Background: Autophagy is an essential physiological process that is tightly regulated.

Results: Ksp1 is a negative regulator of autophagy that activates the Tor complex 1 (TORC1), and Ksp1 function is regulated by protein kinase A (PKA).

Conclusion: Ksp1 integrates signaling between PKA and TORC1.

Significance: Our work implicates the Ksp1 kinase as part of the TORC1 network for regulating autophagy.

Keywords: Autophagy, Lysosomes, Stress, Yeast, Yeast Genetics, Kinase

Abstract

Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy) is a bulk degradation system conserved in all eukaryotes, which engulfs cytoplasmic components within double-membrane vesicles to allow their delivery to, and subsequent degradation within, the vacuole/lysosome. Autophagy activity is tightly regulated in response to the nutritional state of the cell and also to maintain organelle homeostasis. In nutrient-rich conditions, Tor kinase complex 1 (TORC1) is activated to inhibit autophagy, whereas inactivation of this complex in response to stress leads to autophagy induction; however, it is unclear how the activity of TORC1 is controlled to allow precise adjustments in autophagy activity. In this study, we performed genetic analyses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to identify factors that regulate TORC1 activity. We determined that the Ksp1 kinase functions in part as a negative regulator of autophagy; deletion of KSP1 facilitated dephosphorylation of Atg13, a TORC1 substrate, which correlates with enhanced autophagy. These results suggest that Ksp1 down-regulates autophagy activity via the TORC1 pathway. The suppressive function of Ksp1 is partially activated by the Ras/cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), which is another negative regulator of autophagy. Our study therefore identifies Ksp1 as a new component that functions as part of the PKA and TORC1 signaling network to control the magnitude of autophagy.

Introduction

Cells have evolved mechanisms to facilitate an appropriate response to changing nutritional conditions. Autophagy, so-called “self-eating,” is one of the primary means of adaptation and is conserved in all eukaryotes, from yeast to human (1). By means of autophagy, cells degrade their own components to supply a minimum nutritional source for survival when nutrients in the environment are depleted. In mammals, the induction of autophagy is associated with a wide range of developmental and pathophysiological conditions, including cellular differentiation, cancer, neurodegeneration, inflammation, and aging, although the role played by autophagy is not fully understood. Under starvation conditions, autophagy is a nonselective process, sequestering bulk cytoplasm into double-membrane autophagosomes that subsequently fuse with the lysosome/vacuole, allowing the cargo to be degraded and the resulting constituents to be recycled. However, there are also many types of selective autophagy, which are used to target invasive microbes, deliver zymogens to the vacuole, or degrade damaged or superfluous organelles. The latter is seen, for example, with the selective elimination of damaged or unnecessary mitochondria and peroxisomes, through processes termed mitophagy and pexophagy, respectively (2, 3). Thus, autophagy functions as a cytoprotective mechanism, not only supplying macromolecular building blocks during nutritional stress but also to eliminate unwanted cellular material.

The mechanism of autophagosome formation provides tremendous flexibility in terms of cargo capacity. Accordingly, autophagy is the primary means used by cells for the degradation of entire organelles; however, this capacity also carries substantial risk, as excessive autophagy is likely to be deleterious. Therefore, it is critical for cells to maintain appropriate levels of autophagy, as either too little or too much can be harmful. The induction of autophagy is tightly regulated by various kinases and phosphatases. The best characterized of these regulatory components is the rapamycin-sensitive Tor complex 1. In nutrient-rich conditions, TORC1 inhibits autophagy via direct phosphorylation of the autophagy-related (Atg) protein Atg13 at multiple Ser residues; the hyperphosphorylation of Atg13 may lead to its dissociation from the Atg1 kinase complex, resulting in the suppression of autophagy (4, 5). The inhibition of TORC1, either by nitrogen starvation or rapamycin treatment, leads to dephosphorylation of Atg13, and the induction of autophagy. TORC1 is highly conserved in all eukaryotes and plays a major role in the regulation of many cellular processes, such as cell growth and transcription, as well as autophagy, by responding to changes in the nutritional state. However, despite the fact that the connection between TORC1 and autophagy was made more than a decade ago (6), it is still largely unknown as to how TORC1 senses the nutrient conditions and how TORC1 activity itself is regulated.

Many studies have been carried out to address this issue, including large scale screens for drugs and proteins that modulate TORC1 activity. In yeast, some of the downstream effectors of TORC1 that participate in autophagy regulation have been identified, including Tap42 and a protein phosphatase 2A (7), and as mentioned above, TORC1 also directly phosphorylates Atg13 (5). In contrast, the upstream factors that control TORC1 are less defined. The Ras-PKA signaling pathway may be connected to TORC1 to suppress autophagy (8) but may also function independently of TORC1 (9); however, these studies suggest that it is unlikely that Ras-PKA acts directly upstream of TORC1. In contrast, Vam6 acts as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the EGO complex, which directly activates TORC1 in response to the presence of amino acids (10). However, it is likely that additional regulatory components modulate TORC1 activity.

Recent microarray-based expression profiling suggested that autophagy may be physiologically connected to yeast pseudohyphal growth (PHG)2 to suitably adjust the nutritional state of the cell (11); yeast cells that experience decreasing environmental nitrogen will initially form pseudohyphae to seek out additional nutrient sources, but if this is unsuccessful, or if the nitrogen level drops further, autophagy is initiated. Inhibition of autophagy by disrupting ATG genes results in increased PHG at higher concentrations of available nitrogen source than would normally induce this process.

In this study, we examined the function of the Ser/Thr kinase Ksp1 for the regulation of autophagy. From a previous large scale screen, Ksp1 was reported to be involved in PHG (12); however, its physiological function is largely uncharacterized. Here, we determined that it is a negative regulator of autophagy. Our data suggest that Ksp1 suppresses the induction of autophagy by activating the TORC1 pathway. In addition, mutagenesis of phosphorylation sites on Ksp1 indicates that this kinase is activated by PKA. Thus, Ksp1 represents a new component that regulates autophagy via the TORC1 complex.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Media

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Gene deletions were performed by a PCR-based procedure. Yeast strains were grown or incubated in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose), YPGal (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% galactose), synthetic medium (SMD; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, and auxotrophic amino acids, and vitamins as required), or starvation medium (SD-N; 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate and amino acids, 2% glucose, and vitamins as required). Rapamycin (Fermentek, Jerusalem, Israel) was used at each indicated final concentration.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| CWY230 | SEY6210 vac8Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY5 | WLY176 ksp1Δ::Ble | This study |

| MUY7 | ZFY202 fus3Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY16 | ZFY202 ksp1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| MUY19 | ZFY202 ksp1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MUY20 | ZFY202 atg13Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| MUY21 | MUY16 KSP1-WT::URA3 | This study |

| MUY22 | MUY16 KSP1-K47D::URA3 | This study |

| MUY23 | MUY16 KSP1-S827A::URA3 | This study |

| MUY24 | MUY16 KSP1-S624,827A::URA3 | This study |

| MUY25 | MUY16 KSP1-S624,827,883,884A::URA3 | This study |

| MUY27 | MUY16 KSP1-S827D::URA3 | This study |

| MUY28 | MUY16 KSP1-S624A::URA3 | This study |

| MUY29 | ZFY202 bcy1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MUY32 | MUY16 bcy1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MUY37 | ZFY202 kss1Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY38 | ZFY202 sks1Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY39 | ZFY202 atg1Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY40 | MUY19 atg13Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY52 | ZFY202 ksp1Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY53 | ZFY202 atg1Δ::URA3 | This study |

