Abstract

Clopidogrel in association with aspirine is considered state of the art of medical treatment for acute coronary syndrome by reducing the risk of new ischemic events. Concomitant treatment with proton pump inhibitors in order to prevent gastrointestinal side effects is recommended by clinical guidelines. Clopidogrel needs metabolic activation predominantly by the hepatic cytochrome P450 isoenzyme Cytochrome 2C19 (CYP2C19) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are extensively metabolized by the CYP2C19 isoenzyme as well. Several pharmacodynamic studies investigating a potential clopidogrel-PPI interaction found a significant decrease of the clopidogrel platelet antiaggregation effect for omeprazole, but not for pantoprazole. Initial clinical cohort studies in 2009 reported an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events, when under clopidogrel and PPI treatment at the same time. These observations led the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medecines Agency to discourage the combination of clopidogrel and PPI (especially omeprazole) in the same year. In contrast, more recent retrospective cohort studies including propensity score matching and the only existing randomized trial have not shown any difference concerning adverse cardiovascular events when concomitantly on clopidogrel and PPI or only on clopidogrel. Three meta-analyses report an inverse correlation between clopidogrel-PPI interaction and study quality, with high and moderate quality studies not reporting any association, rising concern about unmeasured confounders biasing the low quality studies. Thus, no definite evidence exists for an effect on mortality. Because PPI induced risk reduction clearly overweighs the possible adverse cardiovascular risk in patients with high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, combination of clopidogrel with the less CYP2C19 inhibiting pantoprazole should be recommended.

Keywords: Clopidogrel, Thienopyridine, Proton pump inhibitors, Drug interaction, Platelet reactivity, Antiplatelet therapy, Cytochromes, Acute coronary syndrome, Gastrointestinal bleeding

CLOPIDOGREL AND PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS - WHERE DO WE STAND IN 2011?

Clopidogrel in association with Aspirine has become the basis of pharmaceutical treatment in patients treated either medically or with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), by significantly reducing the risk of new ischemic cardiovascular events[1].

To prevent gastrointestinal bleeding as a drug-induced side effect, proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are often associated with clopidogrel use. This strategy is recommended by consensus guidelines[2] and endorsed by a recent meta-analysis, especially for patients taking dual antiplatelet therapy but in a lesser extent for those on clopidogrel alone due to sparse data[3-5]. Gilard et al[6,7] first reported in 2006 and 2008 a significant decrease of the clopidogrel effect in association with omeprazole in vitro. In opposite to that, no decrease was found in further pharmacodynamic studies for pantoprazole or esomeprazole[8-13]. Several retrospective observational studies showed an increased risk of new cardiovascular events in patients on clopidogrel-PPI association[14-22], thus leading the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to recommend to avoid the clopidogrel-PPI combination, especially with omeprazole[23,24]. More recently, one randomized double-blind trial[25], one post-hoc analysis of a randomized double-blind trial comparing prasugrel with clopidogrel[26] and several predominantly propensity matched cohort studies[27-35] have not shown clinically relevant adverse cardiovascular interaction between clopidogrel and PPI. Moreover, three recent meta-analyses, one by Kwok et al[36] reviewing 23 studies with the majority in abstract form, one by Siller-Matula et al[37] including 25 studies and the most recent by Lima et al[38] reviewing 18 studies pointed out that an elevated risk of bias was present in these studies indicating a possible interaction between clopidogrel and PPI. Furthermore, there was no significance for a drug interaction by analysing propensity matched and randomized trials.

The aim of this review is to focus on these recent studies, in order to reevaluate the present recommendations.

CLOPIDOGREL

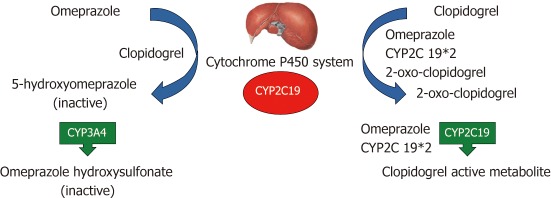

Clopidogrel is a thienopyridine, inhibiting adenosine diphosphate (ADP) induced platelet activation by blocking the P2Y12 receptor on the platelet surface. It is a prodrug that needs to be metabolized in an intrahepatic two-step oxidative process. First, the cytochrome P450 isoenzymes CYP1A2, CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 form 2-oxo-clopidogrel, which is then oxidized by CYP2B6, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 to the clopidogrel active metabolite. The further formation of a disulfide bond with the P2Y12 receptor unables the binding of ADP and finally platelet activation[12,39]. This is associated with dephosphorylation of intraplatelet vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), providing an index of platelet reactivity to clopidogrel: the higher the platelet reactivity index (PRI), the less important the antithrombotic effect of clopidogrel[7]. Cytochrome P450 CYP2C19 seems to be of major importance in the metabolisation and activation of clopidogrel (Figure 1). Recent studies investigating the genetic polymorphism of the CYP2C19 allele have found a decreased platelet inhibition and increased cardiovascular risk in patients treated by clopidogrel, when carriers of even one reduced function CYP2C19 allele[40-42]. The CYP2C19*2 mutation was the most frequent variant found in the poor metabolizer (decreased platelet inhibition) group[43-45]. The prevalence of reduced function alleles differs among various populations, while an increase effect is observed from West to East: In the Caucasian population, 30%-40% of the normal function *1/*2 genotype and 2%-5% of the reduced function *2/*2 genotype are reported, whereas in East Asian and Chinese populations up to 24% of the poor metabolizing genotypes *2/*2, *2/*3 and *3/*3 are present[46-48].

Figure 1.

Potential intrahepatic mechanism of Proton pump inhibitor-clopidogrel interaction by the example of omeprazole (adapted from Tantry et al[50]). CYP2C19: Cytochrome 2C19; CYP2C19*2: Poor metabolizing cytochrome 2C19 isoenzyme.

PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS

PPI are benzimidazole derivates consisting of two heterocyclic moieties linked via a methylsulfinyl group. Being weak bases, they reach the parietal cell membrane as pro-drugs and can thereby cross cell membrane to accumulate in the canalicular space, where the environment is highly acid. After a two step pronation, the drug reacts with cysteine sulfhydryls on the gastric H+/K+-ATPase by forming covalent disulfide bonds and inhibiting its activity[49-53]. So far, we dispose of five different PPIs on the market: omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole. Each among them is mainly metabolized by the intrahepatic P450 cytochrome system, especially CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, inhibiting them competitively. Interestingly, in vitro studies showed important differences in the inhibition of CYP2C19, with lansoprazole and omeprazole being the most powerful inhibitors while pantoprazole and rabeprazole are the less potent inhibitors[49,54,55]. Of note, only pantoprazole showed significant acid inhibition after a single dose in the fast metabolizing genotype CYP2C19*1[46].

