Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease, diagnosed by urinary albumin excretion rate (AER), is a critical symptom of chronic vascular injury in diabetes, and is associated with dyslipidemia and increased mortality. We investigated serum lipids in 326 subjects with type 1 diabetes: 56% of patients had normal AER, 17% had microalbuminuria (20 ≤ AER < 200 μg/min or 30 ≤ AER < 300 mg/24 h) and 26% had overt kidney disease (macroalbuminuria AER ≥ 200 μg/min or AER ≥ 300 mg/24 h). Lipoprotein subclass lipids and low-molecular-weight metabolites were quantified from native serum, and individual lipid species from the lipid extract of the native sample, using a proton NMR metabonomics platform. Sphingomyelin (odds ratio 2.53, P < 10−7), large VLDL cholesterol (odds ratio 2.36, P < 10−10), total triglycerides (odds ratio 1.88, P < 10−6), omega-9 and saturated fatty acids (odds ratio 1.82, P < 10−5), glucose disposal rate (odds ratio 0.44, P < 10−9), large HDL cholesterol (odds ratio 0.39, P < 10−9) and glomerular filtration rate (odds ratio 0.19, P < 10−10) were associated with kidney disease. No associations were found for polyunsaturated fatty acids or phospholipids. Sphingomyelin was a significant regressor of urinary albumin (P < 0.0001) in multivariate analysis with kidney function, glycemic control, body mass, blood pressure, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol. Kidney injury, sphingolipids and excess fatty acids have been linked in animal models—our exploratory approach provides independent support for this relationship in human patients with diabetes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11306-011-0343-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, NMR metabonomics, Fatty acids, Sphingolipids, Phospholipids, Lipoprotein subclasses

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes follows the autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta-cells at a young age. Acute symptoms can be controlled by insulin injections, but the diabetes-related disease burden increases with time due to chronic complications (Lithovius et al. 2011). An estimated third of patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes are affected by kidney disease, which is characterized by increased urinary albumin excretion, high blood pressure and a gradual decline in glomerular filtration (Gross et al. 2005; Mäkinen et al. 2008a). For individual prognosis, kidney disease is the crucial feature: it is associated with a ten-fold increase in mortality, often from cardiovascular disease or stroke before end-stage renal disease is reached (Forsblom et al. 2011; Groop et al. 2009; Morrish et al. 2001; Stadler et al. 2006).

Obesity, selective insulin resistance and lipotoxicity are recognized as important aspects of end-organ damage in diabetes (Groop et al. 2005). Adipose tissue in a state of over-nutrition can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory agents (Kennedy et al. 2009; Surmi and Hasty 2010), which could explain some of the observed chronic inflammation in atherosclerosis and diabetic kidney disease (Best et al. 2005; Cao et al. 2007; Saraheimo et al. 2003). Furthermore, a large proportion of type 1 diabetic patients satisfy the metabolic syndrome definition and particularly the dyslipidemia component of the definition increases the likelihood of complications and premature death (Mäkinen et al. 2008a; Thorn et al. 2005; Tolonen et al. 2009). Accordingly, the triglyceride-rich VLDL and cholesterol-carrying HDL subclasses are important covariates of diabetic complications (Jenkins et al. 2003; Soedamah-Muthu et al. 2003).

Various and partly conflicting differences in serum lipid species have been detected in high-risk children and type 1 diabetic patients (Fievet et al. 1990; Jain et al. 2000; Oresic et al. 2008; Seigneur et al. 1994). Serum phospholipids have been studied as structural components of lipoproteins, but their relevance for type 1 diabetes complications is not fully known (Bagdade and Subbaiah 1989; Watala and Józwiak 1990); sphingolipids have been associated with numerous diseases (Boini et al. 2010; Fox et al. 2011; Hicks et al. 2009; Piperi et al. 2004; Summers 2010), but their significance for human diabetic kidney disease needs clarification. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids are considered beneficial (Lee et al. 2010; Mori et al. 1989) whereas saturated fatty acids are likely to be harmful also in type 1 diabetes. However, information on serum lipid concentrations in type 1 diabetic subjects remains fragmented.

