Abstract

For head and neck as well as for oromaxillofacial surgery, the use of the pectoralis major myocutaneous (PMMC) flap is a standard reconstructive technique after radical surgery for cancers in this region. We report to our knowledge for the first development of breast cancer in the PMMC flap in a 79 year old patient, who had undergone several operations in the past for recurring squamous cell carcinoma of the jaw. The occurrence of a secondary malignancy within the donor tissue after flap transfer is rare, but especially in the case of transferred breast tissue and the currently high incidence of breast cancer theoretically possible. Therefore preoperative screening mammography seems advisable to exclude a preexisting breast cancer in female patients undergoing such reconstruction surgery. Therapy for breast cancer under these circumstances is individual and consists of radical tumor resection followed by radiation if applicable and a standard systemic therapeutic regimen on the background of the patients individual prognosis due to the primary cancer.

Keywords: Secondary malignancy, squamous cell carcinoma, neck dissection, recurrence, transplanted breast parenchyma, myocutaneous flap

Introduction

The pectoralis major myocutaneous (PMMC) flap is a standard reconstructive technique in patients with cancers in the neck and face and is able to cover major anatomical defects arising from of such radical cancer surgery. In general, transferred flap tissue includes the skin, subcutaneous fat and the corresponding muscle with a vascular pedicle. The recurrence of the originally resected tumor or the development of cancer of the skin within the flap tissue is extremely rare [1,2]. However, the possibility of a new tumor arising from the transplant tissue should be addressed before such a procedure is performed. The PMMC flap, which was first reported by Ariyan in 1979, is one of the standard reconstructive procedures after radical cancer surgery for neck and face cancers. Other indications include the coverage of fistulas of the sternum, chest wall defects and it is sometimes used for breast reconstructions after breast cancer surgery [3-5].

A particular characteristic of the PMMC flap is the dissection of the skin-island with the underlying subcutaneous tissue which invariably results in the transplantation of some breast tissue. Also due to the anatomical variation of the female breast, particularly the spread and the existence of aberrant breast parenchyma may invariably result in some glandular epithelial tissue being transplanted. Therefore, the occurrence of breast cancer in a PMMC flap is theoretically possible, considering the high incidence of this malignancy.

In this presented case, the patient underwent surgery for a primary neck cancer in 1994. Several recurrences in the following years required reoperations, so that finally in 1997 the patient needed a PMMC flap to cover the anatomical defect. The diagnosis of breast cancer in the PMMC tissue was confirmed four years later in 2001, after the patient had presented herself to the hospital for a palpable mass in the flap.

This case underlines that development of primary breast cancer in the transferred tissue should be kept in mind as a differential diagnosis to local tumor recurrence in a female patient. Furthermore, a basic pre-operative apparative screening seems reasonable for female patients prior to a PMMC flap surgery.

Case report

The patient was initially diagnosed with a squamous cell carcinoma of the right alveolar process. She then underwent a neck dissection, resection of partial mandible, cheek and floor of the mouth with mandible reconstruction using MRS plates in February of 1994. The final histology revealed a pT4 pN0 G2cM0. As a postoperative measure, the patient underwent a percutaneous radiation of the mouth, oropharynx and cervical lymph nodes with a total radiation dosage of 60.2 Gy directed to the region of the carcinoma and 48.5 Gy to the region of the lymph node drainage. She was not administered any systemic therapy. The first recurrence was diagnosesd in August 1995, whereby the tumor was surgically removed and the anatomy reconstructed using a transposition flap. The second recurrence in April 1997 occurred on the edge of the right tongue and required further surgery including a right hemiglossectomy, partial right cheek removal and the reconstruction with a PMMC flap. In the operation report it was noted that the muscle tissues were extremely hypotrophic, probably due to the much reduced alimentary and nutritional condition of the patient. Moreover, it described the dissection of the myocutaneous pectoral muscle and its vascular pedicle of the thoracoacromial artery and vein, followed by rotation as well as tunneling of the flap under the right clavicle and along the carotid artery for covering an oral defect of 6.5 × 4.5 cm2. During routine follow-ups, a biopsy was taken in April 1998 from the base of the tongue due to a palpable mass in close proximity to the PMMC flap revealing a fibroma. In February 1999, the patient was diagnosed with a second carcinoma originating from the alveolar process of the right upper jaw. This resulted in partial maxillary excision and the histology showed a 1.6 cm in diameter measuring squamous cell carcinoma. The margins showed dysplasia and chronic inflammation free of malignancy.