PHARMACODYNAMIC STUDIES ON CLOPIDOGREL- PPI INTERACTION

Gilard et al[6] demonstrated in 2006 an in vitro reduction of the antiaggregatory activity of clopidogrel in patients after coronary revascularisation under PPI treatment. The same group ran out the randomized double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirine) trial in 2008: 124 patients undergoing elective coronary artery stent implantation receiving 75 mg of aspirine and clopidogrel daily, were randomized to receive either omeprazole 20 mg/d or placebo. The clopidogrel effect was assessed by measuring the phosphorylated VASP expressed in the PRI on day 1 and 7. On day 7, the mean PRI was significantly higher in the omeprazole-associated group (51.4% vs 39.8%, P > 0.0001), indicating less effective platelet antiaggregation. To investigate whether this potential interaction was due to a class effect, Cuisset et al[11] compared in the PACA (PPI And Clopidogrel Association) study 104 patients undergoing coronary stent implantation for non-ST-elevation ACS by randomizing them to a 20 mg omeprazole or pantoprazole treatment in association with 75 mg of aspirine and 150 mg of clopidogrel. After 1 mo, the VASP PRI was significantly lower in the pantoprazole group (36% ± 20% vs 48% ± 17%, P = 0.007), suggesting that pantoprazole, being a less potent CYP2C19 inhibitor, leads to a lower decrease of the clopidogrel antithrombotic effect. These results were confirmed in a prospective observational study, including a multivariable logistic regression analysis on 300 patients with coronary artery disease undergoing PCI and being already under aspirine 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d for at least 5 d. No difference was found for the VASP-PRI and the ADP induced platelet aggregation (ADP Ag) either between the PPI and no-PPI-group (51% vs 49%, P = 0.724) or between the different PPIs (pantoprazole and esomeprazole)[8]. In the same line, a prospective observational study including 336 patients undergoing coronary stent implantation showed no difference in ADP induced platelet aggregation between patients treated concomitantly by clopidogrel (600 mg loading and 75 mg maintenance dose) and pantoprazole vs clopidogrel only (OR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.31-1.13). For omeprazole and esomeprazole, a non significant increase in platelet aggregation persisted even after multiple adjustment (OR 1.84, 95% CI: 0.64-5.31), but due to the relatively small number of patients (26 vs 122 pantoprazole users), definite conclusions couldn’t be drawn[13]. The authors of the post-hoc analysis of the PRINCIPLE (Prasugrel In Comparison to Clopidogrel for Inhibition of Platelet Activation and Aggregation)-TIMI 44 study evaluated the impact of concomitant PPI use in 201 patients undergoing planned PCI and randomly assigned to either prasugrel (a new third generation thienopyridine) or high dose clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose and 150 mg/d maintenance dose) treatment. Fifty-six patients (26.4 %) were recorded to take a PPI at the time of randomization and the mean inhibition of platelet aggregation measured by ADP induced platelet aggregation was significantly lower at 2, 6 and 24 h after the loading dose, with a non-significant trend still persisting after 15 d. For prasugrel, no significant lowering of the mean inhibition of platelet aggregation was observed in the first 24 h, becoming only significant after 15 d in patient treated by PPI[26]. Recently, Angiolillo et al[12] conducted four randomized placebo-controlled crossover comparison studies among 282 healthy subjects, addressing the questions whether the PPI-clopidogrel interaction should be considered as a class effect or is rather due to more or less potent CYP2C19 inhibition and if a time interval between clopidogrel and PPI administration might diminish the inhibitory effect as evoked by the rapid metabolization of clopidogrel and omeprazole. After randomization in either interventional or placebo groups, the interventional arm entered a two period (clopidogrel only and clopidogrel with PPI) crossover study with four interventions during the clopidogrel-PPI period: The first study investigated an interaction between clopidogrel (300 mg loading and 75 mg maintenance dose) and omeprazole 80 mg/d when administered simultaneously. Study 2 investigated the administration of clopidogrel and omeprazole staggered by 12 h and study 3 an increased clopidogrel dose (600 mg loading and 150 mg maintenance dose) with omeprazole 80 mg/d. Finally, study 4 used a standard clopidogrel dose with pantoprazole 80 mg/d. Dosages of the active metabolite of clopidogrel (clopi H4) were significantly decreased in study 1, 2 and 3 while ADP induced platelet aggregation as well as VASP-PRI were significantly increased, indicating a less effective platelet antiaggregation in patients treated concomitantly with clopidogrel and omeprazole. Of note, these results were irrespective of the administration time or the clopidogrel dose. In contrast, the decrease of clopi H4 (40%, P < 0.001 for omeprazole and 14%, P < 0.002 for pantoprazole) was smaller in study 4 as well as the increase of ADP induced platelet aggregation, both differences remaining statistically significant. The increase of VASP-PRI was not significant when treated with pantoprazole, leading the authors to conclude that the clopidogrel-PPI interaction was not a class effect, whereas the combination with pantoprazole was a more optimal treatment option[12]. However, omeprazole was given at 80 mg per day, which represents 2 to 4 times the dose commonly prescribed, leaving unclear the hypothesis of a possible interaction when using standard doses. Furthermore, other molecules like rabeprazole, which does not inhibit the CYP2C19 isoenzyme, haven’t been tested. In the same line, Ferreiro et al[56] conducted two supplementary randomized crossover studies in healthy subjects: In the first study, 20 volunteers received a 600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg of clopidogrel combined with 40 mg of omeprazole concomitantly or staggered by 8-12 h with a crossover washout period after a 2-4 wk followed by 1 wk of clopidogrel alone after a new washout period: No difference was observed in VASP-PRI after 1 wk between the concomitant and the staggered omeprazole administration, but PRI was significantly lower in the clopidogrel alone period compared with the omeprazole period, irrespective of the timing of administration (comcomitant omeprazole: P = 0.02; staggered omeprazole: P = 0.001). In the second study, 80 mg of pantoprazole were administered with the same regimen, but no differences in VASP-PRI were found between a concomitant or staggered administration of pantoprazole. Moreover, no difference was noted between clopidogrel alone and clopidogrel plus pantoprazole after 1 wk of treatment. The authors concluded that a time interval between the administration of clopidogrel and PPI doesn’t afford any benefit and that pantoprazole seems to be a safer choice when combined with clopidogrel[57] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of important pharmacodynamic studies on the clopidogrel-proton pump inhibitor interaction