Metabonomics has the potential to recognize previously unconsidered associations between metabolic products and clinical end-points (Ala-Korpela 2007; Mäkinen et al. 2006). In this study, we investigate a number of lipids and other biochemical measures in a set of human subjects with long-standing type 1 diabetes with and without complications. Our aim is to find those biochemical quantities that are associated with the (i) diagnostic classification and (ii) continuous markers of kidney injury. The findings provide clues on the lipid mediators of vascular damage and biomarker candidates for further mechanistic and epidemiological studies.

Methods

We studied 326 type 1 diabetic patients (218 men and 108 women) as part of the Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy Study (Mäkinen et al. 2008a). The data collection was cross-sectional (serum and urine samples), but with longitudinal records of albuminuria and clinical history. Type 1 diabetes mellitus was defined as an age of onset below 35 years and initiation of insulin treatment within a year of onset.

The clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The normal range of urinary albumin excretion rate (AER) was defined as AER < 20 μg/min for night urine or AER < 30 mg/24 h for a timed circadian collection. Overt kidney disease was diagnosed if AER ≥ 200 μg/min or AER ≥ 300 mg/24 h (macroalbuminuria). The intermediary range (microalbuminuria, 20 ≤ AER < 200 μg/min or 30 ≤ AER < 300 mg/24 h) represents a clinically challenging borderline with no clear consensus on pathology. In this study, microalbuminuria was regarded as not having kidney disease, since we could not see reduced kidney function. AER exhibits a large daily variance and the kidney diagnosis was based on at least two out of three consecutive albumin tests. We also measured urinary albumin centrally from a single 24 h collection to obtain a continuous renal status (denoted by 24 h-AER). Laser treatment of the retina was used as an indicator of proliferative retinopathy.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical characteristics

| No kidney disease | Diabetic kidney disease | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 240 | 86 | – |

| Normal AER* | 76% | 0% | – |

| Microalbuminuria* | 24% | 0% | – |

| Macroalbuminuria* | 0% | 100% | – |

| Age (years) | 34 (18–60) | 42 (24–58) | 1.3 × 10−6 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 16 (2–47) | 29 (16–43) | 3.8 × 10−14 |

| Men | 67% | 67% | 0.90 |

| 24 h-AER (mg)** | 18 (5–269) | 908 (26–5437) | 4.5 × 10−38 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 99 (62–152) | 50 (13–112) | 3.6 × 10−27 |

| Retinopathy | 20% | 78% | 7.8 × 10−16 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 23% | 49% | 6.4 × 10−6 |

| eGDR (mg/kg per min) | 6.6 (2.3–10.3) | 4.4 (2.5–7.0) | 1.7 × 10−13 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication | 29% | 95% | <10−17 |

| Lipid medication | 10% | 20% | 0.011 |

Median and 95% interval are reported for continuous variables. Abbreviations: type 1 diabetes (T1DM), urinary albumin excretion rate (AER), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), efficient glucose disposal rate (eGDR). * Hospital records. ** Central laboratory

The metabolic syndrome was defined according to the NCEP ATP III criteria and glomerular filtration rate was estimated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula. Efficient glucose disposal rate was estimated according to the Williams-Orchard formula 24.4–12.97 × waist-hip ratio −3.39 × hypertension −0.60 × hemoglobin A1c, where hypertension was defined as systolic/diastolic >140/90 mmHg or anti-hypertensive medication.

The proton NMR experiments were performed on a platform with three molecular windows (Mäkinen et al. 2008b; Tukiainen et al. 2008). Two windows were applied to native serum: the LIPO window yields information on lipoprotein subclasses and the LMWM window on a number of low-molecular-weight metabolites. The third window, denoted by LIPID, was applied to serum lipid extract to measure the serum lipid constituents and the diversity of fatty acid saturation. The current methodological and metabolite details for the serum NMR metabolomics, including spectral characteristics and metabolite assignments for all the three molecular windows, have been published previously (Inouye et al. 2010). Information on other biochemical and clinical variables can be found in (Mäkinen et al. 2008a).

