Abstract

Rare copy number variants (CNVs) play a prominent role in the etiology of schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders1. Substantial risk for schizophrenia is conferred by large (>500 kb) CNVs at several loci, including microdeletions at 1q21.1 2, 3q29 3, 15q13.3 2 and 22q11.2 4 and microduplication at 16p11.2 5. However, these CNVs collectively account for a small fraction (2-4%) of cases, and the relevant genes and neurobiological mechanisms are not well understood. Here we performed a large two-stage genome-wide scan of rare CNVs and report the significant association of copy number gains at chromosome 7q36.3 with schizophrenia (P= 4.0×10-5, OR = 16.14 [3.06, ∞]). Microduplications with variable breakpoints occurred within a 362 kb region and were detected in 29 of 8,290 (0.35%) patients versus two of 7,431 (0.03%) controls in the combined sample (p-value= 5.7×10-7, odds ratio (OR) = 14.1 [3.5, 123.9]). All duplications overlapped or were located within 89 kb upstream of the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor VIPR2. VIPR2 transcription and cyclic-AMP signaling were significantly increased in cultured lymphocytes from patients with microduplications of 7q36.3. These findings implicate altered VIP signaling in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia and suggest VIPR2 as a potential target for the development of novel antipsychotic drugs.

A majority of the rare CNVs that have been implicated in schizophrenia involve large (> 500 Kb) genomic regions where local segmental duplication architecture promotes frequent and nearly identical rearrangements by non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR). Because of the high structural mutation rates at these loci, the strong phenotypic effects of the causal variants, and the excellent power of most array platforms to detect such large CNVs, these genomic hotspots were the first to be detected in studies of CNVs in schizophrenia. Since most of the genome lacks the duplication architecture of the NAHR hotspots described above and because a variety of mutational mechanisms can give rise to structural rearrangements, causal variants in other regions of the genome may consist of CNVs that are individually more rare and smaller (< 500 kb) than those arising at NAHR hotspots. For example, microdeletions of the gene Neurexin-1 (NRXN1), which are highly enriched in autism and schizophrenia 6,7, consist of overlapping deletions with non-recurrent breakpoints. NRXN1 deletions are not flanked by segmental duplications, and may occur by different mutational mechanisms such as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or DNA replication-mediated rearrangement.

In order to identify novel schizophrenia genes, we investigated copy number variation genome-wide using an approach that detects enrichment of multiple overlapping rare variants. Regions of interest were defined in a primary sample of 802 patients and 742 controls as genomic segments containing CNVs in at least two cases and in no controls. This discovery step yielded 114 genomic regions of interest. In the secondary cohort of 7,488 patients and 6,689 controls, we assessed the association of these regions with schizophrenia (Supplementary Table 2). All CNVs overlapping each of the 114 regions of interest were collected, and CNV breakpoints falling within each region were used to partition the region into a series of non-overlapping segments or bins (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Significance was tested within each bin by the exact conditional test, with ethnicity and study as covariates. The segment with the minimal p-value was defined as the peak of association within the region, and a permutation-based multiple testing correction scheme was applied in order to obtain the p-value for the region.

Of the 114 regions detected in the first step, four had statistically significant associations in the secondary sample after Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/114 = 4.4×10-4). Table 1 lists the four regions with significant p-values meeting this criterion and an additional four loci with nominally significant p-values (P < 0.05) in the secondary cohort. Regions with significant associations were loss of copy number at 22q11.2 (P < 5×10-6, OR = 14.2), gain at 7q36.3 (P = 4.0×10-5, OR = 16.4), gain at 16p11.2 (P = 1.0×10-4, OR = 16.1) and loss at 15q13.3 (P = 1.6×10-4, OR = 14.9). No significant heterogeneity was observed for these genomic regions across studies (Breslow-Day-Tarone P = 0.42 – 0.83).

Table 1. Significant association of four CNV regions with schizophrenia.