| Study | PPIs used | Population | Primary outcome | Author’s conclusions |

| Gilard et al[7] OCLA study (double-blind, placebo-controled, randomized) | Omeprazole | 124 patients undergoing elective coronary stent implantation | VASP-PRI on 7 d | Omeprazole significantly decreases clopidogrel inhibitory effect |

| Cuisset et al[11] PACA study (prospective, randomized) | Omeprazole vs Pantoprazole | 104 NSTE-ACS patients undergoing coronary stenting | VASP-PRI/ADP-Ag after 1 mo | Significantly better platelet response under pantoprazole (VASP-PRI), no difference for ADP-Ag |

| O’Donoghue et al[26] PRINCIPLE-TIMI 44 (post hoc analysis of a RCT) | Not specified | 201 patients undergoing planned PCI | ADP Ag | Mean inhibition of platelet aggregation significantly lower for patients on PPI |

| Siller-Matula et al[8] (prospective observational) | Pantoprazole esomeprazole | 300 patients with CAD undergoing PCI | VASP-PRI/ADP-Ag in the catheter laboratory | No association of PPIs with impaired response to clopidogrel |

| Neubauer et al[13] (prospective observational) | Pantoprazole omeprazole esomeprazole | 336 patients undergoing coronary stent implantation | ADP Ag | Pantoprazole does not diminish the antiplatelet effectiveness of clopidogrel |

| Angiolillo et al[12] (placebo controlled, randomized, cross-over) | Omeprazole pantoprazole | 282 healthy subjects | Clopi H4 ADP Ag VASP-PRI after 5 d | Presence of a metabolic drug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole but not for pantoprazole |

VASP-PRI: Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein platelet reactivity index; NSTE-ACS: Non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome; ADP Ag: Adenosine DiPhospate induced platelet aggregation; CAD: Coronary artery disease; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; OCLA: Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirine; PACA: PPI and clopidogrel association; PRINCIPLE-TIMI: Prasugrel in comparison to clopidogrel for inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation-TIMI.

CLINICAL TRIALS ON CLOPIDOGREL- PPI INTERACTION

In 2009, Ho et al[15] published a retrospective cohort study including 8205 patients hospitalized for ACS in Veterans Affairs Hospitals. Analysis of prescription records identified 63.9% of patients being concomitantly under clopidogrel and PPI with a mean follow-up of 521 d. Concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPI (predominantly omeprazole and rabeprazole) was associated with an elevated risk of death or rehospitalisation for ACS after multivariable analysis (OR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.11-1.41). Of note, 98% were men and no information on the patient’s race was available. In the same line, a Canadian population-based nested case-control study based on discharge abstracts and prescription records of 13636 patients being hospitalized for ACS, found an increased risk of reinfarction when under concomitant clopidogrel and PPI use (OR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.03-1.57). An analysis according to the PPI molecule used found no association with increased myocardial reinfarction for pantoprazole users in contrast to a 40% risk increase when using other PPIs (OR 1.40, 95% CI: 1.10-1.77). This result should be interpreted carefully, due to the small number of pantoprazole users (46 of 734 reinfarction patients)[16]. Moreover, only patients aged 66 years or older were included, introducing potential age bias. Another retrospective observational study based on diagnosis and prescription records of two Dutch health insurances, included 18139 new clopidogrel users, of whom 5734 (32%) were on concomitant PPI treatment. In this particular study, patients under PPI cotherapy had a significantly higher risk for the composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke and all-cause mortality (HR 1.75, 95% CI: 1.58-1.94). In the subanalysis of secondary endpoints, PPI use was associated with a higher risk of myocardial infarction (ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation), unstable angina and all-cause mortality, but not with stroke[14]. Selection bias may be present in these two insurance databases, covering only 25% of the Dutch population. All three studies evidence significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the clopidogrel and the clopidogrel-PPI groups with significantly older patients with several comorbidities (e.g., heart failure, diabetes mellitus and renal failure) in the latter group, raising concern about unmeasured confounders in patients whith cardiovascular risk treated by PPI. In addition to that, no data about the efficacy of antihypertensive and statin treatment as well as on smoking status were available. Finally as the medication exposure was based on prescription records, drug compliance data were not available.

More recently, several studies have been designed to include propensity scores in their analysis to improve confounding adjustment. Especially confounding by indication, an important bias in pharmacoepidemiologic studies, is diminished by using propensity score matching by calculating the probability to be exposed to a treatment or not. Moreover, adjustment for unmeasured or mis-measured covariates is improved by including hundreds of items in the propensity score calibration[58]. However, by the fact that many unexposed subjects of the initial study population aren’t matched to exposed subjects and unmatched exposed subjects are excluded from the propensity matched analysis, precision of the estimated drug interaction could be decreased[59-62]. Rassen et al[31] analysed 18 565 patients aged over 65 years having been hospitalized for ACS and consecutive PCI in a retrospective cohort study based on Canadian and United states insurance records. Patients under clopidogrel and PPI had a slightly increased risk for rehospitalization for myocardial infarction or death of any cause (RR 1.26, 95% CI: 0.97- 1.63) leading the authors to conclude to no evidence of a substantial interaction. Major efforts for bias reduction have been made in this study by including only clopidogrel naïve patients, using a 7 d run-in period and a high-dimensional propensity score, permitting further adjustment for 400 additional variables empirically identified in their databases[63]. However, Aspirine use was unfortunately not measured in this coronary disease population[31]. A similar analysis was conducted on 20 596 patients of the Tennessee Medicaid program after hospitalization for ACS and PCI. Concomitant clopidogrel and PPI use was not associated with serious cardiovascular disease (HR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.82-1.19). Subanalysis concerning the different types of PPI has not found any increased risk of serious cardiovascular disease either, but confidence bounds were wide except for pantoprazole[27]. Another retrospective cohort study using the national Danish patient and prescription registry, included 56 406 patients older than 30 years and hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction. Concomitant clopidogrel and PPI users had a significant increased risk for cardiovascular death or rehospitalization for myocardial infarction and stroke compared to non-PPI users (HR 1.35, 95% CI: 1.22-1.50). In the same time, PPI users not receiving clopidogrel presented a similar increased risk (HR 1.43, 95% CI: 1.34-1.53), indicating no interaction between clopidogrel and PPI. The authors suspected that the increased cardiovascular risk in PPI users might be due to imperfectly measured differences in the baseline characteristics (lack of data on smoking status, lipid levels and body mass index)[28]. The strength of this study lies in the unselected nationwide population (patients older than 30 years hopitalized for myocardial infarction allover in Denmark) and the probably high concordance between the measured drug dispension (from data of the Danish national prescription registry) and real drug consumption due to only partial reimboursement of drug expenses and the fact that PPIs weren’t available over the counter during the study period. However, the study is based on data from 2000 to 2006 and the low antiplatelet drug exposure (only 50%-70% of patients were under aspirine and 27% under clopidogrel on follow-up) dramatically contrasts with the current practice and questions the validity of the final conclusions.

