Abstract

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are specialized type I IFN producers, which play an important role in pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders. Dysregulated autoreactive B cell activation is a hallmark in most autoimmune diseases. This study was undertaken to investigate interactions between pDCs and autoreactive B cells. After co-culture of autoreactive B cells that recognize self-Ag small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles with activated pDCs, we found that pDCs significantly enhance autoreactive B cell proliferation, autoAb production, and survival in response to toll-like receptor (TLR) and BCR stimulation. Neutralization of IFN-α/β and IL-6 abrogated partially pDC-mediated enhancement of autoreactive B cell activation. Transwell studies demonstrated that pDCs could provide activation signals to autoreactive B cells via cell-to-cell contact manner. The involvement of the ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway was revealed as contributing to this effect. This in vitro enhancement effect was further demonstrated by an in vivo B cell adoptive transfer experiment, which showed that autoreactive B cell proliferation and activation were significantly decreased in MyD-88-deficient mice compared to WT mice. These data suggest the dynamic interplay between pDCs and B cells is required for full activation of autoreactive B cells upon TLR or BCR stimulation.

Introduction

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are a major source of type I IFNs in the blood, representing 0.2% to 0.8% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in both humans and mice (1). Previous studies demonstrated that pDCs play a critical role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Although absolute numbers of pDCs are decreased in the circulation of SLE patients, large numbers of activated pDCs are found in skin lesions and actively produce type I IFNs in these patients (2, 3). The pDCs appear to be activated by DNA-containing immune complexes from the patient serum in a toll-like receptor (TLR)9- and CD32-dependent manner (4). U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle (snRNP) immune complexes found in SLE patients also trigger IL-6 and IFN-α production in pDCs via a TLR7-dependent mechanism (5). Even the U1 snRNP itself can directly stimulate pDCs for IFN-α production (6). The elevated IFN-α levels in serum and induction of IFN-regulated genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in lupus patients have been shown to correlate with disease activity and severity (7–9) (10, 11). In addition, mouse models of lupus in which the IFN receptor (IFNR) is deleted fail to develop disease manifestations (12), suggesting the crucial role of IFN-α in lupus pathogenesis.

pDCs also regulate B cells to differentiate into plasma cells for Ab production via type I IFNs and IL-6 (13, 14). Type I IFNs stimulate B cells to generate non-immunoglobulin (Ig)-secreting plasma blasts while IL-6 promotes their further differentiation into Ab-secreting plasma cells. Type I IFNs can also directly stimulate B cells for Ab production via IFNR (15), enhance Ab secretion in vivo (16) and trigger isotype switching by inducing myeloid DCs (mDCs) to upregulate the expression of B-lymphocyte stimulator (Blys) or B cell activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), two potent B cell activating molecules (17). In addition, type I IFNs control B cell TLR sensitivity such as TLR7 to trigger B cell expansion and differentiation toward Ab-secreting plasma cells (18). A recent study also indicates that pDCs synergistically upregulate costimulatory molecule CD86 expression, cytokine secretion, and plasma cell differentiation of human B cells stimulated with TLR ligand CpG-C or BCR crosslinking (14). These studies have underscored a pivotal role of pDCs in B cell activation and differentiation, mainly via soluble mediators. However, little is known about the role of pDCs in the regulation of autoreactive B cells. Dysregulated autoreactive B cells are one of the hallmarks in many autoimmune diseases.

In this study, we hypothesized that pDCs regulate autoreactive B cell activation for pathogenic autoAb production. The anti-snRNP Ig heavy chain transgenic (Tg) mouse model was used to explore the possible interplay between pDCs and autoreactive anti-snRNP B cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that anti-snRNP B cells constitute the normal B cell repertoire and that the frequency of these B cells ranges from 15 to 35% in normal background mice (19). The anti-snRNP B cells of normal background mice do not produce autoAb but can be activated by stimulation such as through TLR engagement or T cell help (19, 20). Here, we demonstrate that activated pDCs trigger anti-snRNP B cells for enhanced proliferation, autoAb production, and survival in response to TLR stimulation or BCR ligation. These effects are not only mediated by cytokines released by pDCs but are also dependent on cell-to-cell contact. Thus, pDCs provide helper signals to trigger autoreactive B cell activation that involves autoimmune pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

B10.A or C57Bl/6 anti-snRNP (2-12H) Tg mice were generated as previously described (19). CD40L-deficient (CD40L−/−) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MyD88−/− mice were obtained from Osaka University (Osaka, Japan). All mice were housed and bred in a conventional facility at the University of Louisville (Louisville, KY). Animal care and experiments were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Louisville.

Bone marrow-derived pDCs

BM cells from naïve B10.A mice were isolated by flushing femurs and tibiae with DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The cells were then passed through a 70-μm cell strainer. After lysis of red blood cells, the cells were centrifuged and re-suspended at 106 cells/ml in DMEM medium in the presence of Flt3-ligand (200 ng/ml, generously provided by Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) as described previously (21, 22). Cultures were incubated at 37°C was in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Every 4 days of culture, half of the medium removed and fresh cytokine-supplemented culture medium was added back into cultures. After 7–8 days of culture, cells were collected and labeled with anti-mouse B220 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) and separated using autoMACS. The purity of pDCs (CD11cint, B220+, mPDCA-1+) was >90% as assessed by flow cytometry. To fix pDCs, freshly isolated or CpG (1826, Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) or Gardiquimod (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) stimulated pDCs were mixed with paraformaldehyde (1% in PBS) for 4 min at 4°C and then extensively washed.

Autoreactive B cell purification and co-culture of B cells and pDCs

B cells were purified from 2-12H Tg mice using negative selection by magnetic bead technology. In brief, lymphocytes from splenocytes were enriched by Ficoll-Hypaque density separation. Cells were labeled with anti-mouse CD43 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech) and separated using autoMACS. The purity of B cells was >95% as assessed by flow cytometry. Co-culture of B cells and pDCs were performed in RPMI1640 medium (Caisson Laboratories, Rexbury, ID), supplemented with 10% inactivated FBS, 10−3 M sodium pyruvate, 2×10−3 M glutamine, and 50 μM 2-ME. B cells (1×105/well, 96-well plate) were stimulated with varying amounts of CpG, Gardiquimod or anti-mouse IgM F(ab')2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in the presence or absence of pDCs. B cell proliferation was determined by [3H]-TdR incorporation after 48 h of coculture. Cells were incubated for the last 6 h with 1 μCi of [3H]-TdR. Sample wells were harvested onto filters and incorporated radioactivity was counted in a Betaplate liquid scintillation counter (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, CT). Experiments were conducted in triplicate and results were expressed as cpm ± SEM. In some experiments, recombinant mouse IFN-α (PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ) or recombinant IL-6, recombinant mouse TACI (transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor)/Fc chimera fusion protein, neutralizing anti-mouse IFN-α/β R2 Ab, anti-mouse IL-6 Ab (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-mouse ICAM-1 mAb (clone: YNI.7.4, BioExpress, West Lebanon, NH), anti-mouse LFA-1 Ab (clone: M17/4, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and corresponding isotype Abs were added during the culture.

B cell survival assay

Purified B cells were stimulated with or without CpG or Gardiquimod in the presence or absence of pDCs for the indicated time and stained with Annexin V PE Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSClibur, BD Immunocytometry System, San Jose, CA).