Odds ratios for kidney disease were calculated by univariate logistic regression for each continuous variable (clinical, biochemical and NMR), respectively. Before analysis, the variables were rank transformed to produce comparable results. Adjustments for age, diabetes duration and gender were made by linear regression. Statistical significance and 95% confidence intervals were estimated by bootstrap simulation. The reported P-values are not corrected for multiple testing, but the Bonferroni significance limit is listed in the figure and table captions. The associations between continuous variables and 24 h-AER were estimated by the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Multivariate linear regression was applied to two sets of variables that were chosen based on prior biological knowledge. The first set includes multivariate formulas for the metabolic syndrome, glomerular filtration and glucose disposal rate. The second set contains directly measured quantities such as blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c and serum creatinine that reflect established vascular risk factors. Set 1 represents a clinically motivated dimension reduction, whereas Set 2 works as an a priori variable selection. We also tested ridge regression and projection to latent structures (PLS), however, neither method could produce robust estimates for the regression coefficients due to the collinearity between the variables (data not shown).

Results and discussion

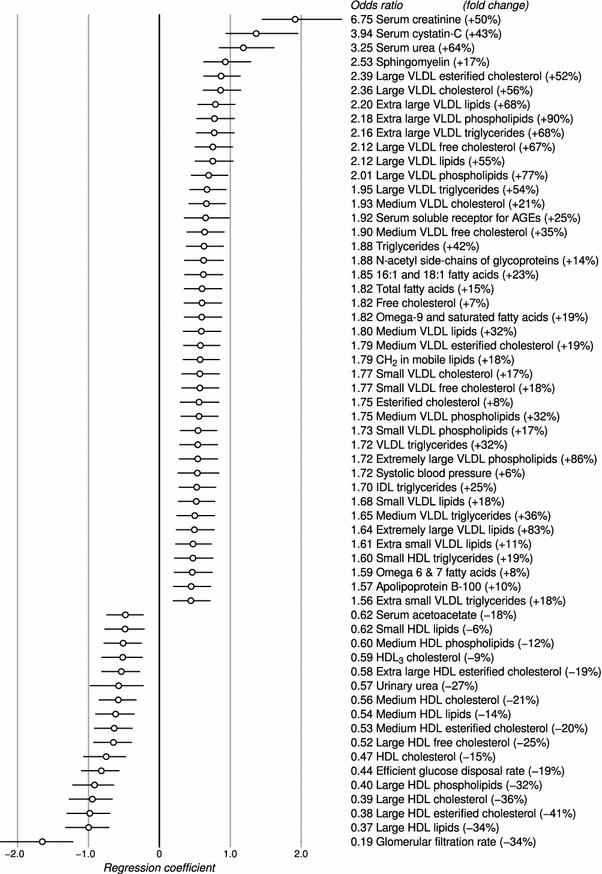

Figure 1 shows the logistic odds ratios (OR) for kidney disease—adjusted by diabetes duration, age and gender—for a subset of variables. The full list is available in Supplement 1. Serum creatinine, cystatin-C and urea are cleared by the kidneys, so a reduction in the filtration capacity has a direct effect on their concentrations (OR ≥ 3.25, P ≤ 3.4 × 10−8), and on the creatinine-based estimate of glomerular filtration rate (OR = 0.19, P = 8.2 × 10−11).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios for diabetic kidney disease, adjusted by diabetes duration, age and gender. The circles indicate logarithmic ORs (regression coefficients in the logistic model) and the horizontal lines show the 95% interval. The fold change was calculated by dividing the median concentration difference (after adjustments) between the cases and controls by the median concentration in the control group. Only those variables that reached Bonferroni multiple testing significance are included (P < 0.00038)