In 2011, two analyses of PCI registries, including large data on cardiovascular risk factors and comorbities, were not able to show any difference on cardiovascular events: The American Guthrie Health Off-Lable Stent (GHOST) investigators studied 2651 patients discharged after coronary stenting and found no increase of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE: death, myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularisation or stent thrombosis) for PPI users after propensity adjusted analysis (HR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.63-1.27) and in the propensity matched subgroup including 685 pairs of patients [42 (6.1%) without PPI against 40 (5.8%) with PPI; adjusted P = 0.60], the latter indicating even a trend to a protective effect of PPI treatment when under clopidogrel, perhaps due to less discontinuation of the antiaggregation as shown at the 6 mo follow-up (78% under clopidogrel in the PPI group against 70% without PPI, P = 0.0085). Furthermore, no difference according to the PPI used (omeprazole and esomeprazole) was observed[29]. Similar results came from the French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI), including 3670 post myocardial infarction patients. No increase in death, reinfarction or stroke was observed for concomitant PPI and clopidogrel use after one year (HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.90-1.08). Furthermore, no difference existed regarding the PPI used (predominantly omeprazole and esomeprazole) and the presence of no or 1 to 2 CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles. Of note, only a low number of 2 CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles patients has been integrated (44 of 1579), leaving a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcome in this group still possible[30]. Both studies are based on PCI registries with detailed data assessment on baseline until hospital discharge. In contrast, follow-up was restricted on recording the patient’s hospital readmission or death, without reliable information on medication exposure after hospitalization. The analysis restricted to the clopidogrel naïve population (2651 of 4421 respectively 2744 of 3670 patients) in order to avoid bias du to the occurrence of the index episode, limited the number of patients included, and may have underpowered the individual subgroups to detect a significant difference. Pointing out that the majority of the previous observational studies relied on discharge prescription records, Banerjee et al[32]. conducted a study on 23 200 post-PCI patients, including postdischarge drug exposure patterns using data from the Veteran Affairs Pharmacy Benefits Management database to assess drug exposure during the follow-up throughout a 6 years period. After propensity score adjustment, no difference in MACE (composite of all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction or repeated revasularisation) was observed between PPI and no PPI use in the group of continuous clopidogrel users (HR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.65-1.44). A rigorous control according to the consistency and duration of the clopidogrel and PPI exposure has been done, by revising daily exposure derived from prescription release dates and days of supply-a method considered superior to patient self-reported medication use[64]. In a subanalysis, rescue nitroglycerin and/or PPI use in patients < 30 d before MACE was significantly greater in patients taking clopidogrel and PPI (P < 0.001), suggesting a potential indication bias for PPI use due to misdiagnosed angina, a fact that may have contributed to a confounding bias in previous observational studies[32].

Conducting a post hoc analysis of the randomized Clopidogrel for Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial, Dunn et al[65] reported an increased risk of death, myocardial reinfarction or urgent target vessel revascularization at 28 d for patients using PPIs, independent on the underlying treatment [clopidogrel (OR 1.63, 95% CI: 1.02-2.63) or placebo (OR 1.55, 95% CI: 1.03-2.34)]. Baseline characteristics of the PPI group are not available, but as already discussed by Charlot et al[28], patients under PPI might be sicker than those who are not, explaining the higher rate of adverse cardiovascular events. Another post hoc analysis of a double-blind randomized trial, the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optomizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel (TRITON)-TIMI 38 trial included 13 608 patients with an ACS undergoing PCI and being randomly assigned to prasugrel or clopidogrel. Thirty three percent (4529 patients) were on PPIs at randomisation and exposure during the follow-up was identified by landmark analyses at 3 d, 3 and 6 mo and at the end of follow-up. Baseline characteristics showed that patients treated with PPIs were once again significantly older and had more often pre-existing cardiovascular disease. After multivariable adjustment and propensity score matching, PPI use was not associated with the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or stroke when prescribed with either clopidogrel (HR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.80-1.11) or prasugrel (HR 1.00, 95% CI: 8.84-1.20). Sensitivity analysis of patients being on PPI during the whole follow-up and patients never taking PPIs has not found any increase in adverse cardiovascular events either. Finally, no difference regarding the PPI subtype prescribed was found[26]. Both analyses have the advantage, that each end-point was strictly defined and controlled according to the initial randomized design. However, the analyses weren’t designed to assess PPI use and therefore didn’t randomize PPI treatment, leaving a potential risk of residual confounding even after multivariable adjustment and propensity score analysis. Furthermore, PPI compliance has not been memorized during follow-up- a fact attempt to be adjusted by landmark analyses in the second study.

So far, the only existing randomized controlled double-blind multicenter trial is the Clopidogrel and the Optimization of Gastrointestinal Events (COGENT) trial, including 3878 patients presenting with an ACS or undergoing PCI. Patients were randomized to receive CGT-2168, a fixed combination of 75 mg of clopidogrel and 20 mg of omeprazole vs 75 mg of clopidogrel alone. After a median follow-up of 106 d, a significant reduction in the primary endpoint, a composite of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, was observed in the CGT-2168 group (1.1% vs 2.9%, HR 0.34, 95% CI: 0.18-0.63, P < 0.001). Moreover, analysis of the primary cardiovascular safety end-point, (a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation and ischemic stroke) have not shown any difference between the placebo and omeprazole group (HR with omeprazole 0.99, 95% CI: 0.68-1.44, P = 0.96). Unfortunately, the study was interrupted prematurely due to the bankruptcy of the sponsor, after having included only 3873 of the 5000 initially planned patients. Moreover, wide confidence intervals around the hazard ratio of cardiovascular events and the fact that 94% of the study population was white, do not permit to rule out any significant clinical interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole[25].