Events, odds ratios, and exact conditional (EC) P-values listed here correspond to the peak of association. Empirical P-values for the entire target region were then computed based on permutation of case and control labels. The minimal threshold for statistical significance after Bonferroni correction for the 114 loci tested was empirical P<4.4×10-4.

| Primary | Secondary | Peak | Peak | Perm. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region (hg18) | Genes | Band | Type | Cases | Ctrls | Cases | Ctrls | OR | P-value | P-value |

| chr22:19,786,712-19,795,854 | BCR | 22q11.2 | del | 2 | 0 | 22 | 0 | *14.21 [4.24, Inf] | 2.4×10-6 | <5.00×10-6 |

| chr7:158,731,401-158,810,016 | VIPR2** | 7q36.3 | dup | 2 | 0 | 18 | 1 | 16.41 [3.11, Inf] | 8.39×10-5 | 4.00×10-5 |

| chr16:29,569,647-30,209,382 | 28 genes | 16p11.2 | dup | 4 | 0 | 18 | 1 | 16.14 [3.06, Inf] | 0.000097 | 0.0001 |

| chr15:29,694,064-29,705,665 | OTUD7A | 15q13.3 | del | 2 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 14.94 [2.80, Inf] | 0.00023 | 0.00016 |

| chr7:158,448,321-158,605,936 | VIPR2, BC042556 | 7q36.3 | dup | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 | *8.26 [2.36, Inf] | 0.00086 | 0.0007 |

| chr15:28,881,608-28,991,107 | MTMR15 | 15q13.3 | del | 2 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 14.94 [2.80, Inf] | 0.00023 | 0.001 |

| chr3:196,826,549-196,872,080 | CR597873, SDHALP2 | 3q29 | dup | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | * 5.65 [1.56, Inf] | 0.01 | 0.005 |

| chr6:162,835,583-162,997,592 | PARK2 | 6q26 | dup | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | * 4.41 [1.17, Inf] | 0.03 | 0.044 |

When the number of controls in the secondary sample was 0, Haldane correction (adding 0.5 to each cell of table) was applied in order to get a finite OR.

All genes overlapping with the target region are listed or the closest gene within 100 kb.

15q13.3, 16p11.2 and 22q11.2 are well-documented loci conferring increased risk for schizophrenia 2,5,8. All are hotspots for non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR), and all alleles contributing to the association consist of large deletions with similar breakpoints. By contrast, microduplications at 7q36.3 have not been previously implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders. The 7q36.3 region harbored CNVs that overlapped but differed in size and breakpoint positions (Fig. 1a). The peak of association is located in the subtelomeric region of 7q, upstream of the gene VIPR2. Also, ranking fifth among the associations genome-wide was another region, 125 kb proximal to the peak at 7q36.3 (P = 0.0007, Table 1). Combining the two 7q36.3 regions into a single 362 kb region (chr7:158,448,321-158,810,016), duplications were detected in 29 of 8,290 (0.35%) patients and 2 of 7,431 (0.03%) controls in this study. The p-value for the combined region in the combined sample was 5.7×10-7 and the OR was 14.1 [3.5, 123.9]. A complete list of 7q36.3 CNVs is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