Sphingomyelin (OR = 2.53, P = 1.5 × 10−8) and large HDL particles (OR ≤ 0.40, P ≤ 3.1 × 10−10) are the strongest regressors after the established kidney biomarkers. Furthermore, medium HDL particles (OR ≤ 0.60, P ≤ 6.6 × 10−5) and lipids in small HDL (OR = 0.62, P = 0.00031) are inversely associated with kidney disease. Extra large and large VLDL particles have the highest ORs after sphingomyelin (OR ≥ 1.95, P ≤ 1.4 × 10−7). Monounsaturated 16:1 and 18:1 and omega-9 and saturated fatty acids have a stronger association with kidney disease (OR ≥ 1.82, P ≤ 3.5 × 10−6) than omega-6 and 7 (OR = 1.59, P = 0.00029), 18:2 (no association), omega-3 (no association), 22:6 (no association) or other polyunsaturated fatty acids (OR = 0.76, P = 0.020).

Odds ratios for retinopathy were also estimated by logistic regression: only 24 h-AER (OR = 1.75, P = 9.3 × 10−6), serum creatinine (OR = 1.52, P = 0.00028), efficient glucose disposal rate (OR = 0.55, P = 2.6 × 10−6) and glomerular filtration (OR = 0.62, P = 5.4 × 10−5) were significant regressors after adjusting for diabetes duration, age and gender.

To complement the categorical analysis, we also calculated correlations between the centrally measured continuous 24 h-AER, and the other clinical and biochemical variables. Table 2 highlights the important correlations and the full list is available in Supplement 2. Serum creatinine is strongly correlated with 24 h-AER (r = 0.73, P < 10−17), as expected. Sphingomyelin is again the top lipid variable (r = 0.42, P = 1.5 × 10−14), followed by systolic blood pressure, total triglycerides and large VLDL cholesterol. Glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol in large HDL and efficient glucose disposal rate are inversely associated with 24 h-AER.

Table 2.

A representative set of variables that are significantly correlated with 24 h-AER. Correlation was measured by the Spearman coefficient and the Bonferroni multiple testing limit is at P < 0.00038

| Adjusted by diabetes duration, age and gender | Unadjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | P-value | Correlation | P-value | |

| Serum creatinine | 0.73 | <10−17 | 0.52 | <10−17 |

| Sphingomyelin | 0.42 | 1.5 × 10−14 | 0.43 | 6.7 × 10−16 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.31 | 4.7 × 10−8 | 0.32 | 1.5 × 10−8 |

| Triglycerides | 0.30 | 3.7 × 10−7 | 0.38 | 1.6 × 10−10 |

| Large VLDL cholesterol | 0.30 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 0.29 | 1.4 × 10−7 |

| Free cholesterol | 0.29 | 3.0 × 10−7 | 0.32 | 9.2 × 10−9 |

| Omega-9 and saturated fatty acids | 0.26 | 3.3 × 10−6 | 0.33 | 1.8 × 10−9 |

| Omega-6 and 7 fatty acids | 0.26 | 5.3 × 10−6 | 0.26 | 4.3 × 10−6 |

| IDL triglycerides | 0.22 | 0.00011 | 0.27 | 1.8 × 10−6 |

| Serum adiponectin | 0.15 | 0.017 | 0.26 | 2.4 × 10−5 |

| Phosphoglycerides | 0.12 | 0.036 | 0.16 | 0.0041 |

| Diabetes duration | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.38 | 4.2 × 10−12 |

| Phosphatidylcholine | −0.02 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.96 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | −0.05 | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.60 |

