOR or MOR not only affects its ligand binding efficacy but also reduces basal production of cytolytic factors in NK cells. Furthermore, the antagonist- and agonist-altered receptors dimerization, ligand-binding efficacy, and cytolytic factor productions mirrored both in vitro and in vivo studies. Additionally, a combined treatment of an antagonist and an opposing receptor agonist was able to maintain enhanced immune function to such an extent to reduce the growth and progression of mammary tumors.

The use of morphine as the opioid of choice has limited the ability as to which type of opioid receptor mediates an immunological response and also for better uses of opioid ligands in managing immune functions. Many investigators choose to study the effects of morphine on immune functions because morphine is an opioid that is given clinically, even though morphine has good affinity for all opioid receptors (24, 39). We have shown here that MOR and DOR constitutively produce and function in innate immune cells, and activation of these receptors leads to increased NK cell functions. We have also shown that DOR and MOR feedback each other by physical association via forming dimers, and dimerization between these receptors possibly contributes to the desensitization of these receptors. Our results indicated that NK cells of ethanol-fed animals were less responsive to opioid activation, and naltrexone administration with or without a DPDPE during ethanol intake reverses the suppressive effects of ethanol on NK cell function by preventing negative feedback interaction of MOR and DOR and formation of heterodimers of these receptors. Furthermore, we found that the opiate antagonist and agonist combination treatment maintains enhanced immune functions for a prolonged period of time and suppresses tumor growth (Fig. 8). Hence, combining an opioid antagonist and agonist may have potential therapeutic value for the treatment of immune incompetence, cancer, and ethanol-dependent diseases.

FIGURE 8.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanisms by which opioid receptor antagonist and agonist and ethanol regulate the negative feedback interaction between DOR and MOR in NK cells to control the tumor killing activity. We propose that MOR and DOR dimerize to inhibit each other's function. We also propose that the agonistic effect of an antagonist might be related to prevention of heterodimerization of DOR and MOR, because long term occupation of the antagonist down-regulates the targeted receptor and thereby increases the availability of the opposing receptor. Furthermore, we propose that increased negative interaction between DOR and MOR via heterodimerization might be a mechanism by which ethanol alters the NK cell response to opioid peptides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Furbeck and Kathleen Roberts for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants 1R21AA016296 and R37AA08757 (to D. K. S.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- NK