Transwell Study

B cells and pDCs were cultured in the separated compartments using a transwell system (0.4 μm, Costar, Wilmington, MA). Cultures were performed in 24-well plate in a total volume of 0.7 ml. B cells (5×105 /well) were cultured in the lower compartment and pDCs (1.25×105) were cultured in the upper compartment of the transwells. B cell proliferation was assayed by transferring cells in lower chambers into 96-well plates after 2-day culture and pulsing them with [3H]-TdR for another 6 h of culture.

Total IgM and anti-snRNP Ab detection

Total IgM levels were determined using mouse IgM ELISA Kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX). Detection of anti-snRNP Ab by ELISA was performed as previously described (23). Briefly, culture supernatant (5 days culture) or serial diluted mouse sera were added to plates coated with recombinant snRNP. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) was used as a secondary Ab. Assays were developed with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) conductivity substrate (BioFX Laboratories, Inc., Owings Mills, MD) and the OD value was measured at 450 nm. In some experiments, ABTS 1 component substrate was used and the OD 405 nm was measured.

In vivo anti-ICAM-1 mAb blocking assay and B cell proliferation assay

For in vivo anti-ICAM-1 mAb blocking assay, anti-snRNP Tg mice were received blocking anti-ICAM-1 mAb 500 μg by i.p. injection at day −3, 250 μg at days −1, 1, and 3, respectively. Isotype mAb was used as control. All mice were immunized i.v. with CpG (100 μg per mouse) on days 1 and 4. The sera were collected on day 7 for anti-snRNP Ab measurement. For in vivo B cell proliferation assay, B cells purified from splenocytes of C57Bl/6 2-12H Tg mice were labeled with 5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) for 10 min at 37°C. B cells (1×107 per mouse) were then adoptively transferred into C57Bl/6 mice or MyD88−/− mice. Recipient mice were immunized intravenously with or without CpG (100 μg per mouse) on days 1 and 4. The sera were collected on day 7 for anti-snRNP Ab measurement. Splenic cells were collected and stained with mAbs for flow cytometry analysis.

Flow cytometry

Cells were blocked in the presence of anti-CD16/CD32 at 4°C for 15 min before staining. All mAbs were purchased from eBioscience or BD-PharMingen (San Jose, CA). In addition to isotype controls, the following mAbs were used: anti-CD11c-FITC, anti-CD27-FITC, anti-mPDCA-1-PE, anti-CD86-PE, anti-CD40-PE, anti-CD40L-FITC, anti-CD80-PE, anti-CD83-PE, anti-CD70-PE, anti-CD138-PE, anti-ICAM-PE, anti-CD19-APC, and anti-CD45R/B220-APC. Cells were incubated with conjugated mAbs at 4°C for 30 min, washed twice with PBS/2%FCS. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with BD FACSCalibur cytometer and data were analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Immunofluorescence staining

Fresh spleen tissues were embedded in OCT medium (Tissue-Tek® OCT compound 4853, Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) by using dry ice-cooled isopentane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) bath. Cryosections (7 μm) were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 15 min and air-dried at room temperature. Sections were blocked with 20% FBS in PBS for 30 min and then were stained with the following primary Abs at 4°C overnight: APC rat-anti mouse CD4 (1:50 dilution, Clone RM4-5, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), biotinylated rat-anti mouse PDCA-1 (1:10 dilution, Clone JF05-1C2.4.1, Miltenyi Biotec). After three washes with PBS, sections were incubated with steptavidin-Alexa 594 (1:150 dilution, Molecular Probes, Invitorgen, Carlsbad, CA) for 45 min. Slides were mounted with the anti-fade fluorescence-mounting medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Images were acquired by Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope system with HC PL APO 20x/0,7 CS (air) objective (Leica Microsystems Inc., Exton, PA).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean values ± SEM. Statistical significance of difference was determined by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s T-test. Differences were considered significant for p <0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 4.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

pDCs enhance anti-snRNP B cell proliferation upon TLR stimulation or BCR engagement