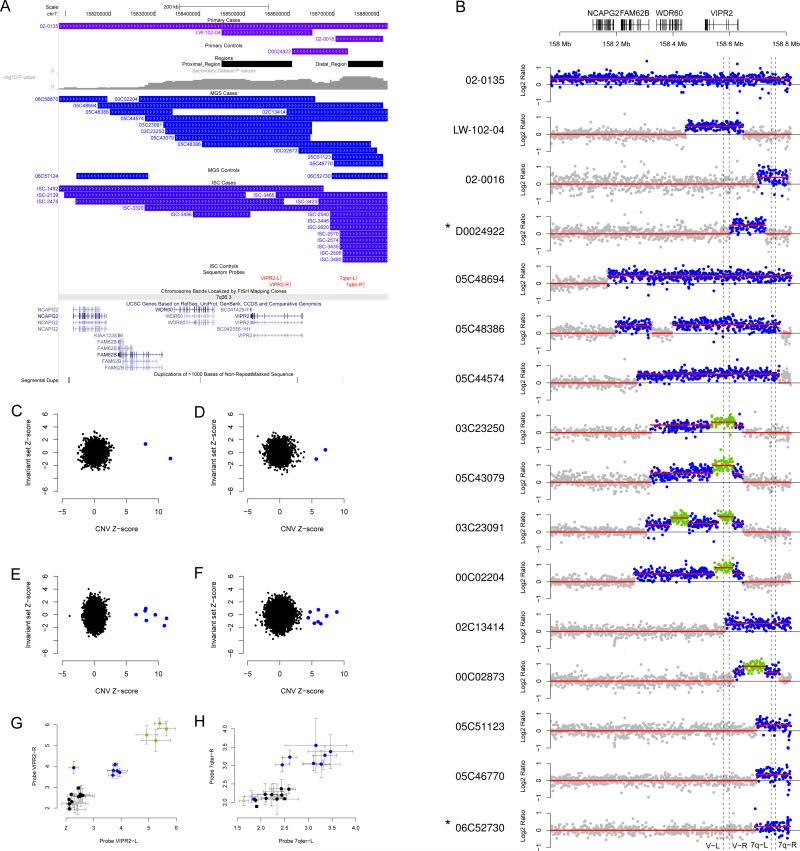

Figure 1. Detection and validation of microduplications and triplications of 7q36.3.

a) Map of CNVs detected in the primary and secondary cohorts from the UCSC genome browser. (b) Plots of probe intensity ratios for 16 CNVs detected in the primary and MGS datasets. All are cases, with the exception of two controls, who are indicated with an asterisk*. Regions with estimated copy numbers of 2, 3 and 4 are highlighted in gray, blue and green, respectively. Locations of four Sequenom validation assays are shown (dashed lines). (c-f) CNV genotypes were confirmed by MeZOD cluster plots of probe intensity ratios of the proximal and distal regions and in the primary dataset (c and d, respectively) and secondary dataset (e and f, respectively). Absolute copy numbers were confirmed for duplications and triplications of the proximal (g) and distal (h) regions by Sequenom MASSarray genotyping.

We examined sensitivity and specificity of CNV calls in the 7q36 region to determine the possibility of a spurious association (Supplementary Note). No additional duplications >100 kb were detected after reducing the stringency of our CNV filtering criteria. Second, identical CNV calls were obtained using a more sensitive targeted CNV calling algorithm, median Z-score Outlier Detection (MeZOD)5, (Fig. 1c-f). All but one of the duplications (control sample 06C52730) were confirmed using the Sequenom MASSarray genotyping platform with assays designed for the proximal region (Fig. 1g) and for the distal region (Fig. 1h).Validated CNVs discovered in the MGS subjects were mapped at higher resolution using the NimbleGen HD2 platform, and plots of probe intensity ratios from the HD2 array are shown in Figure 1b and Supplementary Figure 3. In addition, tandem duplications of the VIPR2 gene were confirmed in two patients by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Supplementary Figure 4).

Unexpectedly, manual examination of probe ratios in Figure 1b revealed additional structural complexity within some of the 7q36.3 CNVs. Copy number profiles in four patients (03C23250, 05C43079, 03C23091 and 00C02204) suggested triplications nested within duplications of the proximal region (Fig. 1b). In all four patients, a triplication overlapped with exons 3 and 4 of the gene VIPR2. A copy number of four was confirmed in these samples using the Sequenome MASSarray CNV assay (Fig. 1g), and results for all samples were consistent with results in Figure 1b. VIPR2 transcripts were amplified from mRNA samples from the four triplication carriers. The normal VIPR2 transcript was detected in all samples, and we did not observe a larger product corresponding to a transcript with duplicated exons.