| Fatty acid length | −0.20 | 0.00040 | −0.25 | 6.6 × 10−6 |

| Medium HDL cholesterol | −0.25 | 1.2 × 10−5 | −0.28 | 5.7 × 10−7 |

| HDL cholesterol | −0.31 | 2.1 × 10−7 | −0.27 | 4.9 × 10−6 |

| Large HDL cholesterol | −0.33 | 3.6 × 10−9 | −0.32 | 7.7 × 10−9 |

| Efficient glucose disposal rate | −0.33 | 8.2 × 10−9 | −0.51 | <10−17 |

| Glomerular filtration rate | −0.45 | 3.3 × 10−16 | −0.43 | 1.2 × 10−14 |

We chose two sets of variables that represent established risk factors for diabetic kidney disease to explain the covariance between sphingomyelin and 24 h-AER (Table 3). Set 1 includes derived clinical traits (such as the metabolic syndrome), whereas Set 2 includes measures that represent diagnostic components: waist circumference for obesity, systolic blood pressure for hypertension, hemoglobin A1c for glycemic control, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol for dyslipidemia and serum creatinine for kidney function. Sphingomyelin is a statistically significant trait in both models (P ≤ 1.8 × 10−5), which suggests that it may reflect previously undetected biological phenomena that are specific to albuminuria.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients for biologically motivated models of 24 h-AER

| Beta | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 of 24 h-AER | ||

| Sphingomyelin | 0.22 | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| T1DM duration | 0.011 | 0.42 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 0.12 | 0.0042 |

| eGDR | −0.32 | 1.4 × 10−10 |

| eGFR | −0.28 | 5.6 × 10−6 |

| Model 2 of 24 h-AER | ||

| Sphingomyelin | 0.22 | 1.1 × 10−5 |

| T1DM duration | 0.19 | 0.00013 |

| Male gender | 0.0012 | 0.50 |

| Waist | 0.057 | 0.173 |

| Systolic BP | 0.084 | 0.047 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 0.15 | 0.0011 |

| Triglycerides | 0.031 | 0.33 |

| HDL cholesterol | −0.13 | 0.0046 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.30 | 7.8 × 10−6 |

All data were rank transformed and normalized prior to analyses and the regression coefficients are in standardized units. Model 1 explained 44.1%, and Model 2 explained 41.9% of 24 h-AER variance. Without sphingomyelin (i.e., sphingomyelin values were shuffled randomly), the two models explained 40.5 and 38.8% of the 24 h-AER variance, respectively. Abbreviations: type 1 diabetes (T1DM), urinary albumin excretion rate (AER), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), efficient glucose disposal rate (eGDR)

Models of the binary kidney disease diagnosis and retinopathy are available in Supplement 3. Kidney disease is associated with glomerular filtration and sphingomyelin in Set 1, and with serum creatinine, HDL cholesterol, sphingomyelin and diabetes duration in Set 2. Retinopathy is strongly related to diabetes duration, but not to sphingomyelin.

Sphingomyelin is correlated with glomerular filtration rate (r = –0.32, P < 10−6), but this study cannot ascertain the causal relationships between albuminuria, declining kidney function and lipotoxicity. The selection of study subjects is another limitation: although matched for gender, the patients without kidney disease had a shorter diabetes duration. It is therefore possible that some of the controls were in an early phase of kidney disease, which could have diluted the results.

A recent animal study demonstrated how the manipulation of the sphingolipid pathway could alleviate kidney disease: untreated mice on a high-fat diet developed insulin resistance and albuminuria, but a pharmacological intervention reduced the effects (Boini et al. 2010). By inhibiting the conversion of sphingomyelin into ceramide, the authors were able to significantly decrease glomerular injury and restore urinary albumin excretion rate to normal range.

The proportional increase of sphingomyelin in the kidney disease group was modest (+17% when adjusted by aging and gender) and much of the variance was shared with other clinical characteristics, which suggests that excess circulating sphingomyelin might be a by-product of the disease process rather than an active initiator. In fact, excess saturated fatty acids may be the underlying cause: they are substrates for sphingolipid synthesis, they promote lipotoxicity (production of ceramides) and are also linked to insulin resistance (Bunn et al. 2010; Kennedy et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2009). The NMR method cannot distinguish between omega-9 and saturated fatty acid chains, but the combination was nevertheless significantly correlated with clinical kidney disease (Fig. 1) and 24 h-AER (Table 2), whereas polyunsaturated fatty acids such as 18:2 or 22:6 showed no association.