| MUY54 | ZFY202 atg1Δ::URA3 ksp1Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY55 | CWY230 ksp1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MUY59 | SEY6210 ksp1Δ::Kan | This study |

| MUY60 | TKYM67 ksp1Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| MUY101 | W303-1B atg1Δ::Kan ATG9-3×GFP::URA3 RFP-APE1::LEU2 | This study |

| MUY102 | MUY101 ksp1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| SEY6210 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 | 37 |

| TKYM67 | SEY6210 PEX14-GFP::Kan | 38 |

| TKYM72 | SEY6210 atg1Δ::HIS5 S.p. PEX14-GFP::Kan | 38 |

| W303-1B | MATα ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | 39 |

| WHY1 | SEY6210 atg1Δ::HIS5 S.p. | 16 |

| WLY105 | SEY6210 atg27Δ::HIS3 ATG9-3×GFP::URA3 RFP-APE1::LEU2 | 29 |

| WLY176 | SEY6210 pho13Δ pho8Δ60::HIS3 | 40 |

| WLY192 | SEY6210 pho13Δ::kan pho8Δ60::URA atg1Δ::HIS3 | 40 |

| ZFY202 | W303-1B pho13Δ pho8Δ60 | 41 |

Plasmids

The plasmids YEp351(ATG13), p416GAL1(ATG13-WT), and p416GAL1(ATG13-S348A, S437A, S438A, S496A, S535A, S541A, S646A, and S649A (8SA)) have been described previously (4, 5). GFP-ATG8(416) (13), Atg9-3×GFP(306) (15), and red fluorescent protein-tagged Ape1 (RFP-Ape1(305)) (16) were constructed as described previously. A plasmid encoding the full-length Ksp1 protein with the endogenous promoter and terminator was generated by PCR amplification of genomic DNA and cloned into the pRS406 vector. This plasmid was subsequently used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis. Each resulting plasmid was linearized with NcoI to direct integration into the chromosome at the URA3 locus of the MUY16 (ksp1Δ) strain.

Immunoblotting

Yeast cells were grown in YPD medium at 30 °C to early log phase, and rapamycin was added to each culture to inhibit TORC1 activity. For starvation conditions, cells were shifted to SD-N medium. For GAL1-driven expression of Atg13, cells were shifted to YPGal at A600 = 0.8 and grown for 4 h. At the indicated times, cells were collected, and proteins were precipitated by addition of TCA. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with appropriate antiserum or antibodies.

Microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, yeast cells expressing fusion proteins with fluorescent tags were grown to the early log phase and starved with SD-N for 2 h before imaging. Cells were visualized with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) with DeltaVision (Spectris; Applied Precision) using a camera (CoolSNAP HQ; Photometrics) fitted with differential interference contrast optics. Images were taken using a ×100 objective at the same temperature and in the same medium in which the cells were cultured. 12 z-section images were collected and were deconvolved using SoftWoRx software (Applied Precision). Images were prepared in Adobe Photoshop.

Assay for Bulk Autophagy

For monitoring bulk autophagy, the alkaline phosphatase activity of Pho8Δ60 (17, 18) and processing of GFP-Atg8 (13) were assessed according to the previously reported protocols.

Assays for Specific Autophagy

Proteolytic processing of the precursor form of Ape1 (prApe1) was monitored according to a previously reported procedure (19). Cells were grown in SMD medium and collected at A600 = 0.8. For analyzing pexophagy, the processing of Pex14-GFP was monitored according to a previously reported procedure (19). Briefly, cells were grown in SGd medium containing 3% glycerol for 12 h and incubated for 4 h after the addition of yeast extract and peptone into the medium. The cells were then shifted to YTO medium containing 0.1% oleic acid for 19 h before starvation. Proteins were precipitated with 10% TCA and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot with anti-YFP antibody.

RESULTS

Ksp1 Is a Negative Regulator of Autophagy

A physiological connection between autophagy and yeast PHG was suggested from microarray-based expression profiling (11). Because of this interrelationship, we decided to examine the role of kinases that are involved in the induction of PHG for a possible role in the regulation of autophagy. By means of kinase screening for differential localization during PHG, six kinases/kinase regulatory subunits (Bcy1, Fus3, Ksp1, Kss1, Sks1, and Tpk2) that localize predominantly to the nucleus during PHG were identified (12). Deletion of KSP1, KSS1, and TPK2 results in decreased PHG, whereas the fus3 mutant is hyperfilamentous. Deletion of BCY1 and SKS1 does not affect PHG. Because we already know that Tpk2 and Bcy1 are catalytic and regulatory subunits of PKA, which negatively regulates autophagy, we determined whether deletions of the four remaining genes affected autophagy. We used the Pho8Δ60 assay (18), which measures autophagy-dependent activation of an altered alkaline phosphatase marker. Briefly, Pho8Δ60 activity was monitored in strains lacking PHO13 and in which the PHO8 gene was replaced with pho8Δ60, encoding a cytosolic variant of the zymogen alkaline phosphatase. This altered form of the protein was not able to enter the endoplasmic reticulum and remained in the cytosol; vacuolar delivery by bulk autophagy resulted in activation of the zymogen, which is measured by an increase in enzymatic activity.

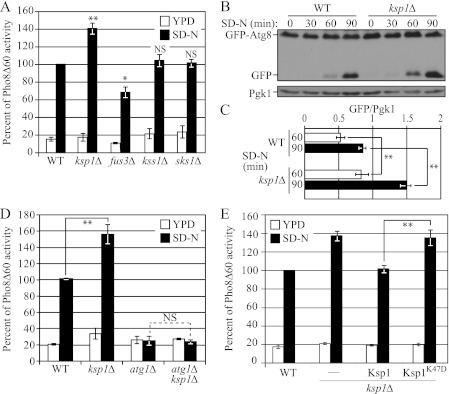

Wild-type cells displayed a background level of Pho8Δ60-dependent alkaline phosphatase activity in nutrient-rich (YPD) conditions and a substantial increase when cells were shifted to nitrogen starvation (SD-N) conditions (Fig. 1A). Under autophagy-inducing conditions, the ksp1Δ cells showed a significant increase of Pho8Δ60 activity (∼40%) above the wild-type cells (Fig. 1A). In contrast, fus3Δ cells showed an ∼30% decrease in activity in starvation conditions and a small, but reproducible, decrease in growing conditions. It is worth noting that the effects seen with the deletion of these two genes are exactly the opposite as seen for their role in PHG, i.e. the deletion of KSP1 has a negative effect for PHG but a positive effect for autophagy, whereas the FUS3 deletion has a positive effect for PHG, but a negative effect for autophagy. We extended our analysis of nonspecific autophagy using the Pho8Δ60 assay in another strain background, comparing it with wild-type and atg1Δ cells. The results were consistent, and the ksp1Δ cells showed a significant increase in activity relative to the wild type, supporting our hypothesis that Ksp1 has a suppressive role in autophagy (supplemental Fig. S1); as expected, cells lacking ATG1, an essential gene for autophagy induction, did not induce autophagy in starvation conditions. The deletion of the other two genes, KSS1 and SKS1, did not result in a significant change in Pho8Δ60 activity (Fig. 1A). Fus3, as well as Kss1, is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family of serine/threonine-specific kinases and is involved in mating as well as PHG (12, 20). The function of Ksp1, however, is currently unknown. Accordingly, we decided to focus our analysis on the Ksp1 kinase, which appeared to have a negative regulatory role in autophagy.