Finally, in September 2001 as part of the routine follow-ups, the patient was diagnosed with an extraoral palpable and indurate mass. Ultrasonographically an inhomogenous and markedly hypoechoic lesion in the area of the PMMC flap was detected. A core needle biopsy taken from the lesion showed an invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Following the diagnosis, the patient was transferred to our unit for further work-up.

The clinical examination revealed a patient with obvious cachexia weighing 43 kg with 165 cm body height. Her medical history was uneventful for any other illnesses, apart from the above mentioned and her gynecological history just revealed an abrasion in 1957 and a senile kolpitis at present, being under therapy with topical applications of an estrogen-containing ointment for approximately 6-9 months. She was a gravida II, para II with uneventful pregnancies and normal labor. The family history was non-contributory for genetic disorders or breast cancer, but one of her sons had died at the age of 45 years due to a rare malignancy of the adrenal cortex.

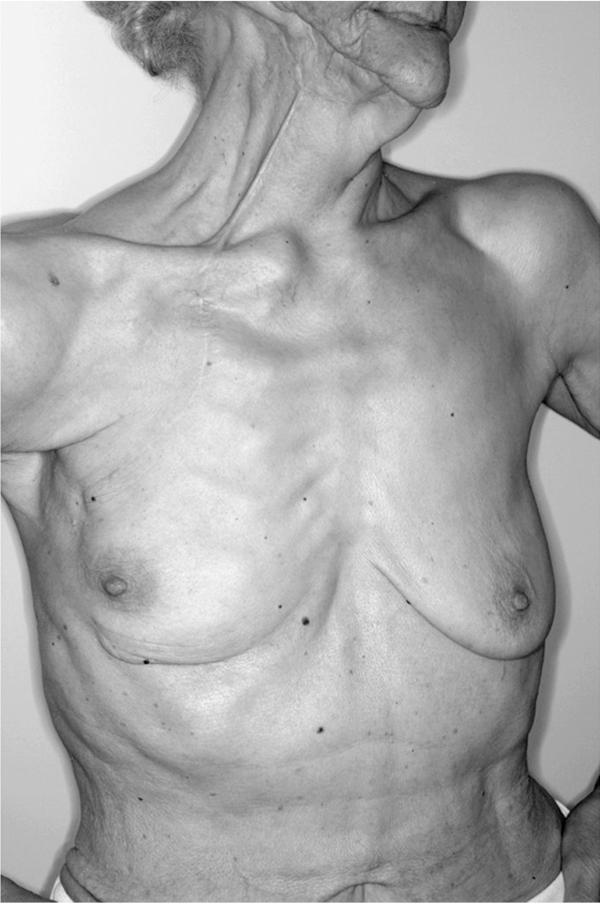

The inspection and palpation of the right cheek and lower jaw showed induration and multiple scars as shown in Figure 1 and a palpable mass measuring approximately 2 × 1.5 cm. The sonography of the mass revealed a hypoechoic lesion measuring 1.2 × 1.4 × 1.8 cm, which could be interpreted as a tumor lesion or a post-operative scar. The inspection of the hypoplastic breasts was unremarkable for palpable masses, indurations or nipple discharge. The inspection of the axillary lymph nodes was unremarkable for enlarged nodes. The ultrasound of the breast and axilla did not reveal any suspicious lesions. The screening mammography was evaluated as BIRADs II, showing only unsuspicious monomorphic microcalcification on the left breast. Further examination of the patient including vaginal sonography, cervical PAP smear and tumor marker analysis was also unremarkable.