Concluding remarks

Sphingomyelin emerged as a significant biochemical covariate of urinary albumin excretion in human type 1 diabetes, and the strongest lipid regressor for kidney disease. We also reproduced the associations between macroalbuminuria and high triglycerides, excess serum fatty acids and altered VLDL-HDL balance. Phospholipids or polyunsaturated fatty acids were not covariates of albuminuria. Our results are supported by animal data, which suggests that sphingolipids may reflect some of the molecular links between microvascular injury, insulin resistance, and saturated fatty acids. Further research of the sphingolipid pathway may thus yield more sensitive phenotyping measures and new pharmacological options to ease the burden of diabetic complications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 Results from univariate logistic regression of diabetic kidney disease. A separate model was constructed for each of the continuous variables. Adjustments were made for age, diabetes duration and gender. (XLS 17 kb)

Supplementary material 2 Spearman correlation coefficients between the continuous variables and 24 h-AER. Adjustments were made for age, diabetes duration and gender. (XLS 21 kb)

Supplementary material 3 Regression coefficients for biologically motivated models of diabetic kidney disease and retinopathy. All data were rank transformed and normalized prior to analyses and the regression coefficients are in standardized units. (DOC 27 kb)

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Grants from the Folkhälsan Research Foundation, the Wilhelm and Else Stockmann Foundation, the Liv och Hälsa Foundation and the CEED3 partnership within the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Union (project 223211). The work was also supported by the National Graduate School of Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology in University of Eastern Finland (TT), the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation (AJK), the Academy of Finland (PS and MAK) and the Finnish Cardiovascular Research Foundation (MAK).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Ville-Petteri Mäkinen, Tuulia Tynkkynen, Pasi Soininen, Carol Forsblom, Tomi Peltola, Antti J Kangas, Per-Henrik Groop, Mika Ala-Korpela on behalf of the FinnDiane Study Group.