The first of three recent meta-analyses was conducted by Kwok et al[36] selecting 23 studies with 93 278 patients. Of note, more than half of the included studies have been available only as abstracts (12 of 23). Studies have been divided into three groups: nonrandomized studies with unadjusted risk ratios, nonrandomized studies with adjusted RR and randomized trials or studies including propensity score matching. Overall analysis of 19 studies reporting the incidence of MACE showed a significantly increased risk in the PPI group (RR 1.43, 95% CI: 1.15-1.77), but data were substantially heterogeneous (I2 = 77%), partially due to considerable variation of the definition of MACE within the studies. Of interest, subanalysis of the propensity matched and randomized trails didn’t show any increased risk (RR 1.15, 95% CI: 0.89-1.48) and data were much less heterogeneous (I2 = 53%). Identical results were found when analysing the risk of myocardial infarction or ACS, leading the authors to conclude that unmeasured confounders may contribute to the results of the lower quality studies[36]. Siller-Matula et al[37] re-analysed 25 studies with 159 138 patients, finding a 29% increase of MACE (RR 1.29, 95% CI: 1.15-1.44) and myocardial infarction (RR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.12-1.53) for concomitant PPI and clopidogrel use. Again heterogeneity in the overall analysis was very important (I2 = 72% vs 77%, respectively) and sensitivity analysis assessing the study quality showed a decreased risk of MACE in high quality studies (RR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.09-1.39) vs low quality studies (RR 1.65, 95% CI: 1.43-1.90), rising again the question of unmeasured confounders and differences in baseline characteristics[37]. Lima et al[38] reviewed 18 studies according to the PRISMA guidelines[66] by classifying them into high (well-performed randomized clinical trials), moderate (post hoc analysis of RCTs and propensity matched studies) and low (observational studies without propensity matching) quality studies. Due to important study heterogeneity, data pooling was a priori not effected. A stratified analysis comparing studies of low (13) with those of moderate quality (5) demonstrated an inverse correlation between clopidogrel-PPI interaction and study quality (P = 0.007), as none of the moderate quality studies reported an association vs 10 in the low quality group[38]. The authors pointed out that according to the large CURE (Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurent Events) trial[67] no or very little advantage in reduction of adverse cardiovascular events when treated with clopidogrel was observed later than 3 mo after an ACS. In contrast to that, in the study of Ho et al[15] the increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events for concomitant PPI and clopidogrel use appears in the long term (not before 180 d), a period when clopidogrel has not been shown to be therapeutically useful any more[38]. Theses results might be explained by unmeasured residual confounders rather than by the existence of a clopidogrel-PPI interaction, a hypothesis endorsed by the three studies having found an elevated risk for adverse cardiovascular events in PPI-users, regardless whether on clopidogrel or not[28,65,68]. Characteristics and results of the cited studies are overviewed in Table 2 by classifying them according to their scientific weight, while Table 3 summarizes the studies reporting on adverse bleeding events.

Table 2.

Overview of important clinical studies on the proton pump inhibitor-clopidogrel interaction

| Study | PPIs used | Procedures to minimize bias | Population | Primary outcome | Results |

| Bhatt et al[25] (randomized, controlled, double-blind trial) | Omeprazole | 3873 patients with ACS or undergoing PCI | Mean 133 d- composite safety endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, coronary revascularisation | No difference between PPI and placebo group (HR with omeprazole 0.99, 95% CI: 0.68-1.44) | |

| O’Donaghue et al[26] (post-hoc analysis of a RCT) | Pantoprazole omeprazole esomeprazole lansoprazole rabeprazole | Propensity score matching; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 13 608 patients undergoing planned PCI for ACS | Composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI or stroke after 6-15 mo | No difference between PPI and clopidogrel alone group (HR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.80-1.11) |

| Dunn et al[65] (post-hoc analysis of a RCT) | Not specified | Multivariable analysis | 2116 patients undergoing PCI | 28 d death, MI, urgent target vessel revas-cularisation 1 yr death, MI or stroke | Increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcome regardless of clopidogrel use (clopidogrel/PPI: OR 1.63, 95% CI: 1.02-2.63 vs placebo/PPI: OR 1.55, 95% CI: 1.03-2.34) |

| Charlot et al[28] (retrospective cohort study) | Esomeprazole pantoprazole lansoprazole omeprazole rabeprazole | Propensity score matching; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 56 406 patients discharged with first-time myocardial infarction | 1 yr composite end point of MI, stroke or cardiovascular death | Increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes in PPI users regardless of clopidogrel use (HR for PPI/clopidogrel: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.22-1.50 vs HR for PPI alone: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.34-1.53) |

| Banerjee et al[32] (retrospective cohort study) | Predominantly omeprazole (88,9%) | Propensity score matching; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 23 200 post PCI patients | 6-yr MACE | No increased risk for MACE in PPI users (HR 0,97, 95% CI: 0.65-1.44) |

| Ray et al[27] (retrospective cohort study) | Pantoprazole lansoprazole esomeprazole omeprazole rabeprazole | Propensity score matching; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 20 596 patients discharged after PCI or ACS | 1 yr composite end point of ACS, stroke or cardiovascular death | No increased risk for serious cardiovascular disease in PPI users (HR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.82-1.19) |

| Rassen et al[31] (retrospective cohort study) | Pantoprazole omeprazole rabeprazole lansoprazole esomeprazole | Propensity score matching; | 18 565 patients discharged after PCI or ACS (age > 65 yr) | 180 d composite end point of hospitalization for MI and PCI or death of any cause | Trend towards a higher risk of composite end point in PPI users (RR 1.26, 95% CI: 0.97-1.63) |

| Simon et al[30] (retrospective cohort study) | Omeprazole esomeprazole pantoprazole lansoprazole | Propensity score matching; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 2744 clopidogrel and PPI-naive patients with definite MI | In hospital and 1-yr death, reinfarction or stroke | No increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in PPI users (HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.90-1.08) |