- natural killer

- DAMGO

- Tyr-d-Ala-Gly-N-MePhe-Gly-ol

- DPDPE

- [d-Pen2,p-chloro-Phe4,d-Pen5]enkephalin

- DOR

- δ-opioid receptor

- MOR

- μ-opioid receptor

- PF

- pair-fed

- NMU

- N-methyl-N-nitrosourea.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mandler R. N., Biddison W. E., Mandler R., Serrate S. A. (1986) β-Endorphin augments the cytolytic activity and interferon production of natural killer cells. J. Immunol. 136, 934–939 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pruett S. B., Han Y. C., Wu W. J. (1994) A brief review of immunomodulation caused by acute administration of ethanol. Involvement of neuroendocrine pathways. Alcohol Alcohol. Suppl. 2, 431–437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyadjieva N., Dokur M., Advis J. P., Meadows G. G., Sarkar D. K. (2001) Chronic ethanol inhibits NK cell cytolytic activity. Role of opioid peptide β-endorphin. J. Immunol. 167, 5645–5652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyadjieva N., Advis J. P., Sarkar D. K. (2006) Role of β-endorphin, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and autonomic nervous system in mediation of the effect of chronic ethanol on natural killer cell cytolytic activity. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 30, 1761–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dokur M., Chen C. P., Advis J. P., Sarkar D. K. (2005) β-Endorphin modulation of interferon-γ, perforin, and granzyme B levels in splenic NK cells. Effects of ethanol. J. Neuroimmunol. 166, 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dokur M., Boyadjieva N. I., Advis J. P., Sarkar D. K. (2004) Modulation of hypothalamic β-endorphin-regulated expression of natural killer cell cytolytic activity regulatory factors by ethanol in male Fischer-344 rats. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 28, 1180–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brownstein M. J. (1993) A brief history of opiates, opioid peptides, and opioid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5391–5393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shahabi N. A., McAllen K., Matta S. G., Sharp B. M. (2000) Expression of δ-opioid receptors by splenocytes from SEB-treated mice and effects on phosphorylation of MAP kinase. Cell. Immunol. 205, 84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boyadjieva N. I., Chaturvedi K., Poplawski M. M., Sarkar D. K. (2004) Opioid antagonist naltrexone disrupts feedback interaction between μ- and δ-opioid receptors in splenocytes to prevent alcohol inhibition of NK cell function. J. Immunol. 173, 42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leriche M., Méndez M. (2010) Ethanol exposure selectively alters β-endorphin content but not [3H]DAMGO binding in discrete regions of the rat brain. Neuropeptides 44, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarkar D. K., Kuhn P., Marano J., Chen C., Boyadjieva N. (2007) Alcohol exposure during the developmental period induces β-endorphin neuronal death and causes alteration in the opioid control of stress axis function. Endocrinology 148, 2828–2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rasmussen D. D., Boldt B. M., Wilkinson C. W., Mitton D. R. (2002) Chronic daily ethanol and withdrawal. 3. Forebrain pro-opiomelanocortin gene expression and implications for dependence, relapse, and deprivation effect. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 26, 535–546 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saland L. C., Chavez J. B., Lee D. C., Garcia R. R., Caldwell K. K. (2008) Chronic ethanol exposure increases the association of hippocampal μ-opioid receptors with G-protein receptor kinase 2. Alcohol 42, 493–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Law P. Y., Wong Y. H., Loh H. H. (2000) Molecular mechanisms and regulation of opioid receptor signaling. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40, 389–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Merkouris M., Mullaney I., Georgoussi Z., Milligan G. (1997) Regulation of spontaneous activity of the δ-opioid receptor. Studies of inverse agonism in intact cells. J. Neurochem. 69, 2115–2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burford N. T., Wang D., Sadée W. (2000) G-protein coupling of μ-opioid receptors (OP3). Elevated basal signaling activity. Biochem. J. 348, 531–537 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. George S. R., Fan T., Xie Z., Tse R., Tam V., Varghese G., O'Dowd B. F. (2000) Oligomerization of μ- and δ-opioid receptors. Generation of novel functional properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26128–26135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gomes I., Filipovska J., Jordan B. A., Devi L. A. (2002) Oligomerization of opioid receptors. Methods 27, 358–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bidlack J. M., Khimich M., Parkhill A. L., Sumagin S., Sun B., Tipton C. M. (2006) Opioid receptors and signaling on cells from the immune system. J. Neuroimmune. Pharmacol. 1, 260–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De A., Boyadjieva N., Oomizu S., Sarkar D. K. (2002) Ethanol induces hyperprolactinemia by increasing prolactin release and lactotrope growth in female rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 26, 1420–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sharp B. M. (2006) Multiple opioid receptors on immune cells modulate intracellular signaling. Brain Behav. Immun. 20, 9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brogden K. A., Guthmiller J. M., Salzet M., Zasloff M. (2005) The nervous system and innate immunity. The neuropeptide connection. Nat. Immunol. 6, 558–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharp B. M. (2003) Opioid receptor expression and intracellular signaling by cells involved in host defense and immunity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 521, 98–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ueda H., Ueda M. (2009) Mechanisms underlying morphine analgesic tolerance and dependence. Front. Biosci. 14, 5260–52672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prather P. L., Tsai A. W., Law P. Y. (1994) μ- and δ-opioid receptor desensitization in undifferentiated human neuroblastoma SHSY5Y cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 270, 177–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christie M. J. (2008) Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids. Tolerance, withdrawal, and addiction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 384–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovoor A., Nappey V., Kieffer B. L., Chavkin C. (1997) μ- and δ-opioid receptors are differentially desensitized by the coexpression of β-adrenergic receptor kinase 2 and β-arrestin 2 in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27605–27611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chakrabarti S., Yang W., Law P. Y., Loh H. H. (1997) The μ-opioid receptor down-regulates differently from the δ-opioid receptor. Requirement of a high affinity receptor/G protein complex formation. Mol. Pharmacol. 52, 105–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keith D. E., Murray S. R., Zaki P. A., Chu P. C., Lissin D. V., Kang L., Evans C. J., von Zastrow M. (1996) Morphine activates opioid receptors without causing their rapid internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19021–19024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Z. J., Wang L. X. (2006) Phosphorylation: a molecular switch in opioid tolerance. Life Sci. 79, 1681–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharma S. K., Klee W. A., Nirenberg M. (1975) Dual regulation of adenylate cyclase accounts for narcotic dependence and tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 3092–3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu J. G., Prather P. L. (2002) Chronic agonist treatment converts antagonists into inverse agonists at δ-opioid receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 302, 1070–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Law P. Y., Erickson-Herbrandson L. J., Zha Q. Q., Solberg J., Chu J., Sarre A., Loh H. H. (2005) Heterodimerization of μ- and δ-opioid receptors occurs at the cell surface only and requires receptor-G protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11152–11164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Balenga N. A., Henstridge C. M., Kargl J., Waldhoer M. (2011) Pharmacology, signaling, and physiological relevance of the G protein-coupled receptor 55. Adv. Pharmacol. 62, 251–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Rijn R. M., Whistler J. L., Waldhoer M. (2010) Opioid-receptor-heteromer-specific trafficking and pharmacology. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 10, 73–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rozenfeld R., Abul-Husn N. S., Gomez I., Devi L. A. (2007) An emerging role for the δ-opioid receptor in the regulation of μ-opioid receptor function. Scientific World J. 7, 64–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang D., Sun X., Bohn L. M., Sadée W. (2005) Opioid receptor homo- and heterodimerization in living cells by quantitative bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 2173–2184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen F., Lawrence A. J. (2000) Effect of chronic ethanol and withdrawal on the μ-opioid receptor- and 5-hydroxytryptamine(1A) receptor-stimulated binding of [35S]guanosine-5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate in the fawn-hooded rat brain. A quantitative autoradiography study. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 293, 159–165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stefano G. B., Kream R. M., Esch T. (2009) Revisiting tolerance from the endogenous morphine perspective. Med. Sci. Monit. 15, RA189–RA198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.