FIGURE 1.

Ksp1 has a suppressive role in autophagy. A, comparison of the Pho8Δ60 activities between the wild-type and mutant strains in the W303-1B background. Wild-type (ZFY202), ksp1Δ (MUY16), fus3Δ (MUY7), kss1Δ (MUY37), and sks1Δ (MUY38) cells expressing Pho8Δ60 were grown in YPD and shifted to nitrogen starvation (SD-N) medium for 4 h. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells treated with SD-N, which was set to 100%. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (S.D.) of at least three independent experiments (in this and subsequent panels). **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; NS, difference was not significant. B, processing of GFP-Atg8 by autophagy was analyzed. Wild-type (ZFY202) and ksp1Δ (MUY52) cells expressing GFP-Atg8 were grown in SMD and shifted to nitrogen starvation (SD-N) medium for the indicated times. Protein extracts were precipitated with TCA and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-YFP antibody (this antibody detects GFP). C, quantification of the GFP-Atg8 processing assay. The ratio of GFP/Pgk1 at the 60- and 90-min time points from the data in B was determined. D, comparison of the Pho8Δ60 activities between the wild-type and mutant strains in the W303-1B background. Wild-type (ZFY202), ksp1Δ (MUY52), atg1Δ (MUY53), and atg1Δ ksp1Δ (MUY54) cells in a Pho8Δ60 strain background were grown in YPD and shifted to nitrogen starvation (SD-N) medium for 4 h. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells treated with SD-N, which was set to 100%. E, comparison of the Pho8Δ60 activities between the wild-type and mutant strains in the W303-1B background. Wild-type (ZFY202), ksp1Δ (MUY16), or ksp1Δ cells expressing a chromosomally integrated wild-type Ksp1 (MUY21) or the kinase-inactive Ksp1 mutant, Ksp1K47D (MUY22), in a Pho8Δ60 strain background were grown in YPD and shifted to nitrogen starvation (SD-N) medium for 4 h. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (S.D.) of at least three independent experiments.

To extend the analysis of autophagy in wild-type and ksp1Δ cells, we utilized the GFP-Atg8 processing assay (Fig. 1B). Atg8 initially lines both sides of the phagophore, the precursor to the sequestering autophagosome. Upon autophagosome completion, Atg8 is removed from the surface, whereas the Atg8 present on the inner vesicle is transported into the vacuole inside the autophagic body (the single-membrane vesicle that results from the fusion of an autophagosome with the vacuole). Atg8 is degraded after lysis of the autophagic body, whereas the GFP moiety of a GFP-Atg8 chimera is relatively resistant to proteolysis. Accordingly, monitoring free GFP processed from GFP-Atg8 reflects the level of autophagy (13). At 60 min after the induction of autophagy, a free GFP band could be seen in the wild-type strain, and this increased with additional time in starvation conditions (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the Pho8Δ60 assay, a stronger GFP signal was observed in the ksp1Δ cells compared with the wild type at the 60- and 90-min time points. Quantification of the ratio of free GFP/Pgk1 (a loading control) at 60 and 90 min revealed values of 0.5 and 0.9 in the wild type, versus 0.8 and 1.5 in the ksp1Δ cells, corresponding to an ∼60% increase in the latter (Fig. 1C).

Next, we verified that the observed increase of the Pho8Δ60-dependent alkaline phosphatase activity in the ksp1Δ cells was due to an increase of autophagy. Accordingly, we assessed the Pho8Δ60 activity in the atg1Δ background, in which the induction of autophagy is completely blocked. As expected, the deletion of KSP1 did not lead to an increase of the Pho8Δ60 activity in the atg1Δ background (Fig. 1D), indicating that the increase in activity seen in the ksp1Δ strain depended on canonical autophagy machinery.

Finally, we confirmed that the increase of autophagy in the ksp1Δ cells was due to the disruption of the KSP1 gene. The wild-type gene with the endogenous promoter was introduced into the genome of the ksp1Δ strain, and we found that the Pho8Δ60 activity was restored to the wild-type level (Fig. 1E), confirming that it was the deletion of KSP1 that caused the significant increase in autophagy. We also examined whether the kinase activity of Ksp1 was responsible for its negative role. For this purpose, we introduced the gene encoding the Ksp1K47D kinase-inactive mutant instead of the wild-type KSP1 gene into the genome of the ksp1Δ cells and assessed the Pho8Δ60 activity. In this case, the phenotype of the ksp1Δ cells was not complemented, and the Pho8Δ60 activity was essentially the same as that of the ksp1Δ cells (Fig. 1E). These results suggested that the kinase activity of Ksp1 has an inhibitory role in autophagy.

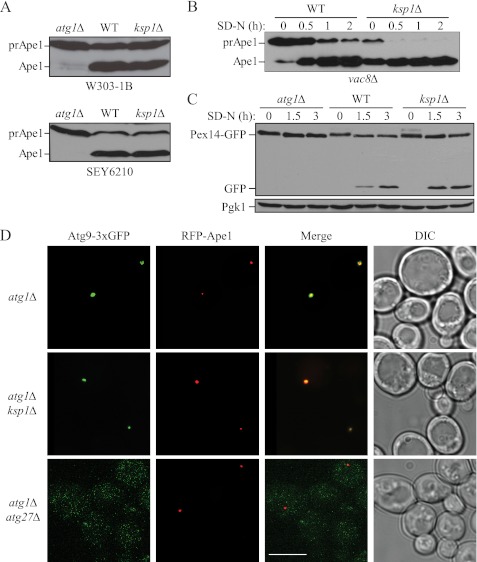

Ksp1 Is Not Required for Selective Types of Autophagy or Atg9 Trafficking

Nonselective autophagy and selective autophagic processes, such as the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway and pexophagy (the selective autophagic degradation of peroxisomes (21)), share most of the same core autophagy-related proteins that are recruited to the phagophore assembly site (PAS) and are involved in the nucleation of the sequestering autophagosomes/Cvt vesicles (22). Therefore, we examined whether the deletion of KSP1 also affects the Cvt pathway. We assessed the Cvt pathway by monitoring the maturation of the vacuolar resident hydrolase aminopeptidase I (Ape1), the primary Cvt cargo component. In atg1Δ cells, the precursor form of Ape1 that contains a propeptide cannot be processed to the mature form, because both the Cvt and autophagy pathways are blocked (Fig. 2A). In wild-type cells we detected a mixture of the precursor and mature forms of Ape1, and a similar result was seen with the ksp1Δ cells in either the W303-1B or SEY6210 background strain (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that Ksp1 is not required for a functional Cvt pathway.

FIGURE 2.