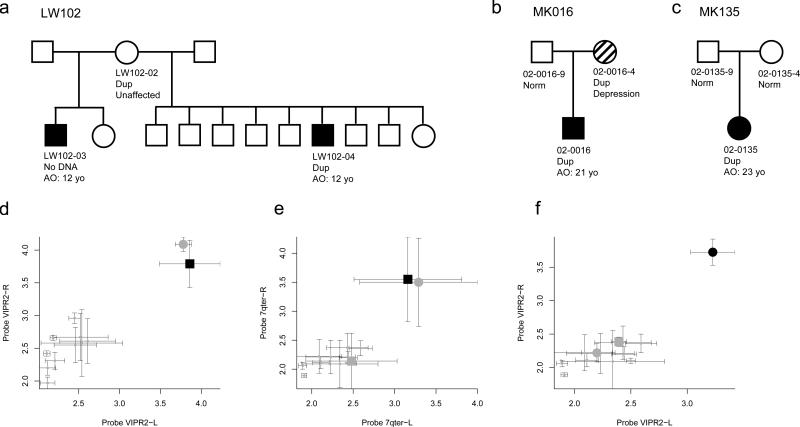

Inheritance of the duplication at 7q36.3 could be evaluated in three families (Fig. 2). In family 02-135, the duplication was confirmed in the proband, but not detected in either of the unaffected parents, and thus is apparently de novo (Fig. 2f). In family 02-016, the duplication was detected in the proband and in a mother with a diagnosis of depression (Fig. 2d). In family LW102, the duplication was detected in the proband and in an unaffected mother. The proband's mother also had a son with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (LW-102-03) from a second marriage, but DNA was not available on this individual. Clinical psychiatric reports of patients 02-016 and 02-135 are provided in the Supplementary Note.

Figure 2. Patterns of CNV inheritance in families.

Pedigree diagrams are shown for families (a) LW102, (b) 02-016 and (c) 02-135, along with the Sequenom validation for families (d) LW102, (e) 02-016 and (f) 02-135. Sequenom validation was performed on (a) mother and one of the affected sons, and (b) all three family members, along with 10 CEU HapMap controls. Sequenom assays confirmed that duplications were present in the patients and maternally inherited from LW102-2 and 02-0016-4.

Variable expressivity is often characteristic of pathogenic CNVs 5. We evaluated the spectrum of psychiatric phenotypes associated with 7q36.3 duplications by screening for these events in individuals with bipolar disorder or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Microarray data were available for 2,777 patients from the Bipolar Genome Study (BiGS), for 996 ASD patients from the Autism Genome Project Consortium (AGP), and from our unpublished analyses of 114 patients with ASD using the NimbleGen HD2 platform. Microduplications of 7q36.3 (>100 kb in size) were detected in three of 1,110 (0.27%) of patients with ASD; compared with the controls described above, P=0.018. Microduplications at 7q36.3 were detected in two of 2,777 (0.07%) patients with bipolar disorder; compared with the controls, P = 0.23. These results provide preliminary evidence that the clinical phenotypes associated with 7q36.3 duplications may include pediatric neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, but do not include bipolar disorder. Also worthy of note, larger chromosomal abnormalities involving 7q have been reported in association with neurodevelopmental disorders, including deletions of 7q36-7qter 9,10 and duplications of 7q35-7qter 11; a 550 kb duplication of 7qter (of unknown clinical relevance) has been reported in a patient with neurofibromatosis 12.

These genetic data implicate the gene VIPR2. All variants contributing to the observed association at 7q36.3 overlap with this gene or lie within the gene-less subtelomeric region <89 kb from the transcriptional start site of VIPR2. VIPR2 encodes the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) receptor VPAC2, a G protein-coupled receptor that is expressed in a variety of tissues including, in the brain, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus 13. VPAC2 binds VIP 14, activates cyclic-AMP signaling and PKA, regulates synaptic transmission in the hippocampus 15,16, and promotes the proliferation of neural progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus 17. Genetic studies in mouse have established that VIP signaling plays a role in learning and memory18. VPAC2 also plays a role in sustaining normal circadian oscillations in the SCN 19, and VIPR2-null 20 and VIPR2-overexpression 21 mice exhibit abnormal rhythms of rest and activity.