References

- Ala-Korpela M. Potential role of body fluid 1H NMR metabonomics as a prognostic and diagnostic tool. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2007;7:761–773. doi: 10.1586/14737159.7.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdade JD, Subbaiah PV. Whole-plasma and high-density lipoprotein subfraction surface lipid composition in IDDM men. Diabetes. 1989;38:1226–1230. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.38.10.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best LG, Zhang Y, Lee ET, Yeh J, Cowan L, Palmieri V, Roman M, Devereux RB, Fabsitz RR, Tracy RP, Robbins D, Davidson M, Ahmed A, Howard BV. C-reactive protein as a predictor of cardiovascular risk in a population with a high prevalence of diabetes: The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112:1289–1295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.489260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boini KM, Zhang C, Xia M, Poklis JL, Li P. Role of sphingolipid mediator ceramide in obesity and renal injury in mice fed a high-fat diet. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;334:839–846. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn RC, Cockrell GE, Ou Y, Thrailkill KM, Lumpkin CKJ, Fowlkes JL. Palmitate and insulin synergistically induce IL-6 expression in human monocytes. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2010;9:73. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-9-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao JJ, Arnold AM, Manolio TA, Polak JF, Psaty BM, Hirsch CH, Kuller LH, Cushman M. Association of carotid artery intima-media thickness, plaques, and c-reactive protein with future cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2007;116:32–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.645606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fievet C, Ziegler O, Parra HJ, Mejean L, Fruchart JC, Drouin P. Depletion in choline containing phospholipids of lpB particles in adequately controlled type I insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes & Metabolism. 1990;16:64–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsblom C, Harjutsalo V, Thorn LM, Wadén J, Tolonen N, Saraheimo M, Gordin D, Moran JL, Thomas MC, Groop PH. Competing-risk analysis of ESRD and death among patients with type 1 diabetes and macroalbuminuria. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2011;22:537–544. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TE, Bewley MC, Unrath KA, Pedersen MM, Anderson RE, Jung DY, Jefferson LS, Kim JK, Bronson SK, Flanagan JM, Kester M. Circulating sphingolipid biomarkers in models of type 1 diabetes. Journal of Lipid Research. 2011;52:509–517. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M010595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groop PH, Forsblom C, Thomas MC. Mechanisms of disease: Pathway-selective insulin resistance and microvascular complications of diabetes. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;1:100–110. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groop PH, Thomas MC, Moran JL, Wadèn J, Thorn LM, Mäkinen VP, Rosengård-Bärlund M, Saraheimo M, Hietala K, Heikkilä O, Forsblom C. The presence and severity of chronic kidney disease predicts all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:1651–1658. doi: 10.2337/db08-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T. Diabetic nephropathy: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:164–176. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks AA, Pramstaller PP, Johansson A, Vitart V, Rudan I, Ugocsai P, Aulchenko Y, Franklin CS, Liebisch G, Erdmann J, Jonasson I, Zorkoltseva IV, Pattaro C, Hayward C, Isaacs A, Hengstenberg C, Campbell S, Gnewuch C, Janssens ACW, Kirichenko AV, König IR, Marroni F, Polasek O, Demirkan A, Kolcic I, Schwienbacher C, Igl W, Biloglav Z, Witteman JCM, Pichler I, Zaboli G, Axenovich TI, Peters A, Schreiber S, Wichmann H, Schunkert H, Hastie N, Oostra BA, Wild SH, Meitinger T, Gyllensten U, van Duijn CM, Wilson JF, Wright A, Schmitz G, Campbell H. Genetic determinants of circulating sphingolipid concentrations in european populations. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye M, Kettunen J, Soininen P, Silander K, Ripatti S, Kumpula LS, Hämäläinen E, Jousilahti P, Kangas AJ, Männistö S, Savolainen MJ, Jula A, Leiviskä J, Palotie A, Salomaa V, Perola M, Ala-Korpela M, Peltonen L. Metabonomic, transcriptomic, and genomic variation of a population cohort. Molecular Systems Biology. 2010;6:441. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain SK, McVie R, Meachum ZD, Smith T. Effect of LDL+VLDL oxidizability and hyperglycemia on blood cholesterol, phospholipid and triglyceride levels in type-I diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2000;149:69–73. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins AJ, Lyons TJ, Zheng D, Otvos JD, Lackland DT, McGee D, Garvey WT, Klein RL. Lipoproteins in the DCCT/EDIC cohort: Associations with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney International. 2003;64:817–828. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A, Martinez K, Chuang C, LaPoint K, McIntosh M. Saturated fatty acid-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue: Mechanisms of action and implications. Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139:1–4. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.098269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Sharp SJ, Wexler DJ, Adler AI. Dietary intake of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid and diabetic nephropathy: Cohort analysis of the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1454–1456. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithovius R, Harjutsalo V, Forsblom C, Groop PH. Cumulative cost of prescription medication in outpatients with type 1 diabetes in Finland. Diabetologia. 2011;54:496–503. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1999-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen VP, Soininen P, Forsblom C, Parkkonen M, Ingman P, Kaski K, Groop PH, Ala-Korpela M. Diagnosing diabetic nephropathy by 1H NMR metabonomics of serum. MAGMA. 