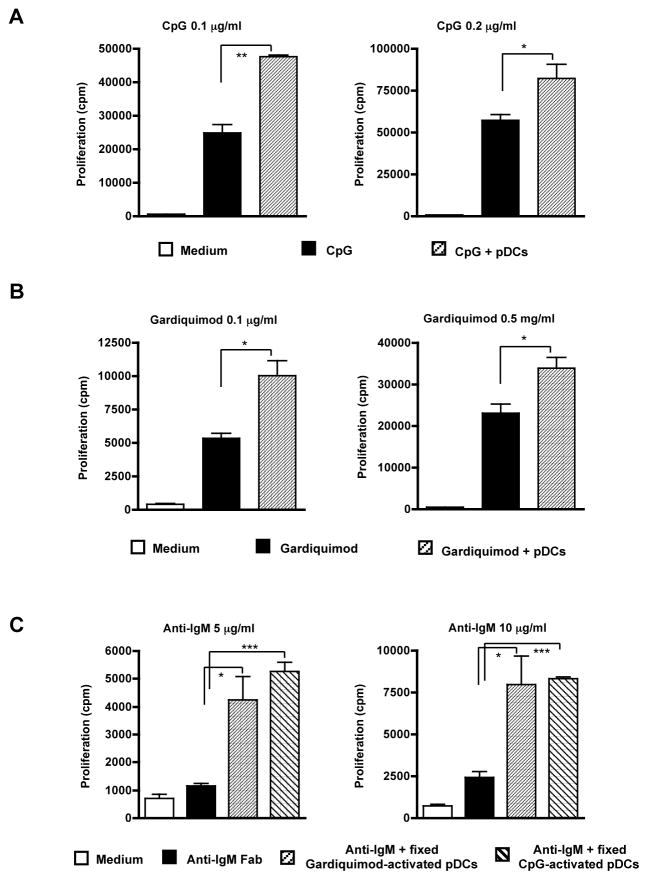

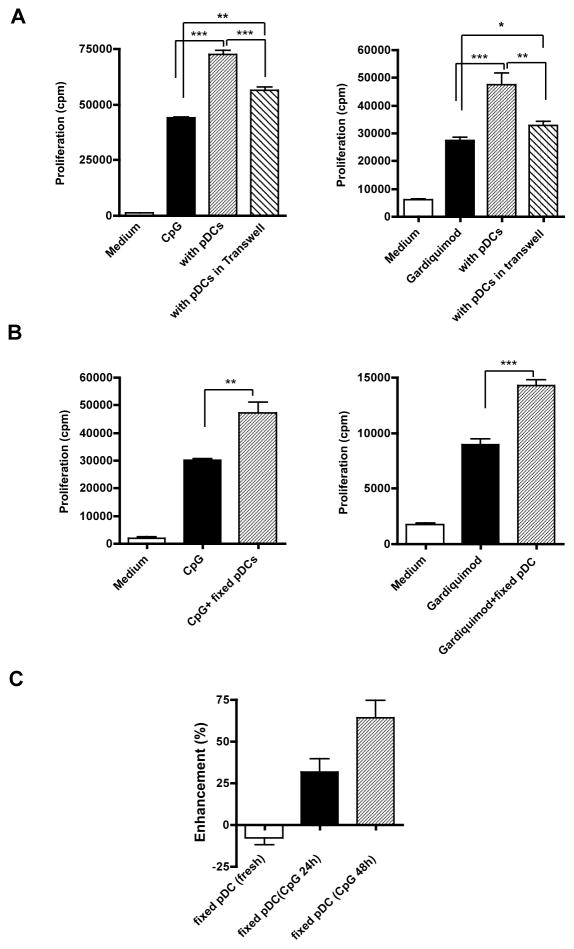

DCs derived from murine bone marrow cells by co-culture with Flt3-ligand contain the CD11cintB220+mPDCA-1+ pDCs and conventional CD11chighB220− DCs. The pDCs secreted large amounts of TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-α upon CpG stimulation (data not shown). To examine whether pDCs induce autoreactive B cell activation, purified anti-snRNP B cells were co-cultured with pDCs in the presence of different stimuli. Autoreactive anti-snRNP Tg B cell proliferation in response to CpG stimulation was significantly enhanced in the presence of pDCs (Fig. 1A). This enhancement is proportional to the numbers of pDCs added in the culture (data not shown). Similarly, autoreactive B cell proliferation in response to TLR7 ligand Gardiquimod was also significantly increased in the presence of pDCs (Fig. 1B). To explore whether BCR crosslinking-induced B cell proliferation is influenced by pDCs, anti-snRNP B cells were stimulated with anti-IgM Ab in the presence or absence of pDCs. pDCs were pre-activated with TLR7 or TLR9 ligand and then fixed to eliminate any cytokine release that could impact B cell proliferation. Autoreactive B cells had a low proliferative response upon BCR ligation. However, activated pDCs significantly augment BCR-induced B cell proliferation (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the presence of pDCs can significantly enhance anti-snRNP autoreactive B cell proliferation in response to both TLR stimulation and BCR ligation.

Figure 1.

pDCs enhance autoreactive B cell proliferation in response to TLR stimulation and BCR ligation. Purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (1×105/well) were cultured for 48 h with the indicated concentrations of CpG (A) or Gardiquimod (B) with or without pDCs (0.25 ×105/well) at a ration of 4:1. pDCs alone with stimuli were used as controls. All cultures were then pulsed with [3H]-TdR for the last 6 h. Cpm counts from pDCs alone were subtracted from those of pDC-B cell co-cultures. (C) B cell proliferation stimulated with varying concentrations of anti-IgM for 48 h in the presence of fixed Gardiquimod or CpG-activated pDCs. Freshly isolated pDCs were used as control. Each bar represents the mean and error bars indicate SEM. Data are representative of five independent experiments. * p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

pDCs induce autoreactive anti-snRNP B cells to differentiate into plasma cells and secrete anti-snRNP autoAb

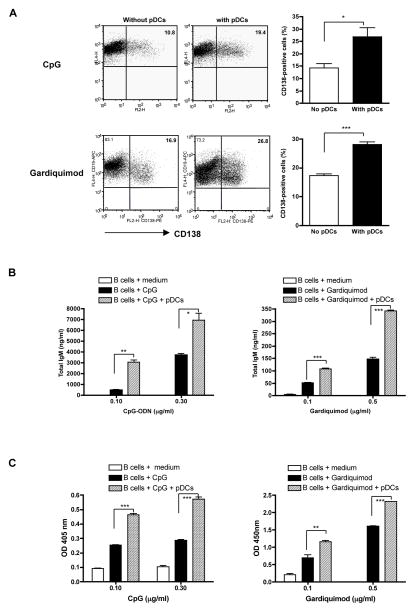

Given the role of pDCs in inducing normal B cell differentiation, we examined whether pDCs would enhance autoreactive B cell differentiation. CD138 (syndecan-1) is a plasma cell marker expressed at various levels on different developmental stages of plasma cells (24). In the presence of pDCs, the CD138+ plasma cells were significantly increased upon CpG or Gardiquimod stimulation (Fig. 2A). The total IgM levels were also augmented when B cells were co-cultured with pDCs (Fig. 2B). In addition, anti-snRNP autoAb production was enhanced by the addition of pDCs (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that pDCs indeed provide help signals for autoreactive B cell differentiation to plasma cells and subsequently for autoAb production.

Figure 2.

CD138 plasma cell differentiation and total IgM and anti-snRNP autoAb production. A, CD138 expression on autoreactive B cells upon TLR stimulation in the presence of pDCs (n=3). Purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells were stimulated with CpG (0.1 μg/ml) or Gardiquimod (0.5 μg/ml) for 72 h with or without pDCs (4:1 ratio). Cells were harvested and stained with CD19 and CD138 mAbs and the percentage of CD138 positive cells was determined. Cells were gated on CD19+ B cell population. B and C, Anti-snRNP Tg B cells (5×105/well) were stimulated with indicated concentration of CpG or Gardiquimod for 5 days with or without pDCs. The culture supernatants were assayed for total IgM (B) or anti-snRNP autoAb production (C) by ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. * p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

pDCs promote autoreactive B cell survival in response to TLR stimulation

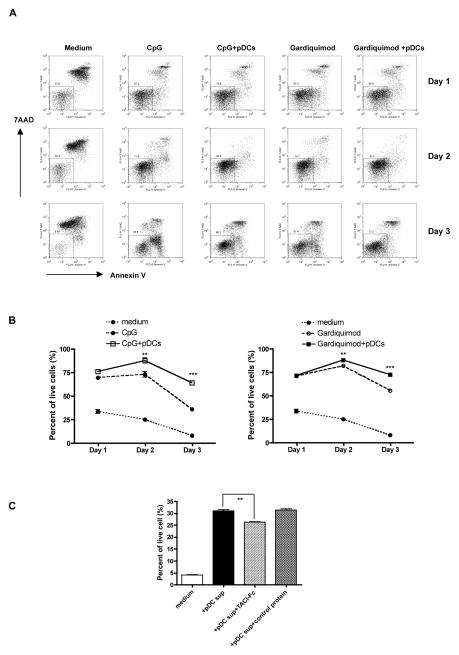

It has been shown that macrophage or DC-mediated human B cell regulation depends on the TNF family ligand BLys/BAFF and APRIL (17, 25). Engagement of BLys (BAFF) and/or APRIL with corresponding receptors expressed on B cells leads to enhanced B cell survival via upregulation of the antiapoptotic molecules NF-kB and Bcl-2 (26). To determine whether autoreactive B cell survival could be enhanced by activated pDCs, anti-snRNP B cells were co-cultured with activated pDCs. As shown in Figs 3A and 3B, autoreactive B cell survival was significantly enhanced from day 2 when activated pDCs were present. Further studies demonstrated that TACI/Fc fusion protein significantly decreased activated pDC-mediated enhancement of B cell survival (Fig. 3C), suggesting that BLys and its receptor play a critical role in this effect.

Figure 3.

Enhanced B cell survival in the presence of pDCs. Purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells were cultured in the presence or absence of CpG (0.1 μg/ml) or Gardiquimod (0.5 μg/ml) with or without pDCs. B cell survival was evaluated by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining. Representative dot plots (A) and the percentage of live cells are shown (n=4, B). C, Anti-snRNP B cells were incubated with TACI/Fc fusion protein or control protein (100 ng/ml) for 20 min and then stimulated with CpG-activated pDC supernatants for 3 days. B cell survival was assessed by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining (n=3). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Enhanced autoreactive B cell proliferation and autoAb production in the presence of pDCs are partially mediated by soluble cytokines