| Harjai et al[29] (retrospective cohort study) | Omeprazole esomeprazole | Propensity score matching; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 2651 patients discharged after PCI for stable and unstable CAD | 6-mo MACE | No increased risk for MACE in PPI users (HR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.63-1.27) |

| van Boxel et al[14] (retrospective cohort study) | Pantoprazole omeprazole rabeprazole lansoprazole | Multivariable analysis | 18 139 clopidogrel users | 2 yr composite endpoint of ACS, stroke and any cause death | Increased risk of composite endpoint (HR 1.75, 95% CI: 1.58-1.94), myocardial infarction (HR 1.93, 95% CI: 1.40-2.65) and unstable angina pectoris (HR 1.79, 95% CI: 1.60-2.03) |

| Juurlink et al[16] (population-based nested case-control study) | Omeprazole rabeprazole lansoprazole pantoprazole | Nested case –control; multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 13 636 patients discharged after ACS (age > 65 yr) | 90-d readmission for acute MI | Increased risk of reinfarction (OR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.03-1.57) in PPI users except pantoprazole |

| Ho et al[15] (retrospective cohort study) | Omeprazole rabeprazole lansoprazole pantoprazole | Multivariable and sensitivity analysis | 8205 patients discharged after ACS | 3 yr death or rehospitalization for ACS | Increased risk for death or rehospitalization in PPI users (OR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.11-1.41) |

ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; MI: Myocardial infaction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; RR: Relative risk; HR: Hazard ratio; MACE: Major adverse cardiovascular event; RCT: Randomized controlled trial.

Table 3.

Summary of studies reporting on adverse bleeding events

| Study | Observed adverse event | Ascertainment | Results |

| Bhatt et al[25] | Composite of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (of known and unknown origin): overt bleeding, ulcers, symptomatic erosions, obstruction, perforation or decrease in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL | Endoscopic and radiologic confirmation (in known origin subgroup) | Significative reduction of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the omeprazole treated group (1.1% against 2.9% under placebo; HR 0.34, 95% CI: 0.18-0.63) |

| Ray et al[27] | Hospitalization for bleeding at a gastroduodenal site (excluding angiodysplasia) or other gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal sites | Validated diagnostic codes with PPV of 91% | Adjusted 50% reduction of hospitalization in the PPI treated group (HR 0.50, 95% CI: 0.39-0.65), no significant difference concerning bleeding at other sites |

| van Boxel et al[14] | Occurence of complicated or non complicated peptic ulcer disease | ICD-9 diagnostic codes | Low incidence (0.7% with PPI against 0.2%) but significant increase of peptic ulcer disease in the PPI treated group even after multivariable adjusting (HR 4.76, 95% CI: 1.18-19.17) |

| Charlot et al[28] | Hospitalization for gastrointestinal bleeding | ICD-9 diagnostic codes | No reduction between the clopidogrel with PPI and clopidogrel alone group |

| Harjai et al[29] | TIMI major bleeding: intracranial hemorrage or a ≥ 5 g/dL decrease in hemoglobine TIMI minor bleeding: observed blood loss with decrease ≥ 3 g/dL in hemoglobine | Guthrie Health System database | No significant difference between the clopidogrel with PPI and clopidogrel alone group |

| Simon et al[30] | In-hospital major bleeding (not specified) or need for blood transfusion | FAST-MI registry | No significant difference between the clopidogrel with PPI and clopidogrel alone group |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; PPV: Positive predictive value; PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; ICD-9: International classification of disease-9th revision; FAST-MI: French registry of acute-ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

To summarize, pharmacodynamic studies suggest an existing interaction between clopidogrel and omeprazole but not with pantoprazole, a phenomenon that may be explained by the higher inhibitory potency of omeprazole for the cytochrome P450 CYP2C19[54], a key enzyme in the metabolic activation of clopidogrel[39].

Nevertheless, the clinical impact of this biochemical interaction still remains unclear, as several cohort studies report an interaction and consecutive increase in adverse cardiovascular events for omeprazole[14-22]. In contrast to that, recent retrospective studies including propensity score matching in order to minimise underlying bias have not show any clopidogrel-PPI interaction[27-35] (except one recent study using a larger endpoint including overall death, myocardial infarction, stroke and critical limb ischemia[69]). In addition to that, post-hoc analyses of randomized trials[26,65] and the only randomized double blinded trial available so far have not found any increase in adverse cardiovascular events for the PPI treated group[25]. Finally, several meta-analyses pointed out that there was an inverse correlation between study quality and a reported statistically positive interaction[36-38]. Despite of that, the United states Food and Drug Administration and the European Medecines Agency still discourage the use of PPI (especially omeprazole) concomitantly with clopidogrel[23,24].

Three recommendations to health care providers could therefore be made for the moment: (1) A gastrointestinal risk evaluation (e.g., history of gastrointestinal bleeding, dyspepsia, therapeutic anticoagulation, concomitant NSAIDS use especially in elderly persons and in the presence of helicobacter pylori[70-73]) has to be performed in each patient, as clopidogrel treatment and dual antiplatelet therapy rise the risk of adverse gastrointestinal events and mortality[3,4,25,74,75]. Patients at high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding should have prescribed concomitant PPIs when under clopidogrel, due to the high mortality rate in case of bleeding[2]; (2) Favoring pantoprazole over omeprazole pharmacologically leads to less inhibition of the CYP2C19 isoenzyme, but the clinical impact of this pharmacologic difference has not been proved so far. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no clinical trial (regardless of its quality) has ever demonstrated a clear interaction for pantoprazole, making it a rather safe choice, especially regarding recent moderate and high quality publications. Furthermore the standard daily dose of 40 mg doesn’t seem to induce any significant pharmacodynamic interaction with clopidogrel, as none was found for a 80 mg/d dose[12,57]; and (3) Widening the delay between clopidogrel and PPI intake by a minimum of 12 h (a concept based on the rapid metabolization of clopidogrel[49] ), doesn’t seem to avoid the possible drug interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs[12,56,57].