Ksp1 is not required for selective autophagy or Atg9 trafficking. A, the Cvt pathway is normal in the absence of Ksp1. The processing of the Cvt pathway marker protein prApe1 was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Ape1 antiserum in wild-type (ZFY202 and SEY6210), ksp1Δ (MUY16 and MUY59), and atg1Δ (MUY39 and WHY1) cells in the W303-1B and SEY6210 backgrounds. The positions of precursor Ape1 (prApe1) and mature Ape1 (Ape1) are indicated. B, selective import of prApe1 by autophagy is enhanced in cells lacking Ksp1. Wild-type (vac8Δ; CWY230) and ksp1Δ cells in the vac8Δ background were grown to mid-log phase in YPD and then shifted to SD-N for the indicated times. At each time point, samples were removed, and the protein extracts were analyzed by immunoblot using anti-Ape1 antiserum. C, analysis of pexophagy in ksp1Δ cells. Wild-type (TKM67), ksp1Δ (MUY60), and atg1Δ (TKYM72) cells were grown in oleic acid-containing medium for 19 h and then shifted to SD-N for the indicated times. Samples were collected, and Pex14-GFP processing was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-YFP antibody. Pgk1 served as a loading control. D, Ksp1 acts prior to Atg9 trafficking in the step of autophagosome formation. The anterograde movement of Atg9–3×GFP to the PAS was monitored by fluorescence microscopy using RFP-Ape1 as a marker of the PAS. Wild-type (MUY101), ksp1Δ (MUY102), and atg27Δ (WLY105) cells expressing these fluorescent proteins in an atg1Δ background were grown in YPD and shifted to SD-N for 2 h. Scale bar, 15 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast.

Precursor Ape1 is delivered to the vacuole by the Cvt pathway when cells are growing in rich medium, but autophagy is utilized for this transport process under starvation conditions (23). Import is selective in either case because it relies on a receptor (Atg19) and adaptor/scaffold (Atg11) (24). In the absence of Vac8, the Cvt pathway-dependent import of prApe1 is completely blocked; however, the transport defect is suppressed when cells are shifted to starvation conditions (25). Thus, the vacuolar delivery and processing of prApe1 in a vac8Δ strain provide another method for assessing selective autophagy under starvation conditions. As expected, in vac8Δ cells prApe1 accumulated prior to the induction of autophagy, but the precursor was mostly processed to the mature form after shifting the cells to starvation conditions for 1 h (Fig. 2B). In contrast, in ksp1Δ vac8Δ cells the majority of Ape1 was present in the mature form even in rich medium conditions and the remainder was processed within 30 min, suggesting that TORC1 was not fully active resulting in partial autophagy induction prior to starvation.

Additionally, we examined another type of selective autophagy, pexophagy, by monitoring the processing of Pex14-GFP; similar to the GFP-Atg8 processing assay, autophagic delivery of Pex14-GFP to the vacuole results in cleavage of the chimera and the generation of free GFP. In an atg1Δ strain, the processing of Pex14-GFP was completely blocked (Fig. 2C). In contrast, in the wild-type and ksp1Δ strains, Pex14-GFP was processed after starvation. The processing of Pex14-GFP was partially accelerated in the ksp1Δ strain compared with the wild type, similar to the result with the GFP-Atg8 processing assay (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that Ksp1 does not play a significant role in regulating the specific transport of cargo into the vacuole by selective autophagy. Rather, Ksp1 seems to be involved in the regulation of nonselective autophagy.

We were next interested in determining the step in which Ksp1 acts to regulate autophagy. The primary morphological event of this process is the formation of the double-membrane autophagosome, and one of the key proteins involved in autophagosome formation is Atg9. During autophagy, Atg9 cycles from peripheral sites in the cell (termed Atg9 reservoirs or tubulovesicular clusters (26)) to the PAS, putatively to deliver membrane that allows expansion of the phagophore. To determine whether Ksp1 acts to regulate Atg9 movement, we carried out the transport of Atg9 after knocking out ATG1 assay, which can be used to monitor the cycling of Atg9 between the PAS and peripheral sites (13). In an atg1Δ background, Atg9 is restricted at the PAS as a single dot because the retrograde movement of Atg9 from the PAS to the peripheral sites is dependent on the Atg1-Atg13 complex (27). Therefore, we can monitor the anterograde movement of Atg9 through an epistasis analysis by introducing a second mutation in the atg1Δ background; if the second protein is required for Atg9 movement to the PAS, the cells display multiple Atg9 puncta. Atg9 was tagged with triple GFP at the C terminus (Atg9–3×GFP), which does not affect the normal localization and function of Atg9 (15, 28). We found that the additional deletion of KSP1 in the atg1Δ background did not affect Atg9 anterograde movement to the PAS (marked with RFP-Ape1), as we detected a single punctum corresponding to Atg9–3×GFP (Fig. 2D). Essentially 100% of the Atg9–3×GFP accumulated at the PAS and colocalized with RFP-Ape1, indicating that Ksp1 is not needed for the proper trafficking of the core autophagy component Atg9 during autophagosome/Cvt vesicle formation. In contrast, the deletion of ATG27, which is involved in Atg9 trafficking to the PAS (29), in the atg1Δ background resulted in the formation of multiple GFP-Atg9 puncta that did not colocalize with RFP-Ape1. Therefore, we propose that Ksp1 is likely to be involved in an earlier step, i.e. induction/regulation of nonspecific autophagy rather than autophagosome formation.

Ksp1 Negatively Regulates Autophagy through Activating the TORC1 Pathway

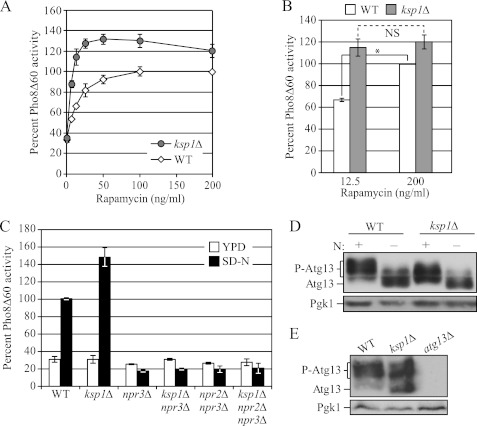

The induction of nonspecific autophagy is regulated largely through TOR complex 1. In growing conditions, TORC1 is highly activated to tightly suppress the induction of autophagy, whereas in nitrogen starvation conditions, the TORC1 activity is strongly suppressed to allow the induction of autophagy. We hypothesized that Ksp1 might negatively regulate the induction of nonspecific autophagy through the TORC1 pathway. To address this, we examined how the deletion of Ksp1 affected Pho8Δ60 activity when autophagy was inhibited with rapamycin, a small molecule that primarily inhibits TORC1. We hypothesized that if Ksp1 suppressed autophagy through TORC1 activation, ksp1Δ cells would not display a significant increase of autophagy when TORC1 was strongly inhibited with a high concentration of rapamycin, although there would be a more significant increase in autophagy when TORC1 was partially inhibited by a lower (subsaturating) concentration of rapamycin.

In the wild-type cells, Pho8Δ60 activity reached a maximum at 100 ng/ml rapamycin, and in the ksp1Δ cells, the activity was almost saturated at 25 ng/ml. The most significant difference in the Pho8Δ60 activity between the wild-type and ksp1Δ cells was observed at the lowest concentrations of rapamycin; the ksp1Δ cells showed an ∼60% increase in Pho8Δ60 activity relative to the wild type at 12.5 ng/ml, whereas there was only an ∼20% increase at 200 ng/ml (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that the increased autophagy seen in the ksp1Δ cells occurred, at least in part, through inhibition of the TORC1 pathway.