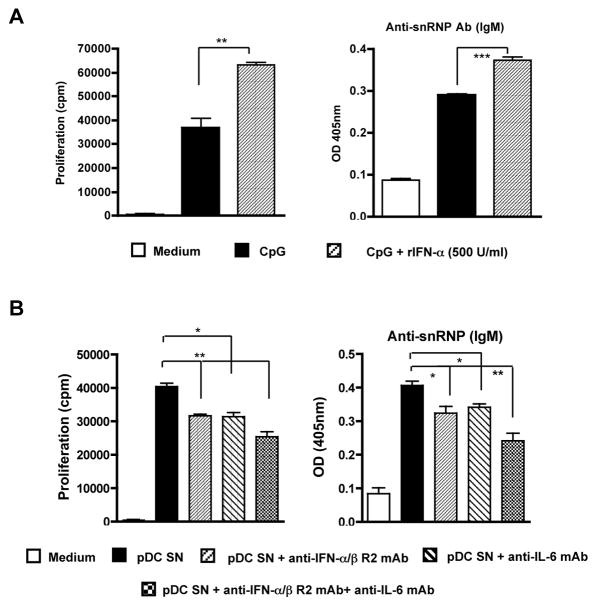

Type I IFN and IL-6 have been reported to induce B cell differentiation and enhance Ab production. To determine the possible mediators secreted by pDCs to induce enhanced autoreactive B cell proliferation and autoAb production, we measured autoreactive B cell activation upon TLR stimulation in the presence of rIFN-α. Indeed, rIFN-α significantly increased CpG-induced autoreactive B cell proliferation and autoAb production (Fig. 4A). However, rIL-6 did not significantly increase CpG-induced autoreactive B cell proliferation (data not shown). This could be due to the fact that CpG stimulates B cells to secrete IL-6. Thus, the addition of exogenous IL-6 cannot show the additive effect on the enhancement of CpG-induced B cell proliferation. In addition, we used anti-IL-6 mAb or anti-type I IFNα/β receptor mAb to block the IL-6 or IFN-α/β activity. As shown in Fig. 4B, both neutralizing mAbs significantly, but only partially, decreased CpG-stimulated pDC supernatant-induced B cell proliferation and autoAb production. Similar results were observed when autoreactive B cells were stimulated with TLR7 ligand (data not shown). These data suggest that cytokines IL-6 and INF-α/β partially contribute to pDC-mediated enhancement of autoreactive B cell activation.

Figure 4.

Type I IFNs and IL-6 partially contribute to the enhancement of autoreactive B cell activation via pDCs. A, Purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (1×105/well) were stimulated by CpG with or without recombinant mouse IFN-α (500 U/ml). B cell proliferation and anti-snRNP autoAb production were determined. B, pDCs were stimulated with CpG (0.3 μg/ml) for 24 h. The culture supernatants were harvested and mixed with purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (1 ×105/well) for 48 h (proliferation assay) or 120 h (autoAb assay) in the presence of anti-IFN-α/β R2 mAb (1 μg/ml) and/or anti-IL-6 mAb (1 μg/ml) or isotype control mAbs. Data are representative of three independent experiments. * p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Cell-to-cell contact is also required for pDC-mediated autoreactive B cell activation

In addition to the soluble cytokines secreted by pDCs, it is unclear whether cell-to-cell contact is also required for pDCs to mediate these effects. To this end, pDCs and autoreactive B cells were co-cultured in a transwell system. As shown in Fig. 5A, separation of pDCs and autoreactive B cells significantly reduced the costimulatory capacity of pDCs to increase autoreactive B cell proliferation. Similarly, autoAb production was also significantly decreased. Despite reduced autoreactive B cell proliferation and autoAb production in transwell assays, B cells separated from pDCs by the transwell system still proliferated more compared to B cells stimulated with TLR ligand alone in the absence of pDCs, suggesting a contribution of soluble mediators.

Figure 5.

Cell-to-cell contact is required for pDC-mediated enhanced B cell proliferation. A, Purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (5×105/well) and pDCs (1.25×105/well) were co-cultured in separated compartments using a transwell system in the presence of CpG (0.1 μg/ml) or Gardiquimod (0.5 μg/ml) for 48 h. The data suggest that enhanced B cell proliferation in the presence of pDCs is significantly reduced in transwell assays. B, Purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (1 ×105/well) were cultured in the presence of CpG (0.1 μg/ml) or Gardiquimod (0.1 μg/ml) with or without fixed, pre-activated pDCs (1.25×105/well). C, Freshly isolated or CpG-activated pDCs were fixed and co-cultured with purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (1×105/well) in the presence of CpG (0.1 μg/ml). The percentage of enhancement was calculated using the formula: cpm (B cells + pDCs) / cpm (B cell alone) × 100% (n=3). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To further confirm that cell-to-cell contact is required for pDC-mediated effect, pDCs were pre-activated with TLR7- or TLR9 ligand and then fixed with paraformaldehyde to eliminate their capability for cytokine secretion (data not shown). Activated and fixed pDCs were then co-cultured with autoreactive B cells. These pDCs significantly increased autoreactive B cell proliferation (Fig. 5B) and autoAb production (data not shown) in response to TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation. This is also the case for BCR ligation-induced B cell proliferation (Fig. 1C). The enhancement is only mediated by activated pDCs, as freshly isolated pDCs did not have a similar costimulatory effect (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that activated pDCs provide costimulatory signals to autoreactive B cells via cell-to-cell contact in addition to soluble factors.

The ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway is involved in the pDC-autoreactive B cell interaction

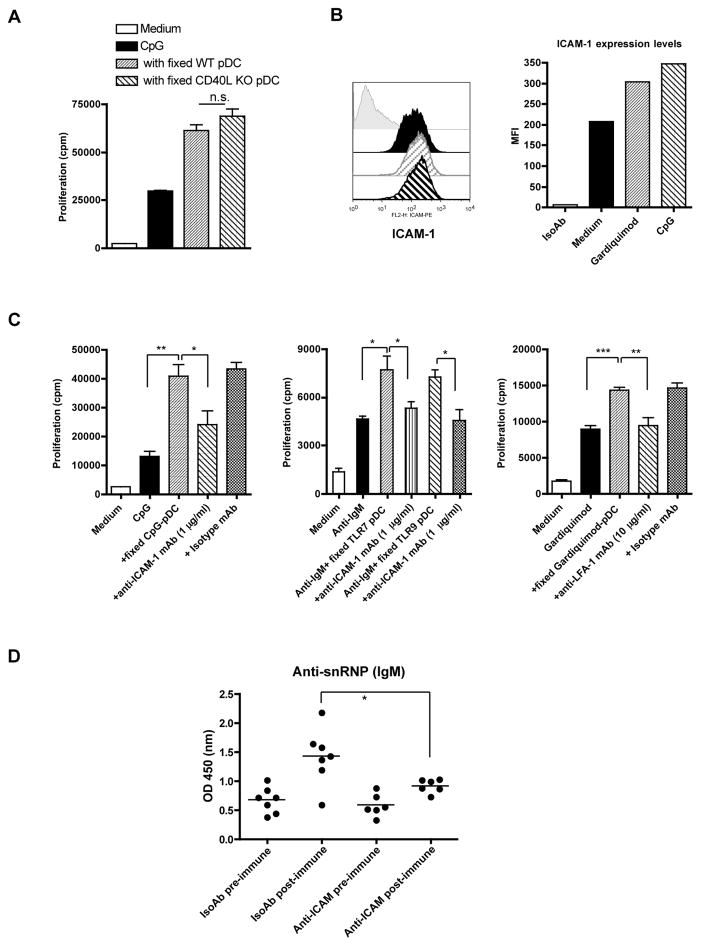

Because cell-to-cell contact is required for the enhanced activation of anti-snRNP B cells mediated by pDCs, we determined the membrane molecules involved in this interaction. Many surface molecules such as CD40, CD80, CD86, CD70, and CD83 were upregulated in pDCs upon TLR ligand stimulation. CD40L was also expressed on TLR ligand-stimulated pDCs (data not shown). The CD40-CD40L pathway is crucial for B cell activation including Ab production, isotype switching and germinal center formation (27). Signaling through CD70-CD27 can also regulate B cell activation and Ig production (28, 29). The rationale to determine the membrane molecules involved in this process is that either ligand or receptor is expressed on pDCs or B cells. Therefore, the CD40 (B cells)-CD40L (pDCs) and CD27 (B cells)-CD70 (pDCs) pathways were further investigated. However, CD40L-deficient pDCs had a similar costimulatory capacity as wildtype (WT) pDCs to trigger anti-snRNP Tg B cell proliferation and autoAb production (Fig. 6A and data not shown). Similarly, the CD27-CD70 pathway did not have a significant role in pDC-mediated enhancement of B cell activation as neutralizing Abs did not significantly alter pDC’s costimulatory effect (data not shown).