In conclusion, rising evidence accumulates to infirm an interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel. This point suggests that the bleeding reduction benefit overweighs the possible adverse cardiovascular risk in patients with an indication for PPI treatment taking dual antiplatelet treatment. Of course, adequate powered randomized controlled trials with pharmacodynamic assessment are still needed to infirm the persisting doubt upon the PPI-clopidogrel interaction.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Vittorio Ricci, Professor, Physiology, Human Physiology Section, University of Pavia Medical School, Human Physiology Sect Via Forlanini 6, 27100 Pavia, Italy; Richard Hu, Gastroenterology, Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, 14445 Olive View Drive, Los Angeles, CA 91342, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, King SB, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE, et al. 2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120:2271–2306. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, Bhatt DL, Bjorkman DJ, Clark CB, Furberg CD, Johnson DA, Kahi CJ, Laine L, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2533–2549. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwok CS, Nijjar RS, Loke YK. Effects of proton pump inhibitors on adverse gastrointestinal events in patients receiving clopidogrel: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2011;34:47–57. doi: 10.2165/11584750-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan FK, Ching JY, Hung LC, Wong VW, Leung VK, Kung NN, Hui AJ, Wu JC, Leung WK, Lee VW, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to prevent recurrent ulcer bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:238–244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abraham NS. Prescribing proton pump inhibitor and clopidogrel together: current state of recommendations. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:558–564. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834a382e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Le Gal G, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazol on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2508–2509. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, Mansourati J, Mottier D, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siller-Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM, Kreiner G, Christ G, Jilma B. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Am Heart J. 2009;157:148.e1–148.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernando H, Bassler N, Habersberger J, Sheffield LJ, Sharma R, Dart AM, Peter KH, Shaw JA. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study to determine the effects of esomeprazole on inhibition of platelet function by clopidogrel. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1582–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontes-Carvalho R, Albuquerque A, Araújo C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Ribeiro VG. Omeprazole, but not pantoprazole, reduces the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel: a randomized clinical crossover trial in patients after myocardial infarction evaluating the clopidogrel-PPIs drug interaction. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:396–404. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283460110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J, Poyet R, Gaborit B, Bali L, Brissy O, Morange PE, Alessi MC, Bonnet JL. Comparison of omeprazole and pantoprazole influence on a high 150-mg clopidogrel maintenance dose the PACA (Proton Pump Inhibitors And Clopidogrel Association) prospective randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angiolillo DJ, Gibson CM, Cheng S, Ollier C, Nicolas O, Bergougnan L, Perrin L, LaCreta FP, Hurbin F, Dubar M. Differential effects of omeprazole and pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel in healthy subjects: randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover comparison studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:65–74. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neubauer H, Engelhardt A, Krüger JC, Lask S, Börgel J, Mügge A, Endres HG. Pantoprazole does not influence the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel-a whole blood aggregometry study after coronary stenting. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010;56:91–97. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e19739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Boxel OS, van Oijen MG, Hagenaars MP, Smout AJ, Siersema PD. Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal outcomes in clopidogrel users on proton pump inhibitors: results of a large Dutch cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2430–2436; quiz 2437. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, Rumsfeld JS. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301:937–944. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, Szmitko PE, Austin PC, Tu JV, Henry DA, Kopp A, Mamdani MM. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180:713–718. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreutz RP, Stanek EJ, Aubert R, Yao J, Breall JA, Desta Z, Skaar TC, Teagarden JR, Frueh FW, Epstein RS, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on the effectiveness of clopidogrel after coronary stent placement: the clopidogrel Medco outcomes study. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:787–796. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta E, Bansal D, Sotos J, Olden K. Risk of adverse clinical outcomes with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following percutaneous coronary intervention. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1964–1968. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pezalla E, Day D, Pulliadath I. Initial assessment of clinical impact of a drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1038–1039; author reply 1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockl KM, Le L, Zakharyan A, Harada AS, Solow BK, Addiego JE, Ramsey S. Risk of rehospitalization for patients using clopidogrel with a proton pump inhibitor. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:704–710. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaglia MA, Torguson R, Hanna N, Gonzalez MA, Collins SD, Syed AI, Ben-Dor I, Maluenda G, Delhaye C, Wakabayashi K, et al. Relation of proton pump inhibitor use after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents to outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evanchan J, Donnally MR, Binkley P, Mazzaferri E. Recurrence of acute myocardial infarction in patients discharged on clopidogrel and a proton pump inhibitor after stent placement for acute myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:168–171. doi: 10.1002/clc.20721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United states Food and Drug Administration. Information for Heallthcare Professionals: Update to the labeling of Clopidogrel Bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) to alert healthcare professionales about drug intercation with omeprazole (marketed as Prilosec and Prilosec OTC) Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHealthcareProfessionals/ucm0190787.htm.

- 24.European Medecines Agency. Public Statement on Possible Interaction Between Clopidogrel and Proton-Pump Inhibitors (online alert) Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/Plavix/32895609en.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2011.