FIGURE 3.

Ksp1 activates TORC1 to suppress autophagy. A, comparison of the Pho8Δ60 activity of the ksp1Δ mutant (MUY16) with that of the wild type (ZFY202) after treatment with different concentrations of rapamycin. Cells expressing Pho8Δ60 were grown in YPD and treated with rapamycin (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 ng/ml) for 2 h. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells treated with 200 ng/ml rapamycin in growing medium, which was set to 100%. B, comparison of Pho8Δ60 activities between wild-type and ksp1Δ cells treated with a low (12.5 ng/ml) or high (200 mg/ml) concentration of rapamycin. Error bars indicate the S.D. of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; NS, difference was not significant (p > 0.05). C, comparison of the Pho8Δ60 activity of the ksp1Δ mutant with that of the wild type in npr3Δ and npr2Δ npr3Δ strains. Wild-type (ZFY202), ksp1Δ (MUY19), npr3Δ (MUY61), ksp1Δ npr3Δ (MUY62), npr2Δ npr3Δ (MUY63), and ksp1Δ npr2Δ npr3Δ (MUY64) cells were grown in YPD and treated with SD-N for 4 h. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells after starvation, which was set to 100%. Error bars indicate the S.D. of at least three independent experiments. D, Atg13 is less phosphorylated in the absence of Ksp1. Atg13 was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Atg13 antibody. Wild-type (ZFY202) and ksp1Δ (MUY19) cells harboring YEp351(ATG13) (a multicopy plasmid) were grown in YPD and starved in SD-N for 2 h. E, ksp1Δ cells have hypophosphorylated Atg13. The phosphorylation status of endogenous Atg13 was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Atg13 antibody. Wild-type (ZFY202), ksp1Δ (MUY19), and atg13Δ (MUY20) cells were grown in YPGal medium.

The regulatory mechanisms that modulate the activity of TORC1 are not completely known. However, a genome-wide screen recently identified Npr2 and Npr3 as negative regulators of TORC1 (30); in strains deleted for NPR2 and/or NPR3, TORC1 is hyperactive. Thus, as a corollary to the analysis with subsaturating doses of rapamycin (Fig. 3A), we decided to test whether deletion of KSP1 increased autophagy when TORC1 was hyperactivated by NPR2 or NPR3 deletion. In agreement with the published data, npr3Δ and npr2Δ npr3Δ strains showed a significant reduction of Pho8Δ60 activity (Fig. 3C). Further deletion of KSP1 did not result in an increase of Pho8Δ60 activity in the npr3Δ or npr2Δ npr3Δ strains. Taken together, these results consistently suggest that Ksp1 down-regulates autophagy through activating the TORC1 pathway.

To assess TORC1 activity directly, we looked at the phosphorylation status of Atg13, which is a substrate of TORC1 (4, 5). The dephosphorylation of Atg13 by inhibition of TORC1 correlates with the induction of autophagy. In wild-type cells, overexpressed Atg13 was highly phosphorylated in growing conditions; however, in ksp1Δ cells, there was a decrease in the extent of Atg13 hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 3D), and this was more evident when examining the endogenous Atg13 protein (Fig. 3E; note the increase in the more rapidly migrating band). The strongest difference in the phosphorylation status of Atg13 was seen when cells were grown in galactose as the carbon source. This finding is consistent with the Pho8Δ60 activity assays, as the ksp1Δ cells showed a stronger increase in autophagy activity when galactose was the sole carbon source (Fig. 4). After starvation, most of the Atg13 was dephosphorylated in the wild-type cells as well as in the ksp1Δ strain. These results suggested that the deletion of KSP1 increased autophagy by inhibiting TORC1 activity; in other words, Ksp1 may activate TORC1.

FIGURE 4.

Ksp1 suppresses autophagy in part via TORC1-dependent phosphorylation of Atg13 serine residues. The Pho8Δ60 activity and the immunoblotting of Atg13 were analyzed in cells harboring plasmids expressing either wild-type Atg13 (p416GAL1(Atg13-WT); WT) or the Atg13 mutant in which eight serine residues phosphorylated by TORC1 are mutated to alanine (p416GAL1(Atg13–8SA); 8SA). To express Atg13, which is under the control of the GAL1 promoter, wild-type (MUY20) and ksp1Δ (MUY40) cells were grown in YPD to A600 = 0.8 and shifted to YPGal for 4 h. The indicated cells were treated with rapamycin for 2 h before collection. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells treated with rapamycin, which was set to 100%. Error bars indicate the S.D. of at least three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; NS, difference was not significant (p > 0.05 for lanes 4 and 8, p > 0.25 for lanes 6 and 8).

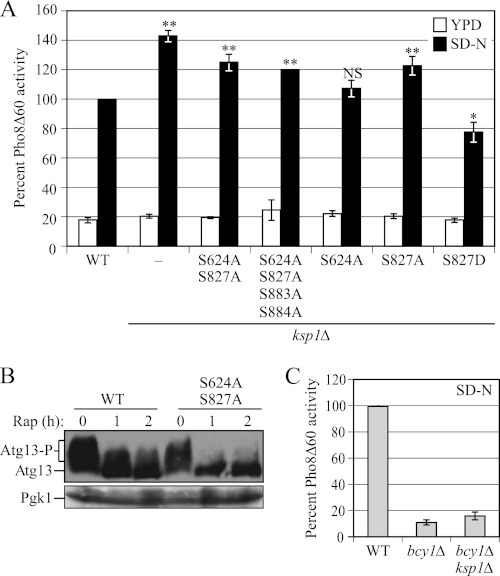

Considering the reduced TORC1 activity in the absence of Ksp1, we next asked whether Ksp1 negatively suppresses autophagy solely through the TORC1 pathway. Previously, the TORC1-dependent phosphorylation sites in Atg13 were identified (5). At least eight serine residues of Atg13 were phosphorylated in a TORC1-dependent manner, and cells expressing an Atg13(8SA) mutant, which replaces these eight serine residues with alanine, induce autophagy even in nutrient-rich conditions. Thus, we decided to examine whether the increased Pho8Δ60 activity seen in the ksp1Δ cells depended on the dephosphorylation of these TORC1-targeted serine residues in Atg13. We expressed the wild-type Atg13 and Atg13(8SA) mutant under the control of the GAL1 promoter, and we assessed the Pho8Δ60 activities and Atg13 migration patterns in the wild-type and ksp1Δ backgrounds (Fig. 4).