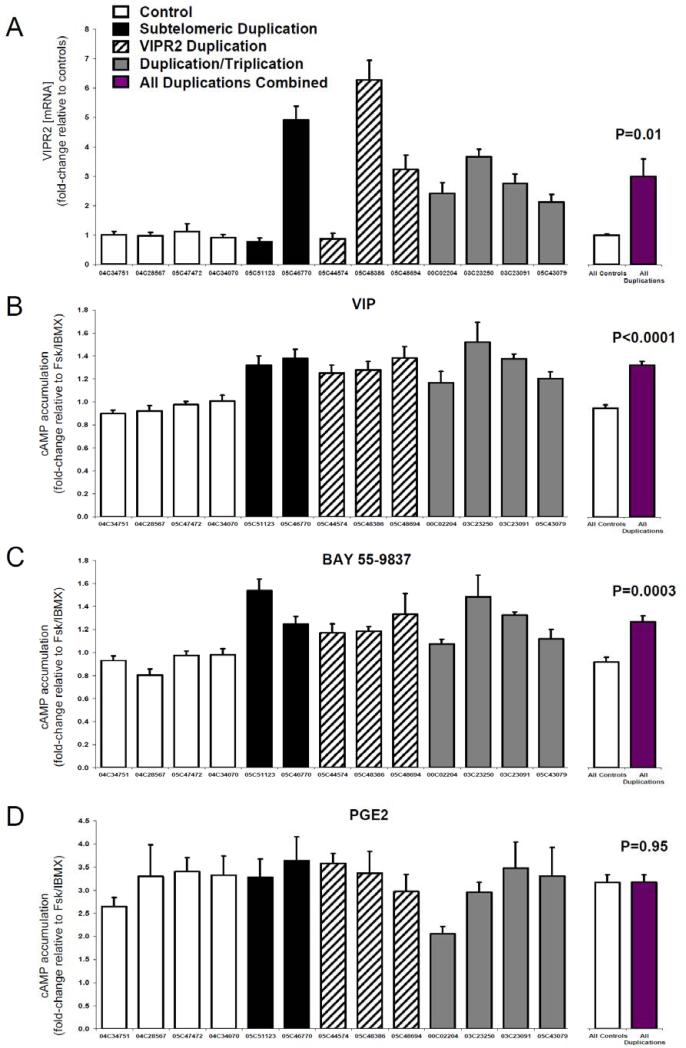

Cyclic-AMP signaling has been implicated in schizophrenia 22,23. We hypothesized that increases in VIPR2 transcription and VPAC2-mediated cAMP signaling would be a consequence of the microduplications at 7q36.3. We thus assessed VIPR2 mRNA and cAMP accumulation in response to VIP and a VPAC2-selective agonist (BAY 55-9837) in lymphoblastoid cell lines from eight MGS study subjects: two with subtelomeric duplications, three with duplications of VIPR2, four with partial triplications, and four controls with normal copy number of the region (see Supplementary Note). VIPR2 transcripts were present at low but measurable levels in all cell lines. VIPR2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in duplication carriers compared with controls (Fig. 3a). Likewise, cAMP responses to VIP and BAY 55-9837 were significantly greater in lymphoblastoid lines from carriers as compared to controls (Fig. 3b). In contrast, we observed no group difference in cAMP accumulation in response to a different GPCR agonist, prostaglandin E2, thus confirming that the effect of 7q36 duplications on cAMP accumulation is mediated by VPAC2R.

Figure 3. Duplications and triplications of 7q36.3 result in increased VIPR2 transcription and cyclic-AMP signaling.

(a) Quantitative PCR results of VIPR2 mRNA from lymphoblastoid cell lines. Two to four subjects were tested for each of four genotypes (subtelomeric duplication, VIPR2 duplication, exon 3/4 triplication, and normal diploid copy number as control). Results are expressed as the mean fold-change of CNV carriers relative to the mean of control samples. (b-c) Cyclic AMP accumulation was measured in the same cell lines in response to VIP (100nM) and the VPAC2 agonist BAY 55-9837 (100nM). Results are expressed as fold-change over forskolin/IBMX alone. (d) No significant differences were observed in cAMP response to another GPCR agonist, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, 1 μM), demonstrating that the effects are specific to VPAC2. For subjects, error bars represent standard error of the mean computed across replicates. Differences between the groups of 9 duplication carriers and 4 controls were tested using unpaired two sample t-tests.

The expression patterns that we observe suggest that a variety of different genomic duplications can influence the transcription of VIPR2. The exact genetic mechanism for this is unclear. Given that some risk variants are upstream of the gene and others are complex rearrangements that could potentially disrupt the duplicate copy, our results cannot be explained simply by an increase in gene dosage. It is likely that duplications of 7q36 impact the regulation of VIPR2. Tandem duplication of regulatory sequences, for instance, could affect expression of the gene. Alternatively, the subtelomeric location of VIPR2 could be relevant to the mechanism. Intrinsic regulation of telomere structure and function often impacts the transcriptional regulation of adjacent genes, a phenomenon known as telomere position effect (TPE) 24,25. If VIPR2 is under such epigenetic regulation, any large tandem duplication of the subtelomeric region could potentially cause the gene to escape repression. However, further studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which structural variants influence VIPR2 expression.