Figure 6.

The LFA-1-ICAM-1 pathway, but not the CD40-CD40L pathway, contributes to the pDC-autoreactive B cell interaction. A, CpG-activated pDCs from WT or CD40L−/− mice were fixed and then co-cultured with purified anti-snRNP Tg B cells (1×105/well) in the presence of CpG (0.1 μg/ml). B, ICAM-1 expression levels on pDCs stimulated with CpG (0.1 μg/ml) or Gardiquimod (0.1 μg/ml) for 48 h were analyzed by flow cytometry and the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was shown. C, Purified B cells (1×105/well) were cultured with fixed, preactivated pDCs (0.25×105/well) in the presence of CpG (0.1 μg/ml), Gardiquimod (0.1 μg/ml), or anti-IgM (10 μg/ml) with or without blocking anti-ICAM-1 mAb (1 μg/ml) or anti-LFA-1 mAb (10 μg/ml) and corresponding isotype control mAbs. D, Anti-snRNP Tg mice (n=6 or 7) were injected with anti-ICAM-1 blocking mAb or isotype mAb at days -3, -1, 1, and 3. Mice were immunized with CpG at days 1 and 4. Sera were collected at day 7 to detect anti-snRNP Ab level (1:100 dilution). Data are representative of two or more independent experiments. * p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

LFA-1 belongs to the integrin family of cell adhesion molecules and is expressed on leukocytes, including B cells (30). Its main ligand, ICAM-1 (CD54), is expressed widely on DCs, leukocytes, and endothelial cells. LFA-1/ICAM-1 has been implicated in the physical interaction between B cells and conventional DCs and B cells and follicular DCs (FDCs) (31, 32). The interaction of ICAM-1-LFA-1 reduces the B cell activation threshold via facilitating B cell adhesion and synapse formation (33). ICAM-1 expression levels on pDCs were significantly increased upon TLR ligand stimulation (Fig. 6B). To determine whether the ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway involves pDCs-B cell interaction, neutralizing anti-LFA or anti-ICAM-1 mAbs were used. As shown in Figure 6C, anti-ICAM-1 or anti-LFA-1 neutralizing mAbs, but not isotype control mAbs, significantly abrogated activated, fixed pDC-mediated autoreactive B cell proliferation in response to both TLR and BCR stimulation. Similarly, autoAb production was also significantly reduced (data not shown).

To further examine whether the ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway plays a critical role in autoreactive B cell activation in vivo, we treated anti-snRNP Tg mice with anti-ICAM-1 blocking mAb and then immunized mice with CpG. As shown in Fig. 6D, anti-snRNP autoAb production was significantly lower in anti-ICAM-1 mAb-treated mice compared to that in isotype mAb-treated mice.

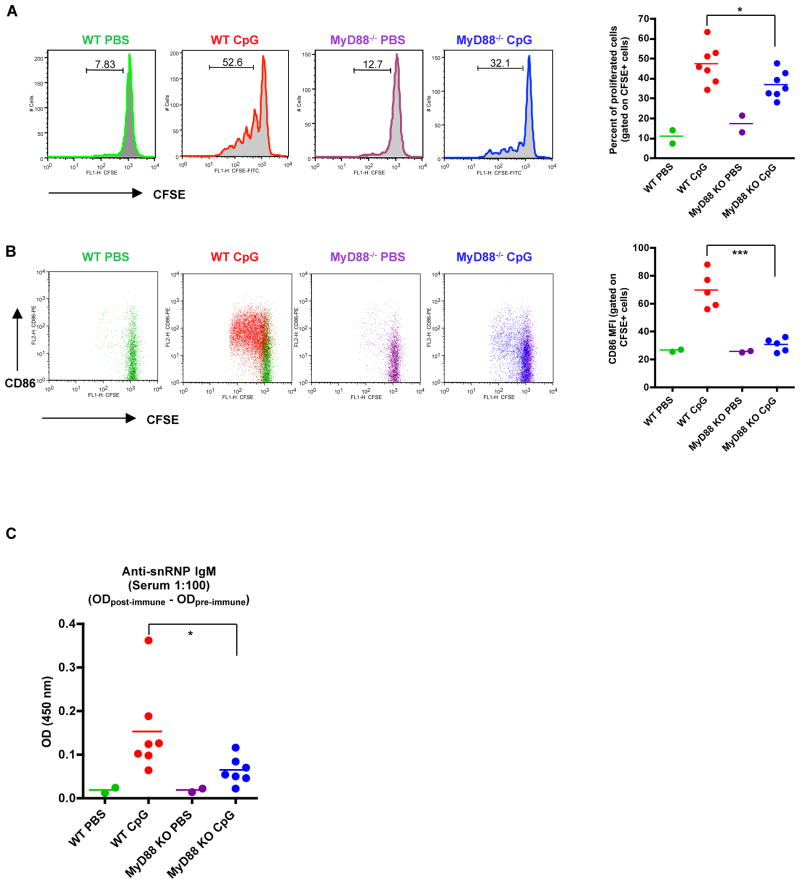

Decreased B cell proliferation, costimulatory activation, and autoAb production in vivo in the absence of pDCs’ help

To explore whether pDCs also provide helper signals for autoreactive B cell in vivo activation, anti-snRNP B cells were purified, fluorescent labeled, and then adoptively transferred into WT or MyD88−/− mice. Recipient mice were then immunized with or without TLR7/9 ligand and B cell proliferation and activation were examined. In this system, TLR7/9 ligand activates both anti-snRNP B cells and pDCs in WT recipient mice. However, only anti-snRNP B cells are responsive to TLR stimulation in MyD88-deficient recipient mice. As shown in Fig. 7A, anti-snRNP B cells proliferated vigorously in WT recipient mice immunized with TLR9 ligand. In contrast, autoreactive B cells did not proliferate as much in MyD88−/− recipient mice. As controls, anti-snRNP B cells had minimal proliferation in WT or MyD88−/− mice without TLR9 ligand immunization. In addition, costimulatory molecule CD86 expression levels on autoreactive B cells were also significantly lower in MyD88−/− mice compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 7B). Similarly, autoreactive B cells in MyD88−/− recipient mice produced significantly fewer autoAbs with respect to those in WT mice (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that activation of autoreactive B cells in vivo requires helper signals from pDCs.