As mentioned above, the ksp1Δ strain showed a clear increase in Pho8Δ60 activity even in growing conditions when using galactose as the sole carbon source (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 5). In agreement with the previous study (5), wild-type cells expressing Atg13(8SA) showed substantially increased Pho8Δ60 activity compared with cells expressing wild-type Atg13 even prior to autophagy induction (Fig. 4, compare lanes 1 and 3). The ksp1Δ strain expressing wild-type Atg13 showed Pho8Δ60 activity that was elevated to a level similar to that seen with wild-type cells expressing Atg13(8SA) (Fig. 4, compare lanes 3 and 5), even though phosphorylation of Atg13 was much higher in the former. Furthermore, expression of the Atg13(8SA) mutant in the ksp1Δ background resulted in a further increase in activity beyond that seen in the ksp1Δ strain prior to autophagy induction (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 and 7). These findings suggest that the effect of Ksp1 in decreasing autophagy activity does not occur solely by enabling TORC1-dependent phosphorylation of Atg13. An additional caveat in this interpretation, however, is that TORC1 may phosphorylate residues on Atg13 in addition to the eight that have been identified, so that the combination of Atg13(8SA) along with the absence of Ksp1 may completely eliminate TORC1-dependent phosphorylation. Furthermore, TORC1 inhibits autophagy by mechanisms other than phosphorylation of Atg13, and these may also depend on Ksp1 function.

Nonetheless, the absence of Ksp1 did have an effect on Atg13 phosphorylation. In the wild-type background, cells treated with rapamycin still showed partial phosphorylation of Atg13 (Fig. 4, lane 2). In contrast, in the ksp1Δ background, phosphorylated Atg13 was not detected in the presence of rapamycin (Fig. 4, lane 6), in agreement with our finding that Ksp1 was required for efficient TORC1-dependent Atg13 phosphorylation (Fig. 3, D and E). Consistent with these observations, in wild-type cells treated with rapamycin, Atg13(8SA) expression resulted in an increase in Pho8Δ60 activity (Fig. 4, compare lanes 2 and 4); however, in the ksp1Δ background (i.e. where there was essentially no difference in Atg13 phosphorylation between wild-type Atg13 and Atg13(8SA)), expression of Atg13(8SA) had essentially no effect (Fig. 4, compare lanes 6 and 8).

Autophagy was more strongly induced with rapamycin than simply by expressing Atg13(8SA) without rapamycin (Fig. 4, compare lanes 2–4), suggesting that TORC1 may indeed inhibit autophagy not only via phosphorylation of the eight identified serine targets of Atg13. Similarly, in the wild-type background, the Pho8Δ60 activity of cells expressing Atg13(8SA) was further increased (∼2.8-fold after subtracting the background) by rapamycin treatment (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4). However, in the ksp1Δ background, cells expressing Atg13(8SA) showed a much smaller increase (∼1.6-fold) after rapamycin treatment (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 8). Together, these data suggest that TORC1 activity was further reduced in the ksp1Δ background. Finally, the observation that the Pho8Δ60 activity of cells expressing Atg13(8SA) in the presence of rapamycin was slightly but significantly increased in the ksp1Δ strain compared with the wild type (Fig. 4, compare lanes 4 and 8) suggested that Ksp1 may function through some other mechanism in addition to the activation of TORC1; however, we again note the caveat that the deletion of KSP1 may affect the TORC1-dependent phosphorylation of Atg13 on additional residues and/or other aspects of TORC1 inhibition of autophagy such as the phosphorylation of Atg1. Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that the increased Pho8Δ60 activity, and decreased phosphorylation of Atg13, seen in the absence of Ksp1 is also due to the activation of a phosphatase that is normally inhibited by Ksp1 in nutrient-rich conditions.

Ksp1 Is Activated by PKA

A recent study showed that Ksp1 is phosphorylated by PKA (31), another negative regulator of autophagy (8). Mass spectrometry analysis identified Ksp1 residues Ser-591, Ser-624, Ser-827, and Ser-884, which have a PKA consensus phosphorylation motif, as being authentic targets (31). Accordingly, we decided to assess the Pho8Δ60 activity of cells expressing Ksp1 mutated at those Ser residues to examine whether their phosphorylation status affected the ability of Ksp1 to suppress autophagy activity (Fig. 5A). All the phospho-mutants were genomically integrated under the control of the endogenous KSP1 promoter in the ksp1Δ background. Mutation of Ser-591 to alanine (S591A) resulted in reduced protein levels, suggesting that the protein was unstable, whereas the other mutations had no affect on stability (data not shown). We found that the mutation Ksp1S827A resulted in increased Pho8Δ60 activity (∼20%) in starvation conditions, which was approximately half the increase seen with the complete deletion of KSP1 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, only a marginal increase was seen with Ksp1S624A; a combination of both mutations resulted in a level of Pho8Δ60 activity similar to that seen with the S827A mutation alone, and no further increase occurred with mutation of Ser-883 and Ser-884 to alanine.

FIGURE 5.

Ksp1 is activated by PKA. A, comparison of the Pho8Δ60 activity of Ksp1 variants that contain a mutation(s) of a PKA phosphorylation site(s). Wild-type (ZFY202), ksp1Δ (MUY16), or ksp1Δ cells with integrated ksp1 mutations, KSP1-S624A,S827A (MUY24), KSP1-S624A,S827A,S883A,S884A (MUY25), KSP1-S624A (MUY28), KSP1-S827A (MUY23), and KSP1-S827D (MUY27) cells in a Pho8Δ60 strain background were grown in YPD and shifted to nitrogen starvation (SD-N) medium for 4 h. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells cultured in SD-N, which was set to 100%. Error bars indicate the S.D. of at least three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; NS, difference was not significant. B, Atg13 of wild-type (ZFY202) and KSP1-S624A,S827A (MUY24) cells harboring the multicopy YEp351(ATG13) plasmid were analyzed by immunoblotting. Cells were grown in YPD and shifted to YPGal at A600 = 0.8 for 4 h, then treated with rapamycin for the indicated times before the cells were collected, and processed for Western blot. C, Pho8Δ60 activities of wild-type (ZFY202), bcy1Δ (MUY29), and bcy1Δ ksp1Δ (MUY32) cells were determined. Cells were grown in YPD and starved (SD-N) for 6 h. The Pho8Δ60 activity was normalized to the activity of wild-type cells treated with SD-N, which was set to 100%. Error bars indicate the S.D. of at least three independent experiments.

Consistent with our data from the ksp1Δ mutant, the migration of Atg13 appeared to be faster in Ksp1S624A,S827A mutant cells than in wild-type cells in the presence of rapamycin (Fig. 5B), although there was no obvious difference in growing conditions. Finally, we generated a phosphomimetic mutant by changing Ser-827 to aspartic acid and found that the corresponding mutant, Ksp1S827D, exhibited a partial decrease (∼20%) of Pho8Δ60 activity (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that the phosphorylation of Ksp1 by PKA, especially on Ser-827, may activate Ksp1 to inhibit autophagy.

Several studies have suggested that PKA and TORC1 are connected to suppress autophagy. However, little is known about the mechanism of this connection or the relevant proteins involved. Our results suggested that Ksp1 is activated by PKA to inhibit autophagy in part through TORC1-dependent Atg13 phosphorylation. We extended this analysis by examining whether PKA inhibits autophagy mainly via Ksp1. PKA can be hyperactivated by deletion of BCY1, an inhibitory subunit of PKA (32), which results in a significant reduction of autophagy (14). Therefore, we assessed the Pho8Δ60 assay in bcy1Δ cells; as with our analysis of TORC1, we predicted that if PKA inhibits autophagy mainly via Ksp1, the deletion of KSP1 would largely suppress the reduced Pho8Δ60 activity phenotype seen in the bcy1Δ background. Consistent with our previous results (14), the Pho8Δ60 activity was significantly reduced in bcy1Δ cells in nitrogen starvation conditions (Fig. 5C). The deletion of KSP1, however, did not result in a substantial recovery of the Pho8Δ60 activity in the bcy1Δ background (Fig. 5C). This result suggested that PKA suppresses autophagy through additional mechanisms besides the activation of Ksp1.