Figure 1.

The amount of transferred breast tissue can be estimated by the location and length of the S-shaped scar resulting from the PMMC flap elevation on the craniolateral area of the right breast. Induration and scar tissue in the region of the right jaw marks the area of breast cancer resection of the inlayed PMMC flap.

The patient was then operated by our oromaxillo facial surgery unit and a tumor measuring 3 × 1.2 × 1 cm3 was excised. The histology this time revealed glandular structures near the pectoral muscle with enlarged ducts showing apocrine metaplasia and ductal hyperplasia as well as a low differentiated adenocarcinoma classified as an invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast with infiltration of the surrounding adipose tissues. The tumor was shown to be positive for estrogen, but negative for progesterone receptors. The HER2neu over expression was defined as +1 on a scale of 0-3 using the DAKO-Hercep® test. The immunohistochemistry showed a diffuse positive reaction for cytokeratin 7 and a negative reaction for cytokeratin 5/6. Due to the positive margins a local reexcision was performed in october 2001. However, the histology of the latter operation did not show any residues of the breast cancer. A sequential radiotherapy could not be performed, since the patient had already been radiated locally to a maximal tolerable dose in 1994.

Furthermore, the patient received 20 mg tamoxifen orally per day as an systemic adjuvant therapy for the receptor positive breast malignancy beginning December 2001 for 6 months. Due to the development of severe side effects as well as endometrium irregularity revealed in a transvaginal sonography (finally clarified as a benign endometrium polyp), tamoxifen was switched to the aromatase inhibitor anastrozol (1 mg orally per day). The patient is under regular follow-ups and to date over 9 years free of any signs of recurrence.

Discussion

The pectoral major myocutaneous flap, as described by Ariyan [6] in the late 70's, is the "working horse" of reconstructive surgery after radical tumor resection of the head and neck region. The large number of publications since then have concentrated mainly on the operation technique, indications and complications that might arise as a result of this flap surgery. In terms of the blood supply, the method seems to be relatively safe with reported complication rates varying between 8.5% to 35%, regarding the high morbidity of these patients. Several modifications of the technique have also been reported. One modification is called the pectoralis major myofascial (PMMF) flap which includes raising the muscle and muscle fascia but without the skin or breast parenchyma. The major advantage of this flap technique is seen in less bulge formation in the jaw region and a better shaping ability [7].

In terms of the blood supply, it also seems to have a higher safety [8,9]. The complication rates of this procedure are largely made up of approximately 8.5% flap necrosis, of which 1.5% are complete necrosis and 18.5% wound healing problems mostly associated with the reported 13.5% orocutaneous fistulas [4]. In subgroups of patients with preexistent chronic medicine disorders, the total complication rate has been reported to as high as 27% compared to patients without any preexisting disorders, showing complication rates of around 8.5%. In the largest published data enclosing 244 patients, the authors report a total complication rate of 35% which include all possible and also minor complications such as hematoma, infection, seroma, dehiscence, fistulas, partial or complete necrosis or other rare complications [10].

However, the theoretic and remote possibility of the development of breast cancer due to transplanted breast parenchyma has so far not been documented. The indication for a PMMC flap is usually seen only in surgery for recurrences or advanced primary carcinomas. Due to the relatively poor prognosis of these patients, the rare and late onset complication of a new primary tumor arising within the flap tissue is usually not of major concern. However, in patients with cured primary cancer the development of a breast carcinoma in such transplants has to be associated with a poor prognosis which mainly results from its difficult diagnosis.