- 25.Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, Cohen M, Lanas A, Schnitzer TJ, Shook TL, Lapuerta P, Goldsmith MA, Laine L, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, Michelson AD, Hautvast RW, Ver Lee PN, Close SL, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, Chung CP, Smalley WE, Hall K, Daugherty JR, Kaltenbach LA, Stein CM. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:337–345. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlot M, Ahlehoff O, Norgaard ML, Jørgensen CH, Sørensen R, Abildstrøm SZ, Hansen PR, Madsen JK, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Proton-pump inhibitors are associated with increased cardiovascular risk independent of clopidogrel use: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:378–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-6-201009210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harjai KJ, Shenoy C, Orshaw P, Usmani S, Boura J, Mehta RH. Clinical outcomes in patients with the concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Guthrie Health Off-Label Stent (GHOST) investigators. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:162–170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.958884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon T, Steg PG, Gilard M, Blanchard D, Bonello L, Hanssen M, Lardoux H, Coste P, Lefèvre T, Drouet E, et al. Clinical events as a function of proton pump inhibitor use, clopidogrel use, and cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype in a large nationwide cohort of acute myocardial infarction: results from the French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) registry. Circulation. 2011;123:474–482. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.965640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rassen JA, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S. Cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients using clopidogrel with proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention or acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:2322–2329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banerjee S, Weideman RA, Weideman MW, Little BB, Kelly KC, Gunter JT, Tortorice KL, Shank M, Cryer B, Reilly RF, et al. Effect of concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaspar A, Ribeiro S, Nabais S, Rocha S, Azevedo P, Pereira MA, Brandāo A, Salgado A, Correia A. Proton pump inhibitors in patients treated with aspirin and clopidogrel after acute coronary syndrome. Rev Port Cardiol. 2010;29:1511–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zairis MN, Tsiaousis GZ, Patsourakos NG, Georgilas AT, Kontos CF, Adamopoulou EN, Vogiatzidis K, Argyrakis SK, Fakiolas CN, Foussas SG. The impact of treatment with omeprazole on the effectiveness of clopidogrel drug therapy during the first year after successful coronary stenting. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:e54–e57. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossini R, Capodanno D, Musumeci G, Lettieri C, Lortkipanidze N, Romano M, Nijaradze T, Tarantini G, Cicorella N, Sirbu V, et al. Safety of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22:199–205. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328343b03a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwok CS, Loke YK. Meta-analysis: the effects of proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular events and mortality in patients receiving clopidogrel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:810–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siller-Matula JM, Jilma B, Schrör K, Christ G, Huber K. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcome in patients treated with clopidogrel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2624–2641. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima JP, Brophy JM. The potential interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2010;8:81. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazui M, Nishiya Y, Ishizuka T, Hagihara K, Farid NA, Okazaki O, Ikeda T, Kurihara A. Identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the two oxidative steps in the bioactivation of clopidogrel to its pharmacologically active metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:92–99. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias W, Braunwald E, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Walker JR, Simon T, Antman EM, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Genetic variants in ABCB1 and CYP2C19 and cardiovascular outcomes after treatment with clopidogrel and prasugrel in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial: a pharmacogenetic analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1312–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61273-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hulot JS, Collet JP, Silvain J, Pena A, Bellemain-Appaix A, Barthélémy O, Cayla G, Beygui F, Montalescot G. Cardiovascular risk in clopidogrel-treated patients according to cytochrome P450 2C19*2 loss-of-function allele or proton pump inhibitor coadministration: a systematic meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mega JL, Simon T, Collet JP, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bliden K, Cannon CP, Danchin N, Giusti B, Gurbel P, et al. Reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes among patients treated with clopidogrel predominantly for PCI: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:1821–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Méneveau N, Steg PG, Ferrières J, Danchin N, Becquemont L. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:363–375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernando H, Dart AM, Peter K, Shaw JA. Proton pump inhibitors, genetic polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel therapy. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:933–944. doi: 10.1160/TH10-11-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunfeld NG, Mathot RA, Touw DJ, van Schaik RH, Mulder PG, Franck PF, Kuipers EJ, Geus WP. Effect of CYP2C19*2 and *17 mutations on pharmacodynamics and kinetics of proton pump inhibitors in Caucasians. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:752–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang CC, Chen YC, Leu HB, Chen TJ, Lin SJ, Chan WL, Chen JW. Risk of adverse outcomes in Taiwan associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors in patients who received percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1705–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin SL, Chang HM, Liu CP, Chou LP, Chan JW. Clinical evidence of interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. World J Cardiol. 2011;3:153–164. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v3.i5.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lettino M. Inhibition of the antithrombotic effects of clopidogrel by proton pump inhibitors: facts or fancies? Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tantry US, Kereiakes DJ, Gurbel PA. Clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors: influence of pharmacological interactions on clinical outcomes and mechanistic explanations. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:365–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi S, Klotz U. Proton pump inhibitors: an update of their clinical use and pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:935–951. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ogawa R, Echizen H. Drug-drug interaction profiles of proton pump inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:509–533. doi: 10.2165/11531320-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sachs G, Shin JM, Howden CW. Review article: the clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23 Suppl 2:2–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlström M, Weidolf L. Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:821–827. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fock KM, Ang TL, Bee LC, Lee EJ. Proton pump inhibitors: do differences in pharmacokinetics translate into differences in clinical outcomes? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:1–6. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferreiro JL, Ueno M, Capodanno D, Desai B, Dharmashankar K, Darlington A, Charlton RK, Bass TA, Angiolillo DJ. Pharmacodynamic effects of concomitant versus staggered clopidogrel and omeprazole intake: results of a prospective randomized crossover study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:436–441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.957829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferreiro JL, Ueno M, Tomasello SD, Capodanno D, Desai B, Dharmashankar K, Seecheran N, Kodali MK, Darlington A, Pham JP, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of pantoprazole therapy on clopidogrel effects: results of a prospective, randomized, crossover study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:273–279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.960997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stürmer T, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Adjusting effect estimates for unmeasured confounding with validation data using propensity score calibration. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:279–289. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The bias due to incomplete matching. Biometrics. 1985;41:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Stürmer T. Indications for propensity scores and review of their use in pharmacoepidemiology. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stürmer T, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Performance of propensity score calibration--a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1110–1118. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Rothman KJ, Setoguchi S, Schneeweiss S. Applying propensity scores estimated in a full cohort to adjust for confounding in subgroup analyses. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1002/pds.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mogun H, Brookhart MA. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology. 2009;20:512–522. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dunn SP, Macaulay TE, Brennan DM, Campbell CL, Charnigo RJ, Smyth SS, Berger PB, Steinhubl SR, Topol EJ. Baseline proton pump inhibitor use is associated with increased cardiovascular events with and without the use of clopidogrel in the CREDO trial. Circulation. 2008;118:S_815. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmidt M, Johansen MB, Robertson DJ, Maeng M, Kaltoft A, Jensen LO, Tilsted HH, Bøtker HE, Sørensen HT, Baron JA. Concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors is not associated with major adverse cardiovascular events following coronary stent implantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muñoz-Torrero JF, Escudero D, Suárez C, Sanclemente C, Pascual MT, Zamorano J, Trujillo-Santos J, Monreal M. Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel in patients with coronary, cerebrovascular, or peripheral artery disease in the factores de Riesgo y ENfermedad Arterial (FRENA) registry. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;57:13–19. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181fc65e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2093–2099. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lanas A, Serrano P, Bajador E, Fuentes J, Sáinz R. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with non-aspirin cardiovascular drugs, analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:173–178. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abraham NS, Hartman C, Castillo D, Richardson P, Smalley W. Effectiveness of national provider prescription of PPI gastroprotection among elderly NSAID users. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lanas A, Fuentes J, Benito R, Serrano P, Bajador E, Sáinz R. Helicobacter pylori increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking low-dose aspirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:779–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Straube S, Tramèr MR, Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Mortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: effects of time and NSAID use. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McQuaid KR, Laine L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adverse events of low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel in randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2006;119:624–638. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]