DISCUSSION

TORC1 plays a central role in controlling many cellular events, such as protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and autophagy, by responding to the nutritional state of the cell. However, the mechanism of how the information about nutrient level is transmitted to TORC1 is far from being understood. In this study, we found that the uncharacterized Ser/Thr kinase Ksp1 has a negative regulatory role in autophagy. Our findings suggested that Ksp1 suppresses autophagy via (at least in part) the TORC1 pathway, leading to hyperphosphorylation of Atg13. Moreover, based on Pho8Δ60 activity assays, the deletion of KSP1 led to a substantial increase in autophagy in an otherwise wild-type strain under conditions of nitrogen starvation. In contrast, KSP1 deletion resulted in only a slight increase of autophagy under conditions in which TORC1 was already strongly inhibited by rapamycin. From these results, we propose that Ksp1 activates a negative regulatory component upstream of the TORC1 pathway, or at the level of TORC1 itself, to suppress autophagy, rather than affecting Atg13 phosphorylation downstream of TORC1. Hence, Ksp1 may play a role in sensing the nutritional status and transmitting the corresponding signal to TORC1 to integrate and properly regulate downstream metabolic pathways. Based on our results with the ksp1Δ strain, we predicted that overexpression of Ksp1 would act to inhibit autophagy under otherwise inducing conditions; however, we found that constitutive overexpression of this protein was lethal, whereas overexpression of the kinase-inactive mutant was tolerated. Furthermore, regulable overexpression of Ksp1 with the GAL1 promoter did not inhibit autophagy but rather caused an increase in activity. These results suggest that overexpression resulted in a dominant negative phenotype, possibly by interfering with the proper stoichiometry of a negative regulatory complex.

Although our data suggested that Ksp1 activates TORC1 to suppress autophagy, it is not clear whether this happens in a direct or indirect manner. Recently, a large scale analysis of the protein kinase interaction network revealed that Ksp1 physically interacts with TORC1 (33); Ksp1 was immunoprecipitated with Kog1, a homolog of mammalian RAPTOR and an essential component of MTORC1. Thus, Ksp1 may activate TORC1 through a direct physical interaction; however, there are as of yet no data indicating that TORC1 components are phosphorylated by Ksp1. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that Ksp1 also acts through a TORC1-independent pathway to suppress autophagy, because ksp1Δ cells still showed an increase in Pho8Δ60 activity even under conditions in which the TORC1 pathway was inhibited by rapamycin treatment, although this may reflect incomplete inhibition of TORC1 by rapamycin.

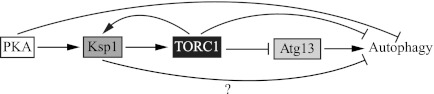

Ksp1 has several consensus sites for phosphorylation by PKA, and a recent study demonstrates that Ksp1 is indeed a PKA substrate (31). In this study, site-directed mutagenesis of the PKA-dependent phosphorylation sites suggested that the PKA phosphorylation of Ksp1, especially on Ser-827, may partially activate Ksp1 to suppress autophagy. Several studies have revealed that the Ras-PKA pathway down-regulates autophagy by coordinating with the TORC1 pathway. Our data suggest that Ksp1 might be responsible for connecting these two pathways to suppress autophagy; however, the Ras-PKA pathway also appears to be able to suppress autophagy via a Ksp1-TORC1-independent pathway. This finding is not surprising because other studies suggest that the Ras-PKA and TORC1 pathways coordinate with each other but also control signal transduction independently. For example, in addition to Atg1, PKA directly phosphorylates Atg13 on sites distinct from those targeted by TORC1, to regulate Atg13 localization to the PAS, suggesting that those two pathways control autophagy independently (9). In our model, TORC1 may be downstream of PKA-Ksp1 (Fig. 6); however, a mechanism of feedback regulation of Ksp1 by TORC1 might also exist, at least partially through PKA-independent phosphorylation because Ksp1 is phosphorylated in a TORC1-dependent manner (34). Thus, in the end, TORC1 may still play a primary role in the regulation of autophagy via orchestrating many of the signaling molecules that regulate this pathway, including Ksp1.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic model of the regulatory mechanism of Ksp1 in autophagy. Ksp1 may be positively regulated by PKA phosphorylation, and Ksp1 may, in turn, activate TORC1. The TORC1 activation by Ksp1 allows hyperphosphorylation of Atg13, resulting in down-regulation of autophagy. Ksp1 might have a TORC1-Atg13-independent mechanism that suppresses autophagy, and Ksp1 may be subject to feedback regulation by TORC1 (shown here as activating, but there are no data that address this point).

So far, the physiological function of Ksp1 is poorly understood, although it is required for filamentous growth (12). Pseudohyphal growth in yeast is proposed to be an alternative to autophagy to promote survival in a nitrogen-depleted environment. Consequently, it is not surprising that nutrient-sensitive kinases such as TORC1 and the Ras-PKA pathway are also key elements in PHG regulation (35, 36). It was suggested that autophagy may restrain PHG, because overexpression of some ATG genes leads to the inhibition of PHG (11). On the one hand, we found that the deletion of KSP1, which decreases PHG (12), resulted in increased autophagy. On the other hand, the fus3Δ strain, which displays a hyperfilamentous phenotype, decreased autophagy. These results suggest that impaired PHG leads to, or is coordinated with, stimulation of autophagy. One hypothesis is that a partial loss of TORC1 activity is required for the induction of PHG, whereas a complete abolition of TORC1 activity blocks this process (35). In agreement with this idea, Ksp1 may partially activate TORC1 to promote PHG and suppress autophagy. Taken together, we propose that Ksp1 may participate in the fine-tuning of TORC1 activity to regulate PHG and autophagy, responding as necessary to the existing nutrient levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yoshiaki Kamada (National Institute for Basic Biology) for providing plasmids and Kai Mao (University of Michigan) for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM53396 (to D. J. K.). This work was also supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Research Fellowships for Young Scientists Grant 214774 (to M. U.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- PHG