Up to now there is no general consensus for breast cancer screening in patients undergoind PMMC flap; therefore these patients are not routinely screened. According to the literature, only 7 to 22% of all patients undergoing a PMMC flap reconstruction are female [4,11,12]. The average age at time of operation varied between 36 and 59 years. Most patients were operated due to an advanced primary oropharynx carcinoma or a tumor recurrence. The development of such a carcinoma in patients without risk factors as nicotine or alcohol as in our patient is rare and may generally reflect a predisposition towards tumor development. A molecular genetic hallmark of the squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx in female patients without any risk factors is the frequent finding of a p53 mutation and/or positive HPV test. Distinct from this group of patients, there are some patients with genetic germ line mutation of p53, also called the Li Fraumeni syndrome, with a familial predisposition to this type of carcinoma as well as to breast carcinoma.

It seems reasonable to perform mammography and additional breast ultrasound as a preoperative measure in female patients being considered for a PMMC flap. With these routine diagnostic tools it should be possible to gain information on the distribution of breast parenchyma including aberrant breast tissue and thus help to prevent early manifestation or transplantation of preneoplasia or non palpable breast cancer. In this case, the time course from flap surgery to diagnosis of breast cancer was approximately 4 years and therefore any screening at time of transplantation may have been unremarkable. The promotion of breast cancer due to short term recent topical estrogen-therapy because of senile kolpitis seems unlikely but can not be completely excluded. The use of an aromatase inhibitor as an adjuvant systemic endocrine therapy in this hormone receptor positive patient seems to be adequate. It also avoids the additional risk elevation for endometrial carcinoma under tamoxifen. After 9 years the patient is free of any relapses due to the cancer from the oropharynx and the breast. In case of future metastasis, it is pertinent to histologically confirm the origin of the metastatic tissue, before any therapy is initiated or changed.

Part of this work was already published in Oral Oncology EXTRA (2005) 41, 238-241

References

- Gamatsi IE, McCulloch TA, Bailie FB, Srinivasan JR. Malignant melanoma in a skin graft: burn scar neoplasm or a transferred melanoma? Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:342. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2000.3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin SA, Love SM, Goldwyn RM. Recurrent breast cancer following immediate reconstruction with myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:1191. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199405000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold PG, Pairolero PC. Use of pectoralis major muscle flaps to repair defects of anterior chest wall. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:205. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek S, Lawson W, Biller HF. An analysis of 133 pectoralis major myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:460. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denewer AT. Myomammary flap of pectoralis major muscle for breast reconstruction: new technique. World J Surg. 1997;21:57. doi: 10.1007/s002689900193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyan S. The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. A versatile flap for reconstruction in the head and neck. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:73. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197901000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbar RIS, Funk GF, McCulloch TM, Graham SM, Hoffmann HT. Pectoralis major myofascial flap: a valuable tool in contemporary head and neck reconstruction. Head and Neck. 1997;19:412. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199708)19:5<412::AID-HED8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righi PD, Weisberger EC, Slakes SR, Wilson JL, Kesler KA, Yaw PB. The pectoralis major myofascial flap: clinical applications in head and neck reconstruction. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:96. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, okamoto K, Nakanishi Y, Nakano H, Iwagami Y, Morita N. Myofascial flap without skin for intra-oral reconstruction. 2: Clinical studies. Int J Clin Oncol. 2001;6:143. doi: 10.1007/PL00012097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Gullane P, Brown D, Irish J. Pectoralis major myocutaneous pedicled flap in head and neck reconstruction: a retrospective review of indications and results in 244 consecutive cases at the Toronto General Hospital. J Otolaryngol. 2001;30:34. doi: 10.2310/7070.2001.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli ML, Pecorari G, Succo G, Bena A, Andreis, Sartoris A. Pectoralis major myocutaneous flap: analysis of complications in difficult patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:542. doi: 10.1007/s004050100389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JS, JSP, Yiacoumettis AM, O'Neill T. Some observations on 112 pectoralis major myocutaneous flaps. Am J surg. 1984;147:273. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]