In light of the emerging roles of VIPR2 in the brain, our results support the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, in some patients, involves the dysregulation of cellular processes such as adult neurogenesis and synaptic transmission and of the corresponding cognitive processes of learning and memory. Furthermore, in light of the brain expression patterns of VIPR213, our results support the involvement of certain brain regions, such as hippocampus, amygdala and suprachiasmatic nucleus. The link between VIPR2 duplications and schizophrenia may have significant implications for the development of molecular diagnostics and treatments for this disorder. Genetic testing for duplications of the 7q36 region could enable the early detection of a subtype of patients characterized by overexpression of VIPR2. Significant potential also exists for the development of therapeutics targeting this receptor. For instance, a selective antagonist of VPAC2R could have therapeutic potential in patients who carry duplications of the VIPR2 region. Peptide derivatives 26 and small molecules 27 have been identified that are selective VPAC2 inhibitors, and these pharmacological studies offer potential leads in the development of new drugs. While duplications of VIPR2 account for a small percentage of patients, the rapidly growing list of rare CNVs that are implicated in schizophrenia suggests that this psychiatric disorder is, in part, a constellation of multiple rare diseases 1. This knowledge, along with a growing interest in the development of drugs targeting rare disorders 28, provides an avenue for the development of new treatments for schizophrenia.

METHODS SUMMARY

Cohort description

Our primary cohort consisted of unrelated patients derived from family-based studies conducted by investigators at the University of Washington, McLean Hospital, Columbia University, Trinity College Dublin, NYU and Harvard Medical Schools (Supplementary Table 1). All samples were analyzed by array CGH using the NimbleGen HD2 platform. The secondary cohort consisted of Affymetrix SNP Array 6.0 data from the MGS study of schizophrenia 29, publicly available data from the International Schizophrenia Consortium (ISC), genotyped using Affymetrix 6.0 and 5.0 platforms 2, and Affymetrix 6.0 data on an independent set of controls from the Bipolar Genome Study (BiGS) 30 (Supplementary Table 1).

Intensity data processing and rare CNV calling

With the exception of the published CNV calls from the ISC, all data were processed and analyzed centrally as follows. Microarray intensity data were normalized, and CNV calls were generated using an analysis package that we developed called C-score. All CNV call sets were filtered in a consistent fashion. In order to minimize the differential sensitivity of the various array platforms to detect CNVs, we limited our analysis to CNVs > 100 kb. This size range is readily detectable by all platforms used in this study. The same criteria have been previously applied to filter CNVs across studies 2. Last, sensitivity to detect large (>100 kb) copy number polymorphisms (CNPs) was evaluated at several locations in the genome. Overall sensitivity to detect CNVs was comparable in cases and controls in both cohorts. Additional details regarding C-score, statistical methods and evaluation of CNV call sets are described in the Supplementary Note.

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper and in the Supplementary Note.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a gift from Ted and Vada Stanley to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a gift to J.S. from the Beyster family foundation, NIH grants to J.S. (MH076431, HG04222), D.L.L. (MH071523), M.C.K (MH083989), P.I. (GM66232), F.M. (HL091061), D.K.W. (MH082945), M.K. (MH061399), L.E.D (MH044245), grants to J.S., D.K.W., D.L.L. and M.C.K from NARSAD,.grants to A.C., M.G., D.M. from the Wellcome Trust (072894/Z/03/Z) and Science Foundation Ireland (08INIB1916), a career development award to D.K.W. by the Veterans Administration, and grants to D.L.L. from the Sidney R,. Baer, Jr. Foundation and Essel Foundation . We wish to thank the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN), Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia (MGS) and the Bipolar Genome Study (BiGS) for providing data for this study (investigators listed in the Supplementary Note). We wish to thank Barbara Trask, Robert Malinow, and Joseph Gleeson for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions V.V and J.S. wrote the manuscript. V.V., S.M., D.M., H.H., F.M., V.M., S.Y., S.M.L., P.A.I. and J.S. designed the analytical strategy and analyzed the data. M.G., A.C., J.M., M.K., D.L.L., V.L-W., and L.E.D oversaw the recruitment and clinical assessment of study participants. M.D.A. performed cytogenetic analysis. A.B., A.P., and D.M. designed genotype assays and performed genotyping. H.H. and R.C. performed mRNA studies, F.M. performed biochemical studies. O.K., V.K., D.W.M, V.L-W, L.E.D., and M.K. contributed to the interpretation of clinical patient data. J.M., M.C.K, M.K., D.L.L., L.E.D., D.C., J.R.K, and E.S.G. contributed to the interpretation of data from genetic studies. P.A.I., L.M.I., and D.K.W contributed to the interpretation of data from functional studies. J.S. coordinated the study.