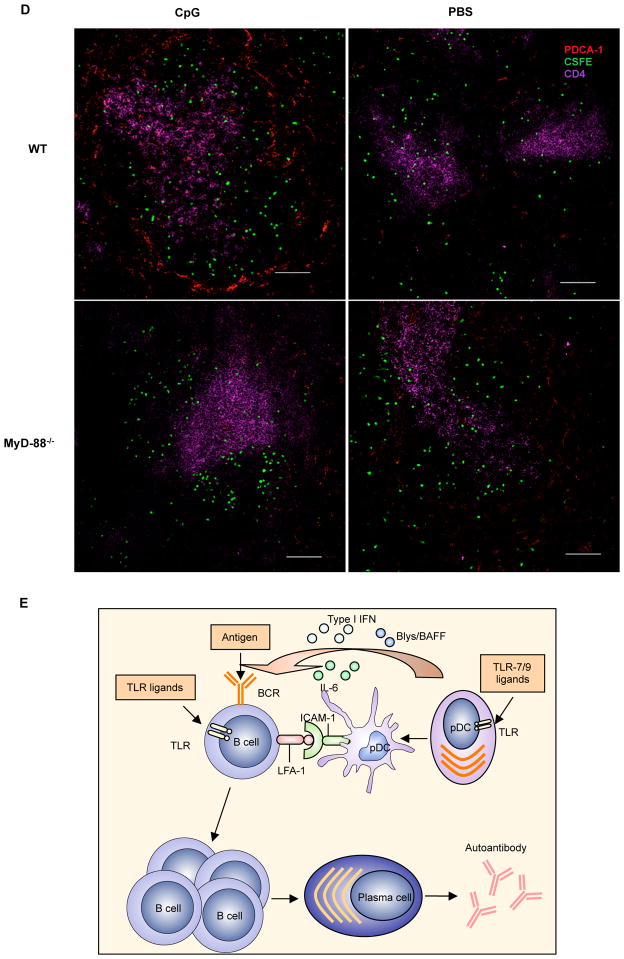

Figure 7.

Autoreactive B cell proliferation and activation in vivo. Purified autoreactive B cells were labeled with CFSE and adoptively transferred into C57Bl/6 mice or MyD88−/− mice. Recipient mice were immunized i.v. with CpG at 100 μg/injection on days 1 and 4 and sacrificed at day 7. B cell division and CD86 expression were examined by flow cytometry. Anti-snRNP IgM response was measured by ELISA. A, Proliferation of transferred B cells and the percentage of proliferated B cells gated on CFSE+ population. B, CD86 expression on autoreactive B cells. MFI of CD86 expression on the CFSE+ cells is shown. C, Anti-snRNP IgM response in recipient mice of a 1:100 dilution of serum. The OD value of the pre-immune sera subtracted from the post-immune sera is shown. * p<0.05, **p<0.01. D, Location of pDCs and autoreactive B cells. Anti-snRNP Tg B cells were purified and labeled with CFSE (green) and then adoptively transferred into WT or MyD88−/− mice. Recipient mice were then injected i.v. with 100 μg CpG or PBS for 24 h. Sections of spleens were stained with anti-CD4 (T cells; purple) and anti-mPDCA-1 (pDCs; red) mAbs. Bar, 100 μm. (E) Schematic model of pDC-autoreactive B cell interaction.

To determine in vivo interaction between pDCs and autoreactive B cells, autoreactive B cells were CFSE labeled and then adoptively transferred into WT or MyD-88−/− mice. Mice were immunized with or without TLR9 ligand and spleen sections from different groups were stained with pDCs and CD4 mAbs. In the spleens of PBS immunized WT or MyD88−/− mice, pDCs were localized in T zone and marginal zone with lower numbers (Fig. 7D). Autoreactive B cells resided in the follicle. MyD88−/− mice with CpG immunization displayed similar pattern as PBS immunized mice. However, pDCs were significantly increased and localized in both T zone and marginal zone in WT mice immunized with CpG. Autoreactive B cells were predominately located in the T-B cell interface and marginal zone with pDCs, suggesting pDC-autoreactive B cell interaction.

Discussion

In this study, we found that activated pDCs interact with autoreactive B cells for augmented proliferation and autoAb production in response to TLR and BCR stimulation. TLR7/9 ligands can directly activate autoreactive B cells for proliferation and autoAb production despite their anergic phenotype. However, their full activation appears to be dependent on activated pDCs. Activated pDCs not only provide soluble mediators including type I IFN, IL-6, and BLys/BAFF to stimulate autoreactive B cell differentiation to Ab-secreting plasma cells and promote B cell survival but also directly interact with autoreactive B cells via the ICAM-1-LFA-1 costimulatory pathway.

There is accumulating evidence to suggest that autoreactive B cells can be activated to secrete pathogenic autoAbs via a T-cell independent pathway. For example, activation of anti-snRNP B cells and AM14 rheumatoid factor B cells via TLR ligands does not absolutely require T cells but depends on the TLR pathway (34, 35). However, it is unknown whether autoreactive B cell activation in this manner requires interaction with other cell types. Previous studies have shown that anti-chromatin-CpG complex or U1 snRNP immune complex can activate pDCs to produce type I IFN (4, 5). These immune complexes also activate autoreactive B cells simultaneously. Thus, activated pDCs could provide further costimulatory activity to autoreactive B cells, leading to augmented pathogenic autoAb secretion. It may also stimulate autoreactive B cells to be potent APCs for autoreactive T cell activation. Interestingly, blockade of TLR7 and TLR9 with immunoregulatory sequence 954 in lupus-prone mice resulted in significant reduction of autoAb production and amelioration of disease progression (36). It is worth noting that enhanced autoreactive B cell activation mediated by activated pDCs occurs when autoreactive B cells were stimulated with lower concentration of TLR or BCR stimulation. The pDC-mediated enhancement effect was less significant when autoreactive B cells were stimulated with higher concentrations of TLR ligands or BCR ligation (data not shown). This phenomenon may reflect the physiological situation in which trace amounts of endogenous TLR ligands induce autoreactive B cell activation to generate canonical autoAbs through a pDC-mediated activation amplification loop. Indeed, SLE patients have elevated levels of circulating plasma DNA that is enriched in hypomethylated CpGs (37). Genomic DNA is also hypomethylated in SLE patients. These danger triggers could serve as initial stimuli to induce autoreactive B cell activation through interaction with pDCs in a T-cell independent manner. This effect could be also possibly extended to other B cells with different Ag specificity. Indeed, anti-nitrophenyl B cell activation was also augmented in the presence of activated pDCs (data not shown).

Another possible mediator is pDC-secreted exosome. Previous studies have shown that activated DCs secrete bona fide exosomes (38). These exosomes express MHC class II and costimulatory molecules such as ICAM-1 and play a critical role in T cell activation (38, 39). To address whether pDC exosomes have stimulatory effect on autoreactive B cell activation, supernatants from CpG or gardiquimod-activated pDCs were harvested and ultracentrifuged to deprive exosomes. Autoreactive B cell proliferation was comparable between non-centrifuged and centrifuged gardiquimod-activated pDC supernatants (data not shown). In contrast, the stimulatory effect of CpG-activated pDC supernatants on B cells was significantly decreased after ultracentrifugation (data not shown). However, we found that the ultracentrifugation also removed the remaining CpG in supernatants since control medium with CpG lost its stimulatory effect after ultracentrifugation. Thus, it is unlikely that exosomes secreted by activated pDCs contribute to pDC-mediated enhancement of autoreactive B cell activation. This notion is supported by a recent study showing that activated DC exosomes did not induce B cell proliferation (40).