- pseudohyphal growth

- Cvt

- cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting

- PAS

- phagophore assembly site

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Meijer W. H., van der Klei I. J., Veenhuis M., Kiel J. A. K. W. (2007) ATG genes involved in nonselective autophagy are conserved from yeast to man, but the selective Cvt and pexophagy pathways also require organism-specific genes. Autophagy 3, 106–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunn W. A., Jr., Cregg J. M., Kiel J. A. K. W., van der Klei I. J., Oku M., Sakai Y., Sibirny A. A., Stasyk O. V., Veenhuis M. (2005) Pexophagy. The selective autophagy of peroxisomes. Autophagy 1, 75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang K., Klionsky D. J. (2011) Mitochondria removal by autophagy. Autophagy 7, 297–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kamada Y., Funakoshi T., Shintani T., Nagano K., Ohsumi M., Ohsumi Y. (2000) Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1507–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamada Y., Yoshino K., Kondo C., Kawamata T., Oshiro N., Yonezawa K., Ohsumi Y. (2010) Tor directly controls the Atg1 kinase complex to regulate autophagy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1049–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Noda T., Ohsumi Y. (1998) Tor, a phosphatidylinositol kinase homologue, controls autophagy in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3963–3966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yorimitsu T., He C., Wang K., Klionsky D. J. (2009) Tap42-associated protein phosphatase type 2A negatively regulates induction of autophagy. Autophagy 5, 616–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Budovskaya Y. V., Stephan J. S., Reggiori F., Klionsky D. J., Herman P. K. (2004) The Ras/cAMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway regulates an early step of the autophagy process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20663–20671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stephan J. S., Yeh Y. Y., Ramachandran V., Deminoff S. J., Herman P. K. (2009) The Tor and PKA signaling pathways independently target the Atg1/Atg13 protein kinase complex to control autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17049–17054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Binda M., Péli-Gulli M. P., Bonfils G., Panchaud N., Urban J., Sturgill T. W., Loewith R., De Virgilio C. (2009) The Vam6 GEF controls TORC1 by activating the EGO complex. Mol. Cell 35, 563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma J., Jin R., Jia X., Dobry C. J., Wang L., Reggiori F., Zhu J., Kumar A. (2007) An interrelationship between autophagy and filamentous growth in budding yeast. Genetics 177, 205–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bharucha N., Ma J., Dobry C. J., Lawson S. K., Yang Z., Kumar A. (2008) Analysis of the yeast kinome reveals a network of regulated protein localization during filamentous growth. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2708–2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shintani T., Klionsky D. J. (2004) Cargo proteins facilitate the formation of transport vesicles in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29889–29894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yorimitsu T., Zaman S., Broach J. R., Klionsky D. J. (2007) Protein kinase A and Sch9 cooperatively regulate induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 4180–4189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Monastyrska I., He C., Geng J., Hoppe A. D., Li Z., Klionsky D. J. (2008) Arp2 links autophagic machinery with the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1962–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shintani T., Huang W.-P., Stromhaug P. E., Klionsky D. J. (2002) Mechanism of cargo selection in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. Dev. Cell 3, 825–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noda T., Klionsky D. J. (2008) The quantitative Pho8Δ60 assay of nonspecific autophagy. Methods Enzymol. 451, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Noda T., Matsuura A., Wada Y., Ohsumi Y. (1995) Novel system for monitoring autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 210, 126–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheong H., Klionsky D. J. (2008) Biochemical methods to monitor autophagy-related processes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 451, 1–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Widmann C., Gibson S., Jarpe M. B., Johnson G. L. (1999) Mitogen-activated protein kinase. Conservation of a three-kinase module from yeast to human. Physiol. Rev. 79, 143–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klionsky D. J., Baehrecke E. H., Brumell J. H., Chu C. T., Codogno P., Cuervo A. M., Debnath J., Deretic V., Elazar Z., Eskelinen E.-L., Finkbeiner S., Fueyo-Margareto J., Gewirtz D., Jäättelä M., Kroemer G., Levine B., Melia T. J., Mizushima N., Rubinsztein D. C., Simonsen A., Thorburn A., Thumm M., Tooze S. A. (2011) A comprehensive glossary of autophagy-related molecules and processes (2nd ed.). Autophagy 7, 1273–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie Z., Klionsky D. J. (2007) Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1102–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baba M., Osumi M., Scott S. V., Klionsky D. J., Ohsumi Y. (1997) Two distinct pathways for targeting proteins from the cytoplasm to the vacuole/lysosome. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1687–1695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lynch-Day M. A., Klionsky D. J. (2010) The Cvt pathway as a model for selective autophagy. FEBS Lett. 584, 1359–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scott S. V., Nice D. C., III, Nau J. J., Weisman L. S., Kamada Y., Keizer-Gunnink I., Funakoshi T., Veenhuis M., Ohsumi Y., Klionsky D. J. (2000) Apg13p and Vac8p are part of a complex of phosphoproteins that are required for cytoplasm to vacuole targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25840–25849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mari M., Griffith J., Rieter E., Krishnappa L., Klionsky D. J., Reggiori F. (2010) An Atg9-containing compartment that functions in the early steps of autophagosome biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 190, 1005–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reggiori F., Tucker K. A., Stromhaug P. E., Klionsky D. J. (2004) The Atg1-Atg13 complex regulates Atg9 and Atg23 retrieval transport from the pre-autophagosomal structure. Dev. Cell 6, 79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He C., Baba M., Cao Y., Klionsky D. J. (2008) Self-interaction is critical for Atg9 transport and function at the phagophore assembly site during autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5506–5516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yen W.-L., Legakis J. E., Nair U., Klionsky D. J. (2007) Atg27 is required for autophagy-dependent cycling of Atg9. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 581–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Neklesa T. K., Davis R. W. (2009) A genome-wide screen for regulators of TORC1 in response to amino acid starvation reveals a conserved Npr2/3 complex. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soulard A., Cremonesi A., Moes S., Schütz F., Jenö P., Hall M. N. (2010) The rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase A toward some but not all substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3475–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toda T., Cameron S., Sass P., Zoller M., Scott J. D., McMullen B., Hurwitz M., Krebs E. G., Wigler M. (1987) Cloning and characterization of BCY1, a locus encoding a regulatory subunit of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 1371–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Breitkreutz A., Choi H., Sharom J. R., Boucher L., Neduva V., Larsen B., Lin Z. Y., Breitkreutz B. J., Stark C., Liu G., Ahn J., Dewar-Darch D., Reguly T., Tang X., Almeida R., Qin Z. S., Pawson T., Gingras A. C., Nesvizhskii A. I., Tyers M. (2010) A global protein kinase and phosphatase interaction network in yeast. Science 328, 1043–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huber A., Bodenmiller B., Uotila A., Stahl M., Wanka S., Gerrits B., Aebersold R., Loewith R. (2009) Characterization of the rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that Sch9 is a central coordinator of protein synthesis. Genes Dev. 23, 1929–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vinod P. K., Sengupta N., Bhat P. J., Venkatesh K. V. (2008) Integration of global signaling pathways, cAMP-PKA, MAPK, and TOR in the regulation of FLO11. PLoS One 3, e1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cutler N. S., Pan X., Heitman J., Cardenas M. E. (2001) The TOR signal transduction cascade controls cellular differentiation in response to nutrients. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 4103–4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robinson J. S., Klionsky D. J., Banta L. M., Emr S. D. (1988) Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 4936–4948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kanki T., Klionsky D. J. (2008) Mitophagy in yeast occurs through a selective mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32386–32393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wallis J. W., Chrebet G., Brodsky G., Rolfe M., Rothstein R. (1989) A hyper-recombination mutation in S. cerevisiae identifies a novel eukaryotic topoisomerase. Cell 58, 409–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kanki T., Wang K., Baba M., Bartholomew C. R., Lynch-Day M. A., Du Z., Geng J., Mao K., Yang Z., Yen W.-L., Klionsky D. J. (2009) A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in selective mitochondria autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4730–4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang Z., Geng J., Yen W.-L., Wang K., Klionsky D. J. (2010) Positive or negative roles of different cyclin-dependent kinase Pho85-cyclin complexes orchestrate induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 38, 250–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.