2006;19:281–296. doi: 10.1007/s10334-006-0054-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen VP, Forsblom C, Thorn LM, Wadén J, Gordin D, Heikkilä O, Hietala K, Kyllönen L, Kytö J, Rosengård-Bärlund M, Saraheimo M, Tolonen N, Parkkonen M, Kaski K, Ala-Korpela M, Groop PH. Metabolic phenotypes, vascular complications, and premature deaths in a population of 4,197 patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2480–2487. doi: 10.2337/db08-0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen VP, Soininen P, Forsblom C, Parkkonen M, Ingman P, Kaski K, Groop PH, Ala-Korpela M. 1H NMR metabonomics approach to the disease continuum of diabetic complications and premature death. Molecular Systems Biology. 2008;4:167. doi: 10.1038/msb4100205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori TA, Vandongen R, Masarei JR, Stanton KG, Dunbar D. Dietary fish oils increase serum lipids in insulin-dependent diabetics compared with healthy controls. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 1989;38:404–409. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(89)90188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish NJ, Wang SL, Stevens LK, Fuller JH, Keen H. Mortality and causes of death in the WHO multinational study of vascular disease in diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44(Suppl 2):S14–S21. doi: 10.1007/PL00002934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oresic M, Simell S, Sysi-Aho M, Näntö-Salonen K, Seppänen-Laakso T, Parikka V, Katajamaa M, Hekkala A, Mattila I, Keskinen P, Yetukuri L, Reinikainen A, Lähde J, Suortti T, Hakalax J, Simell T, Hyöty H, Veijola R, Ilonen J, Lahesmaa R, Knip M, Simell O. Dysregulation of lipid and amino acid metabolism precedes islet autoimmunity in children who later progress to type 1 diabetes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:2975–2984. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperi C, Kalofoutis C, Tzivras M, Troupis T, Skenderis A, Kalofoutis A. Effects of hemodialysis on serum lipids and phospholipids of end-stage renal failure patients. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2004;265:57–61. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000044315.74038.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraheimo M, Teppo A, Forsblom C, Fagerudd J, Groop PH. Diabetic nephropathy is associated with low-grade inflammation in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1402–1407. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seigneur M, Freyburger G, Gin H, Claverie M, Lardeau D, Lacape G, Le Moigne F, Crockett R, Boisseau MR. Serum fatty acid profiles in type I and type II diabetes: Metabolic alterations of fatty acids of the main serum lipids. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 1994;23:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soedamah-Muthu SS, Chang Y, Otvos J, Evans RW, Orchard TJ. Lipoprotein subclass measurements by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy improve the prediction of coronary artery disease in type 1 diabetes. A prospective report from the Pittsburgh epidemiology of diabetes complications study. Diabetologia. 2003;46:674–682. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler M, Auinger M, Anderwald C, Kästenbauer T, Kramar R, Feinböck C, Irsigler K, Kronenberg F, Prager R. Long-term mortality and incidence of renal dialysis and transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91:3814–3820. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers SA. Sphingolipids and insulin resistance: The five Ws. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2010;21:128–135. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283373b66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmi BK, Hasty AH. The role of chemokines in recruitment of immune cells to the artery wall and adipose tissue. Vascular Pharmacology. 2010;52:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn LM, Forsblom C, Fagerudd J, Thomas MC, Pettersson-Fernholm K, Saraheimo M, Wadén J, Rönnback M, Rosengård-Bärlund M, Björkesten CA, Taskinen M, Groop PH. Metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetes: Association with diabetic nephropathy and glycemic control (the Finndiane Study) Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2019–2024. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolonen N, Forsblom C, Thorn L, Wadén J, Rosengård-Bärlund M, Saraheimo M, Feodoroff M, Mäkinen VP, Gordin D, Taskinen M, Groop PH. Lipid abnormalities predict progression of renal disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2522–2530. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukiainen T, Tynkkynen T, Mäkinen VP, Jylänki P, Kangas A, Hokkanen J, Vehtari A, Gröhn O, Hallikainen M, Soininen H, Kivipelto M, Groop PH, Kaski K, Laatikainen R, Soininen P, Pirttilä T, Ala-Korpela M. A multi-metabolite analysis of serum by 1H NMR spectroscopy: Early systemic signs of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;375:356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watała C, Jóźwiak Z. The phospholipid composition of erythrocyte ghosts and plasma lipoproteins in diabetes type 1 in children. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1990;188:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Badeanlou L, Bielawski J, Roberts AJ, Hannun YA, Samad F. Central role of ceramide biosynthesis in body weight regulation, energy metabolism, and the metabolic syndrome. American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;297:E211–E224. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.91014.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 Results from univariate logistic regression of diabetic kidney disease. A separate model was constructed for each of the continuous variables. Adjustments were made for age, diabetes duration and gender. (XLS 17 kb)

Supplementary material 2 Spearman correlation coefficients between the continuous variables and 24 h-AER. Adjustments were made for age, diabetes duration and gender. (XLS 21 kb)

Supplementary material 3 Regression coefficients for biologically motivated models of diabetic kidney disease and retinopathy. All data were rank transformed and normalized prior to analyses and the regression coefficients are in standardized units. (DOC 27 kb)