Competing interests statement The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Sebat J, Levy DL, McCarthy SE. Rare structural variants in schizophrenia: one disorder, multiple mutations; one mutation, multiple disorders. Trends Genet. 2009;25:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Schizophrenia Consortium Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulle JG, et al. Microdeletions of 3q29 confer high risk for schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karayiorgou M, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility associated with interstitial deletions of chromosome 22q11. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7612–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy SE, et al. Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/ng.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szatmari P, et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2007;39:319–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rujescu D, et al. Disruption of the neurexin 1 gene is associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefansson H, et al. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyson C, et al. Submicroscopic deletions and duplications in individuals with intellectual disability detected by array-CGH. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;139:173–185. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, et al. Submicroscopic subtelomeric aberrations in Chinese patients with unexplained developmental delay/mental retardation. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morava E, et al. Small inherited terminal duplication of 7q with hydrocephalus, cleft palate, joint contractures, and severe hypotonia. Clin Dysmorphol. 2003;12:123–127. doi: 10.1097/01.mcd.0000059768.40218.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartsch O, et al. Two independent chromosomal rearrangements, a very small (550 kb) duplication of the 7q subtelomeric region and an atypical 17q11.2 (NF1) microdeletion, in a girl with neurofibromatosis. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;119:158–164. doi: 10.1159/000109634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheward WJ, Lutz EM, Harmar AJ. The distribution of vasoactive intestinal peptide2 receptor messenger RNA in the rat brain and pituitary gland as assessed by in situ hybridization. Neuroscience. 1995;67:409–418. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00048-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fahrenkrug J. Transmitter role of vasoactive intestinal peptide. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;72:354–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang K, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide acts via multiple signal pathways to regulate hippocampal NMDA receptors and synaptic transmission. Hippocampus. 2009;19:779–789. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waschek JA. Vasoactive intestinal peptide: an important trophic factor and developmental regulator? Dev Neurosci. 1995;17:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000111268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaben M, et al. The neurotransmitter VIP expands the pool of symmetrically dividing postnatal dentate gyrus precursors via VPAC2 receptors or directs them toward a neuronal fate via VPAC1 receptors. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2539–2551. doi: 10.1002/stem.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaudhury D, Loh DH, Dragich JM, Hagopian A, Colwell CS. Select cognitive deficits in vasoactive intestinal peptide deficient mice. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown TM, Colwell CS, Waschek JA, Piggins HD. Disrupted neuronal activity rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-deficient mice. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2553–2558. doi: 10.1152/jn.01206.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harmar AJ, et al. The VPAC(2) receptor is essential for circadian function in the mouse suprachiasmatic nuclei. Cell. 2002;109:497–508. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Underhill PA, et al. Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations. Nat Genet. 2000;26:358–361. doi: 10.1038/81685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millar JK, et al. DISC1 and PDE4B are interacting genetic factors in schizophrenia that regulate cAMP signaling. Science. 2005;310:1187–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1112915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turetsky BI, Moberg PJ. An odor-specific threshold deficit implicates abnormal intracellular cyclic AMP signaling in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:226–233. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottschling DE, Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Zakian VA. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of Pol II transcription. Cell. 1990;63:751–762. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koering CE, et al. Human telomeric position effect is determined by chromosomal context and telomeric chromatin integrity. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1055–1061. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno D, et al. Development of selective agonists and antagonists for the human vasoactive intestinal polypeptide VPAC(2) receptor. Peptides. 2000;21:1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu A, Caldwell JS, Chen YA. Identification and characterization of a small molecule antagonist of human VPAC(2) receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;77:95–101. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun MM, Farag-El-Massah S, Xu K, Cote TR. Emergence of orphan drugs in the United States: a quantitative assessment of the first 25 years. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nrd3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi J, et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:753–757. doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang D, et al. Singleton deletions throughout the genome increase risk of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.