We found that pDCs regulate autoreactive B cell activation via soluble mediators as well as through cell-to-cell contact. It is not surprising that soluble cytokines including type I IFN and IL-6 are involved in autoreactive B cell differentiation into autoAb-secreting plasma cells as reported previously in human B cell studies (13, 14). The intriguing finding is that cell-to-cell contact between pDCs and autoreactive B cells is also necessary for augmented autoreactive B cell activation. This notion is supported by both transwell assays and by using fixed, pre-activated pDCs to eliminate cytokine secretion capability. Our initial attempts to discover possible costimulatory molecule pathways involved in this interaction were focused mainly on the CD40-CD40L and CD27-CD70 pathways, given their importance in regulating B cell activation (27, 28). To our surprise, neither of these pathways showed significant roles in the pDC-autoreactive B cell interaction. The ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway has been shown to be critical in regulating B cell activation threshold (33). Therefore, we investigated this pathway and found that blockade of the ICAM-1-LFA-1 interaction significantly attenuates pDC-induced enhancement of autoreactive B cell activation in vitro. Moreover, in vivo blockade of ICAM-1-LFA-1 interaction using blocking mAb significantly decreased autoAb production. CpG-DNA derived from lupus serum has been shown to induce ICAM-1 upregulation (41). Notably, ICAM-1 is also expressed on B cells and its expression levels were significantly increased upon CpG or gardiquimod stimulation. However, CpG-, gardiquimode-, or anti-IgM-induced B cell proliferation was not inhibited by blocking anti-ICAM-1 mAb (data not shown), suggesting that decreased B cell proliferation is not due to inhibition of B cell itself. Although ICAM-1 is constitutively expressed on pDCs, freshly isolated pDCs failed to induce enhanced B cell activation. This may be related to the conformational change of LFA-1-ICAM-1 after TLR7/9 ligand stimulation. LFA-1 (αLβ2) belongs to the β2-integrin family and mediates cell-to-cell and cell-to-extracellular matrix adhesions essential for immune and inflammatory responses (42). One critical mechanism regulating LFA-1 activity is the conformational change of the ligand-binding αL-I domain from low-affinity to high-affinity (43). The inserted (I) domain of LFA-1 contains the ligand-binding epitope and a conformational change in this region during activation increases ligand affinity (44). Thus, upregulated ICAM-1 on pDCs may bind to the high affinity of LFA-1 to induce “outside in” signals to autoreactive B cells. Interestingly, loss of LFA-1 or ICAM-1 significantly reduces anti-dsDNA autoAb production and decreases glomerulonephritis (45, 46), suggesting critical roles of the ICAM-1-LFA-1 pathway for autoreactive B cell regulation.

We further demonstrated that autoreactive B cell activation in vivo also requires pDC help. It is clear that autoreactive B cell proliferation, CD86 costimulatory molecule expression levels, and autoAb production were significantly reduced in MyD-88-deficient recipient mice as compared to those in WT recipient mice. Autoreactive anti-snRNP B cells are of an immature phenotype and have decreased CD86 expression to induce autoreactive T cell tolerance (20, 47). Enhanced CD86 expression may suggest possible autoreactive T cell activation. In mice, pDCs and conventional mDCs both express TLR7 and TLR9 (48). We initially used a pDC-depleting mAb to address this issue. However, pDCs were not effectively depleted in our systems. Therefore, the reduced autoreactive B cell activation in vivo could be contributed by both DC types. Indeed, mDCs have been shown to stimulate B cell proliferation and differentiation through the secretion of soluble mediators including IL-6 and IL-12 as well as membrane molecules such as BAFF/APRIL (49, 50). Moreover, activated DCs from lupus-prone mice directly increase B cell effector functions(40). A recent study demonstrated that pDCs and mDCs may differentially regulate B cell responses (51). pDCs, but not mDCs, predominately enhance B cell activation upon TLR7/8 ligand stimulation and, to a lesser extent, TLR9 ligand stimulation. Nevertheless, in vivo trafficking studies show that pDCs are significantly expanded upon TLR stimulation and trafficked into both T zone and marginal zone to interact with autoreactive B cells. These data suggest that interactions between pDCs and autoreactive B cells take place in vivo to induce augmented B cell activation.

On the basis of our results, we postulate a schematic model to explain how pDCs interact with autoreactive B cells for pathogenic autoAb production (Fig. 7E). Endogenous plasma DNA/RNA or DNA/RNA-containing immune complexes activate pDCs to secrete type I IFNs, IL-6, and BLys/BAFF. Activated pDCs upregulate ICAM-1 expression and engage LFA-1 on autoreactive B cells. Simultaneously, autoreactive B cells are activated by plasma DNA/RNA or DNA/RNA-containing immune complexes or are engaged by self-Ag stimulation via BCR. Secreted type I IFNs and IL-6 enhance autoreactive B cell differentiation and BLys/BAFF promotes autoreactive B cell survival. In addition, up-regulated ICAM-1 on activated pDCs binds high affinity LFA-1 on B cells to lower activation threshold for autoreactive B cells. Taken together, these events lead to augmented autoreactive B cell expansion, plasma cell differentiation, and autoAb production. Further understanding of the cellular and molecular events of the pDC-B cell interaction will help us to comprehend autoreactive B cell activation, differentiation, or autoimmunity.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- pDCs

plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- TLR

Toll-like recepotr

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- Tg

transgenic

- snRNP

small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle

- mDCs

myeloid dendritic cells

- BAFF

B cell activating factor

- APRIL

a proliferation-inducing ligand

- Blys

B lymphocyte stimulating protein

- FDC

follicular dendritic cells

- WT

wildtype

- TACI

transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor

Footnotes

This study was supported by research funding from American College of Rheumatology and Arthritis Foundation. JY is a recipient of American College of Rheumatology and Arthritis Foundation Investigator Award. This research was supported in part by NIH R01 DK52294 and HL63442, and the University of Louisville Hospital to STI. CD is a recipient of Arthritis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Award.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Liu YJ. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:275–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farkas L, Beiske K, Lund-Johansen F, Brandtzaeg P, Jahnsen FL. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon- alpha/beta-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61689-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cederblad B, Blomberg S, Vallin H, Perers A, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have reduced numbers of circulating natural interferon-alpha- producing cells. J Autoimmun. 1998;11:465–470. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Means TK, Latz E, Hayashi F, Murali MR, Golenbock DT, Luster AD. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate DCs through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:407–417. doi: 10.1172/JCI23025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savarese E, Chae OW, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Kastner B, Akira S, Wagner H, Schmid RM, Bauer S, Krug A. U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein immune complexes induce type I interferon in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Blood. 2006;107:3229–3234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vollmer J, Tluk S, Schmitz C, Hamm S, Jurk M, Forsbach A, Akira S, Kelly KM, Reeves WH, Bauer S, Krieg AM. Immune stimulation mediated by autoantigen binding sites within small nuclear RNAs involves Toll-like receptors 7 and 8. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1575–1585. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preble OT, Black RJ, Friedman RM, Klippel JH, Vilcek J. Systemic lupus erythematosus: presence in human serum of an unusual acid-labile leukocyte interferon. Science. 1982;216:429–431. doi: 10.1126/science.6176024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanco P, Palucka AK, Gill M, Pascual V, Banchereau J. Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science. 2001;294:1540–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1064890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baechler EC, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. The emerging role of interferon in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:801–807. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dall'era MC, Cardarelli PM, Preston BT, Witte A, Davis JC., Jr Type I interferon correlates with serological and clinical manifestations of SLE. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1692–1697. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ, Shark KB, Grande WJ, Hughes KM, Kapur V, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santiago-Raber ML, Baccala R, Haraldsson KM, Choubey D, Stewart TA, Kono DH, Theofilopoulos AN. Type-I interferon receptor deficiency reduces lupus-like disease in NZB mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197:777–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jego G, Palucka AK, Blanck JP, Chalouni C, Pascual V, Banchereau J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity. 2003;19:225–234. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poeck H, Wagner M, Battiany J, Rothenfusser S, Wellisch D, Hornung V, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells, antigen, and CpG-C license human B cells for plasma cell differentiation and immunoglobulin production in the absence of T-cell help. Blood. 2004;103:3058–3064. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Bon A, Thompson C, Kamphuis E, Durand V, Rossmann C, Kalinke U, Tough DF. Cutting edge: enhancement of antibody responses through direct stimulation of B and T cells by type I IFN. J Immunol. 2006;176:2074–2078. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Bon A, Schiavoni G, D'Agostino G, Gresser I, Belardelli F, Tough DF. Type i interferons potently enhance humoral immunity and can promote isotype switching by stimulating dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 2001;14:461–470. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litinskiy MB, Nardelli B, Hilbert DM, He B, Schaffer A, Casali P, Cerutti A. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekeredjian-Ding IB, Wagner M, Hornung V, Giese T, Schnurr M, Endres S, Hartmann G. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control TLR7 sensitivity of naive B cells via type I IFN. J Immunol. 2005;174:4043–4050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santulli-Marotto S, Retter MW, Gee R, Mamula MJ, Clarke SH. Autoreactive B cell regulation: peripheral induction of developmental arrest by lupus-associated autoantigens. Immunity. 1998;8:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan J, Mamula MJ. Autoreactive T cells revealed in the normal repertoire: escape from negative selection and peripheral tolerance. J Immunol. 2002;168:3188–3194. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilliet M, Boonstra A, Paturel C, Antonenko S, Xu XL, Trinchieri G, O'Garra A, Liu YJ. The development of murine plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors is differentially regulated by FLT3-ligand and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 2002;195:953–958. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brawand P, Fitzpatrick DR, Greenfield BW, Brasel K, Maliszewski CR, De Smedt T. Murine plasmacytoid pre-dendritic cells generated from Flt3 ligand-supplemented bone marrow cultures are immature APCs. J Immunol. 2002;169:6711–6719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan J, Mamula MJ. B and T cell tolerance and autoimmunity in autoantibody transgenic mice. Int Immunol. 2002;14:963–971. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Culton DA, O'Conner BP, Conway KL, Diz R, Rutan J, Vilen BJ, Clarke SH. Early preplasma cells define a tolerance checkpoint for autoreactive B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:790–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craxton A, Magaletti D, Ryan EJ, Clark EA. Macrophage- and dendritic cell--dependent regulation of human B-cell proliferation requires the TNF family ligand BAFF. Blood. 2003;101:4464–4471. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do RK, Hatada E, Lee H, Tourigny MR, Hilbert D, Chen-Kiang S. Attenuation of apoptosis underlies B lymphocyte stimulator enhancement of humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 2000;192:953–964. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishop GA, Hostager BS. The CD40-CD154 interaction in B cell-T cell liaisons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arens R, Nolte MA, Tesselaar K, Heemskerk B, Reedquist KA, van Lier RA, van Oers MH. Signaling through CD70 regulates B cell activation and IgG production. J Immunol. 2004;173:3901–3908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Y, Hendriks J, Langerak P, Jacobs H, Borst J. CD27 is acquired by primed B cells at the centroblast stage and promotes germinal center formation. J Immunol. 2004;172:7432–7441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dang LH, Rock KL. Stimulation of B lymphocytes through surface Ig receptors induces LFA-1 and ICAM-1-dependent adhesion. J Immunol. 1991;146:3273–3279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koopman G, Parmentier HK, Schuurman HJ, Newman W, Meijer CJ, Pals ST. Adhesion of human B cells to follicular dendritic cells involves both the lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1/intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and very late antigen 4/vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 pathways. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1297–1304. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kushnir N, Liu L, MacPherson GG. Dendritic cells and resting B cells form clusters in vitro and in vivo: T cell independence, partial LFA-1 dependence, and regulation by cross-linking surface molecules. J Immunol. 1998;160:1774–1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carrasco YR, Fleire SJ, Cameron T, Dustin ML, Batista FD. LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction lowers the threshold of B cell activation by facilitating B cell adhesion and synapse formation. Immunity. 2004;20:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding C, Wang L, Al-Ghawi H, Marroquin J, Mamula M, Yan J. Toll-like receptor engagement stimulates anti-snRNP autoreactive B cells for activation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2013–2024. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herlands RA, Christensen SR, Sweet RA, Hershberg U, Shlomchik MJ. T cell-independent and toll-like receptor-dependent antigen-driven activation of autoreactive B cells. Immunity. 2008;29:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Chan JH, Guiducci C, Coffman RL. Treatment of lupus-prone mice with a dual inhibitor of TLR7 and TLR9 leads to reduction of autoantibody production and amelioration of disease symptoms. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3582–3586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieg AM. CpG DNA: a pathogenic factor in systemic lupus erythematosus? J Clin Immunol. 1995;15:284–292. doi: 10.1007/BF01541318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segura E, Amigorena S, Thery C. Mature dendritic cells secrete exosomes with strong ability to induce antigen-specific effector immune responses. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Buschow SI, Anderton SM, Stoorvogel W, Wauben MH. Activated T cells recruit exosomes secreted by dendritic cells via LFA-1. Blood. 2009;113:1977–1981. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wan S, Zhou Z, Duan B, Morel L. Direct B cell stimulation by dendritic cells in a mouse model of lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1741–1750. doi: 10.1002/art.23515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyata M, Ito O, Kobayashi H, Sasajima T, Ohira H, Suzuki S, Kasukawa R. CpG-DNA derived from sera in systemic lupus erythematosus enhances ICAM-1 expression on endothelial cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:685–689. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.7.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bolomini-Vittori M, Montresor A, Giagulli C, Staunton D, Rossi B, Martinello M, Constantin G, Laudanna C. Regulation of conformer-specific activation of the integrin LFA-1 by a chemokine-triggered Rho signaling module. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:185–194. doi: 10.1038/ni.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang L, Shimaoka M, Rondon IJ, Roy I, Chang Q, Po M, Dransfield DT, Ladner RC, Edge AS, Salas A, Wood CR, Springer TA, Cohen EH. Identification and characterization of a human monoclonal antagonistic antibody AL-57 that preferentially binds the high-affinity form of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:905–914. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105649.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pepper LR, Hammer DA, Boder ET. Rolling adhesion of alphaL I domain mutants decorrelated from binding affinity. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kevil CG, Hicks MJ, He X, Zhang J, Ballantyne CM, Raman C, Schoeb TR, Bullard DC. Loss of LFA-1, but not Mac-1, protects MRL/MpJ-Fas(lpr) mice from autoimmune disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:609–616. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63325-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bullard DC, King PD, Hicks MJ, Dupont B, Beaudet AL, Elkon KB. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 deficiency protects MRL/MpJ-Fas(lpr) mice from early lethality. J Immunol. 1997;159:2058–2067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cambier JC, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Vilen BJ. B-cell anergy: from transgenic models to naturally occurring anergic B cells? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dubois B, Vanbervliet B, Fayette J, Massacrier C, Van Kooten C, Briere F, Banchereau J, Caux C. Dendritic cells enhance growth and differentiation of CD40-activated B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1997;185:941–951. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacLennan I, Vinuesa C. Dendritic cells, BAFF, and APRIL: innate players in adaptive antibody responses. Immunity. 2002;17:235–238. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Douagi I, Gujer C, Sundling C, Adams WC, Smed-Sorensen A, Seder RA, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Lore K. Human B cell responses to TLR ligands are differentially modulated by myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1991–2001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]